Introduction

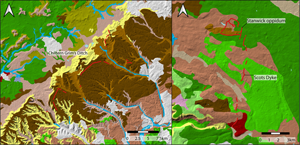

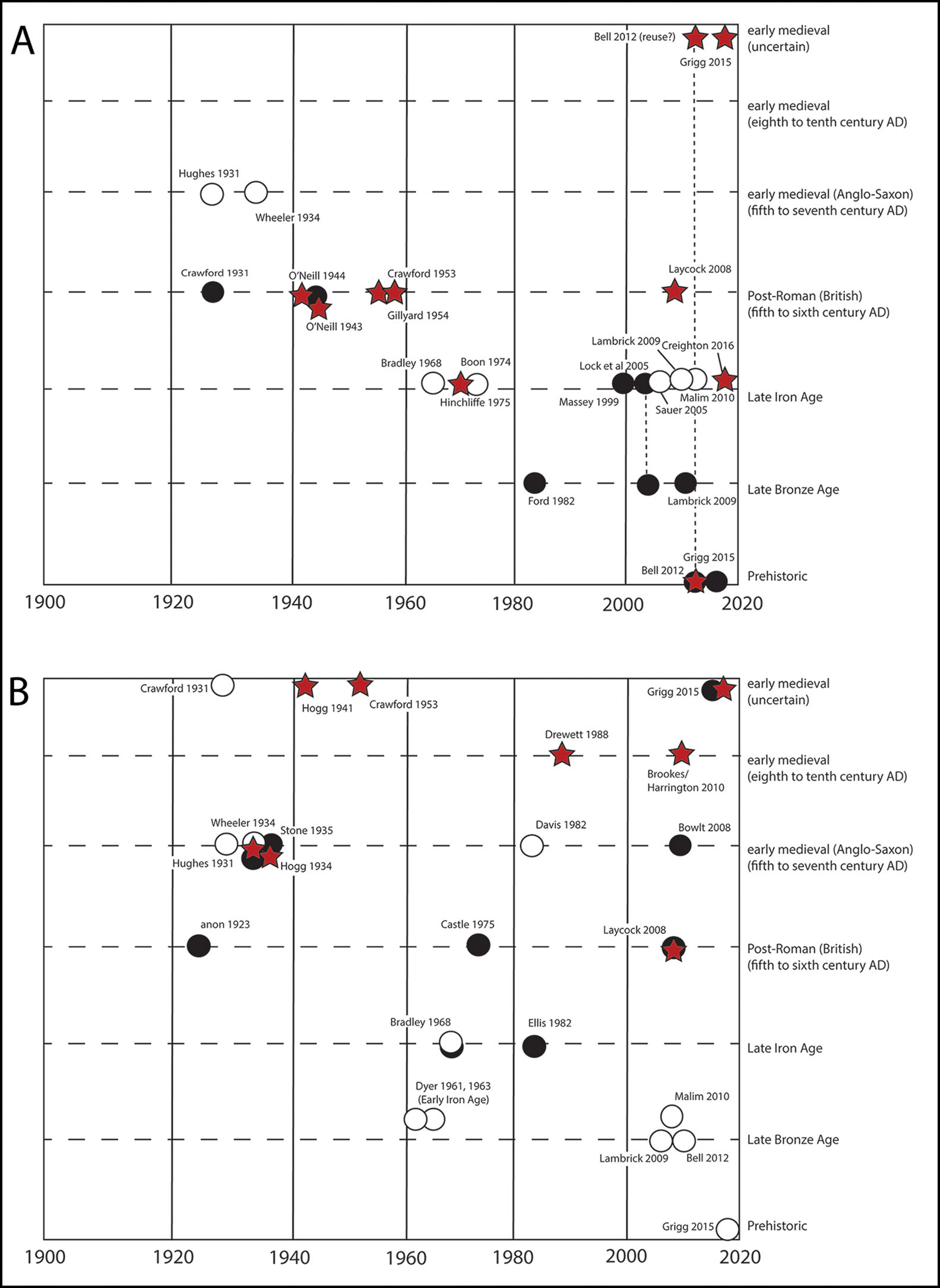

Monumental linear earthworks, or dykes, are found across the world inscribing the landscape, defining communities and channelling movement (Crawford Reference Crawford1953; Spring Reference Spring2015). In Britain, there are around 700 such earthworks, most surviving as upstanding features, but others only identifiable from aerial photography, geophysical survey and lidar imagery. While the dating of most is poor, current evidence points to increased rates of construction in the first millennium BC and mid-first millennium AD (Bell Reference Bell2012; Grigg Reference Grigg2015; Garland et al. Reference Garland, Harris, Moore and Reynolds2021; Figure 1). The physicality and significance of these earthworks have largely been explored in period or monument-specific studies. As the largest field monuments in Britain, linear earthworks provide significant opportunities to explore relationships between construction and social organisation and to compare the conceptual frameworks of distinct scholarly traditions.

Figure 1. Distribution of monumental linear earthworks in Britain as identified by the ‘Monumentality and Landscape: Linear Earthworks in Britain’ project (figure created by Nicky Garland).

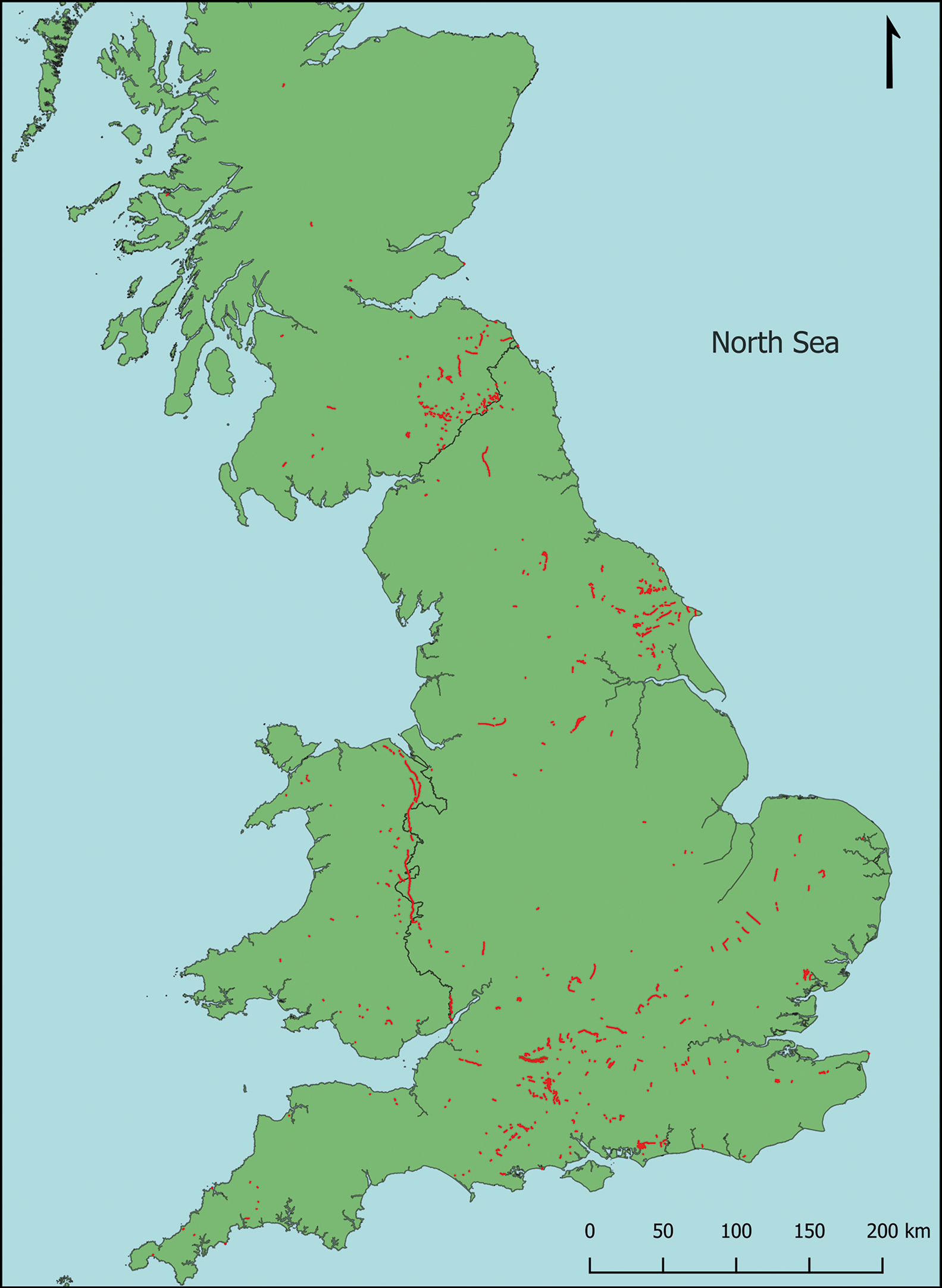

In Britain, land division increased significantly during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1600–1200 BC) taking various forms, from pit alignments to banks and ditches. Following the Middle Bronze Age, monumental linear earthworks appear to have been created in three main periods. During the Late Bronze Age (c. 1200–800 BC), linears marked a realignment of the landscape away from co-axial field systems (McOmish et al. Reference McOmish, Field and Brown2002; Yates Reference Yates2007); a second period of activity, although less widespread, during the Late Iron Age (first century BC–first century AD) saw earthworks in southern Britain used to define areas of landscape and ‘territorial oppida’ (e.g. Moore Reference Moore2012; McOmish & Hayden Reference McOmish and Hayden2015), with roughly contemporaneous earthworks constructed in Scotland (Barber Reference Barber1999: 138) and Ireland (Ó’Drisceoil & Walsh Reference Ó’Drisceoil and Walsh2021). The third period of construction is the early medieval, traditionally related to the territorial claims of ‘British’ and ‘Anglo-Saxon’ communities in the fifth–sixth centuries AD or later, most famously, Offa's Dyke between English and Welsh kingdoms in the eighth century AD (Ray & Bapty Reference Ray and Bapty2016). Within this corpus, certain monuments, such as Wansdyke in Wiltshire (Figure 2) and Scots Dike in North Yorkshire, are of a scale that invite special attention, and which are the focus of the following discussion.

Figure 2. The Roman Road and Wansdyke above Calston, 20 May 1724 (from Stukeley Reference Stukeley1743: 18, table 10).

Crawford's legacy

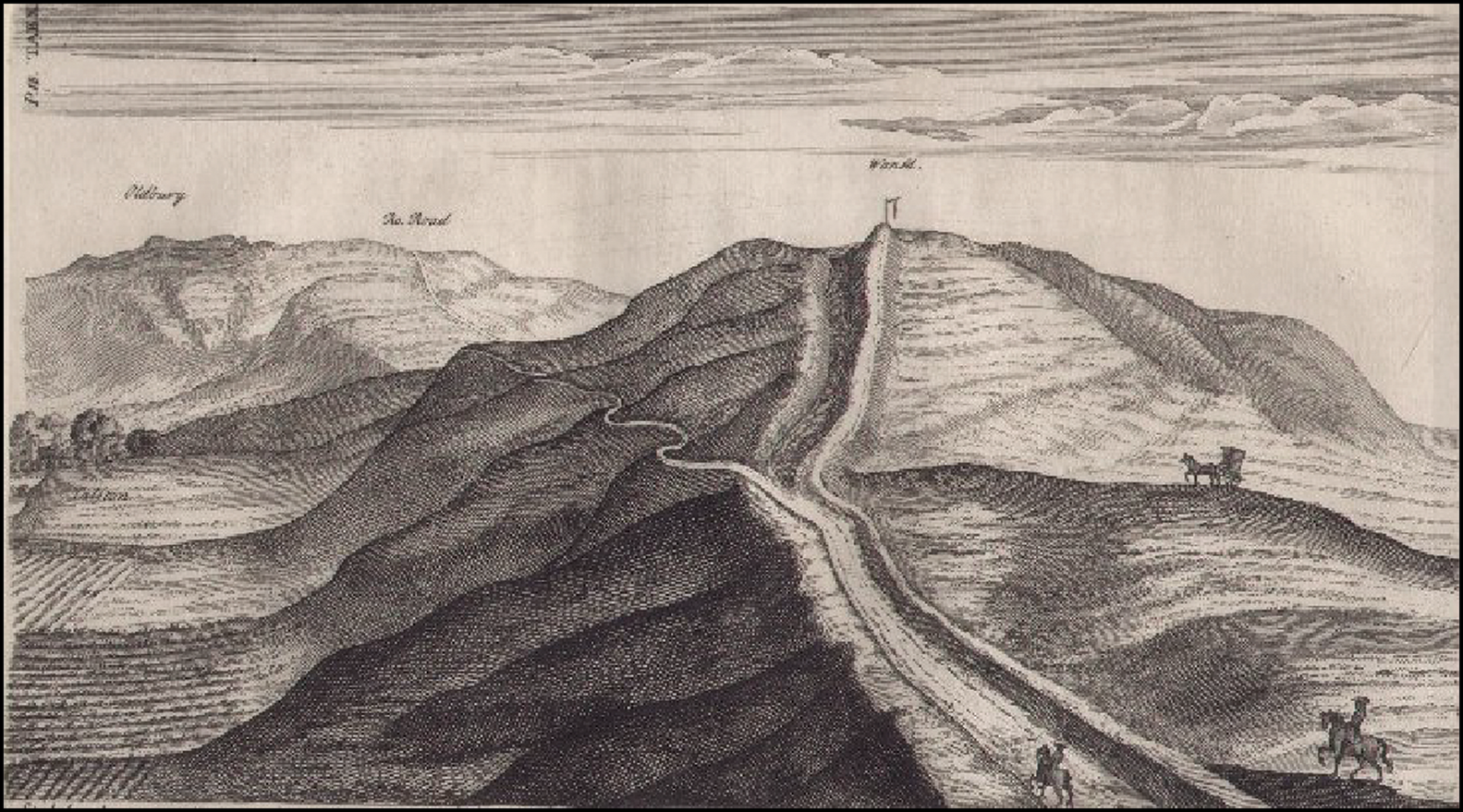

It is apt to re-examine these monuments in the pages of Antiquity, for it was O.G.S. Crawford, its founding editor, and therefore by extension the journal, that shaped the perspectives on linear earthworks that dominated their interpretation for much of the twentieth century and which still reverberate today. Starting with Cyril Fox's seminal 1929 study, through to the 1950s, Antiquity published 29 articles on dykes (Figure 3). Crawford used the journal to promote research on linear earthworks, arguing they had been poorly served by previous scholarship yet were fundamental to narratives of past societies (Crawford Reference Crawford1931, Reference Crawford1953; Bowden Reference Bowden2001: 36). This view was espoused most eloquently by Fox (Reference Fox1929: 148):

When one considers how exhaustive an effort was involved in the[ir] construction … and how profoundly their presence … influenced the economic, military, and political development of the communities whose boundaries they formed, one can realize how important it is … to determine the period of their construction and use.

Figure 3. Graph showing research papers and book reviews focused on linear earthworks (dykes) in the journal Antiquity (prepared by Tom Moore).

By the late twentieth century, interest in dykes had declined generally (Reynolds Reference Reynolds, Gilchrist and Reynolds2009: 413) and discussion of them largely disappeared from Antiquity (Figure 3). While the twenty-first century has seen something of a research revival (Bell Reference Bell2012; Ray & Bapty Reference Ray and Bapty2016; Williams & Delaney Reference Williams and Delaney2019), dykes remain largely the preserve of early medieval studies (e.g. Grigg Reference Grigg2015, Reference Grigg2018); marginalised from mainstream archaeology (Bell Reference Bell2020: 32), their significance is often overlooked in diachronic landscape studies (e.g. Gosden et al. Reference Gosden2021). As British archaeology has become data heavy, with specialists working on specific periods, often with markedly different theoretical perspectives, comparative approaches have become less common. Here, we examine the basis of this divergence in interpretation, arguing that comparative approaches to earthworks of different dates have the potential to provide new understandings of these monuments.

Chronological constructs

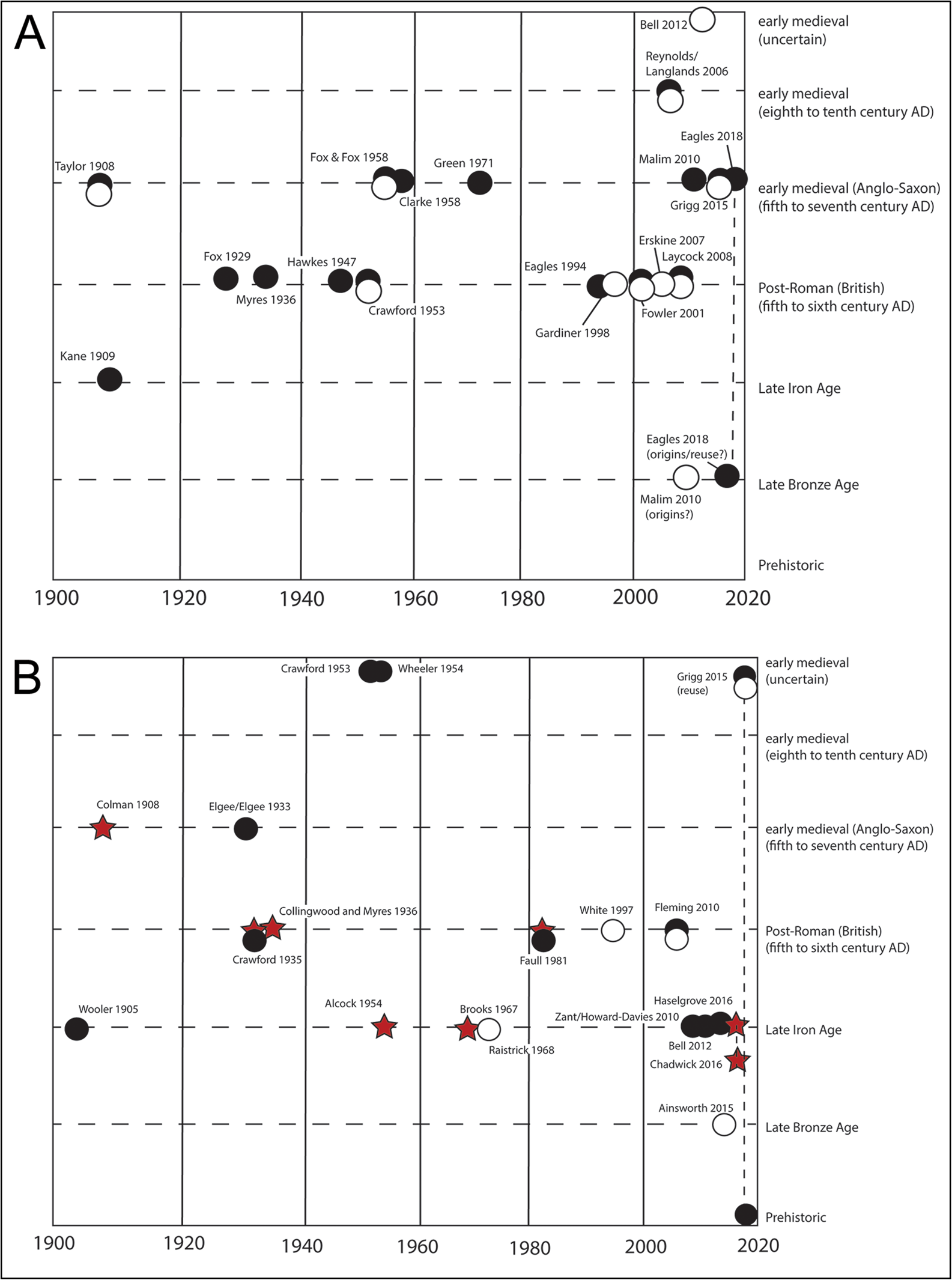

A key challenge in the study of linear earthworks concerns dating. Although new archaeometrical methods can provide high-resolution dates, few linears have currently been subject to such techniques (Garland et al. Reference Garland, Harris, Moore and Reynolds2021) and have often been ascribed to particular periods solely on the basis of scholarly traditions. Examples of some well-studied earthworks illustrate how the dates attributed to monuments have changed over time with the shifting interpretative trends in British archaeology (Figures 4 & 5). In early twentieth-century studies, the majority were ascribed to the post-Roman period (Fox Reference Fox1929: 150; Crawford Reference Crawford1953: 184), reflecting uncertain dating, but also their appropriation for select period narratives. This early medieval dating was driven by the idea that archaeological evidence could be interpreted by uncritical reference to the written sources (e.g. Randall Reference Randall1934; Collingwood & Myres Reference Collingwood and Myres1936: 320). Textual evidence connecting Offa's Dyke to the eighth-century AD eponymous king (Fox Reference Fox1929: 140), for example, led to other monuments being related to historical events recounted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and other sources (Hughes Reference Hughes1931; Fox & Fox Reference Fox and Fox1958). In turn, earthworks lacking any apparent historical attestation were assumed to share similar, yet undocumented, events (Fox Reference Fox1929: 150), with a tendency to relate dykes to post-Roman ‘British’ territories, rather than later Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (Reynolds & Langlands Reference Reynolds, Langlands, Davies, Halsall and Reynolds2006), such examples are the Berkshire Grim's Ditch and the Yorkshire dykes (Figures 4 & 5). The desire to create quasi-historical narratives of post-Roman kingdoms and to chart the conquests described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Wheeler Reference Wheeler1934a) reflected a naïve approach to the written sources that persisted into the 1970s (e.g. Dumville Reference Dumville, Sawyer and Wood1977); it also resonated with early twentieth-century theories regarding migration as the agent of social change (Leeds Reference Leeds1913).

Figure 4. Graphs showing dates that authors ascribed to particular linear earthworks, by year of publication. A) Grim's Ditch, Berkshire (black circle); Padworth Grim's bank, Berkshire (red star); and South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch (white circle); B) Pinner Grim's Ditch, Middlesex (black circle); Chiltern Grim's ditches (white circle); and Faesten dic, Kent (red star) (figure prepared by Tom Moore).

Figure 5. Graphs showing dates that authors ascribed to particular linear earthworks, by year of publication. A) East Wansdyke (black circle); and West Wansdyke (white circle); B) Scots Dike, North Yorkshire (black circle); Aberford Becca bank (red star); and Fremington dykes (white circle) (figure prepared by Tom Moore).

By the mid-twentieth century, archaeological research had established that some less monumental earthworks were of Late Bronze or Early Iron Age date (Hawkes Reference Hawkes1940; Piggott Reference Piggott1944; Figure 4). This discovery prompted the realisation that certain monumental examples, such as the Berkshire and Chiltern Grim's Ditches, might also be prehistoric (Dyer Reference Dyer1961; Ford Reference Ford1982). This was both a dating and wider conceptual revolution, coinciding with the recognition of complex Bronze and Iron Age land-division (Bowen & Fowler Reference Bowen and Fowler1978; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Entwistle and Raymond1994). This trend towards the identification of earlier dates continues today; despite arguments that the Swaledale dykes in Yorkshire are early medieval (Fleming Reference Fleming2010), for example, a more recent convincing study dates them to the Late Bronze Age (Ainsworth et al. Reference Ainsworth, Gates and Oswald2015). For a few monuments, such as Wansdyke and Faesten dic, however, recent studies have proposed a later (Anglo-Saxon) date (Reynolds & Langlands Reference Reynolds, Langlands, Davies, Halsall and Reynolds2006; Doyle White Reference Doyle White2020; Figure 5).

Despite the successful application of radiocarbon dating to a number of linear earthworks (Garland et al. Reference Garland, Harris, Moore and Reynolds2021), some scholars, promoting select historical narratives, persist with the default assumption of an early medieval date. Grigg (Reference Grigg2015), for example, proposes 103 dykes as ‘probably’ or ‘possibly’ early medieval, with only 18 probably prehistoric or Roman. Laycock (Reference Laycock2008) similarly views most linear earthworks as built by ‘re-emerging’ British ‘tribes’ in the fifth century AD (Figures 4 & 5). Consequently, many (undated) dykes continue to be assigned to a ‘sub-Roman’ period, without clear justification or connection to the social and cultural developments of early medieval Britain.

In reassessing these monuments, it is also important to recognise their long biographies, in some cases extending from later prehistory to the present. Excavation of several examples reveals that early medieval earthworks recut or followed the alignment of earlier, sometimes less monumental, linear features. This appears to be the case for some of the Cambridgeshire dykes, which follow the course of Iron Age ditches (Mortimer Reference Mortimer2017), while Bokerley Dyke (Bowen Reference Bowen1990: 40) and Wansdyke (Eagles Reference Eagles2018: 99) may have incorporated Late Bronze Age earthworks. Other examples reveal how linear earthworks continued to inform the use of, and movement through, the landscape. The Huggate dykes in East Yorkshire changed functions from a Late Bronze Age boundary to a Late Iron Age routeway, and then a medieval green lane (Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2021: 74). This was not simply a succession of uses, but a continuum of interaction between the experiences and memories of individuals and communities, of human, animal and natural forces (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2016b: 267).

Interpretative straitjackets

As the dates ascribed to these monuments have changed, so too have their interpretations. Until the later twentieth century, discussion focused on defensive functions. Whether assumed to be pre- or post-Roman, Scots Dike in North Yorkshire, for example, was suggested to represent a response to an eastern threat (e.g. Wooler Reference Wooler1905; Fleming Reference Fleming2010). Such ideas rested on the notion that the builders controlled the territory on the bank side, and that many dykes obstructed routeways inhibiting the movement of armies (Grigg Reference Grigg2015: 211); rare examples of weapons and burials located within dykes have been viewed as evidence of battles (e.g. Lethbridge Reference Lethbridge1958). Another proposed function is the prevention of cattle rustling, slowing down stolen herds and enabling raiding parties to be intercepted (Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2016: 325).

With the recognition that some earthworks dated to the later prehistoric period, interpretations shifted. Crawford (Reference Crawford1953) distinguished between prehistoric agricultural linears and post-Roman defensive earthworks. Berkshire Grim's Ditch, for example, had been considered to be a ‘British’ defensive structure against the Anglo-Saxons (O'Neil Reference O'Neil1944) but, when re-dated to the Late Bronze Age, was reinterpreted as defining farming territories (Ford Reference Ford1982). Indeed, assessment of the topographical location of some earthworks suggests that many were poorly placed for defence, as is clear from examples in East Yorkshire (Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2016).

The decline during the later twentieth century in the emphasis on defence reflected a more general downplaying of warfare in later prehistory (James Reference James, Haselgrove and Pope2007). Challenging this ‘pacification’, the significance of conflict has recently been revived in relation to the interpretation of certain Iron Age earthworks, for example at Chichester, as a deterrent against attacking chariots (Magilton Reference Magilton and Wilson2003: 159). Despite some nuance of interpretation (e.g. Malim Reference Malim2010: 250; Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2016), however, the dominant trend continues to see prehistoric linears as marking tenure and rarely serving any martial role (McOmish et al. Reference McOmish, Field and Brown2002: 64; Fenton-Thomas Reference Fenton-Thomas2003). In contrast, within early medieval studies, martial interpretations remain prevalent (Grigg Reference Grigg2015, Reference Grigg2018), despite some emerging attempts to incorporate social and symbolic roles (Squatriti Reference Squatriti2002; Williams Reference Williams2021). This interpretative divergence largely rests on the contrasting models of social organisation that are seen to define these periods: smaller, more heterarchical communities of the early first millennium BC versus more hierarchical Late Iron Age and early medieval societies. There is also a division within early medieval studies between those scholars who work on the smaller-scale martial societies of the fifth and sixth centuries AD and those who deal with the state-level societies of the eighth and ninth centuries (Gilchrist & Reynolds Reference Gilchrist and Reynolds2009).

The defensive interpretation of dykes has also been closely connected to the suggestion that they were expressions of social identity. For Wheeler (Reference Wheeler1934b: 446) linears were an “obvious expression of territorial adjustment in an illiterate age”. This perspective, shared at the time by early medievalists and prehistorians, emerged in an intellectual climate where cultural entities could be directly mapped onto the landscape: if Offa's Dyke delimited the borders of Mercia, so all dykes were assumed to define ethnic or political groups. Thus, the Chiltern Grim's Ditch was regarded by Hughes (Reference Hughes1931) as defining the West Saxons, while Bradley (Reference Bradley1968: 13) saw it as the limits of the Iron Age Belgae. Regarding dykes as spatially defining cultural groups or polities encouraged narratives that assumed chronological coherence among these linear earthworks; Wheeler (Reference Wheeler1934a), for instance, used various dykes, almost certainly of different origins, to argue for the existence of a post-Roman ‘British’ polity around London.

Despite subsequent theoretical revolutions, the dominant interpretation today remains that linear earthworks were socio-cultural barriers. Rippon (Reference Rippon2018: 326), building on earlier observations (Hart Reference Hart1992), regards the Cambridgeshire dykes as a fluctuating border between the Middle Saxons and the kingdom of East Anglia, and as a means of controlling the principal routes into the latter. Similar assertions have been made for Aves Ditch in Oxfordshire, North Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch and South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch as the territorial delimitations of Late Iron Age ‘tribes’ (Sauer Reference Sauer2005: fig. 28; Lambrick et al. Reference Lambrick, Robinson and Allen2009: 70).

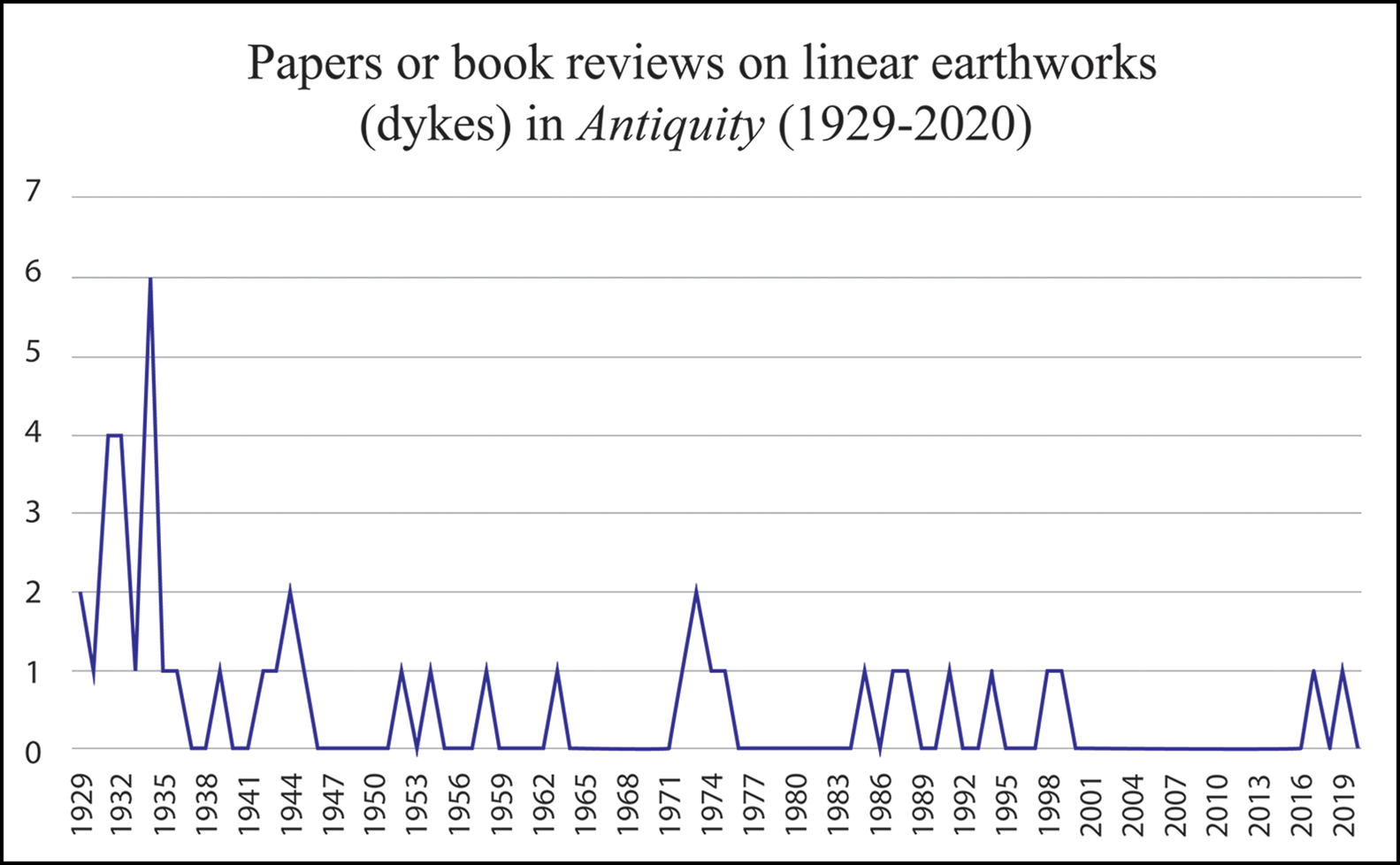

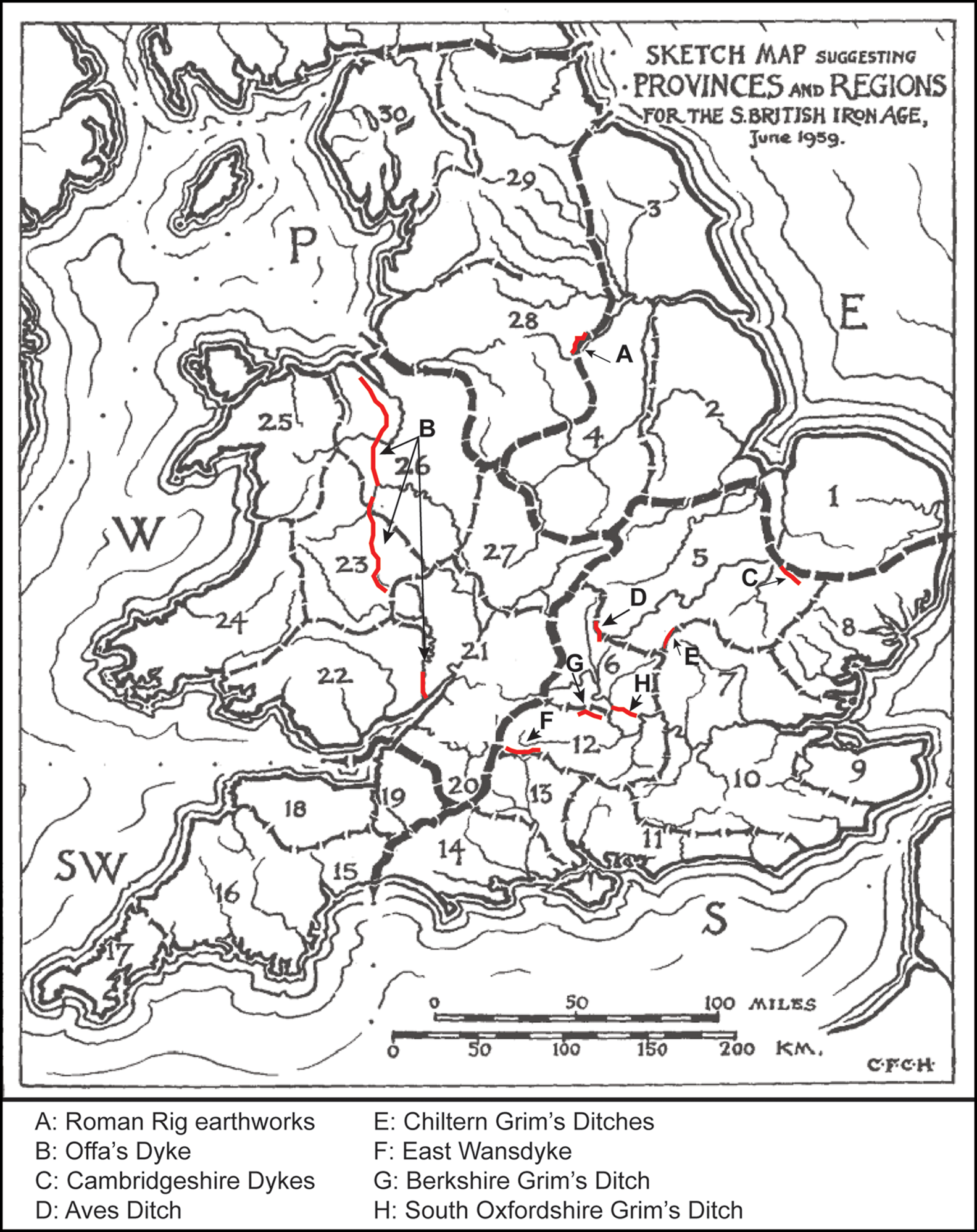

In viewing linears as cultural boundaries, scholars often make little distinction between ethnic and political communities. This is particularly evident when arguing that linears reflected long-term regional identities. For example, the nexus of South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch and Berkshire Grim's Ditch has been regarded as an Iron Age frontier zone, which re-emerged in the post-Roman period (Malim Reference Malim2010: 166). Such ideas are not new. Fox (Reference Fox1929: 152) suggested that the Cambridgeshire dykes, although demonstrably early medieval, reanimated the earlier border between the Iron Age Iceni and Catuvellauni. This echoed what Hawkes (Reference Hawkes1959) described as the cultural divisions of Iron Age Britain (Figure 6). Although Hawkes omitted linear earthworks from his article, it seems more than coincidence that many dykes coincide with the limits of his ‘regions’ and ‘provinces’. Thus, supposedly ‘natural’ cultural divisions became embedded in perspectives of the day and remain surprisingly persistent. Underpinning this is a problematic notion—that Roman Britain was a veneer covering Iron Age society, subsequently wiped away in the post-Roman period to reveal stable underlying identities, which were reasserted through linears. In practice, the Roman period instigated the complex transformations of identities (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2004). The suggestion that late or post-Roman dykes marked the (re)emergence of conflict between pre-existing ethnic groups (Laycock Reference Laycock2008; Eagles Reference Eagles2018) is therefore hard to sustain, relying as it does on unfeasibly static cultural identities (Moore Reference Moore2011).

Figure 6. Map showing how C.F.C. Hawkes's provinces and regions relate to major linear earthworks (shown in red) (redrawn by Tom Moore after Hawkes Reference Hawkes1959).

A comparative approach

Our historiographical approach reveals linear earthworks to be at the forefront of a dialogue between later prehistoric and early medieval studies yet confounded by contrasting conceptual approaches. How might cross-period dialogue lead to more robust interpretations of these monuments? Is it intellectually sustainable to pursue divergent explanatory narratives in later prehistoric and early medieval archaeology? Following critiques of social evolutionary perspectives and ethnographic generalisations (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2007), in recent years, comparative archaeology has revived (Cipolla & Howlett Hayes Reference Cipolla and Hayes2015; Gyucha Reference Gyucha2019). While various approaches exist (Smith & Peregrine Reference Smith, Peregrine and Smith2012), rather than defining societies as analogous we emphasise the benefits of comparison through the re-evaluation of conceptual frameworks, reflecting on the role of monuments in their social contexts.

Two eras in which linear earthworks were constructed stand out as worthy of reflective comparison: the Late Iron Age and early medieval periods. Dialogue between archaeologists specialising on these periods is uncommon despite the comparisons that can be made (Reynolds Reference Reynolds, Gilchrist and Reynolds2009: 412). This is partly due to inadequacies in approaches which emphasised ‘Celtic’ cultural continuity and feudal models based on problematic textual evidence (Collis Reference Collis2003), leading Anglophone prehistorians largely to reject early medieval analogies (Moore & Armada Reference Moore, Armada, Moore and Armada2011: 32); this contrasts with Scandinavian and Irish approaches where comparisons are more commonly made (Hedeager Reference Hedeager2011; Gleeson Reference Gleeson2021).

Nonetheless, Late Iron Age and early medieval societies in Britain do share similar traits, in terms of material culture (e.g. coinage), scales of social organisation and, potentially, in the articulation of power (cf. Semple et al. Reference Semple, Sanmark, Iversen, Mehler, Hobæk, Ødegaard and Skinner2020; Moore & Fernández-Götz Reference Moore and Fernández-Götz2022). The following sections highlight two areas where dialogue may challenge assumptions about linear earthworks within periods of similar social complexity.

Boundaries and polities

Linear earthworks offer great potential regarding the scale and boundedness of social groups. Can we assume both Aves Ditch, in the Late Iron Age, and Wansdyke, in the early medieval period, defined bounded polities? Rather than static cultural entities, discussions of both the Late Iron Age (Hill Reference Hill, Moore and Armada2011) and early Middle Ages (Brookes & Reynolds Reference Brookes, Reynolds, Escalona Monge, Vésteinsson and Brookes2019; Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Reynolds and Yorke2019) emphasise temporally and spatially fluid forms of power. Coinage, burial rites and material culture suggest a less fixed hierarchy and instead greater connections through clientage and kinship (Creighton Reference Creighton2000; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2019) enacted at assemblies (Semple et al. Reference Semple, Sanmark, Iversen, Mehler, Hobæk, Ødegaard and Skinner2020). Both periods, however, also bore witness to social coalescence, often framed as state or kingdom formation, rendering monumental linear earthworks as potential reflections of large-scale political formations.

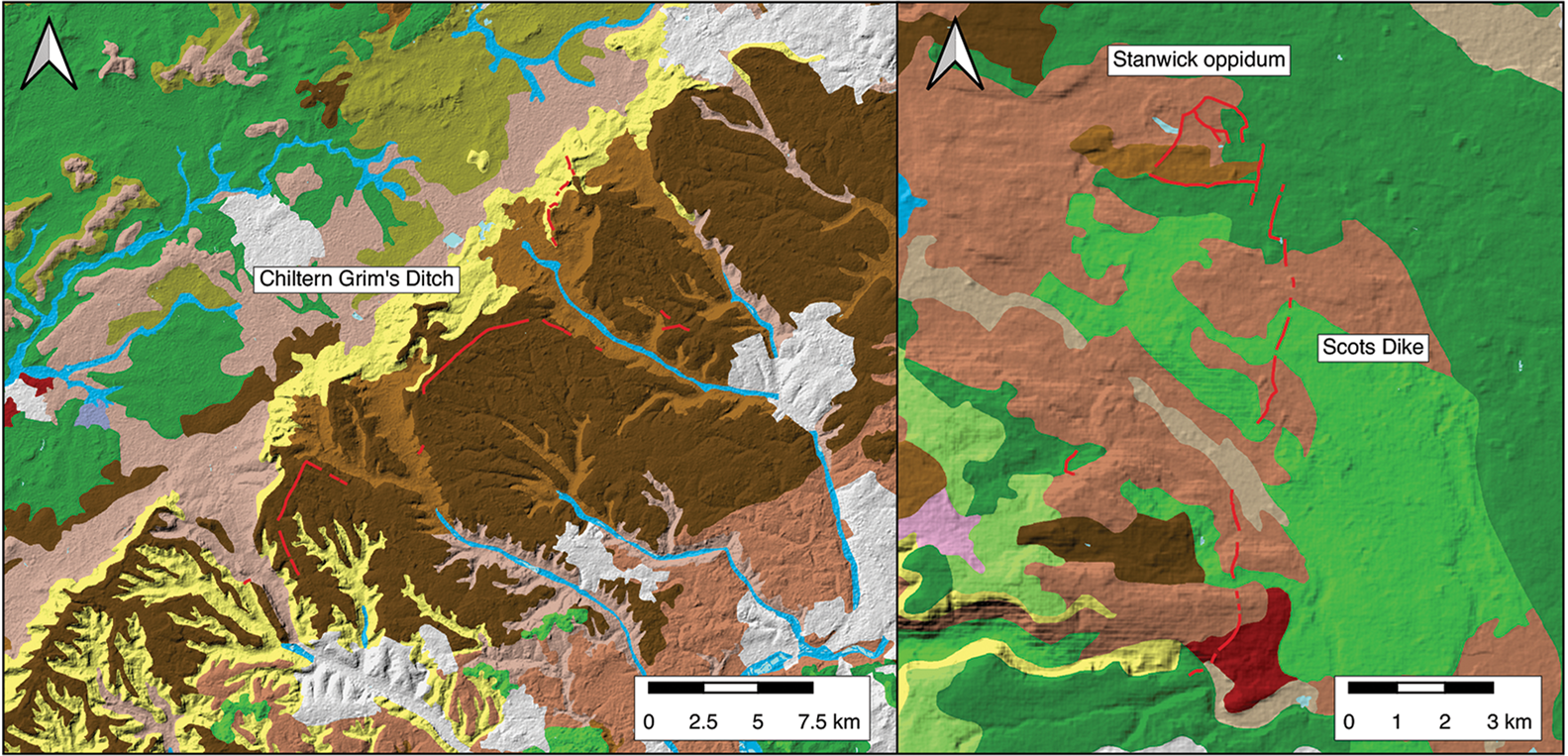

Current social reconstructions of both periods sit uneasily with the idea that earthworks were fixed cultural boundaries, but they remain products of, and shaped, the social landscape. Early medieval perspectives may be useful here for reflecting on the role of Iron Age boundaries. Offa's Dyke was not simply a border, but a landscape marker of different rules, obligations and meanings (Ray & Bapty Reference Ray and Bapty2016). Earthworks thus defined social space, rather than people, dictating movement and access through and between landscapes (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2016a, Reference Chadwickb). Certain linear earthworks clearly defined different landscape types. The Chiltern Grim's Ditches, for example, delimited areas of different soil types (Figure 7); cultural-historical narratives regarded this as evidence of groups practising different farming techniques (Wheeler Reference Wheeler1934a: plate 25; Bradley Reference Bradley1968: 12). It seems more likely, however, that this marked differences in agricultural practices related to social conditions—perhaps areas for hunting or stock grazing—rather than cultural identity.

Figure 7. Map of Chiltern Grim's Ditch and Scots Dike against soil classifications (defined by Cranfield's Soilscapes project: https://www.landis.org.uk/soilsguide/soilscapes_list.cfm) (prepared by Barney Harris).

This link with social and economic organisation may explain the presence of linear boundaries within polities identifiable from other sources (e.g. coinage or texts), such as the possibly Iron Age Scots Dike in the region of the Brigantes, or Chichester dykes in the area of the Atrebates. We might draw inferences here from Late Bronze Age linears, for example in East Yorkshire, and many Iron Age examples too, which appear to have been created not to define ‘them and us’, but instead to regulate movement, especially of livestock, between landscapes (Fenton-Thomas Reference Fenton-Thomas2003; Chadwick Reference Chadwick2016a, Reference Chadwickb; Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2016). This emphasises that scale need not equate with function; Crawford (Reference Crawford1953: 183) recognised that medieval park boundaries could be substantial not just for functionality but as symbols of power, defining landscapes through social constraints (Mileson Reference Mileson2009).

Conversely, earthworks could define tenure. Charter evidence suggests the Fullinga dic in Middlesex, for example, defined the territory of a seventh-century petty-chief and an otherwise unknown people (Doyle White Reference Doyle White2020). Some linears found within later polities may have once formed limits to smaller polities. But even where substantial earthworks such as Wansdyke marked a boundary between large-scale polities (Mercians and West Saxons), its relationship to local boundaries (of hundreds and parishes) seemingly shows, in a local context, that it did not structure or influence patterns of community identity. In the case of East Wansdyke, there is evidence that the earthwork bisected an earlier polity, then became a major boundary and then a relict feature sitting within a later territorial entity, which is now Wiltshire (Reynolds Reference Reynolds, Brown, Field and McOmish2005). It is only possible to reconstruct this trajectory because of a wide range of sources, including documents, placenames, historical geography and archaeology. To what extent Iron Age boundaries had similar biographies is harder to determine. The nexus of boundaries around South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch, for example, maps onto an area of overlap between different Late Iron Age coin distributions, potentially reflective of separate polities (Sauer Reference Sauer2005; Figure 8). Other textual evidence, however, such as Cassius Dio's indication of a division in the ancient British Dobunni, alongside complexity in the coin evidence when mapped by the individuals named on them, implies a more fluid socio-political environment (Moore Reference Moore2011; Figure 9). Nevertheless, the correspondence of a range of earthworks within a zone of interaction between Iron Age groups may imply they were manifestations of nascent polities or sometimes short-term political situations. In these ways, the two periods share similarities of trajectory and multiple scales of territoriality visible in the linear earthworks.

Figure 8. Comparison of the distribution of Iron Age coins in relation to the linear earthworks at South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch, North Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch and Aves Ditch by so-called ‘Tribe’ denomination (image produced by Barney Harris).

Figure 9. Comparison of the distribution of Iron Age coins in relation to the linear earthworks at South Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch, North Oxfordshire Grim's Ditch and Aves Ditch by so-called ‘Tribe’ denomination by select named individuals on Iron Age coins (images produced by Barney Harris).

Linear earthworks and power

While linears may not have always defined cultural boundaries, it seems more than a coincidence that a spate of construction took place when larger social entities were emerging. The high labour demand required for earthwork construction is well recognised as requiring increasing social obligations and organisational capacity (Grigg Reference Grigg2015; Garland Reference Garland2016; Harris Reference Harris2020; Moore Reference Moore2020). Many early medieval scholars therefore consider linears more as a physical statement of power than for defence (Squatriti Reference Squatriti2002: 334; Reynolds & Langlands Reference Reynolds, Langlands, Davies, Halsall and Reynolds2006: 31–4). Their practical effectiveness may have been less fundamental than their expression of labour and power over large areas, at a time when the social reach between elites and others was growing. This may help to explain the immense scale and over-elaboration of many earthworks, such as the multiple banks and ditches at Huggate in East Yorkshire (Fioccoprile Reference Fioccoprile2016), and the elaborate entrance structures found on East Wansdyke (Reynolds & Langlands Reference Reynolds, Langlands, Davies, Halsall and Reynolds2006), both representing a “multiplication of monumentality” (Giles Reference Giles2012: 42).

Early medieval studies tend to focus on earthworks as manifestations of the power of monarchs. Among later prehistorians, there has been considerable debate as to what extent earthworks, around henges or hillforts, reflect so-called ‘chiefdoms’ or more communal constructions affirming group identity (e.g. Hill Reference Hill, Champion and Collis1996; Fleming Reference Fleming, Cherry, Scarre and Shennan2004; Lock et al. Reference Lock, Gosden and Daly2005), although less so in relation to linear monuments (Moore Reference Moore2012). Either way, these monuments reflect the scale of social organisation and depend upon the balance between free will and coercion. Numerous proposals exist (e.g. Renfrew Reference Renfrew and Renfrew1973; Sharples Reference Sharples2010) but the mechanisms of labour mobilisation remain elusive; participants may have provided their labour willingly, perhaps being tied by obligations of kinship or clientage, or may have been enslaved or coerced. For both the Late Iron Age and early medieval era it seems likely that similar articulations of power existed around obligations of labour, some of which may have been intimately linked to seasonal agricultural practices (Garland Reference Garland2020), although the precise dynamic remains uncertain. Concepts of costly signalling may be relevant here (O'Driscoll Reference O'Driscoll2017), emphasising the desire of these communities, whether hierarchical or heterarchical, to pre-emptively construct a mental and physical deterrent and emphasise power through excessive labour consumption, particularly at times of changing social dynamics.

Whether labour was exacted by supra-local authorities or more freely provided, efforts seem likely to have been directed at internal, as well as external, communities (Lock et al. Reference Lock, Gosden and Daly2005: 134). Processes of construction were potentially crucial in both periods as larger social entities formed, ensuring smaller communities acted as part of a broader collective: meeting communities from afar, sharing food, and journeying to construction locations. All will have engendered group identity, with or without coercion. Prehistorians emphasise how the digging of earthworks, as well as movement along them, helped define communities’ relationships with their environment (Giles Reference Giles2012: 41). Certain linears seem to have been periodically refurbished (McOmish et al. Reference McOmish, Field and Brown2002: 58) with evidence from some of the Aberford Dykes, for example, of repeated social-symbolic acts reaffirming the importance of the boundary (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2016b: 258). The naming of certain earthworks after heroic ancestor/deities, most notably Offa's Dyke and Wansdyke, may similarly have served as mechanisms for embedding a sense of collective belonging through perceived lineage and folk origin (Reynolds & Langlands Reference Reynolds, Langlands, Davies, Halsall and Reynolds2006). The reuse of some linears through the interring of early medieval burials in prehistoric earthworks (e.g. Sauer Reference Sauer2005) also illustrates how, once in the landscape, earthwork biographies were moulded by later communities.

The building of an earthwork over landscapes divided by fields and routeways demands either agreement about its course by communities over a large area, or its imposition. Late Bronze Age linears bisecting earlier co-axial field systems are well documented (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2000). The placing of Late Iron Age and early medieval earthworks is less studied, although our initial observations from Scots Dike in North Yorkshire seem to indicate that it ignored existing field boundaries.

Can we conclude that Late Iron Age and early medieval linear earthworks were conceptually and functionally different from those of the Bronze Age, or is this constrained by our understandings of differing social complexity? The contrast seems to lie in the Bronze Age being part of a unified agricultural system (Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Entwistle and Raymond1994), whereas the Late Iron Age and early medieval linears appear focused on the social and political definition of landscape. The ways in which linears related to relationships between local tenure and higher-order undertakings is thus fundamental for future enquiry. Relationships between power, identity and earthworks invite us to reconsider conceptual distinctions between Late Bronze Age, Late Iron Age and early medieval societies, all of which required physical manifestations of territoriality.

Conclusions

Our assessment of the linear earthworks of Britain emphasises how, despite some excellent studies of individual linear earthworks (e.g. Ray & Bapty Reference Ray and Bapty2016; Williams Reference Williams2021), theoretical and material advances in their study remain constrained by period-based interpretative models little changed since the early twentieth century. Differences of interpretation relate not solely to materially different archaeologies, but to contrasting frameworks for interrogating landscape. The study of linear earthworks is a powerful lens through which to articulate dialogue about social complexity between early medievalists and prehistorians, focusing less on identifying societies with similar traits and interpreting them in the same ways, and more on challenging preconceptions of the roles of these monuments in different societies across time. To understand the biography of these monuments and their roles in reflecting and dictating landscapes of movement and experience, their study requires inter-disciplinary (including the use of historical texts), multi-period, landscape-scale analysis. Contemporary approaches offer the potential for such study. Developments in OSL and radiocarbon dating, alongside Bayesian analysis, provide the potential to establish more refined chronologies, teasing out the biographies of these earthworks. Similarly, advances in GIS and computer modelling allow for improved interrogation of the labour involved in the construction of linears and how they framed the movement of animals and people. The time is ripe, therefore, to revisit the challenge set down by Crawford and Antiquity's early contributors (Fox Reference Fox1929; Crawford Reference Crawford1953) of understanding the roles and routes of Britain's ‘dykes’.

Funding statement

This article is an output of the ‘Monumentality and Landscape: Linear Earthworks in Britain’ project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-209-359).