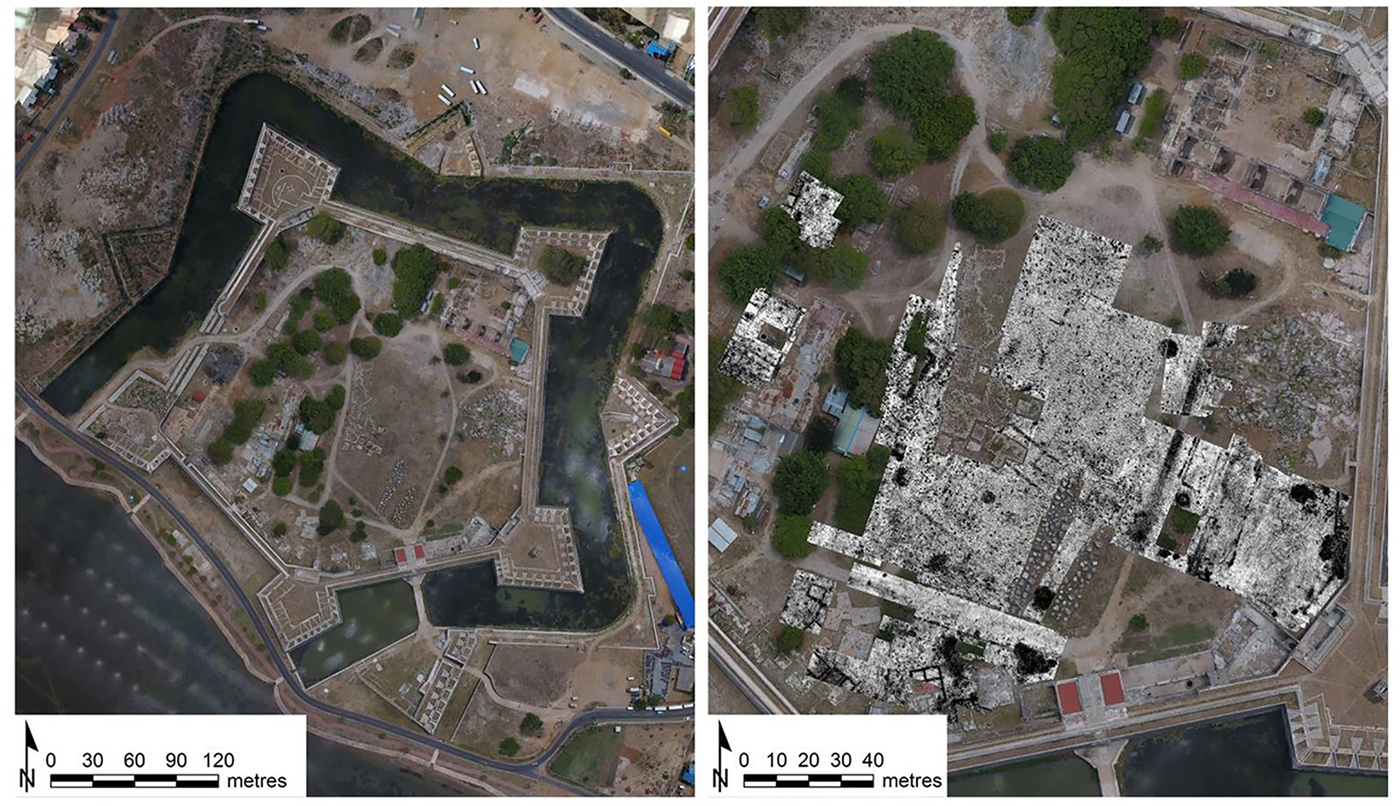

The Dutch East India Company besieged the Portuguese fort at Jaffna in March 1658. With terms of surrender agreed on 22 June 1658, they encountered a site “battered to pieces” (Baldaeus Reference Baldaeus1703: 798) and proceeded to level or remodel damaged structures. The outer works were completed in 1792, transforming the site from a quadrangle to a pentagonal fortification (Figure 1), but the poorly provisioned Dutch garrison surrendered to British forces three years later without firing a shot (Nelson Reference Nelson1984: 82–83). More recently, Jaffna Fort was a strategic and symbolic focus during the conflict between the Sri Lankan Government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam—a humanitarian catastrophe that also destroyed cultural heritage.

Figure 1. UAV image of Jaffna Fort, looking west.

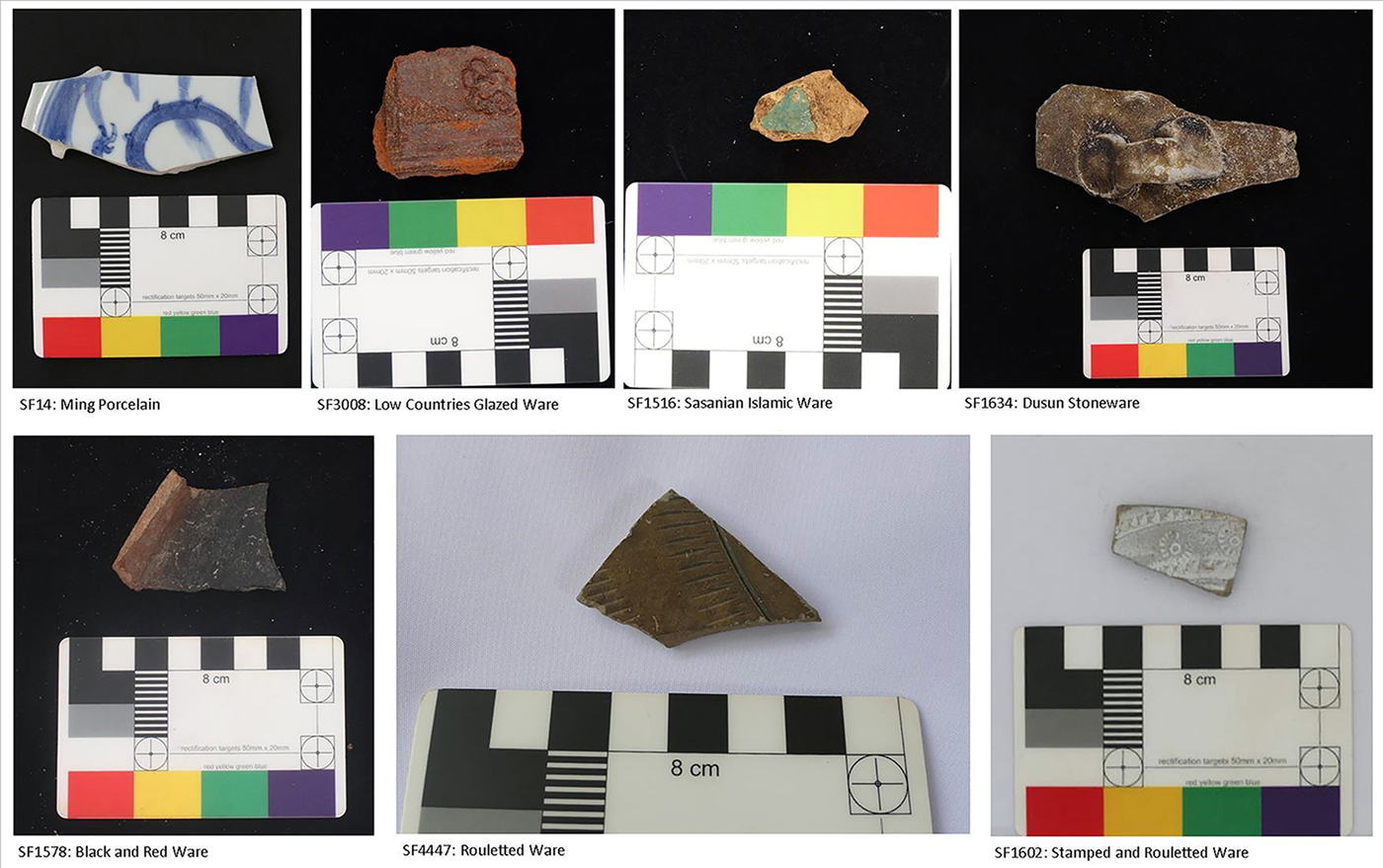

This heritage is now a focus for efforts to address reconciliation, renewal and peacebuilding through tourism and its associated economic impacts (Pushparatnam Reference Pushparatnam2014). Conservation to date has concentrated on colonial-era structures (Mudiyanselage Reference Mudiyanselage, Lambert and Rockwell2011). Recent discoveries uncovered during the construction of new visitor infrastructure, however, including Rouletted Ware (c. 200 BC–AD 200) (Tomber Reference Tomber2000; Ford et al. Reference Ford, Pollard, Coningham and Stern2005) and ceramics from East and West Asia (Pushparatnam Reference Pushparatnam2015: 88–90), point to both the presence of vulnerable earlier sub-surface heritage and the site's potential time-depth and place in island-wide and Indian Ocean exchange networks (Ragupathy Reference Ragupathy1987; Rajan & Rama Reference Rajan and Raman1994; Begley Reference Begley1996; Weisshaar et al. Reference Weisshaar, Roth and Wijeyapala2001; Coningham Reference Coningham2006; Carswell et al. Reference Carswell, Deraniyagala and Graham2013).

The ‘Jaffna Fort Post-Disaster Archaeological Research Project’ responded to this context in 2017 by beginning to map, identify and characterise its cultural sequences through excavation, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys (Figure 2). Transposing methodologies for post-disaster heritage co-designed in post-earthquake Nepal (Coningham et al. Reference Coningham, Acharya, Davis, Weise, Kunwar, Simpson, Bracke, Ruszczyk and Robinson2018) (Figure 3), the team aimed to protect archaeologically sensitive areas as well as refine typologies from Jaffna's first scientifically dated sequences.

Figure 2. Professor Pushparatnam, Director, CCF Jaffna and Professor Gunawardhana, Director-General CCF, with participants from the University of Jaffna and CCF at the start of the 2017 field season.

Figure 3. Post-disaster excavations at the Kruys Kerk.

GPR survey identified rectilinear anomalies below the Parade Ground (Figure 4) that may represent structures from the Portuguese Fort, including the church, ‘Our Lady of Miracles’, which was cleared by the Dutch. Although monuments from earlier periods were destroyed, there is a history of reincorporation with earlier tombstones and bells reinterred inside the Dutch-era Kruys Kerk and pre-colonial carved granite blocks within rubble at the site, probably recycled from Hindu temples demolished by the Portuguese (Pushparatnam Reference Pushparatnam2015: 96–98).

Figure 4. UAV map of Jaffna Fort (processed with Pix4Dmapper software) with GPR survey results at a depth of 0.8m.

In addition to European-produced artefacts, pre-colonial contact materials were successfully recovered, particularly from excavations close to a new septic tank (Figure 5). Black and Red Ware, Dusun Jars, Early Islamic glazed wares, Rouletted Ware and Ming porcelain were excavated from contexts without European-contact artefacts, confirming the pre-colonial significance of Jaffna Fort. Importantly, new ceramic types were identified, including sherds exhibiting rouletting and stamped radial designs, illustrating both Jaffna's uniqueness and central place within international Indian Ocean networks (Figure 6). Unfortunately, these finds were from within mixed deposits above the natural bedrock. While we await scientific dating confirmation, the terminus ante quem for the earliest phases is estimated to be the seventh or eighth century AD, although many individual items date to the first millennium BC.

Figure 5. Excavations near the new toilet block and septic tank.

Figure 6. Artefacts from the 2017 excavations.

Further HEFCE-GCRF-sponsored excavations will investigate the GPR anomalies potentially representing Portuguese-era monuments, and continue to seek secure stratigraphic sequences to provide robust scientifically dated evidence for the origins of Jaffna and its role within the development of international trade and communication networks before and beyond European contact.

Acknowledgements

The 2017 fieldwork was sponsored by the British Academy (SG162515), the Institute of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (Durham University), with support from the Central Cultural Fund and Department of Archaeology (Government of Sri Lanka), the PGIAR (University of Kelaniya) and the Universities of Jaffna and Durham.