Introduction

Until now, evidence for prehistoric settlement in the alpine region of the Carpathians was almost non-existent. All attempts to identify traces of Palaeolithic settlement in the caves of the Tatra Mountains at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century were unsuccessful (Jura Reference Jura1955). This state of uncertainty ended with the discovery of unquestionable evidence for Magdalenian settlement, which was obtained recently from the first surveys of Hučivá Cave in the Belianske Tatras, Slovakia (49°13′14.8″N, 20°18′37.2″E) (Soják & Valde-Nowak Reference Soják and Valde-Nowak2021) (Figure 1). This especially inspiring discovery was preceded by tentative signs of Magdalenian settlement within the Tatra Mountains (Valde-Nowak et al. Reference Valde-Nowak, Kraszewska and Cieśla2017).

Figure 1. The location of Hučivá Cave (red dot) against the background of the Last Glacial Maximum glacier in the Tatra Mountains: A) a hypsometric map of Slovakia and neighbouring countries (B), and a detailed contour plan (C) (figure by the authors based on data from Zasadni & Kłapyta Reference Zasadni and KŁapyta2014).

Methodological remarks and stratigraphy

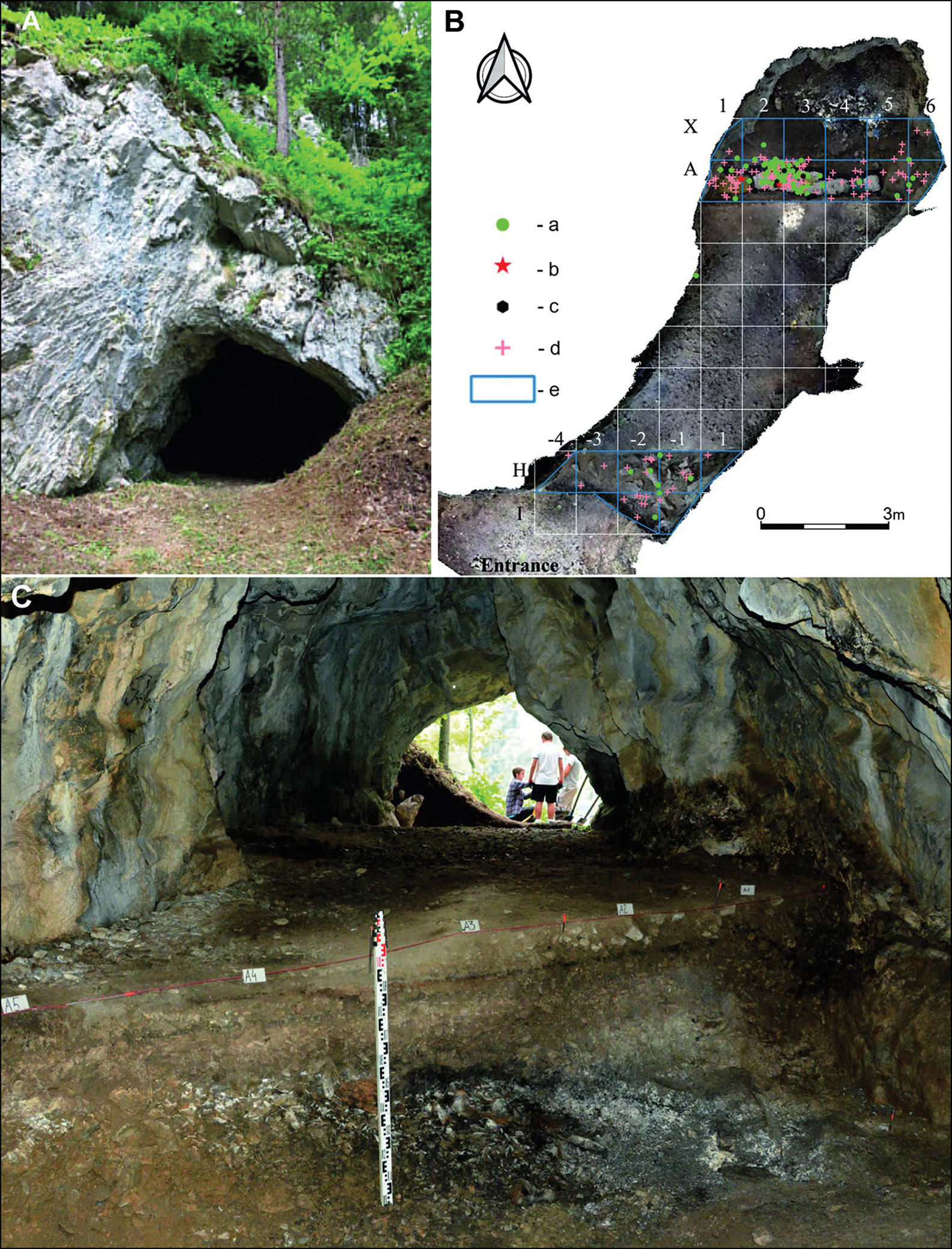

Sediment within Hučivá Cave was excavated in arbitrary 50mm layers, maintaining a grid of 1m2, which formed the basic unit of excavation. The initial excavation consisted of cross-sectioning and expanding significantly an illegally excavated trench that had been previously dug in the chamber by speleologists. Our new trench discovered 1.4m of stratigraphy overlying the chamber floor. Six main layers of clay-rubble were observed within this stratigraphy; the deepest layer (VI) was divided into sublayers, one of which (VIc) documents the remains of a fireplace (Figure 2). Complete and thorough wet sieving of cave sediments, using sieves with a clearance of <1mm, allowed faunal and archaeobotanical remains to be gathered from all strata.

Figure 2. Entrance to Hučivá Cave (A) and planigraphy of Palaeolithic finds (B) on the metre grid of the area covered by the excavations (background is a 3D scan of the interior of the cave); C) traces of a fire visible in the section (photographs by P. Valde-Nowak; scan by M. Cheben; graphic design by U. Bąk and the authors). Legend: a) stone artefacts; b) ochre lumps; c) coal; d) bones; e) excavated area.

Archaeological artefacts

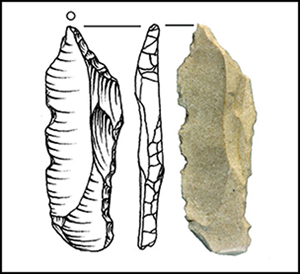

To date, 385 stone artefacts have been discovered, as well as a bone needle preserved in two fragments (Figure 3:12). Many artefacts were made of radiolarite, but there are other raw materials, such as various flints and limnosilicite. The most characteristic tools were shouldered points, as well as examples similar to the massive Creswell and Cheddar-like forms (Bohmers Reference Bohmers1956; Stapert Reference Stapert1985; Maier Reference Maier2015). There were also perforators, including a badly worn specimen with a twisted Zinken-type curved tip. A high degree of en éperon preparation was notable throughout the assemblage. Five lumps of what have initially been identified as ochre were also collected.

Figure 3. Selected stone and bone archaeological artefacts: 1–10) shouldered points and truncations; 11) core; 12) bone needle (illustrations by J. Chowaniak and U. Bąk; photographs by J. Skłucki).

Archaeozoological analysis

The Magdalenian layers produced sparse bones and teeth from approximately 20 small and large mammal species, as well as from a few species of birds. Among the large mammals that could be hunted, ungulates predominate. Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) was represented by fragments of two mandibles belonging to two different individuals. The species affiliation was confirmed by analysis of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) obtained from the specimens. Currently, this species does not occur in the Tatra Mountains, and this is the first confirmation of its past occurrence in the western Carpathians. The presence of another mountain species of chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), as well as deer (Cervus elaphus) and wild horse (Equus ferus), has also been confirmed. Among predators, most of the remains belonged to brown bear (Ursus arctos). More than a dozen bones belonging to different species have traces of cut marks, cracking for marrow extraction and smoothing with stone tools.

Radiocarbon chronology

Two AMS dates were obtained from charcoal from the fireplace: 12 190±60 BP (Poz-114742: 12 316–11 896 cal BC, at 95.4% confidence) and 12 160±60 BP (Poz-114743: 12 260–11 868 cal BC, at 95.4% confidence); the dates were modelled in OxCal v4.2.3 (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Scott and van der Plicht2013) using the IntCal20 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020). Both results point to the Bölling interstadial (GI-1e).

Main issues and outlook

The artefact assemblage obtained from Hučivá Cave, dating to the thirteenth millennium cal BC, is unique due to the lithic forms present—namely shouldered points, which are rarely found in the Magdalenian of Central Europe. They are more clearly present in the Swiss record, where they stand out in techno-assemblage E (Leesch et al. Reference Leesch, Müller, Nielsen and Bullinger2012; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2016), and in Germany, for example at Petersfels and Etzdorf (Pasda Reference Pasda, Valde-Nowak, Sobczyk, Nowak and Źrałka2018; Maier et al. Reference Maier, Liebermann and Pfeifer2020). These artefacts are also very rare in the Polish Magdalenian (Burdukiewicz et al. Reference Burdukiewicz2013; Cyrek et al. Reference Cyrek, Sudoł-Procyk and Czyżewski2020). What draws our attention is the location of Hučivá Cave on the border of the European Magdalenian range (Maier Reference Maier2015; Maier et al. Reference Maier, Liebermann and Pfeifer2020), near to the zone penetrated by the Epigravettian, which was, to some extent, contemporaneous with the Magdalenian. The relationship between those two cultures is still unclear (Wiśniewski et al. Reference Wiśniewski2017; Lengyel et al. Reference Lengyel2021). The location of this Palaeolithic hunting camp, near the border of the Last Glacial Maximum glacier (Zasadni & Kłapyta Reference Zasadni and KŁapyta2014; Makos Reference Makos2015), would almost certainly have affected the availability of game animals (Horáček et al. Reference Horáček, Ložeek, Knitlova, Juřičkova, Sazelova, Novak and Mizerova2015). The results of the Hučivá Cave research project open a wider perspective for the discussion of these issues.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Urszula Bąk for help with the figures, and to the archaeology students from Jagiellonian University. Special thanks to Michał Cheben from the Slovakian Academy of Sciences for scanning the cave chamber.

Funding statement

The Stone Age Man in the Caves of the Tatra Mountains project was financed by Polish National Science Centre grant 2021/41/B/HS3/032. Genetic analysis of the ibex specimens was supported by Polish National Science Centre grant 2020/37/B/NZ8/02595.