Article contents

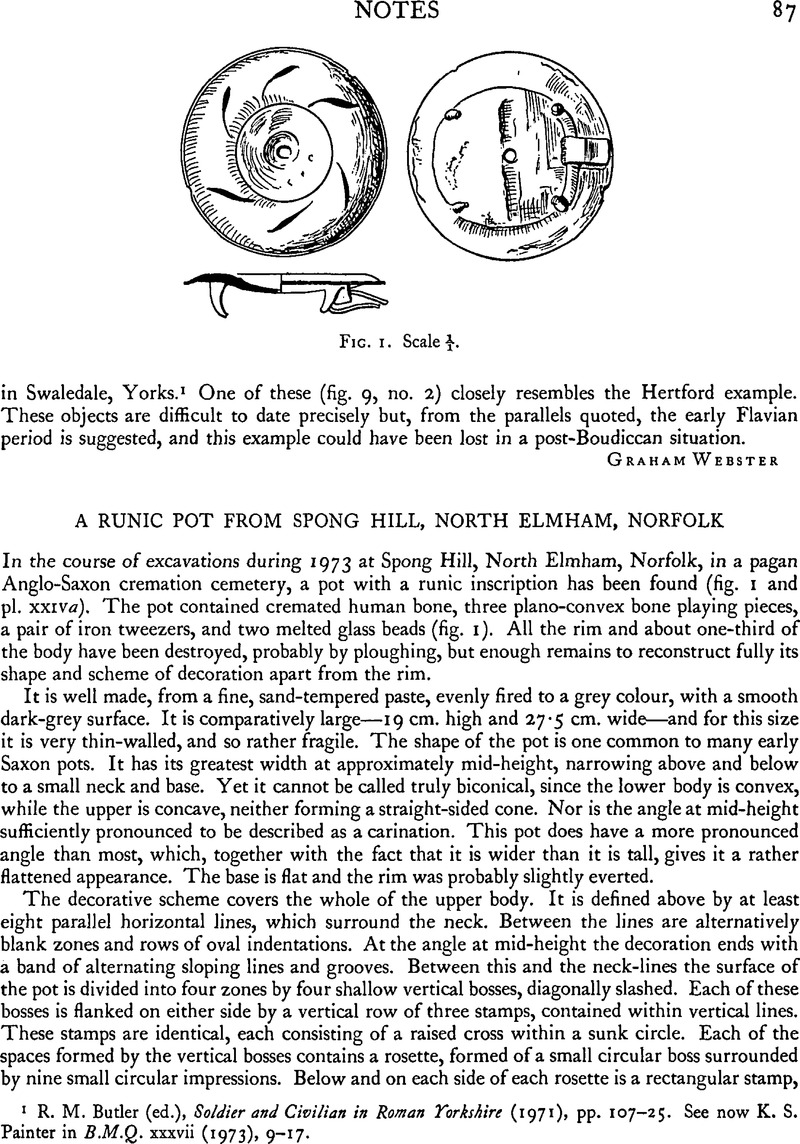

A Runic Pot from Spong Hill, North Elmham, Norfolk

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1974

References

page 88 note 1 Hawkes, S. C. and Page, R. I., ‘Swords and Runes in South-east England’, Antiq. Joum. xlvii (1967), 7Google Scholar, pl. iii a.

page 88 note 2 Dickens, B., ‘A System of Transliteration Old English Runic Inscriptions’, Leeds Studies English, i (1932). 17Google Scholar.

page 88 note 3 This rune occurs in eighth-century Northumbria, for example on the Ruthwell Cross (The Dream of the Rood, ed. B. Dickens and A. Ross (1934)).

page 88 note 4 Keller, W., ‘Zur Chronologie der AE Runen’, Anglia, lxii (1938)Google Scholar.

page 89 note 1 Jonsson, Finnur, Saemundar Edda (1926), 308Google Scholar, Sigrdrifumal v. 5.

page 89 note 2 Ibid.

page 89 note 3 Evison, V. I., ‘An Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Holborough, Kent’, Arch. Cant, lxx (1956)Google Scholar.

page 89 note 4 Beowulf, ed. Klaeber, F. (3rd edn., 1941), 1695Google Scholar.

page 89 note 5 Dr. Calvin Wells has analysed cremations from the 1968 season at Spong Hill, and all those containing playing pieces proved to be male. I am grateful to Miss B. Green, of Norwich Castle Museum, for this information.

page 89 note 6 Evison, V. I., ‘The Dover Rune Brooch’, Antiq. Journ. xliv (1964), 242–5CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

page 89 note 7 Krause, W., Die Runen Inschriften im alteren Futhark (1966), 6Google Scholar.

page 89 note 8 Arntz, H. and Zeiss, H., Die einheimischen Runendenkmäler des Festlandes (1939), 42Google Scholar, 97, Taf. 2 and 5. Dr Page doubts whether these are in fact runic; see Page, R. I., ‘The Use of Double Runes in Old English Inscriptions’, Journal of English and German Philology, lxi (1962), 897Google Scholar.

page 89 note 9 Zimmer-Linnfeld, , Westeruianna, i (1960)Google Scholar, Taf. 36, no. 268, Taf. 48, no. 369; Waller, K., Die Graierfeld von Altenwalde (1957)Google Scholar, Taf. 2, 17, Taf. 17, 152.

page 89 note 10 Myres, J. N. L., Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England (1969), pp. 139–41Google Scholar, figs. 50 and 51.

page 90 note 1 Myres, op. cit. 1969.

page 90 note 2 Lethbridge, T. C., A Cemetery at Lackford, Suffolk (Camb. Ant. Soc. 4to pubn. ser. vi, 1951)Google Scholar, 20, fig. 27, no. 49, 39.

page 90 note 3 Evison, op. cit. 1964.

page 90 note 4 Hawkes and Page, op. cit. 1967, 22.

page 90 note 5 Myres, op. cit. 1969, 37–8.

page 90 note 6 Waller, K., Die Graberfelder von Hemmoor, Que/khm, Gudendorf and Duhnen-Wehrberg (1959)Google Scholar, Taf. 25, no. 20, shows a pot alike in both form and decoration to the Loveden runic pot.

page 90 note 7 Hubener, W., Aisalz Geiiete frühgeschichtliche Töpfereien in der Zone nordlich der Alpen (1969)Google Scholar, Taf. 161.

page 90 note 8 These pots will all be fully described and illustrated in the final publication of the whole cemetery.

page 90 note 9 Myres, J. N. L., ‘Three Styles of Decoration on Anglo-Saxon Pottery’, Antiq. Journ.xvn (1967), 424–37Google Scholar, pl. xci a.

page 90 note 10 Capelle, T. and Vierck, H., ‘Modeln der Merovingerzeit und Vikingerzeit’, Frühmittelalterliche Studien (1971)Google Scholar.

page 91 note 1 It occurs in the east German ‘Schalenurnen-felder’ of the third and fourth centuries (cf. Schuldt, E., Pritzier (1955)Google Scholar), and is also found further west, in Frisia, as well as elsewhere in England. It is not a common English form.

page 91 note 2 Evison, V. I., ‘Five Anglo-Saxon Inhumation Graves Containing Pots at Great Chesterford’, Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheid-kundig Bodermonderxoek, xix (1969), 166, fig. 4Google Scholar.

page 91 note 3 For a detailed discussion of the runic astragalus see Wrenn, C. L., ‘Magic in an Anglo-Saxon Cemetery’, English and Medieval Studies presented to J. R. R. Tolkien (1962), 306 ffGoogle Scholar.

page 91 note 4 Hawkes and Page, op. cit. 3–6,23, pi. 1, pl. iva.

page 91 note 5 Page, R. I., ‘Anglo-Saxon Runes and Magic’, J.B.A.A. xxvii (1964)Google Scholar.

page 91 note 6 Krause, op. cit. 1966, includes many instances of this.

- 1

- Cited by