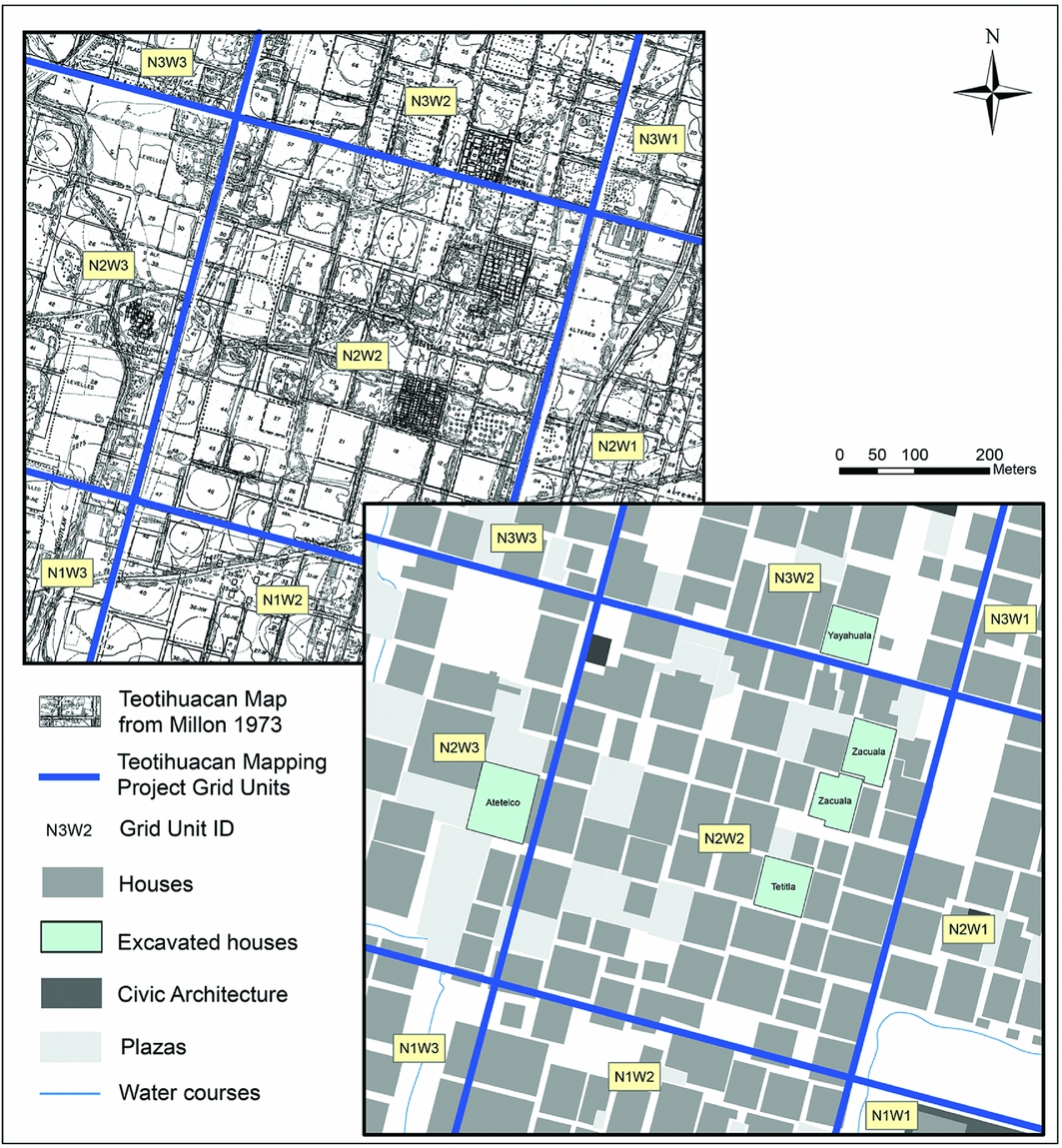

The Teotihuacan Mapping Project (TMP) was a major archaeological project of the twentieth century. In addition to the endlessly reprinted map of the ancient city of Teotihuacan, Mexico (Figure 1; see Millon Reference Millon1973; Millon & Altschul Reference Millon and Altschul2015), the project and its associated artefact collections have supported ongoing research on a wide range of archaeological topics. The future of the project's data, however, must be assured. Over the next two years, the current project, ‘Documenting, Disseminating, and Archiving Data from the Teotihuacan Mapping Project’ (National Science Foundation grant 1723322), will carry out key analyses, standardise datasets and make project data publicly available through the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) (McManamon et al. Reference McManamon, Kintigh, Ellison and Brin2017).

Figure 1. The Teotihuacan Mapping Project map of the ancient city (based on Millon Reference Millon1973)

The TMP

The impact of the city and state of Teotihuacan (c. 100 BC–600 AD), located approxi-mately 30 miles north-east of Mexico City, was felt across much of Mesoamerica through a combination of direct rule in some localities, and cultural influence in others. In the 1960s, the TMP conducted a near-full coverage survey of the city, mapping over 5000 individual structures and collecting surface artefacts from almost all of them. The project also conducted test excavations, with the aim of refining chronological questions and testing the accuracy of the survey data. The project established the size of the city (2000+ ha), its dense urban character, systematic layout and approximate population (80–120k) (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015a). For their achievements with the project, René Millon and George Cowgill were given the highest honour in New World archaeology, the Alfred V. Kidder Award from the American Anthropological Association (in 2004).

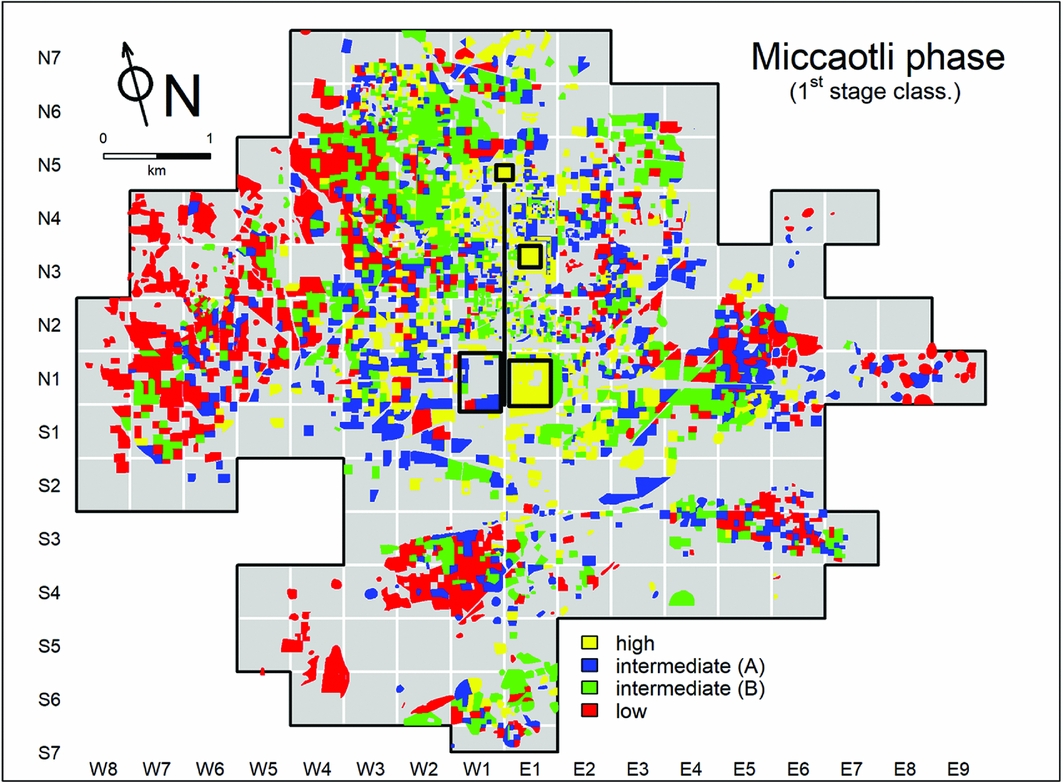

The data produced by the project—particularly the artefact collections and associated digital records—have been central to studies of the ancient city (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015b; Robertson Reference Robertson2015). Surface data were the basis for many key discoveries, such as the identification of two neighbourhoods bearing distinct ethnic identities, and of a large district devoted to ceramic production—all of which were verified by excavation. In subsequent years, studies have used TMP data to reveal much about the internal economic and social organisation of Teotihuacan, including the nature of spatio-temporal variation in wealth and status (see Robertson Reference Robertson2015) (Figure 2). Despite its many successes, however, analysis and publication of TMP survey and test excavation material have been hindered by the sheer scope of the project. A few artefact types still lack basic tabulations, and others have been tabulated but the resulting data not fully analysed. For example, our understanding of the scale of obsidian production in the city, which was briefly debated and then largely dropped (see Clark Reference Clark1986; Spence Reference Spence, de Tapia and Rattray1987), can be improved with new studies on existing collections.

Figure 2. Recent work on the distribution of four wealth/status classes, as inferred from Teotihuacan Mapping Project ceramic data for the Miccaotli phase occupation (adapted from Robertson Reference Robertson2015: fig. 4).

The current project

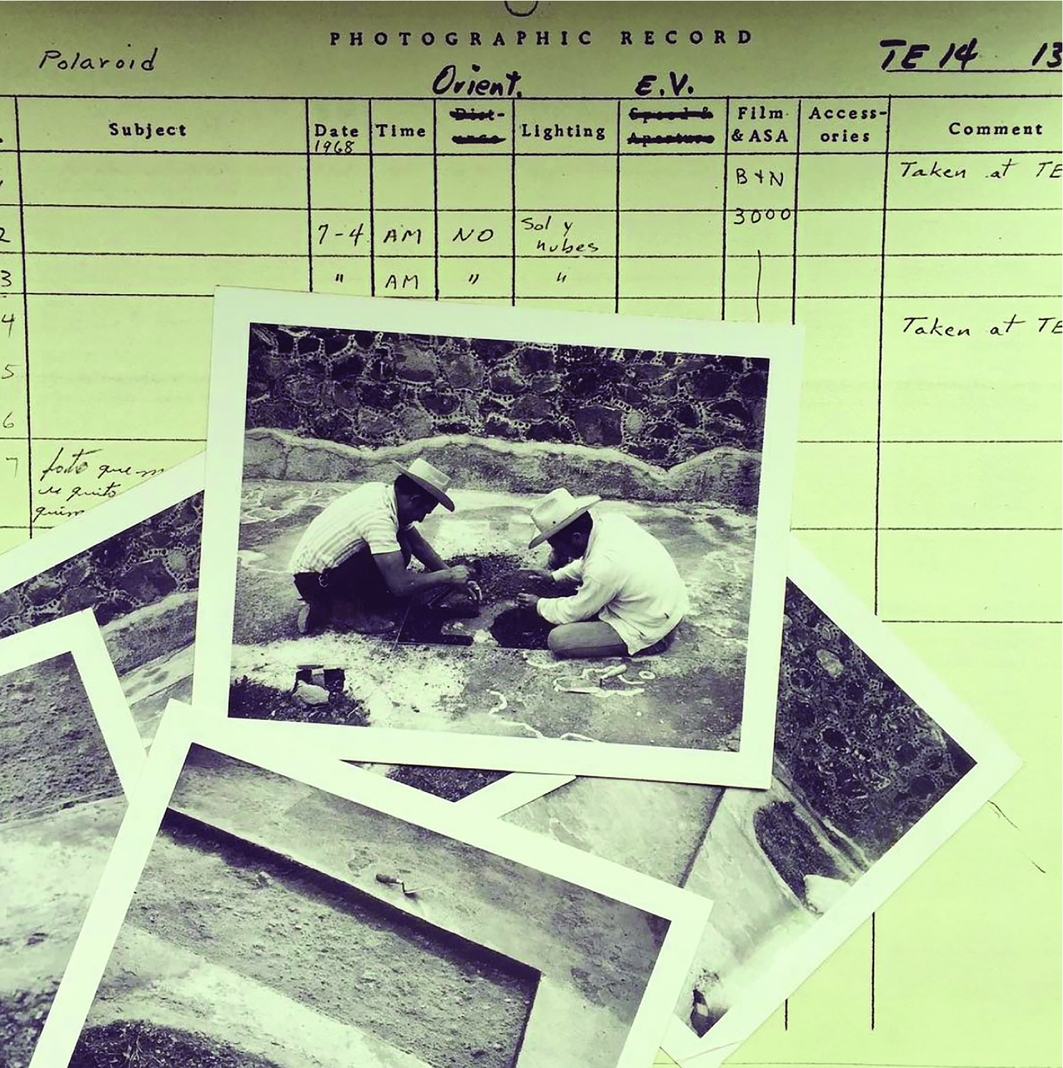

The current project has five goals for the TMP data: 1) completion of the study of crucial artefacts, including those used to infer craft production, exchange and other economic activities; 2) write-up of the TMP test excavations; 3) cleaning, organising and scanning project notes and data files (Figure 3); 4) creation of new GIS shapefiles of the TMParchitectural map to supplement extant files; and 5) depositing the digital files, along with robust descriptive and technical metadata, in a collection (Figure 4) in tDAR, where they can be accessed easily and widely and used for future education, public outreach, research and scholarship.

Figure 3. Historic photograph catalogue and photographs from the Teotihuacan Mapping Project test excavations in 1964.

Figure 4. The tDAR Collection website page for the project.

A brief sample of current work

A brief presentation of recent research illustrates the continuing potential of the TMP data. Robertson and Cabrera-Cortés (Reference Robertson and Cabrera-Cortés2017) analysed the spatial distributions of artefact types potentially associated with maguey sap production. They demonstrated the utility of even the better-studied ceramic collections for answering new questions. A pilot version of the architectural GIS for the city provided comparative data on service provisioning at the site (Dennehy et al. Reference Dennehy, Stanley and Smith2016), showing the continuing value of the purely spatial data generated by the project. The complete version of the TMP GIS is currently under construction (Figure 5). Smith and Paz Bautista (Reference Smith and Paz Bautista2015) completed the first analysis of the almena (roof decoration) fragments collected by the TMP; other artefact categories will benefit from similar renewed attention. The project collections are housed at the Arizona State University Teotihuacan Research Laboratory (https://shesc.asu.edu/centers/teotihuacan-research-laboratory) in San Juan Teotihuacan (Figure 6), and further research is encouraged.

Figure 5. Original Teotihuacan Mapping Project (TMP) detail and current GIS digitisation of the TMP architectural map.

Figure 6. Current artefact storage at the ASU Teotihuacan Research Laboratory.