Introduction

The phenomenon of the reuse of artefacts has a long history, including manifold behavioural patterns in past communities. Reuse processes are defined by Schiffer (Reference Schiffer2010: 32) as changes occurring in both the usage and the user of an artefact. Studies from around the world have demonstrated multiple ways in which artefacts were reused (e.g. Gillett Reference Gillett and Johnson2012; Delfino Reference Delfino2014; Amick Reference Amick2015; Raczek et al. Reference Raczek, Sugandhi, Shirvalkar, Pandey, Frenez, Jamison, Law, Vidale and Meadow2018; Ota et al. Reference Ota, Srivastava and Pandey2020). In the South Asian context, while the reuse of artefacts is widespread and ongoing, few studies have specifically focused on the reuse of artefacts as related to pre- and protohistory. Focus has instead been on reuse in historical contexts or as incidental to larger studies (Patel Reference Patel2009).

This study aims to address issues relating to reuse in prehistory, specifically the reuse of ringstones. In the Indian context, a ‘ringstone’ is a tool defined by its morphological and purported functional attributes; different terminologies exist for particular cultural phases ranging from the Upper Palaeolithic (Raju Reference Raju, Mishra and Bellwood1985) to historical periods (Allchin Reference Allchin1995). Here, I follow Sankalia's (Reference Sankalia1964: 85) definition: thick, small, round or rectangular stones with a central hole and surfaces smoothed by pecking and grinding. The range of potential functions for these artefacts (as weights in digging sticks, mace-heads and so on) remains sparsely studied in India.

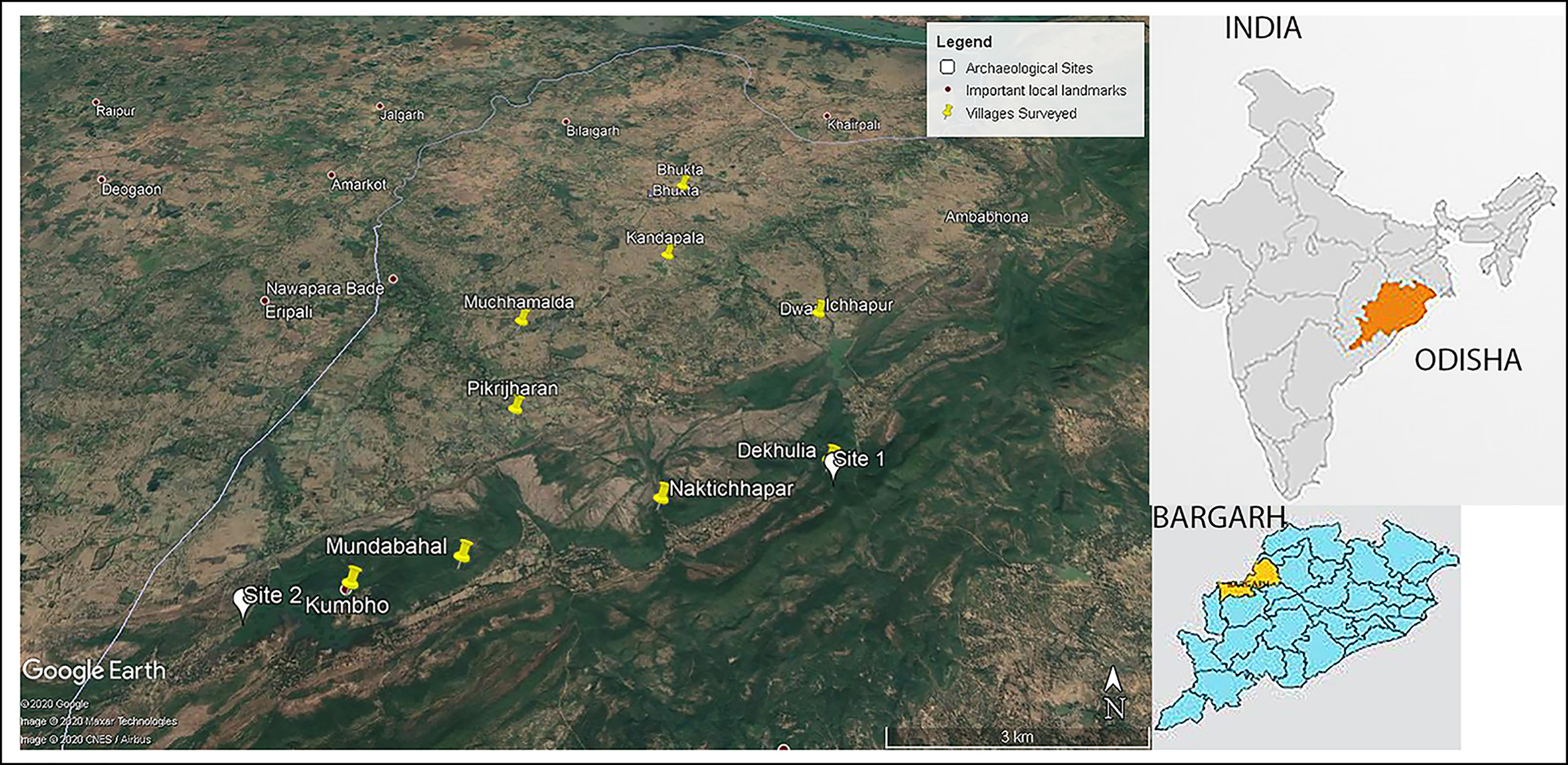

This article considers the reuse of ringstones in the Bargarh district, Odisha, Eastern India (Figure 1). Field investigations were carried out in the upland plains in the north-eastern region, where ringstones were observed to be reused within contemporary communities specifically in connection with cattle and associated medicinal purposes (Bhattacharya Reference Bhattacharya2019).

Figure 1. Location of the study region Bargarh, India, showing the villages studied and neighbouring archaeological sites in the region (Google Earth Pro, 15 January 2020, 21°34′48.45″ north, 83°24′16.69″ east, Maxar Technologies).

Reuse of ringstones

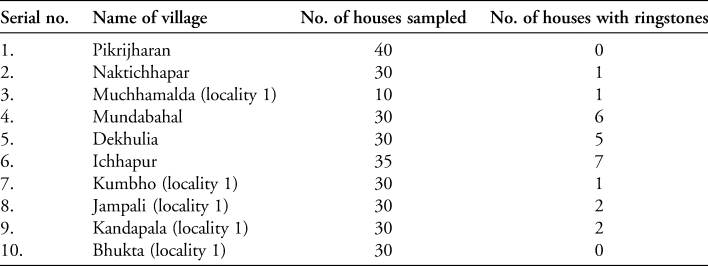

Surveys were conducted on households from ten villages (n = 295 households out of approximately 475; figures from Census of India 2011 (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner 2019); Table 1). Of the ten villages, eight had evidence for the reuse of ringstones (25 ringstones in total), with the remaining two villages not practising reuse, but aware of its perceived value. Interviews were conducted in instances where ringstone reuse was discovered. The respondents were all men, as designated ‘heads of the household’. The villages were primarily agro-pastoral comprising Binjhals, Bhuyan, Nishad and Yadav communities (Census of India 2011, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner 2019).

Table 1. Villages and houses sampled for this study recording details of the ringstones studied.

The reuse of ringstones in the Bargarh region is based on a myth that, during the monsoon, ‘flying snakes’ (Chrysopelea sp.) may cast their shadow on cattle, leading them to fall ill with fits. Afflicted animals are brought indoors and the ringstone or ‘Parkipadhor’ is tied around the neck for seven days; this being the sole treatment administered (Figure 2). In some instances, these beliefs are transferred to goats, with smaller or broken ringstones being used. The ringstones are not associated with any spiritual powers, but are used as a physical remedy, tested and proven by ancestral use. The community believes that they know the exact cause of the disease, its recovery period and the efficacy of the ringstone treatment. The origin of the tradition is uncertain; it appears to be handed down as a family tradition.

Figure 2. An example of ringstone reuse; the ringstone is tied around the neck of a sick cow (photograph by S. Bhattacharya).

Most ringstones were reportedly recovered from forests adjoining villages at distances of around 5km, probably collected while grazing cattle or goats. There is no correlation between ringstone counts and cattle wealth or family size in the study region. Nor do they have any economic or prestige value; the artefacts are loaned and borrowed without any sort of exchange, monetary or otherwise. It is important to note that local communities believe that ringstones are naturally occurring objects and lacking any cultural affinities. Despite this, their unique morphology may have influenced their choice as objects with healing properties.

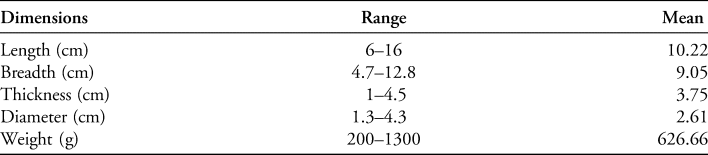

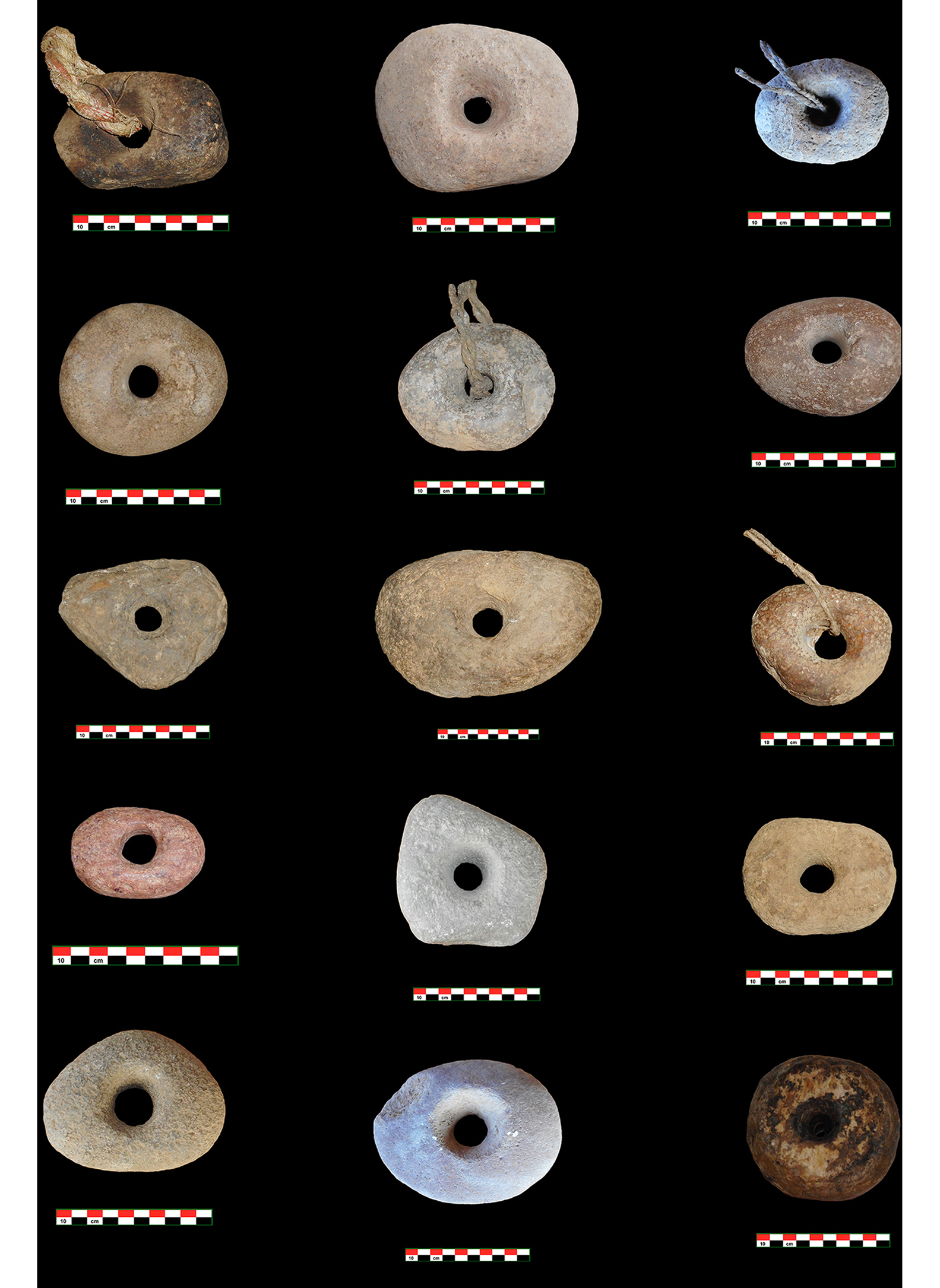

Ringstones recorded in the study (complete, n = 18; broken, n = 7) were primarily made from charnockite, which was potentially sourced locally (Table 2). Shapes were oval, circular, oblong, flat, elliptical and square (Figures 3–4). Some were weathered and abraded owing to either natural weathering processes prior to collection or subsequent modes of storage (left outdoors exposed to the elements).

Table 2. Measurements of complete ringstones from the study area.

Figure 3. Complete ringstones from the study area (scales in centimetres; photographs by S. Bhattacharya).

Figure 4. Broken ringstones from the study area (scales in centimetres; photographs by S. Bhattacharya).

Two archaeological surface sites (Dekhulia and Kumbho) with blade- and flake-based assemblages, whose chronology is as yet unclear, were noted in areas coinciding with the find-spots of the ringstones. Prehistoric sites reported in the region appear to be microlithic (Deep Reference Deep2018), with the nearest reported Neolithic sites being at ranges of 60–80km from the villages in the study area (Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Ota, Nimje, Yadav and Dogra1990–1991: 40; Behera Reference Behera2013; Padhan Reference Padhan2018).

Discussion

The reuse of older artefacts in archaeological records is largely related to resource procurement (Amick Reference Amick2015). In the Indian context, evidence comes from Budihal where ashmounds (accumulations of vitrified ash in the context of parts of the South Indian Neolithic) were reused by later Neolithic populations and subsequently by historical communities (Paddayya Reference Paddayya2019). This is also noted in the case of reuse of Neolithic celts (stone tools) in Tamil Nadu (Selvakumar Reference Selvakumar2008) and in Bengal (Chattopadhyay et al. Reference Chattopadhyay, Bose, Acharya, Bandyopadhyay and Dikshit2013). In Odisha, ringstones are reused in the Mayurbhanj for religio-medicinal purposes (Mohanta Reference Mohanta2013). In all these cases, the resources from an archaeological setting are readily available and thus are reused to meet different needs. A study from Rajasthan (Raczek et al. Reference Raczek, Sugandhi, Shirvalkar, Pandey, Frenez, Jamison, Law, Vidale and Meadow2018) showed how the residents of a village recycle modern and ancient items in the same way, in part because they do not fully understand the antiquity and archaeological significance of the artefacts.

The case from Bargarh is not very different. Communities collected ringstones from archaeological sites attributing them natural origins and, not recognising their cultural heritage, utilised them in particular ways. The villages firmly believe they are collecting natural stones; in their view they are not progressively disturbing archaeological sites, but continuing ancestral practices passed down the generations through oral traditions. At present the archaeological context of the ringstones is unclear and remains a subject for future studies. In the Indian context, such studies have the potential to explore concepts of the modern reuse of archaeological artefacts, of changing behaviour through time and to contribute to the assessment of patterns of site-disturbance through these practices.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of my MA dissertation at the Pandit D.D.U Institute of Archaeology. I thank V.N. Prabhakar, director of the institute for permitting me to conduct the study, and Shanti Pappu, my guide. I thank Ramesh Bhuyan and Jagdeesh Naik for their help in the fieldwork, K.K. Basa for his insights into Odisha archaeology, Kumar Akhilesh for his valuable suggestions while drafting the article, and Paromita Bose, Prachi Joshi, Sharodiya Bhattacharya and Ritabrata Dobe for helping with the maps, data presentation, and the economic and geological insights, respectively.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.