page 93 note 1 Collingwood, R. G. and Richmond, I. A., The Archaeology of Roman Britain (Methuen, 1969).Google Scholar

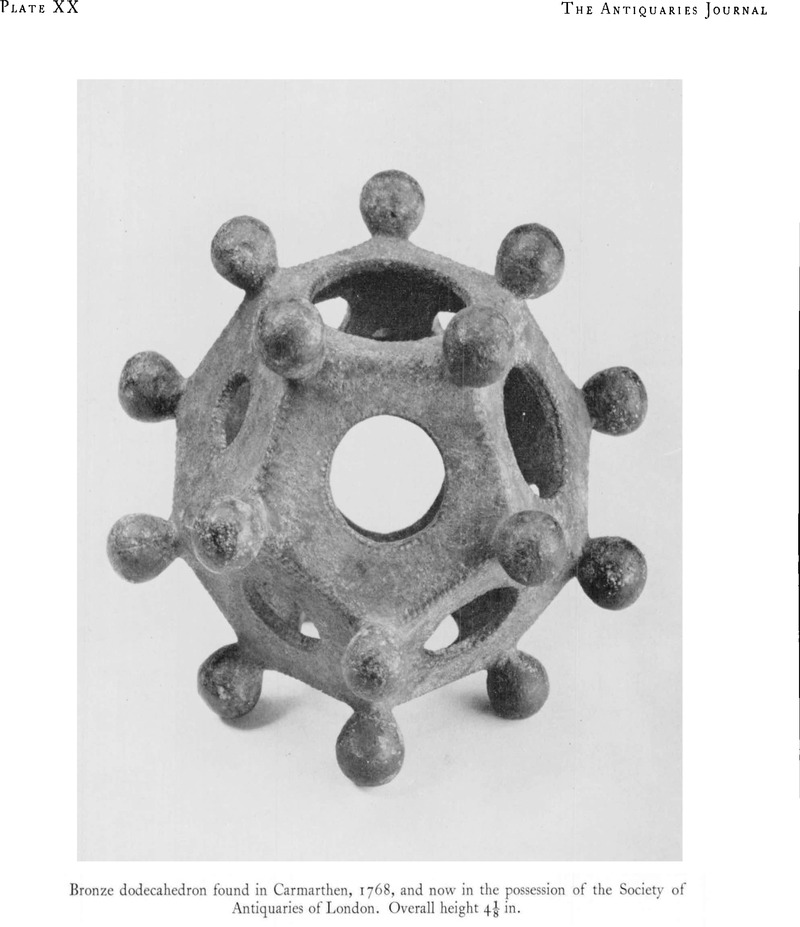

page 93 note 2 J. de Saint-Venant listed forty-one in his factually brilliant but deductively erratic study, Dodécaèdres perlés en bronze creux ajouré de l'époque gallo-romaine (Nevers, 1907), with the caveat that some early discoveries might have been counted twice; further examples, missed by St.-Venant or excavated subsequently, bring the number to around 50.Google Scholar

page 93 note 3 The largest seems to be that from Fishguard in the British Museum; cf. Antiq. Journ. iv (1924), 273.Google Scholar

page 93 note 4 And so well within the Roman town area as defined by Jones, G. D. B. (Carmarthen Antiquary, v (1964–1969), pl. opposite p. 2).Google Scholar

page 93 note 5 S.A. Mins. xvii (1780–1), 98; curiously, one found at Aston, Herts., in 1739 and exhibited to the Society in that year (Mins. iii (1739), 22 3), seems to be the first recorded example, but it is now lost.

page 93 note 6 The Archaeology of Roman Britain (1930), p. 274 and fig. 67b.

page 93 note 7 London in Roman Times (London Museum Catalogue no. 3), pp. 110–11 and fig. 35; the list is based on St.-Venant, op. cit., pp. 21–32, but omits the suggestion that they held sponges and were used as sprinklers (ibid., p. 22)!

page 93 note 8 Op. cit., in n. 1, p. 316 and pl. XXId.

page 93 note 9 Ibid., p. 324.

page 93 note 10 p. 14: K. Mauel, Der ‘Theodolit’ des römischen Feldmessers.

page 93 note 11 ‘Das Pentagondodekaeder des Museum Carnuntinum und seine Zweckbestimmung’, Carnuntum Jahrbuch, 1956 (1957), 23–9.

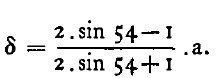

page 95 note 1 Using Kurzweil's formula

page 95 note 2 I am indebted to my daughter for assistance in the calculation of b.

page 95 note 3 Cf. Vegetius, De re militari, iii, 8, referring to the use of 10-foot poles (decempedae) by centurions in checking defence measurements.

page 95 note 4 Westdeutscher Zeitschrift, xi (1892), 209.Google Scholar

page 95 note 5 O.R.L. xxv (1905), 22–3.Google Scholar

page 95 note 6 O.R.L. xxxii (1909), 94, discussing a fragment from ZugmantelGoogle Scholar; Loeschcke, S., ‘Lampen aus Vindonissa’ (Mitteilungen der antiquarisches Gesellschaft in Zürich, xxvii (1919)), p. 353 (165) and Taf. XXIII, 1091.Google Scholar

page 95 note 7 Trans. Carmarthens. Antiq. Soc. and Fd. Club, xvii (1924), 30–2Google Scholar, following ibid, xvi (1923), 57.

page 95 note 8 p. 93, n. 1.

page 95 note 9 London in Roman Times, fig. 35, 2.

page 96 note 1 Coulon, Raimond, Essai de reconstitution des dodécaèdres creux, ajourés et perlés attribués à l'époque gallo-romaine (Rouen 1910), pp. 252–6.Google Scholar

page 96 note 2 And later in Renaissance science and art. Cf. the analysis by Filippo Magi of the two Laocoon frescoes in the villa near Cortona, built for Cardinal Passerini by Giovanni Battista Caporali in 1521–7 (Atti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia: Rendiconti, xl (1967–1968), 275–94). One fresco shows a hollow dodecahedron in one corner which Magi describes as ‘un pezzo di bravura’ by the artist. He compares it with the solid dodecahe dron in the picture by Jacopo de’ Barbari, where Luca Pacioli is explaining a mathematical problem to Guidobaldi I of Urbino, and with the two dodecahedrons, solid (duodecedron planus solidus) and hollow (duodecedron planus vacuus) depicted by the same Luca in the manuscript De divina proportione.Google Scholar