INTRODUCTION

This paper investigates new evidence concerning braziers in terms of their provenance, typology, and distribution, offering a socio-economic interpretation supported by archaeological and historical data. The collection of braziers studied here was excavated in the Agora of Nea Paphos under the direction of Prof. E. Papuci-Władyka from the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. The result of several excavation seasons (2011–19) of the Paphos Agora Project (PAP) provided a large amount of data.Footnote 1 This allowed for a new interpretation of the functioning of the area in terms of changes in the economic infrastructure of the ancient city by evaluating the architecture of the Agora, the finds, and the use of landscape within the socio-economic and administrative context of the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Papuci-Władyka and Machowski Reference Papuci-Władyka, Machowski and Balandier2016; Papuci-Władyka et al. Reference Papuci-Władyka, Machowski, Miszk, Biborski, Bodzek, Dobosz, Droste, Kajzer, Marzec, Nocoń, Rosińska-Balik and Wacławik2018; Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka2020a; Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka2020b). The excavations, so far, have produced a very large amount of systematically collected ceramic assemblages: tens of thousands of fragments of cooking pottery, tableware, and amphorae, including sets of whole vessels, and many other categories of artefacts. Amongst this, as is commonly found in Hellenistic contexts at such sites, brazier fragments are very scarce. Nevertheless, this collection is extremely diverse in terms of both fabrics and shapes. Two fragments of braziers from the Agora assemblage have already been published by the author; however, only information of general nature has been provided so far (Nocoń Reference Nocoń2020a, 309–10, pl. 106). In this paper, different methods were applied: macroscopic fabric identification, typological and chronological studies, regional approach, and consumption theory. The combination of these approaches and comparison with fabrics which had been previously documented in Nea Paphos provided systematic data and established valuable conclusions concerning some aspects of everyday life in ancient Nea Paphos.

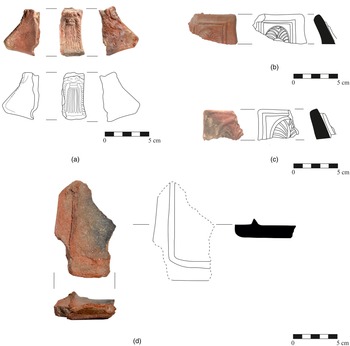

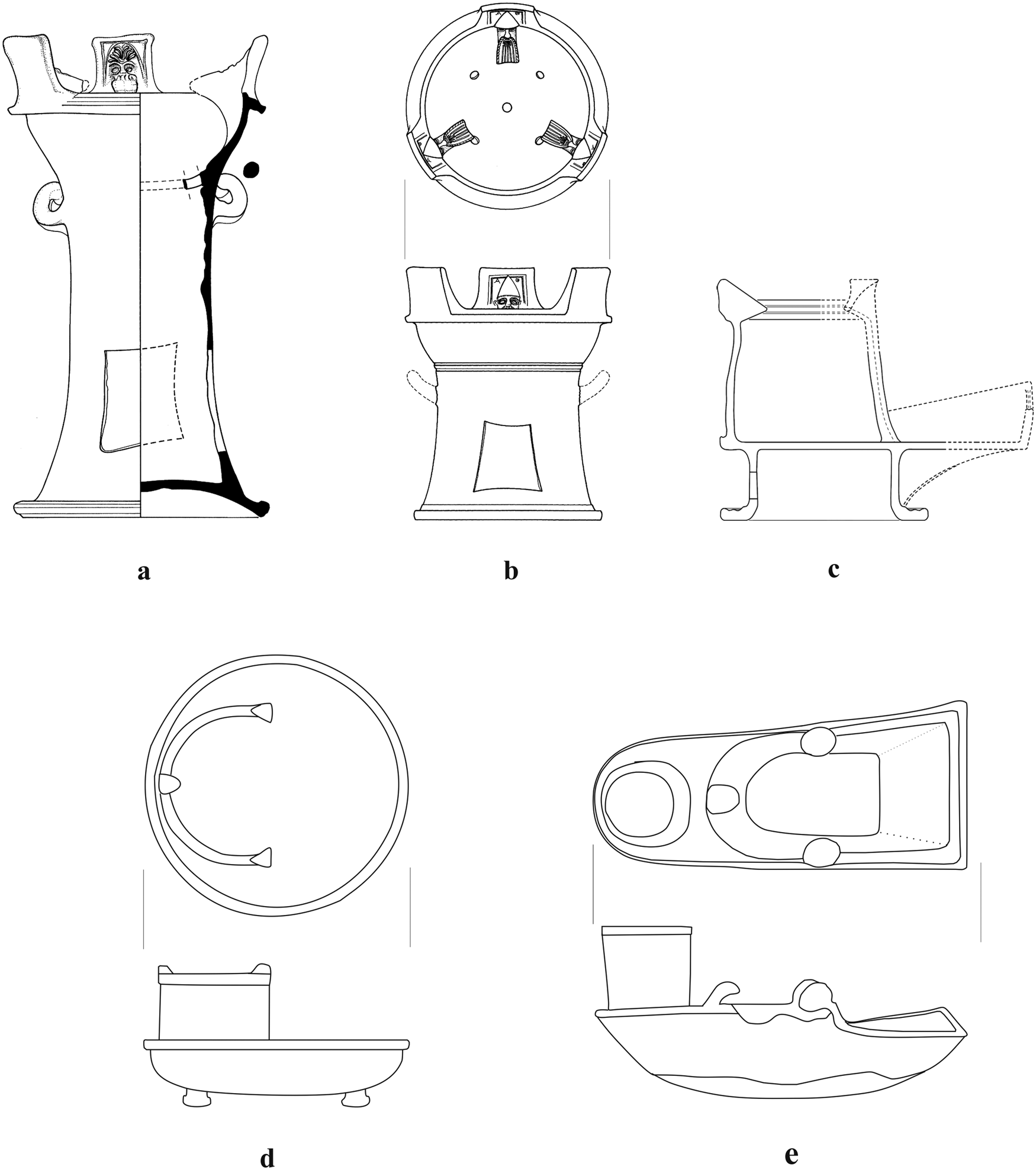

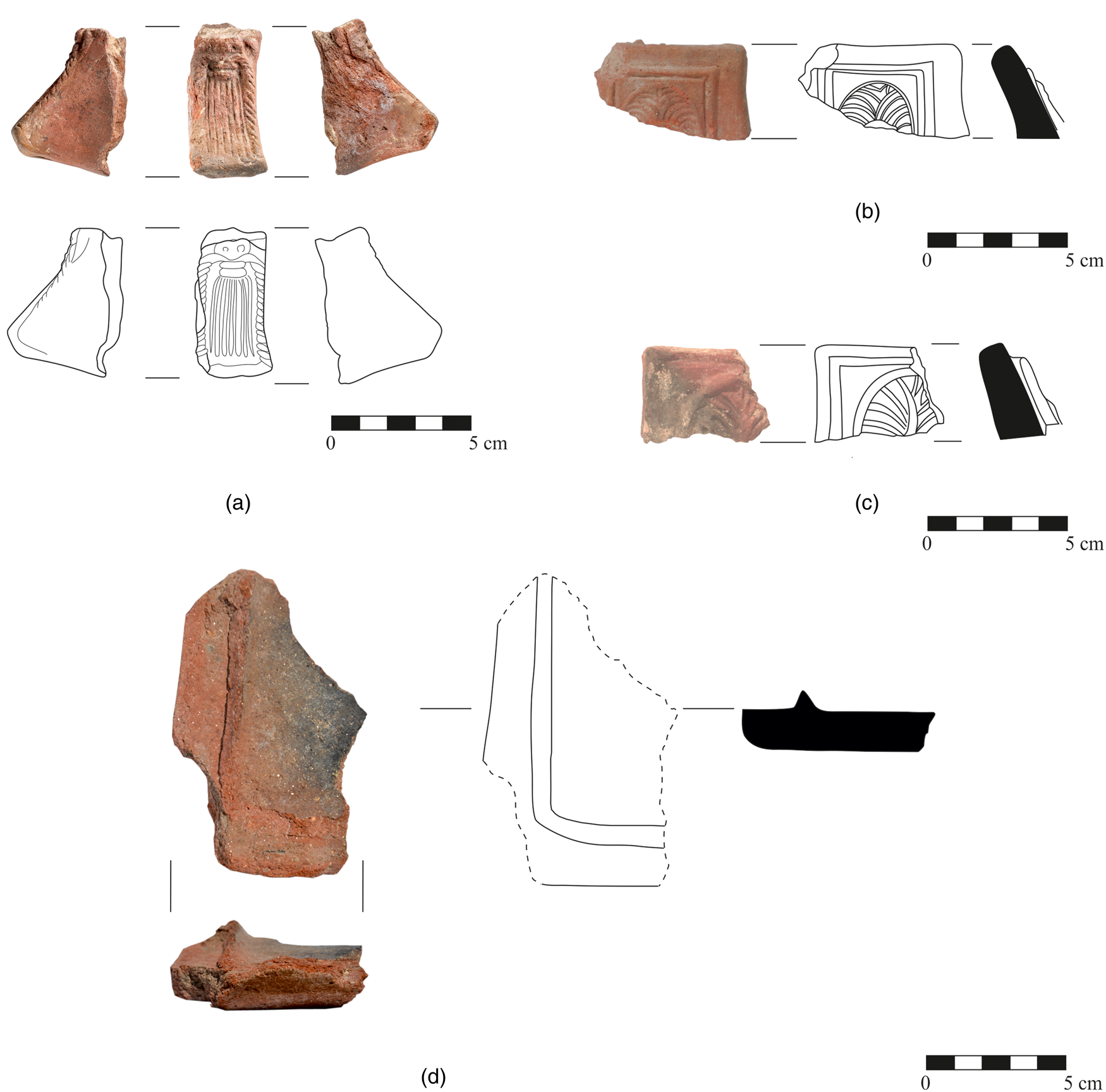

Portable braziers, made of clay utensils frequently connected to cooking processes, produced in different shapes (Fig. 1a–d),Footnote 2 were popular across the Mediterranean from the Early Hellenistic (EH) period to the Early Roman (ER) period. In recent years, braziers have received much attention in terms of provenance,Footnote 3 distribution,Footnote 4 and certain social behaviours associated with the manner and context of use,Footnote 5 which has allowed for an understanding of not only some aspects of everyday behaviour but also a broader view of certain cultural codes characteristic of a given community (Foxhall Reference Foxhall2007, 235–6, 240; Tsakirgis Reference Tsakirgis2007, 225, 228; Banducci Reference Banducci, Spataro and Villing2015, 157).

Fig. 1. Types of the Hellenistic braziers (a) with high stand and (b) low stand (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, figs 92:750, 94:786). (c) Brazier with tray (Rumscheid Reference Rumscheid, Delemen, Çokay-Kepçe and Özdizbay2008, 1089, fig. 15). (d) Early Roman brazier (Robinson Reference Robinson1959, 34–5, cat. no. G123, pl. 38). (e) Lead ship type brazier (based on Ashkenazi et al. Reference Ashkenazi, Fischer, Stern and Tal2012, 87, fig. 2).

Braziers found in the area of ancient Nea Paphos have been examined previously; however, a review of relevant literature revealed few studies regarding these artefacts. What we know about braziers is largely based on research undertaken by J.W. Hayes (Reference Hayes1991, 75–7) from his examination of the pottery assemblage from the House of Dionysos. This study was the first to classify the braziers of presumed Cypriot origin and identify the imports. Additional information has been provided by E. Papuci-Władyka (Reference Papuci-Władyka1995, 124–5, no. 135, pl. 22; Reference Papuci-Władyka, Ioannidis and Chatzistyllis2000, 735, pl. 7:5) from the Maloutena residential area and by F. Giudice (Reference Giudice1993, 297) from Garrison's Camp. However, although the presence of braziers of different provenance was demonstrated, little attention has been paid to the role of these artefacts in the society of ancient Nea Paphos.

METHODOLOGY

The methodological approach taken in this study is based on the macroscopic fabric examination of the many categories of pottery that occurred in the Agora (Marzec, Kajzer and Nocoń Reference Marzec, Kajzer and Nocoń2020) by adapting the procedure provided by Orton and Hughes (Reference Orton and Hughes2013, 277–82). Twenty-seven fragments of braziers were selected for this study, including fragments of attachments, handles, fire bowls, stands, and bases. The fragments of braziers were divided into macroscopic fabric groups based on certain features of the clay combined with their shape and chronology.

The first step in this process was to identify macroscopic fabric groups by using the following parameters: frequency, sphericity and roundness, size and colour of the inclusions; frequency, size, and shape of voids; surface treatment and colour of the external surface; hardness, feel of the surface and the character and colour of a fresh break. Additionally, the firing core types were identified. The colours were described using the Munsell Soil Color Charts (2013). The brazier fragments were examined macroscopically with the naked eye and with a 10x magnifying glass in natural light.

The second step was complemented by comparative studies and chronological analysis. The chronology of examined fragments was established on the basis of the typological parallels of individual examples and/or their chronological context (which was determined by the range between the earliest and latest fragments in the context). Thanks to the careful excavation most of the presented fragments were found in the well-stratified fill layers with a well-established chronology, spanning from the Late Hellenistic (LH) or ER periods (Miszk Reference Miszk2020). These steps resulted in the formation of the Braziers Macroscopic Groups (Br MGs). The final stage of the study aimed to establish the role of braziers in Hellenistic Nea Paphos. This was achieved by applying consumption theory (Albero Santacreu Reference Albero Santacreu2014, 195) to the historical and archaeological data.

RESULTS

The macroscopic examination resulted in the identification of seven Br MGs within the studied assemblage. The general descriptions of the macroscopic groups are presented in Table 1, while the catalogue of fragments belonging to the groups is presented in Table 2. Groups are discussed in the following order: discussion of fabric provenance, followed by chronological and typological analyses of fragments.

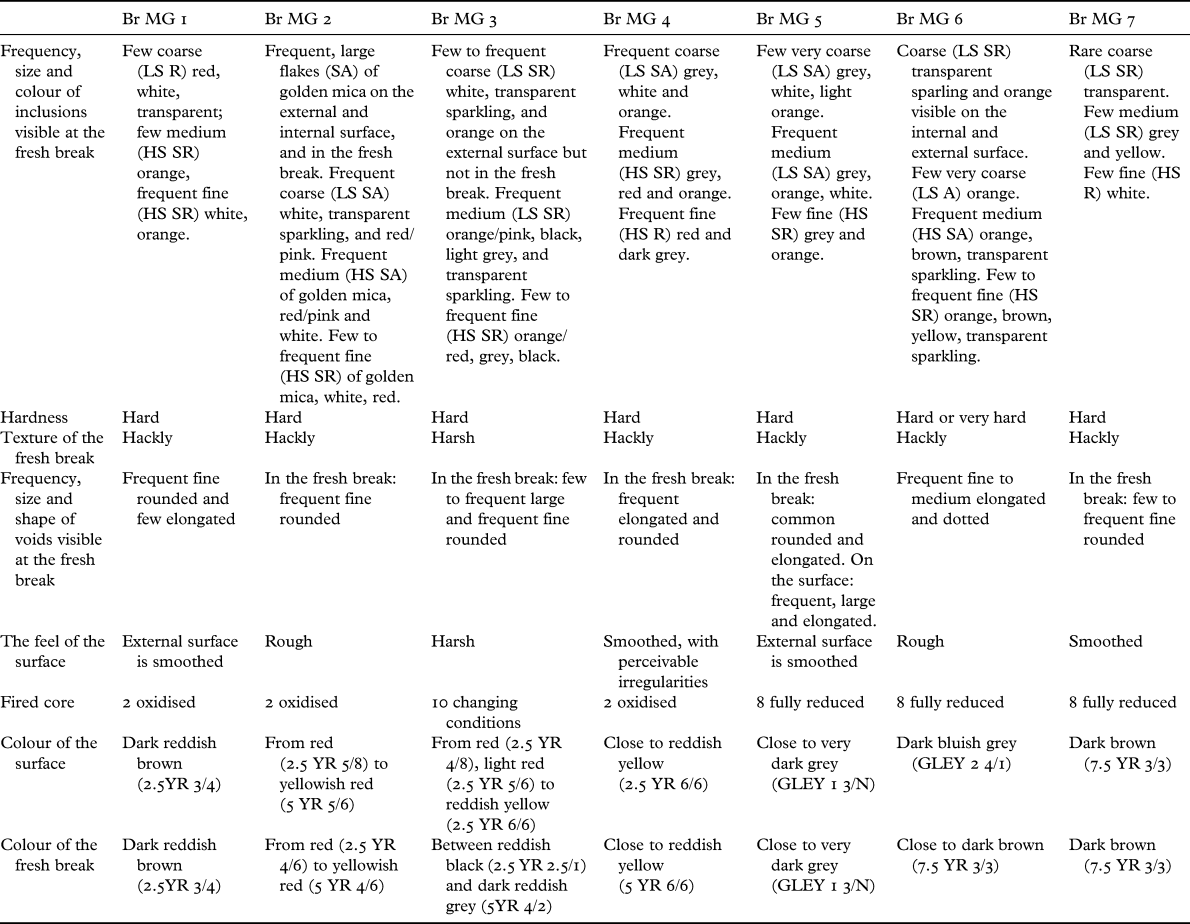

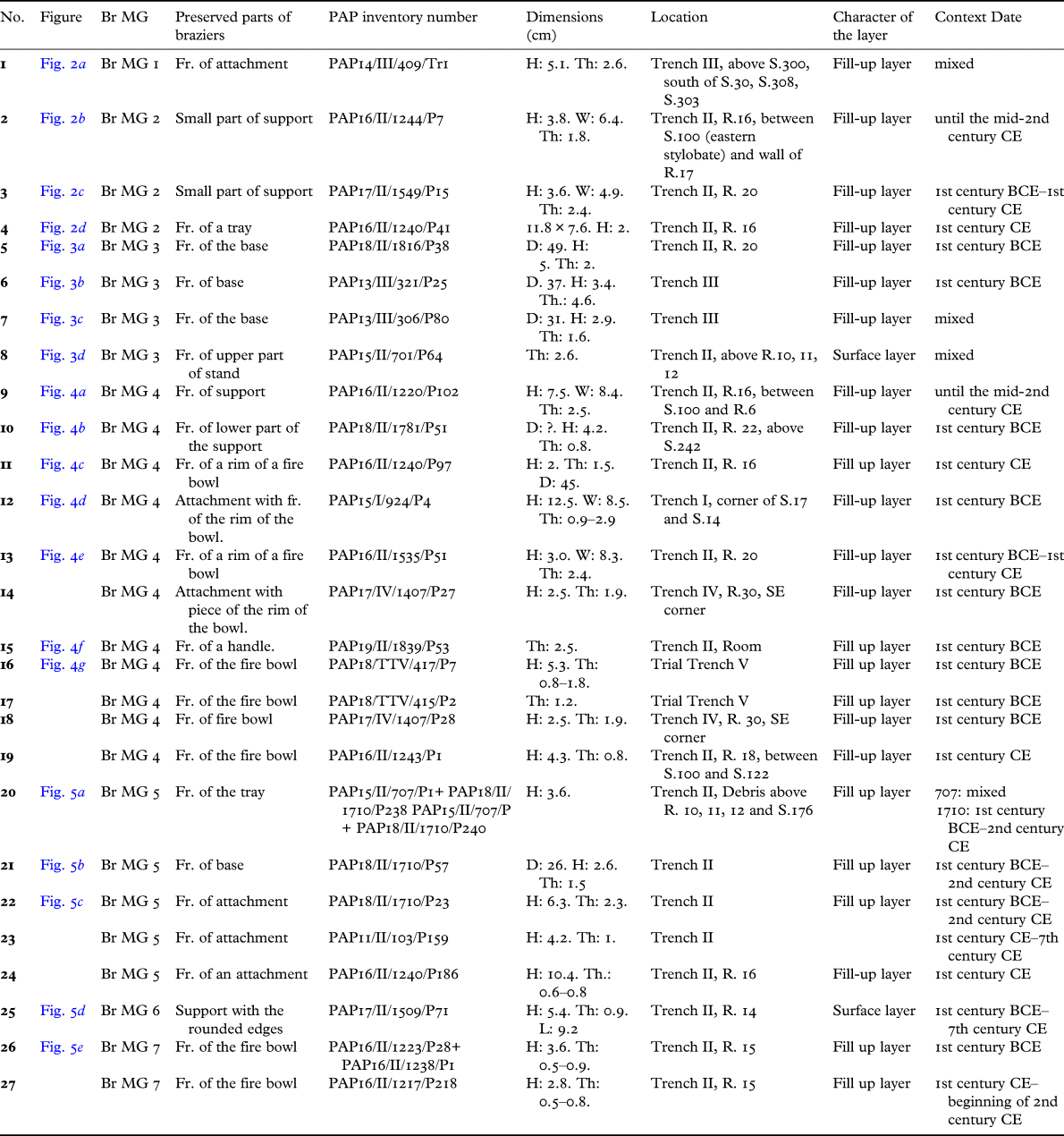

Table 1. The characteristics of the Br MGs discussed in the article.

Table 2. The catalogue of the braziers fragments from the Agora.

Br MG 1 – ‘Western Cypriot’ production(?)

The characteristics of the fabric of the Br MG 1 (Table 1) could match those observed in earlier studies concerning braziers from Nea Paphos. This fabric might correspond to Ware I of presumed Cypriot origin defined by Hayes (Reference Hayes1991, 75), which occurred from the Middle Hellenistic to the end of the LH period and was represented by more than a dozen examples. Another example of a brazier fragment that may be linked to this fabric was recorded in Maloutena in deposit D.5 (layer II), dated to the end of the second century BCE (Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka1995, 71, 125, no. 135). The ceramic mass of the brazier fragment from the Agora is comparable to Western Cypriot cooking pottery fabric dated to the LH period (Nocoń Reference Nocoń2020a, 300). However, due to the limited number of fragments of braziers found within the city, it is not certain if they were produced in Nea Paphos. Together, there are fewer than 20 fragments recorded so far (Table 3). No moulds have been found. Further laboratory analysis is required to solve this issue.

Table 3. Finds of braziers in the Nea Paphos area.

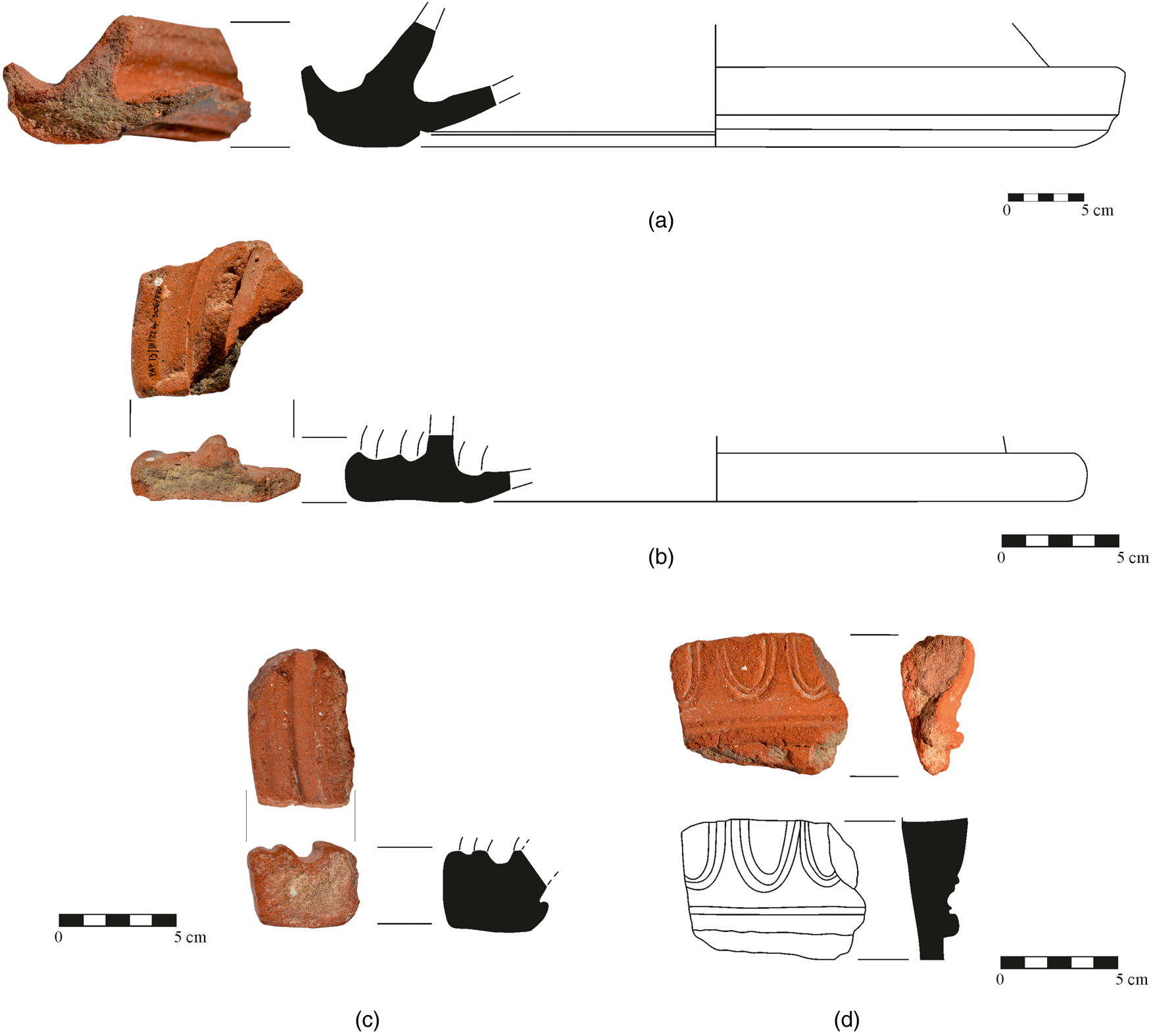

The fragment presented here (Table 2:1, Fig. 2a) is too poorly preserved to establish a type, and precise dating is problematic as well. It was found in a context of mixed character and contains part of a bearded mask; it is difficult to determine to which type it belonged: head with pilos, head with onkos, or head with ivy wreath (Conze Reference Conze1980, 120–4; Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 208). The fragment under consideration possesses a part of a face with large open mouth, covered by a long, twisted moustache and a long beard. Close resemblances to the shape of the beard and mouth can be found among the fragments from the House of Dionysos (Room ΓΞ, Well 17), of presumably local production and dated from the mid- to the third quarter of the first century BCE (Hayes Reference Hayes1991, 75, cat. no. 2, 171, cat. no. 9, pl. 17:2). Other good parallels are from Akko (Berlin and Stone Reference Berlin, Stone, Hartal, Syon, Stern and Tatcher2016, 168, fig. 9.14:1) and Dor (Rosenthal-Heginbottom Reference Rosenthal-Heginbottom and Stern1995, fig. 5.1:5), both dated to the middle of the second century BCE.

Fig. 2. Brazier Macroscopic Group 1 – Western Cyprus(?): (a) no. 1. Brazier Macroscopic Group 2 – Knidos?: (b) no. 2, (c) no. 3, (d) no. 4. Courtesy of Paphos Agora Project.

Br MG 2 – Knidos origin(?)

Br MG 2 (Table 1) was tentatively linked with the south Aegean region, with Knidos as the most probable place of manufacture (Şahin Reference Şahin2001, 129–30; Reference Şahin2003, 86). This fabric is not very frequently occurring in the studied assemblage and consists of only three examples, which were found in contexts dated to the LH and ER periods in Rooms 16 and 20 within Trench II. Two fragments of brazier attachments belonged to the brazier with a low stand. The first one (Table 2:2, Fig. 2b) is a fragment of the upper part of a support with square, slightly concave, edges and a thin horizontally projecting rim. In the field surrounded by the ridge there is an onkos with eight preserved locks where the four on top form a V-shape. The second (Table 2:3, Fig. 2c) belongs to the same type, but with four preserved locks on one side of the onkos. Its inner surface is blackened. These fragments belong to the Conze III type (Conze Reference Conze1890, 126–9) and represent the head with parted and curve hair type proposed by Şahin (Reference Şahin2001, 102–3, cat. nos Ha33, Ha37); they are dated to the second half of the second century BCE. They are also correlated with the Athenian Agora III.1.b type – Satyr with onkos distinguished by S. Rotroff (Reference Rotroff2006, 208). This type is widely distributed in many Mediterranean sites (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 208–9). An example is also known from Priene (Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 360, table 61:A454), dated to the second century BCE. No traces of inscription have been noted on the presented fragments. Further fragments of this group belong to a brazier with the horizontal tray (Table 2:4, Fig. 2d). A few are known from Priene dated to the third quarter of the second century BCE (Rumscheid Reference Rumscheid, Delemen, Çokay-Kepçe and Özdizbay2008, 1083); however, the largest collection of this type of brazier comes from Delos, where they are dated to the beginning of the first century BCE (Didelot Reference Didelot and Drougou2000, 143).

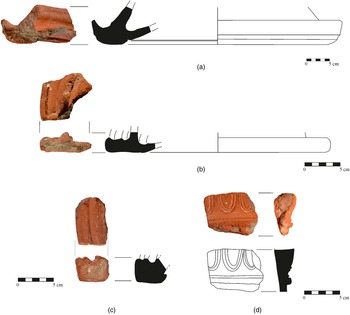

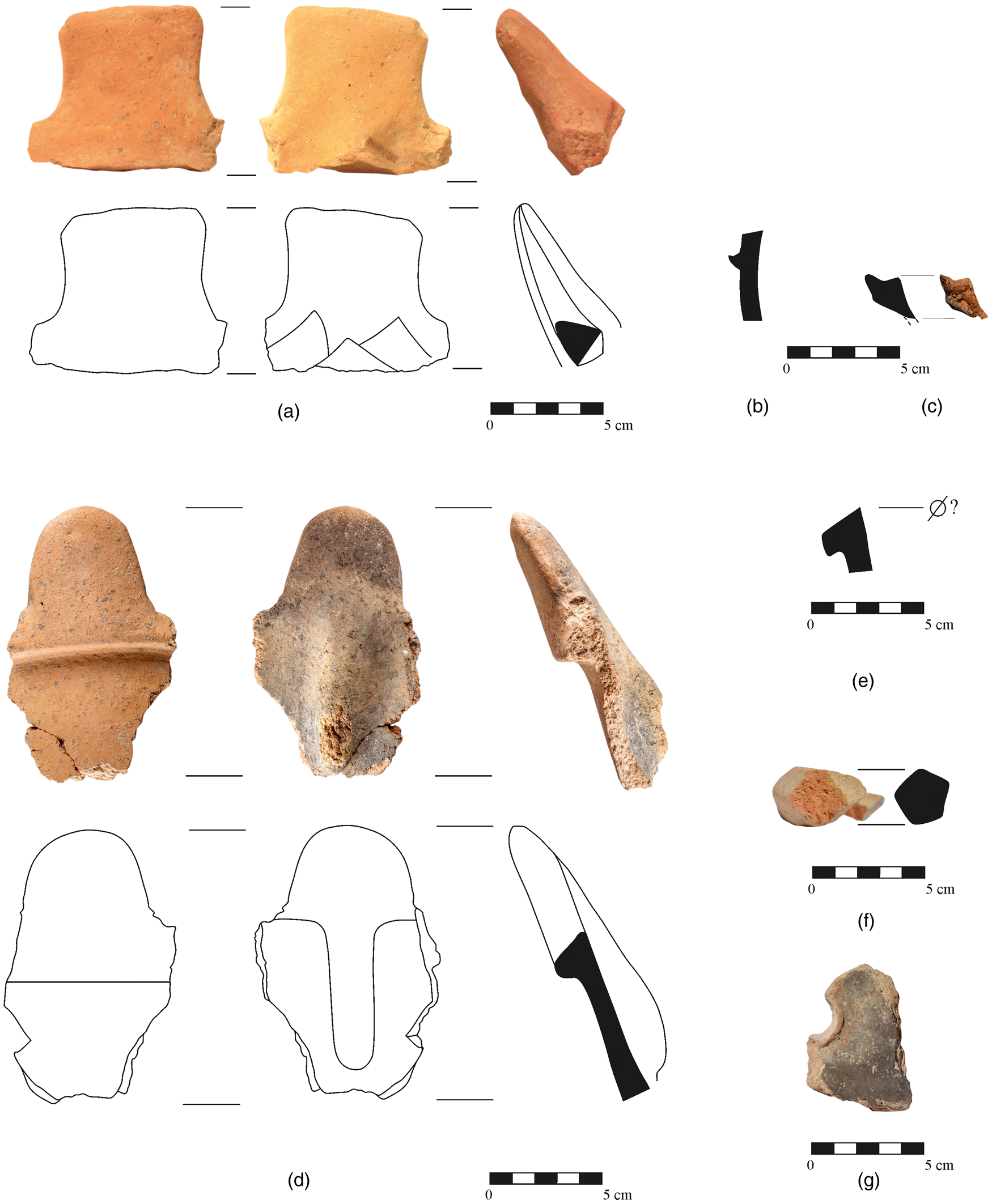

Br MG 3 – Asia Minor fabric 1

This fabric may be correlated with the Égéen type described by O. Didelot (Reference Didelot and Müller1997, 381) and Quartz Cooking fabric, identified on the basis of the finds from the Athenian Agora and probably produced in one of the centres located in the Aegean region (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 40). It is another minor fabric group found in the Agora in Nea Paphos, consisting of four pieces. A fragment of the base of a brazier (Table 2:5, Fig. 3a) comes from a well-stratified context dated to the first century BCE, and we can surmise from the diameter of its base that it probably belonged to a large brazier; however, this type of base appears earlier at many sites. The closest analogies can be found in Priene (Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 427, pl. 102:B363) and in the Athenian Agora (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, fig. 95:803), dated to around the first quarter of the second century BCE. Another type of base included in this group (Table 2:6, Fig. 3b), which possesses two deep grooves on the top, was also found in this context, dated to the LH period. It is nearly square-shaped in the cross-section and could be tentatively linked with one example found in Priene (Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 361, pl. 61:A459), its fabric interpreted as being of Aegean origin dated to the middle of the second century BCE (Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 100–1). A further fragment of the base in the assemblage probably belonged to a smaller brazier (Table 2:7, Fig. 3c), though with no direct analogies. This group is also represented by the fragment of an upper part of a stand, with an impressed ovolo stamp (Table 2:8, Fig. 3d) – a pattern frequently used on the braziers, with close parallels found in Samaria (Rahmani Reference Rahmani1984, 227, no. 11, pl. 30:9,11), Knidos (Şahin Reference Şahin2003, pl. 30:KF5), the Athenian Agora (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 322–3, pl. 86:812), Athens (Vogeikoff-Brogan Reference Vogeikoff-Brogan2000, 308, fig. 39), and Priene (Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 426, pl. 101:B358) with a chronology that spans the second and first century BCE. It seems that these fabrics emerged in the Agora in the LH period.

Fig. 3. Brazier Macroscopic Group 3: (a) no. 5; (b) no. 6; (c) no. 7; (d) no. 8. Courtesy of Paphos Agora Project.

Br MG 4 – Benghazi local fabric 1, Benghazi shell rich ware, or Cyrenaican marl clay fabric

The most characteristic feature of this fabric (Table 1:Br MG 4) are macrofossils on the surface visible to the naked eye, which allows for the fabric to be linked with Benghazi local fabric 1, named also as Benghazi shell rich ware established by J.A. Riley (Reference Riley and Lloyd1979a, 305; 1979b, 38) and recently named Cyrenaican marl clay fabric (Swift Reference Swift2018, 85–8). The place of production was attributed to ancient Berenike, located in Cyrenaica, on the basis of the common features of this fabric, such as its pale orange-brown colour and a large number of grey shells of the foraminiferal genus Heterostegina, typical for the geology of the Benghazi region (Riley Reference Riley1979b, 38; Krywonos et al. Reference Krywonos, Newton, Robinson and Riley1982, 64). This fabric was mainly used for the production of several series of cooking pots (Riley Reference Riley and Lloyd1979a, 305; Swift Reference Swift2018, 86), as well as amphorae (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 46–9) and frying pans, the shape of which was inspired by Phocean frying pans (Swift Reference Swift2018, 86). Braziers were produced there from the Hellenistic period until the third century CE (Riley Reference Riley and Lloyd1979a, 304).

This group is the most numerous and contains 11 fragments of braziers, of which four were found in contexts with a well-established chronology. The majority of fragments were found at the Agora in several rooms located in the central part of Trench II and one in the area of Trench I. All the presented fragments are blackened from the inside, which indicates use.

Benghazi brazier ‘Type A’

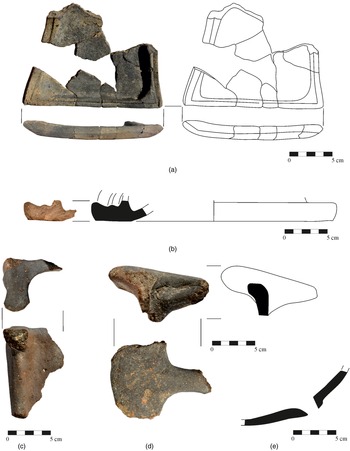

Several fragments can be linked to the Hellenistic Benghazi brazier ‘Type A’ (Riley Reference Riley and Lloyd1979a, 304–5, fig. 113:691). The earliest example from the studied assemblage is a fragment of a support with square and slightly concaved edges and a minor part of the high central groove – ‘nose’ like type – located on the internal surface (Table 2:9, Fig. 4a). A small part of the rim of the fire bowl has a triangular shape in the cross-section. This fragment was found in the area tentatively interpreted as an ‘Office of the Paphos Surgeon’ (Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka2016), in a context including thousands of fragments of tableware, cooking pottery, as well as amphorae, dated to the second century CE. The closest parallel (a fragment of an attachment) can be found in the House of Dionysos (Room ΓΛ), from the bottom of the deposit dated to the second quarter of the second century BCE (Hayes Reference Hayes1991, 76, cat. no. 18, fig. 26:18, pl. 18:4). The second parallel (fragment of a female mask) also comes from the House of Dionysos (Room AΛ), dated to the late second century BCE (Hayes Reference Hayes1991, 77, cat. no. 22, 140). The lower part of the support with a projecting horizontal groove on the external surface confirms that the influx of this type of braziers continued in the LH period (Table 2:10, Fig. 4b). It was excavated in Room 22 (Trench II) in a context that contains many fragments of cooking pottery and amphorae as well as fragments of rims of ESA form 15, form 19, and form 22. The further fragment is a rim and upper part of a fire bowl (Table 2:11, Fig. 4c), which was found in the context ranging from the LH to the ER periods, with most of the material dated to the Augustan period.

Fig. 4. Brazier Macroscopic Group 4: (a) no. 9; (b) no. 10; (c) no. 11; (d) no. 12; (e) no. 13; (f) no. 15; (g) no. 16. Courtesy of Paphos Agora Project.

Benghazi brazier ‘Type B’

Typical for the LH period, the Benghazi brazier ‘Type B’ (Riley Reference Riley and Lloyd1979a, 305, fig. 113:692) is represented by two fragments of attachments with an internal, central ‘nose type’ projection and with a fragment of the rim of the bowl (Table 2:12,14, Fig. 4d). Another fragment that belonged to this type is the rim of the fire bowl (Table 2:13, Fig. 4e). Fragments of this type of brazier usually occur in layers dated to the LH period, although they rarely appear in contexts that contained significant quantities of pottery dated to the Augustan period. A further parallel can be found in the House of Dionysos, from an upper deposit of Room ΓΞ dated to the Augustan period (Hayes Reference Hayes1991, 76, cat. nos 17, 18, fig. 26:17).

Other fragments

The fragment of a handle with pentagonal shape in the cross section is a very rare find (Table 2:15, Fig. 4f). It was discovered in the context dated to the LH period. In Greece, they occur much earlier, as indicated by examples from Corinth and Athens from the second century BCE (Edwards Reference Edwards1975, 119–20, pl. 61:647; Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 219, 333, cat. no. 814, pl. 84:814; Liston, Rotroff and Snyder Reference Liston, Rotroff and Snyder2018, 8, 85, cat. no. 69, fig. 77). In the studied assemblage, a few fragments belonging to the fire bowls with a part of a rounded perforation and often blackened by fire from the inside have been found (Table 2:16–19, Fig. 4g). They were most frequently found in contexts dated to the LH period and rarely to the ER.

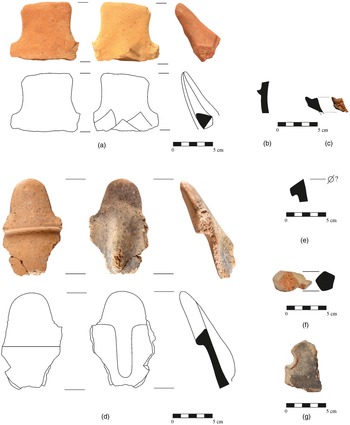

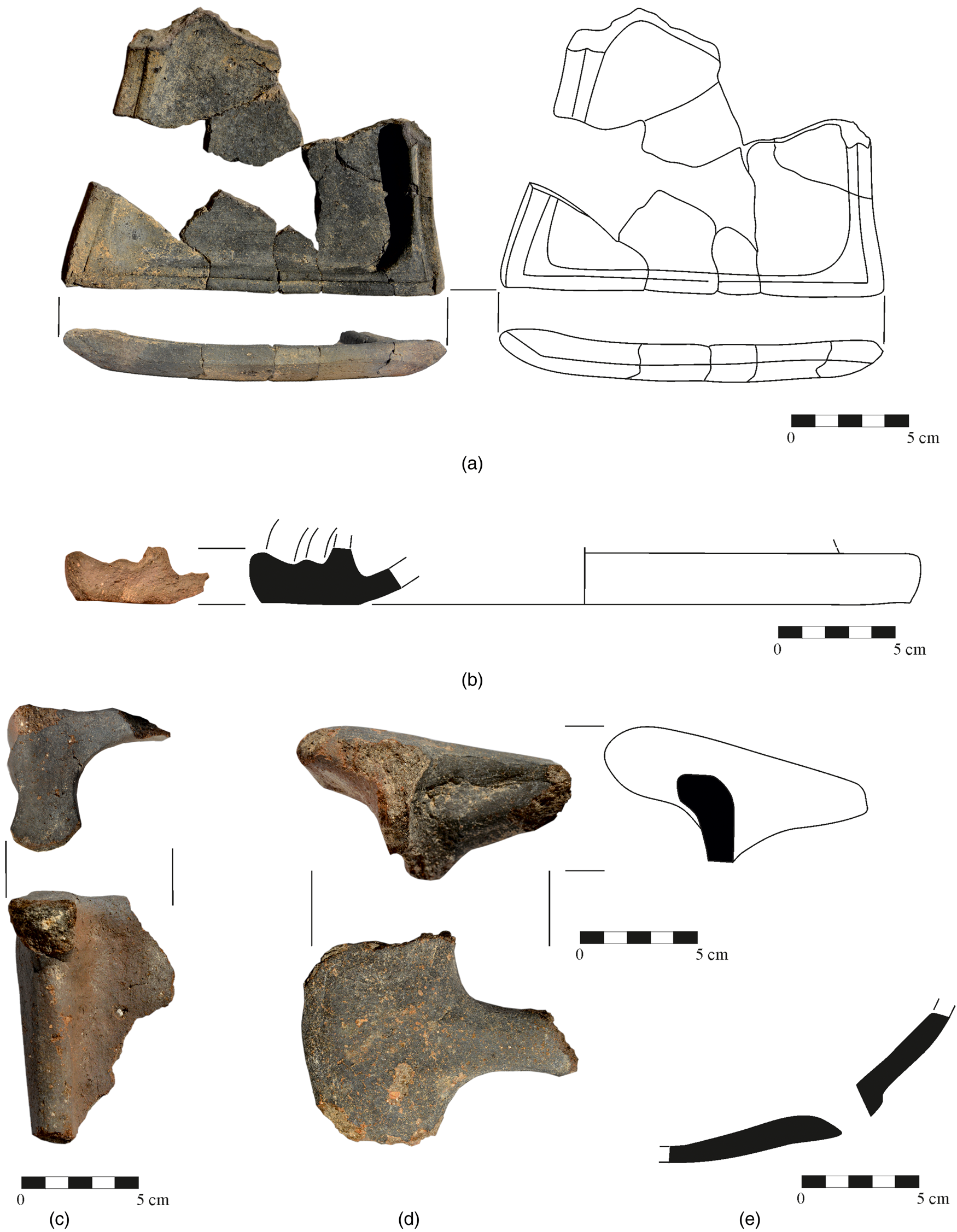

Br MG 5 – dark fabric with grey inclusions

This group is represented by fragments of probably two different types of braziers. The largest fragment is a part of the tray with a concave shape (Table 2:20, Fig. 5a). The pieces of tray show similarities to the ship type brazier used in the LH and ER periods (Leonard Reference Leonard1973, 25, no. 11; Galili and Rosen Reference Galili, Rosen and Tripani2015, 342, fig. 7; Doksanalti and Aslan Reference Doksanalti and Aslan2018, 665, fig. 4m). The fabric is also found in the fragment of the base with two deep grooves on the external surface (Table 2:21, Fig. 5b). Other parts belonged to the attachments of the large horseshoe-shaped fire bowl (Table 2:22–4, Fig. 5c). Those fragments may be linked to a low brazier on a stand with a tray. Two very close parallels come from the Bodrum Museum collection (Leonard Reference Leonard1973, 24, nos 7 and 8), dated to the Hellenistic period. The braziers of this type are less common in the studied assemblage than those mentioned above. The fragments under consideration were found in the context dated to the LH and ER periods; a few were found in the surface layer of mixed chronology in the area of Trench II. The source of this fabric is unknown.

Fig. 5. Brazier Macroscopic Group 5: (a) no. 20; (b) no. 21; (c) no. 22. Brazier Macroscopic Group 6: (d) no. 25. Brazier Macroscopic Group 7: (e) no. 26. Courtesy of Paphos Agora Project.

Br MG 6 – dark brown fabric with dark orange inclusions

Only one brazier fragment of this group (Table 1) has been identified amongst the finds from the Agora: a part of the plain support with rounded edges. The position of the support to the rim suggests that the support was inclined inwards (Table 2:25, Fig. 5d). A fragment of the rectangular rim is visible in the cross-section. Braziers with these plain supports are not common in the Eastern Mediterranean. Several are known from the Athenian Agora (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 221), Knidos (Şahin Reference Şahin2003, 50–1), and Caesarea Maritima (Gendelmann Reference Gendelmann2006, 33); however the provenance of the fabric is not specified. The closest analogies regarding the shape of the presented fragment can be found in the collection of braziers from the Athenian Agora, dated to the third century BCE onwards (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 219–20, cat. nos 830–1). Even so, the shape of the whole brazier is still unrecognised. It also cannot be ruled out that the fragment belongs to a ‘horseshoe’ cooking stand, which is often found on many sites and is dated to the second and early first centuries BCE (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 220). Dating based on the stratigraphy is problematic due to the mixed character of the context in which the fragment was found. Braziers with this type of support are rare in Nea Paphos, and the fragment in question must be regarded as the first of its kind.

Br MG 7 – dark brown fabric with transparent inclusions

Three small perforated fragments, with the diameter of the holes of approximately 1–2 cm (Table 2:26–7, Fig. 5e), possibly belong to the hemispherical bowls. They were found in Room 15 (Trench II) in a context dated to the LH period. Another fragment comes from the same room but from the context dated to the ER period. The provenience of the fragments classified in this group is problematic to determine, due to the damaged caused by burning, which makes it difficult to identify the clay macroscopically. Rotroff (Reference Rotroff2006, 217) argues that the way of manufacturing may suggest the place of origin, and thus the construction of the holes may suggest the Aegean tradition of manufacture.

DISCUSSION

So far, our analysis of braziers has described their provenance and their typological and chronological variability. Fragments within examined Br MGs represent the whole assemblage currently known from the Agora. Although the presented results are preliminary, they nevertheless allow for some conclusions to be drawn. For a better understanding of the role of braziers, it is necessary to harmonise the finds within a wider social and economic context.

The influx of braziers to Nea Paphos in archaeological and historical context

In the late third or early second century BCE, Nea Paphos became the capital of the island, which broadly affected the society and economy of the city and its vicinity (Młynarczyk Reference Młynarczyk1990). Due to its location along the main maritime route between many poleis of the Eastern Mediterranean, the city came to play a major role in the island's prosperity and cosmopolitanism. As previously noted, the earliest examples of braziers are dated to the Early Hellenistic period on the basis of evidence from the House of Dionysos (Hayes Reference Hayes1991, 75) supported by the finds from the Agora. The presented data indicates that braziers were imported from two main directions: from the places of production located in Asia Minor (Br MG 3, Br MG 5, Br Mg 6) and from Benghazi (Br MG 4). The emergence of braziers from the Aegean region by the end of the second century BCE is undoubtedly linked to the large number of imports (Lund Reference Lund2015; Papuci-Władyka and Miszk Reference Papuci-Władyka and Miszk2020, 516–19, table 2). The contrast between the number of brazier fragments and the very large number of imports, including many categories of tableware (Lund Reference Lund2015; Marzec and Kajzer Reference Marzec and Kajzer2020), amphorae (Dobosz Reference Dobosz2020), cooking pottery (Nocoń Reference Nocoń2020a; Reference Nocoń2020b), and lamps (Kajzer Reference Kajzer2020; Kajzer et al. Reference Kajzer, Marzec, Kiriatzi and Müller2021) dated to the Middle and LH periods, from several centres in Asia Minor, is very noticeable. Nevertheless, brazier groups imported from this direction are evidence of strengthened economic and cultural links with the Aegean region. A fragment from the Agora indicates the beginning of imports of braziers from Berenice in the second century BCE; however, these are very rare. With the beginning of the LH period, the economic relations of Nea Paphos on the supra-regional market intensified. The position of Nea Paphos was further boosted when it became an important centre of ceramic manufacture, as demonstrated by evidence such as the group of Colour Coated Ware (Marzec et al. Reference Marzec, Kiriatzi, Müller and Hein2019), lamps (Kajzer Reference Kajzer2020; Kajzer et al. Reference Kajzer, Marzec, Kiriatzi and Müller2021) and cooking pottery (Nocoń Reference Nocoń2020b; Marzec et al. Reference Marzec, Nocoń, Miziołek, Kiriatzi and Müllerin preparation; Nocoń and Marzec Reference Nocoń and Marzecin preparation). The local production of many categories of pottery undoubtedly affected economic conditions and trade. Therefore, further considerations about the production of braziers in Nea Paphos are very important (Br MG 1). Braziers from the Aegean region dominated in the Agora in the LH period. Several examples from the studied assemblage are dated to the second century BCE but were mostly found in the LH contexts. During this period, the number of fragments produced in Berenike increased. At the Agora, apart from the brazier fragments, a few other objects from Cyrenaica were found, however mostly in contexts dated to the ER period: a fragment of the upper part of a disk of a lamp (M. Kajzer, pers. comm.), a few coins dated to the Early Imperial period (Bodzek Reference Bodzek2020, 389), and amphorae (Dobosz Reference Dobosz2020, 344). A further major socio-economic and political change occurred after 58 BCE when Cyprus was annexed by the Romans (Młynarczyk Reference Młynarczyk1990), although only a few brazier fragments were attested in contexts dated to the Augustan period.

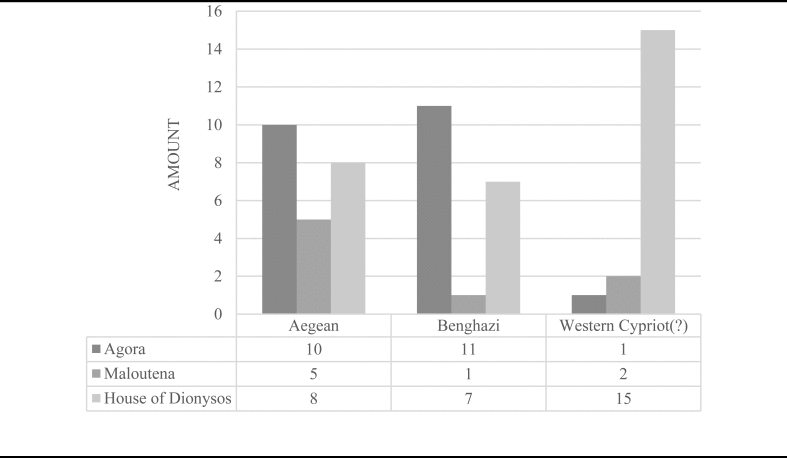

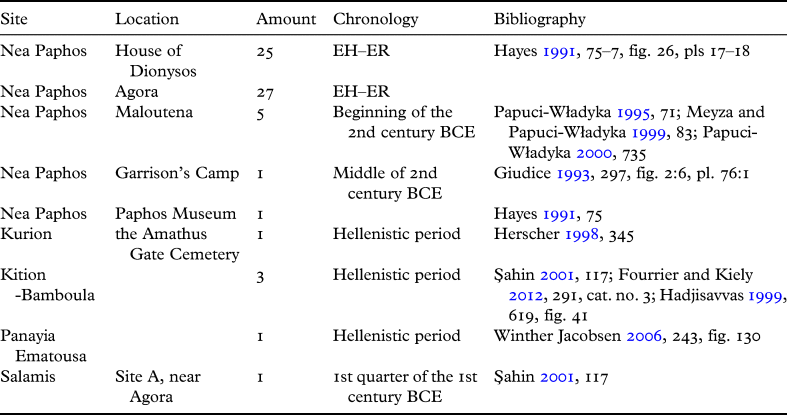

The proportion of different groups of braziers from the Agora confirms the trend of imports of this category of artefacts noted so far in the city (Table 3). The dominance of fragments of braziers of Aegean origin, the largest number of which were found in the Agora, confirms the general tendency of the distribution of braziers in the Eastern Mediterranean (Didelot Reference Didelot and Drougou2000; Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 200). However, it seems that finds from this direction are fairly evenly distributed within the city. The second most frequent group of brazier fragments was of Benghazi production. Besides the above-mentioned fragments from the House of Dionysos, a few examples of braziers of this fabric have also been uncovered during the Polish Excavations in Maloutena (E. Papuci-Władyka, pers. comm.). Among the rarest are braziers of presumed Cypriot origin, which predominate in the House of Dionysos. The beginning of the production of local imitations of braziers dates to the early second century BCE. A similar process occurred in Athens during the same period (Liston, Rotroff and Snyder Reference Liston, Rotroff and Snyder2018, 87).

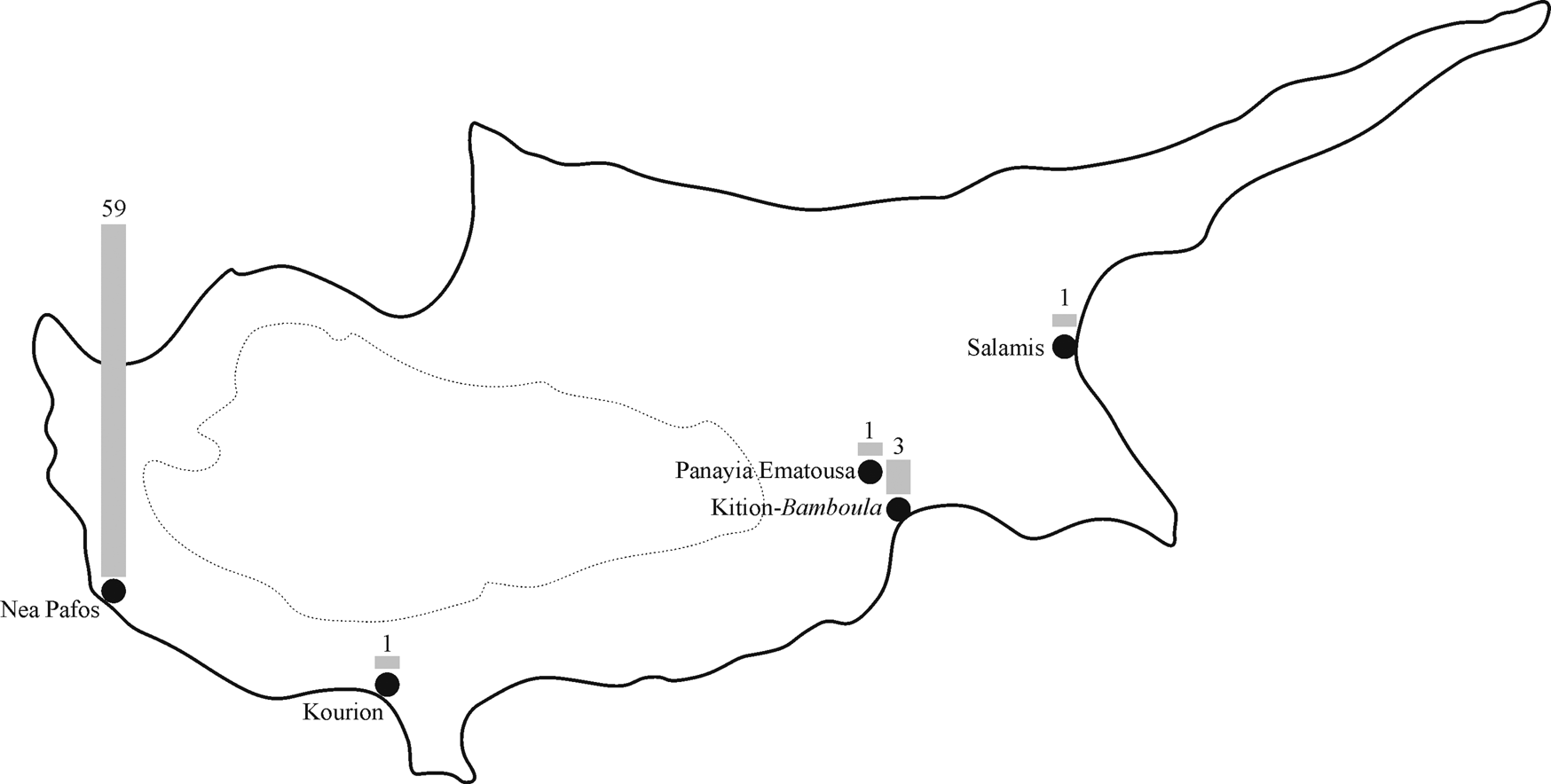

The archaeological evidence from many sites in the Mediterranean region indicates that braziers were mostly supplied to coastal communities living in cities located on major sailing routes (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 201; Fabbri Reference Fabbri and Peignard-Giros2019, 15). This trend is also confirmed in Cyprus (Fig. 6); however, as can be seen in Table 4, the proportions of the distribution of braziers on the island are very diverse. Apart from four cases, we know almost nothing about the Hellenistic braziers from other parts of the island. However, the clear regional trajectories are illustrated by the contrast between the number of finds from Nea Paphos and the finds from the other coastline poleis like Kition-Bamboula, Kourion, Salamis, and – additionally – a village located in the hinterland named Panayia Ematousa. These finds mostly include fragments of attachments of braziers with a high and low stand, represented by the most common type: bearded head with onkos or pilos. There is no available dating for the braziers from Benghazi from other sites on Cyprus, and it seems that braziers of this provenance only reached Nea Paphos. Braziers produced from this ceramic fabric were very rarely found in the Mediterranean, as in the case of the above-mentioned fragments from the Athenian Agora. Another example comes from Alexandria (Hayes and Harlaut Reference Hayes, Harlaut and Empereur2002, 115, fig. 72, pl. 2:3) and is dated to the first half of the second century BCE. An important point that emerges from the variation in the spatial distribution of braziers in Cyprus is that generally they were not as common as in other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Nevertheless, the finds from Nea Paphos provide support for J. Lund's (Reference Lund2015, 159) argument concerning the distribution of pottery in Cyprus during the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, designating Western Cyprus as the area with the most intense circulation of pottery. However, it is important to keep in mind that the region of Nea Paphos has been the subject of many more archaeological investigations than other parts of the island.

Fig. 6. Regional trajectories of distribution of Hellenistic braziers on Cyprus.

Table 4. The proportions of recorded braziers in Cyprus.

Braziers in Nea Paphos in the social context: cultural shift or short-lived fashion?

As mentioned above, braziers were used in many areas of the Mediterranean and were a manifestation of certain ideas connected to individual or group identities. Cyprus was located on the borders of strong economic and cultural networks (Lund Reference Lund2015), but the case of the supply of braziers to the island suggests relatively weak links between the producers and consumers. Contrarily, considering the size and importance of the city of Nea Paphos in the Hellenistic period, the large number of fragments of braziers for which there is evidence is not surprising. The distribution of portable braziers in Nea Paphos articulates the choices and social needs of the community of the city and could have taken place as a consequence of different factors. Still, the number of braziers, compared to other categories of import, is small. When dealing with such limited imports, it seems likely that they were not caused by a specific or sustained demand, but rather were derivative of regional interactions in the network of more sustainable economic connections. Braziers are generally rare finds at all sites and only found in large numbers where vast quantities of other ceramics were uncovered. This is probably due to their relative rarity, durability and probably long use-life. At this point, discussion will turn to the hypothetical functions of braziers in Nea Paphos.

The hypothesis that braziers may have been used as kitchen utensils is strengthened not only by the archaeological evidence (Didelot Reference Didelot and Drougou2000, 137–8), but also by archaeological experiments, which have indicated that braziers, which were compact in size, allowed for speedy food preparation under specific environmental conditions (Mosyak et al. Reference Mosyak, Galili, Daniel, Rozinsky, Rosen and Yossifon2017; Doksanalti and Aslan Reference Doksanalti and Aslan2018, 662–3). However, the context of the finds of braziers in the Agora does not directly indicate their use in the process of food preparation. Most of the analysed fragments were found in a number of rooms located within Trench II, which are tentatively connected with a commercial and/or artisan function (Miszk Reference Miszk2020, 153). Fragments of braziers have also been found in places with similar functions in Athens (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 201) and Tell Atrib (Południkiewicz Reference Południkiewicz, Jakubiak and Łajtar2020). It is also important to keep in mind that kitchen areas in Greek houses are hard to identify (Foxhall Reference Foxhall2007, 240), and no traces of kitchens dating back to the Hellenistic period have been found so far, neither in the Agora nor at the other sites within Nea Paphos. Nevertheless, such a place, interpreted tentatively as a kitchen, was discovered in Maloutena, dated to the Early Roman period (Więch Reference Więch2017a). The size of the attachments and the diameters of the bases suggests that most of the braziers found on the Agora appear to have been small in size. This may indicate that their reduced proportions required a smaller amount of fuel to cook, which would need to be constantly replenished. This may have caused less efficient heating and a slower process of cooking. As was noticed by Scheffer (Reference Scheffer2014, 180–1), a small number of braziers could be used by an equally small group of people. The analysis of cooking pottery from the Agora dated to the LH and ER periods suggests that the prevailing way in which food was prepared was by boiling and stewing, as indicated by the very large quantity of cooking pots and casseroles produced during these periods. Many of the fragments of these vessels are blackened by the fire or even burnt. The contrast between the very large number of many of types of cooking vessels, which had a production peak in the LH period, and a relatively small number of braziers leads to the conclusion that in Nea Paphos braziers may not have been used as a primary source of fire during the cooking process.Footnote 6 However, at other sites, also plain or simple cooking stands seem to have been used (Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 220–2).

The hypothesis of another function should also be considered. M. Şahin (Reference Şahin2003) has argued, by reference to the more frequent sanctuary finds and the decorations, that relief-decorated braziers with high stands and mould-made attachments were used in cultic contexts during sanctuary visits as well as at home. In many locations in Greece and Asia Minor, a large number of braziers and their fragments (mainly attachments) were found in sanctuaries or in their vicinity (Scheffer Reference Scheffer2014, 178). However, our comprehension of the role of braziers in the worship of the local deities in Nea Paphos is problematic, as there is no precise evidence linking them to this practice. Another possibility is that braziers were deployed as altars connected with the worship of Hephaistos, the patron of metalworkers (Conze Reference Conze1890). This hypothesis is linked to the interpretation of the function of the area of Trench IV on the Agora, where traces of a metal workshop were found with remains of the kiln as well as many fragments of casting moulds with preserved channels and fragments of slag (Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka2016). Due to the paucity of data, this hypothesis is offered tentatively, but given the strong metallurgical traditions found in Cyprus, it is not impossible. Braziers in the vicinity of the workshops were also found in Tell Atrib (Południkiewicz Reference Południkiewicz, Jakubiak and Łajtar2020, 93). Even if their original use was ritual or domestic, it is possible that they were recycled for use in workshops. Industrial use is suggested by an example from Naukratis, with traces of pine pitch which were found on it (Thomas Reference Thomas, Villing, Bergeron, Bourogiannis, Johnston, Leclère, Masson and Thomas2015, 4). The fact that very few braziers were found in Nea Paphos can also be associated with a very strong cult of local gods, especially in the Hellenistic period, not to mention the strongly anchored, continuous, and indigenous cult of Aphrodite. Nevertheless, it is likely that the various inhabitants of Nea Paphos who used the braziers in their daily rituals had their own personal understanding of and relationships with the deity.

Perhaps, therefore, this small collection of braziers may be interpreted as ‘exotica’ in the material culture of Hellenistic Nea Paphos. Nevertheless, they provide further evidence that the local consumers were connected to wider trends and fashions. Moreover, they are also an indication of the transfer of some practices, connected with collective habits of certain groups of people in the specific cultural context.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has examined the Hellenistic braziers uncovered by the excavations on the Agora in Nea Paphos. Analysis was undertaken through a combination of macroscopic analysis of the ceramic mass with typological comparanda and chronological studies. The studies delivered new evidence for seven Brazier Macroscopic Groups characterised by different features including fabric, types, and chronology. The second aim of this research was to better understand the emergence of braziers in Nea Paphos in a socio-economic context. The theoretical implications of these findings are yet to be finalised; however, the main developments covered in the discussion are important in furthering our understanding of the role of braziers in everyday life by offering different hypotheses regarding their use as utensils for cooking or their association with certain practices of a religious nature. These results make an important contribution to research concerning certain aspects of the material culture of the Hellenistic period and strengthen the idea of the circulation of pottery in the western part of Cyprus. However, more research on this topic needs to be undertaken to confirm or reject the evidence for the production of braziers in Nea Paphos.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was carried out as part of a MAESTRO 6 grant (no. 2014/14/A/HS 3/00283) led by Professor Ewdoksia Papuci-Władyka (Jagiellonian Univeristy in Kraków, Poland), the director of the Paphos Agora Project, and financed by the National Science Centre in Poland. I would like to express my sincere thanks to prof. E. Papuci-Władyka for permission to study the braziers from the Agora and the discussion concerning braziers from Maloutena. The photographs were provided by A. Oleksiak, M. Link-Lenczowski and the author. Drawings are by A. Jurkiewicz-Cora, and by the author.