INTRODUCTION

Around 1600, bifolia belonging to an Old English glossed psalter were used in a bookbinder’s workshop as material to support the construction of various early modern books. From the late 1960s onwards, fragments of this glossed psalter have been recovered in various archives across Europe. In 1968, Klaus Dietz called attention to two vertically-cut parchment strips in the collection of fragments in Pembroke College, Cambridge, that were evidently once used as endleaf guards of a book that still remains unidentified.Footnote 1 In 1972, René Derolez reported on another fragment from the same manuscript: a single strip of parchment cut horizontally from a bifolium which had been removed from one of the bindings of an unidentified book in the municipal library of Haarlem, the Netherlands.Footnote 2 Twenty-five years later, Herbert Pilch discovered more of the psalter (two-thirds of one folio) in the collection of membra disiecta of the Schlossmuseum of Sondershausen, Germany.Footnote 3 Pilch’s edition and analysis were greatly improved upon by Helmut Gneuss, who published a new and definitive edition of the ‘Sondershausen Fragment’ in the following year and demonstrated that this had once been part of the same manuscript as the Cambridge and Haarlem fragments.Footnote 4 In 2023, Monika Opalińska, Paulina Pludra-Żuk and Ewa Chlebus presented two further endleaf guards of the Cambridge type (cut vertically) that belonged to the same glossed psalter. Fortunately, these endleaf guards were still attached to the binding of their host volume, a grammar of Hebrew published in 1600, now in the C. Norwid Library in Elbląg, Poland.Footnote 5

The present article calls attention to the discovery of a relatively large number of further fragments that were once part of the same Old English glossed psalter: eight endleaf guards of the Haarlem type, cut horizontally from various bifolia, and thirteen parchment strips that were used as spine linings.Footnote 6 These twenty-one fragments were found in a four-volume set of an undated edition of the Thesaurus Graecae linguae by Henri Estienne that once belonged to the municipal library of Alkmaar, the Netherlands, but is now part of the collection of the Regional Archive, Alkmaar.Footnote 7 Watermarks of the paper used for the flyleaves and pastedowns suggests that these books were bound around the year 1600.Footnote 8 An overview with measurements of the individual fragments is provided below, per volume of the set:

Vol. 1. Front endleaf guard (334 × 55 mm) containing Pss. CXVIII.136–8, 144–5; CXXVII.2–3; CXXVIII.1–3. Back endleaf guard (339 × 53 mm) containing Pss. CXVIII.131–2, 138–40; CXXVI.2–3; CXXVII.3–4. A single parchment strip used as a spine lining (44 × 100 mm) containing parts of Ps. LIV.3–5, 9–11.

Vol. 2. Front endleaf guard (336 × 55 mm), cut from the lower margin of a bifolium, which shows traces of the bottom of capital M of Mandasti (Ps. CXVIII.138) and the tail of the ę in tuę (Ps. CXXVII.3). Back endleaf guard (336 × 49 mm) containing Pss. CXVIII.133–4, 140–2; CXXVI.4–5; CXXVII.5–6. Six parchment strips used as spine linings (49 × 108 mm; 24 × 111 mm; 22 × 112 mm [no text]; 22 × 110 mm; 25 × 110 mm; 44 × 108 mm [no text]), containing Ps. XLIII.8–11, 14–17.

Vol. 3. Front endleaf guard (339 × 50 mm) containing Pss. LXXXV.2–3, 9–10, 14–15; LXXXVI.2–3. Back endleaf guard (337 × 48 mm) containing Pss. LXXXV.1–2, 7–9, 13–14, 17–LXXXVI.2. Two parchment spine linings (45 × 131 mm; 40 × 128 mm) containing part of Pss. XLII.5–XLIII.2, 4–6; two further parchment spine linings (125 × 29 mm; 126 × 24 mm) containing part of Ps. XLIII.11–12, 17–18; and two parchment spine linings that contain no text (126 × 22 mm; 124 × 29 mm).

Vol. 4. Front endleaf guard (339 × 57 mm) containing Pss. CXVIII.134–6, 142–4; CXXVI.5–CXXVII.1, 6–CXXVIII.1. Back endleaf guard (330 × 49 mm) containing Pss. CXVIII.175; CXIX.5; CXX.6–7; CXXI.6. The six parchment strips used as spine linings in this volume are from a different manuscript, written in a script of the late twelfth century, featuring passages from the Decretum Gratiani.

The fragments have since been detached from the bindings and it has been possible to reconstruct that they belonged to nine individual folios; images of these reconstructed folios are included in this article as Plates I–XVIII. In the present article, these Alkmaar fragments are first introduced in the context of the other pieces of the ‘N-Psalter’ in Cambridge, Haarlem, Sondershausen and Elbląg. Next, the relationship between the Old English glosses in these fragments and the thirteen other extant Old English glossed psalters is outlined.Footnote 9 A subsequent discussion of the language of the Old English glosses of the Alkmaar fragments is then followed by an attempt to uncover the provenance of the fragments and the N-Psalter as a whole. The article concludes with an annotated edition of the fragments, as well as Appendices with variant readings of the Old English and Latin texts.Footnote 10

Plate I. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A1r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III spine linings).

Plate II. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A1v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III spine linings).

Plate III. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A2r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, II, III spine linings).

Plate IV. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A2v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, II, III spine linings).

Plate V. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A3r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I spine lining).

Plate VI. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A3v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I spine lining).

Plate VII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A4r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III endleaf guards).

Plate VIII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A4v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III endleaf guards).

Plate IX. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A5r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III endleaf guards).

Plate X. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A5v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, III endleaf guards).

Plate XI. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A6r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I, II, IV endleaf guards).

Plate XII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A6v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I, II, IV endleaf guards).

Plate XIII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A7r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, IV endleaf guard).

Plate XIV. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A7v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, IV endleaf guard).

Plate XV. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A8r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, IV endleaf guard).

Plate XVI. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A8v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, IV endleaf guard).

Plate XVII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A9r (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I, II, IV endleaf guards).

Plate XVIII. Alkmaar fragments, fol. *N-A9v (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 135 A 9, I, II, IV endleaf guards).

THE ALKMAAR FRAGMENTS AND THE OTHER PARTS OF THE N-PSALTER

Once a full psalter with a continuous Old English gloss, the N-Psalter currently survives only in fragments. With the newly found Alkmaar fragments included, the complete or partial Old English glosses of a little under nine hundred Latin words have surfaced:

N-C = Cambridge, Pembroke College, 312C, nos. 1 and 2. Pss. LXXIII.16–21, 22–LXXIV.31; LXXVII.31–37, 37–43 (complete or partial OE glosses of 76 Latin words)

N-H = Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, Oude Boekerij, 188 F 53. Pss. CXIX.4–5; CXX.4–6; CXXI.4–5; CXXII.3 (complete or partial OE glosses of 65 Latin words)

N-S = Sondershausen, Schlossmuseum, Lat. liturg. IX 1.Footnote 11 Pss. VI.9–11; VII.1–9 (complete or partial OE glosses of 107 Latin words)

N-E = Elbląg, C. Norwid Library, SD.XVI.1480. Pss. CXIII.16–20, 22–26; CXIV.1 (complete or partial OE glosses of 70 Latin words)

N-A = Alkmaar, Regionaal Archief, 135 A 9. Pss. XLII.5; XLIII.1–2, 4–6, 8–12, 14–18; LIV.3–5, 9–11; LXXXV.1–3, 7–10, 13–15, 17; LXXXVI.1–3; CXVIII.131–45, 175; CXIX.5; CXX.6–7; CXXI.6; CXXVI.2–5; CXXVII.1–6; CXXVIII.1–3 (complete or partial OE glosses of 565 Latin words)

The claim that these fragments all derive from the same manuscript is based on a number of shared features. Each of those features is briefly described below, with reference to examples from the Alkmaar fragments (N-A).

First, all fragments share the same script for the Latin and Old English texts. Gneuss identified the script of the Latin text as an Anglo-Caroline Style IV minuscule with distinctive ra-ligatures, which suggests that the manuscript was made around the year 1050.Footnote 12 The Latin text of N-A has the same script and also includes ra-ligatures in contra (Ps. XLIII.16), exprobrantis (Ps. XLIII.17), erant (Ps. LIV.4), opera (Ps. LXXXV.8), coram (Ps. LXXXV.9), miserator (Ps. LXXXV.15), attraxi (Ps. CXVIII.131), desiderabam (Ps. CXVIII.131) and israhel (Ps. CXXVIII.1). The scribe did not use the ra-ligature consistently; N-A features a number of ra-sequences without the ligature: sperantem (Ps. LXXXV.2), adhorabunt (Ps. LXXXV.9) and requiram (Ps. CXVIII.145). This same combination of distinctive ra-ligatures and normal ra-sequences is found in the Elbląg fragments (N-E) – the Sondershausen fragment (N-S) only has ra-ligatures, while these ligatures are absent from both the Cambridge (N-C) and Haarlem (N-H) fragments.Footnote 13 In all extant fragments, the Old English gloss is written, probably by the same hand, in a smaller English vernacular minuscule, while the rubrics are written in uncial script.Footnote 14

The mise-en-page of the text of N-A is also similar to that of the other N-Psalter fragments. A full bifolium, reconstructed on the basis of five endleaf guards of N-A (see Fig. 1), reveals a writing frame of c. 210 × 140 mm, ruled for seventeen lines of Latin text (c. 12.5 mm per line; the drypoint ruling is at the headline and baseline of the Latin text). The folio-size can be estimated to be about c. 300 × 180–90 mm. This spacious presentation of the Psalter text is unusual compared to other Old English glossed psalters and may suggest that the N-Psalter was intended for annotation.Footnote 15

Figure 1. Reconstructed bifolium of N-A, showing a distribution of seventeen Latin lines per folio. For images of these fragments, see Plates XI–XII; XVII–XVIII.

This manner of ruling and the number of lines per folio corresponds neatly to N-S, which, having been cut vertically at folio length, is the only other N-Psalter fragment that contains the exact number of lines of Latin text each folio would have had. Another feature of textual presentation that each of the N-fragments share is the presence of verse initials (c. 9–11 mm high; c. 7–9 mm wide) in the alternating colours red, green and blue, which are located to the left of the main text block.Footnote 16 Psalm initials, in the same colours, take up a vertical space of three lines of Latin text and are found in N-C, N-S and N-A.

A further distinctive feature of the N-Psalter fragments, according to Gneuss, is a specific kind of punctus versus ;· at the end of verse lines, located at the right-hand edge of the writing frame, found in N-C, N-H, N-S and N-A.Footnote 17 Concerning this particular form of punctus versus, Gneuss claims that this ‘form [is] not frequently found elsewhere, if at all’.Footnote 18 However, this kind of punctus versus with one extra dot appears to be more common and the feature may not be as distinctive as has been assumed. Similar forms were used by, e.g., the tenth-century scribe identified as ‘Hand 4’ in the Parker Chronicle, as well as the eleventh-century scribe who added an Old English charm in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 190, p. 130.Footnote 19 Perhaps more significantly, a similar three-point punctus versus ;· at the end of verse lines is found in one other contemporary Old English glossed psalter: the Arundel Psalter (J), with which the N-Psalter has a small number of unique readings in common.Footnote 20

Further similarities between N-A and the other N-Psalter fragments include the version of the Latin Psalter text and its tituli. Like the other N-fragments, N-A is a Psalter Gallicanum with some Romanum readings, e.g., the Romanum et non egredieris deus in uirtutibus nostris (Ps. XLIII.10; also in ABCDEFHJK) rather than Gallicanum et non egredieris in uirtutibus nostris (found in G and I).Footnote 21 Furthermore, the rubrics, or tituli, in N-A appear to derive from the same source as those in the other fragments of the N-Psalter. For the rubrics of N-C, N-S and N-E, Opalińska et al. have identified the possible source as Pseudo-Jerome’s Breviarium in Psalmos. Footnote 22 Four complete rubrics in N-A also show similarities to the Breviarium (see Table 1).Footnote 23

Table 1: Rubrics in N-A compared to Breviarium in Psalmos

One further indication that N-A once belonged to the same psalter as the other N-fragments is the presence in both N-C and N-A of musical annotation in a later hand. Across the initial opening of Psalm LXXIII in N-C, a later hand has added the antiphon ‘In israheh (sic) magnum nomen eius’, accompanied by Anglo-Norman neums.Footnote 24 N-A features a similar addition by a later hand in the right-hand margin next to the opening of Psalm XLIII: ‘Eructavit cor meum verbum bonum’ with musical notation.Footnote 25

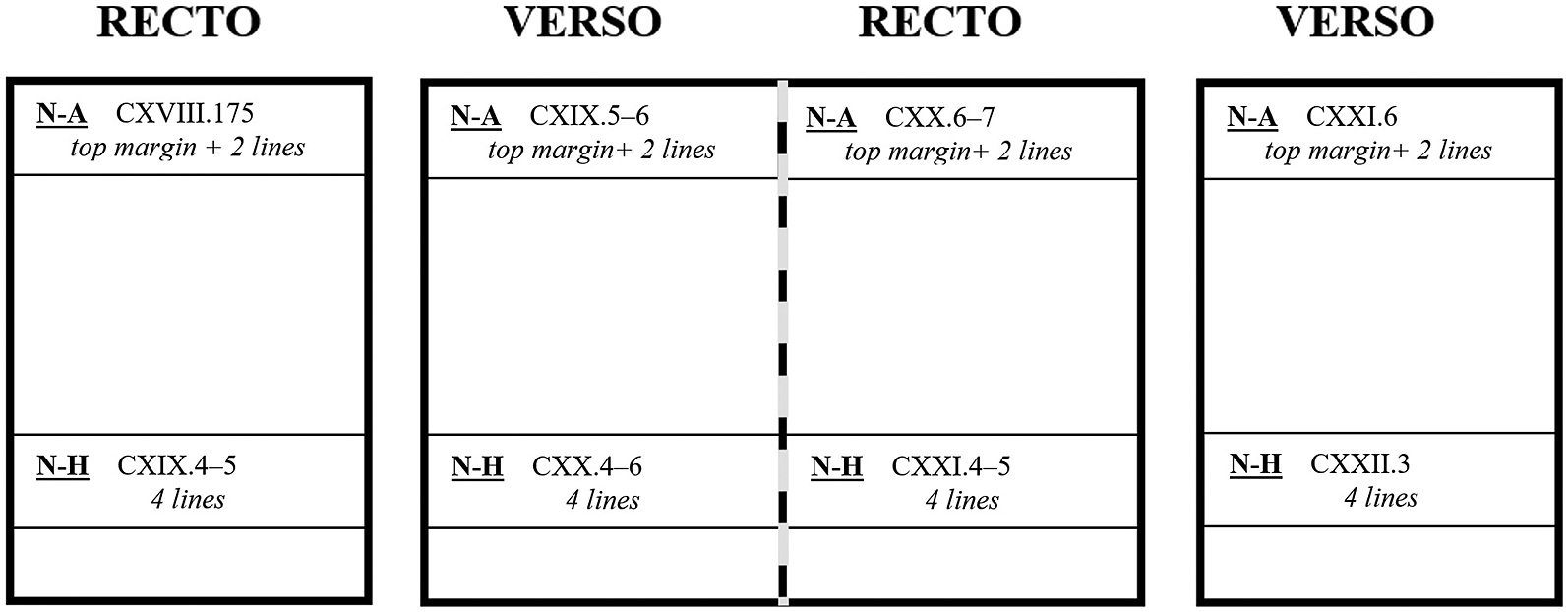

The claim that N-A belonged to the same manuscript as the other N-fragments can be further substantiated by the fact that one of the endleaf guards of N-A must have been cut from the same bifolium as N-H (see Fig. 2). Cut horizontally from the lower end of a bifolium, N-H contains the last four lines of each page and provides the text of Pss. CXIX.4–5, CXX.4–6, CXXI.4–5 and CXXII.3. One of the endleaf guards of N-A was cut from the top of the same bifolium and contains the top margin and the first two lines of each page, with the text of Pss. CXVIII.175, CXIX.5–6; CXX.6–7 and CXXI.6. In other words, in three places where the text of N-H breaks off, the text of N-A continues: Heu mihi, quia incolatus meus prolongatus est habitavi | cum habitantibus cedar (Ps. CXIX.5); Per diem sol non uret te, neque luna | per noctem (Ps. CXX.6); and sedes super domum David. | Rogate quae ad pacem sunt ierusalem (Ps. CXXI.5–6). The bifolium reconstructed in Fig. 2 would have been in the middle of a quire, given the fact that the text runs on from the first to second leaf. Moreover, this bifolium would have been part of the same quire as the bifolium reconstructed in Fig. 1 (where the left leaf covers Ps. CXVIII.131–45 and the right leaf Pss. CXXVI.2–CXXVIII.3). It is possible to estimate that this quire consisted of at least two further bifolia, covering the text of Pss. CXVIII.146–174 and CXXII.4–CXXVI.1.Footnote 26 This finding indicates that the quires of the N-Psalter were made up of at least four bifolia (eight leaves), which was a standard size of a quire in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, although quires of five or six bifolia also occur.Footnote 27

Figure 2. Reconstruction of a bifolium from which both N-H and one of the endleaf guards of N-A were cut. For images of these N-A fragments, see Plates XIII–XVI.

Given all of the shared features described above, there can be no doubt that the fragments now in Alkmaar once belonged to the same mid-eleventh-century manuscript as the fragments in Cambridge, Haarlem, Sondershausen and Elbląg. When it was still intact, that ‘N-Psalter’ would have covered around 200 to 220 folios, each ruled for seventeen lines of Latin text.Footnote 28 The Latin text was supplied with a continuous Old English gloss, probably by the same scribe, while a later hand provided the opening versicles of a number of psalms with musical notation.

TEXTUAL AFFILIATIONS OF THE OLD ENGLISH GLOSS

In his overview of the extant psalters from Anglo-Saxon England,Footnote 29 Philip Pulsiano notes how the relationship between the fourteen Old English glossed psalters is ‘under lively discussion’.Footnote 30 One of the complicating factors, as observed by Celia and Kenneth Sisam, is the fact that there must have been hundreds of Old English glossed psalters in the tenth and eleventh centuries, which makes drawing direct connections between the ones that still survive today unlikely and, thus far, impossible.Footnote 31 Rather than direct connections, scholars typically distinguish between three main Old English glossing traditions for the Psalms: the A-tradition, the D-tradition and the I-tradition.Footnote 32 The Old English glosses to individual psalters are generally ascribed to one of these traditions, but they can also show the influence of multiple traditions and will usually feature some idiosyncratic glosses. Deviations from the main traditions that are shared between two or more psalters have been used to establish more fine-grained hypothetical archetypes, but establishing a convincing stemma of the Old English psalter glosses has thus far proved very difficult.Footnote 33

Prior analyses of the N-fragments have shown that the Old English gloss of the N-Psalter belongs to the D-tradition, with close links to F and G. On account of a number of uniquely shared readings between N-C and F, Dietz argued for F as being closest to N,Footnote 34 while Derolez observed a number of instances where N-H did not correspond to F but followed G (as well as D and J), arguing in favour of G as the ‘nearest relative’.Footnote 35 Next, Gneuss, comparing the readings of N-S with the D-type psalters DFGJK, concluded that ‘neither F nor G can account for all readings’ and that ‘[i]f Ns had only one exemplar, this must have been remarkably close to D’.Footnote 36 Lastly, Opalińska et al. argued that most of the Old English glosses in N-E ‘are equivalent to those used in psalters D and F, and to a slightly lesser extent, also to those in G and H’. They further note that, given a number of significant lexical discrepancies, it is impossible that any of these psalters would have been the direct exemplar of N.Footnote 37

A comparison between the Old English glosses in N-A and those found in the other extant Old English glossed psalters largely confirms the picture painted above. N-A is clearly close to F and G,Footnote 38 but neither can ultimately be called the closest relative to N-A. The first two tables of selected variant readings in Appendix A list multiple instances where N-A differs from F and, instead, follows G as well as other psalters (especially D, H and J); the following two tables in Appendix A provide an overview of occasions where N-A differs from G in favour of a gloss that is found in F and other psalters (especially D, H and J). These correspondences and differences may be found on the levels of lexis, morphology and spelling. Gneuss’s assumption that the N-Psalter’s exemplar may have been very close to D is borne out by the last table in Appendix A, which lists glosses that differ from both F and G but typically follow D. A number of these Old English glosses are uniquely shared between D and N-A, including the gloss ‘comun’ for uenerunt (Ps. XLIII.18), the double gloss ‘swindan ł essian’ for tabescere (Ps. CXVIII.139), and ‘bebodu þina’ for mandata tua (Ps. CXVIII.131, 134, 143). Even more revealing of the closeness of N to D is N-A’s inclusion of a single Latin interpretative gloss ‘celestis hierusalem’ for sion (Ps. LXXXVI.2), which is also only found in D.Footnote 39

While the N-Psalter’s relationship to D, F, G and H had already been touched upon in prior scholarship, the collations in Appendix A show that N also shares a number of readings with J. Commonalities between J and N-A include the gloss ‘horn’ for cornu (Ps. XLIII.6) and similar double glosses for exprobrantis (Ps. XLIII.17) and excussorum (Ps. CXXVI.4).Footnote 40 A further similarity is the gloss ‘wanhafa’ for inops, ‘poor person’ (Ps. LXXXV.1), which is only found in N-A, F and J, in the context of this Psalm verse and nowhere else in the extant Old English corpus. More remarkably, a clear error in N-A is also found in J: for in conspectu suo (Ps. LXXXV.14), N-A glosses ‘on gesihðe þine’, apparently misinterpreting suo as Latin tuo; J has a similar gloss (‘on gesihðe þinre’), but here the Latin text has been altered to match the Old English gloss: in conspectu tuo. Footnote 41 In other words, along with F, G and H, J needs to be added to the D-type psalters that show some notable similarities to N.Footnote 42

N-A also shows a number of idiosyncratic glosses that are not found elsewhere; these have been collected in Appendix B. These unique readings mostly concern dialectal, spelling and morphological variants as well as a number of double glosses and errors, as discussed in the next section.

THE LANGUAGE OF THE OLD ENGLISH GLOSS

The language of the Old English glosses in the Alkmaar fragments is typical for (late) West Saxon and features, e.g., palatal diphthongisation (e.g., ‘ceaster’ for ciuitas, Ps. LXXXVI.3), breaking of æ before l plus consonant (e.g., ‘ealle’ for omnes, Ps. CXXVII.1) and absence of Anglian smoothing (e.g., ‘beseoh’ for aspice, Ps. CXVIII.132). Occasional non-West Saxon and archaic forms were probably copied from the D-type exemplar.Footnote 43 For instance, the scribe’s use of the archaic form ‘comun’ rather than comon (for uenerunt, Ps. XLIII.18) is exclusively shared with D and presumably has its origins in the exemplar – elsewhere the expected ending -on is used for the plural past indicative forms.Footnote 44 The same goes for the older form ‘self’ (for ipse, Ps. XLIII.5) in N-A and D, which is found as ‘sylf’ in the more consistently late West Saxon F and G.Footnote 45 The form ‘neoðeran’ (for inferiori, Ps. LXXXV.13) shows non-West-Saxon back mutation for more usual late West Saxon niðeran; the form in N-A is possibly derived from the D-type exemplar and shared with DFGK.Footnote 46 Not all of N-A’s non-West-Saxon forms are also found in D, however. For instance, N-A uniquely glosses sagittę (Ps. CXXVI.4) with ‘strela’, rather than expected late West Saxon stræla (found in DFGI). The non-West Saxon form ‘aflemendra’ (for excussorum, Ps. CXXVI.4), is shared only with G; the other glossed psalters provide different lexical glosses here, with the exception of the West-Saxon form of this word in J (‘aflimendra’).Footnote 47 On the whole, non-West Saxon forms are rare and the language in these glosses is generally typical of a late eleventh-century user of the West-Saxon variety of Old English.

In terms of morphology, the scribe’s use of possessive personal pronouns shows occasional reductions. For instance, the expected masculine accusative singular þinne and dative þinum are reduced to þine in: ‘on namann þine’ (for in nomine tuo, Ps. XLIII.9); ‘fac [ ] þine’ (for gedo seruum tuum, Ps. LXXXV.2; reduction shared with G); ‘hi wuldorfulliað naman þine’ (glorificabunt nomen tuum, Ps. LXXXV.9) and ‘ofer þeow þine’ (for super seruum tuum, Ps. CXVIII.135).Footnote 48 On one occasion, the expected feminine genitive singular form minre is reduced to mine, in ‘gescyndnis ansyne mine’ (for confusio faciei meę, Ps. XLIII.16).Footnote 49 The incorrect use of þine rather than þin for the feminine nominative singular in ‘æ þine’ (for lex tua, Ps. CXVIII.142) is an indication that -e may be this scribe’s default option for inflectional endings in the singular.Footnote 50 For the possessive pronouns modifying plural nouns, the scribe typically used -a endings, a feature shared only with D. However, the scribe is not entirely consistent, again opting elsewhere for -e: ‘bebodu þina’ (for mandata tua, Ps. CXVIII.131, 134, 143); ‘rihtwisnessa þina’ (for iustificationes tuas, Ps. CXVIII.136, 141); ‘fynd mine’ (for inimici mei, Ps. CXVIII.139); and ‘rihtwisnessa ðine’ (for iustificationes tuas, Ps. CXVIII.145). The reduction of the inflectional endings on the possessive pronouns is not an unexpected feature of late Old English.

Lexically, the Old English gloss of N-A is close to D, F, G, H and J (as discussed above) and does not stand out for its radically distinctive lexical choices. It does contain five instances of double glosses, marked by the abbreviation for Latin vel ‘or’,Footnote 51 that are of interest:

The first of these is unique to N-A (most of the D-type glosses have a form of styring ‘moving’) and provides the otherwise unattested word ‘gewændunga’,Footnote 52 derived from wendan ‘to turn’. This second gloss may reflect a possible alternative interpretation of the context of the phrase in this Psalm as referring to the turning of heads by the Gentiles, rather than the shaking of heads.Footnote 53 The second double gloss, which also occurs in I (‘aswarnung ł scamu’), was in all likelihood intended to provide a more common alternative for the rare aswarnung, which is only found in some Old English glossed psalters (N-A, D, F, H and I) and only in the context of this Psalm verse.Footnote 54 A similar motivation may underlie the double gloss for exprobrantis (‘hispendes ł odwitendes’; cf. ‘hispendra ł edwites’ in J): both interpretamenta are equivalent in meaning and they are mainly used in psalter glosses, but forms of the verb edwitan/ætwitan/oðwitan are more widely attested outside psalter glosses than forms of hyspan. The addition of ‘odwitendes’ in N-A may therefore be another instance of a more common alternative being supplied as a second gloss. Interestingly, the first gloss is a D-type gloss (‘hyspendes’ DEF; ‘hyspendest’ H; ‘hysspende’ K), while the second gloss seems to derive from another psalter gloss tradition (‘eðwetendes’ A; ‘edwitendes’ BG; ‘edwityndes’ C) – perhaps, therefore, the glossator had access to multiple glossed psalters. The double gloss for tabescere ‘to waste away, be consumed’ is also found in D (‘swindan ł essian’) and J (‘essian ł swindan’). Here, the first gloss swindan is also rare and only found in Old English glossed psalters, but the same seems to apply (to an even greater extent) for the provided alternative essian. According to the DOE, the verb essian, not attested outside these psalter glosses, may have been ‘derived from the adjective ȳþe “desolate, waste” which would give an infinitive *ȳþsian “to make weak”’; alternatively, it is an ‘error for otherwise unattested *lessian (cf. MED lessen “to become less”) … with initial l mistakenly copied as ł’.Footnote 55 If the latter interpretation is true, this double gloss is another instance of a rare and outdated word (swindan) being replaced with a more current alternative. The last double gloss appears to be prompted by the fact that the Latin word excussorum can be interpreted as the genitive plural form of both excussor ‘accuser’ and excussus ‘one who is cast out’.Footnote 56 The first interpramentum ‘worhborena’ is the genitive plural of the rare word wrohtbora ‘accuser, monster (lit.: blame-bearer)’ (as in the D-gloss ‘wrohtborena’), an Old English rendering of excussor,Footnote 57 while the second gloss ‘aflemendra’ is a possible translation of Latin excussorum ‘of the outcasts’.Footnote 58 N-A’s use of double glosses to provide more current alternatives for outdated words or additional translations for polysemous or ambiguous Latin words is in line with how double glosses were used by other Anglo-Saxon glossators.Footnote 59

Lastly, the Old English gloss also shows occasional errors. Some of these may be the result of misreading the exemplar. For instance, the glosses ‘lifiendum’ for diligentibus (Ps. CXXI.6) and ‘geambredon’ for fabricauerunt (Ps. CXXVIII.3) appear to be misreadings of lufiendum (as in D) and getimbredon (as in F). In the gloss ‘manegum’ for Latin uirtutibus (Ps. XLIII.10) the scribe switched around the n and g of magenum which was presumably in the exemplar (D has ‘mægenum’). Another error concerns the misinterpretation of the Latin preposition in as a negative prefix, which is found in the incomplete gloss for in testamento (Ps. XLIII.18): ‘uncyþnyss[ ]’. On one occasion, the scribe provided an uninflected form of Old English drihten to render a Latin genitive domini: ‘yrfe drihten’ (for hereditas domini, Ps. CXXVI.3); Opalińska et al. note the presence of similarly uninflected forms of drihten for dative forms in the various N-Psalter fragments and attribute this feature to incorrectly expanded abbreviations that must have been part of the exemplar.Footnote 60 Other erroneously uninflected forms among the N-A glosses include ‘in folc’ (for in populis, Ps. XLIII.15) and ‘ongeansprecende’ (for obloquentis, Ps. XLIII.17). These and other remarkable features of the scribe’s copying practice have been flagged in the annotated edition of the N-A fragments below.

PROVENANCE OF THE FRAGMENTS AND THE N-PSALTER

Until the discovery of the N-E fragments in Elbląg, little could be said about the provenance of the N-Psalter fragments; they were all apparently used to support the construction of early modern books, but no information was available about their host volumes. The fact that the N-E fragments were still attached to a book’s binding changed this situation dramatically, as Opalińska et al. have shown. The book in question, Casper Waser’s Archetypus grammaticæ Hebrææ (Basel: Conrad Waldkirch, 1600), was printed in the year 1600 and has a stamped supralibros that shows it belonged to Samuel Meienreis who died only four years later, in 1604.Footnote 61 Therefore, the binder of the book will have used the fragments of the N-Psalter somewhere between 1600 and 1604.

Meienreis’s biography and the binding technique used for his Hebrew grammar allows for pinpointing an even narrower chronological range as well as a possible location of the binder. Meienreis, born in 1572 in Elbląg (olim Elbing), was an affluent gentleman from Poland, who read theology at the University of Leiden, where he lived between December 1600 and April 1602.Footnote 62 There, Meienreis attended the lectures of Francis Junius the Elder (1545–1602), under whose supervision he defended his thesis on the Old and New Covenant on 19 January 1602.Footnote 63 Significantly, Junius, who had been professor of Theology at Leiden since 1592, had also been teaching Hebrew there between 1597 and 1601;Footnote 64 it is possible, therefore, that Meienreis bought his Hebrew grammar in Leiden, while he was studying with Junius.Footnote 65 Opalińska et al. point out that the binding of Meienreis’s Hebrew grammar shows features that are characteristic of both French and Dutch bindings of the period; they suggest the possibility of the book either having been bound in two separate stages (first in France, then in the Netherlands), entirely in France or by a bookbinder working in the Netherlands who was familiar with French binding techniques.Footnote 66 The last option points towards Leiden as a place where Meienreis’s book may have been bound. By the year 1600, Leiden was home to more than forty booksellers and bookbinders, including people like Louis Elzevir (1540–1617), who had gained experience as a bookbinder in Liège and Douay before setting up shop in Leiden in the 1580s (where he worked as a seller and printer of books, as well as a beadle and bookbinder for the University).Footnote 67 Thus, there is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that Meienreis bought his Hebrew grammar during his studies in Leiden and had it bound locally, somewhere between December 1600 and April 1602. At any rate, Meienreis is unlikely to have bought his book later than May 1602, when his deteriorating health forced him to leave Leiden and return home to Elbląg, where he would die two years later, at the age of 32.

The bindings of the host volumes of the N-A fragments show similarities to the book in Elbląg and also attest to a binder working with fragments of the N-Psalter around the year 1600. The N-A fragments were applied as support material for the bindings of each of the four folio-volumes of Henri Estienne’s Thesaurus Graecae linguae (n.d. [after 1572], sine loco), now in the Regional Archive in Alkmaar (135 A 9).Footnote 68 Like Meienreis’s Hebrew grammar, each of the four volumes had a laced-case parchment binding; these cases with their parchment covers, with V-notched turn-ins with overlapped corners, are now no longer attached to the book blocks. Each book block has five double sewing supports with herring-bone sewing. The endbands show sewing with alternating green and brown threads, with tiedowns. The parchment endleaf guards were sewn separately. The watermarks in the paper used as pastedowns and flyleaves suggest that these books were bound around the year 1600.Footnote 69 Each of the four volumes also show traces of two chain clips, as this four-volume set was once chained up in the municipal library of Alkmaar.Footnote 70

Another four-volume set that belonged to the same library in Alkmaar, with very similar bindings to the N-A set, features indications that the books were all bound in the Netherlands. This set (Alkmaar, Regional Archive, 136 E 4) constitutes the edition by Conrad Gessner of Galen’s works: Cl. Galeni Pergameni opera omnia (Basel: Froben, 1561–2). The bindings of these volumes (with the exception of volume 3 which has been refitted with a modern binding) have the exact same features as the N-A set, described above. The watermarks in the paper used for the pastedowns and flyleaves differ from the N-A set, although these also indicate that the book was bound around the same time.Footnote 71 In addition, like the N-E book, the volumes have sprinkled red edges. There are two further indications that the binder responsible for the N-A set was also responsible for this set of Galen books. First of all, the first volume of the Galen set has endleaf guards of the same late-twelfth-century manuscript of the Decretum Gratiani, of which strips were used as spine linings in volume 4 of the N-A set.Footnote 72 Second, since the parchment covered cases are detached from the book blocks in both sets, it is possible to see that the same hand who wrote the letters ‘F’ and ‘E’ on the insides of the pastedowns of volumes 2 and 3 of the N-A set, also wrote ‘H’, ‘J’ and ‘G’ on the pastedowns of volumes 1, 2 and 4 of the Galen set. Further annotations, in different ink, on the insides of the pastedowns of volumes 2 and 4 of the Galen set locate the binder in the Netherlands, since they are Dutch binding instructions to adjust the size of the binding: ‘Dese canten groot / grooter te maken | als de anderen / gvon[?] op de snede’ (vol. 2) [make this side big, bigger than the other … on the edge] and ‘Dese canten groter te maken als de ander’ (vol. 4) [make this side bigger than the other]. Given the fact that these instructions were clearly intended for the binder of the book (since they would no longer be legible once the endpapers had been pasted down), it is reasonable to assume that the binding workshop, which used the N-Psalter in the N-A set and the twelfth-century manuscript of the Decretum Gratiani in both volume 4 of the N-A set and volume 1 of the Galen set, was located in the Netherlands.Footnote 73

The fact that both sets in the Alkmaar archive, both bound around the year 1600, once belonged to the municipal library of Alkmaar provides a link with Leiden as a location where the books were bought (and possibly bound). According to the city records, the local city government of Alkmaar had sent Cornelis Hillenius and Adriaen Hendricxz Rabbi to Leiden in order to buy books for the municipal library at the auction of Daniel van der Meulen’s voluminous book collection.Footnote 74 This auction, supervised by Louis Elzevir, took place in Leiden on 4 June, 1601.Footnote 75 The Alkmaar patrons spent more than 400 guilders and returned to Alkmaar with a total of 27 books from the auction, with an additional 32 books (23 bound; 9 unbound) bought from various Leiden booksellers. The two four-volume sets are not listed in the book sale catalogue of the 1601 auction of Van der Meulen’s library, but they can be identified with titles in the records of the 1601 book-buying expedition.Footnote 76 The four-volume set of the Thesaurus Graeca linguae (containing the N-A fragments) was bought, bound, for the price of 23 guilders and 10 stivers; Gesner’s edition of Galen’s work was bought, bound, for the price of 24 guilders. The fact that these books were already bound when the Alkmaar patrons bought them in Leiden in 1601 is another reason for assuming Leiden as the location of the binder who used pieces of the N-Psalter.

The books in Alkmaar that contain the N-A fragments offer clues to unravel one more piece of the provenance puzzle of the N-Psalter: the missing host volume of the Haarlem fragment N-H. Regarding the host volume of N-H, Derolez notes:

The membra disiecta in the Haarlem collection must have been removed from the bindings of the books still in the Haarlem library, but the date and the circumstances of the operation have not been recorded. Neither has it proved possible so far to identify the volume from whose binding the Psalter fragment was reprieved. To be sure the number ‘168 B 4’, written in pencil on both sides of the fragment, is that of a volume actually in the library; but there can be no doubt that the strip was not removed from its binding.Footnote 77

Derolez’s claim that the book with the shelfmark 168 B 4 cannot possibly be the host volume of N-H is left unsubstantiated and needs to be revisited in the light of the discovery of the N-A fragments in the Thesaurus Graeca linguae books. As it turns out, the binding of the Haarlem book, a copy of Eusebius, De euangelica praeparatione libri XV (Paris: Robertus Stephanus, 1544) in Greek,Footnote 78 shares a number of features with the books in Alkmaar: it is a folio-sized book with a laced-case parchment binding, with five double sewing supports, red-sprinkled edges and endbands with green and brown threads, with tiedowns. More crucially, this book has flyleaves with the same watermark as the flyleaves found in the N-A set, suggesting it was made by the same binder around the same time.Footnote 79 The Haarlem book shows signs of restoration which may have involved the removal of membra disiecta and the hand responsible for writing the shelfmark ‘168 B 4’ on the N-H fragment is the same hand that wrote this shelfmark on the inside of the binding of this copy of Eusebius (as can be gleaned from the distinctive capital B). In other words, contrary to Derolez’s claim, it is not at all unlikely that N-H was, in fact, removed from the binding of this particular book, given the book’s similarity to the books in which the N-A fragments were found.Footnote 80

If the Eusebius book in Haarlem was indeed the host volume of N-H (and there appears to be little reason to dismiss the pencilled shelfmark on N-H), there is another possible link with Leiden. The Haarlem copy of Eusebius’s De euangelica praeparatione has a companion volume with a matching laced-case parchment binding and matching flyleaves: a copy of Eusebius’s Historia ecclesiastica in Greek (Paris: Robertus Stephanus, 1544).Footnote 81 These two books can be identified with two titles in the catalogue of the Leiden book auction of Daniel van der Meulen’s library of 4 June, 1601: ‘Eusebii Euang. præparat. Græc. ex Bibliot.reg.Lut. 44 / Eiusdem Ecclesiast. Historia’.Footnote 82 An annotated version of the book sale catalogue from the archive of Andries van der Meulen shows that these books were sold together, for the price of 17 guilders and 2 stivers.Footnote 83 Given all of the above, it seems probable that the two volumes now in Haarlem were bound at the same time in Leiden following the auction on 4 June, 1601, and a piece of the N-Psalter, N-H, was used in the binding of the first volume.Footnote 84

Summing up thus far, information gathered from the host volumes of N-E and N-A, as well as the potential host volume of N-H, points towards Leiden as the most plausible location for the bookbinder who used an eleventh-century Latin psalter with Old English glosses in his workshop. Since Leiden was an international student hub, this localisation can also explain why some of these fragments ended up in places far removed from Leiden, such as Elbląg (through Leiden student Samuel Meienreis), Cambridge (notably, one of Meienreis’s Polish friends and fellow Leiden student, Hans von Bodeck, moved to the University of Cambridge in 1602)Footnote 85 and Sondershausen (in the early seventeenth century, most foreign students in Leiden came from protestant Germany).Footnote 86 Two questions remain, however: where did the eleventh-century N-Psalter come from and how did it end up in a Dutch bookbinder’s workshop around the year 1600?

The provenance of the eleventh-century N-Psalter itself may be established on the basis of its similarities to a number of other Old English glossed psalters. In particular, the N-Psalter shows visual similarities to the contemporary Stowe Psalter (F), Vitellius Psalter (G) and Tiberius Psalter (H) in terms of its mise-en-page and decoration, especially the verse-initial capitals in alternating colours red, green and blue. As described above, the Old English glosses are closely related to D (the Regius Psalter), as well as F, G and J (the Arundel Psalter). According to the overview by Pulsiano, each of these Old English glossed psalters were probably written in Winchester, between 1050 and 1075 (with the exception of the tenth-century D): ‘almost certainly from Winchester’ (D); ‘assigned by Sisam and Sisam … to south-western England, but by Turner … to New Minster (Winchester)’ (F); ‘probably in Winchester’ (G); ‘Winchester, probably Old Minster’ (H); and ‘probably at Winchester (New Minster)’ (J).Footnote 87 Given the similarities between these psalters and the N-Psalter, it is therefore tempting to assign the latter to Winchester as well, although some of the localisations are contested and Exeter may also be a possibility.Footnote 88 If all these psalters can indeed be assigned to Winchester, this means that about half of the extant glossed Psalters from this period came from two or three scriptoria in the same place.Footnote 89

How the N-Psalter from southern England ended up in a Dutch bookbinder’s workshop is a matter of speculation. It is possible that this psalter was one of the many Catholic books that were shipped to the Continent after the Reformation in England. In a famous quote, John Bale lamented in 1549 the treatment of manuscripts after the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–42), which included selling shiploads of English parchment to bookbinders in Europe:

But to destroye all [libraries] without consyderacyon, is and wyll be unto Englande for euer, a moste horryble infamy amonge the graue senyours of other nacyons. A great nombre of them whych purchased those superstycyouse mansyons, reserued of those lybrarye bokes, some to serue theyr iakes, some to scoure theyr candelstyckes, and some to rubbe their bootes. Some they solde to the grosser and sope sellers, ⁊ some they sent ouer see to the bokebynders, not in small nombre, but at tymes whole shyppes full, to the wonderynge of the foren nacyons.Footnote 90

The N-Psalter may well have been one of the victims of this sixteenth-century anti-Catholic libricide, although a more spectacular backstory has been suggested for the N-Psalter by Gneuss.

Gneuss raised the tantalizing possibility that the N-Psalter may be identified as the ‘Gunhild Psalter’ that had once belonged to Gunhild (d. 1087), sister of the ill-fated King Harold Godwinson.Footnote 91 Following the Norman Conquest, Gunhild had taken refuge in Flanders and, in 1087, donated her Latin Psalter with Old English glosses to the church of St Donatus in Bruges.Footnote 92 This book, listed as ‘Item psalterium Gunnildis expositum in anglico’ in the thirteenth-century library catalogue of the chapter of St Donatus,Footnote 93 was last mentioned in 1561 by Jacques de Meyer in his Commentarii sive Annales rerum Flandricarum. De Meyer describes Gunhild’s 1087 donation to the church of St Donatus, including her ‘psalterium, quod et hodie vocamus psalterium Gunnildis, Latinum quidem, sed cum enarrationibus linguæ Saxonice, quas hic nemo satis intelligit’ [psalter, which today we still call the Gunhild Psalter, certainly in Latin, but with explanations in the Saxon language, which no one here can quite understand].Footnote 94 Since then, there has been no trace or mention of the Gunhild Psalter. Opalińska et al. offer the suggestion that the manuscript may have been lost when the church of St Donatus was destroyed in 1804.Footnote 95 Another possible and perhaps more likely scenario is that the Gunhild Psalter fell prey to the Calvinists who took control of the city of Bruges between 1578 and 1584. During this period, they founded a ‘publique librairie’ and on 10 October 1578, they started to confiscate books from monasteries, abbeys and chapters – the best were kept for the public library and the rest were to be sold.Footnote 96 The books of the chapter of St. Donatus were confiscated on 13 December 1580, and if the Gunhild Psalter was among these books, it was most presumably sold rather than included in the public library, given its puzzling Saxon glosses that no one could understand.

Whether shipped in from England or sold out of Bruges, the eleventh-century English N-Psalter ended up in a Dutch bookbinder’s workshop around the year 1600. That workshop was probably located in the university town of Leiden. There, the psalter was cut into pieces, which were then used to reinforce the bindings of scholarly books in Greek, Latin and Hebrew. One of these books was a Hebrew grammar that belonged to a student from Elbląg, Poland; two other books had been purchased at a Leiden book auction on 4 June 1601 and eventually made their way to the municipal library of Haarlem; and a four-volume Greek dictionary was bought during a book buying expedition by Alkmaar notables who had attended that same auction in 1601. Some four centuries later, fragments of the N-Psalter are beginning to reemerge from these early modern book bindings and can now once again be reassembled.Footnote 97

ANNOTATED EDITION OF THE ALKMAAR FRAGMENTS

Text in italics indicates expanded abbreviations; letters between round brackets () are only partially visible. Missing Latin text is reconstructed on the basis of the Stowe Psalter (F) and given between square brackets. Missing or incomplete Old English glosses are not reconstructed. A dash – in the line of Old English glosses indicates a word that is present in the Latin text has not been glossed.

Funding Statement

Part of the research in this article was made possible by a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO); grant number: 406.XS.01.006.

Appendix A: Significant Variant Readings of the Old English Gloss

The tables below include selections of significant variant readings within the extant Old English glossed psalters. Correspondences between N-A and other extant Old English psalter glosses may be useful in establishing links between these manuscripts.

Generally, the N-A gloss corresponds with both F and G, but it is not a direct copy of either. The first two tables are overviews of variant readings where N-A corresponds to G, but not with F; the next two tables show where N-A provides glosses that match F, but differ from G. The last table in this appendix demonstrates where N-A varies from both F and G and generally follows D.

Variant readings that only concern minor matters of spelling of, e.g., the suffix -nes are not included (N-A generally has the spelling -nes, as opposed to -nis A and -nys CF). In the tables, spelling variants are given as they appear in the standard editions of the Old English glossed psalters, but whenever two psalters only differ in their use of ð and þ, these readings have been conflated.

LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN N-A AND G, NOT SHARED WITH F

OTHER CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN N-A AND G, NOT SHARED WITH F

LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN N-A AND F, NOT SHARED WITH G

OTHER CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN N-A AND F, NOT SHARED WITH G

GLOSSES WHERE N-A CORRESPONDS TO NEITHER F NOR G, BUT GENERALLY FOLLOWS D

Appendix B Old English glosses that are unique to N-A

The table below shows the Latin and Old English readings from N-A, alongside the corresponding Old English glosses in the other psalters. These Old English glosses have no equivalents in the other psalters. Spelling variants are given as they appear in the standard editions of the Old English glossed psalters, but, if two psalters only differ in their use of ð and þ, these readings are conflated.

Appendix C Collation of Latin text

The table below shows distinctive Latin readings from N-A, alongside the corresponding readings from the Psalterium Romanum and the Psalterium Gallicanum,Footnote 171 as well as any alternative Latin readings found in other glossed Psalters. Underlined forms indicate the ones which correspond to the Latin readings in N-A. Whenever the Romanum and Gallicanum give the same reading, the two columns have been merged and the form they provide has been centred – these shared readings have only been included if there was an alternative in any of the other glossed Psalters. Variation within the psalters between ae, æ and ę has not been taken into account and forms with æ are used throughout this overview (except when N-A uses ę); variation between u and v is also ignored.