Implications

We found effects of both age and medical treatment history on milking order, and these suggest that health disorders may have long-term measurable effects on the position of a cow in the milking order, even when the effect of age on milking order is accounted for. These findings could lead to a better understanding of factors influential on the milking order in dairy cows, and therefore might result in better management around the milking procedure with an understanding of the potential for medical treatments to influence behaviour around milking.

Introduction

Animal health issues have an economic and animal welfare influence on dairy production. The most common diseases seen in dairy cows are lameness and mastitis, and much is already known about the response of individual cows to clinical treatments for these conditions and the behaviour of sick animals. For example, it is known that the time spent lying down and the number of lying bouts increases when lame cows are compared with non-lame cows (Calderon and Cook, Reference Calderon and Cook2011; Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Green and Tadich2013). In cows with mastitis, sickness is associated with a reduced lying time, an increased number of steps taken (more walking, less lying), and an increased rate of kicking during milking (Fogsgaard et al., Reference Fogsgaard, Bennedsgaard and Herskin2015). However, it is unknown if sickness in general can have long-term influences on behaviour.

Animal health issues can also influence behaviour around the milking and in the milking parlour. It is a generally held perception that cows follow a specific milking order (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Barr and Wieckert1967; Rathore, Reference Rathore1982; Grasso et al., Reference Grasso, De Rosa, Napolitano, Di Francia and Bordi2007). Several factors can influence the milking order, with sickness being one influence. Cows suffering from lameness may alter their position in the milking order as a result of their slowed approach to the milking parlour (Main et al., Reference Main, Barker, Leach, Bell, Whay and Browne2010; Varlyakov et al., Reference Varlyakov, Penev, Mitev, Miteva, Uzunova and Gergovska2012). Cows suffering from mastitis have been shown to stay behind in the milking order (Polikarpus et al., Reference Polikarpus, Kaart, Mootse, De Rosa and Arney2015), perhaps as a result of general malaise or even potentially associated with reluctance to be milked due to udder discomfort. A factor in milking order alteration may be that cows are fearful of the increased intensity of inter animal interactions that can occur in this high animal density area, and therefore are reluctant to go into the milking parlour (Munksgaard et al., Reference Munksgaard, De Passille and Rushen1999).

While there is published work on the association between sickness behaviour and milking order, less is known about the relationship between longer term medical treatment history and milking order. The major focus of this study was to investigate whether the age and medical treatment history of each cow in the herd affected its milking order.

Material and methods

Animals and management

The study was carried out at Wyndhurst Farm (Langford, UK), a commercial dairy farm with 204 lactating Holstein-Friesian cows at the time of the study. The number of milking cows in the herd varied slightly across the observation period because cows moved in and out of the milking groups, depending on their time of calving. The cows were housed in a loose cubicle housing system with sand as the bedding material, and slightly more than one cubicle available per cow. Only the group of cows that produced more than 40 l of milk per day (high yield group) and cows that were <150 days into the lactation were studied, as this group was housed in a part of the building which allowed very good unobstructed access for filming, and sufficient daylight for clear filmed images to be made, and enabled a ‘manageable’ amount of video data to be collected and analysed.

A total of 110 cows were recorded as being present in the high yield milking group during the study period: however, six cows were recorded as being sick during the period of video observation, and because the study aimed to look at ‘long term’ rather than ‘acute’ effects of disease, were removed from the analysis. Four cows moved in, or out, of the group during the observation period for routine milking group management purposes, and were not included in the statistical analysis, so, in total, 100 cows remained throughout the entire observation period and were included in the statistical analysis. Cows were milked in a 12×2 herringbone milking parlour, equipped with DeLaval milking equipment and with automatic cluster removal. The cows were milked three times a day, at 0500, 1300 and 2030 h. The whole group was collected and waited to be milked in the waiting area, which was 6.0×23.3 m (139.8 m2) in area with a gently sloping concrete floor. Cows were persuaded to move forward towards the milking parlour by a backing gate, which used electrified hanging wires and noises (a beeper) to motivate the cows to walk into the milking parlour.

Data collection

Information about the milking order was collected for five consecutive afternoon milking sessions, which started at 1300 h every day. Cows were identified when entering the milking parlour by using the installed DeLaval MultiReader, which read the cow ID from a transponder as they entered the milking area and was used by the milking machine to record milk production for each cow. Cows were filmed by two cameras (GoPro HERO4 Silver, 2014) positioned at a height of 2 m and above the heads of the cows on the entrance gate of the milking parlour, overlooking the waiting area. The cows passed directly under the cameras as they entered the parlour, and were identified either from the DeLaval Multireader, or by the ear tag or freeze band numbers, or by comparison against a photographic ID chart which contained pictures of the head, back and both sides of each cow. Cows that joined or left the herd during the observation period as a result of management changes in the groups made by the farmer and sick cows were excluded from the analysis.

Information about the cows’ age and medical history was derived from data input by the farmer to the Interherd programme (NMR, 2011), which was used by the farm to record information about the cows, including: calving dates, milk production data, veterinary treatment and management events. Although we considered that the experience of the animal from early life could affect the milking order position of the animal throughout its life, we used health event data available in the record for each animal in Interherd from the start of the first lactation until the start of the study. As only very small numbers of records were available about health events in these cows before they entered the milking herd (from first lactation), the influence of health events before the first lactation on milking order position could not be examined. The number of sickness events was noted per cow as a cumulative measure of each animals’ health. Disease cases were detected by the farm staff, and, in liaison with the farm vet, a treatment programme was initiated. It was the start date and end date of these treatment programmes, which were used to identify ‘disease case incidences’ in the data.

If the same disease event was recorded to have occurred within 14 days after the first event, it was considered as one event (the same event). For example, a case of mastitis with multiple health entries and treatments on record, and stretching across up to 14 days duration, was considered as one health event. When the same health event happened, for instance mastitis, but was noted in the Interherd record to have been ‘resolved’ within those 14 days, the condition was recorded as two events. Events included in the health record and so included as ‘health events’ were mastitis, lameness, metritis, vulval discharge, milk fever, digestive disorders, downer cow (cow unable to stand), high cell count, ketosis and undiagnosed sickness (when the animal was sick, but a clear diagnosis was not made). For this group of cows, for some health events – the event count was ‘0’ – that is, some individuals did not have any recorded cases of, for example, vulval discharge. For this study, we chose to summate all health events to give a combined value for the ‘medical treatments’, our choice to combine health events being based on our hypothesis that cows with more generalised ‘treatment history’ could probably lose their milking order position as a result of a reduction in social behaviours. This hypothesis is based on the potential association between current health status and social behaviours previously described by Proudfoot et al. (Reference Proudfoot, Weary and von Keyserlink2012).

Statistical analysis

Collated data were analysed in SPSS 23 (IBM, 2016). The major focus of the analysis was to examine possible associations between previous medical treatments and age on milking order. Repeated measures ANOVA were used to examine whether age, and medical treatment history (sum of all sickness events per animal), significantly influenced the milking order. Kendall’s correlation coefficient was used to evaluate consistency of the milking orders and correlations in both tests were considered significant when P<0.05. The Kendall (1938) rank correlation coefficient evaluates the degree of similarity between two sets of ranks given the same set of objects. We selected Kendall coefficient to offer a statistical test able to examine milking order consistency, and to be sensitive even to a single disagreement, making it less likely to attribute significance to milking order similarities, and so to offer a ‘conservative’ test for the significance of milking order. To assess the association between cow ‘age’ and the ‘number of disease events’, we calculated the Pearson product-moment correlation between the factors ‘age’ and ‘total number of sickness events’.

Results

In total, 65 cows had a medical treatment history (i.e. had a record of a medical treatment) with a mean number of treatments of 2.44 (±3.37 SD), ranging from 1 treatment to a maximum of 16 health events. Mastitis, lameness and vulval discharge were the most common events recorded, with respectively 49, 65 and 65 cases in total. Mean age of the cows was 4.05 (±1.67 SD) years old, with a minimum and maximum age of, respectively, 1.9 and 9.0 years old. The association between cow ‘age’ and the ‘number of disease events’ was explored using Pearson product-moment correlation between the factors ‘age’ and ‘total number of sickness events’, with a correlation of r=0.781 (df=98), indicating a high degree of association between the age of the animal, and the number of disease ‘events’ experienced by the animal.

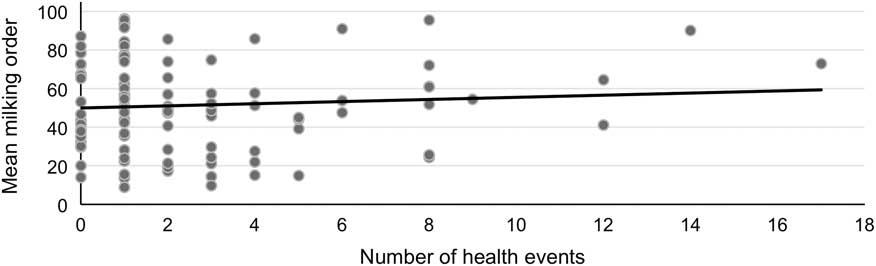

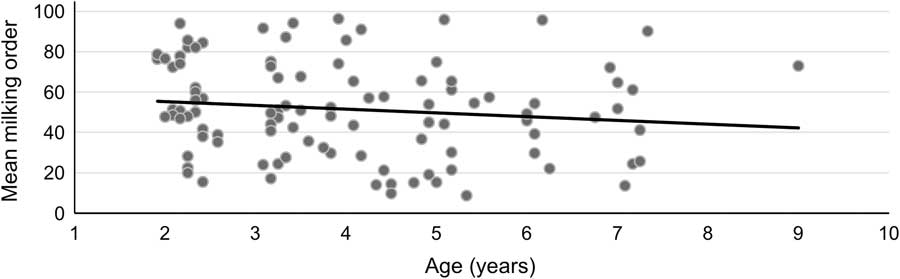

A significant positive correlation was found between medical treatment history and milking order rank (F=5.632; P<0.05; df=1), indicating that cows with a higher medical treatment history tended to enter the milking parlour later than cows with a lower medical treatment history (Figure 1). A significant negative correlation was found between age and milking order rank (F=4.965; P<0.05; df=1), indicating that older cows tended to enter the milking parlour earlier than younger cows (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Relationship between the number of health events and mean milking order rank for 100 dairy cows.

Figure 2 Relationship between age (years) and mean milking order rank for 100 dairy cows.

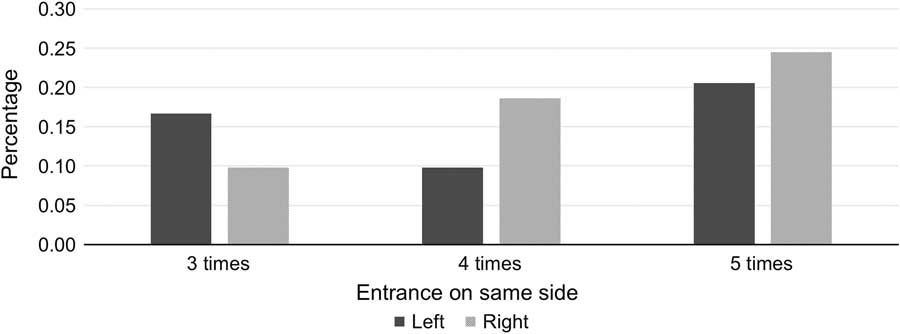

The collected milking orders (n=5) were tested for consistency using Kendall’s correlation coefficient (Table 1), and a statistically consistent milking order was found (P<0.01), indicating that overall cows remained consistent in their milking order within the period of the study. Side preference was also examined. 45 cows entered the milking parlour five times on the same side, 28 cows entered the milking parlour four times on the same side and 27 cows entered three times on one side and two times on the opposite side (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Preferred side of entrance to the milking parlour during the observation period (5 days) in 100 dairy cows.

Table 1 Consistency of milking orders for 100 cows between the observation days

Numbers represent Kendall’s correlation coefficient.

*Values differ significantly at P<0.01.

Discussion

Two significant influences on milking order were found in this study. First, it was found that older cows were more likely to enter the milking parlour early when compared with younger animals. This finding is supported by the findings of Berry and McCarthy (Reference Berry and McCarthy2012), who reported a correlation between cow parity and milking order. A low correlation between age and milking order was also found in goats (Margetínová et al., Reference Margetínová, Brouček, Apolen and Mihina2003). Cows may be fearful of the high density of interactions that occur in the crowded waiting area, and may be reluctant to go into the milking parlour (Munksgaard et al., Reference Munksgaard, De Passille and Rushen1999). Younger cows, and especially freshly calved heifers who are entering the milking group for the first time, have less experience with walking into the milking parlour than older cows and could therefore be more fearful than older cows. The somewhat complex interaction between age, medical treatment history and milking order presented in this study indicates that health disorders may have measurable long-term effects on the position of a cow in the milking order. It should be noted that the interherd data used in this study did not give any information on the location where treatments were given, and so it was not possible to assess the effect of ‘treatment in the milking parlour’. It is recognised that ‘location of treatment’ information would be of value, and could be collected over a long period preceding any future behavioural study.

Another question addressed in this study was whether milking order was consistent. The day to day milking order appeared to be very weakly but significantly consistent during the observation period, indicating that cows tended to follow a repeatable order when walking into the milking parlour. This consistency of milking order has also been found in other studies in dairy cattle (Grasso et al., Reference Grasso, De Rosa, Napolitano, Di Francia and Bordi2007), buffalo cows (Polikarpus et al., Reference Polikarpus, Grasso, Pacelli, Napolitano and De Rosa2014) and sheep (Villagrá et al., Reference Villagrá, Balasch, Peris, Torres and Fernández2007). Polikarpus et al. (Reference Polikarpus, Kaart, Mootse, De Rosa and Arney2015) found that milking order in dairy cows was consistent within and across days, but seemed to be more variable within milking sessions. The milking parlour used in this study had a right and a left side and, in addition to consistency in milking order, cows have shown a side preference, as described by Grasso et al. (Reference Grasso, De Rosa, Napolitano, Di Francia and Bordi2007).

An association was seen between medical treatment history and the individual cows’ place in the milking order. Cows with a higher medical treatment history tended to enter the milking parlour later than cows with a lower medical treatment history during the observations. A possible explanation for this finding is that cows with a higher medical treatment history may have had negative experiences in the milking parlour, for example as a result of udder discomfort in case of mastitis, and therefore stay behind in the milking order. In addition, lame cows may alter their position in the milking order as a result of a slowed gait, and may not be able, or perhaps even unwilling, to return to their previous position in the milking order after recovery. No previous work can be found about this association, as this study is the first to compare the total medical treatment history of cows to milking order instead of assessing the milking order at the time of the disease occurring. Further research on this subject is recommended to increase the sample size in future studies to determine whether this finding is common across more farms and dairy production systems. The potential commercial, or management benefits of the findings of this preliminary study could be that, by linking measures of behaviour (perhaps collected automatically using cameras as part of precision livestock developments) it might be possible to use jointly analysed behavioural and health history information, to inform decisions on management, to better understand long-term effects of medical treatments, and to inform decisions on retention of cows.

Conclusions

Somewhat contradictory effects of both age and medical treatment history on milking order were found, and these suggest that health disorders may have long-term measurable effects on the position of a cow in the milking order, even when the effect of age on milking order is accounted for. In addition, milking order in dairy cows appears to be consistent and cows show a side preference when entering the milking parlour. It is possible that either (a) changes in cow social behaviour, perhaps collected automatically, could be used as metrics of the impact of disease and medical treatments on cows, or that (b) the influence of medical treatment rates on the social behaviour of cows could be better understood, and mitigated against. The current study was a preliminary study in the area of ‘long term effects of disease and treatments’, an area that has not been heavily studied yet. This was a pilot study to explore the practicalities of the methodology, and it is possible that analysis of bigger data sets, if possible containing more information on the ‘detail’ of how treatments were given, collected over longer periods, and from larger herd size samples, would allow improved understanding of temporal effects on milking order position linked to disease experience. This information could potentially be of use by producers to inform decisions on treatment, management, and retention of cows within their milking herds.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank William Streatfield, David Tisdall and David Hichens for their help on the farm and with the Interherd programme and farm data and Osama Almalik for the support with the statistical analyses.