INTRODUCTION

The Early Bronze Age mortuary traditions in the Aegean and Anatolia consisted mainly of extramural burials for adults (Stech-Wheeler Reference Stech-Wheeler1974; Massa and Şahoğlu Reference Massa, Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011). Our knowledge of burial habits in central Anatolia is quite limited and is mostly based on small-scale excavations in extramural cemeteries mainly dating to the second half of the third millennium BC (Fig. 1). Pithos, stone cist and simple pit burials constitute the main burial types in Central Anatolia (Özgüç Reference Özgüç1948). Rich graves uncovered at sites like Alacahöyük (Koşay Reference Koşay1951), Horoztepe (Özgüç and Akok Reference Özgüç and Akok1958), Resuloğlu (Yıldırım Reference Yıldırım2006; Yıldırım and Ediz Reference Yıldırım and Ediz2005; Reference Yıldırım and Ediz2006; Reference Yıldırım and Ediz2007; Reference Yıldırım and Ediz2008; Yıldırım and Zimmermann Reference Yıldırım and Zimmermann2006), Kalınkaya (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2006; Reference Zimmermann2007), Merzifon–Oymaağaç (Özgüç Reference Özgüç1978), and Kültepe–İnler Dağı (Öztürk and Kulakoğlu Reference Öztürk and Kulakoğlu2019), as well as the ‘treasures’ from Mahmatlar (Koşay and Akok Reference Koşay and Akok1950) and Eskiyapar (Özgüç and Temizer Reference Özgüç, Temizer, Mellink, Porada and Özgüç1993) clearly demonstrate the high level of wealth achieved, which was also displayed and consumed through burial practices by the cultures of this region during the Early Bronze Age. These rich cemeteries in central Anatolia provide important information on both the burial habits in the region as well as the development of metallurgy. Finds from central Anatolian cemeteries form the basis of our increasing knowledge of the development and spread of tin-bronze in Anatolia and beyond.

Fig. 1. Map of sites mentioned in the text. Map: Ümit Gündoğan and Vasıf Şahoğlu.

Western Anatolia is an important region in understanding the interregional dynamics and connections within a wide geographical region extending from the central Anatolian plateau to the Aegean Sea. As a result of excavations carried out at sites like Troia (Korfmann Reference Korfmann2001), Küllüoba (Efe Reference Efe and Belli2000; Efe and Ay-Efe Reference Efe and Ay-Efe2001), Beycesultan (Lloyd and Mellaart Reference Lloyd and Mellaart1962), Aphrodisias (Joukowsky Reference Joukowsky1986), Karataş-Semayük (Mellink Reference Mellink1970a; Reference Mellink1970b; Reference Mellink1994), Liman Tepe (Erkanal Reference Erkanal and Sey1996; Reference Erkanal, Betancourt, Karageorgis, Laffineur and Niemeier1999; Reference Erkanal2001; Reference Erkanal, Erkanal, Hauptmann, Şahoğlu and Tuncel2008a; Erkanal and Erkanal Reference Erkanal, Erkanal, Yalçın and Bienert2015; Erkanal and Şahoğlu Reference Erkanal, Şahoğlu, Bingöl, Öztan and Taşkıran2012a; Reference Erkanal, Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016), Bakla Tepe (Erkanal Reference Erkanal, Erkanal, Hauptmann, Şahoğlu and Tuncel2008b; Erkanal and Erkanal Reference Erkanal, Erkanal, Yalçın and Bienert2015; Erkanal and Özkan Reference Erkanal, Özkan, Özkan and Erkanal1999; Reference Erkanal and Özkan2000; Erkanal and Şahoğlu Reference Erkanal, Şahoğlu, Bingöl, Öztan and Taşkıran2012b; Gündoğan, Şahoğlu and Erkanal Reference Gündoğan, Şahoğlu and Erkanal2019; Gündoğan Reference Gündoğan2020; Keskin Reference Keskin, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008; Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Gillis and Sjöberg2008; Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016), Yenibademli Höyük (Hüryılmaz Reference Hüryılmaz2006a; Reference Hüryılmaz2006b) Ulucak (Çilingiroğlu et al. Reference Çilingiroğlu, Derin, Abay, Sağlamtimur and Kayan2004), Çeşme-Bağlararası (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Felten, Gauss and Smetana2007; Reference Şahoğlu, Bingöl, Öztan and Taşkıran2012; Şahoğlu et al. Reference Şahoğlu, Çayır, Gündoğan and Tuğcu2018), Yassı Tepe (Derin Reference Derin, Göncü, Ersoy and Akar Tanrıver2019), Çukuriçi Höyük (Horejs and Mehofer Reference Horejs, Mehofer, Hauptmann and Modarressi-Tehrani2015; Horejs and Schwall Reference Horejs, Schwall, Dietz, Mavridis, Tankosic and Takaoğlu2018) and Çine-Tepecik (Günel Reference Günel and Horejs2014; Reference Günel, Şahoğlu, Tuğcu, Kouka, Gündoğan, Çayır, Tuncel and Erkanal-Öktü2023), our knowledge of Early Bronze Age settlement organisation and the socio-economic and political structure of the region has been much improved (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu, Şevketoğlu and Erbil2019) (Fig. 1).

While settlement excavations have furnished data on chronology, settlement structures and production activities, various cemeteries have provided information on socio-economic organisation and burial practices. Numerous cemeteries or individual graves have been excavated in western Anatolia, while many more have been found already destroyed through illicit digs. Although finds from such illegal activities have sometimes found their way to museums and do provide some information on burial habits, such data is in no way comparable to those obtained through well documented systematic excavations (Stech-Wheeler Reference Stech-Wheeler1974; Massa and Şahoğlu Reference Massa, Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011).

Our knowledge of burial practices in Early Bronze Age western Anatolia has increased through such systematically excavated and published cemeteries (Fig. 1). Among these, Iasos cemetery with its stone cist graves (Pacorella Reference Pacorella1984) and Bakla Tepe cemetery with its pithos, stone cist and pit burials (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016) demonstrate heterogeneity in grave types in coastal western Anatolia during this period (Massa and Şahoğlu Reference Massa, Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011). The recently excavated Çapalıbağ cemetery in Caria region (Oğuzhanoğlu and Pazarcı Reference Oğuzhanoğlu and Pazarcı2020)Footnote 1 and Kesikservi cemetery in Bodrum (Aykurt et al. Reference Aykurt, Böyükulusoy, Benli-Bağcı and Deniz2023) date to the first half of the third millennium BC. Nevertheless, our knowledge of the burial practices of prehistoric Anatolia is largely based on research carried out on cemeteries dating to the late Early Bronze (EB) II / early EB III period. In this respect, the cemeteries of Demircihöyük-Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000; Massa Reference Massa2014), Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991) and Kaklık Mevkii (Topbaş, Efe and İlyaslı Reference Topbaş, Efe and İlyaslı1998), located in inland north-west Anatolia, enable comparisons between western and central Anatolia. Harmanören-Gündürle (Özsait Reference Özsait2000) and Elmalı-Karataş cemeteries further south in inland south-western Anatolia (Mellink Reference Mellink1970a; Reference Mellink1970b; Reference Mellink1994) and the recently excavated Kumyer cemetery in coastal south-western Anatolia (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013) are some of the other systematically excavated pithos cemeteries dating to the third quarter of the third millennium BC. Bakla Tepe (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016) and Ulucak (Çilingiroğlu et al. Reference Çilingiroğlu, Derin, Abay, Sağlamtimur and Kayan2004) in the Izmir region also have pithos burial cemeteries dating to the late EB II and EB III periods.

Within this context, the extramural cemetery at Çeşme–Boyalık presents a new burial tradition for western Anatolia, previously completely unknown, with important implications for understanding the region's wider socio-cultural connections.

ÇEŞME–BOYALIK CEMETERY

Excavations at Boyalık were carried out by the Çeşme Archaeological Museum in 2000 at Izmir Province, Çeşme District, Sakarya Quarter, Map 24J-11, Block 5614, Parcel I and in 2005 in the adjoining Sakarya Quarter, Map 24J-11, Block 5614, Parcel 8. The excavations were undertaken as rescue work in an area which was listed as a third degree archaeological site. Four graves (Graves 1–4) were uncovered in 2000 and a further two (Graves 5–6) in 2005 (Şahoğlu, Vural and Karaturgut Reference Şahoğlu, Vural and Karaturgut2009).

A total of 15 test trenches varying in shape and size (Fig. 2) were opened across the investigated area in 2000 and 2005. The trenches were usually T-shaped with a size of 7 × 7 × 1 m but some of them were later extended depending on the finds unearthed at these spots. The depth of the trenches varied between 0.65 m and 1.80 m, again depending on the nature of the volcanic porous bedrock and the presence or absence of archaeological features. Very few of the trenches yielded visible archaeological deposits and, when necessary, test trenches were extended into larger excavation areas (Fig. 2b). Excavations at Boyalık cemetery revealed a total of six graves that seem to be concentrated mainly in the eastern part of the excavation area (Fig. 2a). The excavated trenches and the plots these trenches belonged to have since been built upon and are now under modern buildings. Thus, further archaeological investigation of this cemetery is impossible.

Fig. 2. Plan of Çeşme–Boyalık cemetery showing the excavated test trenches, found graves and other features.

The graves excavated at this cemetery are in many ways unique for western Anatolia, although similar grave types are known from elsewhere in the Aegean. Five of the six excavated graves can be classified as rock-cut chamber tombs, whereas a pithos burial has also been unearthed in close association with one of them. Some of the graves have been recorded as ‘pit graves’ by the excavators, but it is most likely that these graves also represent rock-cut chamber tombs whose roofs have collapsed. The function of three other pits dug into bedrock can also be questioned according to their contents. A ‘channel’-like feature cut into the bedrock across the excavated area constitutes another interesting element at Çeşme–Boyalık cemetery (Fig. 2).

The graves usually contained multiple burials, and it seems that older interments were pushed to the sides of the grave when a new body was going to be interred. Unfortunately, the skeletal remains are described as being in very bad state of preservation due to the characteristics of the soil matrix, which did not allow a proper study at the time of excavation.Footnote 2 Besides pottery, metal finds, obsidian and spindle whorls were also found as grave goods in the graves.

Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 1

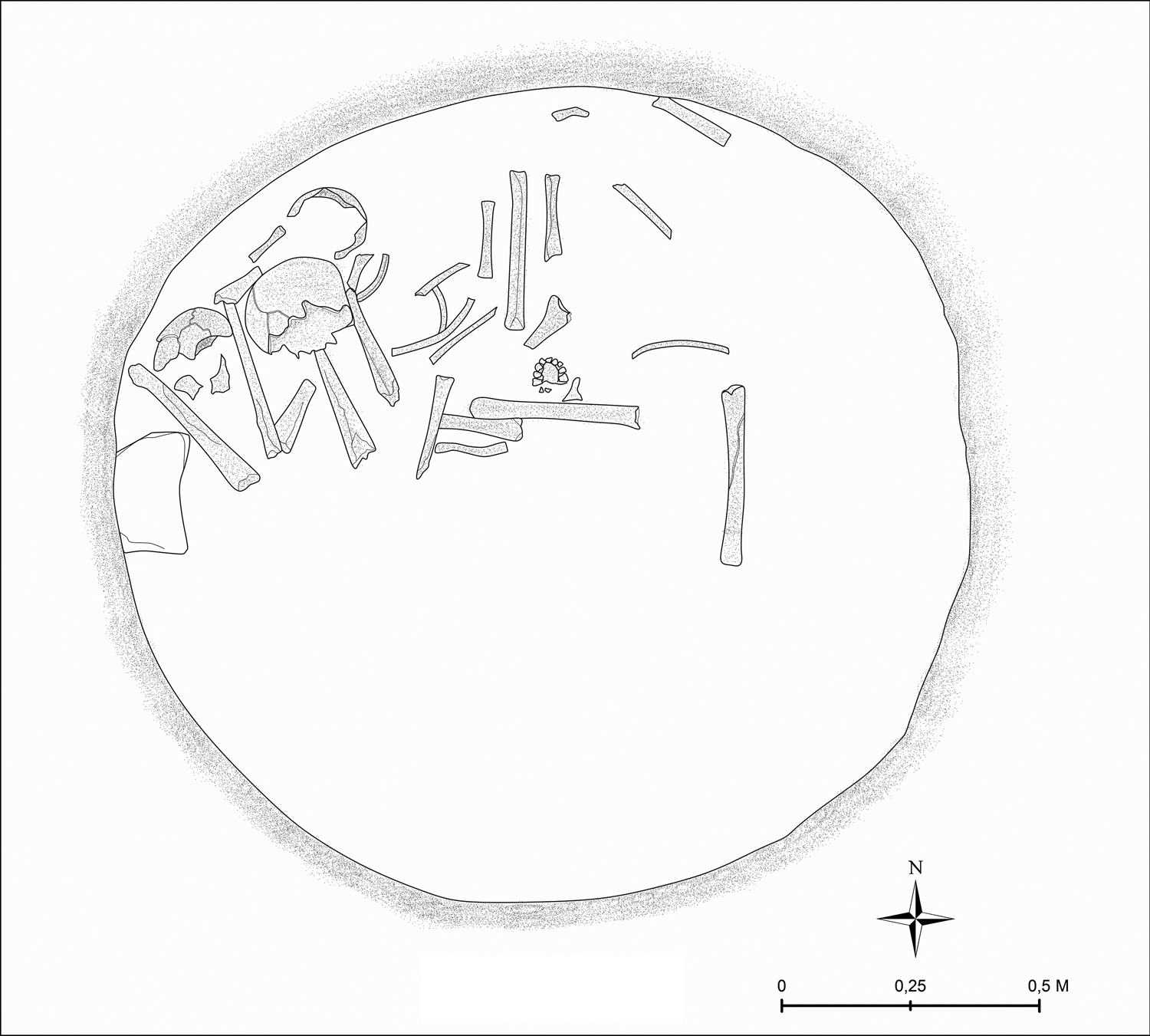

Grave 1 was identified in the eastern part of test trench 2 (Fig. 2). This is a circular pit grave cut into the volcanic porous bedrock and has a diameter of c. 1.60 m (Figs 3–4). The grave contained remains of at least three individuals based on their skulls, but there might be more. The skeletal remains were disarticulated and located in the north-western side of the grave (Figs 3–4). The deposition of the skeletal remains indicates multiple use of the grave at different times. There is a ‘pillow slab’ next to one of the skulls – a characteristic attested in almost every grave at the cemetery. The upper layers of the grave pit included some fragments of pithoi and some ceramic sherds. The grave was excavated with the assumption that it was a pit grave during the excavations, but it is most probably a rock-cut chamber tomb with a collapsed roof based on the evidence we see in Grave 2 within this cemetery.

Fig. 3. Plan of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 1. Drawing: Ramazan Güler.

Fig. 4. Photo of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 1 showing the grave chamber and the burials inside. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

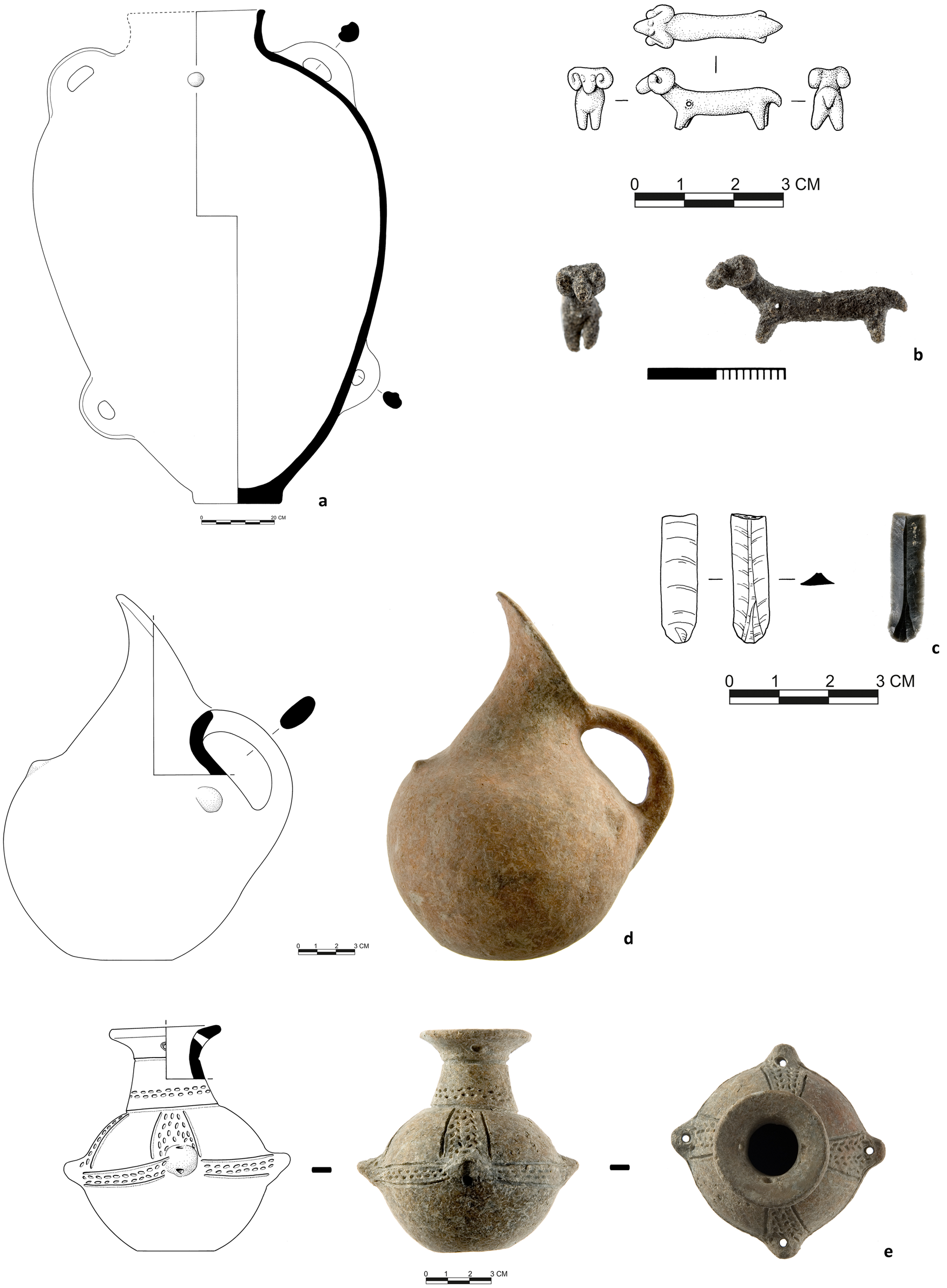

The inventory of grave finds included a fragmentary pithos (preserved dimensions 0.50 × 0.40 m) and some other sherds found just underneath the surface soil. A beak-spouted jug (Fig. 5b) and an incised spindle whorl (Fig. 5c) were found in the central part of the grave at a higher elevation overlying a badly preserved horizontal handled bowl (Fig. 5a) which was found c. 0.75 cm to the east of these finds. A small spiral shaped copper-based ring (Fig. 5d) was also found during the dry sieving of the soil of the grave.

Fig. 5. Cat. nos (a) BOY 00/01; (b) BOY 00/02; (c) BOY 00/03; and (d) BOY 00/04. Finds from Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 1. Drawings: Douglas Faulmann, Photos: Chronis Papanikolopoulos.

Inventory of finds from Grave 1

-

BOY 00/01 (horizontal handled bowl). The badly preserved bowl has an asymmetrical rim and must have had three rounded, triangular projections on the plain rim (one missing) (Fig. 5a). The body is slightly rounded. The base is flat and the bowl has a single horizontal handle, which is oval in section, attached just below the rim. The bowl is low fired and is relatively light in weight. The fabric is quite porous due to burnt organic inclusions. It also contains mineral inclusions like semi-transparent crystalline grains and white particles with sharp edges. The vessel surface is reddish-brown slipped (2.5 YR 5/6) both inside and outside, which is mostly worn. The bowl has been restored and about one third of it is missing.

-

BOY 00/02 (beak-spouted jug). The beak-spouted jug has a short and relatively wide neck and an almost pear-shaped body with a flat base (Fig. 5b). The D-section vertical strap handle is attached to the rim at the lower end of the spout and the shoulder. There are three circular knobs on the shoulder of the vessel, set at an equal distance from each other. The vessel is crudely shaped and not quite symmetrical. The vessel cannot stand on its base when empty. The shape of the vessel, the sharp edges on the handle and the presence of the knobs are all considered as evidence of skeuomorphism (i.e. imitation of metal prototypes). The fabric is relatively coarse with semi-transparent crystalline grains and white particles with sharp edges as well as organic temper. The biscuit has a thick black core. The jug has a burnished reddish-brown slip (2.5 YR 4/3; 7.5 YR 5/6) on the outside and on the inner part of the neck. The slip is worn in the front and lower part of the vessel. The vessel has been restored.

-

BOY 00/03 (spindle whorl). The biconical spindle whorl has a perforation along its long axis measuring 0.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 5c). It has two incised zigzag lines encircling it at its widest part. Another incised line encircles the perforation on the upper part. Four alternate vertical incised lines are drawn from this circle, each ending with a small, incised circle 0.5 cm in diameter, dividing the spindle whorl's upper half into four. The spindle whorl is brown slipped and burnished and is a characteristic form for this period.

-

BOY 00/04 (spiral ring). The copper based spiral ring has a diameter of c. 1.6 cm and a thickness of c. 0.2 cm (Fig. 5d). The two ends of the spiral were flattened, each resembling a ‘snake head’. The metal is highly corroded. It might have been used as a ring or more probably as an earring.

The fill of the grave also included the lower half of a big jar / pithos along with various pithos fragments (Fig. 6c) with plastic rope decoration (Fig. 6b) and large knobs (Fig. 6d). Other pottery sherds include the foot of a tripod vessel (Fig. 6e) and rim fragments of a wide mouthed jar (Fig. 6a). The fabrics of these vessels are in accordance with the local fabrics of Boyalık. They are porous due to organic inclusions along with semi-transparent crystalline grains and white grains with sharp edges. All the sherds also show a typical grey core in their biscuit. The leg and the pithos fragments are characterized by the presence of a heavily worn red slip (2.5 YR 4/6) and appear (at least macroscopically) identical to the typical Boyalık fabric, which may be an indication that the pithos fragments belong to the same vessel – a possible pithos burial which is related to Grave 1.

Fig. 6. Pottery fragments from the fill of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 1. Drawings: Douglas Faulmann.

Çeşme–Boyalık Graves 2 and 3

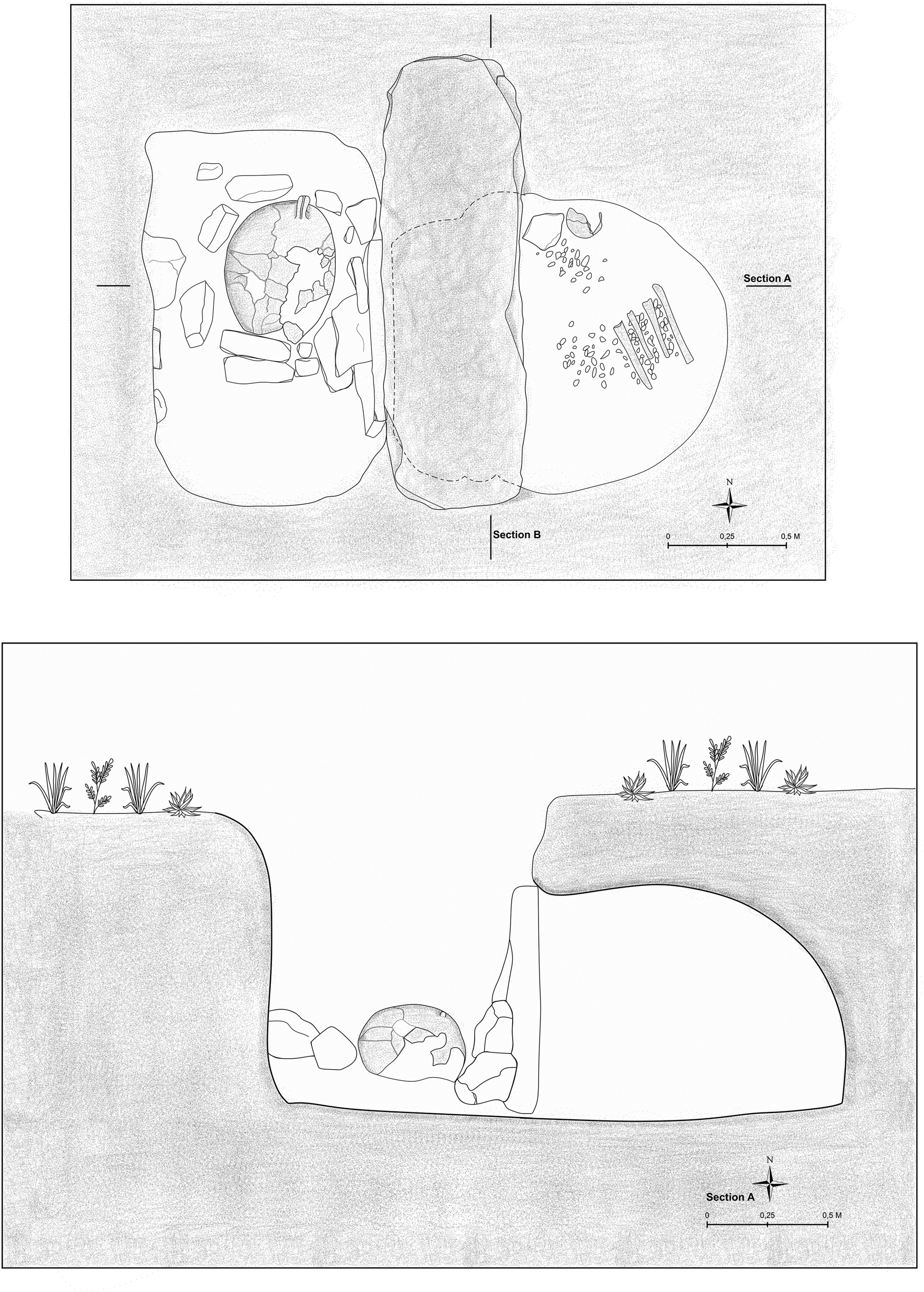

Grave 2 was identified in the western part of test trench 2 (Fig. 2). It is the best-preserved example reflecting the general character of the graves at Boyalık cemetery. This grave was cut into the volcanic porous bedrock and has a domed roof (Figs 7, 8 and 9). Only part of the roof was preserved on top of the stomion, located in the front (western) part of the grave. It clearly demonstrates the original shape of these rock-cut chamber tombs at Boyalık cemetery. The grave chamber has a roughly oval shape measuring c. 1.45 m at its widest part and a preserved height of at least 0.80 m. The chamber itself opens to a dromos shaft, which measures c. 1.51 × 0.90 m, through a stomion which was covered on the dromos side by a vertically placed large stone slab measuring 0.85 × 0.65 m. The skull was located in the northern part of the chamber and was found adjacent to a ‘pillow slab’ (Figs 8–9). The skeletal remains in the grave were piled up in the eastern part of the chamber and were overlain by the grave goods. The fact that the grave chamber can be accessed through the dromos shaft and the stomion at any time, and the multiple burials attested at other similar grave chambers within the cemetery, strongly support the possibility of this grave being used for multiple burials.

Fig. 7. Photo of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 2 showing the domed ceiling of the grave chamber carved into the bedrock. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

Fig. 8. Photo of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 2 showing the grave chamber. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

Fig. 9. Plan and section drawing of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 2. Drawing: Ramazan Güler.

Immediately outside the stone slab covering the stomion of the chamber tomb (Grave 2) and inside the dromos shaft was a small pithos grave (Grave 3) (Fig. 10). The pithos (BOY 00/05) was lying in a north–south orientation with its mouth facing south. The sides of the horizontally placed pithos were tightly supported by irregular stones. A few rows of stones were placed around the mouth of the pithos to seal its opening, and they encircle the pithos in a roughly rectangular form. The pithos has a short, almost cylindrical neck and a long oval body narrowing towards the flat base (Fig. 11a). It has four vertical handles, two on the shoulder and two on the lower part of the body, on opposite sides. The handles are oval in section, but on the outer faces, two grooves were carved close to the sides, raising the central part of the handle like a ridge. The pithos fabric is reddish brown (5 YR 4/4) and has a thin dark grey core in its biscuit. It is hand made, and is plainly smoothed except for the neck, which is red slipped (10 R 5/8).

Fig. 10. Photo of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 3. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

Fig. 11. Cat. nos (a) BOY 00/05; (b) BOY 00/09; (c) BOY 00/08; (d) BOY 00/06; and (e) BOY 00/07. Pithos of Grave 3 and the finds from Grave 2. Drawings: Douglas Faulmann. Photos: Chronis Papanikolopoulos.

Some skeletal remains were discovered inside the pithos, which was devoid of any burial goods. The human bones display evidence of burning, which may indicate a partly cremated body. It is highly likely that the association of this pithos burial with the rock-cut chamber tomb is significant. Any attempt to lift the covering slab of the stomion to gain access to the chamber tomb would have damaged the pithos. The pithos was intact, demonstrating that no further burials were interred in the chamber tomb after the pithos was inserted into the dromos.

The inventory of grave finds included a small beak-spouted jug (Fig. 11d) which was located at a higher level than all the other finds in the grave, a pyxis with string-hole lugs and incised decoration (Fig. 11e), an obsidian blade (Fig. 11c) and a small silver figurine depicting a ram (Fig. 11b).

Inventory of finds from Grave 2

-

BOY 00/06 (beak-spouted jug). The beak-spouted jug has a short and wide neck narrowing towards the beak (Fig. 11d) which sharply flares, a detail which makes it different from BOY 00/01. The neck is inclined towards the back. The body is globular with a flat base. The vertical strap handle, with an oval section, joins the rim at the lower part of the beak-spout to the widest part of the body. Of the three knobs on the vessel, one is located below the front of the spout and the others on either side of the handle, thus slightly differing from the example from Grave 1, which is also larger than this particular example. The vessel is intact, and the fabric seems quite similar to that of the rest of the pottery from the cemetery. The jug is reddish-brown slipped (2.5 YR 4/3) and burnished.

-

BOY 00/07 (incised pyxis). The pyxis has an everted flaring rim with a collared neck, globular body and a flat base (Fig. 11e). The rim has four pierced string holes more or less equidistant from each other mid-way between the rim and the neck, aligned with the four vertically pierced knob lugs on the widest part of the body. The pyxis clearly had a small lid, which is missing. The vessel is intact but the visible inclusions suggest a similar fabric to that evidenced from the rest of the Boyalık material. It has a reddish-brown slip and is finely burnished. The individual parts of the vessel are emphasised through incised and impressed decoration. Where the mouth of the vessel meets the neck, there is a horizontal incised line encircling the upper part of the neck; another incised line running around the neck's full circumference delineates the neck from the body. In between these two horizontal lines are two rows of impressed dots encircling the lower part of the neck. On the shoulder of the vessel, four panels, each wider at the base and slightly narrowing towards the neck, are placed between the string-hole knob lugs and the holes placed below the rim at the mouth of the vessel. These panels are also filled with impressed dots, sometimes resembling a herringbone pattern. There is evidence that incisions were once filled with a white infill in order to highlight the decoration on the vessel's surface.

-

BOY 00/08 (obsidian blade). One obsidian blade with a triangular section (2.6 × 0.7 × 0.25 cm) was found in this grave (Fig. 11c). The grey veins on the obsidian which are visible in macroscopic analysis more probably indicate a Melian source.

-

BOY 00/09 (ram pendant). A small silver pendant in the form of a ram, which measures 3 cm in length, 1.3 cm in height and 0.6 cm in width, was also found in Grave 2 (Fig. 11b). It has a long horizontal body and a relatively long neck. The legs of the ram were formed as small triangular projections c. 0.4 cm in height. Its tail is also represented with a triangular projection, which points downwards. Although its body reflects a somewhat more stylised form, the horns of the figurine, above a triangular projection representing the head, are exceptionally naturalistic. A string-hole immediately beneath the neck and above the front legs suggests that this must have been used as a pendant.

Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 4 (?)

Grave 4 (?) was discovered outside test trench 2, a few metres north of Grave 1 (Fig. 2). The ‘grave’ comprises a round pit cut into volcanic porous bedrock measuring c. 0.75 m in diameter (Fig. 12). A roof associated with this feature could not be identified during excavation. Nevertheless, a layer of rocky stones was encountered at the uppermost levels, which also included coarse pottery sherds scattered among them. A ‘tripod jar with a spout’ was found below the layer of volcanic porous rubble, c. 1 m below the surface. Various sherds of dark grey / black burnished bowls were also identified adjacent to this vessel. This structure was very poorly preserved in general, and no skeletal remains were recovered. The fact that there were no skeletal remains and the relatively smaller size of this pit also highlight the possibility that it may not be a grave but rather was used as a special deposition pit in relation to certain ritual activities within the cemetery. As explained below, similar features have also been identified elsewhere at the cemetery. On the other hand, various Early Bronze Age cemeteries in Ano Kouphonissi and Euboea, for example, had neither skeleton nor grave finds in some graves, whereas in a cemetery in Paros, 55 of the 131 graves yielded only pottery and no skeletal remains (Zapheiropoulou Reference Zapheiropoulou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008, 193).

Fig. 12. Plan of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 4. Drawing: Ramazan Güler.

Inventory of finds from Grave 4 (?)

-

BOY 00/10 (‘tripod jar with a spout’). The crudely made ‘tripod jar’ has a roughly globular body (Fig. 13). The spout of the jug is shaped in the form of a broad flaring rim. A vertically placed strap handle rises above the rim opposite the spout and joins the widest part of the body. Two of the three legs on which the jar rested are absent. The preserved foot of the tripod has a flat, rather than pointed, base. There are three crudely made knobs located below the rim: one on each side of the handle and another beneath the spout. The vessel is poorly fired and its biscuit has a thick black core. On the surface it has a reddish-brown slip (2.5 YR 5/3). The vessel is covered with a thick incrustation due to the character of the soil matrix in the area (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Cat. no. BOY 00/10. Tripod jar found in Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 4. Drawings: Douglas Faulmann. Photo: Chronis Papanikolopoulos.

Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 5

Grave 5 was excavated in test trench 10 during the 2005 campaign (Fig. 2). This is also a roughly circular pit dug into volcanic porous bedrock. The diameter of the grave is wider at the bottom (c. 1.25 m) but narrows towards the top (c. 1 m) (Fig. 14). Its preserved height is c. 0.80 m. Thus it can be argued that the upper part (roof) of the grave must have collapsed into the chamber itself. This grave presents important evidence that the grave pits 1 and 4 described above should also belong to rock-cut chamber tombs. The grave chamber contained a stone, which might have functioned as a ‘pillow slab’ as in Graves 1 and 2. Although it was rich in burial goods, there were no skeletal remains preserved in the grave. Grave 5 also included two jug-like pitchers (Fig. 15ab) and a pyxis with string-hole lugs (Fig. 15c) as grave goods.

Fig. 14. Photo, plan and section of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 5. Drawing: Ramazan Güler. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

Fig. 15. Cat. nos (a) BOY 05/01; (b) BOY 05/02; and (c) BOY 05/03. Pottery found in Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 5. Drawings: Douglas Faulmann. Photos: Chronis Papanikolopoulos.

Inventory of finds from Grave 5

-

BOY 05/01 (pitcher). The crudely made pitcher has one vertical strap handle rising above the rim and joining the lower part of the body. The opposite part of the mouth is higher and forms an open spout. Part of the rim is broken and there is also a hole created during the excavations on the upper part of the body. The oval bodied pitcher has a rounded base, which makes it impossible for the pot to stand upright. The fabric is medium coarse to coarse and has a black core in its biscuit. It has the same characteristics as other pottery examples from the cemetery. The vessel is mottled reddish-brown slipped (2.5 YR 5/6) on the outside and also on the higher part of the inner surface (Fig. 15a).

-

BOY 05/02 (pitcher). The crudely made pitcher has one vertical strap handle rising above the rim and joining the lower part of the body (Fig. 15b). It is larger but almost identical to BOY 05/01 in form. The oval shaped mouth is higher on the opposite side of the handle and forms an open spout. The fabric is medium coarse to coarse with a black core in its biscuit, and it seems identical to most of the other ceramic vessels from the cemetery. The pitcher is mottled brown slipped (7.5 YR 5/6), and burnished. The slip is also better preserved than that of BOY 05/01. This shape of pitcher/jug is not well documented in western Anatolian grave contexts.

-

BOY 05/03 (pyxis). The pyxis has no neck but the groove at the mouth of the vessel suggests the presence of a lid, which was not found during the excavations (Fig. 15c). It has a globular body and a round base. The vessel has eight alternately placed, vertically perforated lugs on the shoulder of the vessel. Four of the lugs are roughly square shaped, measuring 1.7 cm each. The other four alternate lugs are smaller and are shaped as rounded knobs. The pyxis has a much finer micaceous fabric different from the other ceramics in the cemetery. Its flaky fabric also contains fine black mineral inclusions and probably small pieces of grog. The vessel is covered with a red slip, which is heavily worn. The finer fabric and the red slip are reminiscent of the late EB II fine red slipped material well known around the Izmir region from Liman Tepe and Bakla Tepe (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Gillis and Sjöberg2008; Reference Şahoğluin press).

Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 6

The final grave excavated in Boyalık cemetery in 2005 is located in Trench 10, south of Grave 5 (Fig. 2). This grave is again a circular pit measuring c. 1.30 m in diameter cut into the volcanic porous bedrock and must also be a rock-cut chamber tomb (Fig. 16). The depth of the grave is c. 1.50 m from the present surface. The preservation of the grave is reminiscent of Grave 1. A vertical handled black burnished jug was encountered at c. 1.40 m from the surface. Underneath this find, at a lower level, bones and skulls belonging to multiple individuals were found. The skulls were located in the north-west, and the feet of the skeletal remains were at the north-eastern part of the grave chamber. The badly preserved skeletons were in a contracted position. A ‘pillow slab’ was also identified next to a skull as in some of the other graves in the cemetery.

Fig. 16. Photo and plan of Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 6. Drawing: Ramazan Güler. Photo: Hüseyin Vural.

Inventory of finds from Grave 6

-

BOY 05/04 (jug). The only find from Grave 6 was a jug with a globular body and a round base, which was placed next to the ‘pillow slab’ (Fig. 17). Most of its rim is missing, but judging from the shape, it must be a broad mouthed jug with a strap handle extending from the rim to the widest part of the body. The general morphology of the vessel also resembles an askos. The vessel is grey slipped and well burnished with a black and brown mottled surface (5 Y 2.5/1; 7.5 YR 4/4). The fabric is different from all the other examples in the cemetery and includes fine black mineral inclusions and fine dense white inclusions. The jug is relatively heavy and its fabric is reddish-brown clay with a grey core. Both the shape as well as the surface treatment of this vessel have similarities with ceramics dated to the late EB II period from sites like Liman Tepe and Çeşme–Bağlararası, also on the Urla Peninsula.

Fig. 17. Cat. no. BOY 05/04: jug found in Çeşme–Boyalık Grave 6. Drawing: Douglas Faulmann. Photo: Chronis Papanikolopoulos.

Other excavated features at the cemetery

Various other circular features cut into the bedrock were excavated at Boyalık cemetery that were dug and recorded as pits. Closer examination, however, highlights various details which may provide evidence to suggest that at least some of them were also rock-cut chamber tombs that were exposed to severe disturbance.

One of these circular pits (Pit 1) is located towards the south of test trench 6. This pit, cut into the volcanic porous bedrock, has a diameter of c. 1.80 m. It was excavated down to a depth of 1.50 m. At the depth of c. 1.20 m, a burned layer with a few coarse ceramic sherds was identified (Fig. 2).

Another circular pit cut into the bedrock was located at the western end of test trench 2 (Pit 2) (Fig. 2). The diameter of this pit expanded and reached 1 m as the excavations got deeper. The pit was excavated up to 1.80 m depth. In the end, no archaeological remains were discovered in this pit. But the widening of the pit diameter at the lower part clearly resembles the widening of a grave chamber, which might have been destroyed in ancient times.

Another circular pit cut into the bedrock was identified to the north-east of test trench 2 (Pit 3). The pit has a diameter of c. 1.30 m. The upper layers contained volcanic porous rubble, under which was a layer of soil that yielded shallow bowl fragments. The pit was excavated down to 1.50 m depth (Fig. 2). The ceramics found in this pit all belong to shallow bowls – a vessel type not attested in the graves (Fig. 18). Most of the sherds are dark grey / black in colour and are well burnished, demonstrating similarities with the surface treatment of the jug from Grave 6 (BOY 05/04) (Fig. 17). Their fabrics accord well with the characteristic Boyalık fabric with inclusions of organic temper, semi-transparent crystalline grains and white grains with sharp edges. Although the stone rich fill in the upper levels of this pit may suggest the collapsed roof of a chamber tomb, the nature of the finds recovered from it may also indicate a different kind of potentially collective ritual activity within the cemetery area – like feasting – related to mortuary rituals.

Fig. 18. Pottery fragments found in Pit 3 at Çeşme–Boyalık cemetery. Drawing: Douglas Faulmann.

Excavations in 2000 revealed a ‘channel’-like feature cut into the bedrock in the eastern part of test trench 2, close to Graves 1–3. This ‘channel’ extends in a north-east to south-west direction and measures c. 8 m in length and 1.2 m in width, having a depth of 0.20 m in the excavated part (Fig. 2). Various niches have also been identified on both sides of this corridor. This feature was dug and described as such by the excavators without any additional information. Judging from the dense concentration of the graves around test trench 2, we can speculate that this ‘channel’ might have been a long dromos and the niches might have led to stomia of various rock-cut chamber tombs on both sides of this path. A similar idea can be seen at a later Middle Bronze Age pithos cemetery in inland western Anatolia, at Afyon–Dede Mezarı cemetery (Üyümez, Koçak and İlyaslı Reference Üyümez, Koçak and İlyaslı2008, 406, drawing 2, photo 7).

The available data at hand suggests that the rest of the cemetery extended further east beneath the newly constructed villas and is now most probably totally destroyed by modern construction.

BURIAL PRACTICES AT ÇEŞME–BOYALIK CEMETERY

The rescue excavations at Çeşme–Boyalık extramural cemetery have, for the first time, demonstrated the existence of rock-cut chamber tombs in coastal western Anatolia during the third millennium BC. The best-preserved example (Grave 2) (Figs 7, 8 and 9) indicates that the graves have a roughly circular burial chamber cut into volcanic porous bedrock with a domed roof and accessed from the dromos through a stomion blocked with an upright stone slab. The evidence from Grave 2, where a pithos burial located in the dromos adjacent to the stomion was found, clearly indicates the final usage of the grave chamber. Other tombs (Graves 1, 5 and 6) were discovered without a roof. However, their similarity in shape to Grave 2, the expanding diameter of the grave chamber as it gets deeper in Grave 5 and layers of rocky rubble above the burials in these pits can be considered as evidence for evaluating these graves to be rock-cut chamber tombs. Nevertheless, even if they can be interpreted as rock-cut pit graves, this interpretation also makes them unique, as no such grave type exists in western Anatolian burial habits. The size of the grave chambers at Boyalık measures approximately 1.30–1.70 m in diameter with a height of at least c. 0.80 m. Only one stomion was discovered (Grave 2), which opens towards the west / north-west.

Unfortunately, we do not have detailed information regarding the burial postures due to the bad preservation of skeletal material as well as a lack of high-resolution documentation during the excavations. Some of the graves include multiple burials, which is usual for rock-cut chamber tombs. In light of the present evidence, the highest number of individuals in one grave is three (Grave 3). In general, it can be postulated that the skulls were placed in the west / north-west and the feet were extending towards the east / south-east.

One important aspect seen in almost all the graves is the ‘pillow stone’, which in all cases was found next to one of the skulls – presumably the skull of the final burial in the grave. This is a slab stone, which must have been used as a ‘pillow’ according to the burial traditions of the time. Similar examples have been found in the Cyclades, especially at the cemetery of Ayioi Anargyroi at Naxos dating to the Kampos Phase (Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 51–2, fig. 22). At least three of the Keros-Syros Culture tombs at Chalandriani in Syros included slab stones, which must have been used as ‘pillow stones’ (Hekman Reference Hekman2003, 81). Other sites like Ayios Kosmas in Attica (Mylonas Reference Mylonas1959; Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 66) and Manika in Euboea (Sampson Reference Sampson1985; Reference Sampson1988), which display Cycladic Kampos Group affinities, also have evidence for slab stones used as ‘pillow stones’ in the graves. The fact that this feature also exists in the Chios–Emporio tomb as well (Hood Reference Hood1981, fig. 82) may be a strong indication that it is part of the common burial tradition of the central Aegean region covering an area extending from Euboea and Attica towards the eastern Aegean.

At least some of the jugs in Boyalık burials seem to have been placed adjacent to the skull and the ‘pillow stone’, as can be clearly seen in Grave 6. The fact that two beak-spouted jugs from Graves 1 and 2 were found at higher elevations in the grave chambers might mean that there were repeated rituals involving liquids performed during and after the burial process where the jug was left in the grave upon their completion.

Various other features excavated within the investigated area may point to certain other ritual practices at the cemetery. Pit 2, cut into the bedrock within the cemetery (Fig. 2), probably represents another burial chamber that was extensively disturbed in the past. The feature identified as Grave 4 (?), for example, yielded no skeletal data and included a tripod jar with an open spout along with some dark burnished bowl fragments. Pit 1 included a burnt layer with broken pottery, and Pit 3 included many dark burnished bowl fragments (Fig. 18) in contrast to the predominantly pouring vessel types found within the graves. The evidence from these three features may be an indication for various ritual activities taking place within the Boyalık cemetery similar to the evidence for funerary or post-funerary ceremonies in cemeteries like Tsepi-Marathon in Attica, where a large rectangular pit of late Early Helladic (EH) I date was filled with intentionally broken pottery, sometimes associated with animal remains and many stones. The stones in this assemblage were thought to have been thrown into the pit for smashing the vessels (Pantalidou Gofa Reference Pantalidou Gofa2005). The late Early Cycladic (EC) I cemetery at Ayioi Anargyroi in Naxos provided evidence for a stone paved platform with hat-like vessels closely associated with it (Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 63–4). A number of pits belonging to the EC II–III periods were discovered in Rivari cemetery in Milos, which have been interpreted as evidence of a ritual involving the purification and removal of artefacts (Televantou Reference Televantou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008). These pit deposits seem to include the contents of the earlier tombs, including human bones, and were covered with tuff rubble (Televantou Reference Televantou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008, 214). The covering of the ceremonial pits with a tuff rubble in Rivari may be similar to the evidence from Boyalık Grave 4 (?) and Pit 3 contexts where a layer of broken pottery is also sealed with volcanic porous rubble. Another similar context indicating a special deposit that may be connected to the nearby cemetery has been excavated at Bakla Tepe, dating to the late EB II period (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016).

The ‘channel’ at Boyalık cemetery with niches on both sides is another unique feature whose original function unfortunately could not be confirmed. But as explained above, there is a possibility that it could have functioned as a pathway leading to the entrances of various rock-cut chamber tombs that were situated on its sides, as in Afyon–Dede Mezarı cemetery of a later Middle Bronze Age date with pithos burials (Üyümez, Koçak and İlyaslı Reference Üyümez, Koçak and İlyaslı2008, 406, drawing 2, photo 7).

DATING THE ÇEŞME–BOYALIK CEMETERY

The grave goods at Boyalık do not display much variation. Ceramic vessels comprise the main group of finds. All pots are handmade. All but a few have a uniform medium coarse fabric with organic inclusions as well as semi-transparent crystalline grains and white mineral grains with sharp edges. All of the ceramics in the graves belong to pouring vessels with the exception of the two pyxides. Some vessel shapes like BOY 05/01 and 05/02 (pitchers; Fig. 15ab) from Grave 5 seem to be unique so far with no exact parallels around this region. A somewhat similar shape can be cited from Hacılartepe from north-west Anatolia dating to an earlier EB II phase (Eimermann Reference Eimermann2004, fig. 4:8). The beak-spouted jugs have close parallels at the cemeteries of Yortan (Kamil Reference Kamil1982, 94, shape VIII, pl. VIII, figs 38–9, 43–4), Demircihöyük Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000, fig. 18:G.38b), Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991, fig. 10:4) and Hacılartepe (Eimermann Reference Eimermann2004, fig. 7:6). One of the pyxides (BOY 05/03) seems to be unique in terms of its fully spherical shape and eight lugs on its shoulder. Its fabric and surface treatment, on the other hand, belong to a special ware group well known in the Izmir region, especially from Liman Tepe and Bakla Tepe. This distinctive fine micaceous ware group, with applied red wash slip, appears for the first time during the earlier part of the late EB II in the Izmir region and is a distinctive element of this period (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Gillis and Sjöberg2008, 159–60; Reference Şahoğluin press). The incised pyxis (BOY 00/07) also belongs to a distinctive type that appears among western Anatolian grave contexts of the EB II–III periods. Similar flat-based or tripod variations of this shape also display a wide distribution at cemeteries like Yortan (Kamil Reference Kamil1982, 83, shape II, pl. IV, figs 25–7), Demircihöyük Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000, fig. 37i), Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991, fig. 7:1,3) and Kumyer (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013, fig. 144:1–2). A very similar pyxis is also known from Mordoğan (Bittel 1938–41, 21, fig. 18) in the Urla Peninsula, not far from Boyalık.

The silver ram pendant (BOY 00/09) (Fig. 11b) from Grave 2 constitutes a unique find with only a few parallels around the Aegean. An exact parallel of this ram pendant comes from a pithos grave (69.3) of late EB II date from Eski Balıkhane near the Gygean Lake, 2 km to the east of Ahlatlı Tepecik near Sardis – an area not too far from Izmir (Mitten and Yüğrüm Reference Mitten and Yüğrüm1971, 192–4; Mitten Reference Mitten and Simpson2018, pl. 6:6). The Eski Balıkhane example is also of silver and has a string-hole as well. It was found in between the teeth of the skull resting in the grave, further suggesting its use as a pendant. The context of the Eski Balıkhane pithos grave also includes two black burnished jugs (one of them with a similar arrangement of knobs on the shoulder) and a form defined as ‘tankard’ in the publications – which does not conform to the usual nomenclature of how a tankard is defined in western Anatolia.Footnote 3 Apart from these jugs, a copper dagger and two gold-plated ear plugs (Mitten and Yüğrüm Reference Mitten and Yüğrüm1971, figs 4, 5, 6, 7; Mitten Reference Mitten and Simpson2018, 118, pl. 6:7) formed part of the grave inventory.

Two other similar examples of zoomorphic pendants, one in silver and another in copper, were found within rock-cut chamber tomb no. 200 at Hagia Photia cemetery in northern Crete (Davaras and Betancourt Reference Davaras and Betancourt2004, 180–2, fig. 448:220.22a,200.22b). The silver one depicts a ram and displays all the details observed on the Boyalık and Eski Balıkhane pendants (Giumlia-Mair, Betancourt and Ferrence Reference Giumlia-Mair, Betancourt, Ferrence, Giumlia-Mair and Lo Schiavo2018, 530, fig. 9). Tomb 200 has a circular anteroom and a grave chamber, which included four burials with 13 vases, eight metal objects, including the silver pendant, and four obsidian blades. The grave context predominantly reflects characteristic Cycladic Kampos Group material like the rest of the cemetery.

Another small lead ram figurine which is currently housed at the Goulandris Museum is of unknown provenance (Stampolidis and Sotirakopoulou Reference Stampolidis and Sotirakopoulou2007, 206–7, cat. no. 64). This example can be considered a figurine, rather than a pendant, as it lacks the string hole. Two additional unprovenanced lead examples of small ram figurines of the same type are mentioned in the publication as belonging to private collections (Stampolidis and Sotirakopoulou Reference Stampolidis and Sotirakopoulou2007, 206). At the settlement of Karataş–Semayük in south-western Anatolia, a silver toggle pin with an animal head (representing a boar and dating to late EB II) is very different in form but remains significant due to the scarcity of silver animal representations from the Aegean and western Anatolian regions during this period (Mellink Reference Mellink1970a, 248, fig. 16ab; Mellink Reference Mellink1970b, 137, fig. 7; Warner Reference Warner1994, 113, 180, pl. 189b).

Other finds from the Boyalık graves include a bronze spiral ring (Fig. 5d), a spindle whorl (Fig. 5c) and an obsidian blade (Fig. 11c). Similar bronze spiral rings with flattened ends are also well known in western Anatolian grave contexts of late EB II date. Numerous examples were found in pithos burials of the EB II period including the Demircihöyük Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000, Grave 323, p. 155, ill. 39ab) and the Küçükhöyük cemeteries in inland western Anatolia (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991, abb. 23:7–21, pl. 15:7). Similar finds are also known from the late EB II period from Kumyer cemetery in coastal south-western Anatolia (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013, 430, fig. 164, 436, fig. 170).

Biconical incised spindle whorls are also a characteristic type of grave good in western Anatolian extramural cemeteries of the third millennium BC. Similar examples can be seen at Yortan (Kamil Reference Kamil1982, 21, figs 85–6), Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991, ill. 24–5), Kumyer (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013, figs 136:3, 138:2–3) and Demircihöyük cemeteries (cf. Seeher Reference Seeher2000, ill. 19, 21, 22 and 25). Obsidian blades are not typical grave goods in coastal western Anatolian burial assemblages but nevertheless, in some cases, can be found in certain burials, as in Kumyer cemetery Grave 78 (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013, fig. 92:2).

The grave finds unearthed at Boyalık cemetery do not reflect any similarities with grave assemblages from the Cyclades, Greek mainland or Crete, except for the single obsidian find believed to be of Melian origin and the silver ram pendant, which has a very similar parallel from the cemetery at Hagia Photia in Crete (Davaras and Betancourt Reference Davaras and Betancourt2004, 180–2, fig. 448:220.22a,200.22b) that is dated to Early Minoan IB (the Kampos phase of the Cyclades).

The fact that almost none of the characteristic pottery shapes (namely tankards, bell-shaped cups, tea-pots, cut away spouted jugs or later depas types) found in the late-EB-II- and early-EB-III-period cemeteries of western Anatolia are present at Çeşme–Boyalık suggests that the Boyalık graves most probably belong to a period slightly earlier than the developed stage of the late EB II in western Anatolia. The typological characteristics of the jugs and the incised pyxis can be compared to similar examples from the EB II cemeteries in western Anatolia. The globular pyxis (BOY 05/03) probably represents one of the earliest examples of the fine micaceous red washed ware, which is a characteristic new ware group that defines the beginning of the late EB II period around the Izmir region (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Gillis and Sjöberg2008, 159–60; Reference Şahoğluin press). The pottery from Boyalık cemetery helps us to date the cemetery to a time range extending from the EB II to the earlier part of the late EB II period of western Anatolia.

A GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE AEGEAN GRAVE TYPES DURING THE THIRD MILLENNIUM BC

Burial practices are one of the most indicative and strong manifestations of cultural traits. Aegean burial practices of the third millennium BC are part of a dynamic process that reflects regional variations in time and space. The most characteristic grave types of the Early Bronze Age Aegean are cist graves, pithos graves, simple pit burials and rock-cut chamber tombs that display a certain distribution pattern around the Aegean mainland and the Cyclades. Although Crete shares certain common aspects as a result of its socio-economic and political connections with the rest of the Aegean, it reflects a different picture in general.

Cist graves

Cist graves form the main grave type around the Cyclades during the EC I period (Doumas Reference Doumas1977). This is a tradition that finds its roots already in the Kephala Culture of the region (Coleman Reference Coleman1977) and shows continuity in time. Aghios Kosmas (Mylonas Reference Mylonas1959) and Tsepi Marathon in Attica also possess cist graves (Pantalidou Gofa Reference Pantalidou Gofa2005). This grave type continues to be the distinctive form of burial around the Cyclades during the Keros-Syros Culture (EC IIA period). During this period, there is a general increase in the number of graves within cemeteries, and Chalandriani at Syros represents the summit of this increase with more than 500 graves (Hekman Reference Hekman2003; Renfrew Reference Renfrew2011, 179). Chalandriani in Syros and graves in some other Cycladic islands also possess another grave type built with dry stone walling. These have been termed ‘corbelled graves’ (Renfrew Reference Renfrew2011, 179; Broodbank Reference Broodbank2000, 199–200). With the end of the traditional Cycladic Culture by the end of the Keros-Syros Phase, this burial tradition also tends to fade away.

Iasos cemetery in coastal western Anatolia also yielded cist graves similar to Cycladic examples with pottery which can be compared to Kampos Group types (Pacorella Reference Pacorella1984). Further north, Bakla Tepe in the Izmir region reflects a different picture during the EB I period with a cemetery including cist, pithos and simple pit graves being used contemporaneously (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016). Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991) and Demircihöyük Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000) possess evidence for the use of stone cist graves along with pithos and simple pit burials (at Demircihöyük Sarıket) during the following EB II period.

Pithos graves

Burial in pithos containers is the traditional burial practice of western Anatolia from at least the beginning of the third millennium onwards (Massa and Şahoğlu Reference Massa, Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011; Stech-Wheeler Reference Stech-Wheeler1974). Intramural infant jar burials are already known at Late Chalcolithic Bakla Tepe (Erkanal and Özkan Reference Erkanal, Özkan, Özkan and Erkanal1999, 134). Extramural pithos graves have been found at Bakla Tepe alongside cist and simple pit burials during the western Anatolian EB I period. Pithos graves dominate the burial tradition of western Anatolia during the following EB II and III periods as can be evidenced at extramural cemeteries like Yortan (Kamil Reference Kamil1982), Babaköy (Bittel Reference Bittel1939–41), Küçükhöyük (Gürkan and Seeher Reference Gürkan and Seeher1991), Demircihöyük Sarıket (Seeher Reference Seeher2000), Bakla Tepe (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016), Kumyer (Akarsu Reference Akarsu2013), Çapalıbağ (Oğuzhanoğlu and Pazarcı Reference Oğuzhanoğlu and Pazarcı2020), Kesikservi (Aykurt et al. Reference Aykurt, Böyükulusoy, Benli-Bağcı and Deniz2023), Gündürle Harmanören (Özsait Reference Özsait2000) and Karataş–Semayük (Stech-Wheeler Reference Stech-Wheeler1974). Pithos graves are very few in number in the southern and western Aegean where they are clearly not at home.

Simple pit burials

Simple pit burials are one of the typical burial types of western Anatolia during the third millennium BC. This type is attested at the EB I cemetery of Bakla Tepe along with cist and pithos graves (Massa and Şahoğlu Reference Massa, Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011; Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Pernicka, Ünlüsoy and Blum2016). Demircihöyük Sarıket cemetery in inland western Anatolia also possesses simple pit burials along with cist and pithos graves during the following EB II period (Seeher Reference Seeher2000; Massa Reference Massa2014). Simple pits are also found at settlements sometimes including infant burials.

Rock-cut chamber tombs

Rock-cut chamber tombs of the third-millennium Aegean have previously been discussed in detail in various publications (Cultraro Reference Cultraro2000; Sapouna-Sakellarakis Reference Sapouna-Sakellarakis1987; Sotirakopoulou Reference Sotirakopoulou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008). Among them, important evidence comes from those found at Agrilia–Ano Kouphonisi (Zapheiropoulou Reference Zapheiropoulou1983; Reference Zapheiropoulou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008), Phylakopi–Melos (Edgar Reference Edgar1897; Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou1965, 513), Rivari–Melos (Televantou Reference Televantou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008) and Akrotiri–Thera (Doumas Reference Doumas, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008)Footnote 4 on the Cyclades, Manika (Papavasileiou Reference Papavasileiou1910, 2–20; Sampson Reference Sampson1985, 153–316; 1988) and Kephisos (Athens) (Asimakou Reference Asimakou, Mathari, Renfrew and Boyd2019) on mainland Greece, Aghia Photia (Davaras and Betancourt Reference Davaras and Betancourt2004; Betancourt Reference Betancourt, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008) on Crete, and Emporio in Chios (Hood Reference Hood1981, 150–2, fig. 82).

The extensive cemetery of Manika in Euboea (Sampson Reference Sampson1985; Reference Sampson1988; Sapouna-Sakellarakis Reference Sapouna-Sakellarakis1987) has rock-cut chamber tombs with Cycladic affinities during the later phases of the EH I period. The Manika cemetery continues to be used into the ‘Lefkandi I’ period (Sampson Reference Sampson1985; Reference Sampson1988; Sapouna-Sakellarakis Reference Sapouna-Sakellarakis1987, 256). Burials at Kephisos–Aegaleo in Attica on the Greek mainland also possess similar rock-cut chamber tombs which date to the late EH I (Cycladic Kampos) phase (Asimakou Reference Asimakou, Mathari, Renfrew and Boyd2019). Various other cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs were found at sites like Corinth or Lithares on the Greek mainland and have been discussed by Sapouna-Sakellarakis (Reference Sapouna-Sakellarakis1987, 258–9).

Agrilia and two other cemeteries in Ano Kouphonissi seem to be the only known cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs dating to the first half of the third millennium BC around the Cyclades. These cemeteries belong to the Kampos Phase of the EC I period (Zapheiropoulou Reference Zapheiropoulou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008). An exceptionally similar type of cemetery of the same date has also been investigated at Aghia Photia on the northern coast of east Crete (Davaras and Betancourt Reference Davaras and Betancourt2004). Both of these cemeteries yielded a certain type of rock-cut chamber tomb with a dromos and a grave chamber with a stone slab blocking the stomion.Footnote 5 The unique connection between these two cemeteries is discussed in detail by Broodbank (Reference Broodbank2000, 300–4). Rivari at Melos in the Cyclades also has rock-cut chamber tombs, which are dated to the EC II–III periods (Televantou Reference Televantou, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008). Various other rock-cut chamber tombs at Melos were unfortunately not properly excavated and were mainly plundered, making accurate dating impossible (Edgar Reference Edgar1897; Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou1965, 513; Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 49). They are, nevertheless, generally dated to the ‘Phylakopi I’ phase (EC III) (Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 49, 53). Rock-cut chamber tombs at Akrotiri on Thera are also dated to the EC II–III periods. A rock-cut chamber tomb at Emporio on Chios in the eastern Aegean is also dated to the EB II period (Hood Reference Hood1981, 150–2, fig. 82). The rock-cut chamber tomb is a unique burial type with a peculiar distribution pattern in terms of time and space around the Aegean. Lack of research must be the primary reason for the patchy picture that is evidenced for this particular type of burial.

Except for some distinct cemetery data mentioned above (Betancourt Reference Betancourt, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008; Davaras and Betancourt Reference Davaras and Betancourt2004; Day, Wilson and Kiriatzi Reference Day, Wilson, Kiriatzi and Branigan1998), Crete generally displays a different picture from the rest of the Aegean in terms of burial practices throughout the third millennium BC. The most characteristic grave types of the island include tholos graves and house tombs, although various cases of cave burials, larnax pithos, and cist burials are also noted (Branigan Reference Branigan1970; Herrero Reference Herrero2014; Papadatos Reference Papadatos2005; Soles Reference Soles1992; Vavouranakis Reference Vavouranakis and Vavouranakis2011). Cyprus is another place where rock-cut chamber tombs constitute an important place within the island's burial traditions. Burying the dead in rock-cut shaft graves was in practice during the Cypriot Middle Chalcolithic Period at Souskiou-Vathyrkakas (Peltenburg Reference Peltenburg2006) and Souskiou-Laona (Peltenburg, Bolger and Crewe Reference Peltenburg, Bolger and Crewe2019) in western Cyprus. Starting from the Late Chalcolithic and especially with the beginning of the Philia phase, as evidenced at Kissonerga Mosphilia (Peltenburg Reference Peltenburg1998) and other cemeteries like Vasilia on the northern coast of the island (Hennessy, Eriksson and Kehrberg Reference Hennessy, Eriksson and Kehrberg1988), rock-cut chamber tombs of the Çeşme–Boyalık type also began to appear in the island as a part of new cultural elements that are related to the Anatolian connections of Cyprus (Webb and Frankel Reference Webb and Frankel1999) during the Anatolian Trade Network period.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The discovery of an extramural cemetery with a rock-cut chamber tomb tradition at Çeşme–Boyalık is unique and adds a new perspective to our understanding of the burial practices in central coastal western Anatolia / eastern Aegean and particularly around the Urla Peninsula during the third millennium BC. The rock-cut chamber tombs of the third millennium BC on the Greek mainland and Crete are usually considered to be part of cemeteries with strong Cycladic affinities, especially in terms of the grave goods found in them. Çeşme–Boyalık cemetery, on the other hand, is so far unique in the western Anatolian coastline in terms of its grave type. In contrast to this assumed Cycladic character of the grave types, the grave goods reflect almost no affinities with the Cyclades except for the obsidian blade, which must have come from Melos, and the silver ram pendant, which is closely paralleled with the example from Aghia Photia cemetery in Crete. On the contrary, the pottery from the Boyalık graves seems to have very close parallels with other cemeteries around western Anatolia.

Due to massive modern construction in the entire area, no nearby settlement of this period is known to date. The closest systematically investigated settlement is Çeşme–Bağlararası, which is located at the centre of Çeşme, approximately 2.5 km west of Boyalık cemetery (Şahoğlu et al. Reference Şahoğlu, Çayır, Gündoğan and Tuğcu2018; Şahoğlu, Çayır and Gündoğan Reference Şahoğlu, Çayır, Gündoğan, Vitale and Marketouin press). Çeşme–Bağlararası is a coastal settlement dating to the middle of the third millennium BC. The site reflects a characteristic coastal western Anatolian settlement model that fits the ‘Aegean Settlement Pattern’ (Gündoğan Reference Gündoğan2020). As no burials have been found within the excavated settlement, there is a strong possibility that Çeşme–Bağlararası also has an extramural cemetery as in all the other western Anatolian Early Bronze Age settlements. Although Boyalık cemetery is located in close proximity to Bağlararası, it should have its own settlement, which is most probably lost forever due to heavy modern construction in that area, and Bağlararası should have its extramural cemetery at a much closer location to the site. Çeşme–Bağlararası reflects a local coastal settlement during this period with little maritime connections with the western Aegean (Şahoğlu et al. Reference Şahoğlu, Çayır, Gündoğan and Tuğcu2018; Şahoğlu, Çayır and Gündoğan Reference Şahoğlu, Çayır, Gündoğan, Vitale and Marketouin press) – an interesting aspect also reflected at Boyalık cemetery, as highlighted above.

One of the most important reasons behind the more local character of this area during the middle of the third millennium BC must be sought in the specific geographic location of the region and the navigation routes of the Aegean Sea based on the maritime technologies of the period. In a world without sails, the western tip of Urla Peninsula is one of the most difficult and dangerous areas to be navigated in the Aegean Sea. Liman Tepe, which is situated at the northern end of the narrowest land point of the Urla Peninsula joining the southern to the northern Aegean Sea – c. 60 km from Bağlararası and Boyalık – seems to be a major maritime hub during this period (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu2005; Reference Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu, Şevketoğlu and Erbil2019). A probable cartage route joining the two seas ending at Liman Tepe in the north must have accelerated the importance of this site during this period (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu2005, fig. 1b). As a result of the difficulty of navigating the rough Aegean Sea with the longboats of the period, Çeşme–Bağlararası and Boyalık, areas with little resources to offer, were most probably ignored and excluded from the maritime networks of the period. This seems to be the reason for the local characters of the sites at the western tip of the Urla Peninsula. The data from the Boyalık cemetery and nearby settlement at Çeşme–Bağlararası are now giving us a different picture of the socio-economic dynamics and micro-regional differences around the western Anatolian coastline that are triggered through geographical locations and technological advances in maritime mobility.

The dating of the Boyalık cemetery also makes it unique among the known cemeteries of the eastern Aegean coastline. In light of the grave goods, the cemetery can be dated to an advanced stage of the EB II period, around the beginning of the late EB II, c. 2600/2500 BC. This period also marks the first manifestation of the Anatolian Trade Network (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu2005; Reference Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu, Şevketoğlu and Erbil2019) on the central western Anatolian coastline, highlighting the importance of the Izmir region and particularly the Urla Peninsula as a gateway, integrating the inland cultural elements of Anatolia with those of the Aegean and beyond. The cemetery at Çeşme–Boyalık can be dated to the earlier phase of the Anatolian Trade Network. The presence of rock-cut chamber tombs in Çeşme–Boyalık and the singular example at Chios–Emporio clearly represent the presence of this tradition around the central eastern Aegean zone around this time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Excavations at Çeşme–Boyalık Early Bronze Age cemetery were carried out by archaeologist Hüseyin Vural as part of the rescue work undertaken by the Çeşme Archaeological Museum in 2000 and 2005. I would like to extend my gratitude to him for sharing his documentation of the excavations with me. I would also like to thank the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Turkish Republic for the permit to study this material. I would further like to extend my thanks to INSTAP and INSTAP–SCEC publication team members Douglas Faulmann and Chronis Papanikolopoulos for their amazing work in documenting the finds. My students and colleagues Dr Ümit Gündoğan and Ramazan Güler kindly contributed to the preparation of the maps and the re-drawings of the graves used. I am grateful for their efforts. I would like to thank Dr Evangelia Kiriatzi and Dr Rıza Tuncel for their valuable comments on the earlier versions of this work and also Ash Rennie for his proofreading on the English text and Dr Ourania Kouka for her translation of the abstract into Greek. The study of the finds from Çeşme–Boyalık cemetery has been carried out as part of our long-term archaeological investigations within the framework of the Izmir Region Excavations and Research Project (IRERP) of Ankara University Mustafa V. Koç Research Center for Maritime Archaeology (ANKÜSAM), which was initiated by the late Prof. Dr Hayat Erkanal.