INTRODUCTION

The urban/rural dichotomy applied to Classic Maya lowland societies makes little sense in view of ethnographic and ethnohistoric data of the Maya area. In archaeology, however, it is still a useful tool to technically approach the physical landscapes, i.e., to hierarchize sites that form a settlement system within a region. Since the 1950s, settlement typologies based on several criteria and applied at different spatial scales (Bullard Reference Bullard1960; Willey Reference Willey1956) have been successfully adopted. Besides quantity and size of public places and monuments, among these criteria structure density is still very commonly used to define region or sector subdivisions as epicenter/center/urban core, or as urban (residential) zone, peri-urban (peripheral) zone, and beyond, rural zone or hinterland (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováĉ, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drapela, Lieskovsky, Tokovinine, Velasquez, Fernandez-Diaz and Shrestha2018). The first intersite surveys carried out in the Maya area (between Tikal and Uaxactun [Puleston Reference Puleston and Hammond1974, Reference Puleston1983], Tikal and Yaxha [Ford Reference Ford1979, Reference Ford1991], and Yaxha and Sacnab [Rice and Rice Reference Rice and Rice1980]) validated the image of a densifying landscape at the door-step of the cities: whereas the intermediate sectors of intersite transects are characterized by low residential density, the extremities show higher density, although lower than in both cities themselves, so that the boundaries of urban settlements are defined by a break of structure density and sometimes by physical limits (e.g., swamp, earthwork, wall, and vacant spaces, among others). These early investigations, as well as previous rural studies conducted since the 1930s (Wauchope Reference Wauchope1934, Reference Wauchope1938; Willey and Bullard Reference Willey, Bullard and Willey1965) and many later regional settlement surveys (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1981; Freter Reference Freter, Schwartz and Falconer1994, Reference Freter2004; Gonlin Reference Gonlin, Schwartz and Falconer1994; Kurjack Reference Kurjack1979; Vlcek et al. Reference Vlcek, Garza de González, Kurjack, Harrison and Turner1978; Vogt Reference Vogt, Vogt and Leventhal1983), warned, however, against a simplified view of a rural world traditionally considered as the subsistence area of the cities. Beyond “urban limits” there is a practically continuous network of households and agricultural features (Fedick and Ford Reference Fedick and Ford1990; Liendo Stuardo Reference Liendo Stuardo2002) revealing non-urban settlements with different spatial layouts and morphologies almost as heterogeneous as those found in cities (Iannone and Connell Reference Iannone and Connell2003). As for agricultural features found in hinterland areas, they continue to raise the issue of agricultural production controlled by elites (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1992, Reference Chase and Chase1996; Puleston Reference Puleston1977; Scarborough Reference Scarborough, Scarborough and Issad1993) or that of communities' autonomy or interdependence (Fedick Reference Fedick1996; Netting Reference Netting1993; Pyburn Reference Pyburn1998; Robin Reference Robin2002). To some degree, elites have always been associated with urban contexts, and commoners with rural (and supposedly dependent) contexts.

Structure densities, equivalent to settlement density on cultivable land (Puleston Reference Puleston1983:24, Figure 21), however, are not sufficiently specified in space to help us discern and define social communities. Many studies conducted after the 1970s intersite surveys and before the quite recent analyses based on Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) captures (Beach et al. Reference Beach, Luzzader-Beach, Krause, Guderjan, Valdez, Fernandez-Diaz, Eshleman and Doyle2019; Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováĉ, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drapela, Lieskovsky, Tokovinine, Velasquez, Fernandez-Diaz and Shrestha2018; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019; Ruhl et al. Reference Ruhl, Dunning and Carr2018) suggest the existence of urban/rural relationships that outreached economic activities, i.e., food production and redistribution of goods. For example, some recent works identify discrete settlements that would have been linked by sacbes and/or collective spaces, and discuss the role of these built infrastructures as a way of defining site boundaries, sociopolitical dynamics, and symbolic relationships (Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Kidder, Lamb, Vallejo-Cáliz and Welch2016; Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Lemonnier, Purdue, Hiquet, Castanet, Marken and Arnauld2022; Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Ardren, Barth, Fernandez-Diaz, Patrick Rohrer, Meyer, Miller, Magnoni and Pérez2019). The detailed study of architecture and material artifacts is also helpful in enlightening the nature of urban/rural relationships (Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Hixson, Magnoni, Mazeau and Dahlin2008, Reference Hutson, Hixson, Magnoni, Mazeau and Dahlin2009), even adjusting and rethinking the notion of urban/rural limits. Other studies propose that this dichotomy be canceled and conceive a “conurban landscape” on a regional scale, that is “an articulated socio-political landscape” with “villages, homesteads, fields, forests, orchards and cities” under the authority of a supra-regional political power (Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019:143). In such a perspective, the amplitude of agrarian investment and the required political coordination managed at different levels of the society are posited conjointly. At this point, ethnohistoric and ethnographic information remind us that Mesoamerican people may not have made the same conceptual distinctions between urban and rural environments as Western European sociological models (e.g., Redfield Reference Redfield1941). In particular, Marcus (Reference Marcus, Z. Vogt and Leventhal1983:206–208) gave attention to what seems to be an emic lack of the urban/rural dichotomy so central to Western concepts of urbanism. This can be debated (see Smith [Reference Smith, Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008a:457, n2] concerning the Aztec concepts of city and altepetl, and Breton [Reference Breton and Ichon1982] on Maya modern settlements). Smith (Reference Smith and Smith2003:4) warns that “the concept of a firm ‘rural-urban’ divide is also problematic when the same individuals move back and forth from one setting to another,” an observation which induces to take a practical rather than conceptual stand on the issue (also Smith Reference Smith2008b:172–173, 176).

In brief, three methodological prerequisites seem relevant to address the topic of rurality: (1) Along with the evidence obtained from the study of settlement and land use patterns, we have to mobilize other datasets to characterize relationships among populations living in spaces with fuzzy/diffuse boundaries, considering that social relationships often overpass physical limits, and that those limits were actually multiple and operated on different socio-spatial scales. (2) Thus, thinking beyond the notions of boundary and distance—even though both are the basis for spatial analysis in archaeology—opens the way to a fuller understanding of social relationships, and means selecting a broad observation window to carry out multiscalar analyses dedicated to compare target populations and explore their plausible activities and interactions. (3) On behalf of a reciprocal relationship between rural and urban populations, it does not seem relevant to study them separately but instead to consider economic connections, sociopolitical interactions, and their evolution in time as having shaped the layout of both categories of space and impacted their longevity in occupation. As noted by Iannone and Connell (Reference Iannone and Connell2003) and Lamoureux-St-Hilaire et al. (Reference Lamoureux-St-Hilaire, McCane, Parker and Iannone2015), generally Maya rural areas were abandoned later than cities.

With these prerequisites in mind, investigations carried out at the site of La Joyanca allow us to explore the topic of rurality. Two research projects that were focused on the history of this small city within its regional framework were developed in succession in 1999–2003 and 2010–2013. Whereas the early project contextualized the city in an area then largely unknown through surveys on a regional scale in parallel with excavations done within the city (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a; Forné Reference Forné2006; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009), the later project was centered on urbanization processes to test hypotheses derived from the previous research and thus more directly included rural populations in the research agenda (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017). The second season of fieldwork, however, did not permit excavating hinterland sites, limiting our evidence on local communities to survey data. As detailed in this article, the datasets that have been assembled during both projects on settlement, land use pattern, architecture, and population mobility are nevertheless sufficient to explore the issue of the relationships between the center of La Joyanca and its hinterland. We would document the way the first three parameters introduce and determine the fourth (mobility), which has basically to do with not only the attraction of cities, but also a more complex capacity of “bottom-up” agency of commoners (Hutson Reference Hutson2016; Inomata Reference Inomata, Lohse and Valdez2004; Marken and Arnauld Reference Marken and Arnauld2022).

The available evidence suggests that interactions were diverse and that rural people would have played a crucial role in shaping the city, its territory, and its social organization. After briefly presenting the site of La Joyanca, we focus on its location as a relatively dense settlement within the region in order to target the discussion on its relationships with hinterland people and on its supposed “rurality.”

THE SITE OF LA JOYANCA: CULTURAL AND ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

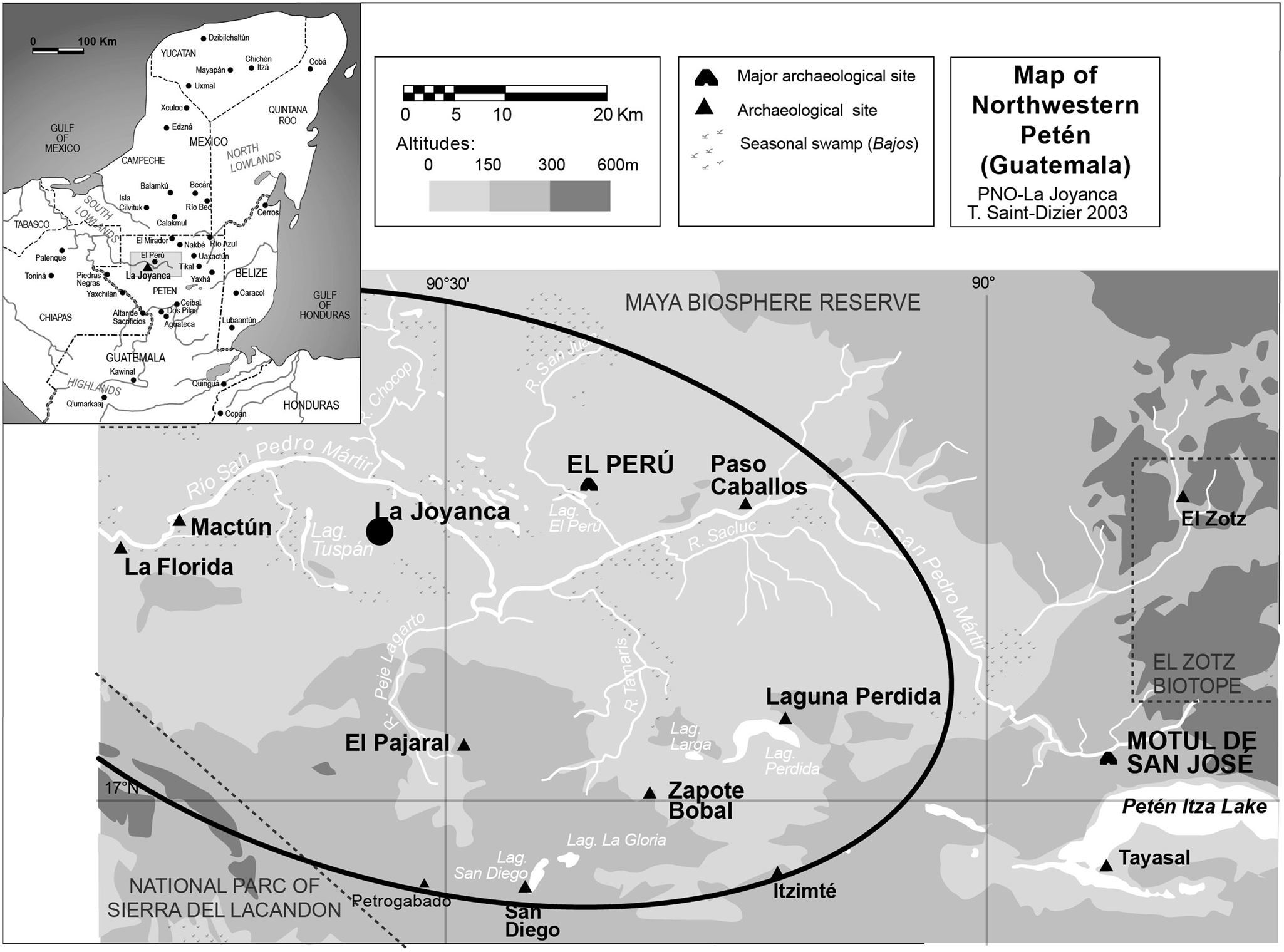

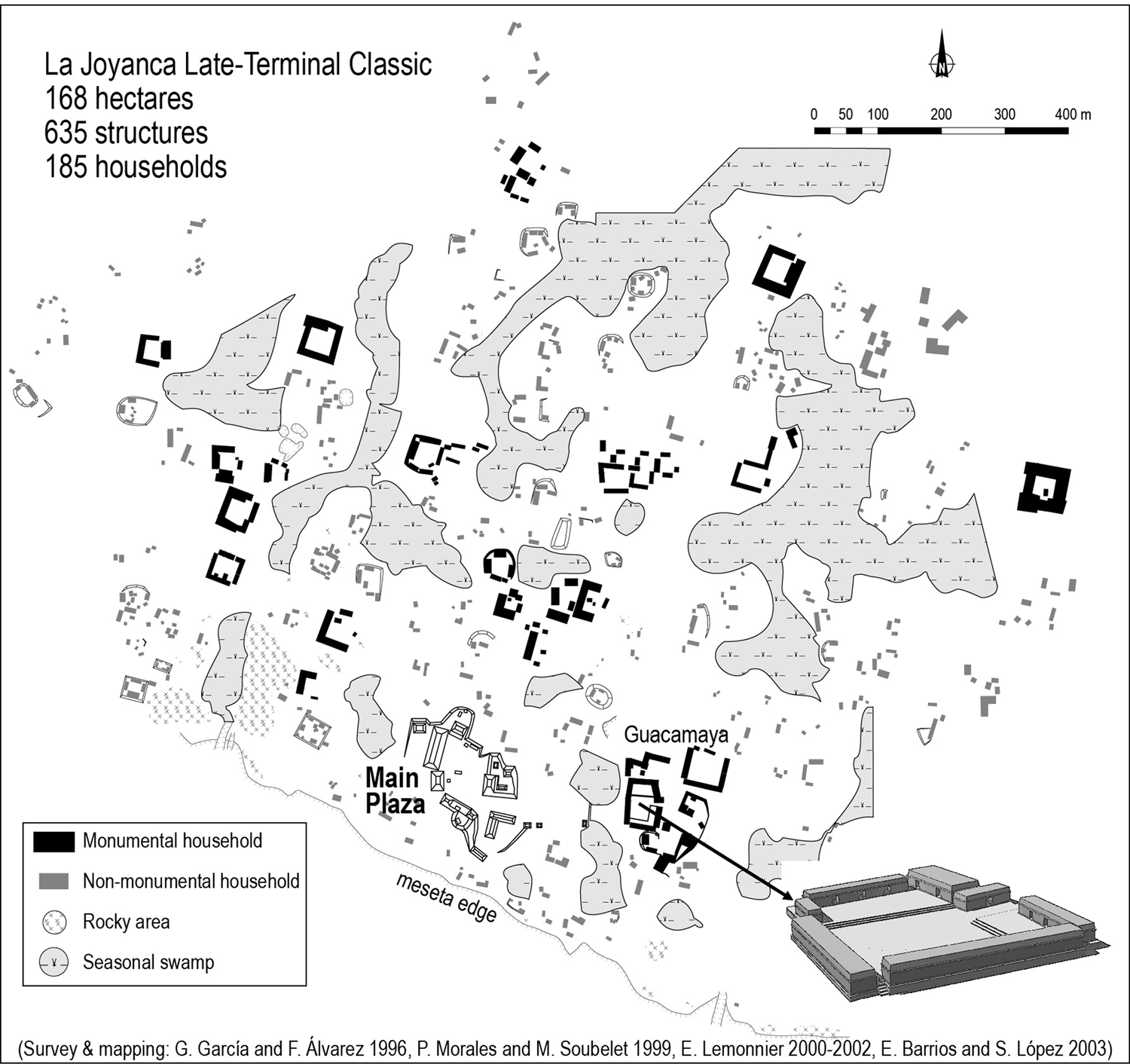

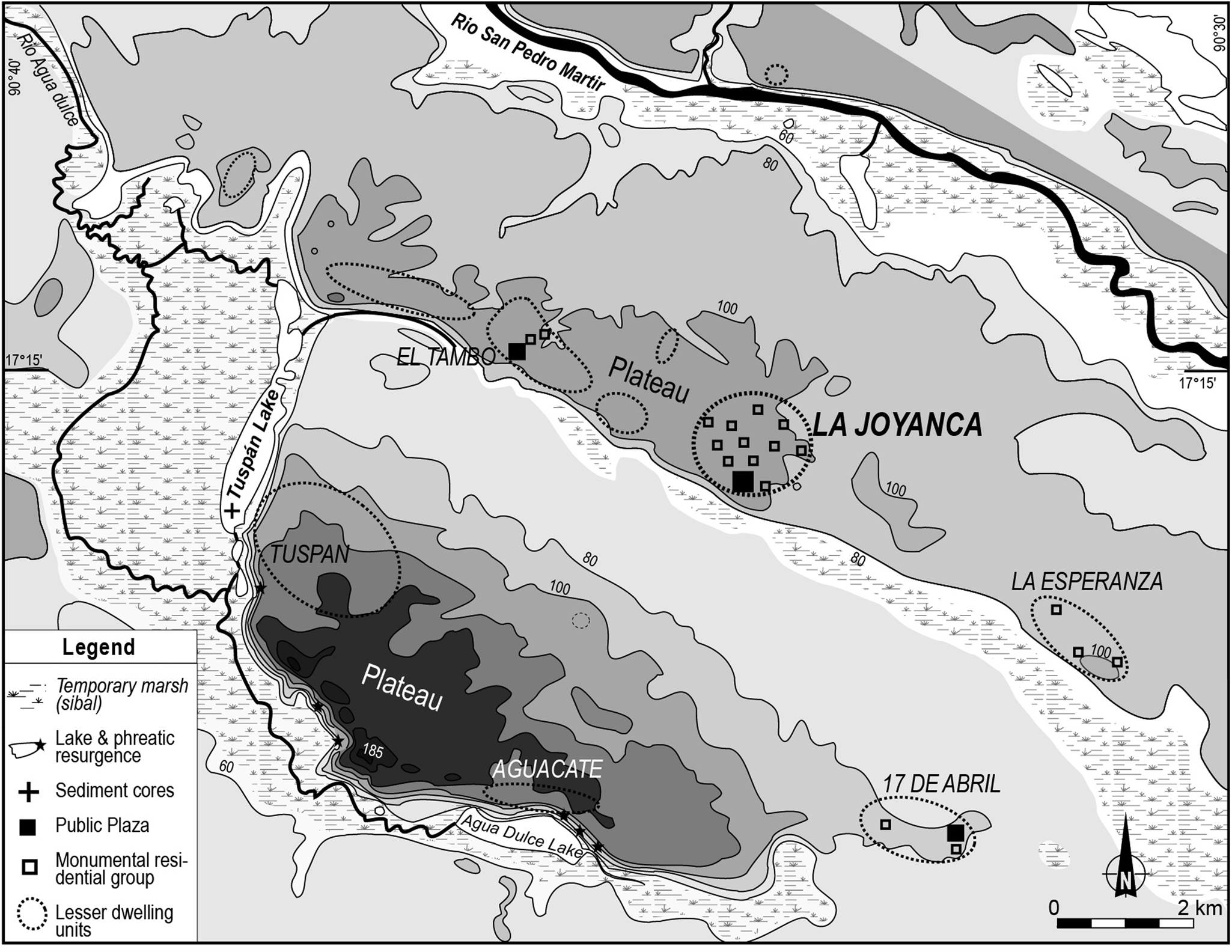

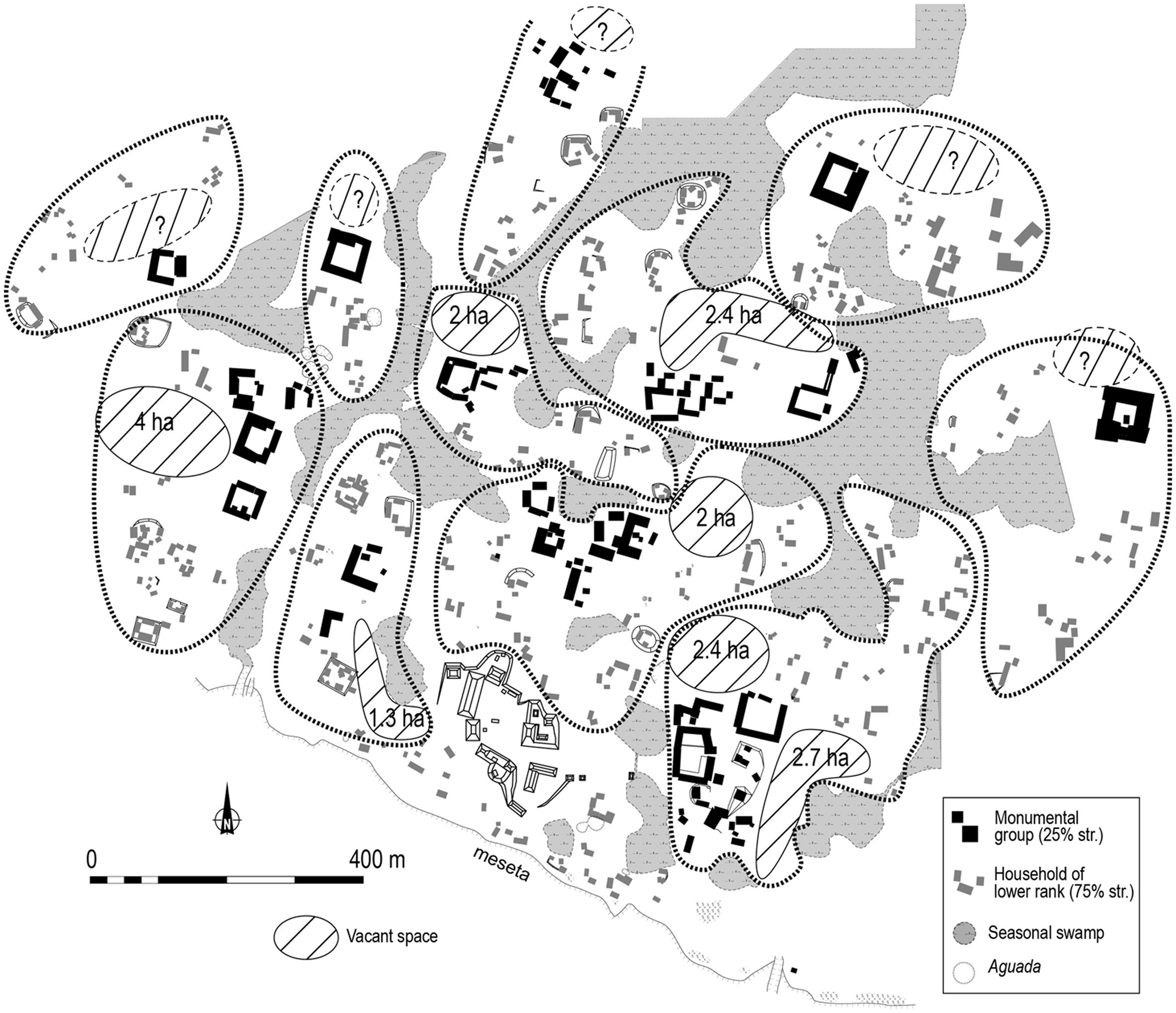

La Joyanca was discovered in 1994 in northwestern Peten, 20–25 km from larger contemporary sites El Peru-Waka’ to the east, and La Florida, El Pajaral, and Zapote Bobal to the west and south (Figure 1). It can then be considered a middle-rank settlement within the regional settlement hierarchy. At its peak during the Late Classic and early Terminal Classic periods (a.d. 600–900), the site covered almost two km2, and comprised a main plaza— the political and religious center with two, 12 m-high temple-pyramids and a long hall—a royal residential compound with one stela bearing inscriptions and several altars, and several monumental groups dispersed over a large residential area (Figure 2). Its chronological sequence goes back to the Middle Preclassic period (about 800 b.c.) when the village took form and then grew into a small city that was gradually abandoned at the end of the Classic period (between a.d. 950 and 1050; Forné Reference Forné2006).

Figure 1. Map of Northwestern Petén with location of La Joyanca. Modified from Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:inside cover).

Figure 2. Map of La Joyanca during the Late Classic period (a.d. 600–850). Modified from Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:47).

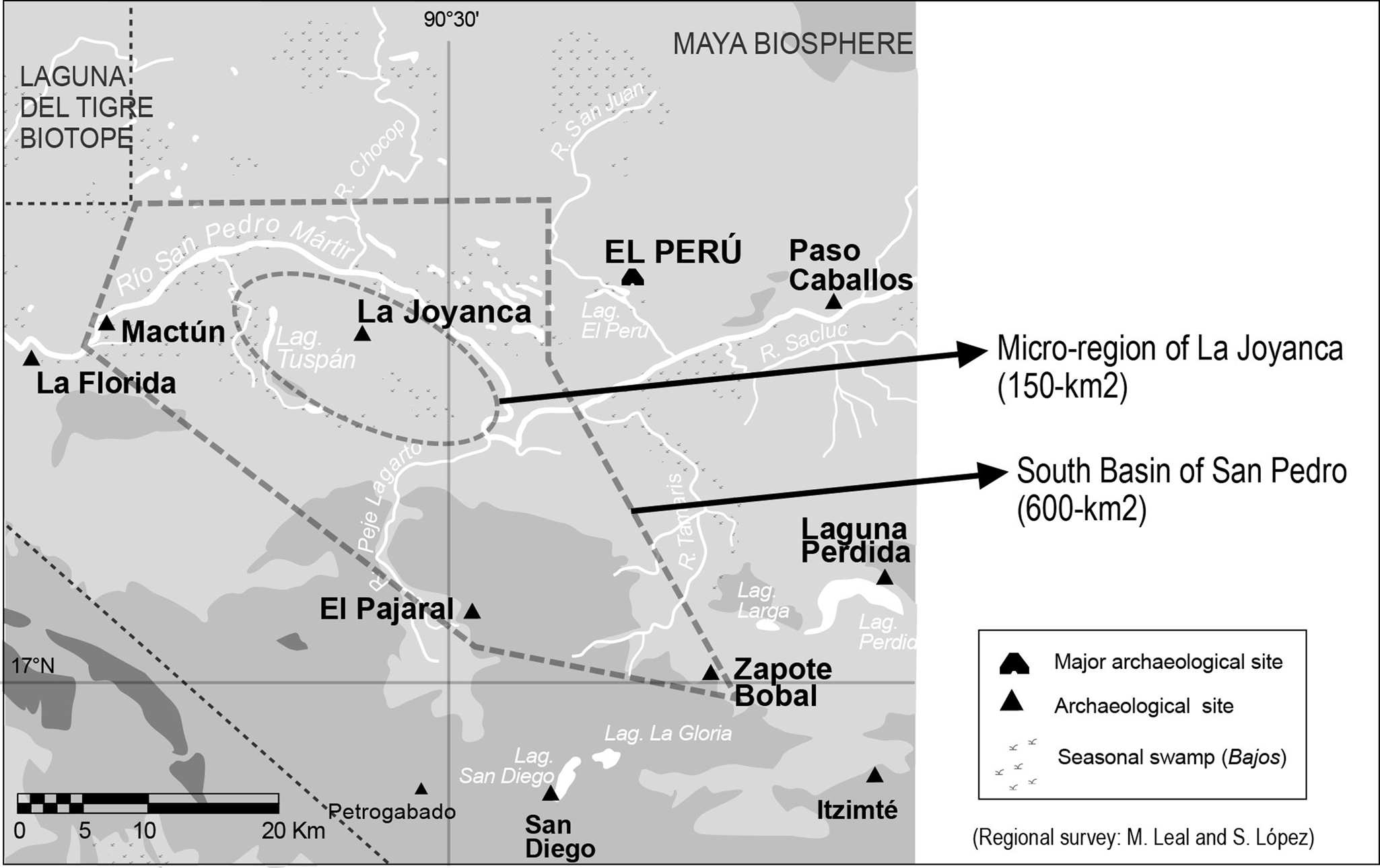

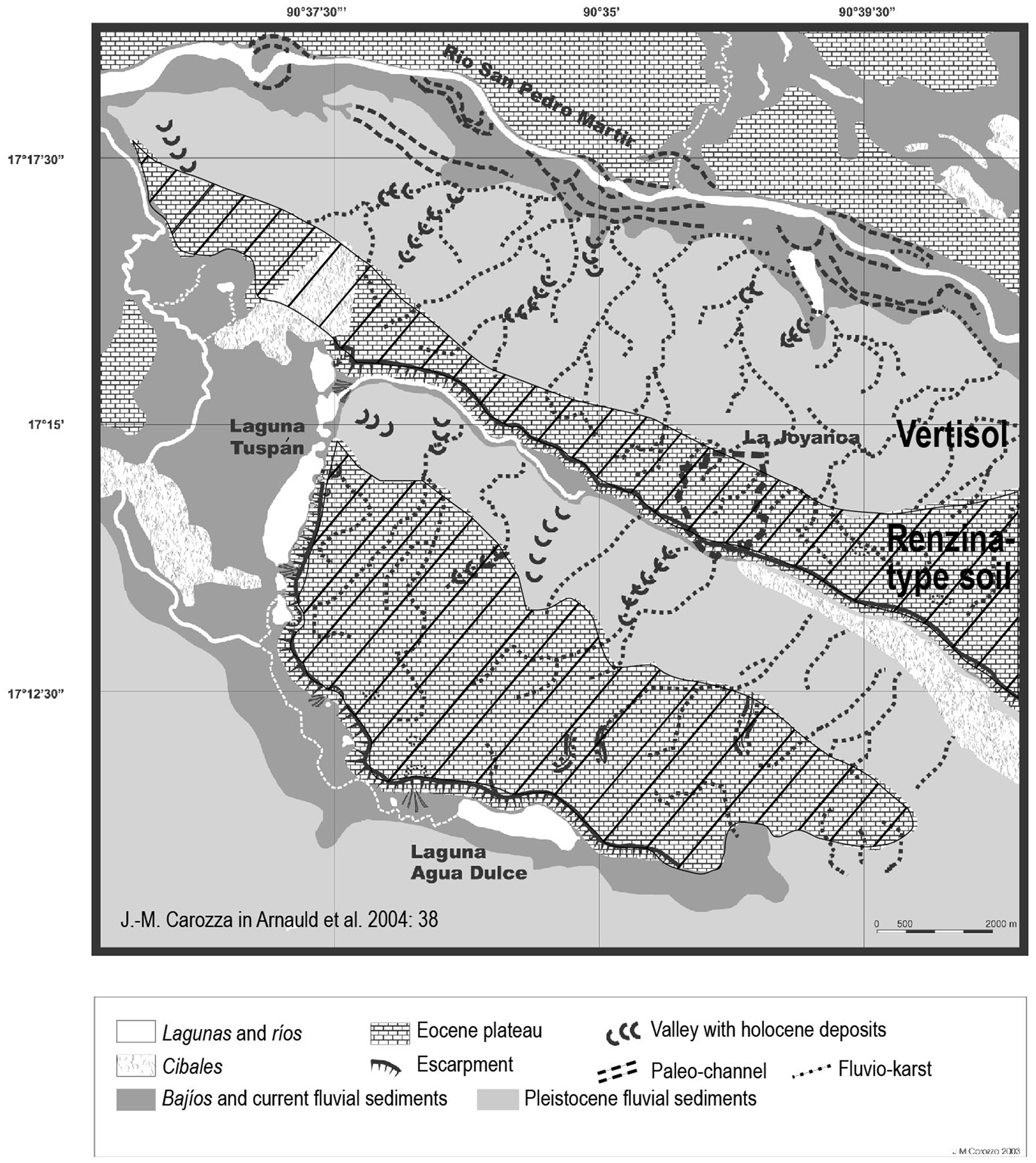

Based on the economic and sociopolitical organization of the site reconstructed in its local and regional context (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a; Lemonnier and Arnauld Reference Lemonnier, Arnauld, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2008), the more recent research compared the archaeological sequence to the paleoenvironmental sequence obtained from the proximate Lake Tuspan (Carozza et al. Reference Carozza, Galop, Métailié, Vannière, Bossuet, Monna, López-Saez, Arnauld, Breuil, Forné and Lemonnier2007; Galop et al. Reference Galop, Lemonnier, Carozza, Métailié, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004) and carried out specific test excavations to detect and date regional population movements responsible for urbanization and de-urbanization of the city between a.d. 550 and 950 (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017; Fleury et al. Reference Fleury, Malaizé, Giraudeau, Galop, Bout-Roumazeilles, Martinez, Charlie, Carbonel and Arnauld2014). While starting the early research, to explore the La Joyanca regional context, two study areas were selected on the basis of available archaeological data and local geomorphology: (1) a microregion of 150 km2 encompassing two limestone plateaus, or mesetas, bounded by rivers and wetlands—the San Pedro Mártir river to the north, lakes and swamps to the west, south, and east; and (2) a larger area of 600 km2 determined by the location of the largest and well-known sites (Figure 3). Both areas were surveyed with less accuracy than the fully forested La Joyanca site (two km2) mapped through intensive, systematic, pedestrian surveys (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:132–133; Lemonnier and Michelet Reference Lemonnier, Michelet, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2004). The main goal was to fill an archaeological gap in the south basin of the San Pedro Mártir River, and to document the hierarchized settlement system in which La Joyanca was inscribed. The 600-km2 survey was conducted with local informants along opportunistic transects across forested and cleared areas to locate and describe sites to establish a preliminary typology (Leal and López Reference Leal, López A., Escobedo and Laporte2000; López and Leal Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Arnauld, Ponciano A. and Breuil-Martínez2000, Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Breuil-Martínez, Ponciano A. and Arnauld2001, Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Breuil-Martínez, López and Saint-Dizier2002). In contrast, the 150-km2 microregion survey was more intensive on systematic transects (e.g., 5 x 1 km on the La Joyanca meseta) in the difficult context of a pioneer front of farmers currently colonizing the sector (Lemonnier and Ponciano Reference Lemonnier, Ponciano A., Arnauld, Ponciano A. and Lemonnier2012). During the recent fieldwork a small stretch of the Tuspan meseta was again intensively surveyed (see section Comparing Urban and Rural Settlement Pattern and Architecture; Lemonnier and Ponciano Reference Lemonnier, Ponciano A., Arnauld, Ponciano A. and Lemonnier2012). All in all, the 150-km2 microregion revealed 300 structures (118 on the 10-km2 La Joyanca meseta and 98 on the 20-km2 Tuspan meseta) clustered in 14 small sites and 40 isolated residential groups, some of them with relatively monumental structures (Lemmonnier and Ponciano Reference Lemonnier, Ponciano A., Arnauld, Ponciano A. and Lemonnier2012). Whereas the 600-km2 survey cannot be said to be exhaustive, the successive surveys carried out on the 150-km2 microregion spotted a large majority of mound groups in existence, although a few land properties were not accessible. We proceed to briefly describe the most relevant features of the latter microregional settlement system in which La Joyanca is by far the largest settlement.

Figure 3. Regional surveys within two study areas. Modified from Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:inside cover)

DEFINING THE HINTERLAND OF THE LA JOYANCA CENTER

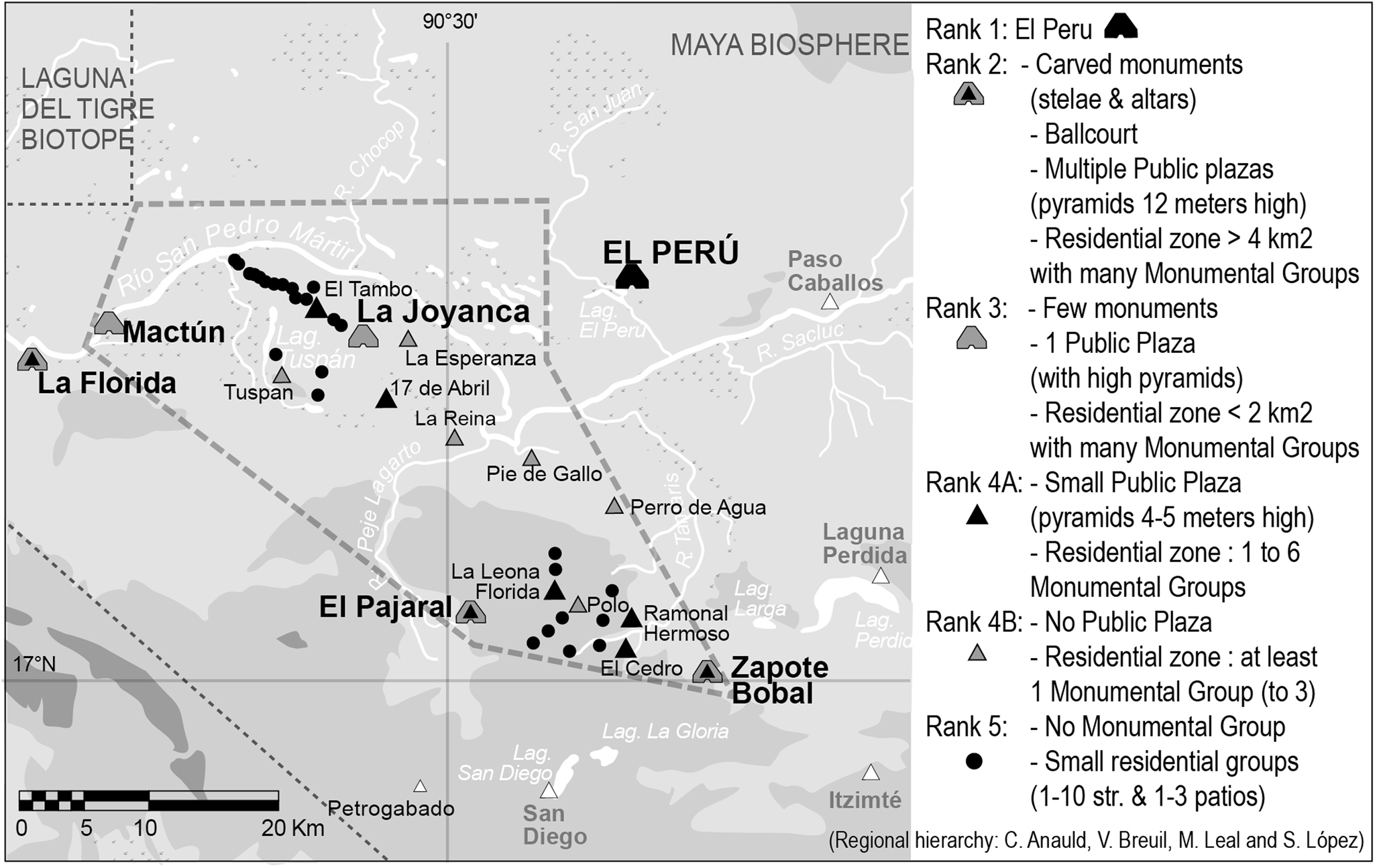

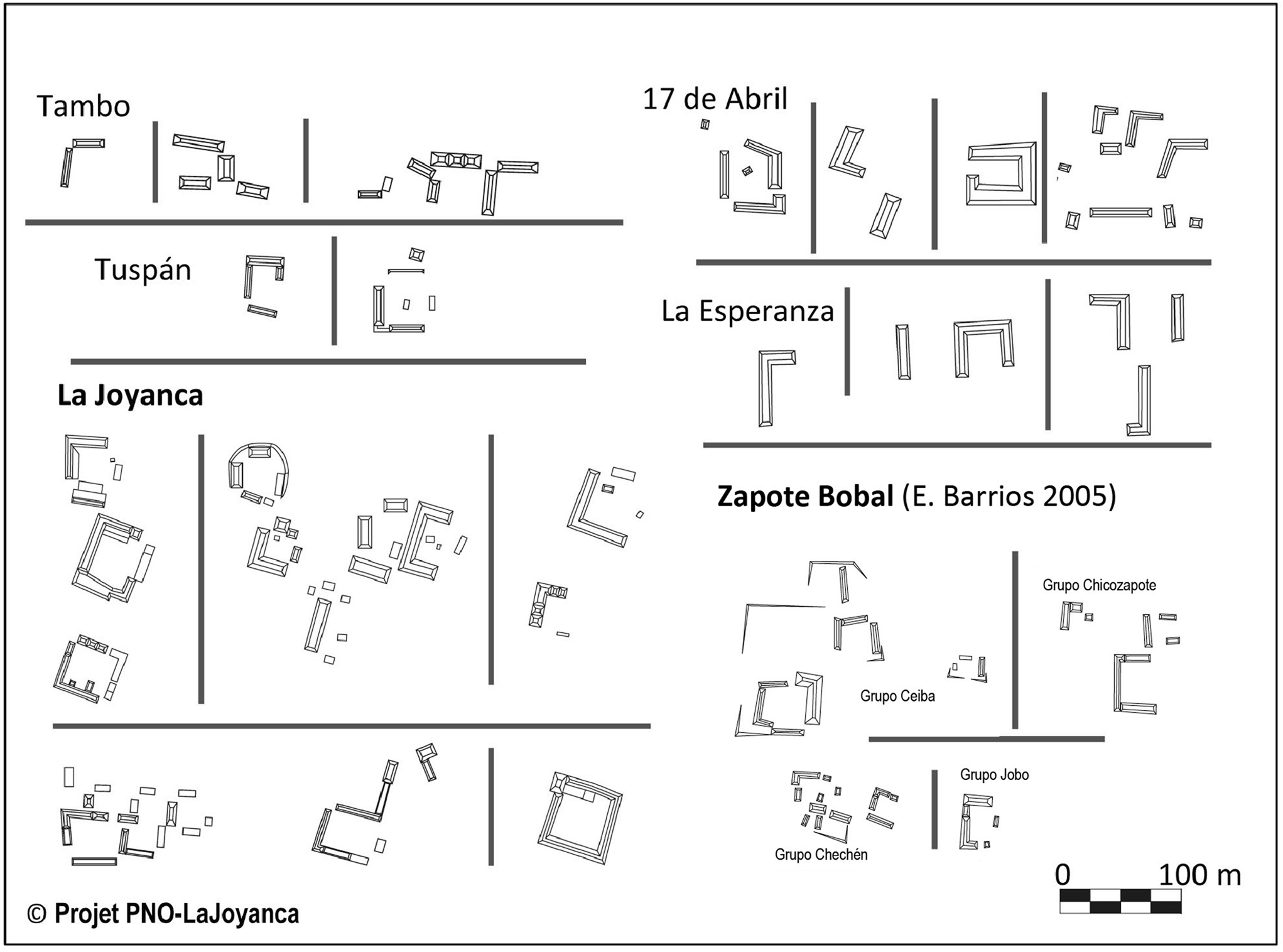

First, on the scale of the northwestern Peten, the hierarchy of sites is based on the usual criteria of size and structure number, and also on presence/absence of monumental residential groups that seem to have structured and characterized the settlements of the region (Figure 4; Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Forné and Lemonnier2004b, Reference Arnauld, Métailié, Breuil-Martínez, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004c, Reference Arnauld, Forné, Gámez, Barrios, Fitzsimmons, Lemonnier, Arroyo, Aragón and Mejía2012; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:103–108). Obviously, none of those settlements matches the size of El Peru-Waka’, the rank 1 site of the region. Rank 2 sites include the secondary centers of La Florida, El Pajaral, and Zapote Bobal, all with a substantial number of stone carved monuments (stelae and altars; Stuart Reference Stuart2003), one ballcourt, multiple plazas with pyramids 12-m high, and residential areas that cover more than four km2 and include many monumental residential groups. Rank 3 sites, La Joyanca and Mactun, have a single public plaza, a few carved monuments, and a smaller residential area with several monumental groups. These rank 1 to 3 sites show long occupational sequences that, with the exception of Mactún (dated Early Classic), reached their peak during the Late Classic and early Terminal Classic periods, and all seem to have been gradually deserted. Located in between these “largest” cities, the 11 sites of rank 4 are small, although comprising at least one monumental group. The sites of rank 5 are more numerous and correspond to small, usually isolated, residential groups devoid of monumental or vaulted architecture. Based on morphology and associated ceramics most rank 4–5 sites would have been occupied during the Late Classic period, with a few having earlier and later occupations dating to the Preclassic (La Tortuga, Meseta Tambo, and La Esperanza), the Early Classic (La Reina, Polo, 17 de Abril, and El Aguacate) and the Terminal Classic periods (Meseta Tambo and 17 de Abril; Forné Reference Forné2006; López and Leal Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Arnauld, Ponciano A. and Breuil-Martínez2000, Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Breuil-Martínez, Ponciano A. and Arnauld2001, Reference López Aguilar, Rodas, Breuil-Martínez, López and Saint-Dizier2002).

Figure 4. The regional hierarchy in the south basin of San Pedro Mártir. Modified from Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:inside cover).

This overall regional hierarchy confirms the political boundaries of the La Joyanca microregion, as this center appears located 20–25 km from the largest contemporary sites (ranks 1–2), and surrounded by lower-ranked sites (ranks 4–5) within a radius of five km. Notably, epigraphic data indicate that La Joyanca was endowed with a royal dynasty and by the end of the fifth century, part of a major political entity, Hixwitz or Hiix Witz, which extended to the south of the San Pedro River with El Pajaral and Zapote Bobal as the main centers, both with vigorous development between a.d. 450 and 780 (Breuil-Martínez et al. Reference Breuil-Martínez and Gámez2004a, Reference Breuil-Martínez, Gámez, Fitzsimmons, Métailié, Barrios and Román2004b, Reference Breuil-Martínez, Fitzsimmons, Gámez, Barrios, Román, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2005; Fitzsimmons Reference Fitzsimmons, Marken and Fitzsimmons2015; Forné Reference Forné2007; Gámez Reference Gámez2005; Stuart Reference Stuart2003). Therefore, on the microregional scale La Joyanca appears as a small, urban center in a hinterland spatially defined by rivers and wetlands and made up of villages (rank-4 sites) and farmsteads (rank-5 sites). Both categories of villages and farmsteads together form what we considered hinterland settlements. We acknowledge that a number of probably non-mounded, or low-mounded clusters of commoner household units associated with or isolated from villages and farmsteads, escaped our attention in pedestrian surveys.

Following methodological prerequisite (1), such are the proposed datasets that support a multiplicity of relationships among populations living in “rural and urban” spaces with diffuse limits. To reveal those relations, we now further detail settlement patterns and associated residential architecture.

COMPARING URBAN AND RURAL SETTLEMENT PATTERN AND ARCHITECTURE

Within the hinterland of La Joyanca, villages and farmsteads (sites of rank 4 and 5, respectively) are located on the highest parts of the two southeast/northwest-oriented mesetas that dominate lakes and wetlands (Figure 5). On the La Joyanca meseta the rank-4 El Tambo and La Esperanza sites are on flat uplands on either side of La Joyanca. They are clearly separated from this center by a break in residential density, as no farmstead has been identified to the east in between La Joyanca and La Esperanza. To the west, seven small (one- to two-structure) groups are scattered between La Joyanca and El Tambo. These rank-4 sites have vaulted architecture comparable to La Joyanca, but only El Tambo includes a public plaza with pyramids (Rank 4A versus Rank 4B for La Esperanza; Figure 4). Distances between household groups in both sites are greater than within La Joyanca: they are located 200–300 m apart, compared to 20–60 m at La Joyanca. The same distances also separate the rank-5 sites that form a continuous network of households to the northwest of El Tambo. South of the La Joyanca meseta on the Tuspan meseta the two rank-4 sites, Tuspan and 17 de Abril, are also located at the western and eastern ends of the plateau, whereas the center of the meseta has small rank-5 groups located 250–300 m apart. Similar to El Tambo, 17 de Abril (rank 4A) has a public plaza associated with monumental residential groups that are 50–80 m apart. To be noted, only a few groups of the Tuspan site (rank 4B) fall within the smaller range of distances separating groups within La Joyanca (we will turn to this exception presently). As expected in the La Joyanca hinterland, the settlement pattern is clearly much more dispersed than within the city. La Joyanca is a nucleated settlement while the rank-4 sites correspond to scattered villages with sparse groups. But one must note that the overall settlement pattern presents a mirror effect between both plateaus (symmetrical spatial distribution with probable sociopolitical meaning) and in architecture with components of rank-4 sites similar to those of La Joyanca, particularly residential buildings—all features that produce series of data useful to approach urban/rural relationships.

Figure 5. Map of the La Joyanca microregion. Modified from Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:43).

As mentioned, one of the main features of northwestern Peten settlement patterns is the frequent occurrence of isolated or clustered compounds including one or several patios with long multi-room vaulted residences. As seen, the rank-4 sites are defined by the presence of such monumental groups, which also characterize the higher-rank sites like La Joyanca or Zapote Bobal (Figure 6). At La Joyanca the extensive excavations of two of these monumental groups have shown the remains of finely-built vaulted palaces that formed at least one large patio covering 1000 m2 (Breuil et al. Reference Véronique, Lemonnier, Ponciano, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004c). A detailed study of their morphological characteristics and construction sequences suggests a high level of imitation and emulation between upper-status households (Arnauld Reference Arnauld2002; Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Forné and Lemonnier2004b). Interestingly, outside of La Joyanca on both mesetas few monumental groups are enclosed on their four sides creating true “quadrangles” (17 de Abril), corresponding instead to C- or L-shaped patios; but the groups are large with buildings more than 30 meters in length and two meters in height. The presence of such groups in these sites (to the exclusion of rank-5 sites) raises the question of a shared sense of sameness (and perhaps identity) as reflected by the technical and symbolic adoption (and replication) of specific construction, as well as orientation principles (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1991; Hendon Reference Hendon1991). To build vaulted residences outside the city within hinterland villages might have expressed a social affiliation with “urban” people (Magnoni et al. Reference Magnoni, Hutson and Dahlin2012; Robin Reference Robin2012; Yaeger Reference Yaeger, Canuto and Yaeger2000) almost as much as with local “rural” people. This, in turn, must be analyzed in relation to the neighborhoods of the city.

Figure 6. Plan of the monumental groups of the La Joyanca microregion (Projet PNO-La Joyanca) and Zapote Bobal (modified from Barrios Reference Barrios and Gámez2005:Figures 9.3, 9.4, 9.6)

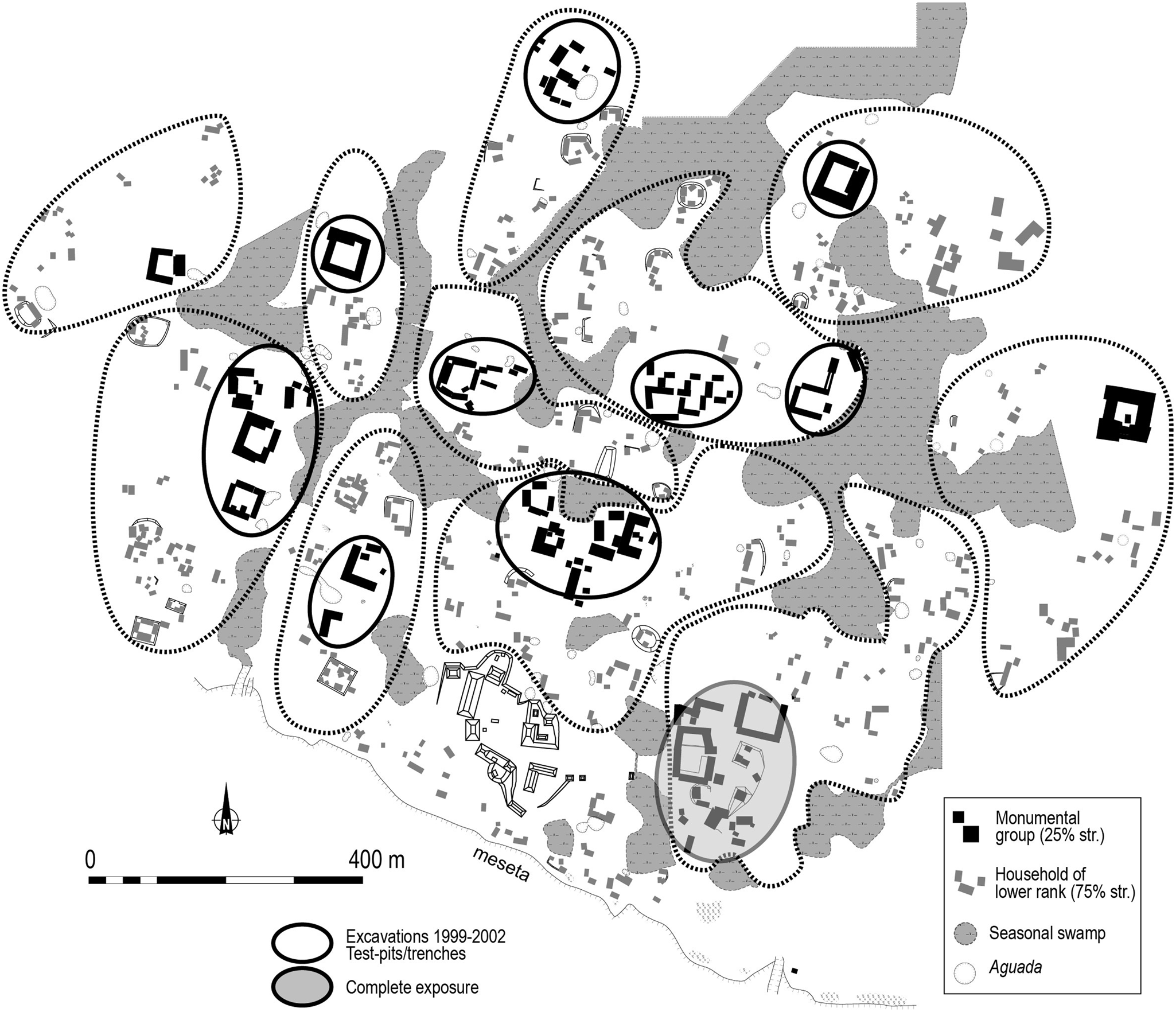

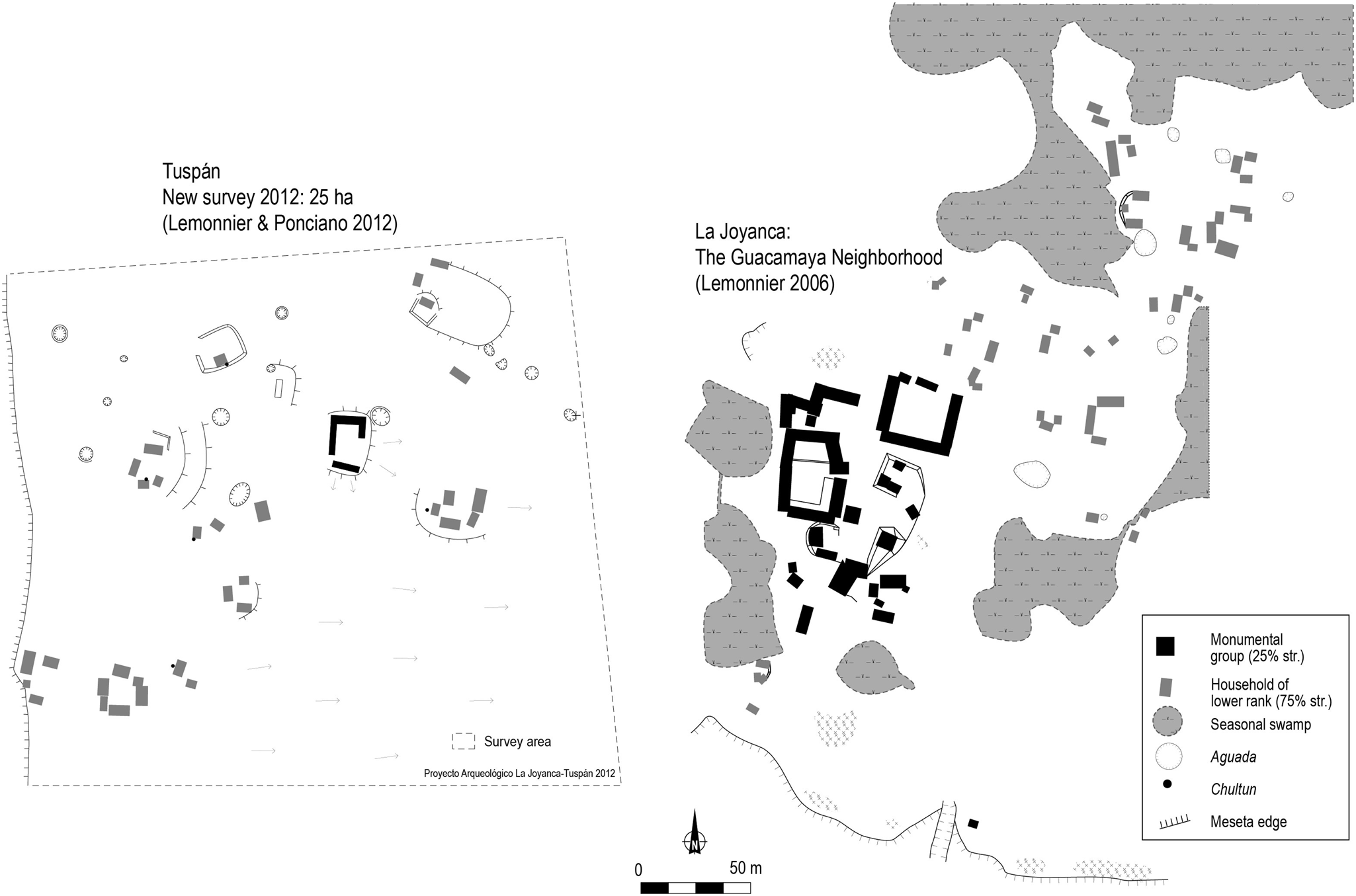

The La Joyanca neighborhoods are defined by one monumental residential group associated with several lower-ranked households and delineated by seasonal swamps and vacant spaces (Figure 7; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier, Arnauld, Manzanilla and Smith2012). The monumental groups of La Joyanca are interpreted as the residences of neighborhood leaders on the basis of morphological and spatial analyses (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009). Chronologically, a test-pit program revealed that the 10 to 11 neighborhoods developed from the beginning of the Late Classic to the Terminal Classic periods (from a.d. 600 to 900; Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Métailié, Breuil-Martínez, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004c). None of the hinterland vaulted compounds are precisely dated but all must postdate a.d. 600 and a ceramic surface collection done around the La Esperanza groups indicates a Late or Terminal Classic occupation. As mentioned, an additional survey in a sector of the Tuspan meseta was completed in 2012 and revealed a specific settlement pattern (Figure 8). There we mapped a concentration made up of only one, large vaulted-building patio surrounded by 12 small households located 30 to 60 m apart covering an area of 18 hectares (25 hectares surveyed). This layout is typical of the settlement within La Joyanca. It is tempting to interpret it as a “rural neighborhood,” as suggested for others Classic sites (for example in the Copan valley; Fash Reference Fash, Leventhal and Kolata1983; Freter Reference Freter2004; Webster et al. Reference Webster, Freter and Gonlin2000:183). Whatever label we adopt, clearly those similar compounds that exist within La Joyanca and also at a distance, at least in one case with a similar density of associated lesser groups, designate some sort of strong link uniting urban and rural people in their practical daily life. Following prerequisite (2), we can now tackle the issue of activities and interactions which can be surmised to have articulated urban/rural people and spaces.

Figure 7. The neighborhoods of La Joyanca. Modified from Lemonnier (Reference Lemonnier2009:Figure 7.16).

Figure 8. Comparison between the neighborhoods of Tuspan and La Joyanca. Modified from Lemonnier (Reference Lemonnier2009:Figure 7.16) and Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Forné, Gámez, Barrios, Fitzsimmons, Lemonnier, Arroyo, Aragón and Mejía2012:Figure 70).

LAND USE: THE NECESSARY CLOSE LINK BETWEEN URBAN AND RURAL POPULATION

The landscape we just schematized can be said to be pre-LiDAR. Recent LiDAR images that now cover hinterlands of several cities confirm the concept of “agrarian cities” (Arnauld Reference Arnauld, Guadalupe Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008; Arnauld and Michelet Reference Arnauld and Michelet2004; Dunning Reference Dunning1989) or “tropical low-density urbanism” (Isendahl and Smith Reference Isendahl and Smith2013; Lucero et al. Reference Lucero, Fletcher and Coningham2015) in which agrarian features not only extend on rural territories but were also entangled into the urban fabric. In other words, Classic agriculture was practiced within city residential zones, and outside in surrounding areas (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Hernández, Beach, Carr, Griffin, Jones, Lentz, Luzzadder-Beach, Reese-Taylor and Šprajc2018), i.e., in the peripheral zone and part of the rural zone. As far as agrarian investment is concerned, rural settlements had nothing to envy about urban settlements since many large-scale landscape modifications are still visible over hinterlands (Fedick Reference Fedick1994; Healy Reference Healy1982; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Lambert, Arnason and Hebda1983; Kunen Reference Kunen2004; Robin Reference Robin2013), modifying hydrology and soil formation among other parameters (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Hernández, Beach, Carr, Griffin, Jones, Lentz, Luzzadder-Beach, Reese-Taylor and Šprajc2018:17) as a result of the spatial and temporal magnitude of the agricultural management system and its sustainability (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Hernández, Beach, Carr, Griffin, Jones, Lentz, Luzzadder-Beach, Reese-Taylor and Šprajc2018; Fisher Reference Fisher2019). This agricultural infield/outfield system (Sanders Reference Sanders and Ashmore1981:362–364; Killion Reference Killion1990, Reference Killion1992) applied land-use practices to urban and rural settlements seen as a continuum, with farming intensity declining from residential zones to far fields, and from managed forest to “primeval chaos” (Dunning et al. [Reference Dunning, Beach and Luzzadder-Beach2012:3656], discussing the Maya notions of kax and kol; Killion et al. Reference Killion, Sabloff, Tourtellot and Dunning1989; McAnany Reference McAnany1995:68–70). Burning practices in swidden cultivation might have, nevertheless, introduced a relevant contrast since they were excluded from dense settlements for safety reasons. There is still much work to do before we can understand urban/rural articulation in agrarian organization in its variation and diversity over the lowlands during the Late Classic period. The few research efforts that attempted to correlate agricultural production and demography—two challenging tasks in archaeology—are unanimous in considering that production outside the city was indispensable to complement urban infield production (with or without complementary staple imports; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Beach, Luzzadder-Beach, Hixson, Hutson, Magnoni, Mansell and Mazeau2005; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:205–206; Liendo Stuardo Reference Liendo Stuardo2002; Webster et al. Reference Webster, Freter and Gonlin2000). How can this preliminary model help us envision the northwestern Peten hinterland settlements we just described? Did rural outfields and settlements provide urban La Joyanca with agricultural surplus?

La Joyanca is not different from many other Maya cities in that the site does not present surface visible agricultural features such as terraces, albarradas (plot enclosures), or rejolladas (e.g, such as those found at Caracol, La Milpa, Cobá, Chunchucmil, and Río Bec; Chase et al. Reference Chase, Chase, Weishampel, Drake, Shrestha, Clint Slatton, Awe and Carter2011; Estrada Belli and Tourtellot Reference Estrada Belli, Tourtellot, Laporte, Escobedo, de Suasnavar and Arroyo2000; Fletcher and Kintz Reference Fletcher, Kintz, Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983; Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Stanton, Magnoni, Terry and Craner2007; Lemonnier and Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013). Outside the city on the flat uplands of the mesetas soils are shallow (20–30 cm), but well-drained, fertile, and rich in organic matter. In seasonal and perennial swamps the lower-zone soils are deeper and clay saturated (Figure 9). Despite the potential of these different environments for building terraces or drained fields, none of these features has been identified through survey or analysis of aerial photography and satellite imagery studied by project geographers. As a signature, it remains that infield or urban agriculture (see Drennan Reference Drennan, Wilk and Ashmore1988) corresponds to permanent cultivation of gardens, orchards, and plots made perceptible by way of a negative feature or empty or vacant spaces, i.e., areas left open without visible architectural remains in the urban landscape (Killion et al. Reference Killion, Sabloff, Tourtellot and Dunning1989; McAnany Reference McAnany1995:65). Vacant spaces frequently represent 60–80 percent of the settlement total area (Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, Dore and Dunning1995). Several pedological, spatial, chemical, and ceramic analyses applied to such open spaces confirm a strong spatial correlation between the high-quality soils and the adjacent location of households (Dunning Reference Dunning1993; Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Beach and Rue1997; Fedick Reference Fedick1992; Killion et al. Reference Killion, Sabloff, Tourtellot and Dunning1989; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, Dore and Dunning1995). These authors discuss the size of vacant spaces as reflecting the degree of investment in infield strategies performed by different social levels from households to supra-households that produced staple crops while also maintaining garden plots (Fisher Reference Fisher2014; Isendahl Reference Isendahl2002). Based on the same argument, we suggest that there were infields within La Joyanca itself (Figure 10), i.e., plots that were cultivated in the vacant spaces. Their dimensions are appropriate (between 1.5 and 5 hectares), as are flatness (leveled ground), soil thickness (deep fertile soils), and proximity to monumental groups (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:184, 204–205, Reference Lemonnier, Kellett and Jones2016). The spatial association of elite (vaulted) residences and plots of land with best soils has been observed elsewhere, for example at Lubaantún (Hammond Reference Hammond1975), Oxkintok (Velásquez Morlet and López de la Rosa Reference Velásquez Morlet and López de la Rosa1992), Sayil (Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, Dore and Dunning1995), and Copan (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Freter and Gonlin2000). At La Joyanca, this same pattern means that (1) each neighborhood would have had some exclusive rights on a given extent of land, and (2) the monumental group of each neighborhood would have been the seat of a local socially- and economically powerful entity. Moreover, on the same basis, and judging by the very regular distribution of the lower-ranked households, smaller infields were located between the larger ones and also within every neighborhood seasonal swamp (Balzotti et al. Reference Balzotti, Webster, Murtha, Petersen, Burnett and Terry2013; Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Hernández, Beach, Carr, Griffin, Jones, Lentz, Luzzadder-Beach, Reese-Taylor and Šprajc2018).

Figure 9. Soil types in the La Joyanca microregion. Modified from Arnauld et al. (Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a:38).

Figure 10. The vacant spaces of La Joyanca (1-5 hectares) (modified from Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:Figure 7.10)

In the absence of positive features (terraces or albarradas), outfield agriculture is more problematic to document, even though palynological signatures have been obtained from sediment cores (Galop et al. Reference Galop, Lemonnier, Carozza, Métailié, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004). One of the sediment cores extracted from the Tuspan lake located five km from the city (Figure 5) suggests that milpa (swidden) agriculture was practiced in the microregion until the beginning of the Postclassic period, although at lower rates from a.d. 800 (Galop et al. Reference Galop, Lemonnier, Carozza, Métailié, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004; Carozza et al. Reference Carozza, Galop, Métailié, Vannière, Bossuet, Monna, López-Saez, Arnauld, Breuil, Forné and Lemonnier2007). Considering those milpa outfields were probably covering part of the La Joyanca city subsistence needs, we attempted to evaluate the population and agricultural production of urban La Joyanca during the apogee of the city (a.d. 850). The assessment suggests that at least half of the annual needs could have been supported by the production of outfield plots located on both mesetas (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:201–206, Reference Lemonnier, Kellett and Jones2016:178–181). One must admit that the La Joyanca hinterland would have partly fed the city. This simply points to the interactions which necessarily linked what we call “rural and urban” populations. This is where the compared evidence of the La Joyanca and Tuspan meseta neighborhoods would be interesting to investigate further, as it might open the array of activities and opportunities available to society at large in the La Joyanca landscape.

Now, more in line with methodological prerequisite (3), which proposes to explore a degree of symmetry between rural and urban patterns in spatial layout and occupation longevity, our additional approach addresses urbanization processes.

URBANIZATION AND SOCIAL DYNAMICS

With its royal neighborhood and 10 other such settlement units—each encompassing an elite family, lower-ranked families, and an agricultural domain—the spatial layout of La Joyanca resulted from an urban concentration that entangled political, social, and economic factors. Elite families were attracted by the local, though modest, royal court, whereas commoner families were attracted by elite families and the local availability of infield plots (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1992). Notwithstanding some of the supposed burdens of urban living such as health risks (see for example, Tiesler and Lopez Reference Tiesler and López Pérez2022), lower-status households—particularly rural people moving into urban settlements—probably found advantages in gathering around elite houses, benefitting from their affiliation through social identity, prestige, land, protection, and distribution networks. At La Joyanca, extensive excavations carried out at the modest two-houses Gavilán Group have showed that this small household located within the royal neighborhood had access to some “luxury” items also found in palaces, in particular scarce imported ceramic vessels (a Saxche-Palmar bowl and a Mataculebra plate; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:140, 147). Based on ethnographic, ethnohistoric, linguistic, and archaeological evidence, the social model of ancestor veneration and affiliation has local households and supra-households combining kinship (real or fictive) and coresidence under the aegis of the founding family, the latter controlling work force and lands inherited from locally buried ancestors considered as guardians and owners in an idiosyncratic land tenure system (Alexander Reference Alexander2000:391; Gillespie Reference Gillespie2000; Hendon Reference Hendon1991; McAnany Reference McAnany1995). This may have not differed from rural areas where ritual and agricultural practices made mobile households circulating on the same lands for generations (Robin Reference Robin2002; see also Pantoja Díaz et al. Reference Pantoja Diaz, Ancona Aragon, Gomez Coba and Gongora Aguilar2022). Non-swidden agricultural intensification would have fixed permanent residences and social groups to land. Migration processes are often mentioned to explain the cities' growth, especially between the Early and Late Classic periods. Nevertheless, few archaeological and isotopic analyses detect large scale movements. They tend to estimate the proportion of migrants below 20 percent at Copan and Tikal during the Classic period (Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Sharer, Buikstra, Wright, Traxler and Miller2010; Wright Reference Wright2012). Yet, they are still debated because of the ambiguity of strontium and oxygen signatures. Furthermore short-distance mobility is not detectable by these methods, even though farmers' mobility is acknowledged (Inomata Reference Inomata, Lohse and Valdez2004; Zetina Gutiérrez and Faust Reference Zetina Gutiérrez and Faust2011). Robin (Reference Robin2002) has provided an interesting discussion for intra-site mobility related to landscape constraints and management, and Hiquet (Reference Hiquet2020) contributes a quantified demonstration, through a population estimate and architectural energetics, of an exterior input of population into the city of Naachtun at the beginning of the Early Classic period.

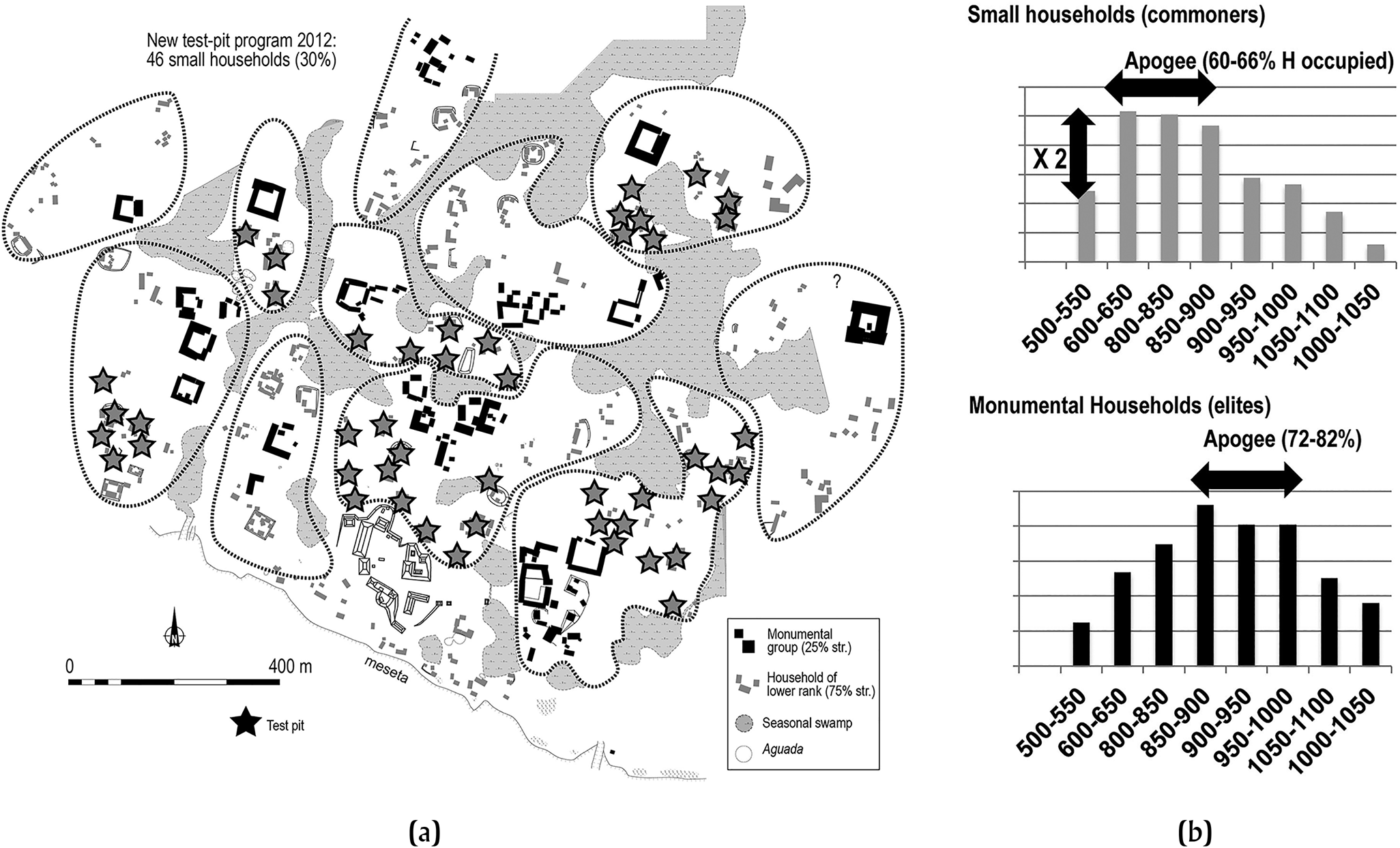

This is not the place to describe the La Joyanca research effort, which documented the Early-to-Late Classic population surge (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017), but a few words are in order since this case study represents an original way to tackle the rural/urban mobility issue. By means of several data sets, La Joyanca has been shown to illustrate the case of a city formed through time by processes of hierarchized social groupings and regular scattering over an agrarian landscape that probably integrated a mix of “urban” and “rural” populations. The 2012 test-pit program carried out in the La Joyanca neighborhoods was designed to test the hypothesis of population mobility from the hinterlands into the city at the beginning of the Late Classic period. This assumption had been formulated by 2003 based on the correlated archaeological and paleoenvironmental sequences indicating a co-occurrence of (1) the abandonment of agricultural activities on the Tuspan meseta inferred from changing conditions of erosion, and (2) the expansion of La Joyanca characterized by the construction of monumental residential groups (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Alvarado2004a; Galop et al. Reference Galop, Lemonnier, Carozza, Métailié, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004). Results from the tested sample of La Joyanca's small household groups (representing 30 percent, located throughout six neighborhoods) revealed that they doubled in number over a short time span, a.d. 500–550 to 600–650 (Figure 11; Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017, Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Michelet, Forné, Arnauld, Beekman and Pereira2021). This same Early to Late Classic time span marks the beginning of the demographic apogee in the city, while the paleoenvironmental studies indicate an early abandonment of intensive maize cultivation and regrowth of upland forest on the Tuspan meseta (Fleury et al. Reference Fleury, Malaizé, Giraudeau, Galop, Bout-Roumazeilles, Martinez, Charlie, Carbonel and Arnauld2014; Galop et al. Reference Galop, Lemonnier, Carozza, Métailié, Arnauld, Breuil-Martínez and Ponciano2004). This does not preclude a continuous, much less intensive swidden cultivation of this upland forest. La Joyanca monumental groups generally show earlier foundation and more longevity than low-rank dwellings, making plausible that urban elites attracted some hinterland population. The latter would have migrated into the settlement to expand the neighborhoods where they would have helped build the vaulted residences.

Figure 11. Program of test-pits carried out in five neighborhoods of La Joyanca (modified from Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017:Figure 5) and comparison of the chronological sequences between the small households and the monumental groups

An additional result of the same research are data about the number of small households that were abandoned early after the monumental groups were built and enlarged (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Forné, Sion and Alvarado2017:Figure 9, 29–30). This apparently reverse movement, a “contraction” process, may reflect that some low-rank households integrated into the enlarged elite compounds (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Michelet and Nondédéo2013) whereas others were expelled from the urban neighborhoods, then returned to their hinterland place and resumed new cycles of mobility. The latter move would then explain the presence of the morphologically Late-Terminal Classic neighborhood identified on the highest level of the Tuspan meseta. This is relatively speculative: we do not have archaeological data to infer the nature of the socioeconomic relationships that might have existed in late times between urban residents and supposed counterparts settled outside of the city on the Tuspan meseta (see Rice [Reference Rice, Wilk and Ashmore1988:241] for analogous intents in specifying social relations). What we can say is that, like those in the city, this late Tuspan neighborhood would have had residents able to invest into a strong agrarian component which consisted not only of substantial vacant areas, but also of numerous large ancient aguadas that we were surprised to discover on the Tuspan meseta in such close proximity with the lake (Figure 8). Even though a LiDAR survey and excavations are badly needed to clarify the relations of this particular hinterland sector with La Joyanca late in their respective sequences, it is nevertheless of interest to tentatively stress that land use modifications in and out of urban contexts may have been narrowly coordinated.

DISCUSSION

The evidence from multiscalar settlement pattern explorations in the La Joyanca entity, along with the specific interpretations we have been able to make about land use within urban contexts (La Joyanca neighborhoods) and rural landscapes (hinterland settlement system), both help us sketch some of the activities and interactions that linked together urban and rural populations. Additionally, reconstructing the urbanization/de-urbanization processes further confirms that those interactions must have been intense enough to support some high degree of social congregation in the city, yet they may have resulted in partial desertion of urban neighborhoods and even perhaps formation of rural neighborhoods. This may be considered a tentative model of symmetrical urban/rural dynamics that we still poorly conceptualize socially, spatially, and temporally.

There is no doubt that rural people, commoners and elites alike, took an active part in the layout and lifeways of hamlet-village systems and cities. But how concretely producers who settled within the city developing infields succeeded in maintaining their outfields remains difficult to understand. The same people may have moved periodically from rural to urban contexts and vice versa, or the same social groups may have regularly relocated their members in corresponding rural and urban residential compounds. Total or partial overlap, or complete distinction of populations, cannot be discarded on the basis of the present evidence. The 2012 research in the La Joyanca and Tuspan meseta shows that commoners did settle in urban neighborhoods during the Late Classic period, and that some of them soon integrated the growing elite compounds, and others left the city to re-settle in the hinterland. This movement suggests mechanisms of social integration and dissolution that left people with a degree of freedom on the agrarian level. The unexpected city-hinterland symmetry in residential architecture and neighborhood layout (e.g. vaulted-structure groups in La Joyanca and meseta villages) would have resulted from such movements across diffuse and porous boundaries. While socioeconomic subordination may have characterized elite/commoners relations, interdependence would better qualify rural/urban activities of both categories. Urban neighborhoods and their plausible rural counterparts would have formed coordinated working groups (see Alexander [Reference Alexander2000] and Wilk [Reference Wilk1988] for ethnohistoric and ethnographic examples), and their collaboration would have resulted in complex social relations articulated through land tenure and subsistence economy.

Without entering into the intricacies of people's movements (see Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Michelet, Forné, Arnauld, Beekman and Pereira2021), it is interesting to explore some circulations that might have reached a degree of stability. The hypothesis of “rural neighborhoods” that would have been socially, economically, and politically related to urban ones deserves to be investigated further. We are in need of robust chronologies bearing on architectural and agrarian components documented in urban and rural contexts. In lowland Maya archaeology, currently developed LiDAR surveys might well provide us with new evidence of hinterland agglomerations to which the notion of “rural neighborhoods” may fruitfully apply (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Lemonnier, Purdue, Hiquet, Castanet, Marken and Arnauld2022), being more specific than “rural communities.” We emphasize the similarity in layout and spatial separateness of those intermediate-scale settlement units located within, and off cities. Socially they still have to be interpreted as linked, although spatially separate, coresidential groups, whether considered as two-part Houses (sensu Lévi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1979; see Taschek and Ball [Reference Taschek and Ball2003] for Nohoch Ek and Canuto and Fash [Reference Canuto, Fash, Golden and Borgstede2004] for rural Copan), or considered as double-segment major lineages (Freter Reference Freter2004, Hendon Reference Hendon1991). These similarities open a perspective for furthering our understanding of urban/rural entanglement as they invite us to broaden our perception of neighborhoods to rurality beyond urbanity.

Another related hypothesis worth a brief heuristic discussion is that the specific processes involved in the planning not only of the city landscape but also of the hinterland landscapes were shared and articulated. Urban elite agency would have been among the critical factors producing hinterland sociopolitical dynamics, in good part associated with agrarian integration, and rural population should not be excluded when exploring the issue of city planning. Hence, while approaching complex urbanization/de-urbanization processes, the heuristic categories of urbanity and rurality (each in some way including elite and commoners) remain helpful to sketch the broad outlines of organizational models. As repeated in the present essay, however, the dichotomy has some meaning only if assessed as concretely as possible through the multiplicity of activities and interactions that the ancient people engaged in everyday life in/off the city. Household archaeology has brought remarkable datasets—the Chan project in particular (Robin Reference Robin2012, Reference Robin2013)—bearing on such an empirical assessment of rurality and urbanity seen through the lens of domestic contexts, assuming a degree of symmetry in the relations of “local communities” to their proximate “center” (Robin Reference Robin2012:12). Instead of throwing the baby (the dichotomy) out with the bath water, documenting activities is the best way to approach the Maya idiosyncratic concept of rurality against urbanity.

In this broad topic, archaeological heuristics of time inscribed in space are essential. Mobility characterizes not only pre-Hispanic but also historical and contemporary Maya societies (e.g., Farriss Reference Farriss1978). Datasets documenting longevity, continuity, and discontinuity of urban as well as rural housing facilities in city/hinterland planning have a crucial importance. Occupational hiatus in chrono-stratigraphic sequences are difficult to detect and non-detection should not mean continuity. Continuous series of construction-reconstruction layers can be excavated on structures a few meters away from colluvial deposits and paleosoil formation extent on outdoor spaces that rather suggest hiatus (Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier2009:Figure 5.1). In such cases, continuity can result from the action of the builders having scraped ruins before superimposing reconstruction; the lack of testing away from built spaces leads us to consider that mobility was lesser than it might really have been (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Michelet, Forné, Arnauld, Beekman and Pereira2021). Also, invisible structures (Culbert and Rice Reference Culbert and Rice1990:15; Johnston Reference Johnston2004) are to be explored both in urban vacant spaces and in rural universes as distinct configurations of early and late neighborhoods may have been superimposed sequentially in the same place through several periods of stability and mobility. Sequences of subfloor burials are another proxy of great promise to help reconstruct cycles of mobility since the generally low number of buried individuals in a Maya household group might be an effect of their mobility in life. This funerary practice (to bury under the house) must have something to do with a millenary practice of mobility (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Lemonnier, Michelet, Forné, Arnauld, Beekman and Pereira2021; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burhama, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzóne and Yonenobu2015).

Urban/rural studies are being revolutionized by unexpected collective features—water reservoirs, causeways, trails, marketplaces, and shared public spaces—now being discovered through LiDAR surveys. We should be prepared to interpret them in the context of community formation having developed in interaction with proximate urban settlements. Hopefully the functional diversity in built components and their various morphologies in rural landscapes will strengthen our premise of rural/urban symmetry and broaden our etic perception of elite and commoner agency across their landscapes. There is still much to be explored about the manners in which ancient people behaved together and distinctly within, and away from, large population concentrations.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

To summarize, several research efforts carried out within the small royal city of La Joyanca and its region (northwestern Peten) have brought up a large quantity of specific data bearing on the Classic Maya rural/urban interaction. The pre-LiDAR, multiscalar study of regional, microregional, and local settlement patterns allowed us to (1) hierarchize all surveyed settlements, cities, towns, and villages in a 600-km2 zone, (2) assign La Joyanca to the functional type of a medium-sized political capital overseeing a (roughly) 150-km2 hinterland structured by villages, hamlets, and farmsteads forming the microregional settlement system, and (3) to define a number of urban neighborhoods within the boundaries of the 2-km2 city.

Each of these neighborhoods were defined by, among other features, an elite monumental residence spatially associated with cultivable fertile land (vacant space) and clustered lesser housing units. Broad-scale archaeological, sedimentological, and palynological studies of land use not only within La Joyanca but also in the hinterland have been correlated with tentative quantifications of occupational longevity, demographic congregation in urban neighborhoods, and agricultural production. Here we have attempted to assess the subsistence needs of the urban population, and we have discussed their plausible multiple affiliations and movements within the microregion while attending their subsistence needs. We mainly raise the case of farming activities, but others as essential as hunting, fishing, trading. and socializing remain to be discussed.

As we propose that rurality and urbanity are notions that retain heuristic qualities even though the dichotomy does not correspond exactly to Maya emic conceptions, a provisional definition of rurality should be offered based on concrete activities developed by Classic Maya commoners and elite. In the La Joyanca entity, rurality meant a relatively isolated living, or at least a living in a small, low-density settlement, with perhaps less health risks than within the small city, somewhat more freedom in land use, technics, and crop management, and more frequent hunting (hence more meat consumption). Carrying crops from outfields should have been one of the most felt constraints—one that might have induced temporary moves so as to live where the staples were available. Decisions about place and time of consumption, however, certainly also depended on a desire of participating in exchanges in the marketplace (e.g., selling surplus) and within the social neighborhood (e.g., providing food in feasting occasions). Rurality supposed complex negotiations among individuals and groups to attend to social and political obligations (feasting, ceremonies, ritualism, religious participation, and others) in appropriate time/space. Contradictory requirements certainly arose in societies with no transportation technology other than walking and canoeing. Settlements must preserve the trace of those tensions and this is what should be retrieved archaeologically.

RESUMEN

Considerando las tierras bajas mayas del clásico como un paisaje complejo articulando series de asentamientos jerarquizados en medio de tierras agrícolas, la definición de lo urbano y de lo rural sigue abierta y en proceso de debate. Al fomentar estudios detallados sobre las relaciones entre la población de ambas categorías, se podría acercarse mejor a lo que significaron urbanidad y ruralidad en las sociedades mayas antiguas (y tal vez alejarse de esta dicotomía). Análisis focalizados en la arquitectura residencial y en las dinámicas sociales internas a los asentamientos, sugieren que estas relaciones habrían rebasado el ámbito agro-económico. En base a los trabajos realizados en La Joyanca (Petén Noroeste, Guatemala), una pequeña ciudad rodeada por aldeas y caseríos, este artículo explora el tema de la ruralidad mediante tres parámetros: el uso del suelo, el patrón de asentamiento y la movilidad de la población. El objetivo es evaluar las relaciones entre este centro y su entorno rural para intentar refinar los conceptos empleados.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Céline Lamb for her invitation at the Society for American Archaeology symposium entitled “Reconceptualizing Rurality: Current Research in Ancient Maya Hinterlands” (Washington 2018) and for her help in improving the writing of this article. We also want to express our great gratitude to The Instituto de Anthropología e Historia de Guatemala for having authorized our successive research projects in northwestern Peten, and to those who supported and funded both projects, Mrs. Gilberte Beaux, Basic Holdings Ltd., Licenciado Rodolfo Sosa, Basic Resources International (Bahamas) Ltd. Sucursal Guatemala, the Perenco company, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. Several reviewers must be thanked for their constructive criticism, yet all errors remain ours.