No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

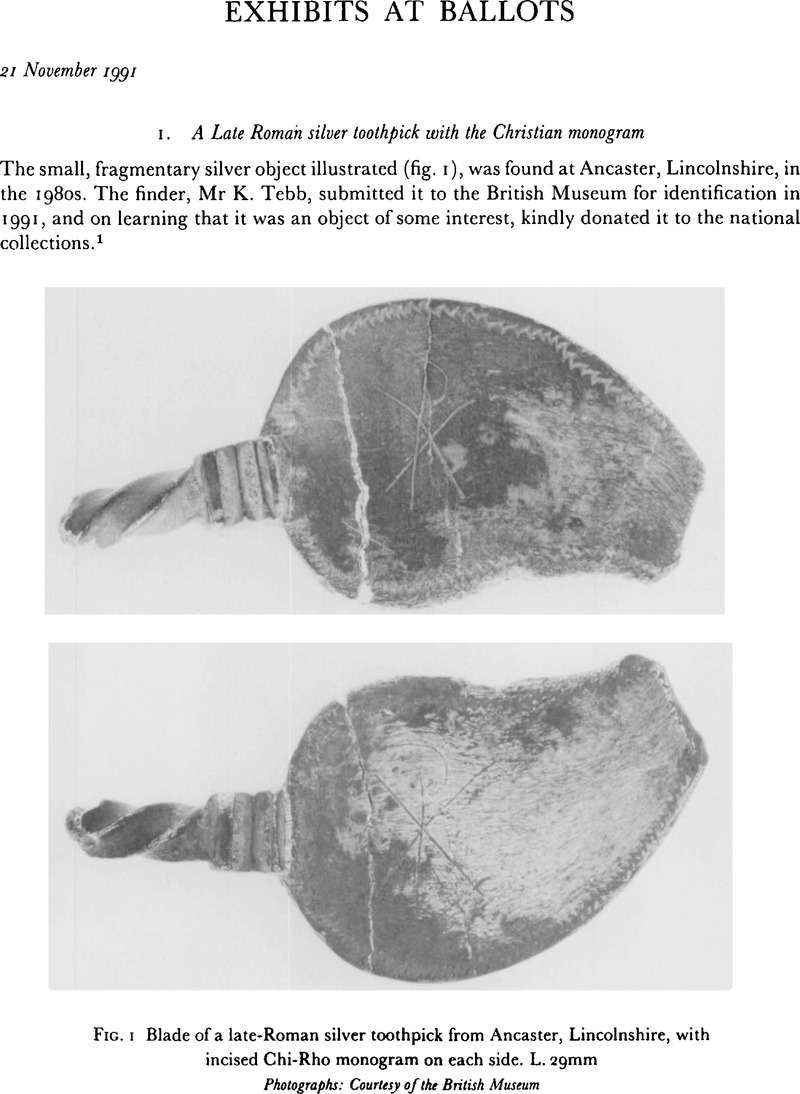

Exhibits at Ballots

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Exhibits at Ballots

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1992

References

NOTES

page 191 note 1 Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities, registration no. P.1991.6–1.1.

page 191 note 2 Semi-quantative X-ray fluorescence analysis in the British Museum Research Laboratory indicated a silver content of 96 per cent. I am grateful to my colleague Duncan Hook for this information.

page 191 note 3 Kaiseraugst: Cahn, H. A. and Kaufmann-Heinimann, A., Der spätrömische Silberschatz von Kaiseraugst (Derendingen, 1984, 124–31).Google Scholar Canterbury: Johns, C. M and Potter, T. W., ‘The Canterbury Late Roman Treasure’, Antiq. J., 65 (1985), 333.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Thetford: Johns, C. M and Potter, T. W., The Thetford Treasure (London, 1983), No. 49.Google Scholar Hoxne: for interim publications, see Bland, Roger and Johns, Catherine, The Hoxne Treasure, an illustrated introduction (London, 1993) and Bland, Roger and Johns, Catherine in Britannia, 25 (1994), forthcoming.Google Scholar

page 191 note 4 Charles, Thomas, Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500 (London, 1981), 236–7Google Scholar, and Dorothy, Watts, Christians and Pagans in Roman Britain (London, 1991), numerous references.Google Scholar

page 191 note 5 British Library Add MS 18667; printed (rather inaccurately) in Revd Thomas, Harwood, A Survey of Staffordshire… by Sampson Erdeswick Esq. (1820, Westminster) after page 136 (though the Bodleian copy has it at page 126).Google Scholar

page 191 note 6 Waters, Robert E. Chester, Genealogical Memoirs oj the Chesters of Chicheley (London, 1878), 1, 93–107.Google Scholar

page 191 note 7 Staffs, V.C.H.., Vol. 5 (London, 1959), 149–73.Google Scholar

page 191 note 8 ‘The Visitacion of Staffordshire made by Robert Glover al's Somerset Herald Anno D'ni 1583’, William Salt Society Hist. Colls., 3 (ii) (1883), 29.Google Scholar

page 191 note 9 ‘Heraldic Visitations of 1614 and 1664’, William Salt Society Hist. Colls., 5 (ii) (1885), 303, 338.Google Scholar

page 191 note 10 d'Elboux, R. H., ‘The Dering Brasses’, Antiq. J. 27 (1947). 11–23.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 191 note 11 See Malcolm, Norris, Monumental Brasses, The Memorials. (London, 1977), 2, 313, note 8.Google Scholar

page 191 note 12 A fuller version of this paper will be found in Church Monuments 8 (1993), 57–62.Google Scholar

page 191 note 13 Woodward, John; ‘The Monument to Sir Thomas Bodley in Merton College Chapel’, Bodleian Library Record, 5 (1954–1956), 69–73.Google Scholar

page 191 note 14 Dante's Convivio (trans. William Walrond Jackson) (Oxford, 1909), 106.Google Scholar

page 191 note 15 Carlisle: Page, R. I., An Introduction to English Runes (London, 1973), 196.Google Scholar

page 191 note 16 For a geographical distribution of finds of runic inscriptions in England see Elliott, Ralph W. V., Runes an Introduction (2nd. edition, Manchester, 1989), 48–59; Page 1973 (note 15) 25–33.Google Scholar

page 191 note 17 Edward, Charlton, ‘On an Inscription in Runic Letters in Carlisle Cathedral’, Archaeol. Aeliana, 3 (1859), 65–8;Google Scholar George, Stephens, The Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England, 4 vols. (London, 1866–1901), 11 (1867), 663.Google Scholar Stephens is recorded as commenting upon this inscription during a visit to Carlisle, Cathedral, ‘Excursions and Proceedings’, Trans. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiq. and Archaeol. Soc. (1883), 500.Google Scholar

page 191 note 18 For convenience of graffiti location, see Doris, Jones-Baker ‘Mediaeval Music and Musicians in Hertfordshire: the Graffiti Evidence’, Hertfordshire in History (Linton, 1991), 26.Google Scholar

page 191 note 19 For the position of medieval graffiti as evidence for rebuilding, see Doris, Jones-Baker, ‘The Graffiti of England's Medieval Churches and Cathedrals’, Churchscape (Council for the Care of Churches, 1987), 9, 11, No. 6.Google Scholar

page 191 note 20 Drawings of men's heads are among the most numerous subjects for English medieval graffiti, and a number of them survive elsewhere in the crypt and in other parts of Canterbury Cathedral. Notable examples in the crypt are engraved in the medieval plaster on the east face of the reredos of the chapel of Our Lady Undercroft, and cut in the stonework of the wall to the north of the south doorway leading to the crypt stairs. None of these graffiti drawings, however, appear to be as old as those in St Gabriel's chapel, and they seem to have been cut at random and by different hands.

page 192 note 21 Several stylized graffiti drawings of triangular human heads are cut on pillars in the north arcade at St Leonard's church at Flamstead (Herts.). See Doris Jones-Baker, Hertfordshire's Historic Graffiti, forthcoming. For the medieval iconography of the severed head in Christian churches, see Ronald, Sheridan and Anne, Ross, Grotesques and Gargoyles Paganism in the Medieval Church (Newton Abbot, 1975). 52–3Google Scholar

page 192 note 22 According to legend, Veronica, one of the women following Christ to Calvary, wiped his bleeding face and found his image impressed upon her handkerchief.

page 192 note 23 Among other examples, there is a good votive graffito drawing of a vernicle on the front of the gabled cabin of the medieval windmill engraved in Newnham church, Hertfordshire. See Doris Jones-Baker, Hertfordshire's Historic Graffiti, forthcoming.

page 192 note 24 Cryptic runes are found in the works of Cynewulf (750–825) who is notable for having used runes as cryptograms to conceal his name while thus recording it, and other Anglo-Saxon writers. Elliott 1989 (note 16), 55.

page 192 note 25 Vera, Evison, ‘The Dover Rune Brooch’, The Antiq. J., 44(1964), 242–5.Google Scholar

page 192 note 26 Elliott 1989 (note 16), 50.

page 192 note 27 This stone is now at Winchester City Museum. Kjølbye-Biddle, B. and Page, R. I., ‘A Scandinavian Rune-stone from Winchester’, The Antiq. J., 55 (1975), 389–94CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 192 note 28 Jones-Baker collection of English medieval graffiti. A number of medieval cryptograms, for example, used musical notation, as in the graffiti inscriptions at Lydgate church, Suffolk, and Little Waltham and Rayleigh churches in Essex. See Doris Jones-Baker and Judith Blezzard, The Graffiti of English Medieval Music, forthcoming.

page 192 note 29 See Doris, Jones-Baker, ‘English Medieval Graffiti and the Local Historian’ The Local Historian, 23, no 1 (1993). 4–6Google Scholar

page 192 note 30 Derolez, R. and Schwab, U., ‘The Runic Inscriptions of Monte Sant Angelo (Gargano)’, Academiae Analecta (Mededelingen Letteren) 45 (1983). According to Elliott 1989 (note 16), 58 ‘Three of the names are reasonably unambiguous: Wigfus, Herraed, and Hereberehct. A fourth name is more dubious, but it is worth noting that yet another name, probably also Anglo-Saxon—Eadrhid Saxo—in Roman letters appears at some remove in the same sanctuary’.Google Scholar

page 192 note 31 Warner, S. A., Canterbury Cathedral (London, 1923), 96Google Scholar

page 192 note 32 Doris Jones-Baker 1993 (note 29), 12–13.

page 192 note 33 Elliott 1989 (note 16), 55–8.

page 192 note 34 Ibid., 59.

page 192 note 35 Letts, M., Sir John Mandeville, the Man and His Book (London, 1949), 151–160Google Scholar; Derolez, R., Runica Manuscriptica, the English Tradition (Bruges, 1954), 275Google Scholar

page 192 note 36 For the difficulties of dating English medieval graffiti, see Doris Jones-Baker 1993 (note 29), 2.

page 192 note 37 For the architectural history of St Gabriel's chapel, see Woodman, Francis, The Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral (London, 1981), 49–53.Google Scholar

page 192 note 38 ‘A date for this alteration of c. 1100 can be proposed from the appearance of a broken billet string course across the new work, a motif employed on the exterior of the main level chapels, and the continuity of the base plaster of the paintings in the apse’. Ibid., 53.

page 192 note 39 Additional strengthening also took place at this time in Holy Innocents Chapel, ibid.

page 192 note 40 Hill, Revd Canon D. Ingram, Canterbury Cathedral (London, 1986), 165. Canon Ingram Hill witnessed the final demolition of the supportive wall in St Gabriel's chapel. I am grateful to him for information about St Gabriel's chapel and the graffiti elsewhere in Canterbury Cathedral.Google Scholar

page 192 note 41 Registration MLA 1992, 5–3, 2.

page 192 note 42 Report by P. T. Craddock, British Museum Department of Scientific Research. For other bronzes see Oddy, W. A. ‘Bronze alloys in Dark-Age Europe’ in The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial (Bruce-Mitford, R. L. S.) III (London, 1983), 945–61.Google Scholar

page 192 note 43 Haseloff, G., Email im Frühen Mittelalter. Frühchristliche Kunst von der Späntike bis zu den Karolingern, Marburger Studien zur Vor- Und Frühgeschichte 1 (Marburg, 1990), 153–206.Google Scholar

page 192 note 44 Haseloff, 1990 (note 43); Hughes, M.J., ‘Enamels: materials, deterioration and analysis’ in From Pinheads to Hanging Bowls (eds. Bacon, L. and Knight, B.), United Kingdom Institute for Conservation Occasional Papers, 7 (London, 1987), 10–12.Google Scholar

page 192 note 45 Bateson, J. D., Enamel-Working in Iron Age, Roman and Sub-Roman Britain, Brit. Archaeol. Rep. Brit. Ser., 93 (Oxford 1981), 68.Google Scholar

page 192 note 46 Bimson, M., ‘Coloured glass and millefiori in the Sutton Hoo grave deposit’ in Bruce-Mitford 1983 (note 42), 937–8.Google Scholar

page 192 note 47 Oddy, W. A., Bimson, M., Cowell, M., ‘Scientific examination of the Sutton Hoo hanging-bowls’ in Bruce-Mitford 1983 (note 42), 303, and Craddock report (note 42).Google Scholar

page 192 note 48 Leeds, E. T., Celtic Ornament in the British Isles down to AD 700 (Oxford, 1933), 150–1, pl. III.7. This mount is now in the Hunt collection, Limerick.Google Scholar

page 193 note 49 On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Information kindly supplied by Dr R. L. S. Bruce- Mitford, F.S.A., in advance of his own publication. He dated the escutcheon to the late sixth century.

page 193 note 50 Vierck, H., ‘Cortina Tripodis’, Frühmittelalterliche Studien, 4 (1970), 8–52, in particular 32–3.Google Scholar

page 193 note 51 Floinn, R.Ó, ‘A fragmentary house-shaped shrine from Clonard, Co. Meath’, J. Ir. Archaeol., 5 (1990), 53, where the colour is described as green.Google Scholar

page 193 note 52 Youngs, S. M. (ed.), ’The Work of Angels’ Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th-9th Centuries AD (London, 1989), 38, 61.Google Scholar

page 193 note 53 Bonde, N. and Christensen, A. E., ‘Dendrochronological dating of the Viking Age ship burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, Norway’, Antiquity, 67 (1993), 573–83CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 193 note 54 Bourke, C. and Close-Brooks, J., ‘Five Insular enamel ornaments’, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 119 (1989), 227–37; Pers comm. R. M. Spearman.Google Scholar

page 193 note 55 Henry, F., ‘Irish enamels of the Dark Ages and their relation to the Cloisonné techniques’ in Dark Age Britain. Studies presented to E. T. Leeds (ed. Harden, D. B.) (London, 1956), 84–6.Google Scholar

page 193 note 56 Organ, R. M., ‘Examination of the Ardagh chalice — a case history’ in Application of Science in Examination of Works of Art, (ed. Young, W. J.) (Boston, 1973), 236–71, where the construction of the handles is shown and discussed on 264, figs. 57–8Google Scholar

page 193 note 57 Ibid., 264, fig. 56; a similar construction is described on the Derrynaflan strainer, Ó Floinn in Youngs 1989 (note 52), 132.

page 193 note 58 Trinity College Dublin MS A.4.5 (57); Alexander, J.J., Insular Manuscripts 6th to the 9th Century (London, 1978), No. 6.Google Scholar

page 193 note 59 D.330, kindly brought to my attention by Raghnall Ó Floinn; to be published by S. Youngs ‘Cloisonné work and the origins of polychrome enamelling’, papers of the 3rd Insular Art Conference Belfast 1994, (ed. C. Bourke); the Durrow carpet pages are published in J.J. Alexander 1978 (note 58), ill. 17–21.

page 193 note 60 Bourke, C., Patrick: The Archaeology of a Saint (H.M.S.O. Belfast, 1993), 33.Google Scholar

page 193 note 61 Youngs forthcoming (note 59).

page 193 note 62 Respectively Youngs 1989 (note 52), 60; Hencken, H.O'N., ‘Lagore Crannog: an Irish royal residence of the 7th to 10th centuries AD’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 53 C (1951), 121; Bourke and Close-Brooks 1989 (note 54), 232–5.Google Scholar

page 193 note 63 Spearman, R. M., ‘The mounts from Crieff, Perthshire, and their wider context’, in The Age of Migrating Ideas, (eds. Spearman, R. M. and Higgitt, J.), Proceedings of the Second Conference on Insular Art (Edinburgh, 1993), 135–42.Google Scholar

page 193 note 64 Blindheim, M., ‘A house-shaped Irish-Scots reliquary in Bologna, and its place among the other reliquaries’, Ada Archaeologia, 55 (1984), 1–53; Ó Floinn 1990 (note 51), 53.Google Scholar

page 193 note 65 Kelly, M. J. O ‘The belt-shrine from Moylough, Sligo’J. Roy. Soc. Antiq lre., 95 (1965), 157–8, fig. 3Google Scholar

page 193 note 66 Earwood, C., Domestic Wooden Artefacts in Britain and Ireland from Neolithic to Viking Times (Exeter, 1993),105–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 193 note 67 Blindheim 1984 (note 64); Ó Floinn 1990 (note 51), 53.

page 193 note 68 Speake, G., A Saxon Bed Burial on Swallowcliffe Down, English Heritage Archaeol. Rep. 10 (London, 1991), 26–30, fig. 26.Google Scholar

page 193 note 69 British Museum MLA 1992, 5–2, 1.

page 193 note 70 Colleagues in several museums have helped my research into Celtic enamels and been most generous with both their time and access to unpublished material: I would like to thank in particular Raghnall Ó Floinn and Eamonn Kelly of the National Museum of Ireland, and Cormac Bourke of the Ulster Museum. I have a special debt to Leslie Webster, F.S.A., for her advice and information on early caskets.