Introduction

Ireland's links to the south polar region date back, at least, to the 1820s, when Edward Bransfield, from County Cork, recorded the first sighting of Antarctica, considered by some to be the last great wilderness on the planet (Neumann Reference Neumann, Tanaka, Johnstone and Ulfbeck2024). The region is home to a unique biodiversity, selected by the extreme characteristics of the marine and terrestrial environments (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Chown, Clarke, Barnes, Bokhorst and Cummings2014). However, despite its isolation, Antarctica is vulnerable to local human impacts, such as pollution, habitat destruction, wildlife disturbance and displacement and non-native species introductions (Tin et al. Reference Tin, Fleming, Hughes, Ainley, Convey and Moreno2009). Furthermore, human-induced climate change is being recorded across the continent. Impacts include ocean warming and acidification, glacier retreat, ice-shelf collapse, increased iceberg scouring of benthic habitats, a southwards shift in species distribution and exposure of new ice-free ground (Convey & Peck Reference Convey and Peck2019, IPCC Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Tignor and Poloczanska2019, Siegert et al. Reference Siegert, Atkinson, Banwell, Brandon, Convey and Davies2019, Clem et al. Reference Clem, Fogt, Turner, Lintner, Marshall, Miller and Renwick2020). Antarctica is also a key component of the Earth system, and events in Antarctica have the potential to influence what happens in other parts of the world. For example, climate change-induced ocean warming and associated ice-sheet instability have the potential to affect sea levels globally, with potentially catastrophic impacts upon human populations in low-lying and coastal regions, including around Ireland (Seigert et al. Reference Siegert, Bentley, Atkinson, Bracegirdle, Convey and Davies2023). It is against this backdrop that Ireland finds itself as a non-signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, having substantial interest in yet no influence over the governance of the region.

Antarctic geopolitics

Antarctica, despite its designation as a continent for peace and science, is still influenced by global geopolitics (Dodds & Raspotnik Reference Dodds and Raspotnik2023). World events, including the war in Ukraine and China's more robust foreign policy stance, have intensified national rivalries in Antarctica (Black et al. Reference Black, Sacks, Dortmans, Yeung, Savitz and Stephenson2023, Boulègue Reference Boulègue2023, Johnstone Reference Johnstone2023). To protect their resource and/or territorial interests, Parties such as Australia, China, New Zealand, the USA and the UK have invested in the strategic construction or upgrading of infrastructure, including research stations and ships (Harrington Reference Harrington, Tripathi, Bhadouria, Singh, Srivastava and Devi2024). Regulation of access to Antarctica's marine living resources is also a cause of tension, with China and Russia repeatedly blocking the designation of new marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean to protect their fishing interests (Boulègue Reference Boulègue2023). Contrary to the ban on mineral resource activities set out in the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, a Russian state-owned company, Rosgeologia, has undertaken seismic surveying of the Antarctic continental shelf, leading to fears that the Protocol may be at risk (Watson Reference Watkins2020, Afanaslev & Esau Reference Afanasiev and Esau2023, Jardine & Clack Reference Jardine, Clack, Clack, Meral and Selisny2023). Through the Treaty, Antarctica has been designated as a demilitarized zone, but there are concerns that Antarctic infrastructure could have dual uses (i.e. civilian/scientific and military). For example, ground stations for global satellite navigation systems could also be used for the control of military satellites or for missile guidance (McGee Reference McGee2023, Runde & Ziemer Reference Runde and Ziemer2023). Levels of Antarctic tourism are at an all-time high, with > 104 000 visitors to the region during the 2022–2023 season (IAATO 2023). Tourism-related cumulative environmental impacts have been little studied but may include wildlife disturbance, non-native species introduction, habitat destruction and pollution (Tejedo et al. Reference Tejedo, Benayas, Cajiao, Leung, De Filippo and Liggett2022). The industry has been largely managed by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), but the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties have been slow to agree on robust regulation, which is becoming increasingly necessary as visitor sites come under increasing pressure.

Ireland's foreign policy is based on the principle of global multilateral cooperation, demonstrated through its neutrality, a long-standing commitment to United Nations (UN) peacekeeping and the promotion of disarmament. Ireland served its fourth term on the UN Security Council in 2021–2022, where it demonstrated its ability to operate effectively at the highest levels internationally by showing its commitment to the rule of international law and advocacy for the protection of human rights and maintenance of international peace and security. Ireland has acted as an advocate for global environmental protection and biodiversity in international forums and has signed and ratified several multilateral agreements, including the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the UN Convention on International Trade and Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Bonn Convention and the Ramsar Convention. Ireland is also a member of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and a party to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC; National Parks and Wildlife Service 2024). However, none of these agreements have jurisdiction within the Antarctic Treaty area, and Ireland has not acceded to any of the international agreements that comprise the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). Ireland's existing track record of engagement in international conservation initiatives and agreements means it already has substantial expertise that could be beneficial in the multi-Party governance of the Antarctic continent and the Southern Ocean.

The Antarctic Treaty System

The primary instrument for Antarctic governance is the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed in 1959 and entered into force in 1961 (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Lowther, Gilbert, Waluda and Lee2023). The original signatories were the 12 countries whose scientists were active in the Antarctic region during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–1958. Among 67 nations, Ireland was an IGY participant, albeit its role in Antarctica was not substantial (Chapman Reference Chapman1959). The Treaty applies to the Antarctic Treaty area, which is the area south of latitude 60°S (Fig. 1). Provisions of the Treaty include that: Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only; freedom of scientific investigation in Antarctica shall continue; scientific observations and results from Antarctica shall be made freely available; military activity is prohibited, except in support of science; nuclear explosions and the disposal of nuclear waste in the Antarctic are prohibited; and territorial claims shall be put into abeyance (i.e. those of the claimant states: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK). At present, 57 countries have acceded to the Treaty, comprising the 12 original signatory nations plus 45 countries that have subsequently acceded. Participation in the governance of the Antarctic Treaty area is limited to the 29 Consultative Parties to the Treaty that comprise the 12 original signatory nations plus a further 17 nations that have attained consultative status by demonstrating ‘substantial scientific research activity’ in Antarctica, as set out in Article IX(2) of the Treaty. Consultative Parties contribute financially to the operation of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, based in Buenos Aires, and take it in turns to host the annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM; ATS 2023). The 28 nations that have acceded to the Treaty but have not attained consultative status (known as non-Consultative Parties) may not engage in governance decisions but are bound to carry out the provisions of the Treaty and decisions taken within its framework. However, it is not always clear whether or how these countries have enacted the Treaty in their domestic legislation, as without this accession could be seen as little more than a symbolic gesture. The Parties meet each year at the ATCM to discuss issues relevant to the governance of the Treaty area. Whilst not entitled to engage in decision-making, the non-Consultative Parties can submit Information Papers to the ATCM, and their opportunity to influence the Meeting should not be underestimated.

Figure 1. Map of Antarctica showing the research stations operated by European nations. CAMLR Convention = Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; EU = European Union.

The ATS is composed of three international agreements in addition to the Treaty. The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (also known as the Madrid Protocol or Environmental Protocol; signed 1991, entered into force 1998) designates Antarctica as a ‘natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’. All activities relating to Antarctic mineral resource prospecting and extraction are prohibited, except those undertaken for reasons of scientific research. The Protocol has six annexes, concerning environmental impact assessment, conservation of fauna and flora, waste disposal and management, prevention of marine pollution, area protection and management and liability arising from environmental emergencies (yet to enter into force). The Protocol established the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) as an expert advisory body to meet annually and provide advice and formulate recommendations to the ATCM in connection with the implementation of the Protocol (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Constable, Frenot, López-Martínez, McIvor and Njåstad2018). The Protocol has no end date, but under specific circumstances it does allow for renegotiation 50 years after it entered into force (i.e. 2048; Gilbert & Hemmings Reference Gilbert and Hemmings2015). Notably, a condition for attaining consultative status under the Treaty is the prior signature of the Protocol.

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS; signed 1972, entered into force 1978) was established to regulate the possible resumption of sealing activities in Antarctica; however, no sealing industry developed, and CCAS has now been largely superseded by the Protocol that, in effect, prohibits the commercial harvesting of seals (Convey & Hughes Reference Convey and Hughes2023).

The remaining major ATS legal instrument is the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention; signed 1980, entered into force 1982), which employs a whole-ecosystem management approach to ensure Southern Ocean fishing activities are not detrimental for Antarctic marine ecosystems, particularly for higher predators such as seabirds, seals, whales and fish that depend on krill for food (Constable Reference Constable2011). Unlike the Treaty or Protocol, where Contracting Parties are restricted to states, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) also accepts regional economic integration organizations that have committed to the CAMLR Convention through accession. Consequently, the European Union (EU) is one of the 37 Contracting Parties to the CAMLR Convention. Membership of the CCAMLR is open to any Contracting Party that is engaged in research or harvesting activities in relation to the marine living resources to which the CAMLR Convention applies. Acceding states (effectively Observers) are countries that do not wish or are unable to demonstrate research or harvesting activities in the CAMLR Convention area and do not take part in the decision-making process of the CCAMLR nor contribute to the budget.

The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (signed in 1946) predates the Antarctic Treaty and is not part of the ATS. However, it does have jurisdiction within the Antarctic Treaty area for the conservation of whales (IWC 2024). Ireland joined the International Whaling Commission in 1985.

In addition to compliance with and adoption of these legal instruments, prospective Consultative Parties need to demonstrate clear scientific ambitions, and therefore their engagement with the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR; see https://scar.org/) is almost essential for attainment of consultative status (SCAR 2023). SCAR initiates and coordinates high-quality international scientific research in the Antarctic region and provides objective and independent scientific advice to the ATCM and other organizations (including the UNFCCC and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) on issues of science and conservation affecting the management of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean and on the role of the Antarctic region in the Earth system (Walton Reference Walton and Berkman2011). SCAR Members include almost all of the Treaty Parties (as well as some non-Treaty Parties such as Iran, Luxemburg, Mexico and Thailand), as the organization is integral to international scientific collaboration across all natural and social science disciplines. Some non-Treaty Parties, such as Iran, may have joined SCAR as a first step towards initiating more formal engagement in Antarctic affairs (Madani & Hemmings Reference Madani and Hemmings2023).

Ireland, Antarctica and the European Union

Through its membership of the EU, Ireland sees itself as a constructive partner playing a central role in Europe. As a small country, Ireland is aware that an effective EU is essential for it to achieve its goals, both at home and on the international stage (Department of Foreign Affairs 2024). While the EU‘s overarching policy on the Antarctic has not been well articulated, many other environmental issues of interest to the EU and Ireland could be advanced through increased engagement in Antarctica - for example, in relation to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, more commonly known as the 30×30 initiative to protect 30% of the world's land, freshwater and oceans by 2030 (Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Schmidt-Traub, Mazzucato, Messner, Nakicenovic and Rockström2019, Gurney et al. Reference Gurney, Adams, Álvarez-Romero and Claudet2023, Convention on Biological Diversity 2024). Indeed, Ireland is taking major steps to increase the area of marine protected areas in its own waters and is in the process of developing the Marine Protected Areas Bill to support the delivery of its commitments (Enright Reference Enright2023). More generally, it has been suggested that the EU's Antarctic interests evolve around managing fisheries, saving the ocean and facilitating the scientific impact of its Member States (Dodds & Raspotnik Reference Dodds and Raspotnik2023).

Opportunities may exist for Ireland to gain access to the polar regions through its European engagement. The European Polar Board (EPB; https://www.europeanpolarboard.org/) focuses on major European strategic priorities in both the Arctic and the Antarctic regions (Colombo Reference Colombo2019). The EPB has a mission to improve European coordination of Arctic and Antarctic research by optimizing the use of European polar research infrastructures and the promotion of multilateral collaborations between its members. Current EPB membership includes research institutes, funding agencies, scientific academies and polar operators from across Europe. In the wider Antarctic region, 23 research facilities are operated by EU Member States, plus another seven being operated by Norway, Ukraine and the UK. Furthermore, 16 European research vessels operate regularly in the polar regions, and the German Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) and British Antarctic Survey (BAS) each operates an aircraft fleet in Antarctica. More broadly, the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP; see https://www.comnap.aq/) facilitates the exchange of information and opportunities for collaboration between national Antarctic programmes, with membership including all of the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties and several non-Consultative Parties that have active Antarctic science programmes. As observed by Dodds & Raspotnik (Reference Dodds and Raspotnik2023), ‘alongside China, Russia and the United States, the EU is a polar science superpower’.

Ireland's polar aspirations

Ireland is conspicuous as one of the very few European nations that is not a signatory to the Antarctic Treaty. This is surprising given the long history of engagement and achievement by the Irish in Antarctic exploration, which eclipses the early activities of many nations that have already acceded to the Treaty and participate in Antarctic governance. The relevance of Antarctica in today's world is demonstrated by countries continuing to accede to the Treaty, with Slovenia signing in 2019, Costa Rica in 2022, San Marino in 2023 and Saudi Arabia in May 2024. Other recent signatories include Malaysia, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Iceland (e.g. Tamm et al. Reference Tamm, Jabour and Johnstone2018); however, the connections of these countries with the exploration and history of Antarctica are negligible compared to that of Ireland.

Ireland has already demonstrated its interest in polar affairs through its application for Observer status to the Arctic Council (a region with which Ireland has a much closer proximity). During its application, the Irish government emphasized the country's 1) policy and scientific capacity, 2) experience as a proactive global actor and 3) proven capabilities in empowering vulnerable communities (Government of Ireland 2021). The application was unsuccessful, but most of these factors are equally relevant for engagement with the ATS, including Ireland's position of neutrality, belief in global cooperation, concerns regarding climate change, strengths in scientific and technological research and its maritime-influenced culture, heritage and identity (Middleton Reference Middleton2021).

Factors supporting a country's decision to engage with the ATS might include: historical activity within Antarctica; current activity by its nationals in the Treaty area, including scientists, adventurers and tourists; proximity of the country to the Antarctic; the existence of individuals or groups within the nation that champion accession to the Treaty; close ties with other nations active within the ATS; existing expertise in marine, polar or high-altitude logistics and research; and the capacity of the government to support engagement with the ATS. The aim of this paper is to 1) explore the level of engagement of Ireland and its citizens in Antarctica and Antarctic affairs, 2) report recent developments in Ireland's consideration of further engagement in the ATS and 3) consider how and to what extent that engagement might be manifested.

Methods

The Antarctic Treaty System and related organizations

Information on the Parties that are signatories and/or Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treaty and signatories to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty was obtained from the website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat (see https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Parties?lang=e). Country population data were obtained from the CIA World Factbook website pages on population (see https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/population/). Details on the countries that have acceded to the CAMLR Convention were obtained from the website of the CCAMLR Secretariat (see https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/membership). Information on countries' membership of SCAR (see https://scar.org/about-us/governance/members), COMNAP (see https://www.comnap.aq/our-members) and the EPB (see https://www.europeanpolarboard.org/about-us/membership/) was obtained from their respective websites.

Details concerning the attendance of non-Consultative Parties at the now annual ATCMs were obtained from the meeting Final Reports (available at https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings?lang=e). The number of papers submitted to the ATCM and CEP meeting by each non-Consultative Party was obtained from the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat Meeting Documents Archive (see https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e).

Irish Antarctic explorers

Information on the Irish nationals active in Antarctica during the ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration (c. 1897–1922) was obtained from the Dictionary of Irish Biography (see https://www.dib.ie) and Smith (Reference Smith2010). Details of Antarctic locations that have been named after Irish individuals were obtained from Headland (Reference Headland2021) and the SCAR Composite Gazetteer (see https://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/gaz/scar/).

Scientific outputs by Irish researchers

To identify total academic publication outputs by countries, bibliometric data were collected from the Web of Science using the search string below (taken from Gray & Hughes Reference Gray and Hughes2017; the term ‘candida’ was specifically excluded to eliminate false positives produced by the fungus Candida antarctica):

Topic Search (TS) = ((antarc* NOT (candida OR ‘except antarctica’ OR ‘except the antarctic’ OR ‘not antarctica’ OR ‘other than Antarctica’)) OR ‘transantarctic’ OR ‘ross sea’ OR ‘amundsen sea’ OR ‘weddell sea’ OR ‘southern ocean’)

The results were then filtered by type to include only articles and reviews published by authors affiliated with addresses located in Ireland.

Irish citizens' engaging in Antarctic tourism

Antarctic tourist visitation data for the 2022/2023 summer season were provided by IAATO.

Irish Parliamentary discussions on the Antarctic Treaty

Transcripts of debates within the houses of the Oireachtas Éireann (Irish Parliament) were accessed via the website https://www.oireachtas.ie/. A general internet search was undertaken to identify other examples of Irish engagement in Antarctica and details relevant to potential accession to the Treaty.

Results

The Antarctic Treaty System and related organizations

Ireland is the largest country by population within the EU not to have signed the Antarctic Treaty or any other agreements that constitute the ATS or joined any related organizations (see Fig. 2 & Table I). Only six other EU Member States have not signed the Treaty (i.e. Malta, Luxemburg, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia). Several other European countries with populations considerably lower than that of Ireland have signed Antarctic legal agreements and joined relevant international organizations. For example, both Slovenia (population: 2.1 million) and Estonia (population: 1.2 million) have signed the Treaty. Furthermore, Iceland (population: 360 000) and San Marino (population: 34 000) have signed the Treaty with populations of just 6.8% and 0.7% that of Ireland, respectively. Monaco, with a population of just 31 000, has signed the Treaty and the Protocol and is a member of SCAR. However, the benefit to Parties of Treaty accession, but without the attainment of consultative status and associated decision-making powers, is not always obvious, and, in some cases, accession may be largely symbolic. Fellow EU Members States Finland and Bulgaria have similar populations to that of Ireland and, as well as having signed the Protocol, they attained consultative status to the Treaty in 1989 and 1998, respectively, and thereby the opportunity to participate in Antarctic governance decision-making. They have also attained full membership of SCAR, COMNAP and the EPB and have acceded to the CAMLR Convention. Norway and New Zealand have similar populations to Ireland and, as original signatories to the Treaty, are Consultative Parties; however, with territorial claims on the continent, their engagement in Antarctic affairs may be a higher national priority. Uruguay is the Consultative Party with the smallest population (3.4 million), equivalent to 64% that of Ireland, yet it is also a Member of CCAMLR, SCAR and COMNAP.

Figure 2. Map showing nations' level of engagement with the Antarctic Treaty, including an inset showing in more detail the European nations.

Table I. European countries' engagement with international agreements and organizations relevant to Antarctica.

●: Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty; Signatory to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty; Member of CCAMLR; Full Member of SCAR; COMNAP Member.

○: Non-Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty; Acceding State to the CAMLR Convention; Associate Member of SCAR; Observer to COMNAP.

a The European Union is a Member of CCAMLR, alongside 26 other Member countries and 10 countries that have acceded to the CAMLR Convention.

b The Czech and Slovak Federal Republic signed the Protocol on 2 October 1992 and accepted the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the Arbitral Tribunal for the settlement of disputes in accordance with Article 19, paragraph 1 of the Protocol. On 31 December 1992, at midnight, the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic ceased to exist and was succeeded by two separate and independent states, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. 1 January 1993 is the effective date of succession by the Slovak Republic in respect of the signature of the Protocol by the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic.

c Estonia was an Associate Member of SCAR from 15 June 1992 to 22 August 2001.

Figure 3 shows the level of attendance at ATCMs by the non-Consultative Parties to the Treaty up until ATCM XLV (2023). There has been large variation in attendance across these Parties, but > 40% of Parties attended fewer than a quarter of eligible meetings. Table II shows the level of paper submissions to the ATCMs and CEP meetings during the period 2012–2023 (note that there was no ATCM or CEP meeting in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic; Hughes & Convey Reference Hughes and Convey2020). Two-thirds of non-Consultative Parties have submitted, in total, < 10 papers to these meetings, and one-third of Parties have not engaged in the production of any such papers whatsoever. In contrast, some Parties have shown considerable engagement, with the production of substantial numbers of papers either as sole authors or in collaboration with other Parties (e.g. Portugal and Türkiye). Often the more prolific Parties are those that have been active in Antarctic affairs for some time and may be seeking consultative status to the Treaty (e.g. Belarus and Venezuela).

Figure 3. Percentage attendance of non-Consultative Parties at Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs).

Table II. Non-Consultative Party engagement with the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting and Committee for Environmental Protection (as relevant).a

a Saudia Arabia acceded to the Treaty in May 2024 and is not included in this analysis.

b Parties having sought formally to attain consultative status to the Antarctic Treaty but without success.

Irish Antarctic explorers

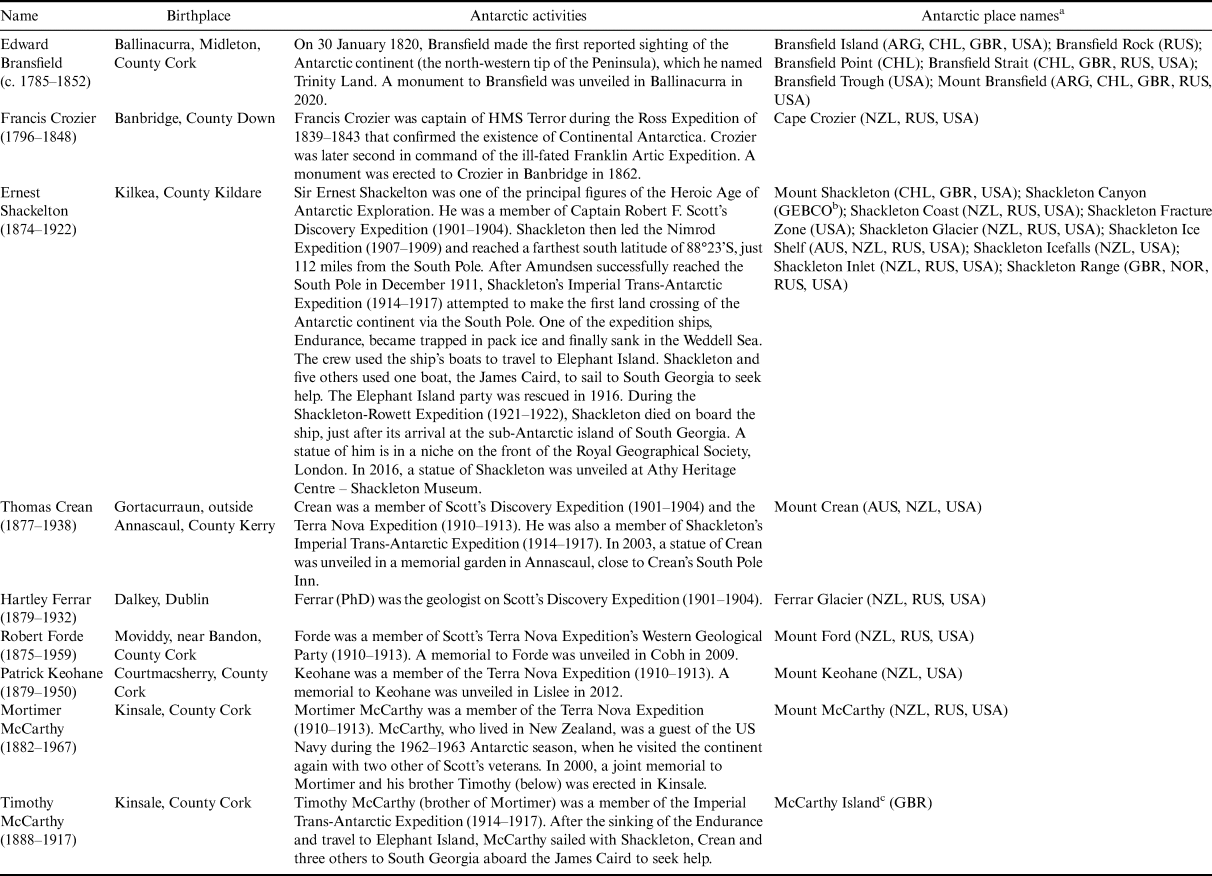

A list of some Irish individuals who participated in early Antarctic exploration is provided in Table III. This clearly demonstrates the substantial contribution of the Irish to the early exploration of the continent. Moreover, the awareness and celebration of Irish Antarctic accomplishments are often much higher than those of early explorers from other nations; for example, Ernest Shackleton and Tom Crean enjoy almost legendary status across the world.

Table III. Notable Irish individuals active in Antarctic exploration and associated place names in the Antarctic region.

a For each feature, the nations, including the name in their national Antarctic gazetteers, are noted.

b General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) Sub-Committee on Undersea Feature Names (SCUFN).

c McCarthy Island is located outside the Antarctic Treaty area on South Georgia.

Scientific outputs by Irish researchers

Ireland has a strong track record of producing academic work relating to Antarctica. Academic outputs have been produced by researchers from many of Ireland's centres of higher education and research institutes, including the University of Galway, Trinity College Dublin, Maynooth University, University College Cork and University College Dublin, on topics including geology, palaeontology, oceanography, glaciology, marine and terrestrial biology, geophysics and Earth system science (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Number of author affiliations for Irish centres of higher education and research institutes in papers published between January 2014 and February 2024 (148 author affiliations derived from 114 papers). ATU = Atlantic Technological University.

Table IV provides details of the production of academic papers concerning Antarctica between the years 2012 and 2021 by selected countries, including Ireland. Amongst the Consultative Parties, the USA, the UK and Australia produced the highest number of papers during the 10 year study period, at 10 177, 5729 and 4015 papers, respectively. However, when output is expressed as the number of papers per million of population, New Zealand has the highest number, with 337, followed by Norway, with 212. In contrast, Ukraine, Ecuador, China, Peru and India had three or fewer papers per million of population. For the non-Consultative Parties, the highest numbers of papers per million of population have been produced by countries with aspirations of attaining consultative status (e.g. Canada and Portugal). Ireland, with an output of 24 papers per million of population, has an academic output > 38% of the Consultative Parties and > 71% of the non-Consultative Parties. Nevertheless, Ireland's academic output is below that of Czechia (35 papers per million of population), which was the last Party to attain consultative status in 2014. When considering the paper output of the nine non-Treaty Parties that produced the highest number of Antarctic papers during the 10 year study period, Ireland was in the top three. Furthermore, of those nine non-Treaty Parties, Ireland had by far the highest number of papers per million of population (and considerably more than Mexico, Thailand and Iran, which are all members of SCAR; Table IV).

Table IV. Production of academic papers concerning Antarctica between the years 2012 and 2021 by Ireland compared with the Consultative, non-Consultative and other selected non-Treaty Parties.a

a Only the nine non-Treaty Parties that produced the highest number of papers during the period 2012–2021 are shown.

Irish citizens' engaging in Antarctic tourism

Table V provides information on tourist visitation to Antarctica by the citizens of selected countries, including Member States of the EU, other major non-EU European countries and nations with high levels of Antarctic visitors. The greatest numbers of visitors were from the USA, the UK and Australia, representing 52%, 7% and 7%, respectively, of the ~104 000 tourists that visited the Treaty area during the 2022/2023 summer season. In contrast, Irish citizens represented only 0.4% of Antarctic visitors; however, when considered in terms of visitors as a proportion of country population, Ireland had the fourth highest level of visitation within the countries of the EU and more visitors than Treaty signatory countries with similar levels of population, including Finland, Denmark and Slovakia. Both Norway and New Zealand are claimant states and Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treaty with populations similar to that of Ireland. Ireland had more visitors to Antarctica than Norway and around half of the visitors from New Zealand, in which is located the Antarctic gateway city of Christchurch.

Table V. Number of Antarctic tourist visitorsa from selected countries.

a The number of visitors travelling to the Antarctic Treaty area with tour companies that are members of the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO).

Irish Parliamentary discussions on the Antarctic Treaty

The two houses of the Oireachtas Éireann are the Dáil Éireann (the Lower House) and the Seanad Éireann (the Upper House), in which topics relevant to Antarctica (including the ozone hole, fishing, whale sanctuaries, climate change and arms limitations) have been discussed over several decades. Since the start of the millennium, questions and/or motions have been raised in both houses on over 30 occasions querying why Ireland has not acceded to the Treaty or asking for an update on its possible accession, which are described below. A member of the Seanad Éireann is known as a ‘Senator’, while a member of the Dáil Éireann is known as a ‘Teachta Dála’ (TD) or ‘Deputy’.

Early discussions

On 6 November 2003, Senator Shane Ross raised the question of Ireland's accession to the Treaty in the Seanad Éireann and cited Ireland's historical connection with the continent, the scientific opportunities, the shared ideals of nuclear disarmament and the protection of the environment for the benefit of all people as strong reasons for accession. In response, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dick Roche, said support for the Treaty was far from universal, with fewer than a quarter of the UN Member States being Parties to the Treaty. Rather, Ireland was sympathetic to the views of many UN states that 1) Antarctica should be seen as part of the common heritage of humankind and shared universally and 2) there should be a new UN agreement or treaty (as opposed to the Antarctic Treaty) as to the best means of ensuring full accountability for actions undertaken in and concerning Antarctica. Therefore, accession by Ireland to the Antarctic Treaty was not envisaged in the near future. A similar response was received on 3 May 2006 when a similar question was raised in the Dáil Éireann.

The Antarctic Treaty: the only show in town

On 27 September 2007, Senator Shane Ross again enquired about Ireland‘s accession to the Treaty and made the point in the Seanad Éireann that Ireland, unlike most other European countries, had still not acceded to the Antarctic Treaty, and he begged the then Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Deputy Trevor Sargent, ’to relieve us of this embarrassment‘. The Minister repeated the government’s earlier position. However, he added that the government was prepared to re-examine its relationship with the ATS, and the Minister for Foreign Affairs had asked officials in his Department to examine the issues involved in accession with a view to initiating a broader interdepartmental discussion on the question. Senator Ross expressed his frustration with the slow pace of progress and suggested that the initiation of an interdepartmental discussion is ‘a depressing prospect for anyone seeking progress on this issue’. The question of Ireland's accession to the Antarctic Treaty was raised again in the Dáil Éireann on 23 October and 27 November 2007 and received a similar response. However, at the latter meeting, the Minister stated that the Department was aware of the immense difficulties that would arise in seeking to negotiate a new UN treaty, and it had been decided to re-examine the question of accession to the Antarctic Treaty. Attempts were made in the Dáil Éireann to get updates on developments on the issue on 6 February and 11 March 2008, but little information was forthcoming.

An administrative burden, without benefit

Three years later, on 11 May 2011, Deputy Seán Ó Fearghaíl asked Eamon Gilmore (who was the Tánaiste (i.e. the Irish Deputy Prime Minister) and Minister for Foreign Affairs) for his views in relation to the Antarctic Treaty. Eamon Gilmore replied that a government decision of 9 June 2010 authorized work on this issue, including through a process of interdepartmental consultation. The question was repeated on 15 June 2011, with additional information limited to news of a seminar on the ATS hosted by the Department of Foreign Affairs, in cooperation with the Norwegian Embassy, in Dublin on 25 May 2011.

Updates were requested by various politicians on 20 September 2011 and 26 January 2012, but little further information was forthcoming. However, when Deputy Seán Ó Fearghaíl asked again on 9 February 2012, Tánaiste Eamon Gilmore replied that the associated legislative undertaking could be substantial in terms of preparing the necessary legislation and of the cost of maintaining any standing national structures, such as licensing systems, consequent on accession to the ATS. A similar question was asked by Deputy Seán Ó Fearghaíl on 15 March 2012 and again on 29 November 2012 and 22 January 2013. When Deputy Martin Heydon asked again on 17 October 2013, Eamon Gilmore replied that preparation for ratification by Ireland would impose substantial administrative burdens on several government departments that could not be supported at the present time. A similar response was given when the question was asked on 12 November 2013 and on 5 December 2013, when it was made clear that Ireland would not enjoy voting rights under the Treaty even if it signed and ratified it, and that it was unclear what useful purpose there would be in prioritizing it. However, the government would work with its partners in the EU and make their views known where appropriate.

Too costly, too busy

On 15 January 2014, Deputy Seán Ó Fearghaíl asked about plans to ratify the Antarctic Treaty. The response was that government departments had to concentrate their diminishing resources on their core business and areas of priority of national interest and concern and were not in a position to assume the administrative burden associated with the ATS ratification and ensuing Treaty obligations at the time. The question was repeated on 27 November 2014, 25 January 2017, 28 November 2019 and 23 July 2020, with a similar response being provided each time. However, when Deputy David Stanton asked about plans for Ireland to sign up to the ATS on 30 September 2021, the Minister, Simon Coveney, replied that the Department intended to undertake an assessment in the coming months to establish the nature and extent of these commitments, how they would align with government priorities, the potential for these commitments to develop over time and the legislative and other steps that would be required should a decision be taken to accede to the ATS.

Antarctic motion

On 8 December 2021, Senator Martin Vincent tabled a motion to the Seanad Éireann in which, amongst other things, he 1) noted that the Irish Government had recently applied for membership of the Arctic Council as an Observer, 2) highlighted the promises made over a decade earlier for the Department to make progress on the issue and 3) observed that the benefits of adherence to the Antarctic Treaty may be secured without incurring major expenditure. He requested an update from the Minister for Foreign Affairs on progress in the assessment of the commitments necessary for accession to the Antarctic Treaty. He also urged the government to promptly complete its assessment of necessary commitments for accession to the Antarctic Treaty and commit to taking all necessary steps to accede to the Treaty as soon as possible.

Nine senators from across the political spectrum spoke to the motion and all were supportive of Ireland's accession to the Treaty. The Minister for Foreign Affairs, Simon Coveney, noted that interest in a new UN treaty had waned and that the Antarctic Treaty was likely to remain the only practical framework for the regulation of human activity in Antarctica. Therefore, an assessment had been planned to establish the administrative and policy commitments necessary for accession to the Antarctic Treaty, including with other Departments, which was to achieve definite progress by the end of the first quarter of 2022. The Department had also commenced consultations with other countries of comparable size about their experience of accession to and membership of the ATS (including measures to implement the Treaty in domestic legislation).

Report by Professor Richard Collins

On 27 January 2022, Deputy David Stanton asked the Minister for Foreign Affairs whether his department had undertaken an assessment of Ireland‘s possible accession to the Antarctic Treaty. Simon Coveney replied that the Department had prepared detailed Terms of Reference for an analysis to be carried out on the range of legislative, policy and administrative measures required at a domestic level in order to accede to the instruments of the ATS. The report was produced by Professor Richard Collins (now of the School of Law, Queen’s University Belfast) and was submitted to the Department on 13 April 2022 (Collins Reference Collins2022). On 2 June 2022, Deputy Cathal Berry flagged that there had been a campaign for the last 20 years for Ireland to accede to the Antarctic Treaty, ‘but as yet there has been absolutely no delivery’. Deputy Eamon Ryan responded that the report produced by Professor Collins outlined the complex legislative requirements and that the Attorney General advised that what would seem a simple stroke of a pen has implications for the law that would apply to Irish citizens.

Ireland's place as a ‘developed northern European state’

In July 2022, the Department for Housing, Local Government and Heritage took over the policy lead role regarding Ireland's possible accession to the Antarctic Treaty. On 1 December 2022, Deputy David Stanton asked the Minister, Deputy Darragh O'Brien, whether his department had concluded consultations with other departments on Ireland's possible accession to the instruments of the ATS and whether he had formulated a recommendation for consideration by Government. The Minister reported his intention to form an interdepartmental group at the start of 2023 to determine what level of participation was appropriate for Ireland as a developed northern European state and to identify the structures and associated resource requirements for this participation. This group would look at how ATS engagement would tie in with Ireland's vision for a healthy and sustainably used global ocean. The group's report would form the basis of a submission to Government for consideration.

The issue of Ireland‘s accession to the Treaty was raised in the Seanad Éireann on 7 March 2023 and 23 March 2023, but with little further progress being made. On 17 January 2024, Deputy David Stanton asked the Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Deputy Malcolm Noonan, whether an interdepartmental group had been formed to evaluate Ireland’s possible participation in the ATS, as promised on 1 December 2022. The Minister replied: ‘The current priority in relation to the Marine Environment is to publish and seek the passage [of] the Marine Protected Areas Bill at the earliest opportunity. Once this legislation is sufficiently advanced we will be able to commence work on the Antarctic Treaty System.’

Discussion

Antarctica and the Irish

There can be little doubt that Antarctica holds a special place in Ireland‘s national consciousness. The dramatic exploits of Shackleton, Crean, Bransfield, Crozier and others are sources of national pride. The discovery of Shackleton’s ship Endurance in the Weddell Sea in 2022 and the imminent National Geographic film documentary on the search will promote Ireland‘s Antarctic credentials to a global audience (Amos Reference Amos2022, United Kingdom & South Africa 2022, Barrett Reference Barrett2023). With the world’s eyes on Ireland, perhaps this provides an opportunity to accede to the Antarctic Treaty and showcase Ireland‘s multilateralist values and its leadership in global affairs. Many of the early explorers have been commemorated by the erection of memorials in Ireland and beyond, with several having been unveiled since the turn of the millennium, indicating the ongoing significance of these individuals within Ireland’s cultural heritage. In 2022, the Irish government‘s new marine research vessel was named RV Tom Crean, following a suggestion by a Donegal schoolboy who was inspired by Crean’s Antarctic exploits (McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2022). As a further demonstration, An Post (the state-owned provider of postal services in Ireland) released a set of stamps, designed by David Rooney, commemorating the role of Irish Antarctic explorers (Murphy Reference Murphy2021; see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKAfIx8-25o). In 2008, the Central Bank of Ireland issued silver €5 and gold €100 coins featuring images of Shackleton and Crean to celebrate International Polar Year 2007/2008, in which Irish researchers participated (Krupnik et al. Reference Krupnik, Allison, Bell, Cutler, Hik and Lopez-Martinez2011). Aidan Dooley wrote and performed the award-winning one-man play Tom Crean - Antarctic Explorer. During the visit of President McAleese to New Zealand in 2007, Ireland expressed its interest in its role in Antarctic exploration through a donation (~€52 000) to the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust towards the conservation of historical huts on Ross Island, which were constructed during the ‘Heroic Age’ by Ernest Shackleton and others (Irish Times 2007).

Much has been done to raise the profile of Ireland‘s Antarctic heritage by the Shackleton Museum in Athy, County Kildare (https://shackletonmuseum.com/), which enjoys substantial local and regional political support. The Museum has a permanent exhibition devoted to Sir Ernest Shackleton and hosts the Shackleton Autumn School, which was established ’to commemorate the explorer in the county of his birth‘. The Autumn School provides a forum for the discussion of polar exploration and the presentation of artistic work relevant to Shackleton and polar exploration, and it has long held an interest in the further engagement of Ireland with the ATS. In 2020, the Autumn School hosted Senator of State Malcolm Noonan in a live discussion entitled ’Trick or Treaty: Ireland and the Antarctic Treaty, a discussion‘, at which the Senator noted Ireland’s strong link with Antarctica and expressed support for further consideration of Ireland‘s accession to the Treaty (available at https://www.facebook.com/athyheritage.centre/videos/trick-or-treaty-ireland-and-the-antarctic-treaty-a-discussion-minister-of-state-/2445559539071027/). Many of the individuals associated with the ’Heroic Age' of exploration have been commemorated through the naming of Antarctic locations by Antarctic Treaty Parties, including Argentina, Australia, Chile, New Zealand, Norway, the Russian Federation, the UK and the USA. At least 75 locations have been named after 45 Irish explorers, inventors and scientists (Headland Reference Headland2021).

Irish exploration and demonstrations of endurance have extended into the modern age. Several Irish mountaineers have summited Mount Vinson (Antarctica's highest peak, at 4892 m; Irish Seven Summits 2024). Mike Barry from Kerry was the first Irish citizen to walk to the South Pole; Clare O'Leary, from Bandon, County Cork, was the first Irishwoman to walk to the South Pole; and Mark Pollock overcame blindness to trek to the South Pole. During the 2019/2020 Antarctic summer season, Damian Foxall and marine biologists Lucy Hunt and Niall McAllister led a sailing expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula (Siggins Reference Siggins2019). It should be noted that Irish citizens, including researchers and operational support personnel, travel to Antarctica each year with the national Antarctic programmes of other countries. For example, Dr Susanna Gaynor travelled to Halley Bay, Antarctica, as the medical officer with the BAS in 2010 (RTE Radio 1 2022), and, more recently, Sadhbh Moore worked as a chef at Rothera Research Station, also with BAS (Frontier Reference Frontier2024).

Researchers located at centres across Ireland continue to make significant contributions to Antarctic knowledge with the production of more papers each year than most non-Consultative Parties and even some Consultative Parties. Gray & Hughes (Reference Gray and Hughes2017) reported the excellent quality of Irish Antarctic research as indicated by the high level of citations. In the 1980s, Irish Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Grace O'Sullivan was involved in the work of Greenpeace in Antarctica to highlight the need for greater environmental protection (https://www.graceosullivan.ie/; Clarke Reference Clark, Finger and Princen2013, Greenpeace 2024). Irish individuals continue to show leadership in the protection of the Antarctic environment, with Mike Walker holding the role of Europe and Strategy Coordinator for the non-governmental organization Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), and who previously contributed to the successful designation of the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area in 2016 (https://www.asoc.org/about/our-team/). Antarctic tourists from Ireland, while modest in number compared to some larger nations, represent a large proportion of the population relative to many other nations, indicating the ongoing interest of Irish citizens in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean.

Irish citizens have been proactive in expressing their desire for Ireland to accede to the Antarctic Treaty. A Facebook page has been established with 1900 followers entitled ‘Ireland should sign the Antarctic Treaty’ (https://www.facebook.com/IrelandShouldJoinTheAntarcticTreaty/), and petitions (e.g. No. P000022/16 and No. P00006/15) have been submitted to the Irish government calling for Ireland's accession to the Treaty.

Irish engagement with the Antarctic Treaty System: why now?

In the past two decades or more, the question of Ireland's accession to the Antarctic Treaty has been raised repeatedly in the houses of the Irish Parliament (on > 30 occasions). In the early 2000s, it was clear that the Government had a preference for engagement in Antarctic affairs in a more multilateral manner under the auspices of the UN. However, it became clear that negotiation of a new UN agreement on Antarctica was unlikely, and that the ATS was the only credible framework going forward. Analysis of parliamentary transcripts revealed several potential additional reasons for a lack of progress, including 1) the level of resources needed to investigate the issue, 2) the existing high departmental workloads and prioritization of other pressing issues and 3) the substantial level of complexity encountered when interacting across several governmental departments to progress the issue. A further possible reason for a lack of progress is that in the years since 2003, the individual in the role of Minister for Foreign Affairs has changed six times, which may have impacted upon the prioritization of the issue within the Department. However, with 1) the Irish economy in a good state compared to many other nations, 2) the important influences of the polar regions on the global climate and sea level becoming of increasing concern and 3) the potential to increase the protection of the marine environment in the seas around Antarctica, Ireland may now be in a position to consider afresh its future relationship with the ATS.

Promotion of a country‘s earlier Antarctic exploratory activities can be used to build a narrative supporting territorial claims and resource rights (Dodds & Collis Reference Dodds, Collis, Dodds, Hemmings and Roberts2017, Roura Reference Roura, Dodds, Hemmings and Roberts2017, Hingley Reference Hingley2022). Most, if not all, exploration of Antarctica by the Irish during the ’Heroic Age‘ was done under the flag of the UK (see Table III). As a result, Ireland’s early role in Antarctic exploration is inextricably connected with that of the UK. It is possible that part of Ireland‘s lack of engagement in Antarctic affairs, up to now, may have been due to a reluctance to be linked too closely with the UK’s polar activities and the promotion of its associated Antarctic sovereignty claims. However, it has been argued that there is an increasing post-colonial reimagining of Antarctica as a continent for peace and science undertaken by nations from across the globe, potentially making earlier imperial narratives less relevant today (Brazzelli Reference Brazzelli2014). In recent decades, the legal focus of the ATS has shifted away from the exploitation and use of Antarctica as a ‘global commons’ and more towards the conservation of the region for the ‘benefit of all mankind’ (Collins Reference Collins2022). Nevertheless, maintaining access to natural resources remains a focus for some Parties, which is in stark contrast to the more conservation-focused Parties. Given that conservation progress requires consensus within the Parties, these differing priorities have resulted in many international conservation efforts in the region being stifled, including ongoing efforts to designate a network of marine protected areas and agree specially protected species status for the emperor penguin (Jacquet et al. Reference Jacquet, Blood-Patterson, Brooks and Ainley2016, Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Ainley, Jacquet, Chown, Pertierra and Francis2022, Kubny Reference Kubny2022, Boulègue Reference Boulègue2023). It is against this backdrop that Ireland‘s multilateralism and conservation focus make it well placed to be a proactive advocate for effective conservation of the Antarctic continent, including by facilitating progress on multi-Party negotiations. Indeed, Ireland’s unique credentials for this role include its long and almost legendary association with the continent, coupled with its position as a staunchly neutral country that is free of any geopolitical ‘baggage’ associated with Antarctic territorial claims.

What could Ireland's engagement with the Antarctic Treaty System look like?

There are two main levels of engagement with the ATS. The lower level is to accede to the Treaty as a non-Consultative Party and/or become an Acceding State to the CAMLR Convention. Accession to these instruments entails no ongoing financial commitment to support the operation of the Treaty, the Protocol (as set out in ATCM Decision 1 (2003); https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/Measure/297) or CCAMLR. However, depending upon the approach taken, it may have several non-trivial requirements that may entail several years of governmental work to prepare the legislation and ensure its passage through the Irish Parliament (Barrett Reference Barrett, Footer, Schmidt, White and Davies-Bright2016, Tamm et al. Reference Tamm, Jabour and Johnstone2018). The major limitation to this approach is that it does not allow for participation in decision-making in either the ATCM or CCAMLR. Our analysis shows that many countries that have chosen to simply accede to the Treaty and/or CAMLR Convention may have done so for symbolic reasons, and, following accession, they have participated little in the ATS, with infrequent attendance of meetings and little or no submission of papers (e.g. only 12 out of 27 non-Consultative Parties attended ATCM XLV in Helsinki (2023); Fig. 3 & Table II). Furthermore, it is not known how many non-Consultative Parties have undertaken the associated legal and administrative work to make accession to the Treaty effective in their domestic legislation (Barrett Reference Barrett, Footer, Schmidt, White and Davies-Bright2016). The Irish Government showed that it was well aware of these limitations when Deputy Phil Hogan highlighted that signing the Treaty alone would not give Ireland voting rights at the ATCM and therefore was not a priority (International Agreements: Dáil Éireann debate, 5 December 2013).

The higher level of engagement with the ATS would entail acceding to the Treaty and the Protocol and then building a scientific research programme in Antarctica that would allow Ireland to demonstrate ‘substantial scientific research activity’, thereby facilitating its recognition as a Consultative Party and entitlement to partake in decision-making. Ireland could also become a full Member of CCAMLR through undertaking research and/or undertaking marine harvesting in the Southern Ocean, which would then entitle it to participate in decision-making within CCAMLR. However, the report prepared by Professor Richard Collins sets out, amongst other things, the need to draft new legislation to implement the core obligations associated with these instruments and the administrative burden associated with Ireland's full engagement with the ATS (Collins Reference Collins2022). Ireland would also need to identify and fund scientists to undertake relevant marine and terrestrial Antarctic research over the long term. Overall, the level of long-term commitment is far from trivial and would require input from multiple governmental departments, as well as the establishment of a governmental body to deal with ongoing tasks, including the scrutiny of environmental impact assessments undertaken for activities performed within the Treaty area, the allocation of necessary operational and environmental permits, the delivery of monitoring obligations and the production of annual reports to the ATCM on Irish activities in Antarctica.

Discussions in the Irish Parliament would appear to suggest that the Government has little interest in signing the Treaty or CAMLR Convention merely for symbolic reasons but sees a benefit to Ireland‘s strategic objectives only once consultative status has been attained and, potentially, full membership of CCAMLR. As the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Simon Coveney, said: ’There are serious commitments that we need to assess to ensure that we have the capacity to do this properly if we are going to do it‘ (Antarctic Treaty Motion: Seanad Éireann debate, 8 December 2021). This binary ’all-or-nothing‘ approach, while laudable, may limit Ireland’s opportunities to engage in polar fora and, at a minimum, influence ATS decision-making. Should Ireland take the step of Treaty accession, it would signify that Ireland was increasing its engagement in Antarctic affairs, in parallel with its quest for Observer status to the Arctic Council. Following Treaty accession, Ireland could participate in the annual ATCM and gain a fuller understanding of the complex challenges of Antarctic governance before taking the decision to work towards attainment of consultative status. Ireland‘s close working relations with other EU Member States may provide an opportunity for collaboration with Members with longer Antarctic experience, thereby enhancing Ireland’s understanding of the workings of the ATCM. Nevertheless, each country must weigh up the costs and benefits of accession to any international agreement or of a higher level of engagement, and its actions will be determined by the strategic directions it wishes to prioritize (e.g. see the cases of Türkiye (Karatekin et al. Reference Karatekin, Uzun, Ager, Convey and Hughes2023) and Portugal (Xavier et al. Reference Xavier, Gray and Hughes2018)).

CAMLR Convention

Ireland may have a wider range of options concerning interaction with CCAMLR. Ireland may 1) choose to engage further in CCAMLR initially as part of the EU delegation, 2) accede to the CAMLR Convention in its own right or 3) seek to attain full Membership of CCAMLR by engaging in fishery research and/or harvesting in the Southern Ocean. Ireland already has some prior experience of working with the EU at CCAMLR. On 30 June 2021, the Irish MEP Grace O'Sullivan, working with MEPs from other EU Member States, put forward a motion for an EU Resolution on the establishment of Antarctic marine protected areas and the conservation of Southern Ocean biodiversity. The Resolution was subsequently adopted by the European Parliament on 8 July 2021 (European Parliament reference: 2021/2757(RSP); see https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/ficheprocedure.do?lang=en&reference=2021/2757(RSP)). The Resolution was submitted as a statement from the EU and its Member States to the 40th meeting of CCAMLR (see CCAMLR-40 Final Report, para. 7.24, available at https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/e-cc-40-rep.pdf). Nevertheless, Ireland's accession to the CAMLR Convention, in its own right, would provide a clearer statement of its interest in the balance between harvesting and conservation in the Southern Ocean.

Building a case to become a Consultative Party in partnership with European Union Member States

Should Ireland accede to the Treaty and commence working towards the attainment of consultative status, active demonstration of scientific research activity in Antarctica could demand substantial resources depending upon the extent of engagement desired. While Ireland could develop its own logistics to facilitate Antarctic research - and may choose to do so, to some degree - it may prove more effective to collaborate with other Parties with existing infrastructure. Membership of the EPB and organizations such as EU-PolarNet (https://eu-polarnet.eu/) is likely to facilitate greater cooperation and collaboration with other European polar organizations. EU Member States operate 17 research stations within the Treaty area, and there may be opportunities for scientific collaboration and the use of spare capacity on these stations through the recently initiated EU project Polar Research Infrastructure Network (POLARIN; see https://www.awi.de/en/about-us/service/press/single-view/polarin-netzwerk-fuer-polare-forschungsinfrastrukturen.html; see also Fig. 1). The days of a prospective Consultative Party needing to construct a research station in Antarctica are over, and use of other Parties‘ facilities may save costs and reduce environmental impacts. For many years, the Netherlands has operated its Antarctic research programme using this logistical model, and it successfully attained consultative status in 1998. Similarly, Portugal has used spare capacity on the research stations of other Treaty Parties and seems likely to seek consultative status in the near future (Xavier et al. Reference Xavier, Gray and Hughes2018). There have been calls for the greater shared use of existing stations, and the EU, with 20 Member States that are signatories to the Treaty, may be well placed to coordinate such sharing of facilities and exchange of personnel, as is encouraged by the Treaty itself (Article III; Hemmings Reference Hemmings2011, Gray & Hughes Reference Gray and Hughes2017). Ireland could play a role in the ’Europeanization' of Antarctic research. It could also benefit from EU funding for its research activities in Antarctica.

Joining SCAR, and subsequent engagement and collaboration with this international body of Antarctic researchers, would be an almost essential step towards the demonstration of ‘substantial scientific research activity’ in Antarctica that is necessary for consultative status. The Marine Institute (the state agency responsible for marine research, technology development and innovation in Ireland), in collaboration with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, launched the Network of Arctic Researchers in Ireland (NARI) in 2020 (see https://www.nari.ie/). With natural and social scientists from across the island of Ireland, it may not be difficult to widen the scope of this organization to include researchers with interests in the Antarctic region. It would also be a reasonably simple step to establish a national committee of Antarctic Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS; see https://www.apecs.is/who-we-are/national-committees.html) that would foster early-career engagement by Irish researchers across both poles. Membership of Polar Educators International (PEI) could introduce Antarctica to younger generations across Ireland (see https://polareducator.org/about-pei/council-2022/; Roop et al. Reference Roop, Wesche, Azinhaga, Trummel and Xavier2019). These activities could also support Ireland's application for Observer status to the Arctic Council.

Conclusions and recommendations

Given Ireland's outstanding historical links to Antarctica, engagement with the ATS may seem like an obvious step to take. However, through a broader and more strategic lens, the benefits of its accession to the Treaty and CAMLR Convention may be less clear cut, as the legal, administrative and financial burdens would be non-trivial, particularly if attainment of consultative status - and associated participation in Antarctic governance decision-making - was the ultimate goal. Existing Consultative Parties of a similar or smaller size than Ireland include Bulgaria, New Zealand, Uruguay and the Arctic states Finland and Norway, but their strategic ambitions and priorities are likely to be different from those of Ireland. More generally, it may be reasonable to ask whether the ATS is fit for purpose when Ireland, as a small but economically rich nation, must think twice about accession to the various ATS legal instruments due to the anticipated extent of the associated legal, financial and administrative burdens (Haward & Jackson Reference Haward and Jackson2023, Roberts Reference Roberts2023). Furthermore, how many other less affluent nations may have already discounted or delayed engagement with the ATS due to these factors (Hemmings Reference Hemmings2022)?

The benefits of Ireland's accession to the legal instruments of the ATS may include 1) greater engagement in international research (including with EU partners), 2) an opportunity to engage in and promote environmental stewardship in the Antarctic and 3) the chance to provide leadership and promote multilateralism within a system that is encountering increasing geopolitical challenges. Should the Irish government decide it is appropriate to increase its engagement in the ATS, the following recommendations might be worthy of consideration:

• Accede to the Antarctic Treaty, which would signal Ireland's interest and engagement in Antarctic affairs and act as a foundation upon which further engagement might be built.

• Understand that attaining the right to engage in Antarctic decision-making takes time, with the average interval between accession to the Treaty and attainment of consultative status being 11.5 years for a European state. Scientific, legislative and administrative planning should be on this timescale.

• Promote domestically and internationally Ireland's unique Antarctic history and its core foreign policy principles of neutrality, multilateralism, peace and environmental conservation.

• Encourage the EU to develop an Antarctic policy framework, which might harmonize with Ireland's own strategic policy for the region.

• Increase Irish polar research expertise by strengthening existing partnerships and developing new collaborations with EU Member States active in Antarctica as well as Antarctic Treaty Parties from other areas of the world. Allocate long-term funding to support this research.

• Become a member of the EPB and/or join POLARIN as routes for increasing scientific collaboration and possibly gaining access to polar research facilities. EPB membership would have the additional benefit of strengthening Ireland's application for Observer status to the Arctic Council.

• Join SCAR, with Irish representation possibly delivered by an expansion of the remit of NARI to include Antarctica.

• Initiate or increase Irish policymaker presence at the annual CCAMLR Meeting as part of the EU delegation in order to gain experience of operating within the ATS.

• Consider the potential benefits of signing the CAMLR Convention and/or the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty.

• When investigating options for gaining access to Antarctic sites for research activities, consider carefully the financial and environmental benefits of partnering with countries with existing Antarctic stations rather than the construction of a new Irish research station.

Acknowledgements

KAH is supported by NERC core funding to the BAS Environment Office. We acknowledge and thank Amanda Lynnes (Director of Environment & Science Coordination, IAATO) for the provision of tourism data, Louise Ireland (BAS Mapping and Geographic Information Centre (MAGIC)) for the preparation of Figs 1 & 2 and Beverley Ager (BAS Library) and Andrew Gray (University College London) for the provision of bibliometric data. Claire Boyle is acknowledged for the provision of comments on a late draft of the manuscript. The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This paper is a contribution to the ‘Human Impacts and Sustainability’ research theme of the SCAR Scientific Research Programme ‘Integrated Science to Inform Antarctic and Southern Ocean Conservation’ (Ant-ICON).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Author contributions

KAH conceived of the study, and both authors participated in data collection, writing and editing of the manuscript.