Many societies use dress to signal different social identities. Several overall studies of Maya dress have tried to connect dress to social identities, especially after identifying glyphic titles, but have produced few specific suggestions tied to how they dressed. The research reported here presents a model of the relationship among certain Maya titles and elements of dress, specifically headgear.

The Late Classic Maya polities varied in size, but most were governed by a hereditary nobility led by a sacred ruler—a k'uhul ajaw, or Holy Lord. It is likely that a Maya court contained nobles and other important people who helped manage the polity. Epigraphers have identified many titles, and Mayanists infer that those with titles played some role administering their polity and consider them as part of the Maya court (Inomata Reference Inomata, Inomata and Houston2001; Jackson Reference Jackson2009). How similar the Classic courts were to the ethnohistorical administrative systems of Yucatan and the Highlands is unknown. As we will see, if my model is correct, those with certain titles appear often in court scenes, and we should consider them as members of the Maya court.

Scholars have addressed titles, specifically exploring their relationship to the structure of the Mayan court (Coe and Kerr Reference Coe and Kerr1998; Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009:168–176; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Jackson and Stuart Reference Jackson and Stuart2001; Zender Reference Zender2004). So far, epigraphers have identified two groups of titles for court personnel. Seated titles are those for individuals such as rulers who undergo a ceremony, called a “seating” (Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Stuart Reference Stuart1996), and are formally invested in their title. The second group consists of those for which we have no evidence for such seating.

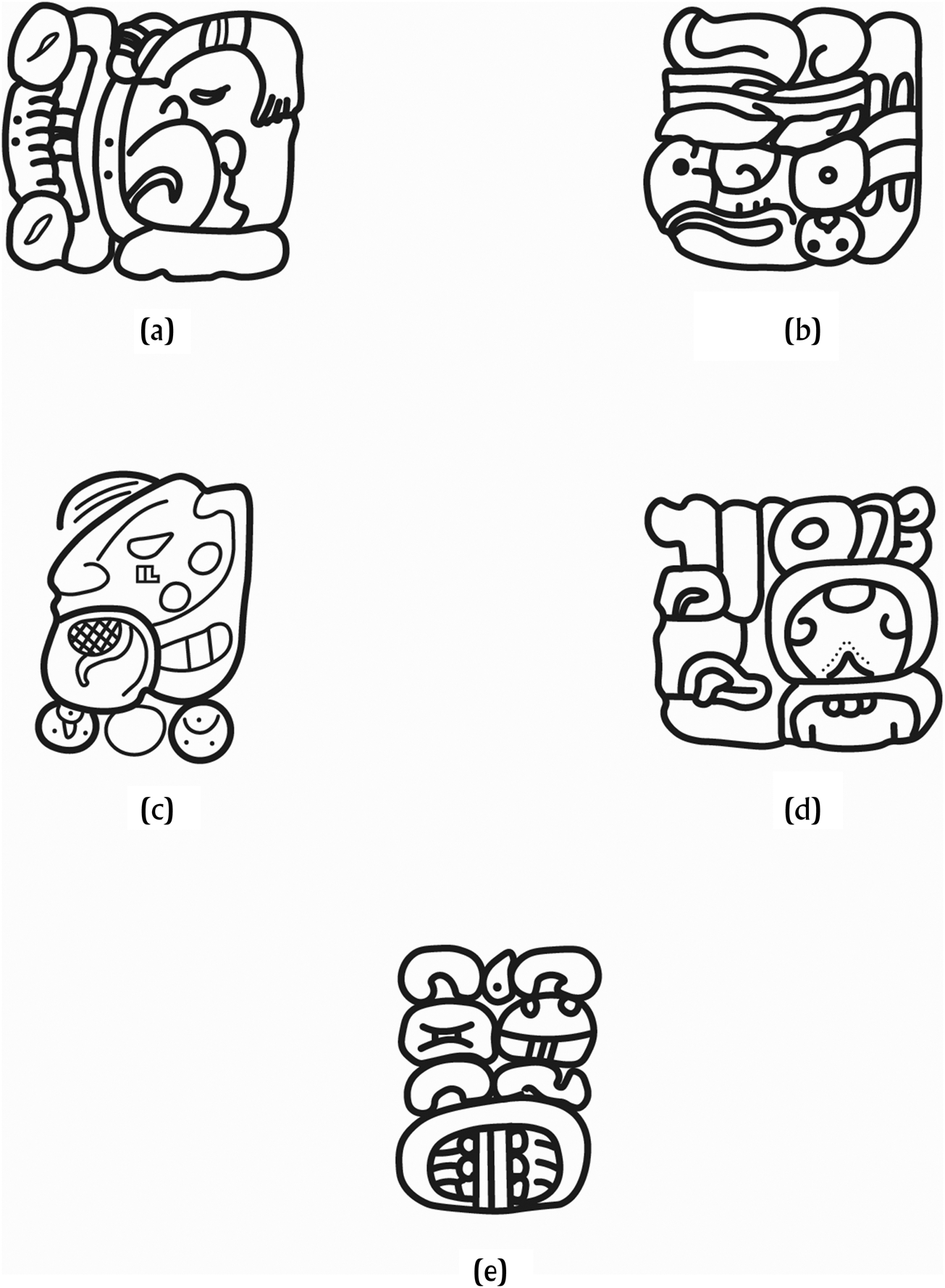

The formally seated titles most often addressed are aj k'uhuun, banded bird (see Bíró et al. Reference Bíró, MacLeod and Grofe2020 for recent translation), sajal, ti'sakhuun, and yajaw k'ahk’ (Figure 1). The second group, without “seating” evidence, includes titles such as lakam (Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009; Stuart Reference Stuart1996) and bahte’ (Houston Reference Houston2008), or those associated with scribes (tz'ihb) or “wise one” (itz'at) (Stuart Reference Stuart1987, Reference Stuart and Kerr1989). These could be occupations (Bíró Reference Bíró2011:292). The anahb title is undeciphered (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:66, n.1) and was “connected to courtly service in ways not yet understood” (Houston Reference Houston2018:151). The term ba (head) was applied to both groups of titles; but those of the second group (such as baah pakal, “head shield”) were achieved or appointed roles (see Graña-Behrens et al. Reference Graña-Behrens, Megged, Wood, Wood and Megged2012). However, some titles of the second group, such as lakam, may have been inherited in local lineages (Tsukamoto and Esparza Reference Tsukamoto, Esparza Olguín, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015:39).

Figure 1. Maya seated titles: (a) ajk'uhuun; (b) banded bird; (c) sajal; (d) ti'sakhuun; (e) yajaw k'ahk’. Drawing by and courtesy of Péter Bíró.

We are beginning to understand how people with seated titles received their titles and what they did in the court. For example, at Palenque, the banded bird titles were inherited within a lineage associated with the royal lineage (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b). Sajal and aj k'uhuun can also be inherited. At Copan, however, each new ruler appointed their own ajk'uhuun (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:27–28)—at least at the end of the Late Classic period. They probably included members of the royal family as well as nonroyal nobles.

We have limited knowledge of the roles titled individuals played in the political-religious organization of the court and polity. Several studies tried to identify a title's function in society by translating and unpacking the meaning of the Maya words. Jackson (Reference Jackson2013) traced the available life histories of title holders. More general approaches to the Maya court include, most notably, the two-volume work by Inomata and Houston (Reference Inomata, Houston, Inomata and Houston2001a, Reference Inomata, Houston, Inomata and Houston2001b). Other studies have discussed the court and its nobles from a comparative perspective and summarized what was known about them and their behavior (Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009; Jackson Reference Jackson2009).

Although the Maya in the Late Classic period often tagged individuals with their titles in both sculptural and ceramic media, they did not do it consistently. If we could identify titled positions by dress, it could help us understand more about the relationships among the different titles and the workings of the Late Classic Maya court.

In this article, after discussing methods and dress, I present a model of how the Late Classic Maya used certain headgear to signal their titles, and then I suggest that they used embellishments to signal other social markers, probably events and activities. I identify two groups of headgear: Standard and Special. Headgear in the Standard group have a specific standardized construction process and form. I call these “hats” to distinguish them from the Special headgear. The Special group consists of a wide variety of forms and construction processes, little of which is regularized. Then, I show that Standard hats are found throughout the Maya Lowlands, except in a few areas with limited pictorial evidence. I show that four titles can be linked to Standard hats. Using social space on the vases, I identify a hierarchy among the different titles by the frequency of their relative positions in the narrative scenes on vases. As discussed below, the model does not account for all examples because we do not understand all the contexts that are depicted, or all the rules associated with dress.

Methods

I use scenes that I and others consider to be depictions of historical narratives. However, although narrative scenes depict events, they are not photographs, and they likely depict an idealized representation of what court life should look like (Jackson Reference Jackson2009:73; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet, Inomata and Houston2001:223).

Previous approaches have not focused on the study of nonroyal, nonritual dress, despite the various attempts to identify status and rank and social positions (Clarkson Reference Clarkson and Sidrys1978, Reference Clarkson1979; Taylor Reference Taylor1983; Tremain Reference Tremain2017). Most combined all media (except Tremain, who used just ceramics), which lumped ritual dress with everything else. Browder's (Reference Browder1991) descriptive inventory used just sculpture. Parmington's work (Reference Parmington2003) used only sculpture and only ritual settings to identify clothing specific to sajalob. He concluded he could not differentiate between the clothing of rulers and sajals except in terms of elaborateness. Because he was using only ritual contexts, this conclusion is restricted to those ritual contexts. Recent work on Maya dress does not attempt to identify social positions but does include all media and all contexts and time periods (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Houston and Rossi2020). The primary focus of these recent articles is on royal dress, and they make interesting contributions, especially by examining materials and construction of dress. Attention to nonroyal dress is limited. Nonroyal “simpler headdresses” (headgear) worn by courtiers are treated in one paragraph in the two articles dealing with headgear and headbands (Carter and De Carteret Reference Carter, De Carteret, Carter, Houston and Rossi2020; Rossi et al. Reference Rossi, Lukach, Dobereiner, Carter, Houston and Rossi2020).

Previous approaches have also used modern interpretations of scenes to group them into categories and describe the dress in those categories. Starting with interpretive contexts instead of first defining the dress elements can lead to confusion. You cannot extrapolate from what musicians are wearing in one context to other contexts, in which the rules of dress may be different. It is best to identify dress elements and then see if they occur in a pattern that could inform on past behavior.

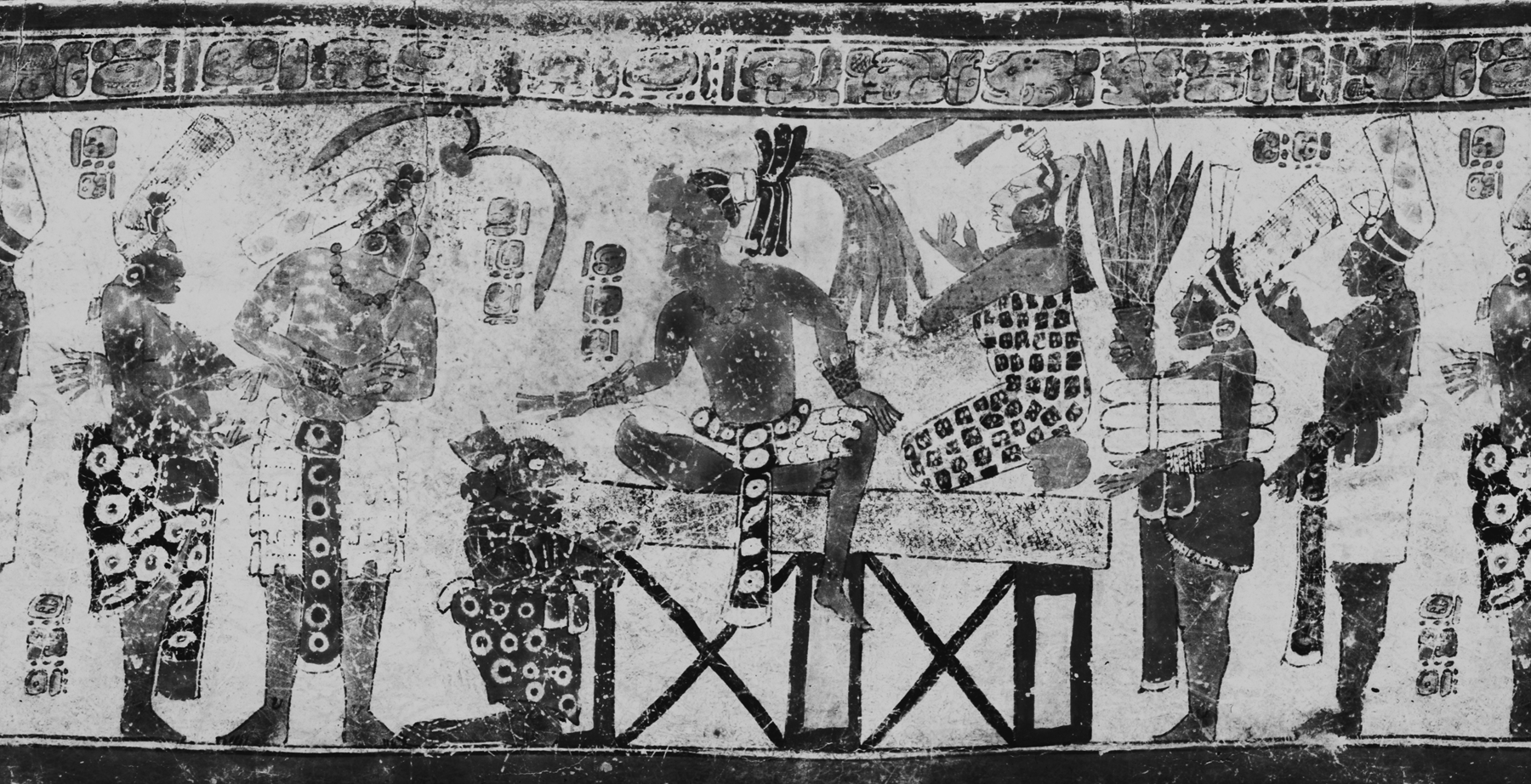

This article comes from a larger study of Maya male courtier dress in historical scenes (Cheek Reference Cheek2020). Repeatable types of headgear occurred in different combinations in vase scenes. This suggested they had social meaning, as opposed to other clothing elements such as waist clothing that had little regularized differentiation from person to person in a scene. Waist clothing may be a quasi-uniform (Tremain Reference Tremain2017:75–76): an item worn by all in a group representing solidarity of the group with some individual variation—in this case, elite dress. Waist clothing had six basic elements: loin cloth, loin cloth apron (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950), cummerbund (Greene Robertson Reference Greene Robertson1983), hip cloth (Anawalt Reference Anawalt1981), belt, and sash. Sometimes, men wear just the loincloth, and the cummerbund and sash seem optional or context specific. The Standard headgear is simpler, with three basic elements: the basic hat form: a cone, net, or tube; a pointed support cloth; and a hat tie (Figure 2). The latter two hold the hat on the head. Headgear in general, especially the Standard hats, often have additions and attachments.

Figure 2. Vessel K4030 showing Standard hats. From the left: Net Forward hat, Wrapped Backward hat, dog imitator, prime figure with Special Tied Hair and a Flower Circlet, Woman with hair pulled through jade spool, Net hat, Wrapped Forward hat. Note the pointed material supports at the base hat form. Photo by Justin Kerr. Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

Commemoration and audience

The implications of commemoration and audience, two important concepts in analyzing vases, have not been explored. Both vases and stelae commemorate specific but different important events. Narrative vases do not show contact with supernaturals or regulation of the spiritual welfare of the community, such as stelae (Stuart Reference Stuart1996, Reference Stuart and Scarborough2005a), but rather interactions among the ruling elite. For this reason, they should be intelligible to their target audience: other elites.

Rice (Reference Rice2009:145) has summarized the value of the vases for memory creation through commemoration: “The painted scenes materialize social memories of the political events that created or commemorated the statuses of the recipients, events that often occurred at critical junctions of time.” She points out that these vases “were highly visible mechanisms strategically deployed to sustain geopolitical power and identities and reinforce divine status” (Rice Reference Rice2009:145; see also Halperin and Foias Reference Halperin and Foias2010:393–395).

For painted scenes to be effective in “memorializing social memories” they must be understandable to their audience, who are Maya elites both in their own polity and in others. The intended audience places constraints on two groups: the makers (broadly conceived) and the patrons (see Schiffer and Skibo Reference Schiffer and Skibo1997:42–43).

The makers (both the patrons and the artisans) of vases that memorialize events had to know the intended audience to allow that audience to understand a scene. If an audience cannot understand a scene, it becomes a preciosity with a limited meaning. Other elite should be able to identify the social positions and status of the participants in the scenes. Dress and the position of the individuals in a scene can provide this information, and they have done so in many cultures. Standard elements, even if idealized, help increase understanding even if the details are not exactly as they happened, and they enhance the visual performance of the narratives as communication.

I addressed position in social space by dividing the elite participants into the prime (the main figure facing forward, looking to his right), the opposing figure, and the attendees. Dividing the spatial positioning this way fits well with Bíró's (Reference Bíró2007) observations on elite interaction and identity. He argues, “Texts are none other than documentation of special roles in rituals, and most elite persons had a well-defined position to each other according to participation and presence” (Bíró Reference Bíró2007:99–100). He proposes that the Late Classic language had five morphemes that “expressed joint action.” The morphemes e(b’)tej and *kab'i were connected to the main actor performing the action. The secondary actor who may have been performing the same action was connected to the action by *itaa. The meaning of *ila is “people who were passively present witnessing” or just “present.” The fifth morpheme is *ichnal, a word that means “witnessing” in the sense of authorization (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:173–175). According to Bíró, “Classic Period politics was a constant struggle to be connected to these expressions, or better said to be in a position where status is recognized by participating in rituals and events where position in a text was formed around these five words” (Reference Bíró2007:100). Bíró's interpretation implies that “text” of the commemorative vases documents the social position of individuals in the courts who are the intended audience. Jackson makes a similar observation about position reinforcing “messages about roles within the court” (Jackson Reference Jackson2009:73–76; 82).

The intended audience was also critical to the makers, including potters, drafters, and scribes. In many cases, these were the elites themselves (Inomata Reference Inomata, Hruby and Flad2007; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet, Costin and Wright1998). Those doing the drawing had to understand the features of court life to depict it accurately. In general, artisans wanted their audience to be impressed with their work as a prestige object that had “technical and aesthetic sophistication” (Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet, Costin and Wright1998:85). For a narrative scene, it had to depict court life well enough for it to be understood as commemorating an event. Vessels that showed uncommon activities would have had a limited audience or would have been unintelligible.

Together, the constraints of the intended purpose of the vase as narrative commemoration and the intended audience made it necessary for a vase to depict at least an idealized version of an event in court life. If the structure of court life differed substantially from polity to polity, vases would not have had much social currency other than being admired as pretty curiosities. Consequently, if court life had a standardized structure of elite culture, it should be identifiable on a vase. Dress, as well as positioning, was key to communicating elite culture.

Dress

Anthropologists today define dress as “an assemblage of body modifications and/or supplements” (Roach-Higgins and Eicher Reference Roach-Higgins and Eicher1992). This includes any visible way of decorating the body, which includes body modifications (scarification, head deformation, hairstyles, body paint) and supplements (sashes, headgear, jewelry). People use clothing and other kinds of bodily adornment to communicate a variety of cultural and social information, such as identities, values, and origins (Kuper Reference Kuper1973:365; Pancake Reference Pancake, Shevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991; Schneider Reference Schneider1987:412).

Modern anthropological study views dress as “created through agency, practice and performance” (Hansen Reference Hansen2004:370; see Orr and Looper Reference Orr, Looper, Orr and Looper2014 for a similar discussion of trends in dress studies). In the past, Maya “clothing received only passing attention” and made clothing “an accessory in symbolic, structural, or semiotic explanations” (Hansen Reference Hansen2004:369–370).

Dress and its elements, as objects, provide information about activities and interactions with people (Schiffer and MillerReference Schiffer and Miller1999). They can also affect how people interact with them (Robb Reference Robb, Overholtzer and Robin2015). Scholars have called people's ability to understand the message of a scene its visual performance (Schiffer Reference Schiffer2016:90). Artists could use elements such as sign language (Ancona-ha et al. Reference Ancona-ha, De Lara, Van Stone and Kerr2000; Miller Reference Miller1983), various material objects, and even text to clarify the message.

I consider dress as a compound artifact that interacts with an individual to produce cultural conventions through daily actions. A behavioral chain perspective (Schiffer Reference Schiffer2016; Skibo Reference Skibo2009; Skibo and Schiffer Reference Skibo and Schiffer2009) enables us to consider dress items as artifacts rather than just as items that illustrate a particular topic. This approach focuses our attention on how the Maya constructed an ensemble and helps identify the details of production and consumption (Dietler and Herbich Reference Dietler, Herbich and Stark1998:241, 245–248). These are important because the artisans make decisions, called “technical choices,” in response to anticipated interactions along the behavioral chain such as visual performance. The decisions lead to an object's formal qualities and contribute to performance characteristics (Skibo and Schiffer Reference Skibo and Schiffer2009:12–15). Objects like dress have visual performance characteristics by which people, such as the intended audience, judge whether they are useful for their purposes. Depictions of standardized dress are important for conveying information about participants and activities in narrative scenes. We should also not forget that standardized dress would create a sense of group identity among the elite and help to reinforce interelite cohesion.

My underlying strategy is to focus on repeated practices (Joyce and Lopiparo Reference Joyce and Lopiparo2005) of daily dress. Dressing creates and recreates the role one is to play or the person one intends to be that day. Through repetition, these practices gain symbolic and social meaning that supports the social structure and makes the body the site of social identity (Dant Reference Dant2004:26; Eicher Reference Eicher and Eicher1995; Orr and Looper Reference Orr, Looper, Orr and Looper2014:xxiv; Roach-Higgins and Eicher Reference Roach-Higgins and Eicher1992:5; Wynne-Jones Reference Wynne-Jones2007). I concentrate on one segment of the actions involving dress—the acts of dressing and use. If a standard male courtier dress ensemble existed, we should be able to identify a set of practices—the interactions with material culture—that control its construction.

I have found that it is useful to define dress medium by medium—that is, initially focus only on vessels and then look at sculpture, murals, and figurines separately. Each medium has different audiences, and its makers manipulate what it displays to satisfy the communication needs of its audience.

The vases

The greatest amount of material for examining court structure comes from Late Classic vases with narrative scenes because they show court activities with human interaction. Most of these are polychrome, and they came from the digital Kerr Maya Vase Database (https://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya.html; the Ks before a vase number refers to this database).

Most vases used in this study were looted, and therefore lack provenence. This makes it hard to explore whether Late Classic vases depict local or regional dress. Reents-Budet and Bishop (Reference Reents-Budet, Bishop and Zelst2003; Reents-Budet et al. Reference Reents-Budet, Bishop, MacLeod and Reents-Budet1994; Reents-Budet et al. Reference Reents-Budet, Bishop, Taschek and Ball2000) attempt to correct this lack through the Maya Ceramics Project. However, not enough of my sample overlaps theirs to address regional issues. I added a few excavated vases with provenence. These include vases from Tikal (Culbert Reference Culbert1993), Tayasal (Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Boone1985), Caracol (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Inomata and Houston2001), Tamarindito (Valdés Reference Valdés1997), Motul de San José (Halperin and Foias Reference Halperin and Foias2010), and the La Ruta Maya Vase (Luin et al. Reference Luin, Tokovinine, Beliaev, Arroyo, Méndez and Aragón2015). I also added a few from museum collections. All contained scenes with Standard headgear.

The sample included 138 vases. The vases had 168 scenes with 645 figures and an average of about four figures per scene. Twenty-seven of the interactors on 18 vessels had some unclassifiable hats due to surface damage. I included them in the study given that they are only 4.2 percent of the figures, and their exclusion would have affected the interaction analyses. I was interested in interaction between individuals, so there was usually a prime and an opposing figure, or two groups facing each other. Most activity took place within a court setting.

I chose scenes that had Standard hats and, for the most part, at least two interacting opposing people. Many vases showed court scenes identified by the presence of a bench, throne, steps, or drapes. I excluded vases that contained mythical and warlike (except when warriors were in court) scenes because they may show rules for dress that differed from those for court. Mythical scenes could be identified because they contained well-known supernatural and mythical figures such as Chaks; Gods N, L, Hun and Hunapuh; the Moon Goddess; the Maize God; and figures with god markings, as well as other defined mythological creatures such as deer and snakes. I did not include vases that the Kerr database noted were altered heavily.

I excluded most scenes showing the following:

• Dances, given that participants wore special ritual dress

• Human sacrifice or ball courts

• Individuals that Coggins (Reference Coggins1975) called “sitting lords”: vessels having solitary individuals in separate panels. Many of these seemed to be supernaturals.

Headgear

I divided the headgear (everything covering the head) into two groups: Special and Standard (Table 1). Special headgear was much more varied and included headdresses, hairstyles, and other minor types of headgear. I use the term “headdress” for headgear that is like the ornate constructions worn on stone monuments by rulers. Prime individuals often wore headdresses. The Standard group consisted of hats; hats were less complex than headdresses, and their construction was simpler and repetitive. Hats made up 56 percent of individual headgear, and at least one appeared on 73 percent of the scenes. The courtiers wore Standard hats in everyday court life. People in all three vase positions (primes, opposing, and attendees) wore Standard hats. Courtiers wore hats during court events. Headgear also had embellishments: things added to the base hat type.

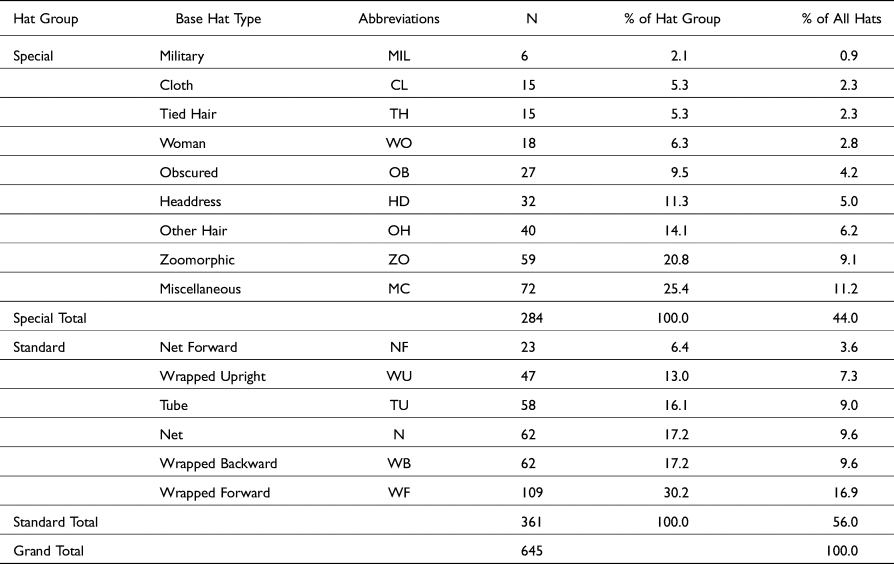

Table 1. Headgear type by hat group and all hats.

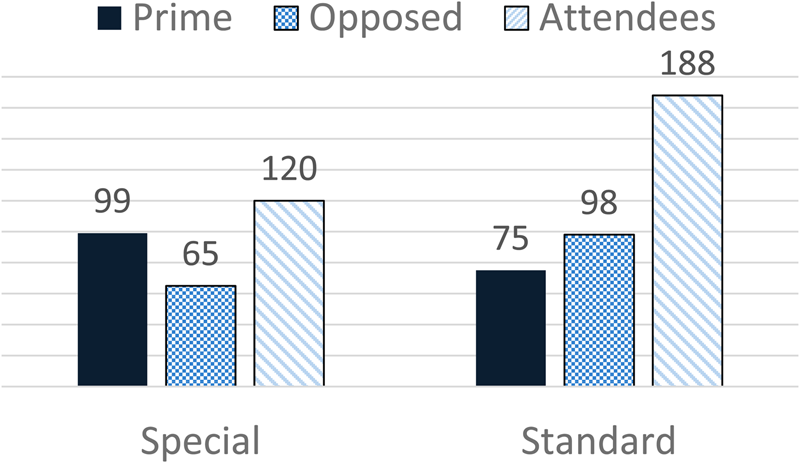

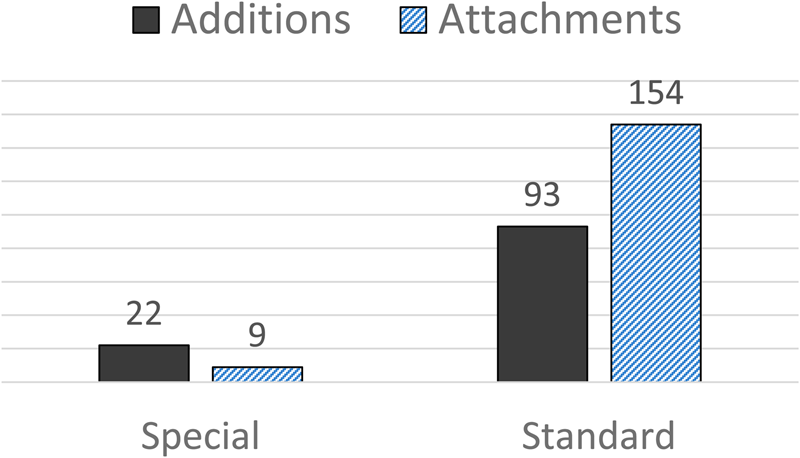

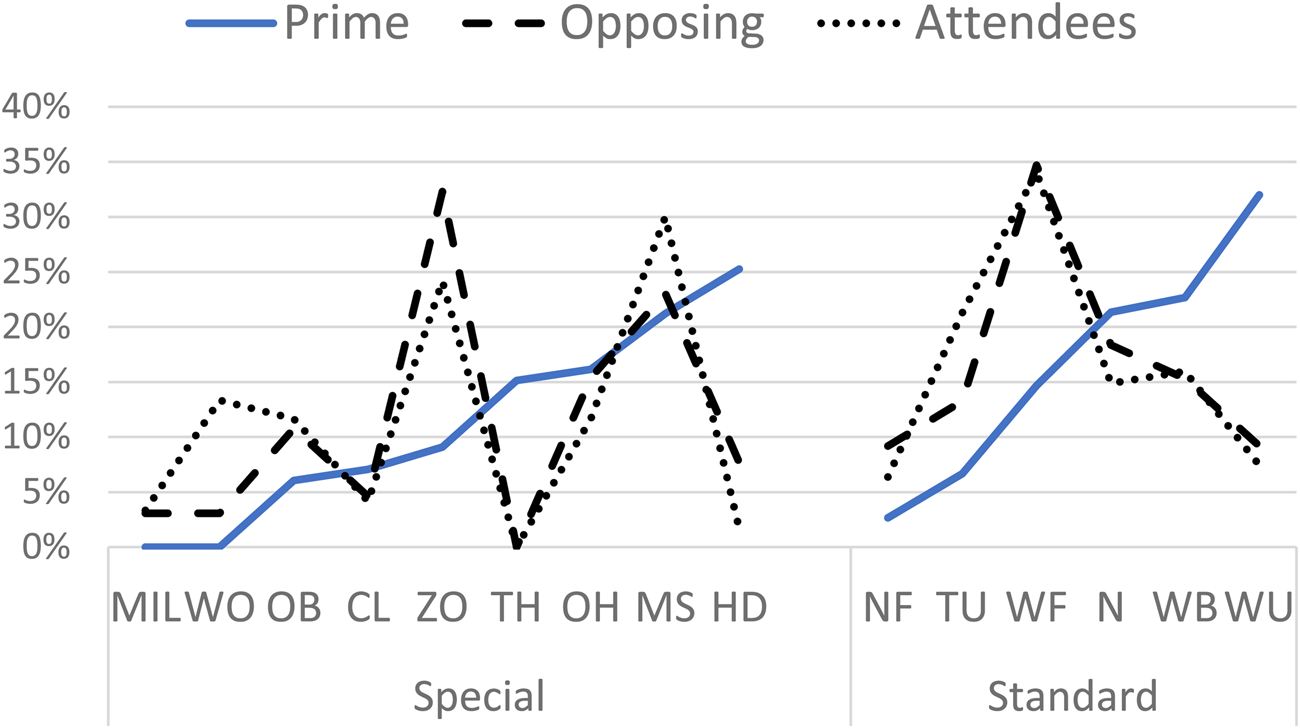

If there were no difference in headgear in each position, then the two groups of hats should be randomly distributed over the different positions. If they are not distributed this way, then the two variables, the positions, and the hat groups have a relationship that is not random. The chi-square test of independence evaluates the existence of this relationship. Figure 3 shows that a relationship exists between position and headgear worn, and that it is significant. Standard hats were on fewer primes than Special hats, even though Standard hats were more common. Also, standard hats were more abundant—sometimes substantially so—in the other two positions. People sporting embellishments wore Standard hats much more often than did people sporting Special hats (Figure 4). Both analyses are significant statistically and visually, and they showed that the two groups were worn by people playing substantially different roles in court life.

Figure 3. Count of vase positions in visual space of Special and Standard headgear groups (chi-square p-value: 0.003).

Figure 4. Count of embellishments on headgear groups (chi-square p-value: 0.001).

Standard headgear

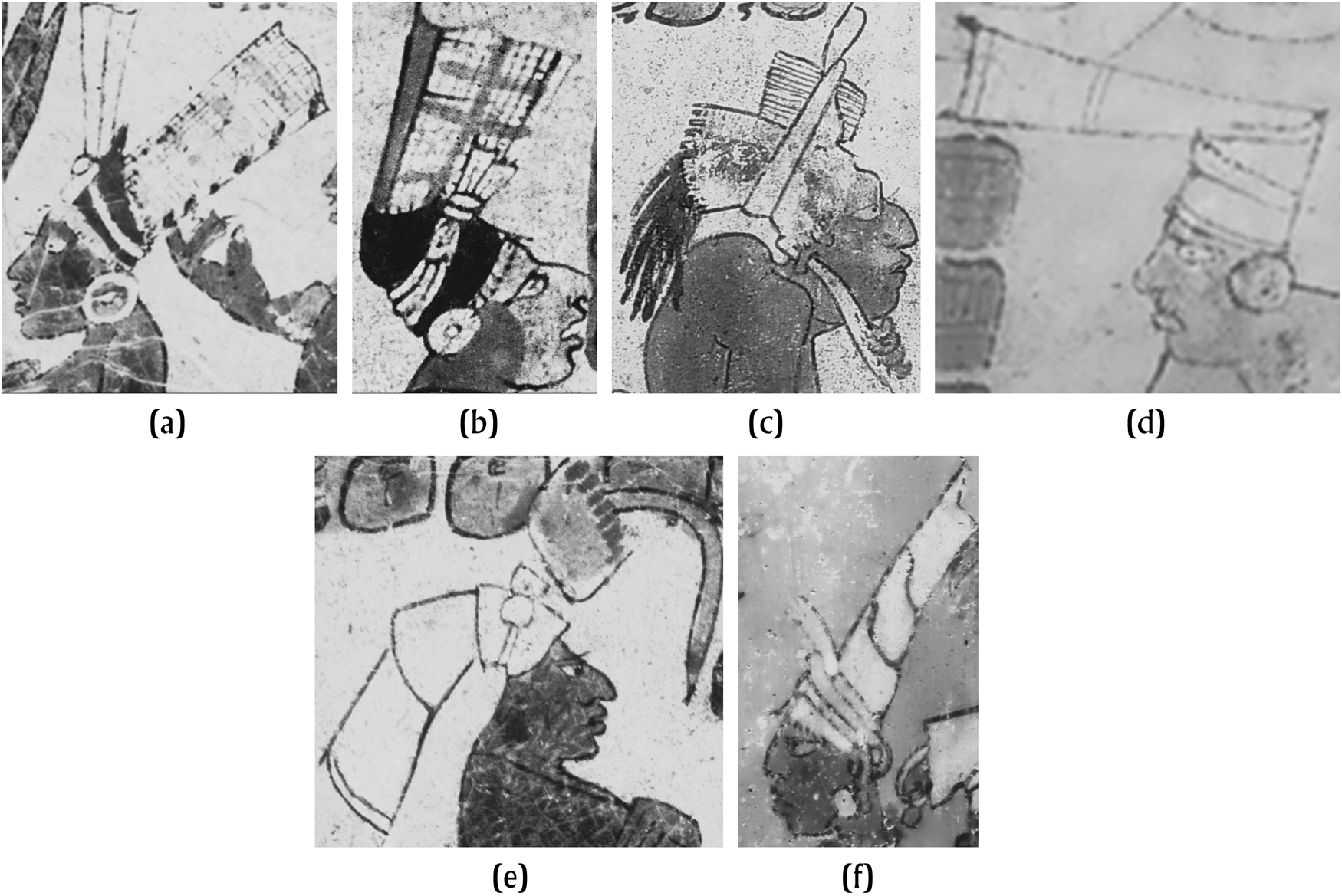

I identified six hat types that appeared consistently on courtiers (Figure 5). All were constructed as a cone of cloth, paper, or net (Table 2). The six were Wrapped Upright (WU), Wrapped Backward (WB), Wrapped Forward (WF), Tube (TU), Net (N), and Net Forward (NF).

Figure 5. Standard hat types: (a) Net hat K4030; (b) Net Forward hat K7999; (c) Tube hat K1453; (d) Wrapped Forward hat K2732; (e) Wrapped Backward hat 8818; (f) Wrapped Upright hat K5738. Photo by Justin Kerr. Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

Table 2. Attributes of Standard hats.

1 A variation, often seen on dwarves, has a short vertical section before a sharp forward bend.

2 Stiffened cloth-and-clay mask at Aguateca suggests that cloth could have been used (Beaubien 2002).

3 Some versions are drawn as short with red net without the dark strip. Others had painted fret decorations.

4 Strip of material with a peak that ties around the base hat that helps support the direction in which the base points.

5 Cloth that ties the support and base to the head. It is often longer than necessary and usually on the side of the head.

The wrapped hats (Figures 5d–f) were those Coe called “wrapped napkin hats” (Coe Reference Coe, Inomata and Houston2001:275–276; Coe and Kerr Reference Coe and Kerr1998:106). Various people have referred to these as “wrapped” in a general sense, including Reents-Budet (Reference Reents-Budet1994:76, 136), and I use the term because that is the way they are constructed. Spanish commentators reported that Maya priests wore tall conical hats made of bark paper (Zender Reference Zender2004:105–106) or other material, such as the Wrapped Upright type of hat. Previously, all the Wrapped hats in whichever direction they pointed were considered as one type (see Zender Reference Zender2004, among others), but this seems unlikely. All varieties can appear together on the same pots, implying that the artist saw them as having different meanings.

I changed what Coe called a “headwrap” to a Tube hat (Figure 5c) because it is more descriptive of its structure. It was the only Standard hat seen on both men and women. The Net Forward hat could just be a variant of the Net, but I consider it a separate type because the wrapped hat types used the cone position to imbue social meaning (Figure 5a–b).

Hair rarely appears except on the TU hat (Figure 5c). The hidden hair in the other hats may have been a sumptuary requirement in court. In contrast, the primes often had exposed hair. A few vases have people with hair coming out of the back of another Standard hat type (K1563, K1790, K3463, K6984, K7020, K8089, K8469, La Ruta Maya).

Special headgear

Limited space prevents describing the Special headgear in much detail (Table 1). Headdresses were ornate and built on a wooden framework (Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986:67). When warriors, carrying weapons, appeared in court, they wore headgear like that identified by Hellmuth (Reference Hellmuth1996) as military headgear. Zoomorphic headgear included various kinds of animals and birds plus composite creatures. The cloth category includes various unique creations, such as turbans or complex head wraps. Women's headgear, except in one case of a Standard hat, consisted of hairstyles. The obscure category included headgear that was unidentifiable because of deterioration of the painting. Anything other than the two hair categories were placed in the miscellaneous category.

Tied Hair (TH) hair was long and not enclosed in a hat. Instead, it was tied with a series of cloth bands. It projected over the forehead of the individual and was only worn by primes. It is possible that a ruler wore it like this when he was impersonating Chahk, whose hair is often shown this way.

Other Hair (OH) types are all other hairstyles besides TH. I noted only one OH like those at Palenque. A lock of hair was pulled through a jade flower or disk on the forehead (K787, K1445, K5858). On vases, only prime individuals are shown with this style. Greene Robertson (Reference Greene Robertson, Robertson and Benson1985:Type S10) assumed from contexts that this style was restricted to the royal family (for a discussion of hairstyles and color, see Greene Robertson Reference Greene Robertson, Robertson and Benson1985 and Miller Reference Miller, Lozada and Tiesler2018).

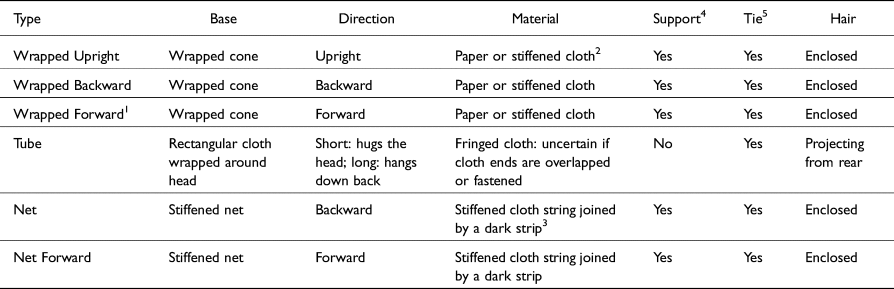

Embellishments

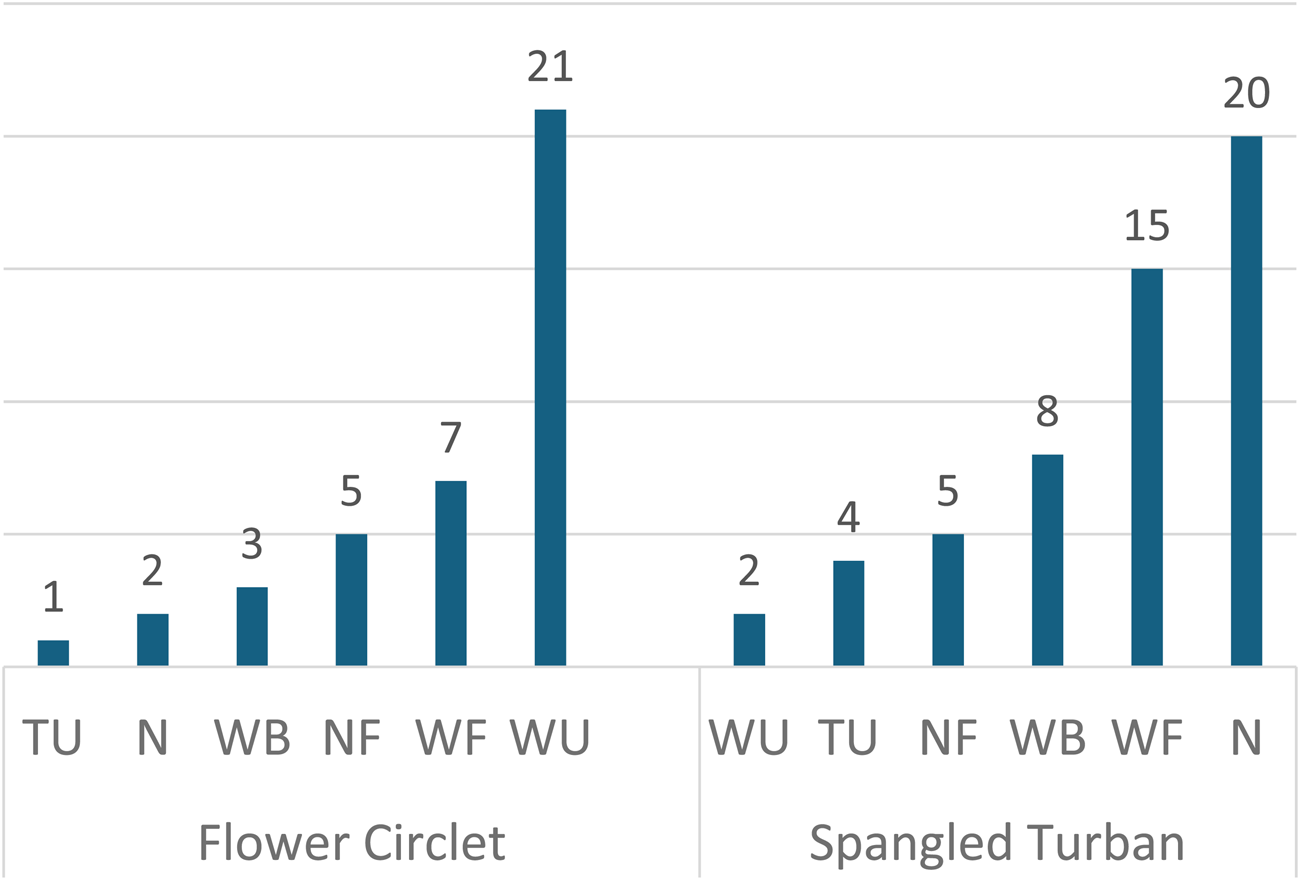

Embellishments included additions and attachments (Figure 6). Neither class can be addressed fully because of space limitations. Like the basic headgear types, they appear in different frequencies on Special and Standard hats (Figure 4). They are important because they affect the performance characteristics of the basic headgear types. The two additions, a Flower Circlet (FC) (Figure 6a) and a Spangled Turban (SP) (Figure 6b), do not identify separate Standard or Special hats. They are just added over the basic hat types. It is likely they signal different events a courtier was participating in or overseeing.

Figure 6. Additions and Attachments : (a) Flower Circlet K8469; (b) Spangled Turban K956; (c) stick bundle K6494; (d) brushes K3009; (e) hook K3009. Photo by Justin Kerr. Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

The attachments likely indicate that a person has a particular skill or function. They are fastened to the front, rear, or (rarely) to the top of both Standard and Special base hats (Figures 6c–e). The most often discussed attachments are brushes, stick bundles, and hooks.

Areal distribution of Standard hats

I postulate that, despite variation in Maya culture, the Standard hats represent social roles common throughout the Maya area. If they are standard, we should find these hats throughout the Maya Lowlands. If they are throughout the Lowlands, this would challenge the idea that no system of titles existed across that area in the Classic period (Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009:171).

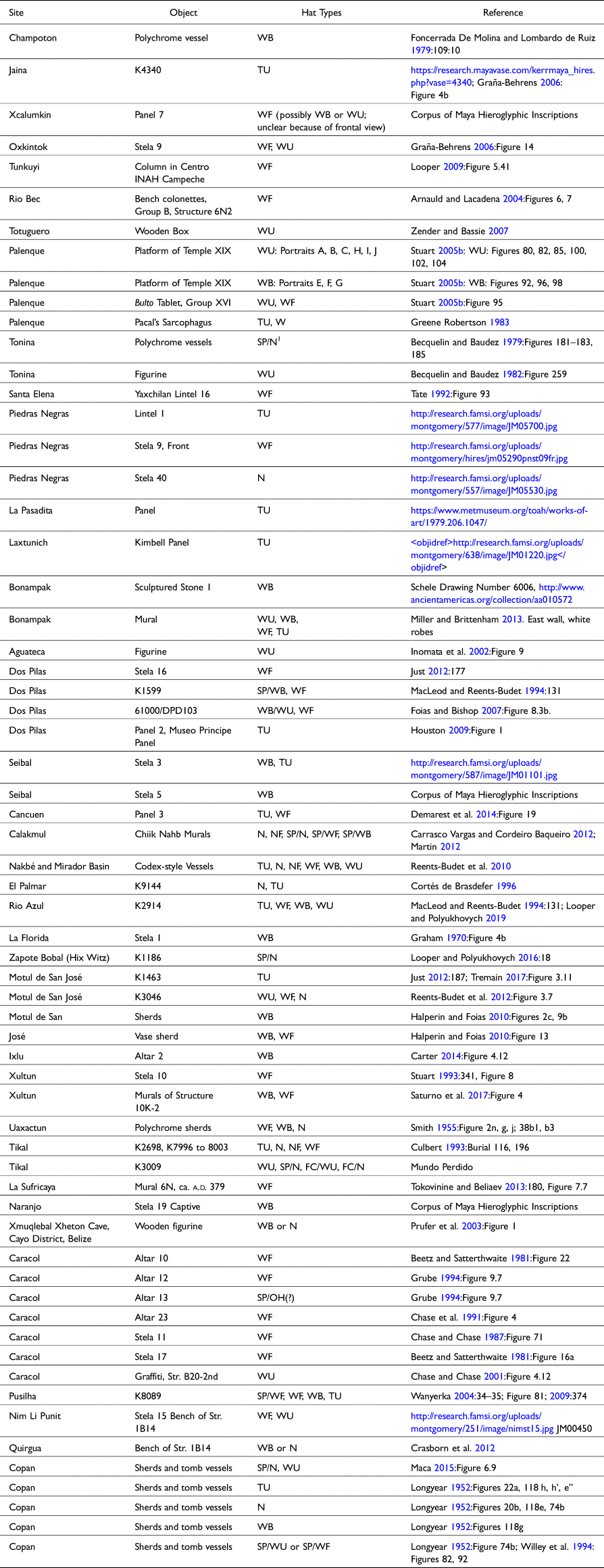

To get a clear idea of the geographical extent of Standard hats, I looked at the less mobile media, such as sculpture, murals, and published excavated sherds and vases from known contexts or workshops (Table 3). At least some Standard hats appear at 38 sites found in almost every general part of the Lowlands: north, east, west, and central. This distribution matches that of titles documented by Jackson (Reference Jackson2013:Maps 2–4). I did not include the Guatemalan highlands in this study, thereby excluding several examples. None appeared in northern Belize or Quintana Roo; these areas did not depict court scenes on sculpture.

Table 3. Distribution of hat types by location.

1 Hats with SP or FC followed by a slash and the base hat type indicate that the base hat has either the Spangled Turban (SP) or Flower Circlet (FC) added to it.

Most examples date to the Late Classic period. The earliest figure with a Standard hat wears a WF hat from the Early Classic mural at La Sufricaya, dated to a.d. 379 (Tokovinine and Beliaev Reference Tokovinine, Beliaev, Hirth and Pillsbury2013:180, Figure 7.7). The Uaxactun mural in structure B-13 dates to the same period—the Teotihuacan entrada into the Peten (Špoták Reference Špoták2017; Valdés and Fahsen Reference Valdés and Fahsen1995:32). People in the mural wear hats similar in concept to Standard hats. The paint deterioration makes the hats difficult to fit into the Late Classic categories, so I did not list the mural in Table 3. The latest example is Stela 17 from Caracol at a.d. 849 (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008).

The presence of Standard hats in these murals supports the idea that standard dress appears in Maya courts as early as the first noted appearance of titles on sculpture at Copan and Tikal (Zender Reference Zender2004). The Standard hats could be even earlier, with records of early dynasties in the first or second centuries a.d. or even the Late Preclassic period (400 b.c.–a.d. 150), when the “core ideology and symbolism of ajaw kingship” were established (Martin Reference Martin2020:77).

Others agree that the Late Preclassic sees the “basic patterns of iconographic convention” (Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube, Stuart and Hurst2005:7; see also Looper Reference Looper and Harrison-Buck2012; Valdés Reference Valdés, Laporte, Escobedo and Villagrán1993). The spread of E Groups across the Lowlands in the Middle and Late Preclassic periods “represents the coalescence of formal Maya communities that shared a unified belief system” (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017:32 ). This led to a “cultural standardization” based on religious practices structured by astronomical observations (Chase et al. Reference Chase, Dowd, Freidel, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Dowd Reference Dowd, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017).

An example of this early use of standardized headgear comes from Stela 87 of Tak'alik Ab'aj, dating to the early part of the Late Preclassic period. The head in Glyph A1 (Schieber de Lavarreda et al. Reference Schieber de Lavarreda, Orrego Corzo, Grube, Prager, Wagner, Garay, Gronemeyer, Davletshin, Mora-Marín, Gronemeyer, Prager, Chinchilla and Fahsen2022:Figure 10a) appears to have a WF hat. The person has a pointed-forward item on his head coming from what could be a support holding the hat on the head.

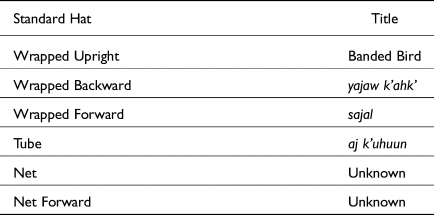

Hats and titles

Using data from both sculpture and vases, I associated four of the six Standard hats with glyphic titles (Table 4). Although it is unlikely that all the polities organized themselves in the same ways, the relative ubiquity of the Standard headgear implies that the headgear stands for common social roles. These roles can be interpreted as administrative positions within the Maya royal court. The roles have a hierarchy, as measured by which individuals are primes and which are in inferior positions. Like most models, this model of the connection between hats and titles approximates reality, especially given the scarcity of the data. I expected and found exceptions to my association of titles with specific kinds of headgear.

Table 4. Association of hat types with titles.

Only two seated titles appear on ceramic vases in short columns of glyphs tagging individuals. When they appear, titles often cannot be assigned to specific individuals, or they are assigned to individuals who are in dance costumes, as on Ik-style vessels. The ajk'uhuun title is the only one found on multiple vessels, but often the person is in a dance costume. Sajal appears on ceramics only twice: on a sherd from Tonina (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:154), and on a mythohistorical vase from Uaxactun (Carter Reference Carter2015) with no Standard hats.

Titles found in the Primary Standard Sequence are seldom linked to depicted individuals. Titles are more common on stone sculpture, and some are assigned to individuals with Standard hats.

Two complicating exceptions exist in associating titles with hats. The first is a person wearing a Standard hat who has only a nonseated title attached to them. In this case, it is likely that people with seated titles had specific duties assigned, and the nonseated title is the more appropriate title for that context. For example, people with both WF and N hats have the “baahtz'am” title.

The second is an individual with a different seated title than I assigned to that hat. These, whether on ceramics or other media, may be because people had two or more titles. We do not know under what conditions a person would wear which hat, so there could be situations in which the hat would not match the title. And we do not know why a maker would depict one over the other. This problem does not have a solution yet and limits our ability to apply the proposed model without care. However, I do not think that isolated contradictions are enough to say that no pattern exists in how dress relates to social categories.

One good example of the same person wearing multiple headgear types in different contexts is Yok Ch'ich’ Tal of Palenque. He appears in three types of headgear with different titles on Temple XIX and on the bulto stone from Temple XIV. On the latter, an eroded glyph block may have his name and profile (Spencer Reference Spencer2007:209; Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:125); his Wrapped Forward hat would point to a sajal title. On the Temple XIX bench and the stone slab, he was wearing an unusual headgear addition covered with short feathers associated with Tlaloc. On the bench, it was an addition to a WB Standard hat, and he was labeled as a yajaw k'ahk’. On the stone slab, he added two goggle eyes, characteristic of Tlaloc, and his hair projected from the top of the hat, a characteristic of an ajk'uhuun, as detailed below. A yajaw k'ahk’ on an incensario from Group IV at Palenque has a similar headgear, also with two goggle eyes (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:124). The portrait faces front, so we cannot see if this headgear was worn over a hat. Another example of this same combination of a WB with the short-feather headgear occurs on a sajal performing a ceremony on Altar 4 at El Cayo (see Jackson Reference Jackson2013:41–44). A partially destroyed title glyph could suggest the El Cayo sajal held the yajaw k'ahk’ position as well (Zender Reference Zender2004:321). The hair projecting from the back of the WB is tied, which is not typical of an ajk'uhuun. Given that the short-feather type appears on individuals with three different titles, it is likely a sign of an activity or event.

This seeming contradiction shows how the Maya used material culture to signal different aspects of a person's social identity. They did this by adding embellishments to the person's base Standard hat in the form of additions and attachments. It also shows the complexity of signaling multiple roles and the need for a model to start exploring them.

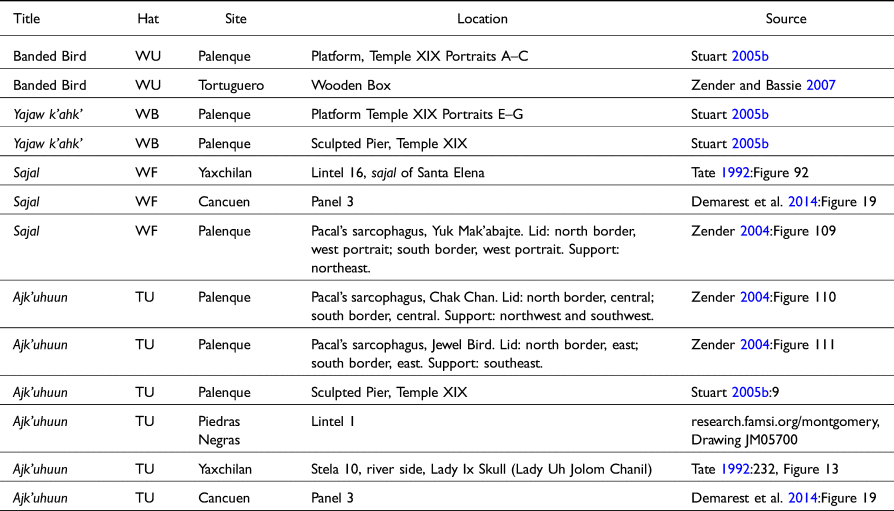

Wrapped Upright hat

People wearing the upright wrapped hats (WU) (Figure 5f) were not labeled on vases, but such hats were labeled on the platform of Temple XIX at Palenque (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b) (Table 5). Three people (Portraits A–C) were on the right of the ruler K'inich Ahkal Mo’ Nahb, who was receiving the sak huun of rulership from the first of these (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:131–136). They had the banded bird title. Three other individuals on the west side of this platform also had WU hats (Portraits H, I, and J) but without attendant titles. That there are six people with banded bird hats implies multiple individuals in the banded bird role. This suggests that the people with this title were members of a priesthood at Palenque or were banded birds from nearby communities, such as on the Tabasco Plain (Straight Reference Straight and Markam2007:187–188; Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:131). It also suggests ranking within the title, or that every community had their own banded bird.

Table 5. Standard hats on people labeled with titles on other media.

This idea that the banded bird position exist in other communities is supported by a carved box from Tortuguero, from the same region as Palenque. The box shows an individual with both the banded bird title and the WU hat. The box was made for an individual who was seated as a banded bird after the accession of the local ruler (Zender and Bassie Reference Zender, Bassie and edited by Arthur2007).

A conflicting example exists for identifying the WU hat with the banded bird title. Two examples of figures with WU hats are labeled as ti'sakhuun. The Palenque bulto stone is one instance with the title associated with a wearer of a Wrapped Upright hat (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:124). The other is the figure on the left side of Piedras Negras Stela 11, the ruler's right side (Zender Reference Zender2004:324). He wore what could be a Spangled Turban on a Wrapped Upright hat, although the shape is not clear. I did not include it in my data as an example of a WU hat because it is smaller and of different shape.

Wrapped Backward hat

The Wrapped Backward hat (WB) (Figure 5e) was not labeled on a vase and rarely labeled on sculpture, but it was on the same Palenque platform in Temple XIX (Table 5). The three figures to the left of the ruler had WB hats. The person closest to the ruler was Yok Ch'ich’ Tal (Portrait E), labeled yajaw k'ahk’. The two behind him with the same hat certainly bore the same title, although they lacked the short-feather addition over the WB hat, suggesting a ranking among those with the title. Stuart suggests that the title, translated as “Fire Lord,” was used for elite individuals from the royal lineage at Palenque (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:119). Analysis of this title has suggested that it could be a military title or one associated with priestly duties, such as taking care of the drum major headdress (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:20), which sat between the yajaw k'ahk’ and the ruler. As mentioned above, it might be associated with Tlaloc. The case of Yok Ch'ich’ Tal and the sajal from El Cayo were discussed earlier.

Wrapped Forward hat

The Wrapped Forward hat (WF) was the most common type in my vase sample (Figure 5d), and I associate it with the sajal title (Table 5). The title appears on sculpture but only twice on ceramics, as mentioned earlier. A few people on sculpture were labeled sajals when not dressed for rituals at Palenque, Yaxchilan, Cancuen, and Xcalumkin. One from La Mar Stela 1 is provisional because the photo (Maler Reference Maler1901:Plate 36:2) is not clear, but a section of the headgear is bent forward. Mayanists in general believe sajals to be rulers of smaller subsidiary sites and subordinate to the rulers of major sites. But they also had roles at major sites (Jackson Reference Jackson2013).

People wearing this most frequent hat (17 percent of all hats) had many duties on vase scenes. They were the main musicians; they held mirrors for the ruler, helped him dress, and painted his body. They held spears and banners and presented tribute. A common motif was a figure behind the throne looking to the right, away from the ruler, as if in a guard position. Three of the six times this motif appeared, the person wore the WF hat (K1790, K5450, K6341). On the Xultun mural, the person behind the throne wearing the WF hat had the baah tz'am (“head throne”) title. These duties could all represent honorific positions for trusted nonroyals or distant relatives.

Some minor sites had records of the same family holding the sajal title for five centuries (Bíró Reference Bíró2011; Jackson Reference Jackson2013), and Stuart (Reference Stuart, Sabloff and Henderson1993:330) has suggested there was little real difference between ajaw and sajal. For example, the baah ajaw wearing a WF hat was not labeled as a sajal on K2914. Altogether, observations suggest “a sajal may inherit his status but acquired its essence, its sajal-ship (sajal-il), only through rituals of enthronement” (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001:61). The elite who were not seated but played administrative or religious roles may have comprised a group of nobles who accepted minor honorific duties in the court. They also may have earned other nonseated titles, such as anahb and baah tz'am. In summary, it might be that unseated sajals were a broad class of nobles eligible to take part in court activities, from whom rulers could select office holders. Whether that would have been by kinship or achievement is unknown.

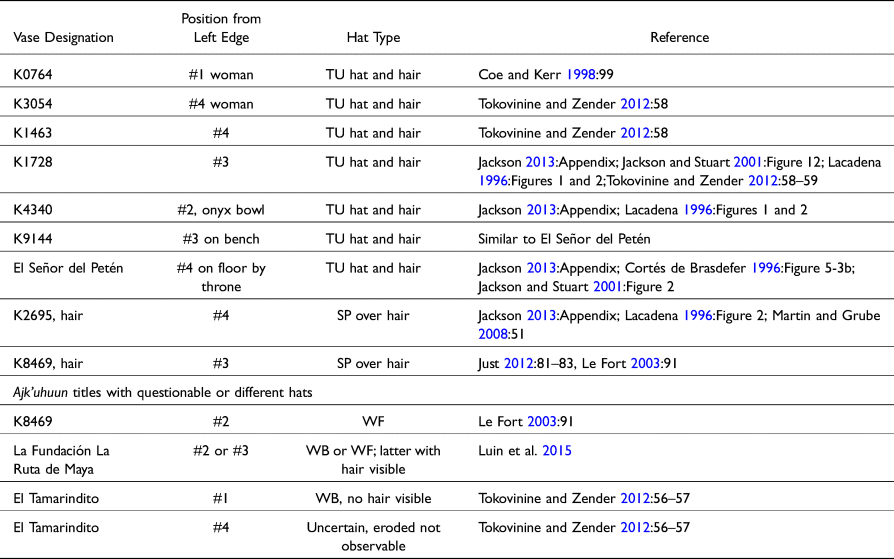

Tube hat

The Tube hat (TU), often called a head wrap, has hair, often matted or braided, that is visible from the top (Figure 5c). I associated this hat with the ajk'uhuun title. The hair is an important element because this is the only hat that consistently showed exposed hair. Coe first connected the hat with the title on Lintel 1 from Piedras Negras and the stone vase K4340 (Coe and Kerr Reference Coe and Kerr1998:92–94). Other sculpture examples with the title and the hat exist on six items (Table 5). Some had the hat and the hair, whereas others only had the hair. Long hair is shown sometimes for an ajk'uhuun, even when the individual is wearing ritual headgear. This is the case with Ahkmo’, a leader of Site R (La Pasadita), who performed in ritual clothing with his ruler, Bird Jaguar IV, on Lintel 4 at Yaxchilan (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:Figure 16). His appearances on two other monuments (Site R Lintels 1 and 3) do not show him with hair while wearing ritual headgear.

Wearers of these hats were a common presence in court, making up 16.1 percent of the those with Standard hats and 9 percent of all hats. Twelve people (including two women) not in ritual or warrior dress had been tagged on vessels as ajk'uhuun (Table 6). Of these, six figures had the TU hat and the hair, and two had the Spangled Turban over projecting hair. Three other vessels did not have all or any TU standard elements: K8469, La Fundación La Ruta de Maya vase, and El Tamarindito vase. On K8469, it is not clear to which person the title belongs. For this vase, it does not matter, given that neither person fits. On the La Ruta vase, it also is not clear to whom the title belongs, but a WB and WF hat are candidates. On the El Señor vase, one title is located closest to a person with a WU hat; but people with an N and TU are nearby. The El Tamarindito vase applies the title to two figures: one who has a WB hat, and another whose hat is too eroded to identify. It is possible that glyphic tags were assigned to the wrong person by me or by the vase analyst.

Table 6. Standard hats on people labeled as ajk'uhuun on vessels.

The functions assigned to the aj k'uhuun have been varied, depending on how the word is translated. One of more frequent suggestions is that they functioned as scribes, although the ones most used now are “he who guards” or “he who venerates” (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:13; Jackson and Stuart Reference Jackson and Stuart2001). The scribe function was based on the attachment called the “stick bundle” under the tie on their hat and the occasional presence of a hook (Coe and Kerr Reference Coe and Kerr1998:91–96). However, all the Standard hat types sometimes bore the hat attachments suggested as scribal. Another suggestion beside scribe is that the individual was the chief tribute collector (Jackson and Stuart Reference Jackson and Stuart2001:225; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet, Guernsey and Keny Reilly2006:112). This idea may become more likely if the stick bundles often found on ajk'uhuun hats are tally sticks for recording tribute (see Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2017; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020).

This hat type has all three of the common attachments: the stick bundle, the hook, and brushes often associated with scribes. Some attachments were more frequent on one hat type or another. In the Standard hats, 32 percent of the stick bundles occurred on TU hats, but the other 68 percent were divided among the five other hat types with from 2 to 7 percent each. Consequently, it is not likely that this is the only hat that signals the wearer is a scribe, if that is what it signals.

Net hats: Net Backward and Net Forward

Human figures wearing the Net (N) hat (Figures 4 a–b) have not been labeled on vases with any recognizable title. The only example on sculpture I have found is Piedras Negras Stela 40. On this monument, the ruler was performing a ritual for an ancestor. It also did not appear on the various scenes on panels and lintels with nonroyal nobles.

The nonquotidian social and political contexts in the Bonampak murals had all the hat types but no identifiable Net. In contrast, Net hats were plentiful on the Chiik Nahb market-scene mural, with their wearers taking a meal or participating in the market (Carrasco Vargas and Corderiro Baqueiro 2012; Carrasco Vargas et al. Reference Carrasco Vargas, Vázquez López and Martin2009; García-Barrios and Carrasco Vargas Reference García Barrios, Vargas, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2008; Martin Reference Martin, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2012). Perhaps this difference in scene type means that wearers of this hat were not required participants in sculptured scenes of a ritual or political nature. Rulers did not wear them with their ritual garb on stelae either (except Piedras Negras Stela 40). Two vases showed groups of people with either Spangled Turbans (K5611) or Flower Circlets (K3009) on N hats. On the latter vase (K3009), a group of men, playing music, preparing for dancing, and dancing, suggested that the N hats were part of certain group ritual activities.

Unlike the other hats, N hats had two variants. An artistic variant showed a red or white crosshatched pattern for this hat rather than the mesh of the other vases (K625, K680, K764). The other variant, scroll decorations (Figure 6d–e) was seen on vases K3009, K2800, K5609, K7021; the Lord of the Jaguar Pelt Throne vase; and Piedras Negras Stela 40. The scrolls appear painted on stiffened nets. A third possible variant, or even a different hat, is the bag hat of Itzamnaah on K1196, which does not have the dark strip the net hats do.

Mayanists have linked Net hats to scribal activity, mostly because Itzamnaah is the patron of writing and sometimes wears the similar bag hat. The data from Copan's 9N-82 structure (Fash Reference Fash and Webster1989:69) (the façade sculpture and the pauahtun/Itzamnaah sculpture in the fill) links Itzamnaah to scribal activity. But no ajk'uhuun, like the one who lived in the structure with this evidence, wore a Net hat.

We have no evidence that people wearing Net hats were the only scribes, although scribal duties were important in their occupations. I know of only one example of a human-interaction scene that showed a person with a brush and codex, and that person wore a WB hat, not an N one (Halperin and Foias Reference Halperin and Foias2010:Figure 2c). Even in mythological scenes, only one vase (K4010) had a figure with an N hat holding a brush over a paint pot. However, “The Court of God D” vessel shows the link of literacy and numeracy to Net hats. There, Itzamnaah's animal assistants wore Net hats and held a codex and a “printout” with Maya numbers on it.

Finally, we have no evidence that the wearers of Net hats are seated, as some other titles are. Their frequency on vases, their wide distribution, and their association with supernaturals means their activities were important but, in some way, distinct from the kind of positions represented by the other Standard hats. But although their role was important, they never appear in sculpture in public ceremonial contexts, and only once did a narrative scene show an active scribe on pottery (Halperin and Foias Reference Halperin and Foias2010:Figure 2c).

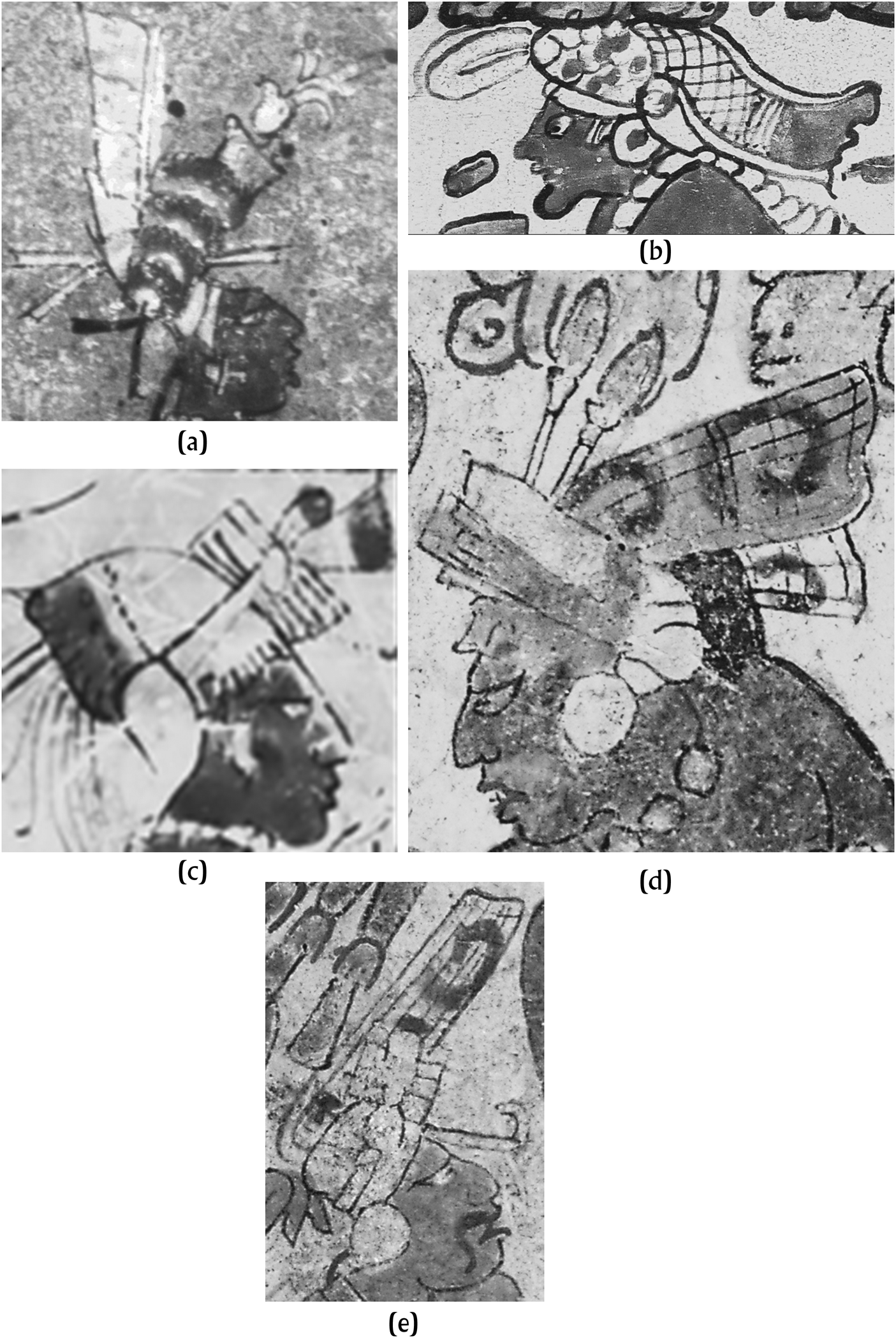

Hierarchy

A hierarchical system places people or things in ranks and controls, to some degree, their actions in different contexts (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2011). It generally assumes a greater expression of power with an increase in rank. A heterarchical system has “elements either unranked relative to other elements or possesses the potential for being ranked in a number of ways” (Crumley Reference Crumley, Pattern and Gailey1987:158). This results in counterpoised power that can create a dialectic between hierarchical and heterarchical elements (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2011:5; Crumley Reference Crumley, Pattern and Gailey1987:164).

Existing Maya communities have overlapping hierarchies based on age, civil-religious organizations, rituals, and wealth (for example, Mayén de Castellanos Reference Mayén, de Castellanos1988 and Rosaldo Reference Rosaldo1968, among many others). We do not know the structure of the Classic Maya ranking system. A court could have heterarchical elements as well as hierarchical ones, with the expressed relationship between two people changing based on the interaction context.

The depictions on vases materialize ranking at a particular instance. Within visual space, artistic conventions are used to show who has the most importance. In the Maya vase painting, the main figure—here called the prime—is elevated over others, is larger, and faces his right, but his body is seen in a frontal view (Loughmiller-Newman Reference Loughmiller-Newman2008; Palka Reference Palka2002). This positioning indicates a hierarchical relation with a prime figure facing his right and an opposing one, who is usually seen in profile, with various attendees also in profile behind the two confronting individuals.

In three cases, where the interactors wear Standard hats, the hierarchical relationship of prime and opposing person is reversed, suggesting that some other factor besides power is at work. A ritual hierarchy could require a reversal of roles. An event could be overseen by groups that are not formally ranked. A person may move to a higher position, even if temporarily, by taking up a specific role and be required to be a prime in that context.

The vases show two separate sets of hierarchical relationships: those found on vases with primes wearing Special headgear, and those where they wear Standard hats. Those wearing Special headgear were opposed by Standard hats about 1.5 times more than Special ones. Those primes with Standard hats were almost three times more likely to be opposed by those in Standard hats than in Special headgear.

Special hats were probably worn for specific ceremonies, and their variety made it difficult to say much more about them. The people who wore the Headdresses, Tied Hair, Other Hair, and Miscellaneous appear in a primary position over all the wearers of Standard types, with few exceptions. Tied Hair was not over WB, and Miscellaneous was not over N.

Wearers of Tied Hair were never in the second position. Tied Hair was most often over wearers of Standard hats (N, TU, WF, and WU) and hats with Spangled Turbans and Flower Circlets. In the Special group, Tied Hair was over only Zoomorphic hats. Tied Hair headgear was therefore mainly associated with Standard hats and may have represented a ruler imitating a supernatural attended by members of the court. For example, on vases with mythical scenes, Chahk is known for having a tied hank of hair projecting over his forehead.

The hierarchy of the Standard hats was more straightforward (Figure 7). The basic situation had those wearing the WU hat (banded bird) over those wearing other types of Standard hats. The ranking was WU, TU (ajk'uhuun), WB (yajaw k'ahk’), WF (sajal), and N and NF hats. The last two (N, NF) reversed position: WF was over N once and over NF five times, whereas N was over WF twice. Primes also wore the same hat as those opposing them but infrequently (17 percent). Even fewer (12 percent) of attendees had the same hat as their prime, suggesting that the events depicted were not held for those of the same rank or position. There was only one exception to this basic hierarchy of Standard hats: the Denver vessel (Tremain Reference Tremain2017:Figure 5.39) has a prime with a Flower Circlet added to an N hat. It seems unlikely that an N hat would be worn at an accession scene. This vessel may have been “restored,” as others have suggested. However, it has people with WU hats on the left and a WB hat on the right like the Palenque Temple XIX bench.

Figure 7. Hierarchical relations among figures wearing standard hats.

Those wearing the WU hat are not subsidiary to any other person wearing a Standard hat. It is likely they are subsidiary only to rulers, who wear different Special hats depending on the event. Also interesting was that those with WU hats in the attendees’ group were mostly behind the ruler (11 of 14), and six of those were standing. These can be interpreted as people supporting the prime figure.

Two exceptions showed ranking within the banded bird position. In K2732, one banded bird was kneeling to another, and both wore Flower Circlets. The other was the Denver vase, discussed above. Here, two WU were kneeling to a prime with an SP/N hat while he sat on a throne cushion. All are wearing Flower Circlets.

The hierarchical position of the banded bird category is clear from the vases. However, the relative position of the yajaw k'ahk’ (WB), the ajk'uhuun (TU), and the sajal (WF) conflicts with the Palenque data, which is the only textual source of ranked relationships among these titles. The information from Palenque both supports and refutes the organization in Figure 7. At Palenque, a sajal possessed an ajk'uhuun, which placed the sajal in the superior position (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:34; Zender Reference Zender2004:298). The Palenque texts also showed a ti'sakhuun (Bíró Reference Bíró2011:109; Zender Reference Zender2004:307) possessing sajalob, who were then made yajaw k'ahk’. That suggests the latter were more important than the former, given that the sajalob were then raised to a new seated title. It also suggested the sajal might be an underlying group of noble but nonroyal elites who were called on for significant duties depending on the circumstances. Houston and Stuart (Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001:61) surmised the sajal were born into their title but only seated in it when they moved into specific duties. Courtiers often held both ajk'uhuun and yajaw k'ahk’ titles; this suggests they may have been equivalent in some ways. For example, we know they both accompanied rulers into battle (Zender Reference Zender2004:309) and were occasionally captured and displayed as captives (Zender Reference Zender2004:405–407). However, I have observed that individuals often received the ajk'uhuun title after the yajaw k'ahk title, suggesting that it was more important.

In summary, the number of cases where the hierarchical position on vases were reversed is small, suggesting that it was the Maya “normal” ranking system unless contexts changed. The sequence in Figure 7 conflicts in some ways with the equally limited Palenque textual data. A possible explanation of the reversals is that the events overseen had a ritual hierarchy that required a person with one title to take precedence over the other, a possible example of heterarchical groups or events. Most of these reversals occurred in events hosted by bearers of either Flower Circlets or Spangled Turbans, who oversaw specific events. The partially different Palenque data may suggest that different preference or merit systems existed in different polities. Additional data are needed to resolve these issues.

Headgear analysis

The hierarchical distribution of the courtier titles in my analysis is based on who was below another person in the scenes. Some numbers are small, but a look at the percentage of distinct kinds of hats on courtiers in different positions on the vases supports the simple hierarchical analysis (Figure 8). The distribution of the headgear shows that some were worn more by primes. In general, they were not evenly distributed in the three spatial positions, as shown by a simple chi-square test. This was especially true of the Standard hats.

Figure 8. Percent of hat types by headgear group and visual position. They are sorted by the frequency of the prime hats. (Standard hats: chi-Square p-values: <0.0001; Special hats: chi-square was not valid since more than half the expected cells were less than 5).

In the Standard hats, the WU hat (banded bird), at 13 percent of the Standard hats (Table 1), is on the most primes (32 percent). The WF hat (sajal) is the most common hat, at 30 percent of Standard hats, but only 15 percent of primes wore this hat. The WB (yajaw k'ahk’) and N hats are on about 21 percent of the primes, slightly more than their 17.2 overall percent (Table 1) in Standard hats. The TU (ajk'uhuun) hats are on only 7 percent of the primes, in contrast to their 16.1 percent of Standard hats. NF hats were about three times less frequent on primes than their overall presensce in the Standard hat sample. The most direct support of the hierarchy analysis is the position of those wearing banded bird hats. These hats are most frequent on primes, and those wearing sajal hats are mostly in opposing and attendee positions.

The major differences in which titled person wore which addition implies that some titles were more connected to some events than others (Figure 9). The banded-bird role wore the Flower Circlet the most, emphasizing the importance of whatever this event was. It is important to note that the ajk'uhuun wore this addition the least. The two lesser positions in the hierarchy, wearing WF and N hats, had larger roles in ceremonies where Spangled Turbans were worn. Neither ajku'huun (WF) nor banded bird (WU) wore many Spangled Turbans.

Figure 9. Count of standard hats with different additions, sorted from least to most within each addition.

Discussion

This analysis of dress focused on one medium—vases with humans interacting in court scenes—and it evaluated how the producers’ view of their audience affected their goals. Although an audience can interpret messages, both verbal and visual, in ways different from producers’ expectations, we need to consider what the producers were trying to convey. Given that the scenes show interaction among humans, we can interpret them as commemorations of important human events, but different from those on stelae. Most Mayanists accept that vases were part of displays increasing the political profile of a polity and its ruling elite within the polity. If this is so, they should have enough information for their selected audience to understand the scene with or without text. One way to do this is to have the participants dressed as they normally would be, showing their specific positions in the court. The audience for these scenes would include royals and elite nonroyals in their home polity and in other polities (Jackson Reference Jackson2009:73).

My review of the headgear data has three implications. First, four of the six Standard hats could be connected to titles: the Wrapped Upright hat with banded bird, the Tube hat with aj k'uhuun, the Wrapped Backward hat with yajaw k'ahk’, and the Wrapped Forward hat with sajal. Although a few contradictions exist, the model has enough support to use it to explore relationships and functions of the court. The Net hats have not been tied to titles yet, but they are related in some way to things scribes did. They could belong to individuals with nonseated titles such as “wise one” (itz'at). This work supplements that of Jackson (Reference Jackson2013) and Tokovinine and Zender (Reference Tokovinine and Zender2012), who examined individual names in texts to understand who was doing what in Maya courts. We can now look at people without associated texts and see how they act in court settings.

Second, Standard headgear and the associated titles were widespread, but Standard hats were missing in some eastern areas. This artistic, and possibly political, trend did not spread there until late, if at all. Perhaps that area had no tradition of narrative sculpture or pottery. Caracol, for example, did not have narrative sculpture until after a.d. 800.

Third is that the Standard headgear tradition dates to at least the Early Classic period. Earlier visual data, such as the San Bartolo murals, show only headdresses and the royal headband. These do not provide early examples of position-signifying hats; but it seems that by the Early Classic period, at least some of these positions were in existence. Earlier evidence, such as the glyph from Tak'alik Ab'aj in the Late Preclassic period, is suggestive but preliminary.

It is still not clear, despite Zender's (Reference Zender2004) extensive investigation and arguments, what dress or accouterments identified priests, and I cannot address that issue in detail here. However, current evidence suggests that different religious specialists have different headgear. It is likely that at least the Wrapped Upright hat, as Zender (Reference Zender2004) concluded, was worn by a priest. At Palenque, the highest-level priest who comes from a specific lineage wears this hat. The Wrapped Backward hat is also probably a religious specialist's hat based on its association with military and religious activity at Palenque. The evidence does not connect the Net and Net Forward hats to a title, seated or unseated, and it is unclear if they were a kind of religious specialist. I doubt that either the Wrapped Forward (sajal) or the Tube (ajk'uhuun) hats mark a religious specialist. The sajalob’s role in ritual dances, as documented by Parmington (Reference Parmington2003), does not mean they are priests. Dances were part of rituals that many kinds of people took part in, as shown by the Bonampak mural and various Ik and other vases. The ajk'uhuunob also danced, often in supporting roles as musicians, but again, this does not make them priests.

Four common Standard hats signaled four titled persons. Their wearers functioned as the political-religious administration for the ruler, as others have suggested. Various scholars have commented that this group had flexible duties, partially because of a lack of data. However, this study supplies a distinct perspective, especially on how courtiers were chosen. I suggest that the courtiers were drawn from an ajaw or sajal class that had an inherited basis. Within this base group, some positions were inherited through lineages, such as the banded bird and the yajaw k'ahk’, if Palenque is representative of other polities. Some sajalob in charge of communities also were in inherited positions. A ruler chose an ajk'uhuun on personal relationship, or skills, or political expediency, as inferred from Copan's example. The choice could come from people in inherited or achieved positions, given that the ajk'uhuun title was usually the last of the series of titles individuals received. This suggests that courtiers could move through a series of positions and that not all seated positions were inherited (Jackson Reference Jackson2013). We know the least about those wearing Net hats because texts never mentioned them.

The distribution of brushes to hats suggests that almost any courtier could be literate. Numeracy also seems widespread if stick bundles are tally sticks. Most of those with seated titles can host or oversee activities represented by the Flower Circlet and Spangled Turban. With this view of the relation of dress to titles, we can develop new understandings of courtier behavior. The murals at Chiik Nahb, for example, have a sajal marketing cloth (Garcia Barrios and Carrasco Vargas Reference García Barrios, Vargas, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2008:Figure 7), expanding our view of who engaged in market behavior.

Conclusions

I had two purposes in the article. The first was to restart a discussion on using dress as artifacts to understand the social structure of the Maya court. We need to look at dress as a material culture complex with the body as a complex artifact that we can study with standard archaeological methods. European scholars have been applying chaîne opératoire methods (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier1986), like behavioral chains (Schiffer Reference Schiffer2016), to dress for some years (Andersson Strand Reference Andersson Strand2012; Harlow and Nosch Reference Harlow, Nosch, Harlow and Nosch2014). Various Mesoamericanists have looked at the material culture of weaving, specifically spindle whorls, but few have looked at how cloth was used to create clothes.

The second purpose was to use dress to examine the structure of the Maya court. My underlying assumption is that patrons and artists wanted vase scenes to be commemorative and understandable. Few links exist between glyphic titles and activities, so most scholars speculated there was flexibility and variation in which title did what. Most speculations depend on translating the titles, but there may be no connection between the origin of the word and the activities (personal communication, Marc Zender 2020).

With this model, we now have a place to start the analysis of narrative scenes rather than assuming we understand the contexts depicted. We need to look at the material culture in the scenes to see if different members of the court had specific duties. The material culture may help identify the link between title and activities. Another need is to look at other elements of dress, such as jewelry, in relation to hat types and to expand on the initial study of body painting (Nehammer Knub Reference Nehammer Knub, Knub, Helmke and Nielsen2014).

In conclusion, I cannot agree with those who say that statuses or social categories were not signaled by Maya dress. Widespread evidence shows that the Maya signaled social categories and, therefore, social relations by dress. My model identifies overlapping sets of dress elements that referred to social position, events, and skills. Their overlap created a perceived complexity in dress that was seen as not understandable, and dress was ignored as a topic in and of itself. However, there was no lack of cultural rules or dispositions to use dress to structure social relations in the Maya court.

Acknowledgments

The research presented here was supported by a One Month Research Award from Dumbarton Oaks in 2014. I acknowledge thanks to Dorie Reents-Budet, Arlen Chase, Anne Dowd, Marshall Becker, and Kevin Leehan for their support and encouragement. Marc Zender and Péter Bíró answered some questions for me. My wife, Annetta, helped with final editing. I would also like to thank the former Director of Pre-Columbian Studies, Colin McEwan (unfortunately no longer with us) for the help he provided while I was at Dumbarton Oaks.

Data availability statement

The author will provide copies of the base data to any interested researcher.

Notes

List of vessels in the study sample.

Kerr Archive

532, 625, 679, 680, 751, 764, 767, 787, 868, 1092, 1151, 1186, 1205, 1210, 1453, 1454, 1549, 1563, 1599, 1643, 1728, 1775, 1790, 2697, 2698, 2699, 2711, 2732, 2780, 2783, 2784, 2800, 2914, 2923, 3008, 3009, 3026, 3046, 3050, 3203, 3460, 3461, 3983, 4030, 4096, 4120, 4169, 4338, 4355, 4606, 4688, 4825, 4959, 5037, 5062, 5085, 5094, 5176, 5233, 5353, 5370, 5388, 5416, 5421, 5445, 5450, 5453, 5456, 5505, 5513, 5611, 5649, 5738, 5850, 5858, 5940, 6059, 6067, 6315, 6316, 6341, 6418, 6437, 6494, 6552, 6610, 6666, 6688, 6812, 6984, 7020, 7021, 7062, 7182, 7183, 7184, 7288, 7690, 7796, 7797, 7996, 7997, 7998, 7999, 8001, 8002, 8003, 8006, 8089, 8123, 8220, 8385, 8386, 8469, 8652, 8746, 8764, 8774, 8790, 8792, 8793, 8818, 8873, 8889, 8926, 9094, 9109, 9135, 9144, 9190, 9290, 5195/6613, 5609/3389.

Other Sources

Caracol, Building B5 Vase: Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Inomata and Houston2001:Figure 4.13.

Tamarindito Vase: Valdés Reference Valdés1997:Figure 11.

La Ruta Maya Vase: Luin et al. Reference Luin, Tokovinine, Beliaev, Arroyo, Méndez and Aragón2015:Figure 1. La Ruta Maya Fundación, Guatemala.

Lord of the Jaguar Pelt Throne Vase: National Gallery of Victoria Melbourne.

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/the-lord-of-the-jaguar-pelt-throne-vase/

Denver Art Museum Vase: Tremain Reference Tremain2017:Figure 5.39