Introduction

After expanding from Central Europe, Linearbandkeramik (LBK) farmers halted in the Northern European Plain. From c. 5500–4000 BC, foragers inhabited the north of Europe, and farmers the south (Klassen Reference Klassen2004). The earliest period of the subsequent Southern Scandinavian Neolithic (Early Neolithic I, 4000–3500 BC) is poorly understood. The Early Neolithic I is the first period of the Funnel Beaker Culture (hereafter TRB) and chronologically falls between the Mesolithic Ertebølle Culture (EBK, 5400–4000 BC) and the TRB Early Neolithic II (3500–3300 BC) (Table 1). Proposed explanations for the adoption of farming in this region include population growth, changes in resource availability, social change or some combination of these (Fischer Reference Fischer2002). Hypotheses about the mechanisms for such change can be grouped as migrationism, indigenism and integrationism—similar to those advanced in relation to the Neolithic Transition across Europe. Migrationism proposes the swift introduction, over just a few generations, of new technologies by incoming farmers. In contrast, indigenism argues that farming was introduced more gradually, with hunter-gatherers as the primary actors, obtaining new ideas and technologies from neighbouring farmers. Integrationism represents a middle ground, combining both migrationism and indigenism. Implicit in both indigenism and integrationism is that it is possible for hunter-gatherers to learn how to farm. The debate therefore ultimately centres on the role of local foragers.

Table 1 The chronology of the Neolithic Transition in Southern Scandinavia.

In this paper, we critically examine the late EBK (c. 4400–4000 BC) and the early TRB, the Early Neolithic Ia and Ib (4000–3800 BC and 3800–3500 BC) of Southern Scandinavia (here inclusive of northern Germany and Poland) (Table 1; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014: 5). We consider the relationship between the last foragers and the first farmers, focusing on evidence for continuity and change, and its chronology. We also reconsider the overall framework for understanding settlement, and specifically the relationship between settlement sites and hunting stations. In comparison with the archaeological and ethnographic record of other regions, we present the case that the transition to farming was a process ongoing in the Early Neolithic I.

Change in the late fifth and early fourth millennia BC

From c. 4400 BC, limited numbers of Neolithic artefacts appear in Southern Scandinavia. While not the start of the Neolithic, this sparse evidence may indicate the beginning of a process of expanding contact between foragers and farmers. At the site of Flintbek in Schleswig-Holstein, for example, a pit filled with short-necked funnel beakers, flake cores and scrapers has been 14C dated to between 4300 and 3900 BC (Zich Reference Zich1993). It is thus one of the earliest discoveries of funnel beaker ceramics in northern Germany.

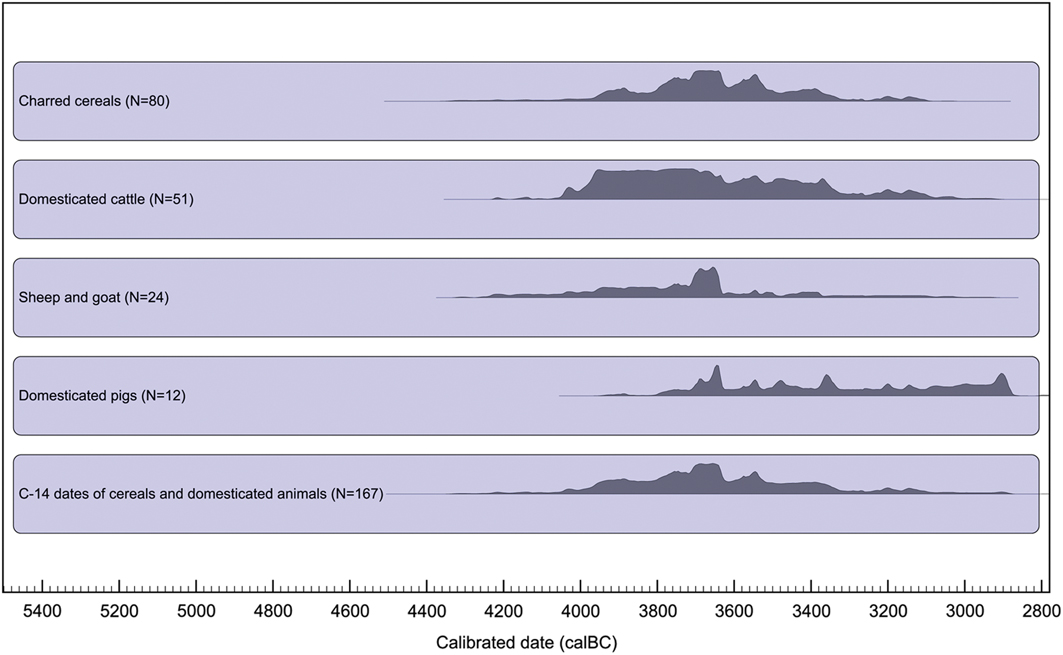

Evidence for farming becomes widespread from c. 4000 BC, documented through compiled 14C dates of charred cereals and domesticated animals (see Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014; Figure 1). Late EBK pottery, adzes and T-shaped antler axes disappear, and TRB material culture, including short-necked funnel beakers, clay discs and spoons, pointed-butted flint axes and battle-axes, appears. Major changes in lithic production include a general shift from blade tools to flake tools, and the replacement of adzes with polished pointed-butted axes (Stafford Reference Stafford1999; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2012). Other developments include two-aisled houses and flint mines (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014).

Figure 1 Available 14C dates for the arrival of domesticates to Southern Scandinavia (see Karlsen et al. Reference Karlsen, Nylén, Ros, Anttila, Runeson and Lihammer2013; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014; Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Artursson and Brink2016; Gron et al. Reference Gron, Montgomery, Nielsen, Nowell, Peterkin, Sørensen and Rowley-Conwy2016; Nielsen & Nielsen in press and references therein. See Table S1 in the online supplementary material for the individual dates). Calibration using OxCal v4.3.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009).

A change in symbolic behaviour is also apparent. The deliberate deposition of material culture is almost non-existent during the EBK (although see Karsten Reference Karsten1994; Koch Reference Koch1998; Berggren Reference Berggren2007), so deposits of many pointed-butted axes and short-necked funnel beakers during the TRB document a significant change (Klassen Reference Klassen2004; Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck2010; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). Some 200 years later, deliberate cattle sacrifice appears, wherein animals were dispatched with one or several blows to the forehead (Price & Noe-Nygaard Reference Price and Noe-Nygaard2009). Such intentional deposits could be seen to demonstrate continuity between the last EBK and the earliest TRB at places such as Hindbygården (Berggren Reference Berggren2007), but, generally, evidence for EBK deposition is limited.

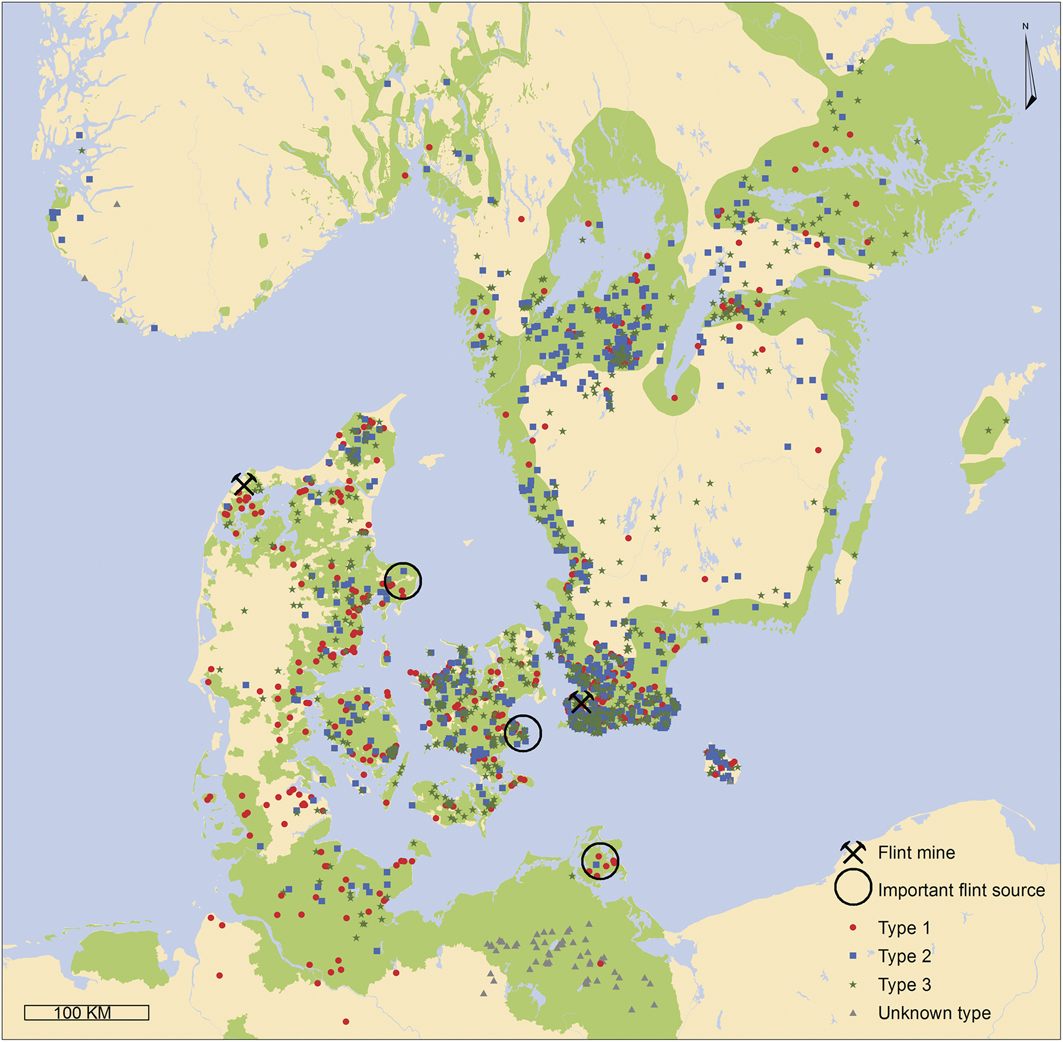

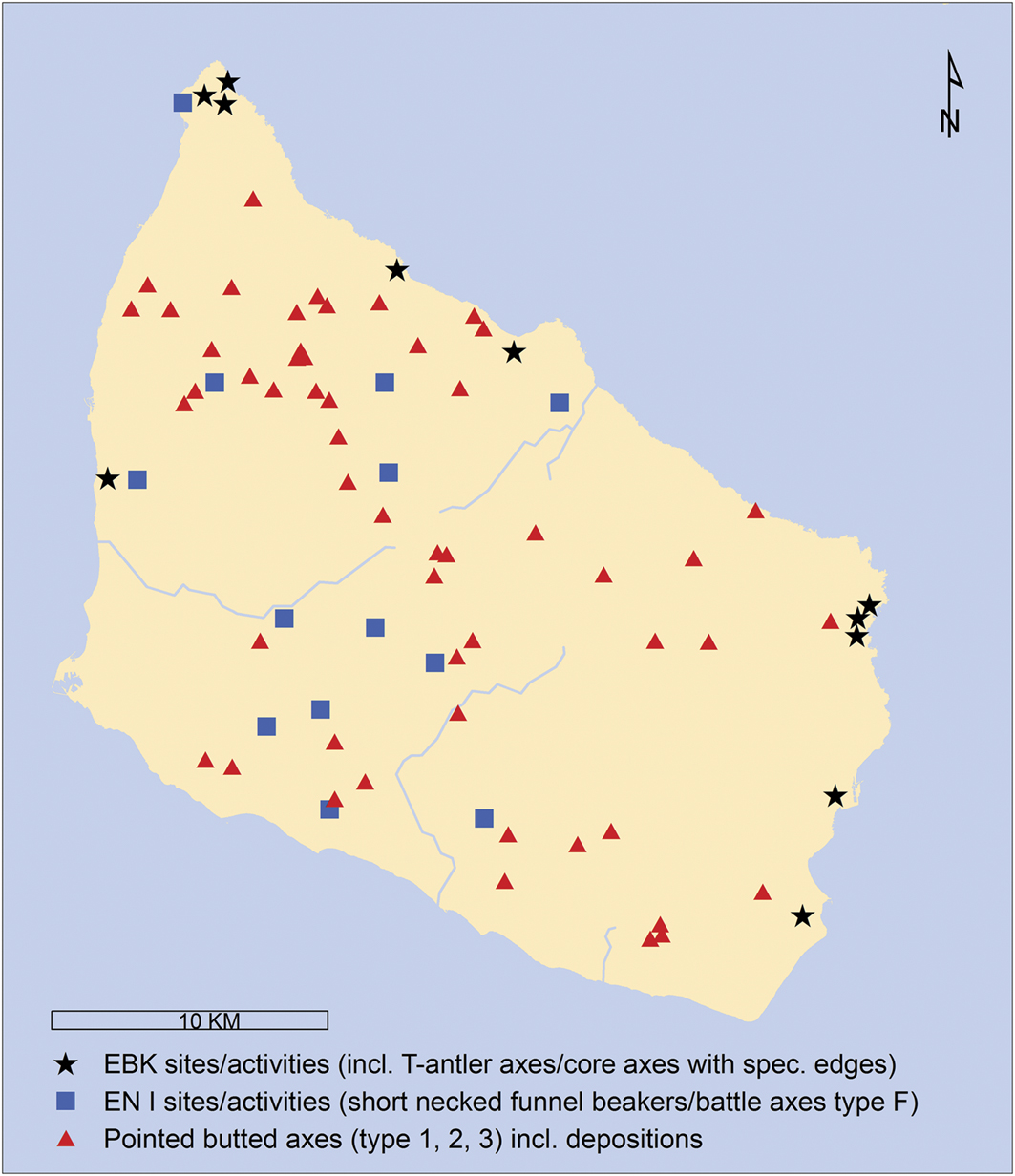

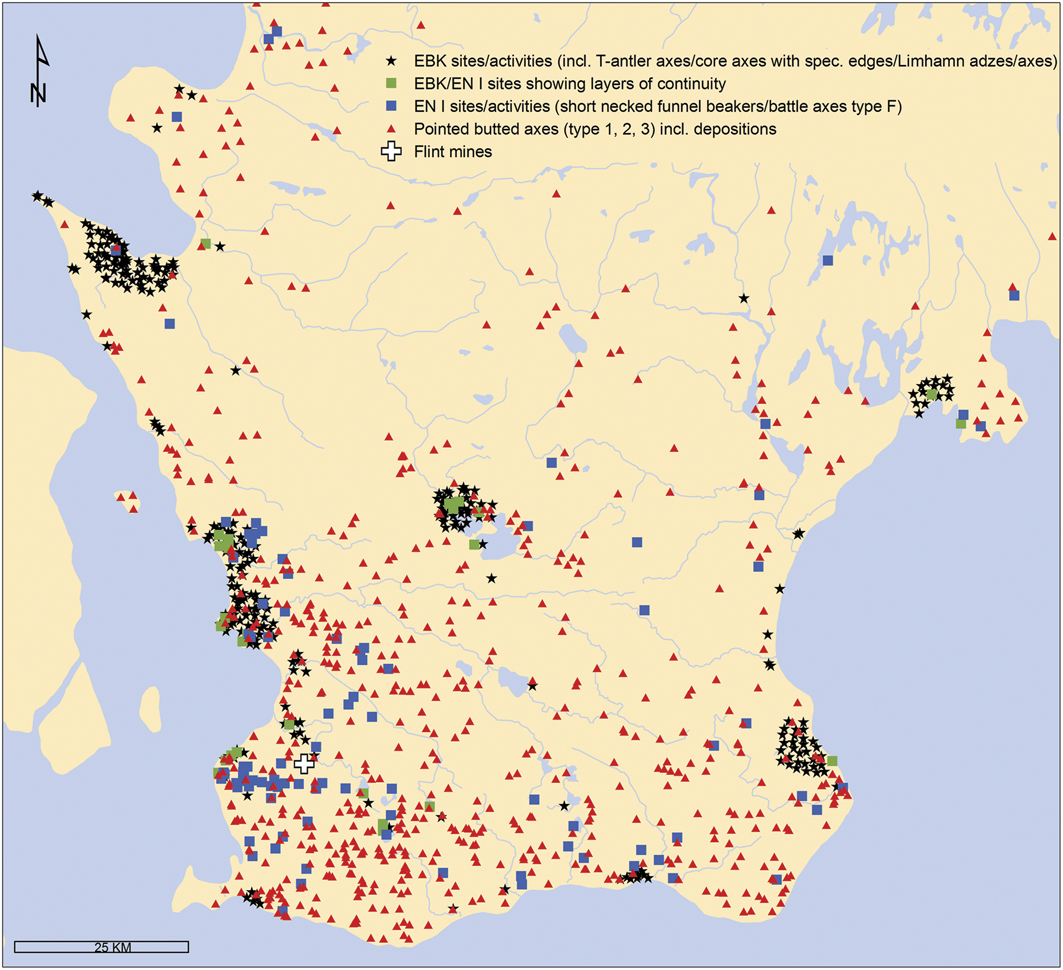

The most profound change appears to concern human diet (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Olsen, Richards, Heinemeier, Sveinbjörnsdóttir and Bennike2007), with a near-complete shift from marine to terrestrial foods. In Denmark, however, there are currently only two humans securely dated to the Early Neolithic from coastal sites, one each from Sejerø and Dragsholm, the former demonstrating a marine diet and the latter terrestrial (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Olsen, Richards, Heinemeier, Sveinbjörnsdóttir and Bennike2007). Several other humans also indicate strongly terrestrial or marine diets, although they could be either Late Mesolithic or Early Neolithic, depending on the marine reservoir correction and the 2σ ranges (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Olsen, Richards, Heinemeier, Sveinbjörnsdóttir and Bennike2007). While such a sharp dietary shift is not universally accepted at the outset of the Neolithic (see Milner et al. Reference Milner, Craig, Bailey and Andersen2006), the evidence does support a dietary shift at some point during the Early Neolithic I, and the isotope values show that diet was predominantly terrestrial from c. 3800 BC. Linked to this shift in diet, there is also strong evidence for change in settlement organisation, with a new type of inland site located on easily worked arable soils. A recent survey of the distribution of pointed-butted axes, dated to 4000–3700 BC, illustrates that the earliest farmers preferred these soils which are mostly found in areas with formerly limited EBK habitation (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014) (Figure 2). Echoing the location of sites in areas of workable soils, plough marks provide direct evidence of Early Neolithic I cultivation. Some examples have been found beneath later long barrows, indicating that ploughs were in use from the beginning of the Neolithic (Beck Reference Beck2013).

Figure 2 The distribution of pointed-butted flint axes from the Early Neolithic overlaying current and historic arable land (green) (after Odgaard Reference Odgaard1999; Krings Reference Krings2010; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014).

Archaeobotanical data offer further insights. Pollen analyses from Scania, the southernmost region of Sweden, show concentrations of charcoal dust dating to c. 4000 BC, possibly indicating slash-and-burn cultivation (Digerfeldt & Welinder Reference Digerfeldt and Welinder1989). Other pollen diagrams from c. 4000 BC show higher concentrations of ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolate) and birch (Betula sp.), which may indicate a fallowing strategy (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). Elevated δ15N values of charred cereal grains from Stensborg in Sweden dating to the later Early Neolithic Ib confirm the selective application of animal manure, indicating an integrated agrarian package (Gron et al. Reference Gron, Gröcke, Larsson, Sørensen, Larsson, Rowley-Conwy and Church2017). As for livestock, carbon and oxygen isotope analyses of sequentially sampled cattle tooth enamel indicate that animals were born throughout the year (Gron et al. Reference Gron, Montgomery and Rowley-Conwy2015). The dietary isotope analyses of a variety of wild and domestic herbivores further show that cattle were not living or being fed in forests (Gron & Rowley-Conwy Reference Gron and Rowley-Conwy2017), but were instead living in open anthropogenic environments. Lastly, strontium isotope analyses suggest the movement of cattle over considerable distances by boat (Gron et al. Reference Gron, Montgomery, Nielsen, Nowell, Peterkin, Sørensen and Rowley-Conwy2016), indicating a community of interconnected farms.

In sum, the earliest farming of Southern Scandinavia was a sophisticated undertaking featuring manuring and crop production, but without widespread forest clearance (Regnell & Sjögren Reference Regnell and Sjögren2006). The data therefore speak to an integrated, landscape-wide system of small-scale farming from its outset—a clean break from a Mesolithic way of life.

Continuity in the late fifth and early fourth millennia BC

As well as change, there is also remarkable evidence of continuity between the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic. The lithic toolkit found at the earliest TRB sites is almost indistinguishable from its EBK counterpart, and the production of blades and flake axes continues into the Early Neolithic (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1985; Andersen Reference Andersen1991; Fischer Reference Fischer2002). Furthermore, the earliest characteristically Neolithic polished flint pointed-butted axes may have developed from EBK core axes, and some axe types and manufacturing techniques more characteristic of the EBK persist into the TRB (Jennbert Reference Jennbert1984; Ravn Reference Ravn2011). Similarly, some of the earliest TRB ceramics show similarities with Mesolithic vessels and are hard to differentiate (Andersen Reference Andersen2011). Charred food crusts from ceramics also show continuity, demonstrating a continuation of the cooking of marine foods (Craig et al. Reference Craig, Steele, Fischer, Hartz, Andersen, Donohoe, Glykou, Saul, Jones, Koch and Heron2011).

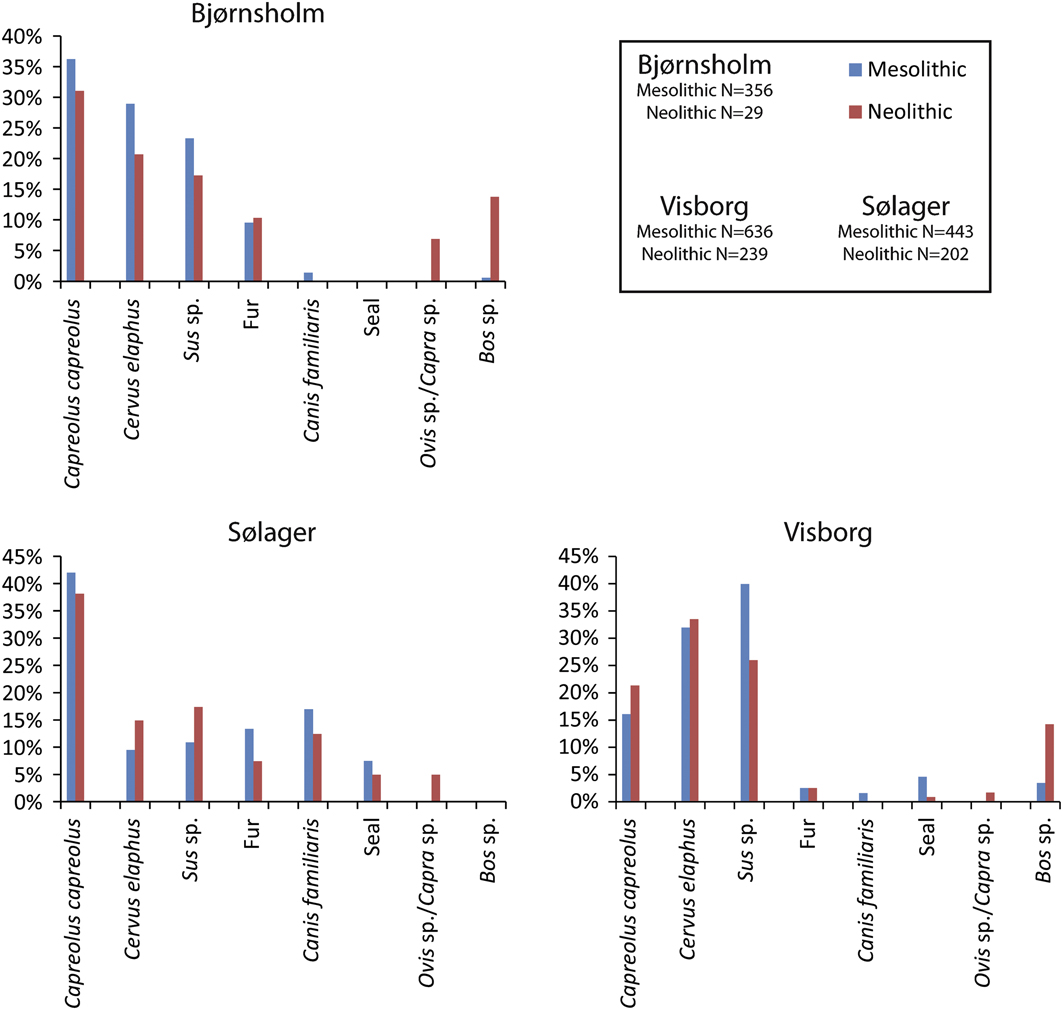

Continuity of settlement between the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic is documented by persistent occupation at a number of EBK kitchen middens, with Early Neolithic I activity directly overlying Mesolithic layers (Andersen Reference Andersen2004). At several of these sites, the faunal material has been successfully assigned to either the Mesolithic or Neolithic phases—most notably at Visborg, Bjørnsholm and Sølager (Skaarup Reference Skaarup1973; Bratlund Reference Bratlund1993; Enghoff Reference Enghoff2011) (Figure 3). At all of these sites, and in both the EBK and TRB, wild species dominate. The overall impression is of largely unchanged local subsistence strategies (Figure 3), except for the low-level inclusion of domestic species in the Neolithic layers (see below).

Figure 3 Mesolithic vs Neolithic fauna at Bjørnsholm, Sølager and Visborg (Skaarup Reference Skaarup1973; Bratlund Reference Bratlund1993; Enghoff Reference Enghoff2011). Sample sizes indicate number of identified specimens. Table omits birds, amphibians, rodents and fish, as well as tentative or mixed identifications save for Sus sp. and Bos sp., where wild and domestic forms are grouped. Seal species and caprines (Ovis sp./Capra sp.) are grouped. Fur animals include Martes martes, Lynx lynx, Meles meles, Mustela putorius, Castor fiber, Lutra lutra, Felis silvestris, Vulpes vulpes and Canis lupus.

Studies from the kitchen middens also show that most of the layers dated to 4000–3700 BC contain limited evidence associated with farming in the form of charred grains, clay discs (baking plates) and grinding stones (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). Only later Early Neolithic kitchen middens layers dated to 3600–3300 BC have yielded these artefacts. The midden evidence for continuity from the Mesolithic to Neolithic is unassailable.

Settlement and hunting stations

The conflicting evidence of continuity and change has resulted in an uneasy compromise within existing explanatory models. Since the 1970s, two types of Early Neolithic I sites have been recognised: settlements and hunting stations (or ‘catching sites’) (Skaarup Reference Skaarup1973; Johansen Reference Johansen2006). Among several differences between these types, including location, topography and size, a primary distinction concerns the composition of the faunal assemblages. Despite difficulties differentiating some wild from domestic species, hunting stations are dominated by wild animals and settlement sites by domestic ones (Rowley-Conwy Reference Rowley-Conwy1995; Table S2). Due to their shared TRB material culture, however, it has always been assumed that the same group of people occupied the two site-types with the ubiquitous—but low-percentage—presence of domesticates attributed to provisions brought to hunting stations (Skaarup Reference Skaarup1973; Johansen Reference Johansen2006). Yet is this probable? The ethnohistory of European-indigenous contact offers some perspective. In the seventeenth-century Massachusetts colonies of North America, livestock were often caught in Native American traps intended for deer, and local indigenous inhabitants killed or stole cattle for subsistence, retribution or by accident (Anderson Reference Anderson1994). Furthermore, domestic species including cattle, pigs and horses commonly escaped and became feral at this time (Gray Reference Gray1933). This was so common that in Florida, the hunting of feral livestock became a reliable source of food; elsewhere, such hunting had to be regulated by colonial officials (Gray Reference Gray1933). By extension, it is possible that domesticates at Early Neolithic I hunting stations were animals that were hunted, trapped or stolen—something that possibly occurred in the EBK (Zeder & Rowley-Conwy Reference Zeder and Rowley-Conwy2014). Similarly, the low proportion of wild species at the settlement sites is consistent with those of immigrant frontier farmers elsewhere in Neolithic Europe and in the ethnohistoric record. LBK faunal assemblages usually comprise less than 10 per cent wild animals and, more broadly, less than 25 per cent in Early Neolithic Europe (see Bickle & Whittle Reference Bickle and Whittle2013; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Downey, Colledge, Conolly, Stopp, Dobney and Shennan2013). Eighteenth-century South Carolina frontier farms show a similar pattern. These settlements were located away from colonial townships in the backcountry, with economies based primarily on cattle husbandry (Groover & Brooks Reference Groover and Brooks2003). At sites of this type, domestic fauna dominate assemblages, with wild game contributing approximately 20–30 per cent.

If faunal assemblages are different, however, the presence of similar material culture at these two site types requires explanation. It is clear that distinct groups can share a material culture. For example, around the time of European contact in the eastern USA, Mohawk and Mahican ceramic traditions were shared, even though groups had different social and political affiliations and spoke different languages (Grumet Reference Grumet1992). Similarly, ethnographic evidence for the transfer of technology and material culture between populations, including foragers and farmers, is also common (Moorehead Reference Moorehead1966; Yin Reference Yin2006). For example, the neighbouring farmers of the last remaining hunter-gatherers of Borneo, the Penan, tried to persuade the latter to start farming (Nicolaisen Reference Nicolaisen1975, Reference Nicolaisen1976). Some Penan tried to grow rice but gave up, sometimes abandoning their fields near maturation in favour of pig hunting—a higher-prestige activity. That they did not return to harvest the rice suggests that they were less interested in food production than in closer social relations with the farmers through marriage alliances and new material culture (Nicolaisen Reference Nicolaisen1975, Reference Nicolaisen1976). Native Americans in the Southeastern USA did not adopt domestic animals until several centuries of contact with Europeans had passed (Pavao-Zuckerman & Reitz Reference Pavao-Zuckerman and Reitz2006). Elsewhere, the process took only decades. The seventeenth-century New England Wampanoag, for example, adopted pigs after 30 years—encouraged by deforestation, which reduced the availability of game (Anderson Reference Anderson1994). This illustrates a wider trend in seventeenth-century New England, in which Native Americans selectively adopted pigs over other domesticated species, usually after decades of contact (Anderson Reference Anderson1994).

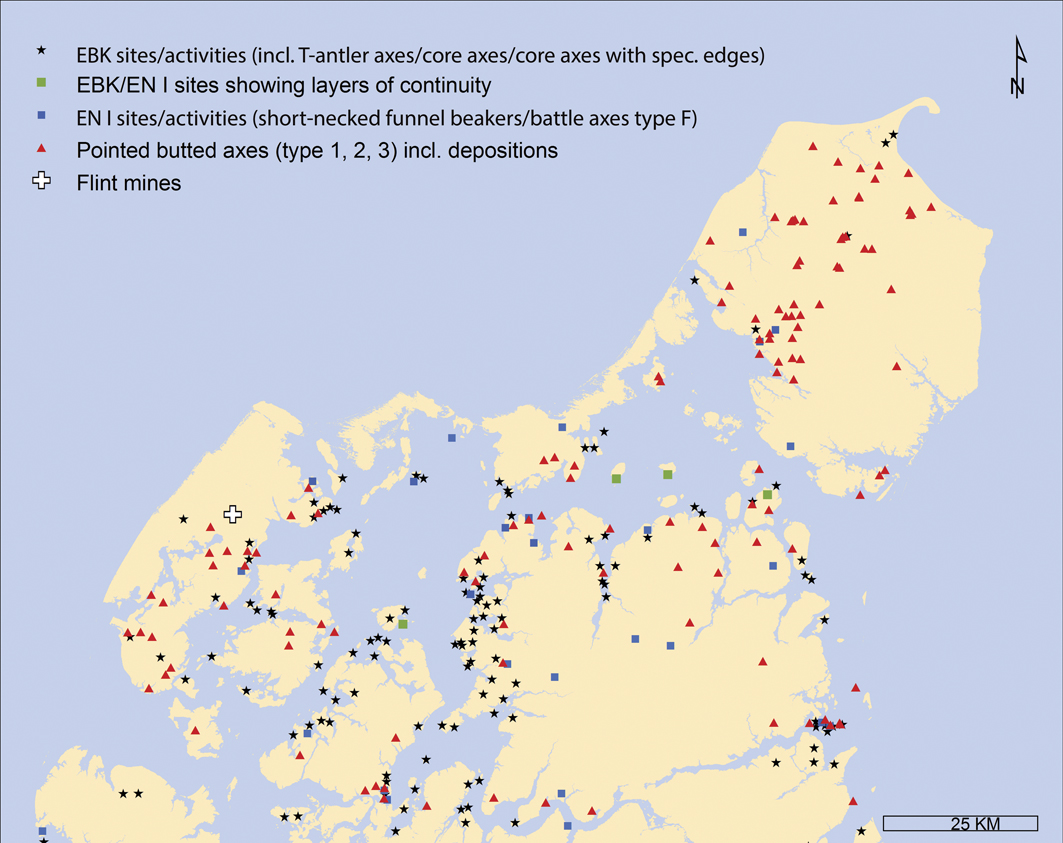

Returning to the Neolithic Transition in Southern Scandinavia, these parallels suggest no reason to assume that the adoption of domestic animals by indigenous groups would have happened quickly. Further, it is equally possible to assume that foragers occupied hunting stations and farmers the settlement sites, as it is to assume that commuting farmers occupied both. In practice, each of these scenarios could have occurred simultaneously in different areas, depending on the social engagement between the hunter-gatherers and farmers. It is perfectly plausible that some regions had two population groups, while others had one moving between inland and coastal areas. This plurality is, in fact, precisely what is observed in the archaeological record. The reason may lie in biogeography. Long, relatively straight exposed coasts are much less productive than heterogeneous coastal environments with a large spectrum of ecosystems (e.g. estuaries, peninsulas, straits, islands and the like) (see Paludan-Müller Reference Paludan-Müller1978). Indeed, it seems that the transition was abrupt on Bornholm (Figure 4) and in Scania (Figure 5), places with long, exposed coasts, and with a quick replacement of foraging with farming corresponding to a shift from coastal to inland settlement (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009). In contrast, in northern Jutland, with its many islands, inlets and estuaries, both coastal and inland settlements occur in the Early Neolithic (Figure 6).

Figure 4 The shift from coastal to inland settlement on Bornholm, Denmark (see Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014 and references therein).

Figure 5 The shift from coastal to inland settlement in Scania, Sweden (see Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014 and references therein).

Figure 6 Mesolithic and Neolithic coastal settlement in north Jutland, Denmark (see Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014 and references therein).

A chronological model

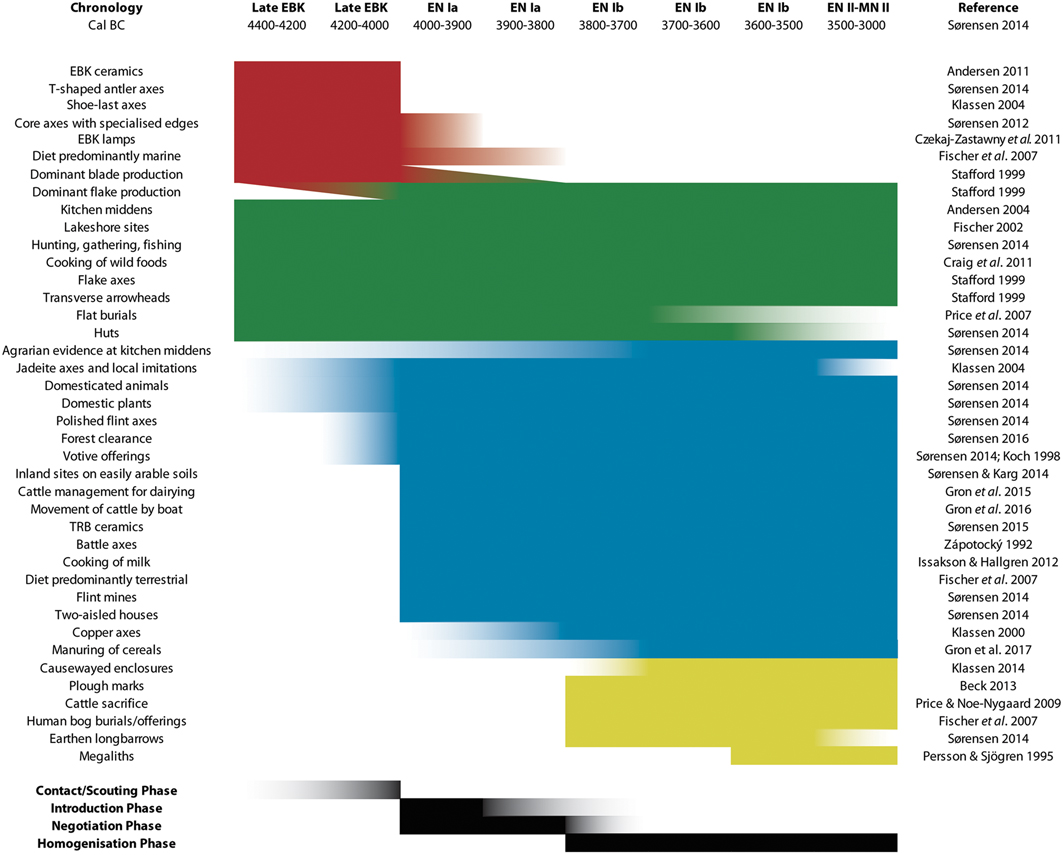

If foragers and farmers subsisted side by side, what does this mean for the Neolithic Transition? It is not only the presence or absence of continuity that matters, but its timing and duration. Both change and continuity in subsistence and material culture from the EBK through the Early Neolithic I can be traced chronologically. Figure 7 shows a clear relationship between the gradual introductions of new practices concurrent with the gradual disappearance of old ones. As such, there is no reason to expect an abrupt demographic and economic replacement c. 4000 BC. We propose that the earliest centuries of the Funnel Beaker Culture were a period of cultural and economic mixing and negotiation between the last foragers and the first farmers. This scenario accounts both for the idiosyncrasies within the early data and for the subsequent emergence of a coherent TRB starting in the Early Neolithic II. It implies that an entirely new understanding of the culture-history of Scandinavia in the earliest years of the Neolithic is needed. Questions that consequently arise include: how long did this situation persist? How much contact occurred and how often? Should we expect genetic exchange between farmers and foragers?

Figure 7 The chronological development of the Early Neolithc I (red = disappearance; green = continuity; blue = change; and yellow = subsequent developments). Dominant blade and flake production are connected as the toolkit is similar.

Any widespread cultural or economic duality could not have persisted longer than the Early Neolithic I. After the introduction of domesticates there is a gradual reduction in hunting and foraging activities, and the appearance of new cultural practices. These include cattle sacrifice, the construction of long barrows and new forms of material culture, as well as the increasing frequency of artefacts associated with cereal agriculture. As most of these developments are in evidence by c. 3700 BC, we suggest that any duality had largely disappeared by this time. Four phases can be identified (Figure 7):

1) Contact/Scouting phase (from c. 4400 BC)

2) Introduction phase (from c. 4000 BC)

3) Negotiation phase (c. 4000–3700 BC)

4) Homogenisation phase (after c. 3700 BC)

The Contact/Scouting phase starts c. 4400 BC, during which the first signs of the Neolithic emerge. Although this is not the Neolithic proper, it represents the initiation of contacts that will later facilitate the movement of incoming farmers. From this period, rare finds of Neolithic origin occur, including impressions of cultivated grains in EBK ceramics and the earliest examples of TRB pottery and polished axes as isolated finds. These suggest direct contact between Neolithic farmers and EBK hunter-gatherers.

The Introduction phase marks the start of the Neolithic in Scandinavia and the Funnel Beaker Culture in the region. It is during this phase that initial immigrants arrived from elsewhere, bringing certain forms of material culture and domesticated plants and animals. Considerable flexibility in the model is required with regard to scale and duration: this phase may have lasted as late as c. 3700 BC, or only for a few decades. Regardless, there is little evidence to suggest any persistence of Mesolithic practices beyond c. 3700 BC, and any incoming population movements may have been restricted to only a short time after c. 4000 BC, with subsequent developments attributable to internal processes.

The Negotiation phase also starts at the very beginning of the Neolithic, concurrent with, but perhaps persisting longer than, the Introduction phase. As with the Introduction phase, the duration of this phase cannot be known. During this period, both foraging and farming strategies were practised (see Rowley-Conwy Reference Rowley-Conwy2004), with regional variations, and with cultural negotiation between populations. This negotiation phase almost certainly ended c. 3700 BC, marked by the appearance of new forms of material culture and practices, such as long barrows, causewayed enclosures, cattle sacrifice and changes in the prevalence of agricultural equipment within shell middens. Foragers and farmers appear to share material culture, but not subsistence strategies, with the farmers based at settlement sites and foragers, descended from EBK groups, at the hunting stations. Contact is certain, and genetic exchange probably occurred. Newly arrived TRB material culture hybridised quickly with EBK forms, with changes to settlement and subsistence following later. Ethnographic comparisons predict exactly this sort of progression, with material goods widely exchanged upon contact, and subsistence shifting only in the context of major societal reorganisation (Verhart Reference Verhart2003). This phase features the manufacture of transitional forms of material culture, with the flow of ideas moving in both directions.

The Homogenisation phase begins roughly when the dual presence of foraging and farming has shifted decisively in favour of the latter. There is a progressive decline in the exploitation of wild resources, an increase in the role of domestic species, deforestation and the appearance of new cultural practices, including the building of large-scale monuments. It is only now that the transition to a Neolithic way of life is complete. Given the evidence of continuity and discontinuity (Figure 7), we suggest that this phase probably started by c. 3700 BC and no later than c. 3500 BC.

Discussion

The strength of our model is its ability to accommodate the contradictory evidence for continuity and change at the heart of contention over the origins of agriculture in Southern Scandinavia. It negates what are almost certainly simplistic explanations and allows for a degree of regional variation. At its core is recognition that the Neolithic Transition was a process that varied across time and space, and hence it can better accommodate and explain the geographic variability in evidence documented in the centuries after 4000 BC. Our model does not replace the three-phase model of Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy (Reference Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy1984), but instead applies it repeatedly across time. The hunting stations are evidence of groups in the Substitution phase (Zvelebil & Rowley-Conwy Reference Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy1984), while the contemporaneous settlement sites represent either groups already in the Consolidation phase, or incoming farmers. To emphasise this, the percentages of wild vs domestic species in the faunal assemblages from hunting stations contexts (Table S2) fit nicely into the ethnographic societies described by Rowley-Conwy (Reference Rowley-Conwy2004: fig. 7b) as undertaking the Substitution phase.

We argue that it may be impossible to define and match distinct material cultures to incoming farmers, the last foragers and groups intermediate to the two. Due to the strong possibility of inter-marriage and the associated transfer of skills, styles and traditions, any simple link between people and pots is meaningless. New forms of material culture and practice, however, are present from the outset, and are concurrent with the persistence of, or similarities with, earlier forms (Figure 7). From this, we surmise that during the Negotiation phase, the demographic balance between incoming farmers and the last foragers was relatively equal. Several lines of evidence support this assertion. Firstly, widespread forest clearance is rare before the Standardisation phase, which is an argument against large-scale immigration (Gron & Rowley-Conwy Reference Gron and Rowley-Conwy2017). Secondly, cattle were moved (Gron et al. Reference Gron, Montgomery, Nielsen, Nowell, Peterkin, Sørensen and Rowley-Conwy2016), possibly to maintain the breeding viability of very small herds at scattered frontier farms. Despite a general lack of MNI (minimum number of individuals) determinations, even the largest faunal assemblages are unlikely to represent more than a dozen or so animals—below the threshold of long-term herd viability (Bogucki Reference Bogucki1988). Perhaps most telling is the lack of large investment in communal construction during the Negotiation phase: there are no causewayed enclosures, despite the existence of such large-scale monuments in the regions from which the immigrants probably originated (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). There were not enough farmers to build them.

Conclusions

There is a need to shift the theoretical focus from top-down discussions of how agriculture came to Scandinavia to instead on how farming practices were actually transferred between societies. How did agriculture come to this region and why did it take time? The example of Southern Scandinavia demonstrates that the Neolithic Transition was dictated by a combination of factors, including demography, biogeography, subsistence and cultural practices. While each individual European Neolithic Transition occurred within its own unique setting, our model is probably applicable whenever indigenous foragers—in the face of incoming migrants—were able to maintain their traditional subsistence strategy for any length of time. As such, we suggest that the data indicate a period of economic and probable cultural negotiation, during which agriculture came to Scandinavia. Recent research has allowed a more nuanced understanding of agricultural origins by investigating, at a much finer scale, the timing and complexity of economic and cultural change during the earliest years of the Neolithic. Our approach does not require us to choose between migrationism, indigenism or integrationism, but instead looks to a combination of these, played out over time, indicating a process of economic, and probable cultural, dualism in the earliest centuries of the Funnel Beaker Culture. Our model is imperfect, but it is consistent with the existing data and flexible enough that it might incorporate new evidence in the future.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.71

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous colleagues for their thoughtful comments. K.J.G. and L.S. thank the Leverhulme Trust and the Carlsberg Foundation, respectively, for funding.