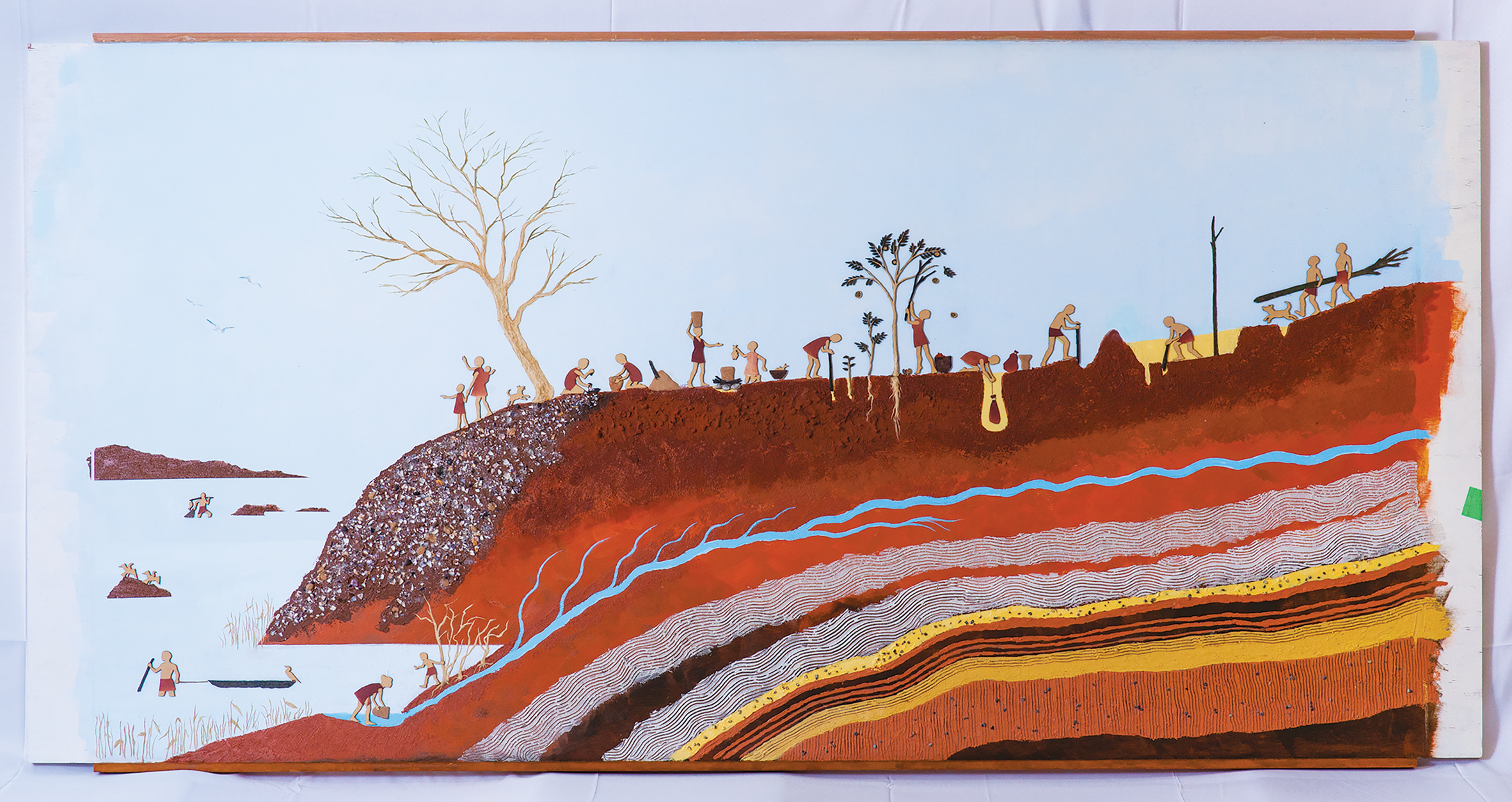

Frontispiece 1. Tree on the shell mound, a collage painting by Aki Sahoko, created as part of the Power of Invisibles project supported by the Toshiba International Foundation and exhibited at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, in 2021. In the decade since the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster that struck north-eastern Japan on 11 March 2011, many archaeological sites have been investigated as part of recovery and reconstruction initiatives. As well as revealing much about the prehistory of the region, these sites have often become the focus for community revival. At the Urajiri shell middens (Early and Middle Jomon periods, c. 4000–2500 BC) in Minami Soma city, Fukushima prefecture, local residents, artists and archaeologists have come together to explore how traces of prehistoric life contribute to renewal and resilience. This spring, Urajiri will host a programme of public art and archaeology events: https://youtu.be/xk4-ruaLDUc. For further details, see https://www.sainsbury-institute.org/project/cultural-properties-loss. Image © Aki Sahoko.

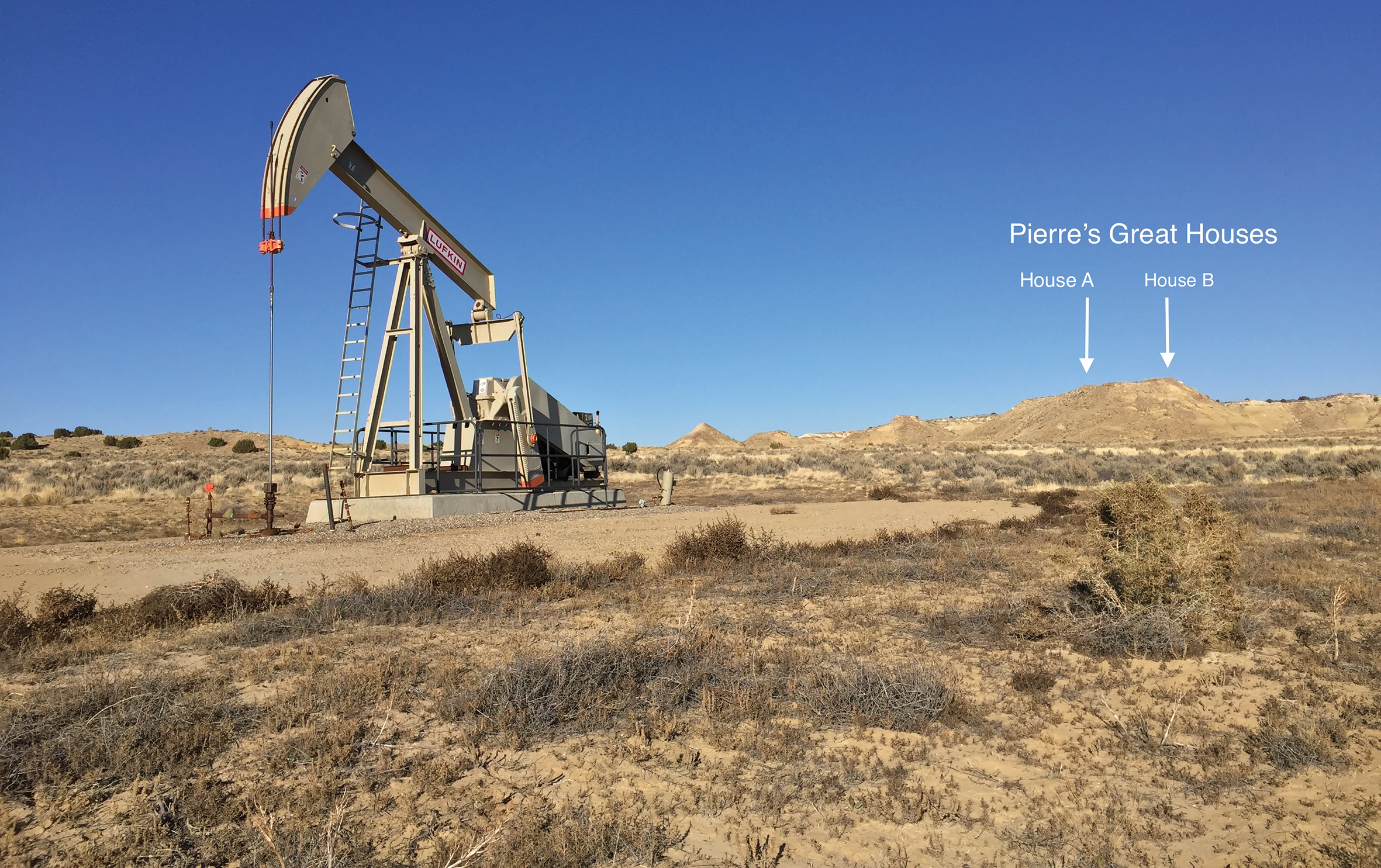

Frontispiece 2. An oil drilling rig approximately 650m south-west of Pierre's community, a site within the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in New Mexico, USA. Legislation banning new mineral extraction leases within a 16km zone around Chaco Canyon stalled in the U.S. Senate in 2019. President Biden has instituted a one-year moratorium on new leases, but 90 per cent of the area north of Chaco Canyon has already been leased, with significant destructive potential for fragile Chacoan archaeology. The greater Chacoan landscape encompasses an area of more than 150 000 square kilometres. Native American descendants, archaeologists, non-profit organisations and environmental activists have joined forces to call for landscape-scale studies before government agencies allow further leases. Learn more at http://read.upcolorado.com/projects/the-greater-chaco-landscape and https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org. Photograph © Ruth M. Van Dyke.

The materiality of COVID-19

![]() The effects of COVID-19 have been many and diverse. The global death toll is moving towards three million and most national economies have slipped into deep recession. The pandemic has also generated new types and uses of material culture and novel forms of social behaviour. From hand-sanitiser stations and plexiglass screens to elbow bumps and one-way supermarkets, how we engage with material culture and with one another has changed. Perhaps the most obvious of these new materialities relates to personal protective equipment, or PPE—plastic face masks, gloves and aprons—as well as the vials and syringes now used to deliver life-saving vaccines. In this issue, Schofield et al. take aim at the massive quantities of ‘COVID waste’ generated in tackling the virus and, in particular, the environmental effects of the improper disposal of this material. With billions of items of plastic waste generated since the start of the pandemic, the authors argue that archaeologists can bring a distinctive perspective to the problem—one that threatens to reverse recent trends away from single-use plastics—by working with other specialists to influence public policy (Figure 1).

The effects of COVID-19 have been many and diverse. The global death toll is moving towards three million and most national economies have slipped into deep recession. The pandemic has also generated new types and uses of material culture and novel forms of social behaviour. From hand-sanitiser stations and plexiglass screens to elbow bumps and one-way supermarkets, how we engage with material culture and with one another has changed. Perhaps the most obvious of these new materialities relates to personal protective equipment, or PPE—plastic face masks, gloves and aprons—as well as the vials and syringes now used to deliver life-saving vaccines. In this issue, Schofield et al. take aim at the massive quantities of ‘COVID waste’ generated in tackling the virus and, in particular, the environmental effects of the improper disposal of this material. With billions of items of plastic waste generated since the start of the pandemic, the authors argue that archaeologists can bring a distinctive perspective to the problem—one that threatens to reverse recent trends away from single-use plastics—by working with other specialists to influence public policy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. COVID waste (photograph by R. Witcher).

PPE can be more than just waste, however; it can also be seen to possess agency, subtly changing our behaviours and other material culture. In France, for example, mask-wearing is reported to have precipitated a decline in the sales of lipstick and an increase in spending on eye make-up.Footnote 1 More generally, COVID-19 has transformed many daily routines and sensory encounters with material culture. Coins and notes have become unfamiliar objects as shops encourage electronic card payments. Indeed, the concept of a shopping trip has become something to be carefully planned, or even avoided altogether by shopping online and home delivery; cardboard packaging might be another characteristic form of Covid waste. For many—although not for the key workers who have kept vital services running throughout the pandemic—homeworking and videoconferencing have become the norm, and the daily commute has been replaced by a walk around the local neighbourhood. Under lockdown in the UK, the conversion of commuters into homeworkers has led to a notable reversal of urban fortunes. The centres of large cities that have driven economic growth over the past decade have seen footfall reduce dramatically, while smaller towns have benefited from people shopping locally. One recent study suggests that the population of London has fallen by 700 000 over the past year as office workers, liberated from the daily commute, leave the capital for cheaper rent and more space elsewhere.Footnote 2

Such changes are dramatic, but are they temporary, awaiting the resumption of business as usual, or do they signal more permanent shifts in behaviour? With the roll-out of vaccines underway—albeit still very unequally available around the world—and with unprecedented economic challenges ahead, the pressure to revert to our pre-COVID habits will be intense. It may therefore be too early to proclaim the pandemic as a tipping point—the beginning of the end of the city as we know it. Yet, if our five-millennium perspective on urbanism tells us anything, it is that cities, both individually and collectively, are never as permanent as their inhabitants believe. Time and again, our ancestors have found solutions to problems—security, access to resources, innovation and power—by choosing to gather and live together in urban settlements. But sooner or later cities become the problem: too dangerous and polluted for their inhabitants, too powerful for their enemies, too slow to adapt to changing circumstances, or simply located in the wrong place. From Babylon to Tikal, we have archaeological case studies of the urban landscapes of demographic decline. But in a world driven by ‘grobalisation’ and the narrative of ever-expanding wealth and population, these historical examples of decline have rarely felt relatable to the present. How does the contemporary city shrink in an age dominated by the ideology of growth? What would these future cities look like? What will they be for? And what does this mean for archaeology in and of these urban landscapes? We have some clues: cities such as Detroit, where population has fallen by over 60 per cent since its peak in the 1950s, or the suburbs of unoccupied ‘ghost’ houses (akiya) in Japan. But these contemporary examples are often dismissed as one-offs, outliers on the ever-upward growth curve, in the same way that the decline of individual ancient cities is often explained away by unique circumstances of hubris, military action or environmental misfortune.

Yet, what if Detroit and its ilk are outliers only in a chronological sense, simply commencing their depopulation and reconfiguration in advance of other cities? For, even if COVID-19 turns out not to be a tipping point in our urban habit, global population projections suggest demographic changes by 2100 of a scale that would significantly reconfigure how we live and interact. A recent study forecasts a global population peak by 2064 of 9.73bn, before falling back to 8.79bn by the end of the century.Footnote 3 Beneath these headline figures are some even more striking trends, with dramatic shifts in age profiles and national populations, such as a halving of numbers in countries such as Spain and Thailand, and even falling by 48 per cent in China. There is still a lot of population growth to come over the next four decades, but if the projected figures are only even vaguely correct, by 2100, many cities especially in Europe and Asia, will look very different. And so will our archaeologies.

First, perhaps, the construction of new office blocks might dry up, along with the developer-funded investigations of deep archaeological deposits that have enriched our understanding of the origins of our urban habit. The stories we tell might therefore also shift—as investigations move away from the centres of great cities of commerce and finance, our archaeological narratives might put less emphasis on globalisation. Next, fewer people will need fewer existing buildings, and those structures surplus to requirement will be abandoned or demolished. Decisions about the demolition of these unneeded buildings will directly influence future narratives of the past.Footnote 4 Those selected for demolition are likely to be the most recent, and often least loved, of buildings such as Brutalist concrete architecture and 1970s shopping centres, perhaps leaving a late twentieth-/early twenty-first-century gap in our urban histories. Many buildings and landscapes, however, will not be demolished, but simply left as they stand. In Islands of abandonment: life in the post-human landscape, Cal Flyn travels to a series of places around the world, from Pripyat near Chernobyl to Paterson, New Jersey, which have been abandoned for a variety of reasons.Footnote 5 Surprisingly, she finds these deserted towns and industrial complexes full of life; in the absence of humans, even the most toxic and polluted of built environments have been recolonised by animals and plant life. But it will not only be cities and industrial landscapes that will be rewilded following abandonment. In a less populated world, rural landscapes will also be given up to the succession of vegetation. Indeed, the industrialisation of agriculture production means that we are already using less space to feed more people; huge tracts of agricultural land across the northern hemisphere have been abandoned over recent decades. The deforestation of rainforests notwithstanding, global tree cover has increased significantly since the mid twentieth century.Footnote 6 These expanding forests have already covered up all manner of evidence for anthropogenic activity, from field systems to extraction sites, tree roots bursting open agricultural terraces and pulling down structures in slow motion (Figure 2). Technologies such as lidar will become ever more important to detect, record and monitor these reforested post-human landscapes.

Figure 2. An abandoned paper mill near Durham reclaimed by woodland (photograph by R. Witcher).

What, therefore, will our future narratives of the past be about? Attention might well shift to the recent past—the astonishing landscapes of peak population and peak carbon of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Perhaps we'll investigate the remains of abandoned airports and the graveyards of outsized cruise ships and jumbo jets, or the endless landscapes of grey warehouses on the urban peripheries, noting them as single-phase monuments to the consumption of ‘stuff’. Alternatively, will the society of 2100 want, or be able, to fund the archaeological investigation of their grandparents’ wasteful world—especially when dealing with the many direct and indirect costs of our ecological recklessness, not least a climate crisis? Already the effects of higher average temperatures and less predictable weather—from wildfires in the Arctic to snow in Texas—are affecting people's lives and livelihoods, as well as the archaeological record. Some communities, for example, have begun to relocate away from eroding coastlines—erosion that is revealing archaeological sites and artefacts faster than they can be documented in locations as diverse as Chesapeake Bay and the Maldives.Footnote 7 Indeed, the combination of significant change in global population size and climate change will likely bring about what Sonia Shah calls the ‘next great migration’, a period of renewed human mobility as individuals and communities move farther and more frequently to find somewhere safe to live, work and thrive: “We've constructed a story about our past, our bodies, and the natural world in which migration is the anomaly. It's an illusion. And once it fails, the entire world shifts”.Footnote 8

Moving with the times

![]() Another impact of COVID-19 is the sharp reduction in the ability of billions of people to move freely, whether around their local community or to travel the world. Compared with 2019, for example, international air-passenger numbers in 2020 dropped by around 75 per cent. Archaeologists have long engaged with the theme of mobility, from the dispersals of hominins to European colonisation. Today, deprived as we are of our freedom to travel for work or leisure, we are arguably even more attuned to the concept of people in motion. Certainly, several of the articles featured in the current issue are concerned, at heart, with the mobility of people in the past. In northern China, Yi et al. use the evidence of composite microblade tools to identify changing mobility strategies during the Palaeolithic–Neolithic transition, arguing for a new combination of larger, more sedentary communities with the increased mobility of individuals within groups. Meanwhile, at the other end of Eurasia, Manninen et al. also turn to lithic evidence to assess the colonisation of Northern Fennoscandia during the Mesolithic. Recent ancient DNA studies have identified two single-event dispersals into Scandinavia before 7500 BC. Here, the authors demonstrate how the lithic evidence indicates the existence of at least six earlier migration events, the earliest commencing before 9000 BC. Insights such as these emphasise the continuing relevance of material-culture-based studies of prehistoric human dispersal alongside genomic studies. As the authors observe, it is essential for archaeologists and geneticists to collaborate in order to bring their distinct but complementary skill sets to questions about the human past. Since 2015, a series of palaeogenomic studies have shone a bright new light on prehistoric human mobility,Footnote 9 invigorating wider debate about the interpretation of the evidence for the movement of people in the past, including the conceptualisation of ethnic, cultural and racial identities and of kinship relations.Footnote 10

Another impact of COVID-19 is the sharp reduction in the ability of billions of people to move freely, whether around their local community or to travel the world. Compared with 2019, for example, international air-passenger numbers in 2020 dropped by around 75 per cent. Archaeologists have long engaged with the theme of mobility, from the dispersals of hominins to European colonisation. Today, deprived as we are of our freedom to travel for work or leisure, we are arguably even more attuned to the concept of people in motion. Certainly, several of the articles featured in the current issue are concerned, at heart, with the mobility of people in the past. In northern China, Yi et al. use the evidence of composite microblade tools to identify changing mobility strategies during the Palaeolithic–Neolithic transition, arguing for a new combination of larger, more sedentary communities with the increased mobility of individuals within groups. Meanwhile, at the other end of Eurasia, Manninen et al. also turn to lithic evidence to assess the colonisation of Northern Fennoscandia during the Mesolithic. Recent ancient DNA studies have identified two single-event dispersals into Scandinavia before 7500 BC. Here, the authors demonstrate how the lithic evidence indicates the existence of at least six earlier migration events, the earliest commencing before 9000 BC. Insights such as these emphasise the continuing relevance of material-culture-based studies of prehistoric human dispersal alongside genomic studies. As the authors observe, it is essential for archaeologists and geneticists to collaborate in order to bring their distinct but complementary skill sets to questions about the human past. Since 2015, a series of palaeogenomic studies have shone a bright new light on prehistoric human mobility,Footnote 9 invigorating wider debate about the interpretation of the evidence for the movement of people in the past, including the conceptualisation of ethnic, cultural and racial identities and of kinship relations.Footnote 10

If the articles mentioned above are primarily concerned with the movement of people, using objects as proxies for prehistoric migrants, several other articles in this issue are explicitly concerned with the mobility of material culture in its own right. In the ancient Andes, for example, Rosenfeld et al. document how the Wari state (AD 600–1000) mobilised a diverse range of raw materials, objects, plants and animals (as well as people), drawing ‘exotic goods’ from distant regions into the polity's heartland. Concentrated at the city of Huari, this rich assemblage was used to define and sustain social differentiation and to legitimise Wari state ideology.

In their article, Pitts and Versluys enlarge the theoretical framework of the mobility of things through the concept of ‘objectscapes’. The authors explore the entanglements of humans and objects and the ways in which the latter can assert their agency. Building on the material turn, the authors demonstrate the transformative power of ‘objects in motion’, with a particular emphasis on periods of intensive globalisation and object standardisation. In contrast, Lull et al. focus on a single type of ‘emblematic’ object—diadems or crowns of precious metal used to express power in Argaric society in Early Bronze Age Iberia. The authors report on a recently discovered grave at La Almoloya in southern Spain; the double burial includes only the sixth such diadem to be discovered and the first for which full contextual information is available. The burial was discovered beneath a substantial building dating to the seventeenth century BC, tentatively identified as a palace or a ‘parliament’, among one of the earliest such Bronze Age complexes yet explored in Western Europe. The discovery offers the opportunity for a reassessment of the ways in which the qualities of humans and objects intertwine in terms of agency and the creation and projection of social power.

Elsewhere in this issue

![]() Also in this issue, we feature a special section on cosmopolitanism in medieval Ethiopia. Guest editor Timothy Insoll introduces the section with an overview of recent research on the archaeology of Christian, Islamic, Jewish and Indigenous communities in Ethiopia. The following articles present the results of fieldwork at the rock-cut church site of Lalibela (Derat et al.), a Muslim cemetery site in Tigray (Loiseau et al.), the Islamic entrepot of Harlaa (Insoll et al.) and an archaeological and ethnographic study of the long-term shifts in connectivity and isolation in the border region with Sudan (González-Ruibal). Ethiopia has a rich and diverse archaeological heritage, but, historically, the attention of both European and local archaeologists has concentrated on early prehistory (e.g. ‘Lucy’ and the Oldowan stone tool sites at Gona in the Afar region), and on the archaeology of the Christian Aksumite kingdom.Footnote 11 With the demise of centralised monarchy and the military rule of the Derg, in recent years, Ethiopia's many different ethnic and religious groups have begun to seek in the country's wealth of cultural heritage a more diverse set of historical narratives.Footnote 12

Also in this issue, we feature a special section on cosmopolitanism in medieval Ethiopia. Guest editor Timothy Insoll introduces the section with an overview of recent research on the archaeology of Christian, Islamic, Jewish and Indigenous communities in Ethiopia. The following articles present the results of fieldwork at the rock-cut church site of Lalibela (Derat et al.), a Muslim cemetery site in Tigray (Loiseau et al.), the Islamic entrepot of Harlaa (Insoll et al.) and an archaeological and ethnographic study of the long-term shifts in connectivity and isolation in the border region with Sudan (González-Ruibal). Ethiopia has a rich and diverse archaeological heritage, but, historically, the attention of both European and local archaeologists has concentrated on early prehistory (e.g. ‘Lucy’ and the Oldowan stone tool sites at Gona in the Afar region), and on the archaeology of the Christian Aksumite kingdom.Footnote 11 With the demise of centralised monarchy and the military rule of the Derg, in recent years, Ethiopia's many different ethnic and religious groups have begun to seek in the country's wealth of cultural heritage a more diverse set of historical narratives.Footnote 12

The outbreak in late 2020 of armed conflict in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia is unwelcome news. Reliable information is still hard to come by and media coverage has been overshadowed by other global events, but reports of massacres and the large-scale displacement of people are emerging, and wider destabilisation in the neighbouring parts of Eritrea and Sudan is a concern. With human life still at risk, it is too soon to know how the region's cultural heritage may have been impacted, but if the violence follows the pattern of recent conflicts elsewhere, it is likely that archaeological sites and monuments will have been affected. Such damage is often intentional, seeking to strike at the symbolic ties between people and territory and to erase the raw materials of social memory. For a country, and a region, that has sought to develop cultural tourism, the conflict is also economically damaging. Recently, for example, the central government nominated the “Sacred Landscapes of Tigray” property for consideration as a World Heritage Site, an ensemble of 121 rock-cut churches, both earlier and more numerous than the better known group at the existing World Heritage Site of Lalibela to the south.Footnote 13 While we await a clearer picture, and an end to the violence, the special section in this issue will hopefully serve to draw attention not only to the archaeology of the Tigray region (Loiseau et al.), but also to the wider archaeology of Ethiopia's cosmopolitan past.

Elsewhere in this issue we take a new look at cremation and belief in early medieval Ireland, and feature a call for better recognition of the legacy of the Second World War in Poland as revealed through the bomb-cratered landscape of the Koźle Basin. In addition, you can head to our website (https://antiquity.ac.uk/open/projgall) to find a new collection of Project Gallery articles, taking us from Albania and Bosnia to China and Tanzania. As ever, we hope that there is something of interest for all.

Finally, with the further postponement of the World Archaeology Congress meeting to 2022 and other major conferences, including the Society for American Archaeology and European Association of Archaeologists meetings, moving to fully virtual formats this year, the opportunities to meet in person over the coming months are greatly reduced. More than ever, therefore, we would encourage you to get in touch to discuss potential submissions or ideas for special sections, to pass on news of projects and initiatives, or to provide feedback on our content and to suggest new areas that we might seek to feature in the future. You can find all of our contact details and social media channels here: https://antiquity.ac.uk/contact. We look forward to hearing from you.