Introduction

Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae Hombron & Jacquinot) are among the best-studied seabirds anywhere on the planet, having been the subject of research for more than 100 years (beginning with J. Murray in Shackleton Reference Shackleton1909; otherwise summarized in Ainley Reference Ainley2002, Borboroglu & Boersma Reference Borboroglu and Boersma2015). Typical of Antarctic seabirds, Adélie penguins live in colonies (ranging from a few dozen breeding pairs to hundreds of thousands, depending on how colonies are defined; Ainley et al. Reference Ainley, Nur and Woehler1995, Reference Ainley2002), forage primarily on krill (Euphausia spp.) and fish (especially Pleuragramma antarcticum Boulenger) and, unless there are unusual circumstances (e.g. Dugger et al. Reference Dugger, Ainley, Lyver, Barton and Ballard2010, Reference Dugger, Ballard, Ainley, Lyver and Schine2014, LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Ainley, Swanson, Lyver, Dugger, Ballard and Barton2013), they tend to exhibit high levels of philopatry, with most returning to within 100 m of where they hatched (Ainley Reference Ainley2002). Across Antarctica, breeding populations of Adélie penguins are relatively clustered, and they typically select nesting locations on the few areas of ice-free land with access to the small rocks they use to construct their nests (Ainley et al. Reference Ainley, Nur and Woehler1995, Ainley Reference Ainley2002). The two eggs laid per clutch by Adélie penguins rest directly on the pebbles, upon which incubation temperatures are achieved by brooding parents as the eggs are kept away from the cooling and wetting potential of snow and ice (Ainley Reference Ainley2002). In fact, because of these well-known and predictable traits within their life history, it is now possible to assess population presence and size remotely. Guano stains are reliable indicators of colony presence (but see Southwell et al. Reference Southwell, Emmerson, Takahashi, Kato, Barbraud, Delord and Weimerskirch2017), and the size of the guano stain is positively correlated with breeding population size (Schwaller et al. Reference Schwaller, Southwell and Emmerson2013, LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Lynch, Lyver, Barton, Ainley and Pollard2014b, Lynch & LaRue Reference Lynch and LaRue2014). The Adélie penguin is considered an ‘indicator’ or ‘sentinel’ species (www.ccamlr.org/en/science/ccamlr-ecosystem-monitoring-program-cemp). Thus, there has been a substantial research investment in learning about the Adélie penguin presence, absence and population size across Antarctica using remote sensing as a tool to search exclusively on ice-free land where colonies are known to nest.

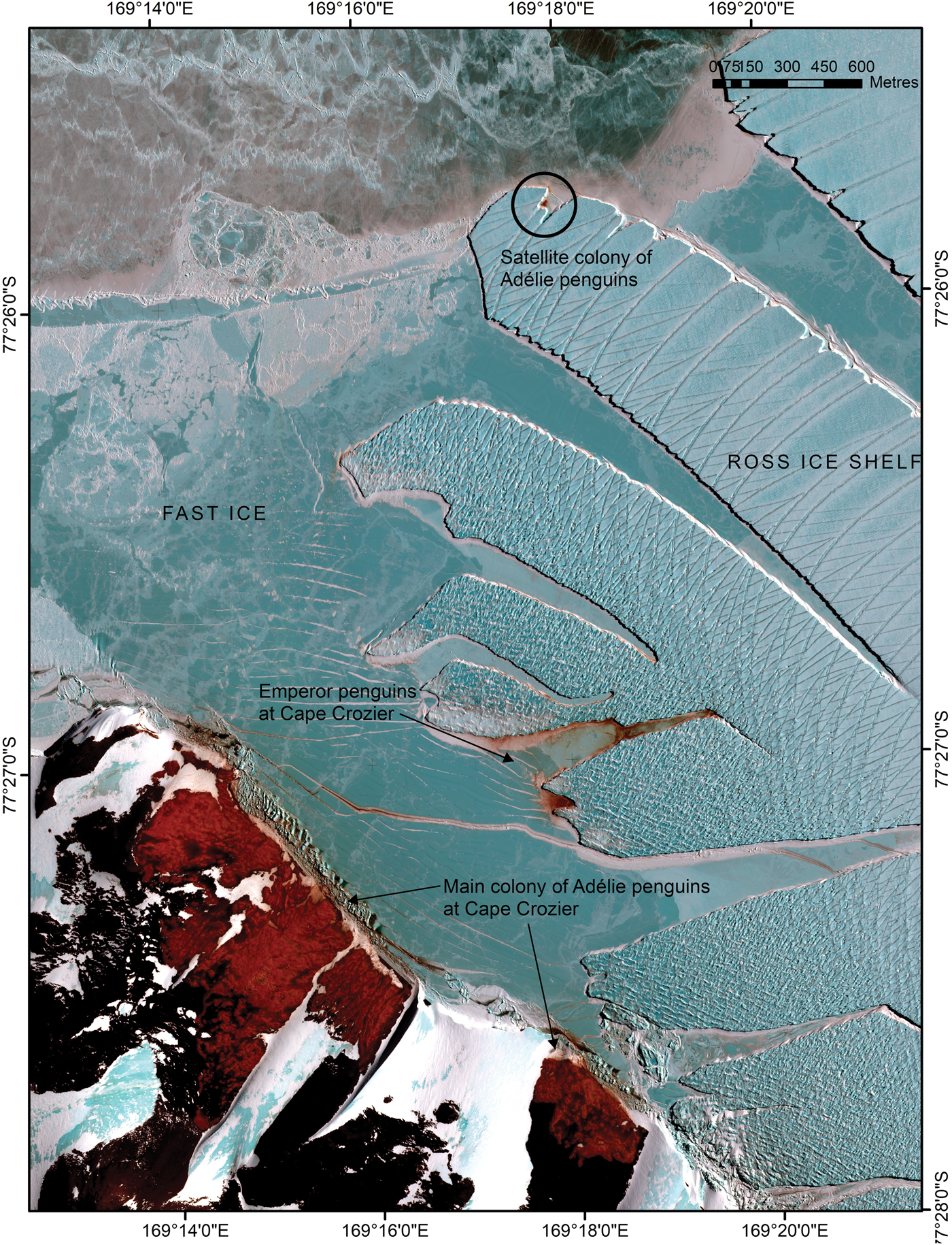

Here, documentation is provided from aerial photography and high-resolution satellite imagery (VHR) of Adélie penguins apparently attempting to nest on fast ice or a submerged portion of the Ross Ice Shelf off the coast of Cape Crozier, where one of the largest Adélie penguin colonies exists. Our observations during spring 2018 were opportunistic, as part of aerial flights intended to document emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri Gray) colony size, location and habitat characteristics in the Ross Sea. Our field observations indicate that Adélie penguins can engage in mating or nesting behaviours on fast ice, contrary to the current state of knowledge on these behaviours for the species as happening only on ice-free land. Besides adding information about the Adélie penguin life history, this phenomenon may affect survey techniques and related population estimates of emperor penguins because the presence of guano stains on fast ice has previously been associated exclusively with emperor penguins (Fretwell et al. Reference Fretwell, LaRue, Kooyman, Wienecke, Porter, Fox and Fleming2012). The fact that Adélie penguins may occasionally aggregate on fast ice during spring is also important for future emperor penguin surveys via VHR.

Methods

We flew by helicopter over the fast ice offshore of Cape Crozier Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) No. 124 to photograph the emperor penguin colony on 9 November 2018. As the area was surveyed, recording landscape features (e.g. fast ice extent, age, annual or multiyear, presence of other animals), a guano stain was noticed several kilometres away and closer to the fast ice edge (Figs 1 & 2). Upon closer inspection, suspecting it was a smaller group of emperor penguins we had not previously documented, because small and ephemeral satellite colonies of emperor penguins have been recorded elsewhere in the Ross Sea (e.g. Cape Colbeck; LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Kooyman, Lynch and Fretwell2014a), a group of Adélie penguins were found. The birds were photographed using 400 mm telephoto lenses at this location on three occasions (9, 13 and 15 November 2018), as well as the surrounding landscape, and subsequently counted the number of individuals on the photographs from 9 November. We then reviewed VHR (via DigitalGlobe, Inc.) to determine whether the guano stain was detectable from the images and to verify the location and timing of arrival.

Fig. 1. Location of ‘satellite’ (sub-)colony of Adélie penguins ~3 km from the main colony on land at Cape Crozier, Ross Island, Antarctica, on 24 November 2018, ~9 days after the last photos were captured from helicopter flight. WorldView-02 image courtesy of DigitalGlobe, Inc. (catalogue ID: 1030010088A89A00).

Fig. 2. Adélie penguins apparently ‘nesting’ on the fast ice off the coast of the Cape Crozier colony on 9 November 2018, the date of initial discovery. Photo credit: Sara Labrousse, with a 400 mm zoom lens.

Results

We counted 426 Adélie penguins engaging in what appeared to be nesting: behaviours of pair formation, spacing similar to a normal nest distribution and lying in divots in the ice that looked like nests. It essentially appeared to be a sub-colony of the main Crozier Adélie penguin colony, which was ~3000 m away. It was noted that the colour of the guano was consistent with birds foraging for krill (i.e. bright red) and that the group was apparently using a crack in the ice near the end of the Ross Ice Shelf to enter the water (rather than the edge of the fast ice). Eggs were not seen from our vantage point in the helicopter, though we were probably too far away to see them if they were there, even with our zoom lenses (400 mm telephoto lenses; Figs 2 & 3) and binoculars (×8 zoom).

Fig. 3. Adélie penguins on the fast ice off the coast of the Cape Crozier colony on the last day of observations, 15 November 2018. Photo credit: Sara Labrousse, with a 400 mm zoom lens.

The same group of Adélie penguins were observed on 13 and 15 November, again as we gathered aerial photographs of the emperor penguin colony and recorded landscape features (Fig. 3). It was noted that, since our first visit, the ice extent had changed substantially, with the pack ice blowing in and out as a function of wind direction and tidal currents. On 15 November in particular, it was noted that the guano stain associated with the Adélie penguins on the fast ice had changed from red to green, an indication that the birds were fasting.

A subsequent search of VHR (~0.5 m spatial resolution) provided by DigitalGlobe, Inc., indicated that the birds arrived at the site on or before 30 October (catalogue ID: 1030010085721F00), as the guano stain was apparent on the image. This timing was consistent with the arrival of Adélie penguins at the normal Crozier colony where another study was underway (Lescröel et al., personal communication 2018). The birds were still present at their location 1 December (WorldView-04 image ID f9bf0107-d6df-4f30-9479-36c76b23969e-inv). However, there was a storm on 3 December, and it seems that the colony was lost. The fate of the individual birds is not known; the fast ice was effectively gone by 4 December and remained that way through 12 December as confirmed by VHR (catalogue ID: 1040010045C93C00) and 19 December, as confirmed by helicopter. Thus, this satellite sub-colony existed for at least one month in spring 2018.

Discussion

For the first time, evidence is provided of Adélie penguins forming an apparent breeding sub-colony for an extended period on sea ice habitat and an appreciable distance from normally occupied terrain. We were most struck by the regular spacing of the birds, being similar to an actual nesting sub-colony (Adélie territories usually average ~0.67 m2, just pecking distance between neighbours; LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Lynch, Lyver, Barton, Ainley and Pollard2014b), rather than the spacing of foraging or resting flocks (Ainley Reference Ainley1972). From their location, the actual Crozier colony was not visible, shielded by height of the Ice Shelf (~30 m). Whether this observation is singular in its occurrence or more common than previously thought remains to be seen, but the implications are threefold. First, this is a somewhat cautionary (and certainly notable) observation; perhaps future work should pay closer attention to the surrounding landscape in locations near known Adélie colonies to see if this or similar behaviours are observed elsewhere. Second, our observations have important implications for synoptic VHR surveys of both Adélie but especially emperor penguins, specifically regarding the assumption that guano stains on fast ice or ice shelves represent only the presence of emperor penguins (Fretwell et al. Reference Fretwell, LaRue, Kooyman, Wienecke, Porter, Fox and Fleming2012, Reference Fretwell, Trathan, Wienecke and Kooyman2014). Clearly, at least in this one case, this assumption is not true. Most problematic is the fact that the guano stain is clearly visible on the VHR image (Fig. 1) and that most locations of emperor penguins around the continent are inaccessible for ground validation (LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Kooyman, Lynch and Fretwell2014a). Had we not confirmed the guano stain as belonging to Adélie penguins, review of VHR for emperor penguin research may have incorrectly identified this ‘satellite’ location as an emperor penguin colony. Therefore, our observation justifies regular ground validation to ensure appropriate interpretation of VHR results as they pertain to seabird ecology in Antarctica. Finally, should our observation represent a response to enigmatic atmospheric or climate changes, it is imperative that it is documented; broadly speaking, there is a need to identify which species will respond, adapt or display plastic behaviour and which species will fail with respect to our changing climate (Pettorelli Reference Pettorelli2012).

The most important and interesting implications of our observation are with regard to the biology of the Adélie penguin. We found only one article that previously reported similar findings to ours. Splettstoesser & Todd (Reference Splettstoesser and Todd1999) observed Adélie penguins in the Weddell Sea using emperor penguin stomach stones as nest pebbles and ‘nesting’ on the fast ice within the emperor penguin colony at Dawson-Lambton. However, this observation did not report the number of birds, nor the length of time over which the behaviour took place, though photographs within the literature indicate only a few individuals were observed. Communication among authors revealed that in the past at Cape Crozier, Adélie penguins ‘nested’ out from the colony on the fast ice using ice chunks as nest ‘stones’. This occurred in November 2002 when the colony was mostly cut off from the sea, with just a few avenues between large grounded icebergs, during the B-15 mega-iceberg event (Dugger et al. Reference Dugger, Ballard, Ainley, Lyver and Schine2014; Fig. 4). They were there only for a few days. In the situation described here, Adélie penguins actually formed a sub-colony that lasted for more than a month, obscured from the main colony by the Ross Ice Shelf, but directly out from where they should have been if they had been among the Crozier colony.

Fig. 4. Adélie penguins on the fast ice close to the Cape Crozier colony in spring 2002. Note the lack of evenly spaced nests and the high proportion of loafing penguins. Photo credit: Ben Saenz.

The life history of Adélie penguins is characterized by high natal and even higher breeding philopatry with normally low phenotypic plasticity (Ainley Reference Ainley2002), unless unusual circumstances such as the B-15 ‘natural experiment’ intercede (Shepherd et al. Reference Shepherd, Millar, Ballard, Ainley, Wilson and Haynes2005, Dugger et al. Reference Dugger, Ainley, Lyver, Barton and Ballard2010, Reference Dugger, Ballard, Ainley, Lyver and Schine2014). It is possible that the penguins involved in what we describe ‘knew’ that they had returned to their source colony, but for some reason failed to move sufficiently around the Ross Ice Shelf tongue that was obstructing the view of the colony from the sea to where the other ~280 000 pairs were lodged (see Lyver et al. 2014, for a colony count). In light of these facts, we posit several hypotheses as to why this group of Adélie penguins might have engaged in nesting behaviour on the fast ice, separate from a very large, nearby breeding colony:

1) Juvenile birds, mostly males, ‘practicing’ mating and nesting behaviours and in this case forming some sort of ‘critical mass’ that appeared to others to be a nesting group, regardless of the fact that the habitat was not appropriate.

2) Individuals becoming disoriented or confused on the way to the main colony. Indeed, the ice tongues that protrude from the Ice Shelf at Cape Crozier are continually growing and breaking off. Therefore, it is a land-/icescape that is particularly dynamic and changing, becoming more so as ice flow accelerates in the current era (Keys et al. Reference Keys, Jacobs and Brigham1994, Reference Keys, Jacobs and Brigham1998); the Ice Shelf in 2018 extended westward across the main Adélie colony more than at any time since the current authors have been conducting their research there (1996–present).

3) Nesting overflow from Cape Crozier, a colony that has been growing rapidly since 2010 (Lyver et al. 2014), has encouraged the founding of new sub-colonies, such as the colonization of north-eastern Beaufort Island in the 2000s (LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Ainley, Swanson, Lyver, Dugger, Ballard and Barton2013).

4) Possibly, our observation here represents a fluke incident with limited, if any, implications for the life history of the species.

It seems that, in a few cases, Adélie penguins have shown plasticity in their breeding behaviours by attempting to nest in suboptimal habitats. Interestingly, recent observations from VHR of emperor penguins have also suggested similar plasticity, as researchers observed apparent emigration (LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Kooyman, Lynch and Fretwell2014a), and also relocation to ice shelves and continental ice (Fretwell et al. Reference Fretwell, Trathan, Wienecke and Kooyman2014) in years when sea ice quality was poor. We did not note any unusual activity in the main Adélie nesting colony at Cape Crozier, other than continued expansion especially to terrain that is immediately adjacent to the beach as opposed to the upslope farther inland. Further documentation and study of this behaviour is needed in order to better understand its cause, prevalence and potential biological significance.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Science Foundation for funding (grant numbers PLR 1543498, 1543541 and 1744989), the US Antarctic Program for logistical support and DigitalGlobe, Inc., for satellite imagery. Further funding was provided by the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, University of Minnesota, University of Canterbury and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Overflights of ASPA No. 124 were taken under Antarctic Conservation Act permit #2019-006. We also thank H. Lynch and anonymous reviewers who provided feedback on previous drafts of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Field observations, notes and metadata made by all authors; quantifying bird counts and figure creation by MAL; manuscript written and revised by all authors.