In an increasingly globalised world, there has been an understandable scholarly turn towards the analysis of when, why and how networks of cultural and biological exchange emerged in the past. One of the most ancient and important such networks is the Silk Road (or Roads)—a complicated web of overland trade and travel routes that linked Eastern and Western Eurasia across its continental interior. Although historians have traditionally demarcated the formalisation of these routes in the second century BC, recent archaeological discoveries indicate that plants and animals were first exchanged across Central Asia many centuries earlier. Domestic crops such as wheat, barley and millet began to criss-cross the continental interior during the third millennium BC (Spengler et al. Reference Spengler, Frachetti, Doumani, Rouse, Cerasetti, Bullion and Mar'yashev2014), and some scholarship suggests that the movements of Bronze and Early Iron Age pastoral peoples shaped the development of later trade and travel routes (Frachetti et al. Reference Frachetti, Smith, Traub and Williams2017).

One of the most important driving forces of the early Silk Road was the movement and trade in domestic animals. From the end of the first millennium BC, demand for tall, strong ‘heavenly horses’ (天馬)—bred in the rich Ferghana Valley (modern-day Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) (Figure 1)—prompted major incursions into Central Asia by the Han Empire in China (Cooke Reference Cooke2000). In subsequent centuries, the many branches of the Silk Road delivered high-quality horses to the central plains of China in the tens of thousands. Beyond the horse, other large animal domesticates, such as donkey (Figure 2), mule and camel, helped to shape and sustain travel across Central Asia's extreme environments (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2018). Despite the astonishing scale of these later livestock exchanges, very few archaeofaunal remains are available with which to understand animal economies prior to the first millennium BC.

Figure 1. Iron Age horse petroglyph in the Ferghana Valley near Osh, Kyrgyzstan, showing the tall stature associated with the famed ‘heavenly horses’ (photograph by W. Taylor).

Figure 2. Donkey tethered outside of the modern township of Kabyk, in Kyrgyzstan's Alay Valley (photograph by W. Taylor).

Our project seeks to understand the early prehistory of animal and plant use along the mountain corridors of the ancient Silk Road through fieldwork in southern Kyrgyzstan's high Alay Valley—a large valley linking western China with the Ferghana Valley and the oases of western Central Asia (Figure 3). In 2017, we conducted research at the Alay site, which provides some of the earliest evidence for the occupation of high mountains in western Central Asia. We also initiated survey, identifying more than 15 archaeological site clusters, including habitation sites, rock shelters, kurgans and lithic scatters. Radiocarbon dates from test excavations and material exhumed by recent marmot activity show that these sites date from the Bronze Age (c. 2100 BC) through to the Middle Ages (c. AD 1450), with many habitations yielding a rich artefact assemblage of faunal remains, ceramics and other goods, such as glass and worked wood.

Figure 3. Location of Chegirtke Cave, within the Alay Valley, along with the approximate location of some key branches of the Silk Road, and other important political and geographic locations mentioned in the text (map by W. Taylor).

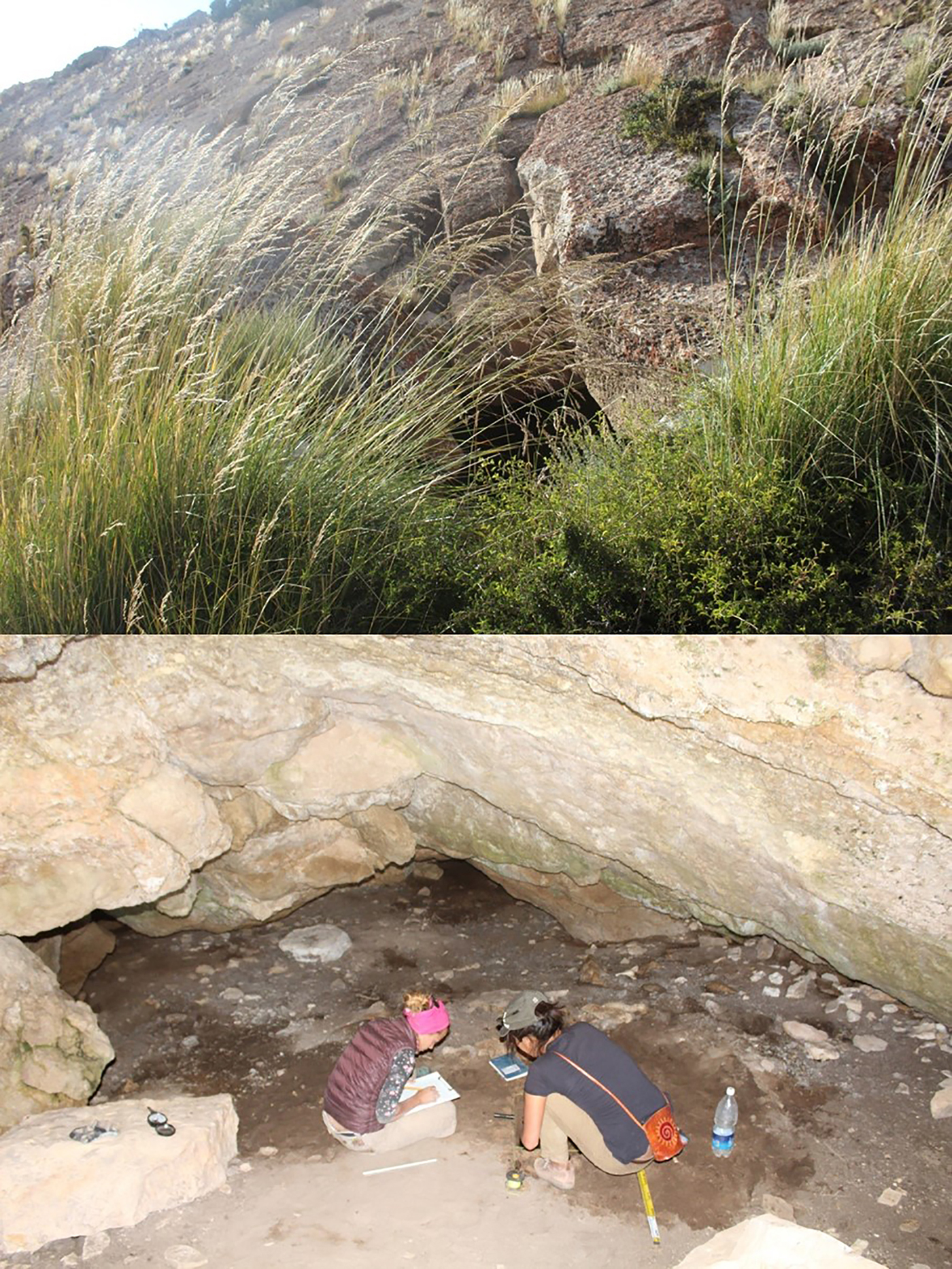

Most significantly, we identified a stratified, multi-component cave site (Figure 4) that may illuminate the early regional history of domestic animal and plant use. This site, known as Chegirtke Cave, contains at least two chambers and revealed Early Holocene, Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (c. 2100 BC) cultural components. Flotation of charred material from a Bronze Age hearth showed a rich archaeofaunal assemblage and carbonised wood with clear vascular structuring indicating a conifer—most probably a juniper shrub. Our results suggest that future archaeobotanical studies at this locality may be promising, and may help to answer important questions, such as whether mountain-dwelling peoples played a role in the early transmission of wheat into China.

Figure 4. Top) exterior entrance to Chegirtke Cave; bottom) researchers preparing for test excavations within one of the cave's two chambers (photographs by W. Taylor).

The central aim of our project, however, is to use cutting-edge techniques from the archaeological sciences to understand the emergence of animal economies. To combat challenges with the identification of animal bones, which in Central Asia are often highly fragmented, our project pairs collagen-based fingerprinting (zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry) with ancient animal DNA (Schubert et al. Reference Schubert, Mashkour, Gaunitz, Fages, Seguin-Orlando, Sheikhi, Alfarhan, Alquraishi, Al-Rasheid, Chuang, Ermini, Gamba, Weinstock, Vedat and Orlando2017), radiocarbon dating and stable isotopes. This multi-method approach promises to illuminate the emergence of herding lifeways and other changes in the use of domestic animals that helped to shape the cultural and physical landscapes of China and Eurasia.