This special issue brings together archaeological and epigraphic evidence and interpretations by scholars who have been focusing on the subject of the Classic Maya Kaanuˀl kingdom in recent decades (for Kaanuˀl spelling explanation see Supplementary Text 1). Based on what we know now, the Kaanuˀl's was a hegemonic state that ruled over most of the Maya Lowlands for at least two centuries, from circa a.d. 500 to circa a.d. 700 (Figure 1). Its beginnings, processes of territorial expansion, and internal functioning have remained largely obscure in spite of a vast epigraphic record documenting a far-reaching sphere of influence.

Figure 1. Map of the Maya Lowlands showing sites affiliated with the Kaanuˀl hegemony (black), other unaffiliated sites or sites of unknown affiliation, and area of hypothetical maximum hegemony extent (approximately 210,000 km2).

For a long time, Classic Lowland Maya society was believed to have never been politically unified but fragmented into competing segmentary and volatile city-states (Demarest Reference Demarest, Demarest and Conrad1992; Fox et al. Reference Fox, Cook, Chase and Chase1996; Mathews Reference Mathews, Willey and Mathews1985), although a few scholars considered regional states possible (Adams and Jones Reference Adams and Jones1981; Marcus Reference Marcus1973, Reference Marcus1976). Since the 1990s, the idea that the Late Classic (a.d. 600–900) Tikal and Kaanuˀl kingdoms were large hegemonic states has come to take hold, and having been supported by mounting evidence, it is now generally accepted (Culbert Reference Culbert1996; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube1995, Reference Martin and Grube2008[2000]; Martin and Velásquez Reference Martin and Velásquez2016; Sharer and Traxler Reference Sharer and Traxler2006). Because more is known about the history of the Kaanuˀl kingdom than of any other polity due to a greater abundance of texts from the Late Classic period referring to it, it has been the focus of attention by scholars interested in the study of this unusual form of Maya state (Martin Reference Martin2020). The available information is largely concentrated to the last century of the hegemony from circa a.d. 630 to 730, the period in which more kingdoms in the Maya Lowlands produced texts than at any other time, thereby attracting scholarly research. During that time, Calakmul was the capital of the hegemony. As a result, much of what we know about the configuration of the hegemony is skewed toward this late period and toward Calakmul as its capital. Much less is known about what led to its emergence and organization. This research bias has permeated our literature for decades, to the point that, at times, the terms Kaanuˀl and Calakmul are used interchangeably, obscuring the important fact that the royal court was established at Dzibanche before and after Calakmul, as will become evident to the reader of this special section.

The Kaanuˀl kingdom owes its name to a snake-head hieroglyphic title appearing at a variety of lowland sites between a.d. 550 and a.d. 731, approximately. The location of its capital eluded scholars for some time (Marcus Reference Marcus1976). According to a recent epigraphic study, however, the snake-head sign was used as a toponym—read Kaanuˀl, “place of snakes”—as well as a dynastic title at Dzibanche (Martin and Velásquez Reference Martin and Velásquez2016). In the seventh and eighth centuries, the snake-head emblem glyph was clearly associated with the archaeological site of Calakmul, but not in the fifth and sixth centuries, when it appears on several monuments and in a royal burial at Dzibanche. However, until recently, evidence was lacking for the snake-head emblem being used at Dzibanche or anywhere else prior to the earliest date on hieroglyphic stairway I, which is now believed to be a.d. 408 (Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024; see also Velásquez Reference Velásquez and Nalda2004, Barrientos et al. Reference Barrientos, Canuto and Suart2024). As a result, the problem of the origin of the dynasty has been the subject of several theories. According to one, the Snake dynasty had roots in the Preclassic period, and originated at El Mirador, located 160 km southwest of Dzibanche (Hansen and Guenter Reference Hansen, Guenter, Fields and Reents-Budet2005). The discovery of Ichkabal, a large Preclassic center near Dzibanche has led some to suggest that it may instead be the place of origin for the Kaanuˀl dynasty (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia [INAH] 2009; Martin Reference Martin2020). We address potential links between Dzibanche and Ichkabal elsewhere (Balanzario and Estrada-Belli Reference Balanzario and Estrada-Belli2021), while several articles in this issue reject the alleged links between El Mirador and the origins of the Kaanuˀl dynasty.

Here, we focus on connecting what is known about the dynasty's early history with the archaeology of Dzibanche. Other contributors to this special issue offer insights about the relocation of the dynasty to Calakmul (Helmke and Vepretsky Reference Helmke and Vepretskii2024; Martin Reference Martin2024), as well as a new epigraphic assessment of the early dynastic period at Dzibanche and of its expansion, which may have begun earlier than previously thought (Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024). Additional details on this subject come from Naranjo, Peten, where the installation of the boy-king Ajnuumsaj in a.d. 546 established one of the strongest and longest-lived Kaanuˀl allies, as well as from La Corona and El Peru, where, beginning in circa a.d. 520, the Snake kings established multigenerational bonds by marriage (Barrientos et al. Reference Barrientos, Canuto and Suart2024; Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly and Freidel2024; Tokovinine, Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Tokovinine, Estrada-Belli and Fialko2024). One lingering question about these and later unions between Kaanuˀl royal women and vassal lords is whether military conquests may have preceded them. In this sense, the display of military might in Dzibanche's hieroglyphic stairway I (Velásquez Reference Velásquez and Nalda2004, Reference Velásquez and Stuardo2008; Velásquez and Balanzario Reference Velasquez and Balanzario2024; see also Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024) and evidence of architectural defacing and of the interruption of royal lines at Naranjo and Holmul are suggestive (Tokovinine, Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Tokovinine, Estrada-Belli and Fialko2024).

Another important theme related to warfare that several articles in this volume touch on is that of the relationship between Kaanuˀl and Teotihuacan. This is materialized in the monuments and architecture of Dzibanche (Figures 2 and 21, Figure S1), as well as in its royal burial offerings and epigraphy (see below; see also Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024), and it is an aspect of the early history of the Kaanuˀl kingdom that has received relatively little attention (but see Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda, Balanzario, Fournier, Wiesheu and Charlton2007). The references to Teotihuacan continued through the Late Classic period as a new royal line was initiated at Calakmul. Long after Teotihuacan's political influence in Mesoamerica had ended, Kaanuˀl kings displayed Teotihuacan-related war insignia and modeled themselves after legendary Teotihuacan figures of the Early Classic period (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly and Freidel2024; Stuart Reference Stuart2020).

Figure 2. Teotihuacan-style talud-tablero architecture at Dzibanche, ca. a.d. 500–550. Lintel Pyramid (Building 6) (left) and Cormoranes Pyramid (Building 2) (right). Photograph by Estrada-Belli.

Textual evidence from Dzibanche suggests that by the early fifth century, kings using the snake-head title overtook several other kingdoms (Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024; Velásquez Reference Velásquez and Nalda2004, Reference Velásquez and Stuardo2008). At that time, Teotihuacan-style elements decorated at least three pyramids at Dzibanche (Buildings 6 [Lintel], 2 [Cormoranes], and Tutil 2, see below). By the 550s, the Kaanuˀl kings had been active as overlords at such distant sites as La Corona, Naranjo, and El Peru, Peten, adopting the emperor-like title of “kaloˀmteˀ’’, previously exclusive to the fourth-century Teotihuacan emissary Sihyaj K'ahk’ and to Teotihuacan's putative ruler Jatz'oˀm Kuy, whose personae had clear militaristic connotations (Beliaev and Houston Reference Beliaev and Houston2020; Martin Reference Martin2020; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008[2000]; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1993:28–33; Stuart Reference Stuart2020).

One important subject, which is also related to the question of origins, has been the Kaanuˀl dynastic sequence and peculiar modalities of succession. Retrospective inscriptions on looted vases from the Calakmul region bear multiple versions of a Kaanuˀl king list (see Martin Reference Martin2024). The list includes dates of accession from the founder to seventh-century Ruler 19, albeit given in ambiguous 52-year-cycle form. Some of them, however, differ from those associated with the same names on stone monuments. This has raised many questions about the accuracy of the list's chronology, leading some to suggest that the dates may include errors or overlaps in rulership (Martin Reference Martin2017). The names of the later kings and accompanying dates match contemporary monuments and are readily recognizable. Some of the earlier names, however, appear to be unknown, or are homonyms of later rulers. Because of the ambiguity in the dates and lack of corroborating mentions from other sources, it has been difficult to place them into a sequence. These ambiguities initially suggested that the king list may not be a historical document, but one that includes mythical figures (Helmke and Kupprat Reference Helmke, Kupprat and Grena-Bahrens2016: Martin Reference Martin and Kerr1997) or rulers from a distant Late Preclassic past (400 b.c.–a.d. 250) linked to the great Preclassic El Mirador center (Hansen and Guenter Reference Hansen, Guenter, Fields and Reents-Budet2005). Nevertheless, using a standard method for establishing dynastic chronological depth, Martin (Reference Martin2017) has convincingly proposed that the founding of the dynasty occurred around a.d. 200. Consequently, the beginning of the Kaanuˀl dynasty would have occurred after the collapse of El Mirador and within about 100 years of Tikal's first known ruler, which is the earliest historic dynastic foundation known so far.

Recently, Martin and Beliaev (Reference Martin and Beliaev2017) have identified the name of the first Kaanuˀl ruler to use the title of kaloˀmteˀ: K'ahk’ Tiˀ Ch'ich’. The text on Dzibanche's wooden lintel 3 (Gann Reference Gann1928) appears to commemorate his taking the title in a.d. 550 as well as the dedication of the eponymous temple, one of the most important at the site, leaving no doubt that Dzibanche was the capital of the kingdom at that time (see also Martin Reference Martin2017, Reference Martin2024). He also appears as overlord and “eastern kaloˀmteˀ” at Chochkitam, in northeastern Peten, in a.d. 568, confirming that he was still the supreme authority in apparent overlap with another ruler, known as Sky Witness, since a.d. 561. This confirms Martin's (Reference Martin2017, Reference Martin2020) hypothesis that at Kaanuˀl, a kaloˀmteˀ high king would overlap with and eventually be replaced by a lower ranking “holy king” upon his death, at which time a new “holy king” would take the junior position, a system of tiered corulership documented in other Classic Maya dynasties, including those of Bonampak-Lakanha, Motul de San Jose (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013; Tokovinine and Zender Reference Tokovinine, Zender, Foias and Emery2012; Velasquez Reference Velásquez2011), and Tikal (Harrison Reference Harrison1999:79). This also implies that K'ahk’ Tiˀ Ch'ich’ may have led the a.d. 562 war against Tikal instead of Sky Witness, as recently proposed by Martin and Beliaev (Reference Martin and Beliaev2017; Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine2022).

A previously unreported miniature stela found in the termination fill of Dzibanche's Late Classic Pom Plaza palace, discussed for the first time by Tokovinine, Beliaev and colleagues (Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024) in this issue, portrays a Kaanuˀl ruler from the late fourth century listed on the dynastic vases, further demonstrating the validity of those king lists and that the dynasty has a long history at Dzibanche. In addition to this evidence, at least two royal burials at Dzibanche, whose occupants are not identified by any accompanying text, could be those of members of the Kaanuˀl dynasty from around a.d. 400 (see below). It should be noted here that this new monument from Dzibanche predates any Kaanuˀl textual evidence from El Mirador, thereby making that dynastic origin hypothesis wholly untenable. At Dzibanche, there are currently no texts or burials related to members of the Kaanuˀl dynasty from a.d. 200 to circa 381 to match the earliest royals listed on dynastic vases. Nevertheless, given that many of the site's large structures remain unexcavated, and that the dynasty is named after Dzibanche's original place name, we feel that the likelihood is good that burials of the earliest rulers will be found there.

One additional question that will be dealt with in the following pages is how what is known about Dzibanche as a city might relate to its role as the capital of a kingdom of unusual political reach. Prior reports have described the main features of its urban setting focusing primarily on the monumental architecture, with some emphasis on its relationships with nearby centers (Nalda Reference Nalda and Morlet2000; Nalda and Lopez Reference Nalda and Lopez1995). Thanks to a recent lidar survey, it is now possible to revisit Dzibanche's urban characteristics with an eye to its organization as a center of great political power, population density, and economic activity.

Maya urbanism at Dzibanche

The archaeological site of Dzibanche was first reported by British colonist Thomas Gann in 1927. He named the site after the inscribed wooden lintel in Building 6 and recognized that Dzibanche and Kinichna were parts of a single ceremonial center (Gann Reference Gann1927, Reference Gann1928, Reference Gann1935). Peter Harrison's (Reference Harrison1972) Uaymil regional survey included Dzibanche and located a few of the surrounding minor centers (Figure 3). In 1987, INAH archaeologist Enrique Nalda undertook the first major excavation project at Dzibanche, which continued into the 1990s and again in the 2000s until his untimely passing in 2010 (Nalda Reference Nalda2004; Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2001–2009; Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999). This research showed that Dzibanche's monumental zone was composed of four major monumental groups, Kinichna, Tutil, Lamay, and Dzibanche's Main Group (Figure 4). Dense residential areas were interspersed over an area of approximately 20 km2, which he estimated to extend further beyond his survey. Nalda also noted that the causeways connecting the groups formed a triangular network, with Kinichna as the possible principal node due to a greater number of causeways radiating from it. Around this core area were several reservoirs. One of the largest was the Aguada de los Patos, measuring 4 ha in area, situated next to Dzibanche's Main Group (Nalda Reference Nalda2004).

Figure 3. Map of the putative Dzibanche heartland region in southeastern Quintana Roo showing nearby centers linked by causeways and other currently known sites possibly affiliated with the Kaanuˀl kingdom. Image by Estrada-Belli; terrain data by NASA-SRTM mission.

Figure 4. Lidar map of the Dzibanche urban core, highlighting causeways, reservoirs, as well as upland (green) and wetland (blue) fields. Image by Estrada-Belli; lidar data by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

The city itself sits on a low upland ridge just west of the very prominent Cerro de la Tortuga (Figure 3). Farther to the east, the settlement is dense again near the Preclassic center of Ichkabal and beyond. Ichkabal boasts pyramids and plazas rivaling those of El Mirador in size (Balanzario and Estrada-Belli Reference Balanzario and Estrada-Belli2021). The zones of highest residential density are located within the Dzibanche triangular core and in a cluster just north of Ichkabal, in correspondence with a Classic-period plaza complex known as Oxnahb (Figure 5). The currently mapped settlement covers an upland area of 65 km2, but, as Nalda (Reference Nalda2004) noted, it likely extends to the southwest, in the direction of one of the Classic-period centers linked by causeway, Pol Box (12 km), as it does to Mario Ancona (15 km) to the northeast. Additional upland zones near Dzibanche have dense settlement around the centers of El Resbalón (15 km), Nicolás Bravo (29 km), González Ortega (20 km) and Ucum (29 km), which have architectural layouts imitating Dzibanche's and, based on excavations by Balanzario, appear to have overlapped in time with Dzibanche (Figure 3; Lopez Reference Lopez, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejia2005; Nalda and Lopez Reference Nalda and Lopez1995). Currently, we cannot establish with any degree of confidence the actual extents of the city and of its apparently vast hinterland until a larger area is mapped to include upland zones beyond the current 103 km2 survey, although based on prior field surveys and satellite imagery, it is estimated that all uplands between Dzibanche and those smaller centers may have been densely settled and all surrounding wetlands cultivated.

Figure 5. Image map of Dzibanche showing density zones and settlement features recorded on lidar. Image by Estrada-Belli terrain data by NASA/SRTM; lidar data by INAH.

The area of highest structure density (150–550 structures per km2) around the four major Dzibanche complexes, which may be described as a purely urban zone, measures 15 km2 (Figures 4 and 5). By comparison, Tikal's equally defined urban zone measures 10 km2. Overall, the 65 km2 zone of settlement surrounding the city, within the 103 km2 lidar survey (63% of surveyed area) is estimated to be comparable in size to Tikal's, which extended over 76 km2 within a 147 km2 survey (51% of surveyed area) and was probably home to approximately 39,000 to 56,000 people (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drápela, Lieskowský, Tokovinine, Velásquez, Fernandez-Diaz and Shrestha2018:10, Table 6). The structure density also appears to be relatively similar in the two survey zones: 6,073 structures in the nearest 65 km2 (i.e., 93 structures/km2) at Dzibanche, 12,341 structures in the nearest 147 km2 (i.e., 84 structures/km2) at Tikal (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drápela, Lieskowský, Tokovinine, Velásquez, Fernandez-Diaz and Shrestha2018:Table 4). However, more survey coverage at both sites will be needed to include neighboring upland areas before a full comparison can be made between these two cities. Based on excavations and epigraphic data from the monumental core, limited excavation and survey in the residential zones, and analysis of settlement patterns observed on lidar maps consistent with contemporaneity, it is believed that Dzibanche reached its population maximum at the very beginning of the Late Classic period (ca. a.d. 600–630), likely following the victory over Tikal and culminating with the dynastic turmoil of the early seventh century. Tikal did not reach its population peak until two centuries later, after defeating the Kaanuˀl and their allies (ca. a.d. 750–800). What is known today about the extents of Tikal's monumental zone and residential settlement of the Early Classic period suggests that they were significantly smaller than in the ninth century (Culbert et al. Reference Culbert, Kosakowsky, Fry, William, Culbert and Rice1990; Fry Reference Fry, Culbert and Rice1990; Lentz et al. Reference Lentz, Dunning, Scarborough, Magee, Thompson, Weaver, Carr, Terry, Islebe, Tankersley, Sierra, Jones, Buttles, Valdez and Ramos Hernandez2014; Webster Reference Webster2018).

A comparison of the monumental cores of ninth-century Tikal and seventh-century Dzibanche shows a striking similarity in the general triangular layout of causeways connecting plaza-temple complexes of the two cities but at a stark 1:2 difference in scale (Figure 6). Therefore, based on current evidence, Dzibanche may have been a considerably larger city than Tikal during the Early Classic period.

Figure 6. Lidar image maps of the monumental zones of Dzibanche (left) and Tikal (right) compared at 2:1 scale difference. Image by Estrada-Belli; Dzibanche lidar data by INAH; Tikal lidar data by PACUNAM Lidar Initiative.

Internally, Dzibanche's urban composition was as complex as one would expect of a city with a large population of different social strata. The largest and more elaborate residential groups were concentrated in the areas surrounding the four major ceremonial nodes forming two large zones of high structure density (Figures 4 and 5). At the top of the structure-size scale were the royal compounds surrounding the main plazas. Elite compounds were progressively less imposing and complex as one moved outside of the urban zone. Within the urban zone, structures were more closely spaced than outside of it, suggesting that residents had to rely on agricultural production farther afield. Accordingly, just outside the urban zone, especially to the north and northeast, were large expanses of “delimited fields”—stone-wall enclosures that appear to be of standard size (0.5–1.0 ha on average) that increased as one moved out to more sparsely populated zones. Enrique Nalda (Reference Nalda2004) had interpreted them as household properties. This type of enclosures and hillside terraces have been documented in many parts of the Maya Lowlands, especially since the advent of lidar surveys (Fedick Reference Fedick1996; Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Dunning, Cook, Ruhl, Barth and Conley2021).

In the wetlands to the north and south of Dzibanche, the grids formed by the wetland fields have consistent axial orientation (12–15o east of north) similar to that of some of the temples in the Main Group and to the central causeway linking the Lamay and Kinichna complexes. The grids also feature near-standard cell size (in a test sample of 218 fields, 79 percent measured between 400 and 1500 m2), suggesting coordination and contemporaneity (Figure 7; see also Harrison Reference Harrison, Harrison and Turner1978). Due to their proximity, it is likely that a good percentage of wetland production was extracted by the elite as tribute. It is also likely that a portion of it, after subsistence and tribute, was exchanged in local markets. However, the degree to which wetland production was directly managed by the elite may have been limited based on what is currently known about the overall involvement of elites in Maya economy (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020). In the Guatemalan Peten region, the association of wetland intensive agriculture and large urban centers, where most of the population was unable to farm, has been linked to some elite involvement in the management of production and distribution (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drápela, Lieskowský, Tokovinine, Velásquez, Fernandez-Diaz and Shrestha2018:7).

Figure 7. Image map combining 2017 lidar survey data and 2019 infrared multispectral satellite data of Dzibanche's wetlands showing patterns of gridded raised fields and the histogram of a sample of wetland field area (insert). Image by Estrada-Belli; lidar data by INAH; multispectral data by ESA/Copernicus.

Dzibanche had at least one central marketplace, near the entrance to the Main Group, at the terminus of the 100 m-wide Avenue of the Kings from Lamay into the Main Group's royal courts (Figure 8). Two large ballcourts were also located in this area. Although the central market may have been the city's most important point of exchange, there may have been many smaller markets within the periurban zone to which the general population may have had access on a more regular basis. Although this has long been a contentious subject in Maya archaeology, there is now widespread consensus that markets were an important component of Classic Maya settlement (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020). Some scholars have suggested that major peripheral elite compounds, especially those with larger plazas served by causeways, may have functioned as district marketplaces (D. Chase and A. Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020; Ruhl et al. Reference Ruhl, Dunning and Carr2018). At Dzibanche, there are several groups that qualify as potential district marketplaces based on plaza area, presence of elite structures, and clustering of smaller residences around them. When the top elite groups so defined within the 103 km2 survey zone are taken into consideration and we count structures around them, we find that a vast majority of the residential population lived within 1 km of these groups. If markets were hosted there, nearby residents would have had easy access (Figure 5). The residences’ clustering around major elite groups is also suggestive of potential underlying processes related to land and labor allocation in the settlement zone as well as to defining neighborhoods, a pattern that has been rather elusive elsewhere (Hutson Reference Hutson2016; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier, Arnauld, Manzanilla and Smith2012; Lemonnier and Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013; Smith Reference Smith2011; Yaeger Reference Yaeger, Canuto and Yaeger2000). One possibility is that the elites residing in those groups had some control over the distribution of land and labor around them. Although this interpretation remains preliminary, it should be noted that Dzibanche appears to have grown little after its peak in the early Late Classic period, and as a result, on lidar images, its settlement patterns appear quite consistent. This is perhaps due to the settlement being less altered by later changes in spatial organization than at other Maya sites with more complex landscape palimpsests.

Figure 8. Lidar image map in 3D of Dzibanche's Main Group showing major plazas and buildings (viewed from south). Image by Estrada-Belli; lidar data by INAH.

Access to water in the city and hinterland is another aspect that may reveal centralized planning. At Dzibanche, access to water appears to have been structured to minimize water shortages for the general population. It is generally thought that the daily needs of Maya households outside site centers may have been satisfied by domestic storage facilities, such as chultuns (cisterns) and/or former quarries converted into small reservoirs and fed by rainfall (A. Chase Reference Chase2012, Reference Chase2016). Although Dzibanche's periurban settlement may have been no exception to that, it is likely that cisterns would not have been feasible for every household within the densest urban zones. Unfortunately, we cannot estimate how many households would have had cisterns at Dzibanche because they are largely indistinguishable on current lidar maps, although we encountered some during field survey. There are, however, many monumental reservoirs located at the edge of the Dzibanche core area and within the outer periurban zones. The Aguada de Los Patos, for example, would have served the higher elite and a good portion of the urban core around the Main Group. Likewise, the urban residents surrounding the Tutil Group, would have been served by the Western Aguada, a reservoir measuring a staggering 5.4 ha (Figures 4 and 5). If we consider the distribution of monumental reservoirs throughout the 103 km2 of mapped settlement, we find that nearly 100 percent of the population lived within a 1.5 km distance of a major reservoir and therefore had easy access to water even during periods of scarce rainfall, when household cisterns may have been dry. An additional source of water could have been found further afield in natural pools along the Río Escondido during dry seasons.

An important element of urban organization is connectivity infrastructure. At Dzibanche, the four main ceremonial groups were connected by 2–2.5 km long causeways. These causeways appear to be largely ritual in function. Other causeways may have served more practical purposes, such as access to markets, to water, or to peripheral plaza groups, as noted earlier. Most plaza groups outside the central urban zones were connected by a network of causeways reaching to the northeast as far as Ichkabal (11 km) and Mario Ancona (15 km), and to Pol Box (12 km) to the southwest (Figures 3 and 5). We assume that these roads could have served purposes other than purely ritual, including efficiently moving people and goods into the central and neighborhood markets, as well as for military purposes, as noted by Diane Chase and Arlen Chase (Reference Chase, Chase, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020) at Caracol.

Burials, monuments and architecture of the Kaanuˀl dynasty

Enrique Nalda's excavations documented a long occupation sequence at Dzibanche beginning in the Middle Preclassic period (850–400 b.c.), although mostly through redeposited ceramics, with monumental architecture beginning in the Late Preclassic period (400 b.c.–a.d. 250), continuing through the Classic period (a.d. 250–950) and, in diminished form, in the Postclassic period (a.d. 950–1500) as well. Albeit unevenly, Dzibanche was one of the few Maya centers to have been occupied throughout all major eras until the Spanish invasion (Nalda Reference Nalda2004; Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010b).

At Kinichna, Nalda found evidence of Late Preclassic occupation under Early and Late Classic buildings. He noted that abundant Preclassic ceramics were recovered from the surrounding residential structures as well (Nalda Reference Nalda2004). In its final arrangement, the Kinichna acropolis was a multilevel triadic group similar to Early Classic (a.d. 250–550) Peten examples such as Uaxactun Group A-V (L. Smith Reference Smith1950:Figure 66), Río Azul Group A (Adams Reference Adams1999) and Tikal's North Acropolis (Coe Reference Coe1990:Figure 6j–k). The main structure is oriented to the south and flanked by two buildings facing one another, while the lower temples face the plaza (Figure 9). The building roofs feature rectangular recess panels reminiscent of contemporary Teotihuacan-style examples at Tikal and La Sufricaya (Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Estrada-Belli, Tokovinine, Foley, Heather, Ware, Stuart and Grube2009:Figure 15)

Figure 9. Aerial view of Kinichna acropolis. Photograph by INAH.

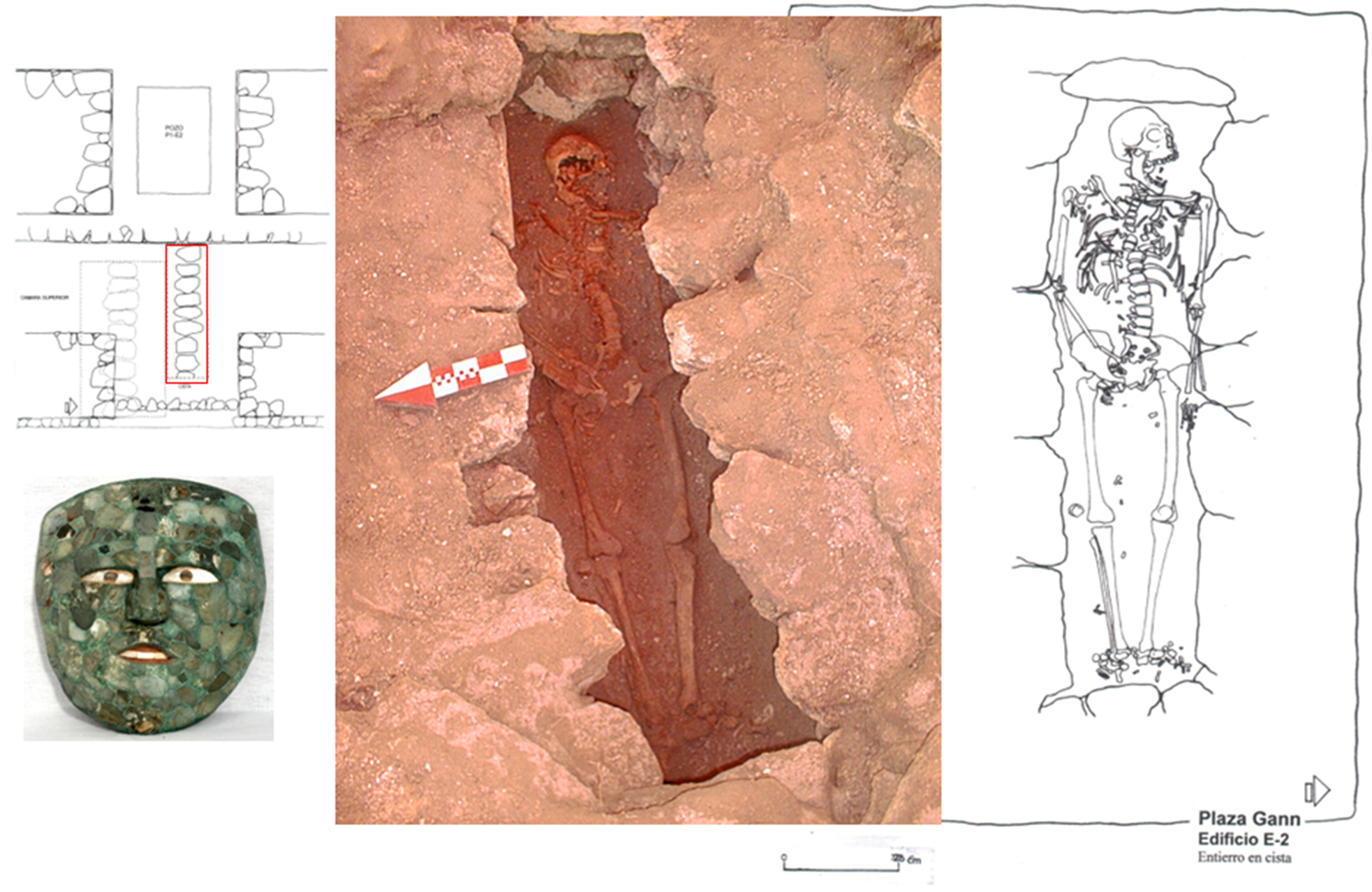

Beneath the main temple was a chamber (Room 102) containing the burials of an older and a younger male accompanied by a jaguar (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999:19–22). Among the many jewels was a jade mosaic mask—the earliest in a series accompanying Kaanuˀl royals—and a Teotihuacan-style jade figurine head (Figure 10). The accompanying Aguila Orange ceramics and the unusual richness of the offerings (see complete artifact list in Supplementary Text 2) suggest that the main individual may have been a ruler from around a.d. 400. It is tempting to speculate that this may have been Yuknoˀm Ch'eˀn I's burial, given its location in the most prominent pyramid at the site, commensurate with the expected status of the leader of Kaanuˀl's early military expansion.

Figure 10. Contents of the royal tomb in the Kinichna main temple. See Supplementary Text 2 for a full list. Drawing and photos by INAH.

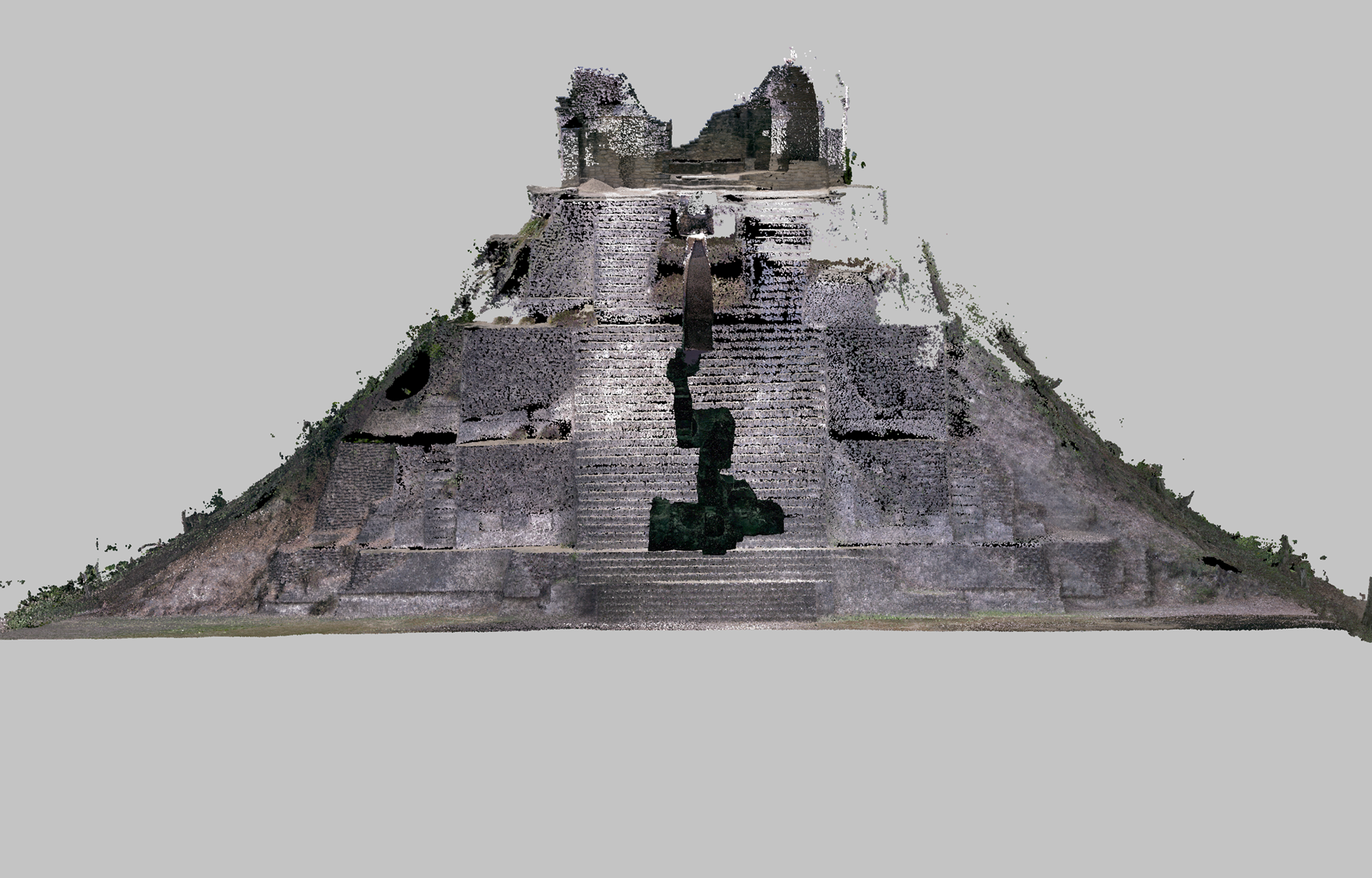

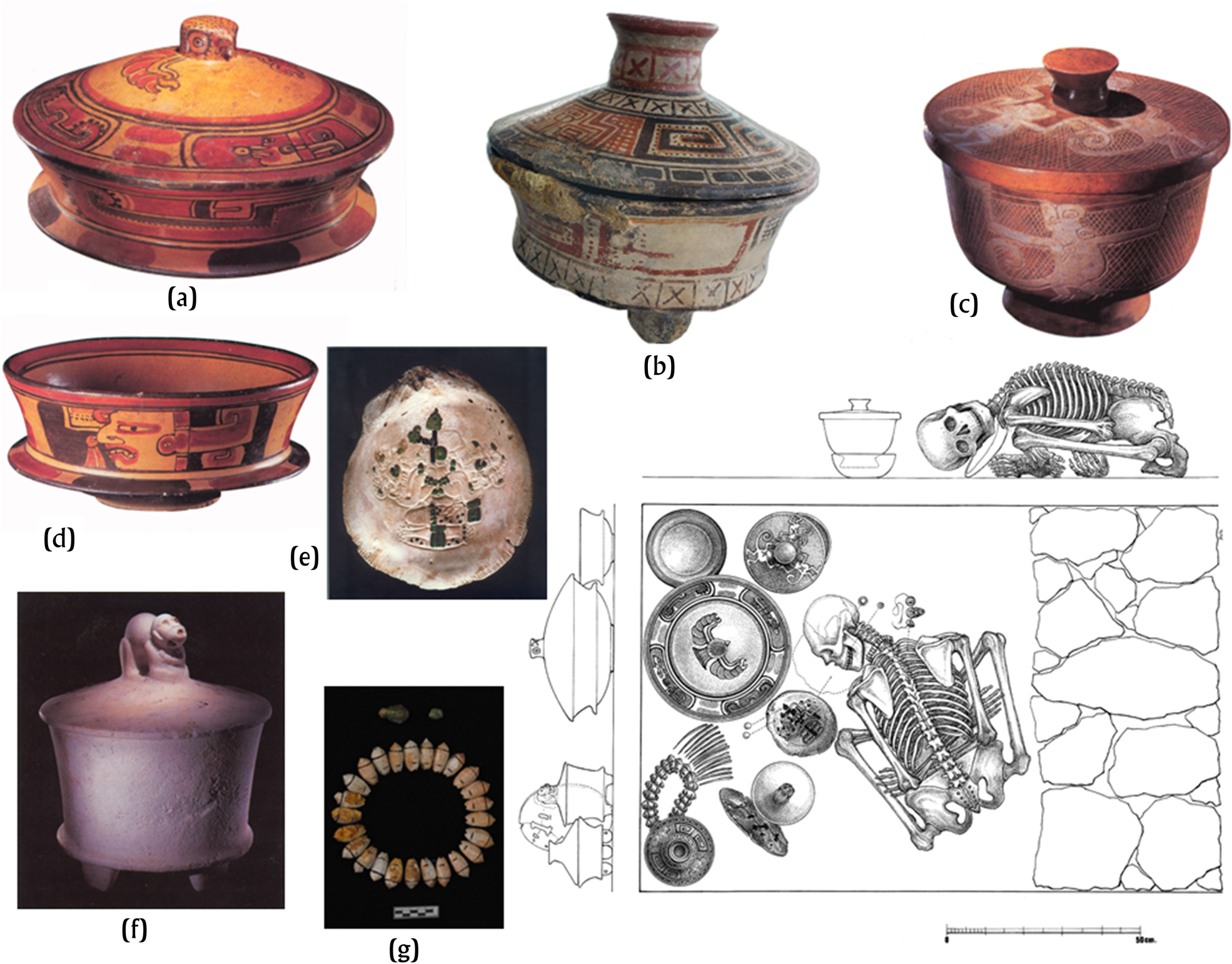

Another likely royal burial from around a.d. 400 was found at the bottom of the Buho Pyramid in the Dzibanche Main Group (aka Building 1; Figure 11; Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999). It contained a woman seated cross-legged accompanied by several high-end Teotihuacan-style vessels, such as a stone cylinder vessel (Figure 12f), a stone bowl, a brown lidded pedestal bowl with incised decorations depicting monkeys (Figure 12c), and two eminently Maya-style Dos Arroyos Polychrome lidded cylinder vessels (Figure 12a–b). The offering included 14 large green obsidian blades, and a large spondylus shell with relief carving of a seated figure wearing the Foliated Ajaw headdress (Figure 12e; see also Supplementary Text 3)— symbol of royal authority—incrusted with jade, pyrite, and black coral (Stuart Reference Stuart and Nalda2004). The skeleton of a male lay outside the tomb's blocked entrance.

Figure 11. Frontal view of 3D scan of the Buho Pyramid (Building 1), showing inner chambers and stairway leading to the tomb at the base of the pyramid. Courtesy of INAH / Eric Lo, and University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

Figure 12. Contents of the Buho tomb. Photos by INAH / Perez de Lara, and INAH / Martinez del Campo (mask). See Supplementary Text 3. Drawing by INAH.

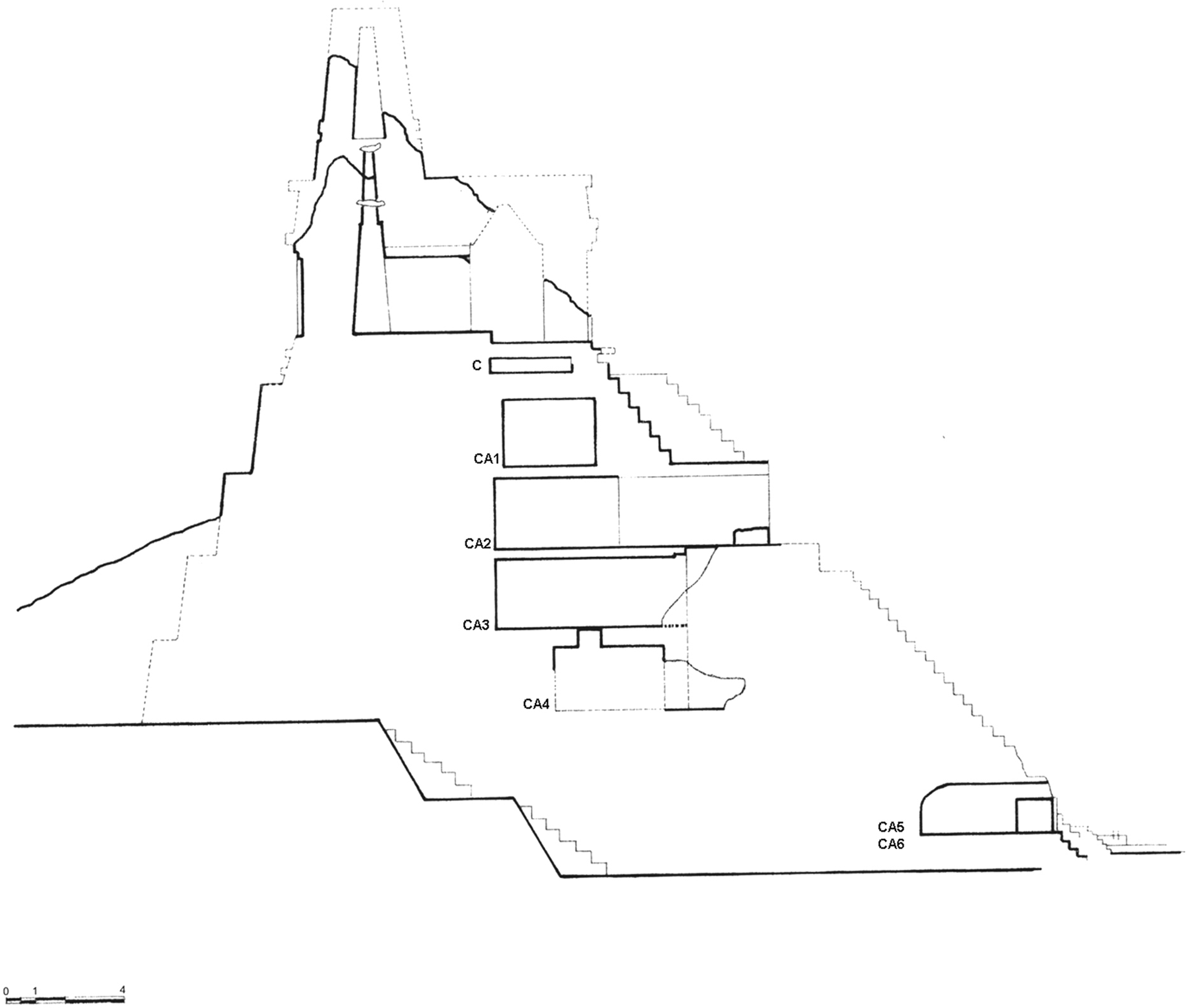

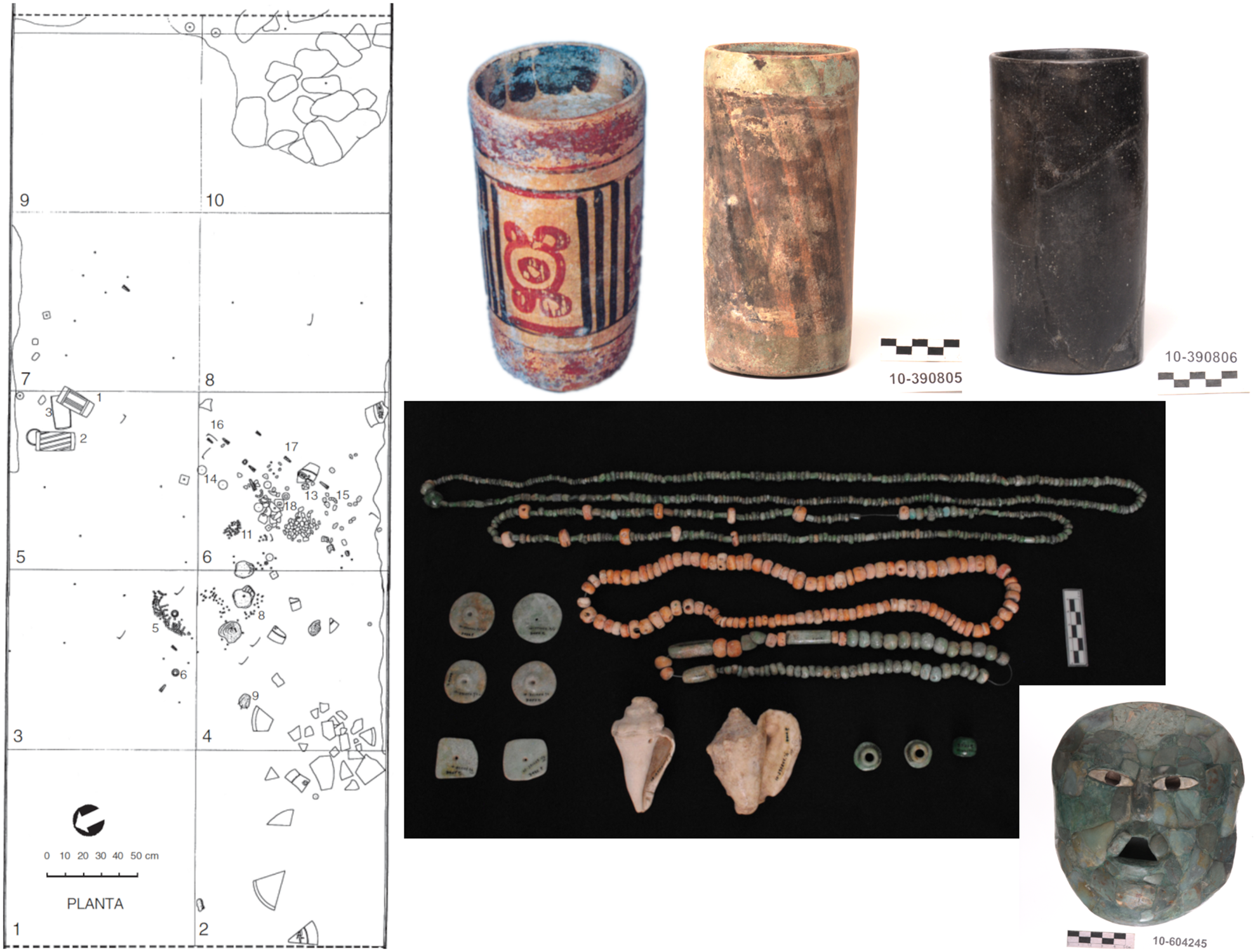

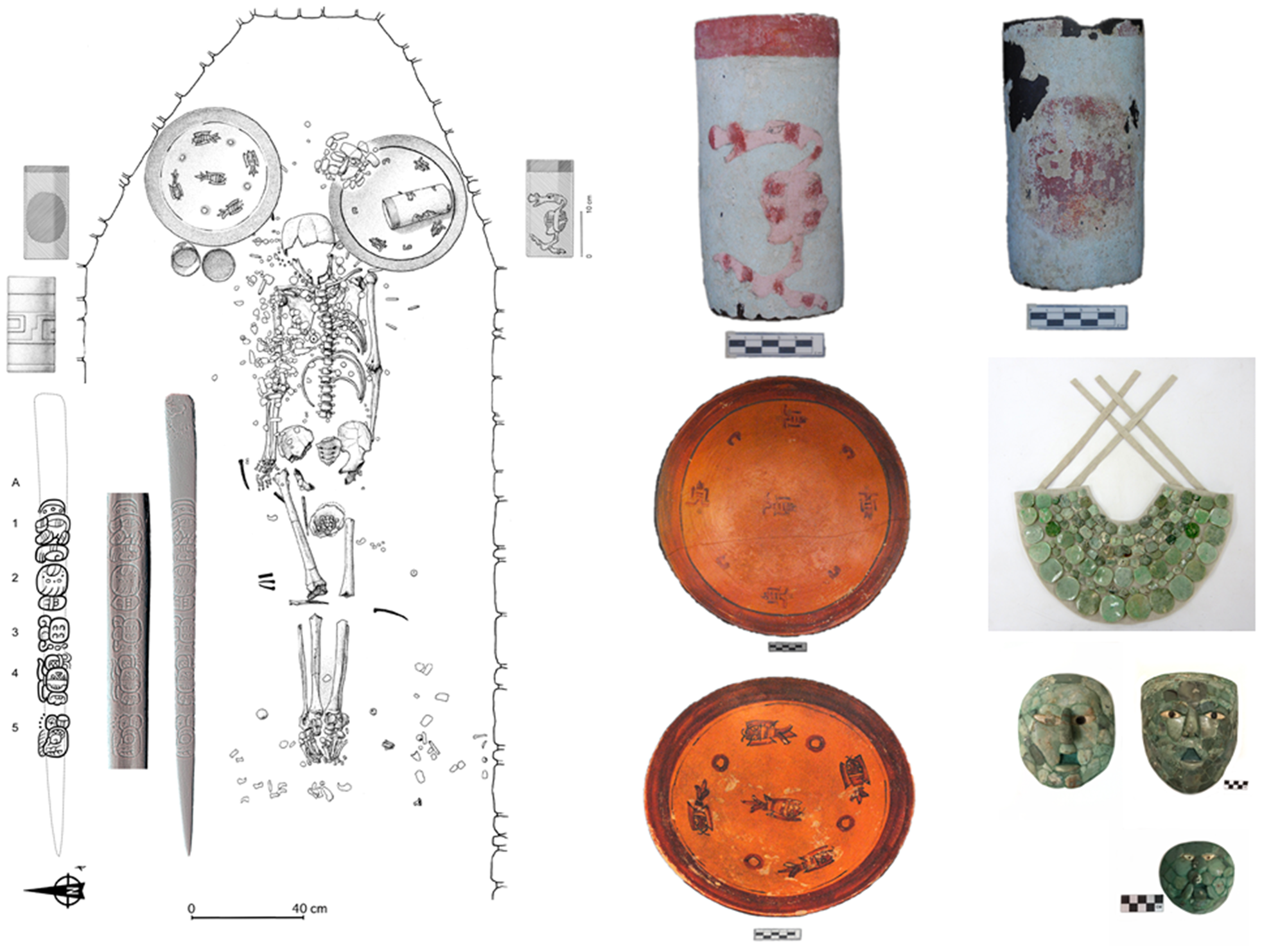

Following a 150-year gap in the burial record are the tombs in the Cormoranes Pyramid (Building 2) featuring jade mosaic masks, which appear to be a distinctive royal attribute of the Kaanuˀl dynasty, and one burial in the Lintel Pyramid (Building 6). All these burials appear to date to the latter part of the sixth and early seventh centuries (Nalda Reference Nalda2003). Because of several alterations, including the removal of sections of the stairway, the stratigraphic order of the Cormoranes tombs is not entirely clear (Figure 13). One of the richest is Room 2, whose vault extended 8 m into the core of the pyramid from the stairway's midsection. The skeleton had largely decayed, but with it were a jade mask, five spondylus shells, three necklaces/pectorals of round and tubular jade beads, one necklace of shell beads, some with jade incrustations, eight conch shell beads, two sets of jade earflares, two rectangular jade plaques (part of a pectoral), 12 jade disks, 11 obsidian blades, 10 prismatic obsidian cores, and three obsidian blade fragments. The ceramics included two Yaloche polychrome vases—one with diagonal painted lines on the body and a stucco-painted green band on the rim—a plain Molino Black vase, and a Saxche polychrome plate with five cardinally placed painted fish (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999; Figure 14; see also Supplementary Text 4).

Figure 13. Profile of Cormoranes Pyramid showing tomb chambers (CA#) and cist (C) mentioned in the text. Courtesy of INAH.

Figure 14. Cormoranes Room 2 tomb and funerary offerings (partial). See Supplementary Text 4 for full list. Courtesy of INAH / Martinez del Campo (mask).

Below Room 2 was the equally long Room 3, which may have been reentered during the construction of Room 2 and emptied of its contents. A hole in the floor of Room 3 led the excavators into the smaller but intact Room 4. Its male occupant was accompanied by three Herradura Black plates; two Molino Black vases; one Xbanil polychrome vase with cormorant figures; two sets of jade earflares; two necklaces of large and small round jade beads, respectively; three spondylus shells; small shell boxes; two chert eccentrics; a mosaic mask and pectoral of jade and shell tesserae; a set of round and tubular jade bead bracelets; a stingray spine; many other miscellaneous jade ornaments; obsidian blades; and remains of a jaguar pelt (Figure 15, see also Supplementary Text 5).

Figure 15. Cormoranes Room 4. Partial tomb contents including a dancing cormorants polychrome vase and jade mask. See Supplementary Text 5 for a full list. Courtesy of INAH / Martinez del Campo (mask).

Three additional tombs were discovered in 2004 and are believed to be associated with the addition of the front room of the temple and two stairway renovations (Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010a). Two burials were placed in vaulted chambers at the bottom of the stairway, and one was placed in a cist below the front temple room. The cist burial was placed only a few centimeters below the room floor and was much less richly furnished than the other Cormoranes interments. It included a jade mosaic mask and an obsidian blade. Beneath the cist was another empty chamber, bringing the total number of tomb chambers in the Cormoranes Pyramid to seven (Figures 13 and 16).

Figure 16. Cist burial under the floor of Cormoranes temple room. Courtesy of INAH.

Of the lower, plaza-level tombs, Room 6 would seem to be the earlier and slightly more prestigious one due to its position on the pyramid's central axis. In it were the remains of an adult male with signs of healed trauma to the head and limbs. The body was laid on a jaguar pelt with three mosaic jade masks. The chest was covered with hundreds of beads and disks forming a jade pectoral. There were jade bracelets on wrists and ankles. The funerary vessels included three Infierno Black vases, two of them stucco-painted in red and green, featuring a cormorant and a red disk, respectively; the other had a carved geometric design and two polychrome plates, one of them painted with small fish that was almost identical to one found in Room 2. Perhaps the most significant piece was an inscribed bone perforator. The text stated, “it is the bone for blood sacrifice of Yuknoˀm Joˀm(?) Uhut, holy lord of Kaanuˀl” identifying the interred with the Kaanuˀl ruler also known as Sky Witness who may have reigned as kaloˀmteˀ from a.d. 572 to 589, approximately (Velásquez Reference Velásquez and Nalda2004; see also Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024; Figure 17).

Figure 17. Cormoranes Room 6 and selected funerary offering. Bone perforator 3D scan and drawing by INAH/Tokovinine; masks and pectoral photo by INAH / Martinez del Campo; all others by INAH.

Room 5, located just to the north of Room 6, near plaza level, contained an adult male whose furnishings resembled very closely those of the neighboring tomb. He was buried with two mosaic jade masks, jade bracelets, several necklaces/pectorals and, like two of his neighbors, was laid on a wooden bier and a jaguar pelt. The ceramics included two Infierno Black vases, one of which was stucco-painted with a green band on the rim (as a vase in Room 2); two plates of the Infierno Black group, one of them also decorated with a green stucco-painted band on the rim; and two Aguila Orange tripod plates with tubular supports, placing this tomb, as the others, in the early Late Classic ceramic phase (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Cormoranes Room 5 and selected funerary ceramics. Courtesy of INAH.

Although the Lintel Pyramid burial shared a number of features with the ones in the Cormoranes Pyramid—mainly the Infierno Black ceramics, the spacious chamber, and the prestigious location—it differed in the richness of the furnishings. While the Cormoranes burials are accompanied by a remarkable variety of jade and shell ornaments, including masks and jaguar pelts, the Lintel burial has but a few beads (Figure 19; see Supplemental Text 6). The ceramics, however, are indicators of the closeness in time of this tomb and the Cormoranes tombs, if not of the status (Nalda Reference Nalda2003).

Figure 19. Lintel Pyramid burial and funerary offerings. See Supplementary Text 6 for a full list. Photos and drawing courtesy of INAH.

The construction of the pyramids may also have occurred relatively close in time. The Cormoranes may have been the first one to be built, initially, given that at least two earlier construction phases have been documented by excavation, but its final construction phase appears to have occurred after the dedication of Building 6. Therefore, although the first instance of the Cormoranes Pyramid may have been earlier than the Lintel's, the burials so far uncovered within it may actually be slightly later than the one in the Lintel Pyramid (see also Nalda Reference Nalda2003). According to Nalda and Balanzario's (Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010a) assessment, Cormoranes Room 2 might be the slightly later one, Room 6 may be earlier than Room 5, and Room 4 is perhaps the earliest. Uncertainties notwithstanding, using the available chronology provided by texts, stratigraphy, and ceramics, it is possible to attempt a hypothetical correlation of the Dzibanche royal burials with the rulers in the revised dynastic chronology proposed by Tokovinine, Beliaev and colleagues (Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024:Figure 13).

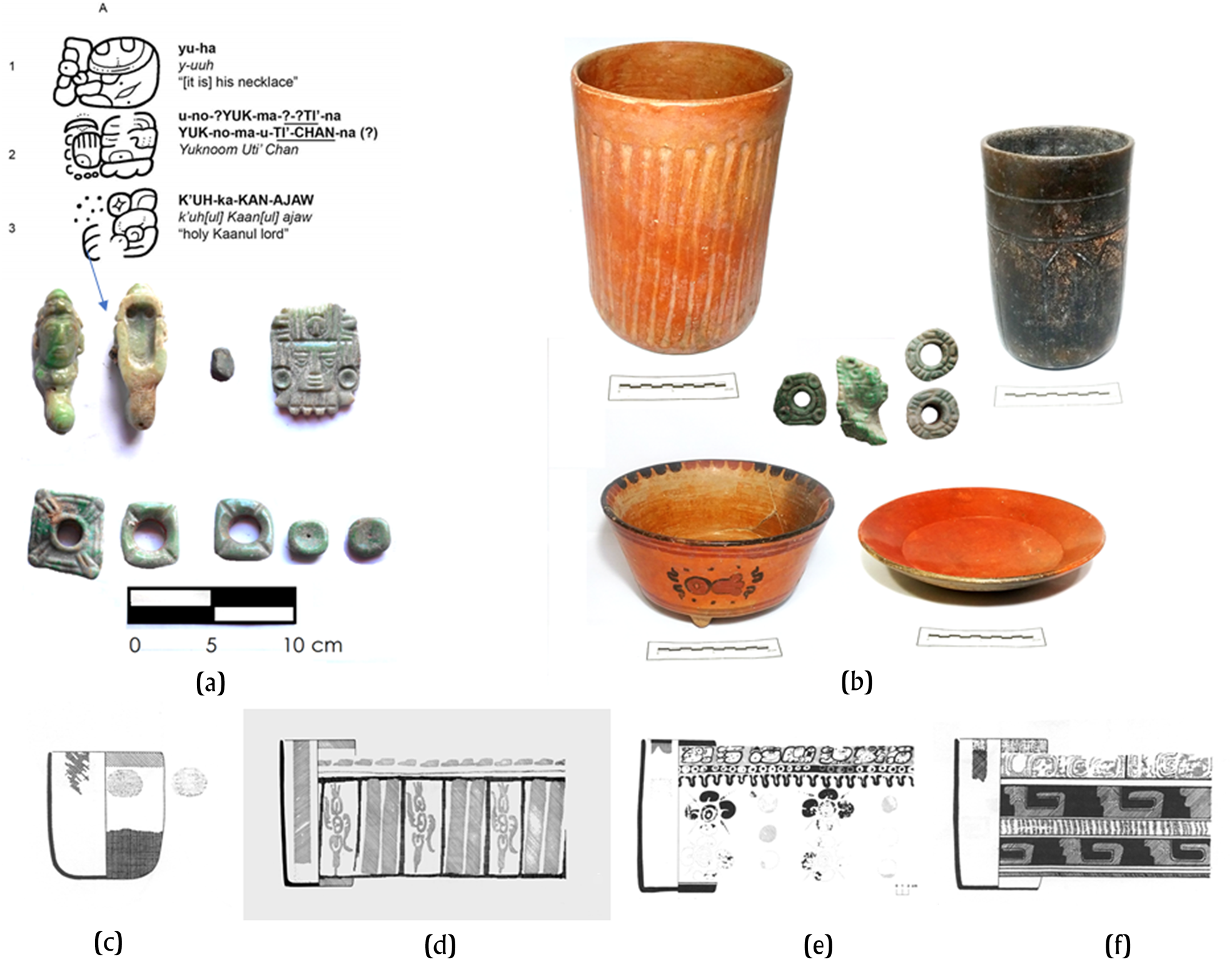

The Building 6 lintel inscription records the accession of a kaloˀmteˀ, presumably K'ahk’ Tiˀ Ch'ich’ (Ruler 16), in a.d. 550 (Martin and Beliaev Reference Martin and Beliaev2017). It is tempting to suggest that the tomb found there may contain the remains of that ruler. The chronology and certain characteristics such as size and axial position of the chamber would support this assumption, but the absence of riches such as jade masks and jaguar pelts do not. Sky Witness acceded as kaloˀmteˀ probably at his death in a.d. 572. As noted earlier, his burial could be the first in the Cormoranes sequence, with Room 5 occurring a short time after it. The ceramics in the Room 5 tomb include several black vases and a bowl with geometric motifs. The ceramics from a royal burial at Holmul are stylistically very similar to the Dzibanche burials. An incised black vase from Holmul is especially reminiscent of the incised bowl in Cormoranes Room 5 and is associated with a jewel inscribed with the name of the next Dzibanche king in line, Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan II, who is otherwise only known from an a.d. 619 reference at Caracol (Figures 18 and 29a–b; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2016:17). Radiocarbon dates and stratigraphy at Holmul place the deposition of the Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan jewel between a.d. 619 and 630. The ceramic similarities would suggest that the individual in Cormoranes Room 5 could be Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan or a ruler who died around a.d. 620–630. The stucco-painted black vases in Rooms 2, 5, and 6 also have strong parallels with vessels found at Caracol, particularly in the tomb in Structure B20-3rd that is associated with an a.d. 537 Long Count date (Figure 20c) and another tomb in Caracol's Toucan Group also dated to the second half of the sixth century (Figure 19d–f; D. Chase and A. Chase Reference Chase and Chase1994:171). Based on these stylistic correlations and associated dates, all six royal interments in the Lintel and Cormoranes Pyramids appear to have occurred in the period of about 60 years, approximately between a.d. 572 and 630.

Figure 20. Funerary objects from Holmul and Caracol with epigraphic and stylistic links to Dzibanche rulers. (a–b) Ceramic and jade offerings from a royal tomb from Holmul ca. a.d. 620–630 (credit: Holmul Archaeological Project); (c) stuccoed and polychrome vases from Caracol tombs in B20-3d from a.d. 537; and (d–f) Toucan Group, ca. a.d.634 ([c] and [f] after D. Chase and A. Chase Reference Chase and Chase1994; [d] and [e] after A. Chase and D. Chase Reference Chase and Chase1987).

Our tentative burial correlation sequence would therefore begin with the burial in the Lintel Pyramid and potentially end with Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan II in Cormoranes Room 5. In that span of time, there are three ruler names known from Dzibanche monuments corresponding to Ruler 18 (i.e., Yax Yopaat/Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan I) and Ruler 19 (i.e., Uk'ay Kaan, “Scroll Serpent”). Then there are the two seventh-century Kaanuˀl names of uncertain chronological placement: “Kaanuˀl lord Yukbil K'inich,” who is mentioned on one of the surviving fragments of Dzibanche's Hieroglyphic Stairway III, and “young (ch'ok) kaloˀmteˀ holy Kaanuˀl lord Ajxisaaj/Ajsaxiij Chan K'inich,” who is mentioned in a parentage statement on a sherd in an offering from the Pom Plaza (see Tokovinine, Beliaev et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024; Velásquez and Balanzario Reference Velasquez and Balanzario2024). Either lord may have died before taking the highest office and have been given a less elaborate burial in the cist. Alternatively, if Rooms 2 and the cist are the later tombs, they may have contained the remains of rulers who immediately succeeded Yuknoˀm Tiˀ Chan II prior to the internal conflict in a.d. 636 (see Helmke and Vepretsky Reference Helmke and Vepretskii2024). This could include Tajoˀm Uk'ab K'ahk’ (a.d. 622–630; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:105) and his successor Waxaklajuˀn Ubaah Kaan, who is known to have been defeated by Yuknoˀm Ch'eˀn II in a.d. 636 and put to death in a.d. 640 (Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2016). The less-than-prestigious cist burial would be commensurate with a ruler who had met such an unfortunate end.

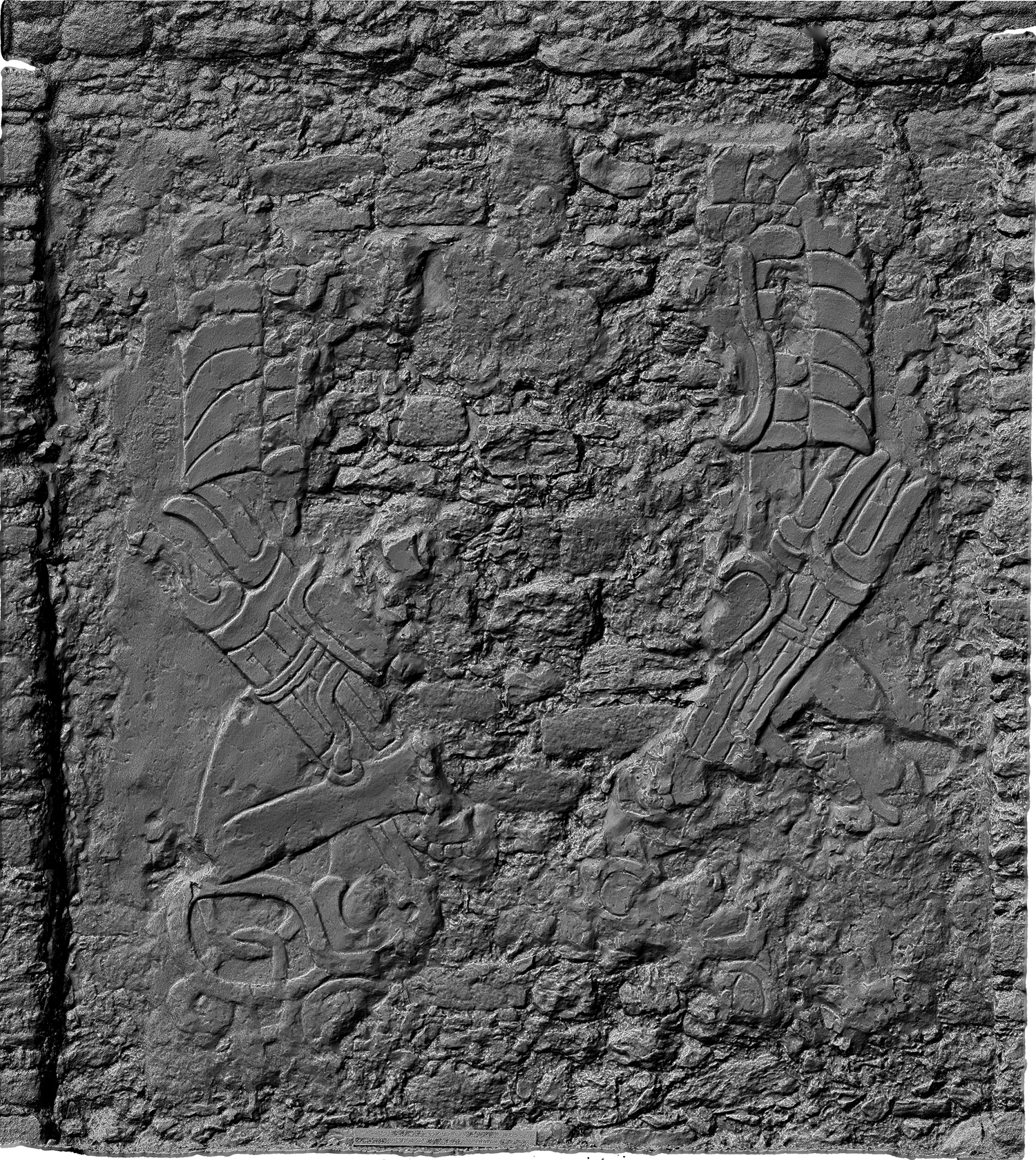

There are two additional burials at Dzibanche from this time that were emptied in the Late Classic period. One is in Tutil Building 2, associated with an extraordinary stucco relief of the Teotihuacan Storm/Puma deity holding torches (Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda, Balanzario, Fournier, Wiesheu and Charlton2007; Tokovinine et al. Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Granados, Khokriakova and Littlejohn2021; Figure 21; see also Velásquez Reference Velásquez and Krieger2011). The relief is evidence of the close association of the Kaanuˀl dynasty with Teotihuacan, as are the reliefs on Cormoranes Pyramid (Figure S1) and the offerings in the early fifth-century burials described earlier. The defacing of the carving also matches desecration in the tomb. Another formal tomb was built under the Kinichna temple, abutting the Early Classic tomb described above and emptied shortly thereafter (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999). Based on interment type and context, both tombs could have contained the remains of Kaanuˀl rulers desecrated during the conflagrations that resulted in the dynasty's installation at Calakmul between a.d. 631 and 636. In sum, the number of potential royal tombs so far uncovered at Dzibanche is 12, all from between approximately a.d. 400 and 630. Of these, only eight contained human remains.

Figure 21. Three-dimensional image from photogrammetry of Tutil 2 wall relief depicting the Teotihuacan Storm/Puma deity holding torches. Image by INAH/Tokovinine.

Concluding remarks

Integrating available archaeological and epigraphic data, we have attempted to present a more detailed, if still preliminary, picture of Dzibanche as the capital of the Kaanuˀl hegemony. Although much work was done by Enrique Nalda's (Reference Nalda and Morlet2000, Reference Nalda2003, Reference Nalda2004; Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2001–2009, Reference Nalda, Balanzario, Fournier, Wiesheu and Charlton2007, Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010a, Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010b; Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999) project, many temples and palaces and the surrounding settlement remain unexcavated. Undoubtedly, much more data will be added in the future. The lidar maps suggest that Dzibanche was perhaps the largest city in the Maya Lowlands of its time—the Early Classic period. Fortunately for us, based on excavation and lidar data analysis, its layout appears to not have been significantly altered in later centuries, enabling us to discern certain patterns of its spatial organization that are possibly linked to its economic, political, and military power.

The land immediately outside the urban zone was partitioned into walled fields. These were the production zones that likely supported the urban population. Settlement zones appear to have been focused on at least one large plaza group, where the local lords probably oversaw land and tribute allocation and ensured the flow of trade and tribute to the central market and royal court. These plaza groups were connected with one another and with the center by a system of causeways to efficiently move trade, tribute, and people.

Dzibanche began to grow exponentially in the Early Classic period, in connection with the many conquests documented on hieroglyphic texts. Thanks to Tokovinine, Beliaev and colleagues’ (Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Balanzario and Khokhriakova2024) new interpretation of the place names on Dzibanche's Hieroglyphic Stairway I, we have confirmation that those initial conquests were directed at nearby neighbors (see also Nalda Reference Nalda2004), such as Sihan Kan, a place name historically linked to Laguna Bacalar, for example, located 37 km to the east, beyond what we may therefore infer was the limit of the Dzibanche hinterland up to then. Rulers at El Resbalón (15 km) and Pol Box (12 km), the two nearest royal centers to Dzibanche, expressed their subordination to Kaanuˀl's Sky Witness (Carrasco and Boucher Reference Carrasco and Boucher1987; Esparza and Perez Reference Esparza and Perez2010). Given their proximity, they may have been assimilated even earlier, as probably were Nicolás Bravo and González Ortega, judging also from the clear architectural similarities to Dzibanche. Further afield, Kohunlich (37 km) and Noh Kah (60 km) had strong architectural and funerary similarities with Dzibanche in the Early Classic period as well (Lopez et al. Reference Lopez, Villegas, Torres Diaz and Walker2016; Nalda Reference Nalda2003; Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2010a; Figure 3)

At Dzibanche, the early period of greatness is well represented by the majestic architecture of the Kinichna complex and by the royal tomb within it, together with the Buho Pyramid and tomb (ca. a.d. 400). This was a time of very strong ties with Teotihuacan, which we suspect may have had a role in Kaanuˀl's military success, as it did with Tikal's.

The burials of the immediate successors of these early rulers are unrepresented in the current sample. One Late Classic jade mosaic mask possibly pertaining to an unknown seventh-century ruler was placed in a cache on the steps of the Buho Pyramid together with a Saxche polychrome plate (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999:32; see also Figure S2). Fortunately, however, recovered texts help us place—with varied degrees of confidence—two rulers at Dzibanche: K'ahk’ Tiˀ Ch'ich’, the first known to hold the title of kaloˀmteˀ, and his successor, Yuknoˀm Hoˀm(?) Uhut Chan (Sky Witness), whose apparent overlap between a.d. 561 and 572 confirms a form of two-tiered corulership at Dzibanche that solves the important issue related to the dates of accession in the dynastic vases’ king list vis-à-vis the epigraphic record (Martin Reference Martin2017).

The other burials recovered in the Cormoranes Pyramid by Enrique Nalda's (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and López1999) project may include most if not all of the remaining rulers until the dynastic turmoil of a.d. 636 and the dynasty's installation at Calakmul. It is noteworthy that no royal burials from the period following that conflict have been found so far, although many potential locations remain unexcavated. Based on later texts, Velásquez and Balanzario (Reference Velasquez and Balanzario2024) note, however, that the Kaanuˀl power did not end at Dzibanche but continued to be exercised by its k'uhul ajaw through the Terminal Classic period. The manner in which the Kaanuˀl titles may have been contemporaneously kept by royal courts at Calakmul and Dzibanche still remains obscure. What is certain, however, is that Dzibanche's temples continued to inspire awe in Maya people long after its kings had vanished.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536122000207.

Supplementary text 1. justification for Kaanuˀl spelling.

Supplementary text 2. List of artifacts in Kinichna tomb 102.

Supplementary text 3. List of artifacts in Buho Pyramid tomb.

Supplementary text 4. List of artifacts in Room 2, Cormoranes Pyramid.

Supplementary text 5. List of artifacts in Room 4, Cormoranes Pyramid.

Supplementary text 6. Lust of artifacts in Room 601, Lintel Pyramid.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to INAH’s Consejo de Arqueología and the Centro INAH Quintana Roo for authorizing and supporting the various research projects summarized in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.