Introduction

The modern village of Hawwariya is located on the southern shore of Lake Mareotis in northern Egypt and is about 40km south-west of Alexandria and 17km north of the Christian sanctuary of Abū Mīnā. Various scholars have identified the site with ancient Marea or Philoxenite (Rodziewicz Reference Rodziewicz, Blue and Khalil2010; Derda Reference Derda, Myśliwiec and Ryś2020). Since the late 1970s, Egyptian, American, French and Polish archaeologists have been conducting archaeological excavations at this site. These investigations have focused primarily on uncovering individual Byzantine buildings (baths, churches, houses, workshops, a mill) and reconstructing their floorplans and the way that they functioned. This approach, however, failed to capture the wider urban and historical context of the functioning of the town. The form of the town grid, and the way in which various parts of it came into being, has been neglected in research to date, despite this holding unique information about the construction of large settlements in late antiquity. To maximise the potential of this site, the University of Warsaw has been conducting a non-invasive survey of the entire site, combined with archaeological probing in selected areas, since 2017.

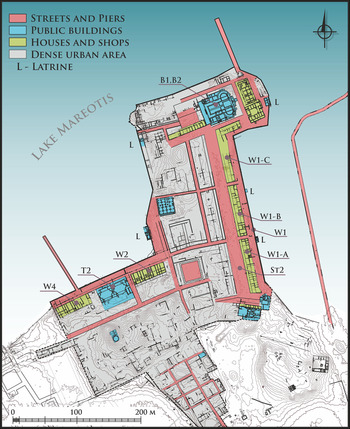

This research has made it possible to identify magnetic anomalies indicating the extent of a dense urban area without defensive walls (Derda et al. Reference Derda, Gwiazda, Misiewicz and MaŁkowski2021). These activities were accompanied by topographical survey and making plans of architectural surface remains. The map this produced made it possible to identify an ordered development covering 13ha (Figure 1). Its main elements were a complex system of straight streets with adjoining buildings serving various functions and an artificial waterfront linked to an extensive port infrastructure.

Figure 1. Map of the Byzantine urban development area in Marea (map by A.B. Kutiak & W. Małkowski, with modifications by M. Gwiazda; courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

Results

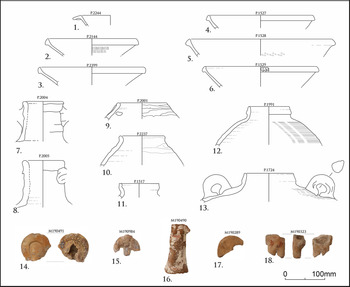

The excavations in the eastern part of the site established that, with the construction of the waterfront located in area W1 (Figure 1), large quantities of soil were deposited on the western side of the built structure, in some cases containing waste associated with the production of lime or gypsum (Figure 2). This was deposited here to raise and level the ground for the next phase of the construction—the row of buildings W1-A, B, C and adjacent street (St2) (Figure 1). Ceramic vessels and terracotta figurines recovered from these levelling layers indicate that all these structures were erected no earlier than the second half of the sixth century AD (Figure 3). Built at the same time was the monumental 18m-wide main urban street (St2) running north–south from the Great Basilica (B1) to the southern baths.

Figure 2. Levelling layers under buildings W1-B, W1-A and St2. The white dotted line marks the top of the levelling layers (photographs by M. Gwiazda, courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

Figure 3. Fineware vessels, amphorae and terracotta figurines from the levelling layers: 1) African Red Slip Ware; 2–6) Late Roman D Ware; 7–8) Late Roman amphorae 1; 9–10) Late Roman amphorae 4; 11–13) Egyptian amphorae 5/6; 14–18) anthropomorphic and zoomorphic terracotta figurines from Abū Mīnā (drawings by K. Danys; digitlisation by M. Gwiazda; photographs by T. Derda; courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

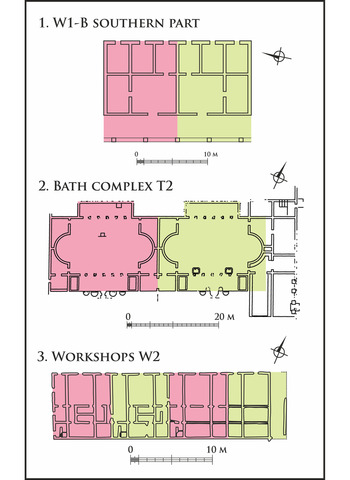

Analysis of the plans of buildings W1-A, B and C indicated that they consisted of modules with repeated plans and fixed sizes (14 × 10m) (Figure 4.1). Each had a row of three shops opening to the east towards the lake waterfront. Behind these were two additional rooms for habitation and, to the rear of those, a portico adjacent to street St2. The adjoining modules were not connected by passageways, indicating that each was a self-contained unit used independently of the others. At the same time, all the modules within each building formed a structural whole that made up a uniform straight frontage 260m in length.

Figure 4. Modular buildings in Marea (drawings by M. Gwiazda & A.B. Kutiak; courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

Other examples of buildings constructed using modular plans are known from Marea. On the western waterfront was a biapsidal bath building (T2), consisting of two frigidaria (cold pool rooms) with identical floorplans (Figure 4.2). These were flanked on the east and west sides by two buildings interpreted as houses with workshops (Figure 1: W2 & W4). Each consisted of four modules of uniform size and layout (Figure 4.3). This widespread use of duplicate floorplans leaves no doubt as to the nature of these foundations. They were certainly not individual building projects, but buildings constructed as part of a larger urban programme that covered an extensive part of the town.

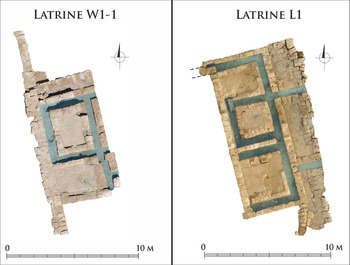

Another element of the same building programme was an artificial waterfront stretching along the entire shoreline adjacent to the dense urban development. This construction consisted of rows of limestone blocks joined by hydraulic mortar. In addition to the streets running along the waterfront, it also included at least five public latrines erected at the same time (Figure 1: L). These were characterised by a repetitive plan, consisting of two to three platforms surrounded by sewage channels discharging waste directly into the lake (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Latrines L1 and W1-1 connected to the artificial waterfront. The location of the sewers is marked in blue (photographs by M. Gwiazda; courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

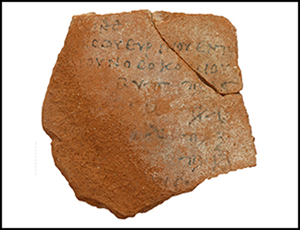

Very important information about the functioning of this settlement is also provided by a set of ostraca (pottery with writing inked on the surface) documenting a workshop engaged in repair activities at the turn of the sixth and seventh century AD (Figure 6). They attest to, among other things, the presence of a nosokomeion, or hospital, a building that became common in the Byzantine period. The presence of such a building, together with the two bath complexes and the latrines, indicates the care taken by the town's planners over the health of the residents.

Figure 6. Photograph of an ostracon mentioning the renovation of the nosokomeion (hospital) (photographs by T. Derda; courtesy of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw).

Another argument pointing to the implementation of a large-scale development programme can be found in the southern part of the site. Here rectangular building plots are marked out by streets intersecting at right angles (Figure 1), which is a rather uncommon arrangement in Byzantine town plans.

To date, limited traces of an older settlement have been identified only at the northern end of the site. The oldest of these are associated with a workshop producing wine amphorae, which operated here in the second to third centuries AD. In the immediate vicinity is a 120m-long pier, possibly also dating from Roman times, which was used until the town's abandonment. On the site of the amphorae workshop, a small church (B2) with a baptistery was built around the fifth century AD (Babraj et al. Reference Babraj, Drzymuchowska, Tarara, Myśliwiec and Ryś2020; Derda Reference Derda, Myśliwiec and Ryś2020). This building was demolished to floor level in the sixth century AD, and one of the largest Christian basilicas in Egypt was erected in its place (Figure 1: B1).

Discussion

The evidence presented here indicates that Marea was a well-planned town that took the basic needs of the civilian population into account, and the larger part of it was built within an urban planning project. It preserves the prevailing ideals of the time in its plan, with the presence of a large church adjacent to the most important street.

Few new, large-scale, urban undertakings at the end of antiquity are known. Individual examples come from the border areas of the Byzantine Empire, exemplified by Justiniana Prima (modern Serbia), or Zenobia and Resafa (modern Syria) (cf. Rizos Reference Rizos2017). Of all of these, only the settlement from northern Hawwariya lacked defensive walls, which is clearly distinctive and suggests a different type of settlement. It should also be emphasised that the construction of a significant part of this site occurred in the second half of the sixth century AD. This indicates that it was the latest monumental Byzantine urban project before the Arab conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean in the second quarter of the seventh century AD.

Funding statement

The Polish National Science Centre (grant 2017/25/B/HS3/01841) financed this project.