Background

In 2017, an archaeological evaluation at Puisserguier (Hérault, France) led to the discovery of an exceptional skeleton of the Late Neolithic (3500–2500 BC). The body was deposited at the bottom of a 2.9m-diameter pit, preserved to a depth of 0.3m (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location, plan and general view of pit 1079 (figure by R. Marsac, O. Ginouvez & J. Rouquet).

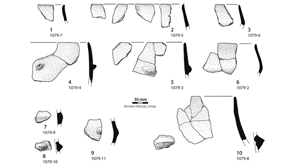

This structure (pit 1079) has been interpreted as the base of a storage cellar. Examination of the typology of pottery finds from this context (Figure 2) dated it to the latest phase of the Verazien culture—a material culture specific to Catalonia and the Languedoc-Roussillon region set between 3500 and 2000 BC (Guilaine & Gandelin Reference Guilaine and Gandelin2023). A radiocarbon measurement carried out on the skeleton confirms its attribution to the Chalcolithic period (between 2700 and 2600 BC). Other finds—such as a copper dagger discovered during ploughing 150m to the east (Figure 3)—belong to the same period.

Figure 2. Typical ceramic vases associated with the skeleton (figure by R. Marsac).

Figure 3. Chalcolithic dagger discovered 150m east of pit 1079 (figure by O. Ginouvez).

A carefully buried decapitated woman?

The skeleton in pit 1079 is of a female, a determination based on the shape of the pelvic bone and later confirmed by a palaeogenetic analysis, aged between 20 and 49 years. The treatment to which they were subjected is remarkable: the head is detached from the spine and placed on the chest, supported by the right hand. This arrangement contrasts starkly with the positioning of the rest of the body, which is conventional for a Neolithic burial (Gandelin Reference Gandelin2021). The skeleton lies supine, with limbs flexed and slightly inclined to the left, and the hands brought to the chest (Figure 4). The respective positions of the head and the right hand are not compatible with natural taphonomic processes; the preservation of the cranio-mandibular connections, as well as those of the wrist and right hand, shows that they were surrounded by soil before decomposition occurred, preventing any involuntary displacement of these bones. (Figure 5).

Figure 4. General view of the burial (photograph R. Marsac).

Figure 5. Detailed view (rotated by 180°) of the head supported by the right hand (photograph by R. Marsac).

This positioning raises questions about when the head was separated from the rest of the body and the modalities of this separation. It seems plausible that the detachment of the head occurred while the flesh maintained the rest of the skeleton in connection. One cannot entirely rule out a desiccation process, resembling mummification, which would have led to the preservation of labile anatomical connections for longer than usual. However, this is unlikely within the chronological, geographical and climatic contexts of this site. In these circumstances, the preservation of labile connections is more likely to indicate the primary nature of this deposit, meaning that it is both the initial and final placement of the deceased (Duday Reference Duday2009), and it must therefore be assumed that the head was severed from the body at the time of death or shortly thereafter.

The condition of the bones, notably the very poor preservation of the cervical spine, did not allow for the observation of any possible marks at this level nor on the mandible, as might be left by cutting off a head from a fresh body. The specificity of this cervical disconnection and the fact that the rest of the skeleton is complete makes the hypothesis of a simple natural decomposition, or even a dislocation in a paradoxical order (Maureille & Sellier Reference Maureille and Sellier1996), difficult to sustain. The most likely explanation is that an active and deliberate cutting of the neck detached the head from the rest of the body.

An unusual case for the period

Burial practices involving the removal of heads are documented at many Neolithic or protohistoric sites but, to date, no comparable example has been found in the Neolithic of southern France. In this context, they mainly appear as a removal of the skull from the burial at a later date, often occurring after complete decomposition of the body (Boulestin Reference Boulestin2012). The Puisserguier burial differs in that the head was intentionally placed in contact with the postcranial skeleton. Similarly, while decapitations have been observed in some burials, often accompanied by dismemberment (Lefranc et al. Reference Lefranc, Reveillas, Thomas, Rocha, Bueno-Ramirez and Branco2015, Reference Lefranc, Denaire, Jeunesse, Boulestin, Bickle and Sibbesson2018), such cases deviate from the typical body positioning observed at Puisserguier.

Despite this unusual treatment, the conventional body position leads us to question the status of this woman and the nature of this deposit. The true sepulchral nature of interments found within reused pits is widely debated (e.g. Jeunesse Reference Jeunesse2010; Schmitt Reference Schmitt2023), especially in instances where these deposits exhibit anomalies such as signs of violence or unusual body positions. They can occasionally be interpreted as indicative of an exclusion of the deceased (Boulestin Reference Boulestin2023). While the burial at Puisserguier may align more with those particular deposits, the meticulous care in its arrangement, conforming to the most common burial posture of the period, suggests efforts to maintain a semblance of normality in death, despite the breach of bodily integrity.

Conclusions

The Puisserguier burial has, to our knowledge, no equivalent elsewhere in France. It is unusual owing to the stark contrast between the apparent intentional disruption of anatomical continuity at the neck and the meticulous post-mortem care afforded to the body. The attention given to the positioning of the head and the right hand likely signifies a deliberate funerary practice. Furthermore, the body's placement in a manner commonly observed in individual Neolithic burials indicates, we believe, the significance attributed to maintaining normalcy in death, despite the remarkable treatment and staging applied to the deceased.