No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2011

1 Richter, G. M. A., Furniture of the Greeks and Romans (Oxford, 1966), III-12, type 3Google Scholar.

2 Liversidge, J., Furniture in Roman Britain (London, 1955), 42, fig. cGoogle Scholar.

3 e.g. Liversidge, , op. cit., pl. 1, 3, and 6–12Google Scholar.

4 See the discussion by Liversidge, , op. cit., 37–53Google Scholar.

5 Solley, T. W. J., ‘Romano-British side-tables and chip-carving’, Britannia, x (1979), 169–78CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

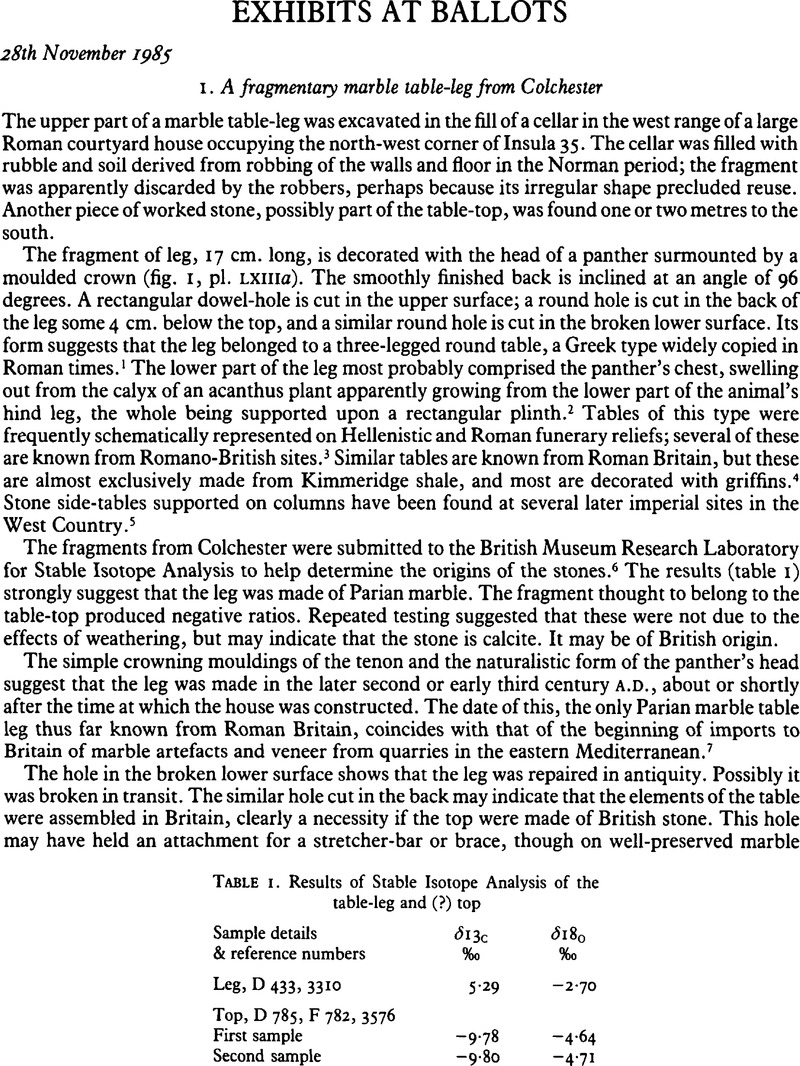

6 For the method of analysis, see McCrea, J. M., ‘The isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale’, J. Chem. Phys. xviii (1950), 849–57CrossRefGoogle Scholar; for its application to classical marbles, see most recently Herz, N. in Rapp, G. Jr and Gifford, J. A.), Archaeological Geology (London and New Haven, 1985), 331–51Google Scholar.

7 For recent discoveries, see Walker, S., Britan-nia, xv (1984), 149–60Google Scholar, and the forthcoming publication in Britannia, xvii, of finds of marble from Roman London.

8 e.g. Richter, , op. cit. (note 1), figs. 572 and 577Google Scholar.

9 See Archaeology in Lincolnshire 1984-5, First Annual Report of the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology, October, 1985,44-52.1 would like to thank the Trust, especially its Director, Michael Jones, F.S.A., for unstinting help in preparing this short paper.

10 Heslop, T. A., ‘English seals from the mid-ninth century to c. 1100’, J.B.A.A. cxxxiii (1980), 1–16Google Scholar.

11 For examples of seals cancelled by removing a name or all of the legend see Cox, D. C. and Heslop, T. A., ‘An eleventh-century seal matrix from Evesham, Worcs.’, Antiq. J. lxiv (1984), 396Google Scholar, and Tonnochy, A. B., Catalogue of British Seal Dies in the British Museum (London, 1952), no. 858, p. 184Google Scholar.

12 e.g. Latham, R. E., Revised Medieval Latin Word-List from British and Irish Sources (London, 1965), 272Google Scholar.

13 Whitelock, D., Brett, M. and Brooke, C. N. L., Councils and Synods with other Documents relating to the English Church, i (Oxford, 1981), 563–604 and 625-9Google Scholar.

14 Several can be found in Temple, E., Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts 900-1066 (London, 1976), illus. 91, 247 and 256Google Scholar.

15 The Letters of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, ed. Clover, H. and Gibson, M. (Oxford, 1979), 84–7Google Scholar, including useful footnotes.

16 For this representation, see Leroquais, V., Les Sacramentaires et les missels manuscrits des bibliothe-ques publiques de France (Paris, 1924)Google Scholar, plates vol., v, from the ninth-century Autun/Marmoutier sacramentary.

17 English Romanesque Art 1066-1200, exhibition catalogue, Gallery, Hayward (1984), nos. 373–4, p. 318Google Scholar, and Okasha, E., ‘A supplement to the handlist of Anglo-Saxon non-runic inscriptions’, Anglo-Saxon England, xi (1983), nos. 177 and 184, pp. 99 and 103Google Scholar.

18 Of the seals discussed by Heslop, (op. cit. (note 10))Google Scholar, only Athelney, of uncertain date, and then Anglo-Norman seals such as those of Gundulf, bishop of Rochester, and Ralph Flambard, bishop of Durham, have single-dot punctuation. Punctuation and word separation are notably lacking on seals from c. 1050 such as the Confessor's or Exeter Cathedral's and are still absent from the Conqueror's.

19 Ibid., 10.

20 If it is sun and moon that we are shown, it may be for reasons of propaganda. Gregory VII, in a letter to William the Conqueror in 1080, compares the apostolic dignity to that of the sun, while the royal is comparable to the moon (that is, reflected glory): see Das Register Gregors VII, ed. Caspar, Erich (Berlin, 1923), ii, 505–6Google Scholar. However, given its small size on the seal it is perhaps more likely that a star is shown beside the moon, in which case the reference is perhaps to Psalm 8 verse 3 and the association with man's ability to act as God's agent.

21 Bishop, T. A. M. and Chaplais, P., Facsimiles of English Royal Writs to A.D. 1100 (Oxford, 1957), p. xiiiGoogle Scholar.

22 It seems that when he first arrived to deal with Anglo-Norman affairs Hubert was a lector, but was ordained subdeacon perhaps while on his mission: cf. Whitelock, et al., op. cit. (note 13), 626 n. 1Google Scholar.

23 The chasuble-like garment which he wears seems to have an integral hood rather than a separate amice. If it is a chasuble proper it would be at least unusual for a subdeacon to wear it. However, the whole issue is difficult to resolve: see Legg, J. Wickham, Church Ornaments and their Civil Antecedents (Cambridge, 1917), ch. v passim, esp. 40–1Google Scholar.

24 On the assumption that the altar is vertical, one can reconstruct the position of the lost + which began the legend. I calculate that there is space for seven letters missing at the beginning and five at the end of the legend. This would allow the first word to be HUBERTI. While one might wish LEGATIO to have been LEGATIONIS (in the genitive), that leaves no room for a subject for the verb, and it is hard, anyway, to imagine what it might have been.

25 Horton, M. and Clark, C., Zanzibar Archaeological Survey 1984/5, for the Ministry of Information, Culture and Sport (Zanzibar, 1985)Google Scholar; al-Mascudi and Monclaro, apud Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P., The East African Coast: Select Documents (1962, 2nd edn. 1975), 15, 16, 140Google Scholar; Vaccaro, V., Le Monete di Aksum (Mantua, 1967), 34–6Google Scholar; Zambaur, E.de, Manuel de genealogie et de chronologie pour I'histoire de Islam (Bad Pyrmont, 1955), 97–101Google Scholar.

26 My thanks go to Mr Kings and to Mr R. Moore of Northampton Museum for providing all the necessary contextual information on the find and allowing me to publish it. The object is to be acquired by Northampton Museum.

27 British Museum Research Laboratory.

28 Smith, C. S., A Search for Structure-Selected Essays on Science, Art and History (Cambridge, Mass., 1982), 83–4Google Scholar. Hughes, M. J., Northover, P. and Staniasek, B., ‘Problems in the analysis of leaded bronze alloys in ancient artefacts’, Oxford J. Arch, i (1982), 359–63CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

29 Brown, M. A., and Blin-Stoyle, A. E., ‘A sample analysis of British Middle and Late Bronze Age material’, P. P. S. xxv (1959), 188–208Google Scholar; the analyses themselves are listed in Archaeometry, 2nd supplement (1959), 1-24.

30 Hawkes, C. F. C. and Smith, M. A., ‘On some buckets and cauldrons of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages’, Antiq. J. xxxvii (1957), 131–98CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

31 Briggs, S., forthcoming: ‘Buckets and cauldrons in the Late Bronze Age of north-west Europe: a review’, in Blanchet, J. C., Les Relations entre le Continent et les lies Britanniques à Î'âge du bronze, Proceedings of the Lille Conference, 1984Google Scholar. I am very grateful to Dr Briggs for allowing me to consult this paper in advance of its publication.

32 Cape Castle Bog, Co. Antrim; Dervock, Co. Antrim; Cardross, Stirlingshire; Heathery Burn, Co. Durham; Briggs, , op. cit. (note 31), nos. 4, 5, 8 and 16Google Scholar; Hawkes, and Smith, , op. cit. (note 30), 150 fig. 5Google Scholar.

33 Hatfield, Herts: Davies, G., ‘Hatfield Broadoak, Leigh, Rayne, Southchurch: Late Bronze Age hoards from Essex’, in Burgess, C. B. and Coombs, D. (eds), Bronze Age Hoards: some Finds Old and New, B.A.R. 67 (Oxford, 1979)Google Scholar. Bagmoor, Lines: Smith, M. A., Bronze Age Hoards and Grave-Groups from the North-east Midlands, Inventaria Archaeologica G.B. 19–24 (London, 1957)Google Scholar. South Cadbury, Somerset: Alcock, L., ‘South Cadbury Excavations 1969’, Antiquity, xliv (1970), 46–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

34 O'Connor, , Cross-Channel Relations in the Later Bronze Age, B.A.R. S91, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1980), 147–8Google Scholar. Needham, S.P., ‘Two recent British shield finds and their Continental parallels’, P.P.S. xlv (1979), 111–34Google Scholar.

35 I am grateful to Roger Miket, Senior Museums Officer, South Shields Museum, for lending the cameo and providing details of the context. Our Fellow Robert Wilkins kindly provided the photograph.

36 Henig, M., A Corpus of Roman Engraved Gemstones from British Sites, B.A.R. 8, 2nd edn. (Oxford, 1978), 307 and pl. xxx, no. App. 150)Google Scholar; Babelon, E., Catalogue des camees antiques et modemes de la Bibliotheque Nationale (Paris, 1897), 42 and pl. viii, no. 69Google Scholar. The cameo is burnt and somewhat crazed.

37 Ibid., 156 and pl. xxxiv, no. 300 (sardonyx cameo showing busts of Septimius Severus, Julia Domna, Caracalla and Geta), and 157, pl. xxxiv, no. 302 (sardonyx cameo depicting bust of youthful Caracalla); Zazoff, P., Staatliche Kunstsam-mlungen Kassel. Antike Gemmen (Kassel, 1969), 28 and pl. 28, no. 63Google Scholar; For the bear cameo, see Henig, , op. cit. (note 36), 274 and pl. LIIIGoogle Scholar, no. 735= Allason-Jones, L. and Miket, R., The Catalogue of Small Finds from South Shields Roman Fort, Soc. Antiq. Newcastle upon Tyne, monograph series, 2 (Newcastle, 1984), 342 and pl. XI, no. 10.1Google Scholar. For a slightly older lightly bearded Caracalla, cf. Montesquiou-Fezensac, B. de and Gaborit-Chopin, D., ‘Camées et intailles du Trésor de Saint-Denis’, Cahiers Arch, xxiv (1975), 150 and fig. 16 no. 6Google Scholar.

38 e.g. Mattingly, H. and Sydenham, E. A., The Roman Imperial Coinage, iv. pt. 1: Pertinax to Geta (London, 1936), 226, no. 89 (A.D. 207)Google Scholar. I am most grateful to Dr Cathy King for a photograph of a specimen in the Heberden Coin Room, Ashmolean Museum. For a marble portrait of about this time, see Wiggers, H. B., ‘Caracalla’, in Wegner, M. (ed.), Das romische Herrscherbild (Berlin, 1971), 74, pl. 8Google Scholar.

39 Bruce, J. Collingwood, ‘On the recent discoveries in the Roman camp on the Lawe, South Shields’, Arch. Ael. 2nd ser. x (1885), 266Google Scholar, no. 9=Henig, , op. cit. (note 36), 247, no. 482Google Scholar, and , Alla-son-Jones and Miket, , op. cit. (note 37), 345, no. 10.11Google Scholar.

40 Blair MS. I am likewise indebted to Mr Miket for the loan and to our Fellow, Robert Wilkins, for the photograph.

41 Dore, J. N. and Gillam, J. P., The Roman Fort at South Shields. Excavations 1875-1975, Soc. Antiq. Newcastle upon Tyne, monograph series, 1 (Newcastle, 1979), 61–6Google Scholar.

42 Ibid., 164, nos. 1–8; also , Allason-Jones and Miket, , op. cit. (note 37), 327–8, nos. 8–21Google Scholar.

43 Frere, S., ‘The Roman theatre at Canterbury’, Britannia, i (1970), 83–113, see esp. 87-91 and 111-12CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Milne, G., The Port of Roman London (London, 1985), 32Google Scholar; Merrifield, R. in Hill, C., Millett, M. and Blagg, T., The Roman Riverside Wall and Monumental Arch in London, London & Middlesex Arch. Soc. special paper, 3 (1980), 203–4Google Scholar; Richmond, I. A. in R.C.H.M. (England), Eburacum. Roman York (London, 1962), xxxviGoogle Scholar.

44 Henig, M., ‘An intaglio and sealing from Blackfriars, London’, Antiq. J. lx (1980), 331–2, pl. LXbGoogle Scholar.

45 I am grateful to Christine E. Jones for sending the drawing, which is by Terry Shiers.

46 Henig, , op. cit. (note 36), 198, pls. iv and xxxiv, no. 103Google Scholar.

47 Richter, G. M. A., Engraved Gems of the Romans (London, 1971), 118, no. 583Google Scholar.

48 cf. Henig, M., ‘Graeco-Roman art and Rom-ano-British imagination’, J.B.A.A. cxxxviii (1985), 13 Pl. IIIGoogle Scholar.

49 Blair, R., Proc. Soc. Antiq. Newcastle, ii (1885), 147Google Scholar; Henig, , op. cit. (note 36), 229–30Google Scholar, and Religion in Roman Britain (London, 1984), 181–2, also 116Google Scholar.

50 Bowdman, J., Engraved Gems. The Ionides Collection (London, 1968), 28 and 94, no. 19, frontispieceGoogle Scholar. For the Gemma Augustea see Oberleitner, W., Geschnittene Steine. Die Prunkkameen der Wiener Antikensammlung (Vienna, 1985), 40–4Google Scholar. Early Imperial gems cut for court circles are discussed by Vollenweider, M. L., Die Steinschneide-kunst und ihre Künstler in spätrepublikanischer und augusteischer Zeit (Baden-Baden, 1966)Google Scholar: heroic and divine imagery is frequently found.

51 Ead. Deliciae Leonis. Antike geschnittene Steine und Ringe aus einer Privatsammlung (Mainz, 1984), 189–90, no. 312Google Scholar.

52 S.H.A., Caracalla, 5. Oberleitner, , op. cit. (note 50), 63, pl. 45Google Scholar.

53 For the text of this letter and its date, see Labarte, J., Histoire des arts industriels au moyen âge… (2nd edn., Paris, 1875), iii, 133–6Google Scholar.

54 Madame Gauthier's list included no less than 52 objects either found in British soil or with a more or less early British provenance. She also cited several early references to Limoges enamels in pre-Dissolution church inventories. For two of the most interesting recent finds, see Blair, C. and Campbell, M. L., ‘An eleventh-century latten candlestick base and a thirteenth-century Limoges plaque from Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire’, Antiq. J. lix (1979). 414–18, pl. LxxmbGoogle Scholar; E. Baker, ‘The medieval travelling candlestick from Grove Priory, Bedfordshire. SP 923227’, Ibid., lxi (1981), 336-8.

55 BM. M&LA 1985, 5-i, 1-2. St John plaque: H. 3-5 cm., W. 5-9 cm.; bent convex; several losses of enamel; palette: azure-blue (ground), white, yellow, green, opaque red. Flowered plaque: H. 4-1 cm., W. 3-2 cm.; azure-blue (ground), turquoise (central stud). Gilding largely survives on both plaques.

56 cf. Thoby, P., Les Croix limousines de la fin du Xlle siécle au début du XlVe siecle (Paris, 1953), nos. 33 (pl. xx), 36 (pl. XXII)Google Scholar, for similar plaques on the reverse of complete Limoges crosses.

57 BM. M&LA 1985, 2-1,1. Diam. 46 cm.

58 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts EDA. 57.673 (gift of Mr and Mrs John Hunt in honour of Dr Georg Swarzenski). Diam. 4-4 cm.

59 The Boston plaque is to be included in vol. i of the Corpus des Émaux Méridionaux (forthcoming) as Cat. 144 (ill. 465): ‘Vers 1190, courant hispano-limousin.’ Closely related are also some of the plaques mounted on the Souvigny Bible book-cover in the late eighteenth century, for which see Gauthier, Marie-Madeleine, ‘Un style et ses lieux: les orne-ments me'talliques de la Bible de Souvigny’, Gesta, xx, 1 (1981) (Essays in honor of Harry Bober), 141–53CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 BM. M&LA 1985, 3-2,1. H. 14-6 cm., W. 28-5 cm.

61 On the back of the frame is also written: ‘Said by Mr Franks of the British Museum to be a Limoges Enamel of about the Date A.D. 1200.’ Franks was Keeper of British and Mediaeval Antiquities 1866-96.

62 See Knowles, D., Brooke, C N. L. and London, V. C. M. (eds.), The Heads of Religious Houses. England and Wales 940-1216 (Cambridge, 1972), 193Google Scholar, for the foundation of Bayham 1199/1208, by the amalgamation of the slightly earlier foundations of Brockley and Otham. For the early history of Bayham, see particularly Colvin, H. M., The White Canons in England (Oxford, 1951), 109–18, 395Google Scholar.

63 British Museum, loan. See Way, Albert, ‘Notices of an enamelled chalice, and of other ancient reliques, found on the site of Rusper Priory’, Sussex Arch. Coll. ix (1857), 303–11Google Scholar.

64 The classic article on this group remains J.-J. Marquet de Vasselot, ‘Les émaux limousins à fond vermiculé (Xlle et XHIe siècles)’ (extr. from Revue Arch. vi-Paris, 1906). See also Gauthier, M.-M., ‘Les décors vermiculés dans les émaux champlevés limousins et méridionaux. Aperçcus sur l'origine et la diffusion de ce motif au Xlle siécle’, Cahiers de Civ. Méd. 1958, 349–69Google Scholar.

65 For good illustrations of the Leningrad châsse, see Lapkovskaya, E. A., Applied Art of the Middle Ages in the Collection of the State Hermitage. Artistic Metalwork (Moscow, 1971), pls. 13–14Google Scholar. See also Gauthier, M.-M. S., ‘La légende de sainte Valérie et les émaux champleves de Limoges’ (extr. from Bull. Soc. Arch, et Hist, du Limousin, Ixxxvi (Limoges, 1955), 35–80)Google Scholar.

66 e.g. the celebrated Bateman-Astle châsse, for which see Caudron, S., ‘Connoisseurs of champlevé Limoges enamels in eighteenth-century England’, Collectors and Collections. The British Museum Year book 2 (1977), partic. pl. (6) on p. 16Google Scholar. Cf. also Vasselot, Marquet deop. cit., note 64), pl. v (top)Google Scholar: this châsse is now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (17.190.514-gift of J. Pierpont Morgan).

67 The celebrated châsse of Gimel, for example, combines in the same scene figures with separately cast heads and figures with heads enamelled in the copper surfaces: see Gauthier, M.-M., Émaux limousins champleves des Xlle, XIHe et XIVe siècles (Paris, 1950), pl. 9Google Scholar. For examples of appliqúe figures, see Ibid., pls. 17, 31, 33, 36, 39.

68 The authors are grateful to Mr Abramson, for information about their context and to Mr John Hedges, F.S.A., County Archaeologist, for obtaining permission to exhibit and publish the moulds here in advance of their full publication in Excavations at Castleford, by P. Abramson.

69 See , Allason-Jones and Miket, , op. cit. (note 37), 326 and 336Google Scholar; Colchester Castle Museum, no number.

70 See Guildhall Museum Catalogue, no. 1168; Yorkshire Museum, Dalton Terrace 1957 and no number; Malton Roman Museum, 30-448; Aldborough site Museum, AML nos. 78108157/8.

71 The authors wish to thank Mr J. Thorn for drawing the figures.

72 See Riha, E. and Stern, W. B., Die römischen Löffel aus Augst und Kaiseraugst (08, 1982), 25–6Google Scholar.

73 See S. Tassinari and Burkhalter, F., ‘Moules de Tartous…’, in Toreutik und figürliche Bronzen romischer Zeit, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz Berlin (1984), 97Google Scholar. We are grateful to Mr Donald Bailey, F.S.A., for this reference.

74 Riha, and Stern, , op. cit. (note 72), 27Google Scholar.

75 AML no. 786992; see Webster, G., Excavations at Wroxeter, forthcomingGoogle Scholar.

76 See Crummy, N., ‘The worked bone from Crowder Terrace’, Winchester Excavations, i, forthcomingGoogle Scholar; Pitt-Rivers, A. L., Excavations in Cranborne Chase (1887), 129–30, pl. XLVGoogle Scholar.

78 Details of the analytical technique are in Brownsword, R. and Pitt, E. E. H., ‘Alloy composition of some cast latten objects of the 15th/16th centuries’, Historical Metallurgy, xvii (1983), 44–9Google Scholar.

78 Oddy, W. A., ‘Gilding and tinning in Anglo-Saxon England’, in Oddy, W. A. (ed.), Aspects of Early Metallurgy, Historical Metallurgy Soc. and B. M. Research Laboratory (1977), 129–34Google Scholar.

79 Speake, G., Anglo-Saxon Animal Art and its Germanic Background (Oxford, 1980), fig. 3, h, and 8, jGoogle Scholar.

80 Ibid., fig. I,e.

81 Ibid., fig. 9.

82 Ibid., fig. 8, h.

83 Ibid., 65.

84 Ibid., 45.

85 Brownsword, R., Ciuffini, T. and Carey, R., ‘Metallurgical analyses of Anglo-Saxon jewellery from the Avon valley’, West Midlands Arch, xxvii (1984), 101–12Google Scholar.

86 Oddy, W. A., Bimson, M. and Niece, S. La, ‘The composition of niello decoration on gold, silver and bronze in the antique and mediaeval periods’, Studies in Conservation, xxviii (1983), 29–35Google Scholar.

87 Speake, , op. cit. (note 79), pl. 51, gGoogle Scholar.

88 Ibid., pl. 16, h.

89 Hawkes, S. C., ‘The Amherst brooch’, Arch. Cant, c (1984), 136–7, 140Google Scholar.

90 Speake, , op. cit. (note 79), pl. 11Google Scholar.

91 Wilson, D. M., Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700-1100 in the British Museum (London, 1964), no. 2Google Scholar.

92 Evison, V. I., ‘An Anglo-Saxon disc brooch from Northamptonshire’, Antiq. J. xlii (1962), 54Google Scholar; Speake, , op. cit. (note 79), pl. 15, bGoogle Scholar.

93 Vierck, H., ‘Eine angelsachsische Zierscheibe des 7 Jahrhunderts n. Chr. aus Haithabu’, Berichte iiber die Ausgrabungen in Haithabu, xii (Neumiinster, 1978), Abb. 6Google Scholar.

94 Becker, A., Franks Casket (Regensburg, 1973)Google Scholar.

95 Waterer, J. W., ‘Irish book-satchels or budgets’, Med. Arch, xii (1968), 70–82CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

96 e.g. the objects in the Swallowcliffe, Wilts., burial: Speake, , op. cit. (note 79), pl. 16Google Scholar, and the reconstruction of the bag in the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum.

97 e.g. fo. 26v: see Nordenfalk, C., Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting (London, 1977), pl. 19Google Scholar. We are grateful to Dr Janet Backhouse for this point, made at the Ballot meeting.

98 Bruce-Mitford, R., The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, ii: Arms, Armour and Regalia (London, 1978), 556–63Google Scholar; Speake, , op. cit. (note 79), 20Google Scholar.

99 Stevenson, R. B. K., ‘Further notes on the Hunterston and “Tara” brooches, Monymusk reliquary and Blackness bracelet’, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scotland, cxiii (1983), 469–71Google Scholar.

100 Department of Applied Physical Sciences, Coventry (Lanchester) Polytechnic.

101 Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton.

102 Information from John Wymer, Norfolk Archaeological Unit.

103 Analysis carried out by Duncan Hook of the British Museum Research Laboratory and quoted here by permission of Dr M. Tite, Keeper. The analysis was carried out by XRF of the surface only without cleaning and the result should be regarded as semi-quantitative.

104 Taylor, J. J., Bronze Age Goldwork ofthe British Isles (Cambridge, 1980), 61–2Google Scholar.

105 Information from Duncan Hook, B.M. Research Laboratory. Lang, J., Meeks, N. D. and Mclntyre, I. M., ‘The metallurgical examination of a Bronze Age gold tore from Shropshire’, J. Hist. Metallurgy Soc. xiv, 1 (1980), 17–20Google Scholar.

106 Eogan, G., ‘The associated finds of gold bar tores’, J. Royal Soc. Antiq. Ireland, xcvii, 2 (1967), 129–75Google Scholar.

107 Information from John Wymer.

108 Taylor, , op. cit. (note 104), 60–2Google Scholar.

109 British Museum EA 26289 (fragmentary) and EA 26290 (intact).

110 EA 26289 was found ‘among the dwellings in the north colonnade’, season 1893/4: E. Naville, in Egypt Exploration Fund (henceforth EEF), Archaeological Report 1893-4, 7; cf. id., The Temple of Deir el Bahari. Introductory Memoir (London, 1894), 19) id., The Temple of Deir el Bahari, vi (London, 1908), 12. For the general findspot, cf. the plan of the temple in EEF, Arch. Report 1893-4 (‘northern colonnade’). This is clearly the bead referred to by Hayes, W. C., Mitt, deutschen arch. Instituts, Abt. Kairo, xv (1957), 88 fGoogle Scholar. The precise findspot of EA 26290 is not recorded, though the bead is evidently that alluded to in EEF, Report of the Ninth Ordinary General Meeting 1894-3’, 19, and Naville, , Deir el Bahari, vi, 12Google Scholar.

111 The following parallels may be cited: (i) Merseyside County Museums, Liverpool, M 11568. Provenance unrecorded. Cf. Stobart, H., Egyptian Antiquities (Berlin, 1855), pl. 1Google Scholar; Wilkinson, J. G., The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians,3rd edn., ed. Birch, S. (London, 1878), ii, 141, n. 3 (‘of a black and white colour, … resembling glass, … supposed to be agate’)Google Scholar; Gatty, C. T., Catalogue of the Mayer Collection, i: The Egyptian Antiquities, 2nd edn. (Liverpool, 1879), 56 f., no. 358 (‘basalt with a small streak of quartz running through it’)Google Scholar; Sethe, K., Urkunden, iv: Urkunden der 18 Dynastie, ii (Leipzig, 1906), 381, 117Google Scholar: Porter, B., Moss, R. L. B. and Burney, E. W., Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings, ii: Theban Temples, 2nd edn. (Oxford, 1972), 353Google Scholar; Eaton-Krauss, M., in Brovarski, E., Doll, S. K. and Freed, R. E., Egypt's Golden Age (Boston, 1982), 169, no. 193, 308 (‘turquoise and dark blue glass’)Google Scholar, (ii) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, MMA 26.7.746. Formerly in the Car-narvon collection, provenance unrecorded. Cf. Hayes, W. C., The Scepter of Egypt, ii (New York, 1959) 105 (‘white amethyst’), (iii) Formerly in the collection of ‘Captain Henvey, R. N.’Google Scholar; present whereabouts unknown. ‘Found at Thebes’. Cf. Wilkinson, , op. cit. 141, no. 381, figs. 3-4 (‘the specific gravity…, 25. 23, is precisely the same as of crown glass now manufactured in England’—to which Birch adds (n. 3): ‘This bead has been recently examined by Professor Maskelyne, who considers it to be a kind of obsidian’)Google Scholar, (iv) ‘Im Handel’; present whereabouts unknown. Cf. Sethe, , op. cit. 381 (material not specified)Google Scholar.

112 For the attribution, cf. Sethe, , op. cit. (note in), 381Google Scholar.

113 Winlock, H. E., Proc. American Philosophical Soc. lxxi (1932), 325Google Scholar; Weinstein, J. M., Foundation Deposits in Ancient Egypt (Ann Arbor, 1973), 154 fGoogle Scholar.

114 cf. Arnold, D., in Helck, W. and Otto, E. (eds.), Lexikon der Agyptologie, i (Wiesbaden, 1975), 1017 ffGoogle Scholar.

115 Schulman, A. R., J. American Research Center in Egypt, viii (1969-1970), 29 ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar; cf. Meyer, C., Senen-mut. Eine prosopographische Untersuchung (Ham burg, 1982), 264 ffGoogle Scholar.

116 cf. the references cited in note 110 above.

117 The analysis was carried out by Dr I. C. Freestone of the British Museum Research Laboratory. Petrie, with characteristic flair, had recognized the true nature of one of the beads (presumably EA 26289) as early as 1896: ‘A clear white glass bead of Senmut was found at Deir el Bahri (1894)’ (A History of Egypt during the XVII th and XVIIIth Dynasties (London, 1896), 90)Google Scholar. To judge from a photograph kindly supplied by Dr P. F. Dorman, MMA. 26.7.746 (note in (ii) above) appears to have been fashioned from a similar material.

118 cf. Lucas, A., Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, 4th edn., rev. by Harris, J. R. (London, 1964), 190Google Scholar; Bimson, M., Annales du σe Congrès International d'Étude Historique du Verre (Liège, 1974), 291 ffGoogle Scholar.

119 British Museum EA 9558. This piece will be published fully elsewhere.

120 The sceptre head was discovered by Colin Marshall and Jack Marshall of Cleethorpes and is now in Scunthorpe Borough Museum (Inv. KMAA 508). The model swords were found by Alan Harrison of Winterton and remain in his possession. The writers gratefully acknowledge the assistance of these gentlemen in making the material available for study. The photographs of the sceptre head were very kindly provided by Robert Wilkins, F.S. A., at short notice; the drawings and the photographs of the sword by Kevin Leahy. Since county reorganization the site is in South Humberside.

121 Total height 66 mm.; height of head alone 35 mm. It is in very good condition apart from slight denting and corrosion on the right side, and a hole at the back (see below).

122 Stead, M., ‘The reconstruction of Iron Age buckets from Aylesford and Baldock’, in Sieveking, G. de G. (ed.), Prehistoric and Roman Studies (British Museum, London, 1971), 260–3, pls- LXXXIX, xcGoogle Scholar.

123 Corder, P. and Richmond, I. A., ‘A Romano-British interment, with bucket and sceptres, from Brough, East Yorkshire’, Antiq. J. xviii (1938), 68–74CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

124 Ibid., 73-4.

125 Henig, M. and Leahy, K., ‘A bronze bust from Ludford Magna, Lincolnshire’, Antiq. J. lxiv (1984), 387–9Google Scholar.

126 Length 49 mm.; maximum width 8 mm.; thickness 0-4 mm.

127 Length 42 mm.; hand and arm 25 mm. The hole is 3 mm. in diameter.

128 See Bradford, J. S. P. and Goodchild, R. G., ‘Excavations at Frilford, Berks., 1937-8’, Oxonien-sia, iv (1939), 13 and pl. vbGoogle Scholar; cf. Fauduet, I., ‘Miniature “ex-voto” from Argentomagus (Indre)’, Britannia, xiv (1983), 97–102CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

129 Leahy, K. A., ‘Votive models from Kirmington, South Humberside’, Britannia, xi (1980), 326–30CrossRefGoogle Scholar. More recent discoveries from the general area where the sceptre head was found include two votive ‘thumb pots’ and a number of cremation burials. A group of brooches found in the area would suggest activity in the vicinity during the first and second centuries A.D.

130 Ambrose, T. and Henig, M., ‘A new Roman rider-relief from Stragglethorpe, Lincolnshire’, Britannia, xi (1980), 135–8CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

131 Riley, D. N., ‘Roman defended sites at Kir-mington, South Humberside and Farnsfield, Notts., recently found from the air’, Britannia, viii (1977), 189–92, figs. 1 and 2, pl. xivCrossRefGoogle Scholar; Joseph, J. K. St, ‘Air reconnaissance in Roman Britain 1973-6’, J-R-S. lxvii (1977), 158–9, pl. xvi, 2Google Scholar.

132 Whitwell, J. B., The Coritani, B.A.R. 99 (Oxford, 1982), 43Google Scholar.

133 Whitaker, T. D., History of Whalley (London, 1801), 27–8Google Scholar; reg. no. P1983. 10-1.1.

134 Watkins, W. T., Roman Lancashire (1883), 212–13Google Scholar; Macdonald, G., ‘Notes on some fragments of imperial statues,’ J.R.S. xvi (1926), 9–16Google Scholar; Collingwood, R. G. and Wright, R. P., Roman Inscriptions of Britain (Oxford, 1926), no. 582Google Scholar.

135 The arm is 224 cm. in length and 1525 g. in weight; the plaque measures 4-2x2-5 cm. and is 4-3 g. in weight; the ring-band is 12-1 g. in weight.

136 By Dr M. J. Hughes and Dr M. S. Tite, to whom we are indebted; a full report is on file (Research Laboratory file 4288).

137 Fleischer, R., Die romischen Bronzen aus Oster-reich (Mainz, 1967), no. 119Google Scholar.

138 Ibid., nos. 121, 122.

139 Menzel, H., Die romischen Bronzen aus Deutsch-land, ii: Trier (Mainz, 1967), no. 71Google Scholar.

140 Jitta, A. N. Zadoks-Josephus, Peters, W. J. T. and Es, W. A. van, Roman Bronze Statuettesfrom the Netherlands (Groningen, 1969), no. 62Google Scholar.

141 Op. cit. (note 134), n.

142 Holder, P. A., The Roman Army in Britain (London, 1982), 105Google Scholar.

143 This title was given by Hayes, J. W. in his discussion of Egyptian Red Slip Wares in Late Roman Pottery (London, 1972)Google Scholar and its Supplement (London, 1980)Google Scholar. The first large group to be published appeared in Winlock, H. E. and Crum, W. E., The Monastery of Epiphanius at Thebes (New York, 1926), 85–7, pls. XXXI-XXXIIGoogle Scholar.

144 For examples of this ware, see Hayes, , op. cit. (note 143), 387–97Google Scholar, and Supplement, 530-2; Rodziewicz, M., Alexandrie, i: La Céramique romaine tardive d'Alexandrie (Warsaw, 1976)Google Scholar, Groups O and W; Guerrini, L., in Donadoni, S., Antinoe 1965-1968 (Rome, 1974), 70–81Google Scholar; Egloff, M., Kellia, iii: La Poterie copte (Geneva, 1977), Group 1Google Scholar; Johnson, B., Pottery from Karanis (Ann Arbor, 1981), 1-2, 19–23Google Scholar; Haynes, J., in J. American Research Center in Egypt, xviii (1981), 19–26Google Scholar; Bailey, D. M., in Spencer, A. J.et al., Ashmunein (1982) (London, 1983), 27–36Google Scholar, Ashmunein (1983) (London, 1984), 18–20Google Scholar, Ashmunein (1984) (London, 1985), 26–7, 34Google Scholar.

145 Cyprus and Carthage: Hayes, , op. cit. (note 143), 397Google Scholar, and Supplement, 531, nn. 1-2. Cyrenaica: Hayes, , op. cit. (note 143)Google Scholar and Kenrick, P., Excavations at Sidi Khrebish, Benghazi (Berenice), iii, 1 (Tripoli, 1985), 402–3Google Scholar.

146 Adams, W. Y., in Dinkier, E. (ed.), Kunst und Geschichte Nubiens in christlicher Zeit (Recklinghausen, 1970), 118–20Google Scholar.

147 Hayes, , op. cit. (note 143)Google Scholar, Supplement, 530; Hayes, J. W., Roman Pottery in the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, 1976), 24Google Scholar.

148 Ulbert, T., in Mitt, deutschen arch. Instituts, Abt. Kairo, xxvii (1971), 235–42, pl. LXIVGoogle Scholar.

149 Hayes, , op. cit. (note 143), 128–33Google Scholar.

150 For example, Egloff, , op. cit. (note 144), Type 33Google Scholar.

151 Johnson, , op. cit. (note 144), 2Google Scholar.

152 J. Egyptian Arch. lxx (1984). 186Google Scholar.

153 Winlock, and Crum, , op. cit. (note 143), pl. XXXIIBGoogle Scholar.

154 Spencer, A. J.et al., Ashumunein (1983) (London, 1984), 19Google Scholar.

155 Ulbert, , op. cit. (note 148), 235, 241Google Scholar.

156 Kolodziejczyk, K. in Etudes et Travaux, xiii (1983), 193–201Google Scholar.

157 For decorated examples, see the many found at Elephantine described by Gempeler, R. in Mitt, deutschen arch. Institute, Abt. Kairo. xxxii (1976), 108, rig. 8a, and p. 109Google Scholar.

158 The poingon is reg. no. 1864.9-15.5 (serial no. 38410); L. 4-5 cm., W. 3 cm. The mould fragment is reg. no. 1876.6-15.39 (serial no. 37637); H. 8-3 cm., W. 8-6 cm.

159 Reg. no. 1907.1-12.20 (serial no. 43417). From the collection of Robert de Rustafjaell (1876-1943), collector, author and romantic; H. 9 cm., W. 8-8 cm.

160 I am grateful to the Revd Mark Spurrell, Rector of St Mary's, Stow-in-Lindsey, Lincolnshire, for calling the ship graffito to my attention (1985). For Stow church, see Spurrell, M., Stow Church Restored 1846-1866, Lines. Record Soc. lxxv (1984)Google Scholar; Sir Clapham, A., ‘Lincolnshire priories, abbeys, and parish churches’, Arch. J. ciii (1947), 168–73Google Scholar; V.C.H., Lincolnshire, ii, 118Google Scholar.

161 The hulc-type ship graffito at St Albans Abbey (of which only fragments now remain) is of possible Celtic origin, and the oldest known drawing of a post-Roman vessel in England. Jones-Baker, D., ‘The graffiti of English medieval and post-medieval ships: a source for nautical archaeology’, a paper read to the Society of Antiquaries, 2nd 02, 1984-for an expanded versionGoogle Scholar, see The Graffiti of English Medieval and Post-Medieval Ships, forthcoming.

162 The research problems arising from the lack of pictorial evidence for early English ships are set out by Anderson, R. C., Oared Fighting Ships (Kings Langley, 1976), pp. vi, 42–51Google Scholar. For the limitations of accounts and other documentary sources, see Rose, S., The Navy of the Lancastrian Kings. Accounts and Inventories of William Soper, Keeper of the King's Ships 1422-1427 (Navy Records Soc., 1982), 40–1Google Scholar.

163 There is a drawing of this graffito in Landstrom, B., The Ship (London, 1961), 57, and fig. 141Google Scholar.

164 Ibid., 62.

165 See Christensen, A. E., ‘Viking Age rigging, a survey of sources and theories’, in McGrail, S. (ed.), Medieval Ships and Harbours in Northern Europe, B.A.R. S66 (Oxford, 1979), 183–93Google Scholar.

166 By the ninth century the Vikings had evolved a rudder which was dissimilar to the ordinary oar. That on the Gokstad ship is more like a paddle than an oar. It is fixed almost vertically in the water, and i s manoeuvred by a thin handle affixed to it at right-angles. By pressing in the handle the boat was turned to the right, by lifting it the boat turned to the left. In the Viking longships this quarter rudder, as it is termed, was invariably on the starboard side, and retained this position as long as it was in use. The ships on the Bayeux Tapestry are all steered in this fashion, although the steering oars shown are not of the same shape as that of the Gokstad ship. Brooks, F. W., The English Naval Forces 1199-1272 (London, 1932), 10Google Scholar.

167 Anderson, , op. cit. (note 162), 42–3Google Scholar. Tinniswood, J. J., ‘English Galleys, 1272-1377’, in The Mariner's Mirror (1949)Google Scholar, sets out the manuscript and printed sources that begin at the end of the thirteenth century.

168 Landstrom, , op. cit. (note 163), 61Google Scholar.

169 Jones-Baker, D., ‘Graffito of medieval music in the Tresaunt, Windsor Castle’, Antiq. J. lxiv (1984), 375Google Scholar.

170 These arguments are reviewed by Spurrell, M., op. cit. (note 160)Google Scholar, and Saint Mary Stow in Lindsey (Lincoln, 1982), 2–3Google Scholar; and by Hill, J. M. F. in Medieval Lincoln (Cambridge, 1948), 74–7Google Scholar.

171 The medieval chronicler Florence of Worcester, d.1118 (Chronicon), says that the church at Stow was built by Bishop Eadnoth, but, as pointed out by Dr Salter, (Cartulary of Eynsham (Oxon.), i, p. x)Google Scholar, the charter of Leofric which mentions the food rent that Aethelric (1017-34) had enjoyed indicates that the re-founder of this church might well have been Eadnoth I (1006-16) rather than Eadnoth II. On the basis of the documentary evidence, Hill, J. M. F. took this view (op. cit. (note 170), 74–5)Google Scholar. The ship graffiti were cut on the earlier stonework of Aelfnoth's church, and the lower part of this pier in the crossing appears to have been left undisturbed at the rebuilding after the fire.

172 Salter, , op. cit. (note 171), i, 28Google Scholar; Robertson, A. J. (ed.), Anglo-Saxon Charters (Cambridge, 1939), 213Google Scholar.

173 For early ship graffiti: at Urnes, Fortun, and Kaupanger on Sognefjord, see Blindheim, M., Graffiti in Norwegian Stave Churches c. 1150-1350 (Oslo, 1985), 57, pls. xxxiv, nos. 3–5, LII, no. 5, LXIX, no. 4Google Scholar. Viking ship graffiti at Kirk Maughold, Isle of Man, in Ireland, and Scotland are described by Johnstone, P., ‘The Bantry Boat’, Antiquity, xxx-viii (1964), 277–84, and pl. XLVIIICrossRefGoogle Scholar. The one-masted ship graffito at Dunluce Castle, Co. Antrim, Ireland, is illustrated in A. W. Farrell, ‘The use of iconographic material in medieval ship archaeology’, in McGrail, , op. cit. (note 165), 231Google Scholar. Although no examples are given from England, the use of ancient graffiti as a source for the history of ship architecture by Landstrom, B. (op. cit. (note 163))Google Scholar is a model of its kind, particularly for the Viking and pre-Viking period in Scandinavia.