Late Neolithic Orkney

Orkney is rightly famed for the exceptional quality and preservation of its Neolithic archaeology. House walls can stand above head-height, and chambers in tombs display outstanding masonry skill. The diversity of evidence is also striking, from settlements to chambered tombs, to stone circles and their quarries. There is varied material culture, especially in the Late Neolithic, with the presence of Grooved Ware pottery and a wide array of stone objects, including stone balls and maceheads. New discoveries continue, not only on small, outlying islands neglected in previous research, such as the settlement of Braes of Ha'Breck, on Wyre (Thomas & Lee Reference Thomas and Lee2012), but also in well-explored areas, such as the settlement complexes of Barnhouse, the Ness of Brodgar and Bookan on western Mainland (Richards Reference Richards2005; Card et al. Reference Card, Mainland, Timpany, Batt, Bronk Ramsey, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Marshall and Whittle2017; Christopher Gee pers. comm.). The Ness of Brodgar has further enriched the archaeological record with its abundance of impressive buildings, wealth of interior fittings and incised and painted decoration (Card & Thomas Reference Card, Thomas, Cochrane and Jones2012). Thus, the ‘Heart of Neolithic Orkney’ was granted World Heritage status in 1999 for very good reasons (Downes et al. Reference Downes, Gibson, Gibbon and Mitchell2013).

The stone houses, grouped in settlements, and the monuments, which together define the Orcadian Neolithic, also provide opportunities to follow trajectories of change at the local, and even household, level of social interaction. Previous research charted the gradual development of a process of settlement nucleation beginning with small-scale dispersed settlements, with round-based pottery, in the mid fourth millennium cal BC. By the later fourth and into the third millennium cal BC, larger conglomerated settlements with Grooved Ware appear; towards the end of the Neolithic sequence, there are juxtaposed larger houses, later Grooved Ware and, in some cases, Beaker pottery (Richards & R. Jones Reference Richards and Jones2016). Chambered tombs reached their peak of architectural sophistication and spatial complexity with Maeshowe passage graves (Davidson & Henshall Reference Davidson and Henshall1989). Stone circles in the form of the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar appear to be innovations of the earlier and mid third millennium cal BC (Richards Reference Richards2013).

Grooved Ware pottery emerged in the Late Neolithic, its flat-based forms supplanting a round-based repertoire (Cleal & MacSween Reference Cleal and MacSween1999). One interpretation of the trajectory of social change was that the Late Neolithic saw the development of chiefdoms, following earlier segmentary societies (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1979). Other accounts have stressed the complexity and diversity of the evidence, and have posited different models of social change at other scales with, among other features, an emphasis on community and great houses (Sharples Reference Sharples1985; Richards Reference Richards2005, Reference Richards2013; Richards & R. Jones Reference Richards and Jones2016).

Through all this run fundamental questions of chronology, especially timings, durations and tempo: for how long were the Neolithic settlements inhabited and was this settlement continuous? Can we date the different stages of settlement conglomeration through the Neolithic? Is there any consistency or concurrence in this process between settlements? Did the monumentality exemplified by Barnhouse and the Ness of Brodgar co-exist? When did Grooved Ware pottery emerge, and did its adoption coincide with the ending of previous bowl traditions? How quickly did it develop and change? When were Maeshowe passage graves built, and how do they relate to the temporal trajectory of stalled chambered cairns? When were the Orkney stone circles erected? Was the initiation of all these changes simultaneous, and what was the tempo of change throughout this period? Before we can address such questions concerning the nature of social formations and the appearance of monuments in Late Neolithic Orkney, we need to consider, critically, the nature of dwelling, as represented by settlement histories, and that provides the focus of this article. The quantity and range of evidence now available offer the possibility of unravelling a more complicated sequence, specific site histories and the changing social circumstances that they exemplify.

Scientific dating and Bayesian chronological modelling on Orkney

When Colin Renfrew started excavation of the chambered cairn at Quanterness in 1972, there were no radiocarbon dates for Orkney Neolithic sites (Renfrew et al. Reference Renfrew, Harkness and Switsur1976: 194). This situation quickly changed: by the mid 1980s, over 80 radiocarbon measurements relating to Neolithic activity on 11 sites across the islands could be listed and interpreted on a calibrated calendar timescale (Clark Reference Clark1975; Renfrew & Buteux Reference Renfrew, Buteux and Renfrew1985).

Although only small numbers of additional radiocarbon dates were obtained over the following 15 years, by 2000 Patrick Ashmore was able to muster a total of 119 radiocarbon dates from 18 sites in his synthesis of the chronology of Neolithic Orkney (Ashmore 2000). This study relied on the visual inspection of calibrated radiocarbon dates and summed probability distributions of groups of related calibrated dates from phases of activity at particular sites. The limitations of both approaches for inferring accurate chronologies of past activity have since become appreciated (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Bronk Ramsey, van der Plicht and Whittle2007), although Ashmore's (Reference Ashmore1999) requirement for radiocarbon results on short-lived, single-entity samples and his emphasis on a critical assessment of the archaeological provenance of the dated material have substantially improved the utility of the dates obtained over the succeeding decades.

The 14 radiocarbon dates from the phase I and II settlements (trench 1) at Skara Brae (Renfrew & Buteux Reference Renfrew, Buteux and Renfrew1985) formed the basis of one of the first case studies for the application of a Bayesian approach to interpreting chronology in archaeology (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Kenworthy, Litton and Smith1991). This approach combines calibrated radiocarbon dates, or other forms of scientific dating, with knowledge of the archaeological contexts from which they are derived, to produce a series of formal, probabilistic date estimates. Stringent demands are made of both the radiocarbon dates and our archaeological understanding of stratigraphy, associations, sample taphonomy and context in general. Thus, the combined chronology should be both more reliable and more precise than its individual components, as it is reliant on multiple strands of reinforcing evidence (Bayliss & Whittle Reference Bayliss, Whittle, Wylie and Chapman2015).

Bayesian chronological modelling was not widely adopted for the Orcadian Neolithic at this time due to a perception that Bayesian analysis could only provide refined chronologies where there was a deep sequence of direct stratigraphic relationships (Ashmore Reference Ashmore, Simpson and Gibson1998: 142–45). Furthermore, in considering the chronology of Grooved Ware in Scotland, Ashmore (Reference Ashmore, Simpson and Gibson1998: 142) asserted that there was limited potential for refining the dating of its first occurrence, as the shape of the radiocarbon calibration curve means that results on short-lived samples actually dating to between 3300 BC and 3100 BC would calibrate to “somewhere in the period 3400–3000 (or even 2900) cal BC”.

Technical developments in both radiocarbon dating and the statistical modelling of dates over recent decades can now be used to challenge this view. Not only have the quoted errors on radiocarbon measurements approximately halved since Ashmore's work (Reference Ashmore, Simpson and Gibson1998), but it has now become possible to date calcined bone (Lanting et al. Reference Lanting, Aerts-Bijma and van der Plicht2001). The potential for Bayesian statistics to provide refined chronologies on a routine basis, even in situations where stratigraphic sequences are limited, has also become clearly apparent (Bayliss Reference Bayliss2009). This increased precision means that what previously was an undifferentiated plateau in the calibration curve for the late fourth millennium cal BC now resolves into a series of micro-wiggles that can be employed as the basis for much more constrained chronologies (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

The potential of these techniques to refine narratives for Neolithic Orkney is now being exploited. Major programmes of new dating and analysis have, for example, been undertaken on the stalled cairn at the Holm of Papa Westray North and the chambered cairn at Quanterness (Ritchie Reference Ritchie2009: 59–66; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010). Recent research has also seen chronological modelling of Grooved Ware settlement sites at Pool, Sanday, Barnhouse and Skara Brae, Mainland, and preliminary models for the Ness of Brodgar, Mainland and the Links of Noltland, Westray, where excavation is continuing (MacSween et al. Reference MacSween, Hunter, Sheridan, Bond, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2015; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016a; Card et al. Reference Card, Mainland, Timpany, Batt, Bronk Ramsey, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Marshall and Whittle2017; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Sharples, Shepherd, Sheridan, Armour-Chelu, Bronk Ramsey, Dunbar, Reimer, Marshall and Whittlein press; Clarke & Shepherd forthcoming). Further radiocarbon dates have also been obtained on samples of Orkney vole (Microtus arvalis) from a range of Neolithic sites (Martínková et al. Reference Martinková, Barnett, Cucchi, Struchen, Pascal, Fischer, Higham, Brace, Ho, Quere, O'Higgins, Excoffier, Heckel, Hoelzel, Dobney and Searle2013).

This article is based on a review of 613 radiocarbon measurements and 79 luminescence ages from 31 sites (Figure 1; Table 1). This analysis builds upon the work of Griffiths (Reference Griffiths, Richards and Jones2016), who provides a synthesis of the chronology of activity in the fourth millennium cal BC. The original intention was to confine our analysis to Late Neolithic activity associated with Grooved Ware, but it soon became apparent that round-based pottery (as found at the Isbister chambered tomb) and Grooved Ware (as found at Barnhouse) were almost certainly in contemporaneous use during the thirty-first century cal BC, at the very least (Figure S1 in online supplementary material (OSM); Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016a: figs 6–8). We therefore consider all the dating evidence associated with Grooved Ware sites and with sites of the later fourth millennium, although our analysis centres on the centuries between c. 3300 and 2300 cal BC.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of sites considered in this article.

Table 1. Summary of scientific dating evidence considered in this article.

All the chronological modelling discussed here was undertaken using the OxCal v4.2 program (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the atmospheric calibration curve for the northern hemisphere published by Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). The chronological models for each site are described in the OSM, and are defined exactly by the brackets and OxCal CQL2 keywords on the left-hand side of the technical graphs (http://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/). The posterior density estimates output by the model are shown in black, with the unconstrained calibrated radiocarbon dates shown in outline. The other distributions correspond to aspects of the model. For example, start_isbister_primary is the estimated date when burial in the chambered tomb at Isbister began (Figure S1). In the text and tables, the Highest Posterior Density intervals of the posterior density estimates produced by the models are given in italics, followed by a reference to the relevant parameter name and the figures in which the model that produced it is defined. Key parameters for the chronology of Late Neolithic Orkney are listed in Tables S4 and S5.

The Late Neolithic timescape of Orkney

Formal modelling not only enables more precise chronologies for individual sites, but also allows us to characterise the timing and duration of different types of phenomena, and then to combine these into a much more differentiated narrative than previously available. First, we set out some of what we consider to be key elements in the Late Neolithic narrative (referring the reader to the OSM for site details).

Chambered cairns

Figure 2 shows models for the use of stalled cairns and Maeshowe passage graves in Orkney. Sites with more than two radiocarbon dates are represented by the estimated dates for the start and end of activity taken from the site-based model. We have taken the radiocarbon dates on human remains from within the primary chamber deposits to indicate the period when the tombs were used for burial. Although it is possible that these may represent secondary burials, the number of dated individuals across the period of burial at, for example, Quanterness (Figure S6), suggests that this is unlikely. The single date from the Knowe of Lairo (SUERC-45833) is not included in either model, as this tomb underwent a series of modifications and it is not clear from which phase of activity the dated sample derives. We have interpreted the dated human remains at the Point of Cott to relate to the use of the stalled cairn (Figure S16).

Figure 2. Probability distributions of dates from chambered cairns in Orkney. Each distribution represents the relative probability that an event occurred at a particular time. Two distributions have been plotted for each of the dates: one in outline, which is the result of simple radiocarbon calibration, and a solid one based on the chronological model used. Distributions other than those relating to particular samples have been taken from models defined in Figures S1 (Isbister), S3 (Cuween), S6 (Quanterness), S13 (Knowe of Rowiegar), S16 (Point of Cott) and S18 (Holm of Papa Westray North), and MacSween et al. (Reference MacSween, Hunter, Sheridan, Bond, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2015: fig. 13) (Quoyness). Other distributions are based on the chronological model defined here, and are shown in black. For example, the distribution ‘start stalled cairns’ is the estimated date when human burial began in these cairns. The large square brackets down the left-hand side of the figure, along with the OxCal keywords, define the model exactly.

It is clear that both stalled cairns and Maeshowe passage graves (Figure 3g–h) were first constructed in the middle centuries of the fourth millennium cal BC, although with current evidence, it is not possible to say which came first. Human remains may have been deposited in Maeshowe passage graves into the middle centuries of the third millennium, whereas the primary deposition of human remains in stalled cairns appears to have ended in the first quarter of the millennium. Although a number of dated tombs became horned cairns in later phases, only two dates associated with this type of monument are available (Table 2). These suggest that the example at Vestra Fiold, at least, was constructed in the second quarter of the third millennium cal BC (Figure 2).

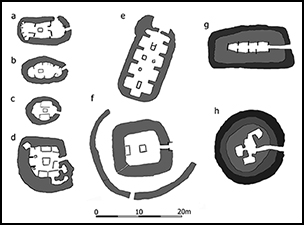

Figure 3. Architectural range of Neolithic stone house structures: a) Knap of Howar; b) Stonehall Knoll house 3; c) Barnhouse house 6; d) Skara Brae hut 1; e) Ness of Brodgar structure 8; f) Barnhouse structure 8; and chambered cairns: g) Knowe of Yarso stalled cairn; h) Wideford Hill passage grave.

Table 2. Radiocarbon measurements and associated stable isotopic values from Vestra Fiold, Mainland.

In particular chambered cairns, the deposition of animal remains occurred after that of human remains, although deposition sometimes overlapped. A model for the currency of this activity is also shown in Figure 2. Animal remains were clearly deposited in some tombs, while human remains were deposited in others.

The Orkney vole

The common vole (Microtus arvalis) is significant to the discussion of Neolithic Orkney, as it is found today on Orkney and on the European continent, but not in mainland Britain. As the species cannot have survived the Last Glacial Maximum on the archipelago, it was probably introduced via direct long-distance sea travel between Orkney and the continent.

Recent studies of dental morphology and mitochondrial DNA have been undertaken to identify the probable origins of the Orkney vole population (Martínková et al. Reference Martinková, Barnett, Cucchi, Struchen, Pascal, Fischer, Higham, Brace, Ho, Quere, O'Higgins, Excoffier, Heckel, Hoelzel, Dobney and Searle2013; but see Sheridan & Pétrequin Reference Sheridan, Pétrequin, Whittle and Bickle2014 for a critique). This work has been supplemented by a programme of direct AMS radiocarbon dating of vole remains from Neolithic sites in Orkney. Two existing measurements from the Links of Noltland (OxA-1081–1; Table S3) were performed in the early years of AMS dating, and fall outside the span of the measurements undertaken more recently (Figure 4). Given the significant refinements in bone pre-treatment protocols for radiocarbon dating that have occurred in the intervening period (e.g. Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1988), we chose to exclude these measurements from the model shown in Figure 4. This model suggests that the common vole first appeared in Orkney in 3455–3100 cal BC (95% probability; start Orkney voles; Figure 4), probably in 3315–3135 cal BC (68% probability).

Figure 4. Probability distributions of dates from specimens of Orkney vole from Neolithic sites. The format is identical to that of Figure S1. Measurements followed by a question mark and shown in outline have been excluded from the model for reasons explained in the text, and are simple calibrated dates (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993). The large square brackets down the left-hand side of the figure, along with the OxCal keywords, define the model exactly.

Late Neolithic settlement

Figure 5 summarises the estimated dates for the occurrence of different activities in later fourth- and third-millennium Orkney. The horizontal bars represent the probability that a particular site or monument-type was in use in a particular 25-year period (light shading is less probable, darker shading more probable). For the settlements and stone circles, distributions have been taken from the site-based models defined or referenced in the OSM. Distributions for the chambered cairns derive from the model shown in Figure 2, and those for the appearance of the Orkney vole from the model defined in Figure 4.

Figure 5. Schematic diagram showing the periods of use of dated Neolithic settlements in Orkney in the later fourth and third millennia cal BC (mauve: associated with round-based pottery; green: associated with flat-based pottery; the site of Green is left black as the ceramic association of this unpublished site is uncertain). The periods of human burial in stalled cairns and passage graves are also shown, along with the period when animal remains were deposited within them. The dates of construction for the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, and the date of the appearance of Orkney vole, are also shown.

House architecture

Figure 6 summarises the model for the currency of timber and stone houses on Orkney (Figures S19–24). The first houses were timber (57.3% probable), in use from 3560–3360 cal BC (95% probability; start_timber_houses; Figure 6), probably from 3445–3370 cal BC (68% probability). The first stone houses were linear in form (63.1% probable), being in use from 3490–3300 cal BC (95% probability; start_linear; Figure 6), probably from 3410–3330 cal BC (68% probability). Timber and stone houses were, therefore, both concurrently in use during the second half of the fourth millennium cal BC.

Figure 6. Probability distributions for the beginnings and endings of the use of Neolithic timber and stone houses in Orkney. The format is identical to that of Figure S1, although the tails on some distributions have been shortened. The distributions are derived from the model shown in Figures S19–24.

Settlement intensity

Figure 7 provides an estimate for the intensity of settlement activity in ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ areas across Orkney from 3500–2200 cal BC, derived from estimates of the number of structures in use on individual sites in 25-year periods (see Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016a: fig. 14). The intensity of activity in the core (defined as the concentration of sites and monuments in the Stenness-Brodgar area) from c. 3125–2850 cal BC (Figure 7) occurs in tandem with the start of a general decline in the periphery (simply defined as the rest of the archipelago), with a clear lull in settlement intensity apparent in the twenty-eighth century cal BC. Although settlement in the periphery appears to recover to its early intensity levels during the mid third millennium BC, the core shows no similar recovery; peripheral settlement intensity goes into a second major decline in the later part of the third millennium cal BC.

Figure 7. The number of dated Neolithic houses in use in Orkney during the later fourth and third millennia cal BC. The ‘core’ area contains the settlements at Barnhouse and the Ness of Brodgar, the ‘periphery’ contains all other settlements.

Discussion

The emergent chronology set out above and in the OSM appears to present a more complex picture of extensive and overlapping activities, concurrences and discontinuities occurring at different sites throughout Orkney during the fourth and third millennia cal BC. This prompts a radical reassessment of this period.

First, there is now broader evidence to support the contemporaneity of early stalled chambered cairns and timber houses (Richards & A. Jones Reference Richards, Jones, Richards and Jones2016). The linear stone houses divided by upright stone slabs that were previously considered to characterise the Early Neolithic (e.g. the Knap of Howar) are now revealed to be a later development c. 3300 cal BC (Figures 3a–b & 6). Round-based pottery was in use within the early timber settlements. From this point onwards, a very complex picture is revealed of round-based bowls and Grooved Ware vessels overlapping in use between various forms of house architecture at different sites across the archipelago, particularly during the thirty-second to thirtieth centuries cal BC (Figure 3a–f). Stalled cairns and Maeshowe passage graves (Figure 3g–h) seem to have been initially employed as places for human burial, and later as places where animal remains were deposited. This later phase of activity may coincide with the addition of horn-works to some stalled cairns to create large long mounds or, in the case of Vestra Fiold, an entirely new mound (Richards Reference Richards2013: 152–76). On the basis of dating of human bone from Quanterness, it can be argued that passage grave architecture began in Orkney around 3400 cal BC. On current evidence, this would make Orcadian passage graves among the earliest examples of this architecture in Britain and Ireland, accepting that Carrowmore is of an entirely different architectural form (contra Hensey Reference Hensey2015).

Secondly, we are now able to trace in some detail the development of fourth-millennium cal BC settlement and identify the tendency towards nucleation. This trend continued into the third millennium cal BC, culminating at sites such as Skara Brae, which has substantial conjoined stone-houses and encircling casing walls containing thick ‘midden’ material (Shepherd Reference Shepherd, Hunter and Sheridan2016). Between 3200 and 3000 cal BC, two main occurrences transform the appearance of the settlements into large mounds: superimposed or recurrent nucleated houses, and the deposition of substantial midden material.

This phenomenon occurs throughout Orkney at sites as distant as Stonehall, Mainland, and Pool, Sanday (Hunter Reference Hunter2007; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Challands, Jeffrey, Jones, Jones, Muir, Richards and Jones2016b). With more detailed chronological analysis, settlement histories provide a more punctuated narrative of dwelling. The complex sequence at Pool reveals discrete superimposed phases of occupation respectively associated with early and late forms of house architecture and Grooved Ware (MacSween et al. Reference MacSween, Hunter, Sheridan, Bond, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2015). A similar, but undated, division is observable in the nearby settlement at the Bay of Stove, Sanday. Here, a nucleated Neolithic settlement is eroding from a small cliff, and a massive Neolithic settlement mound lies approximately 200m inland. Incised Grooved Ware has been recovered from the eroding settlement, while test pits into the large mound produced Grooved Ware ornamented with applied decoration (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Braby, Dockrill, Downes and Richards1995). At these two Sanday sites, a disjunction is evident in settlement between c. 2800 and 2600 cal BC. A similar scenario occurred at Skara Brae, where an earlier nucleated settlement with recessed house architecture, founded in the centuries around 2900 cal BC, may have been abandoned after a relatively short period of habitation, and re-occupied in the twenty-eighth century cal BC (Figure 5).

In the Stenness-Brodgar area of western Mainland, a similar situation has become apparent, with incised Grooved Ware and recessed house architecture appearing with the foundation of the nucleated Barnhouse settlement in the late thirty-second century cal BC. From the outset, however, monumental architecture (house 2) is a dominant component of Barnhouse, a feature that becomes exaggerated with the subsequent construction of the massive structure 8 (Figure 3f). Although the earliest settlement evidence is yet to be found, the Ness of Brodgar seems to share a similar trajectory to Barnhouse, with monumental structures dating to the first centuries of the third millennium cal BC (e.g. Figure 3e).

Thus, across Orkney (including the Stenness-Brodgar area of western Mainland) between the late thirty-second and twenty-ninth centuries cal BC, settlement nucleation accelerates alongside the deposition of substantial midden deposits to create identifiable ‘villages’. At the majority of these villages a disjuncture occurred c. 2800 cal BC, involving abandonment and a spatial shift in settlement. Then, in the twenty-seventh to twenty-sixth centuries cal BC, a process of reoccupation emerged that continues until a final abandonment of villages in the twenty-fourth century cal BC. This phase of occupation involved different house architecture, larger houses and differently made and decorated Grooved Ware. This temporal and spatial sequence is not, however, universal, and at the Bay of Stove, Sanday, the original village was never reoccupied and a massive settlement mound accrued a few hundred metres away. Equally, at Tofts Ness, on Sanday, occupation appears to have continued to the end of the third millennium cal BC.

The later part of this narrative does not include settlements in the Stenness-Brodgar area because something very different happened here. The founding of Barnhouse and the Ness of Brodgar coincided with developments occurring in other parts of Mainland and the outer isles. Monumental construction in and around them significantly drew on the architecture of ‘big houses’ (Figure 3e–f) and may have materialised links and relations beyond Orkney (see Richards Reference Richards2013: 74–78). Unlike many of the other villages, however, these sites were never reoccupied. Instead, from the twenty-eighth century cal BC, the Stenness-Brodgar area appears to have ceased to serve as a significant place of human dwelling. The later history of the Ness of Brodgar involved extensive ‘middening’ and then an episode of large-scale feasting around the remains of the monumental structure 10 (Card et al. Reference Card, Mainland, Timpany, Batt, Bronk Ramsey, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Marshall and Whittle2017); construction of the Ring of Brodgar may have occurred towards the mid third millennium BC (see OSM, Figures S7–8).

Provisional conclusions

Instead of uninterrupted continuity, a much more complex and differentiated sequence emerges. At the island scale, this appears to be a history of interaction between households and relatively small communities. Due to the constant and rapid changes, it is plausible that this was a competitive situation, with rivalries played out in monument construction, forms of material culture and the social space of houses. There is good reason to view the innovations of both passage graves and Grooved Ware as part of local social strategies of differentiation (cf. Sheridan Reference Sheridan, Roche, Grogan, Bradley, Coles and Raftery2004). The foundation of new settlements in areas previously little occupied, such as Barnhouse (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016a), and the constant development of the form and interior spaces of houses (Figures 3a–d & 6) can be considered along the same lines. Perhaps local political tensions and social concerns driving the trajectory towards closer settlement nucleation could not be sustained, despite people investing time and labour in monuments relating to deities, ancestors and origins that stretched well beyond the shores of Late Neolithic Orkney.

The Orkney story is also one of connections throughout, as suggested above for passage graves and stone circles. Local identities may have been constituted in part through far-reaching contacts and relationships; the Late Neolithic world was indeed clearly expansive in nature (Thomas Reference Thomas2010; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016a; Sheridan et al. in prep.). If there is a case for placing the origin of Grooved Ware in Orkney, does the coincidental appearance of the Orkney vole allow us to visualise the direct exchange of ideas or the movement of people from regions where flat-based pottery was already common in the later fourth millennium cal BC (e.g. from northern France to the Alpine foreland)? With the decline of Late Neolithic settlement in Orkney, it is perhaps no coincidence that previous connections and networks also lapsed, as evidenced by the sparse Beaker presence in the archipelago. History had moved elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many colleagues whose cooperation has made the dating reported here possible; Mark Edmonds, Ann MacSween, Lekky Shepherd and Alison Sheridan for constructive criticism of an earlier draft of this paper; and Kirsty Harding for help with the figures. The Times of Their Lives (www.totl.eu) is funded by the European Research Council (Advanced Investigator Grant: 295412), and is led by Alasdair Whittle and Alex Bayliss.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.140