In this paper we argue that the reproduction of specific mortuary practices, in the absence of centralized political control, indicates that broadly shared cosmologies of place were significant forces of social integration in the lower Ulúa Valley from as early as 700 b.c. to the fifteenth century a.d. We rely on a model of cosmology of place developed in previous research on sites dating between a.d. 450 and a.d. 850 (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2003, Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006, Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007). During this period, people in the lower Ulúa Valley oriented interment with respect to specific mountains and seasonal movement of the sun, including sunrise and sunset near the time of solstices. This resulted in alignments of extended burials skewed from cardinal directions but coordinated within a shared cosmology and geography.

Building on this previous work, we reviewed all available burial data from the valley for the Formative through the Late Postclassic periods. We identified an unexpectedly long history for previously described practices. By combining data from our own excavations with those from previously excavated sites, we have identified both long-term continuities and moments of change. Patterns observed in smaller numbers of burials from different sites become more visible in the resulting valley-wide sample.

In the Middle Formative period (700–200 b.c.), we see participation in a cycle of primary and secondary burial practices balancing commemoration of the person with familial or communal relationships. We have no burial data for the period from 200 b.c. to a.d. 450. In burials dating after a.d. 450, a de-emphasis on the individual person and a shift in the locus of communal participation in commemoration away from the mortuary setting itself take place. Burials continue to be placed in residential spaces, as they were previously. Extended position remains the norm, allowing continued alignment of burials with cosmologically significant directions. We can identify evidence of a cycle of secondary mortuary ceremony after a.d. 450 that is consistent with continued understanding of personhood as partible and relational (Lopiparo and Joyce Reference Lopiparo, Joyce and Miniaci2023), established in the Formative period.

In the transition to the Postclassic period, we see greater change. A new emphasis on seated position or “bundle” burial posture breaks with long-established patterns of orientating the bodies of the dead to shared points on the horizon. The new burial position is accompanied by a renewed practice of deposit of objects as part of burial, after centuries when this was not common. Objects included show that residents of the lower Ulúa Valley were participants in a regional network of ceremony, connected to sites in Yucatan. The individuality of the buried person was foregrounded by these new burial practices, which persisted until the end of the prehispanic period.

We conclude that throughout this long history, actions taken to commemorate and interact with the dead and to perpetuate social relations through time were one of the main forces integrating the heterarchical network of settlements in the lower Ulúa Valley. These afterlife cycles include the many ways that the inhabitants of the Ulúa Valley engaged in ongoing relationships with the dead, a kind of necrosociality that was essential to social reproduction. They constituted politics by other means, enabling coordination between neighboring communities that shared mortuary practices and beliefs while maintaining autonomy.

Research Background

The lower Ulúa Valley (Figure 1) is a 2,400 km2 valley formed by the Ulúa River and its tributaries, the largest of which was what today is the separate Chamelecón River. Research at sites along the Ulúa River from the 1890s through the 1930s documented deeply stratified deposits from the Middle Formative through the Postclassic periods (Gordon Reference Gordon1898b; Popenoe Reference Popenoe1934; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). Beginning in the 1970s, systematic survey identified over 500 sites and defined the changing geomorphology of the valley over its history (Henderson Reference Henderson1984, Reference Henderson1988; Pope Reference Pope1985). New ceramic typologies facilitated cross-dating of sites (Beaudry-Corbett et al. Reference Beaudry-Corbett, Caputi, Henderson, Joyce, Robinson, Wonderley, Henderson and Beaudry-Corbett1993), and substantial regional variation was documented (Joyce Reference Joyce1985; Robinson Reference Robinson1989). Recent studies of polychrome ceramics (Joyce Reference Joyce2017a) and figurines (Hendon et al. Reference Hendon, Joyce and Lopiparo2014) used in sites throughout the valley have refined the Classic period chronology and offered new proposals concerning Late Classic social dynamics (Joyce Reference Joyce2023).

Figure 1. Map of lower Ulúa Valley with site locations (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Most visible architecture dates to the Classic and Terminal Classic periods (ca. a.d. 550–950). Early exploration at one site with significant architecture, Travesía (Stone Reference Stone1941), has been complemented by more recent excavations (Joyce Reference Joyce and Robinson1987) and studies of marble craft production (Luke and Tykot Reference Luke and Tykot2007). Research on Cerro Palenque, a second center, demonstrated that it grew to be the largest site in the valley between a.d. 850 and a.d. 1050 (Hendon Reference Hendon2010; Joyce Reference Joyce1991). Currusté, a third center, initially explored in the late 1970s (Hasemann et al. Reference Hasemann, van Gerpen and Veliz1978), was the focus of later research documenting households and public ceremonies (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo2009). These projects were complemented by household archaeology in a series of sites with more modest architecture (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979; Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011; Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo1994, Reference Lopiparo2003; Swain Reference Swain1995).

We build on previous analyses by Jeanne Lopiparo of burials she encountered in sites in the central Ulúa floodplain (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2003). She places burials at these sites, occupied from the middle of the Classic through the Late and Terminal Classic periods (ca. a.d. 550–950), in the context of household production and the intergenerational reproduction of families through the practice of rituals that produced a variety of structured deposits (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006, Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007, Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021). At Currusté, Lopiparo documented contemporary primary and secondary mortuary rituals (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo2009).

We juxtapose Lopiparo's analyses of Classic period mortuary practices with information from Rosemary Joyce's investigation of museum collections and archival sources documenting earlier and later burials encountered in the early twentieth century in sites along the Ulúa River. A group of burials from Playa de los Muertos, occupied from 700 to 200 b.c., provide our earliest basis for understanding mortuary practices (Popenoe Reference Popenoe1934). Las Flores Bolsa, a riverbank site excavated in 1936, with a curated museum assemblage analyzed by Joyce, yielded Late Classic and Early Postclassic burials (Joyce Reference Joyce and Robinson1987; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). We integrate information, including determinations of sex and age made by the original excavators, contained in an unpublished burial catalog for Las Flores Bolsa and Playa de los Muertos (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936). Distinctions in treatment by age are consistent with other evidence for the importance of childhood in a life cycle marked by ritual from the Formative period to the Classic period (Joyce Reference Joyce, Grove and Joyce1999, Reference Joyce2003, Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011; Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006). They underline our conclusion that mortuary practices were a significant way that personhood was produced and social relations cemented in this region.

Burial Alignments and Cosmology

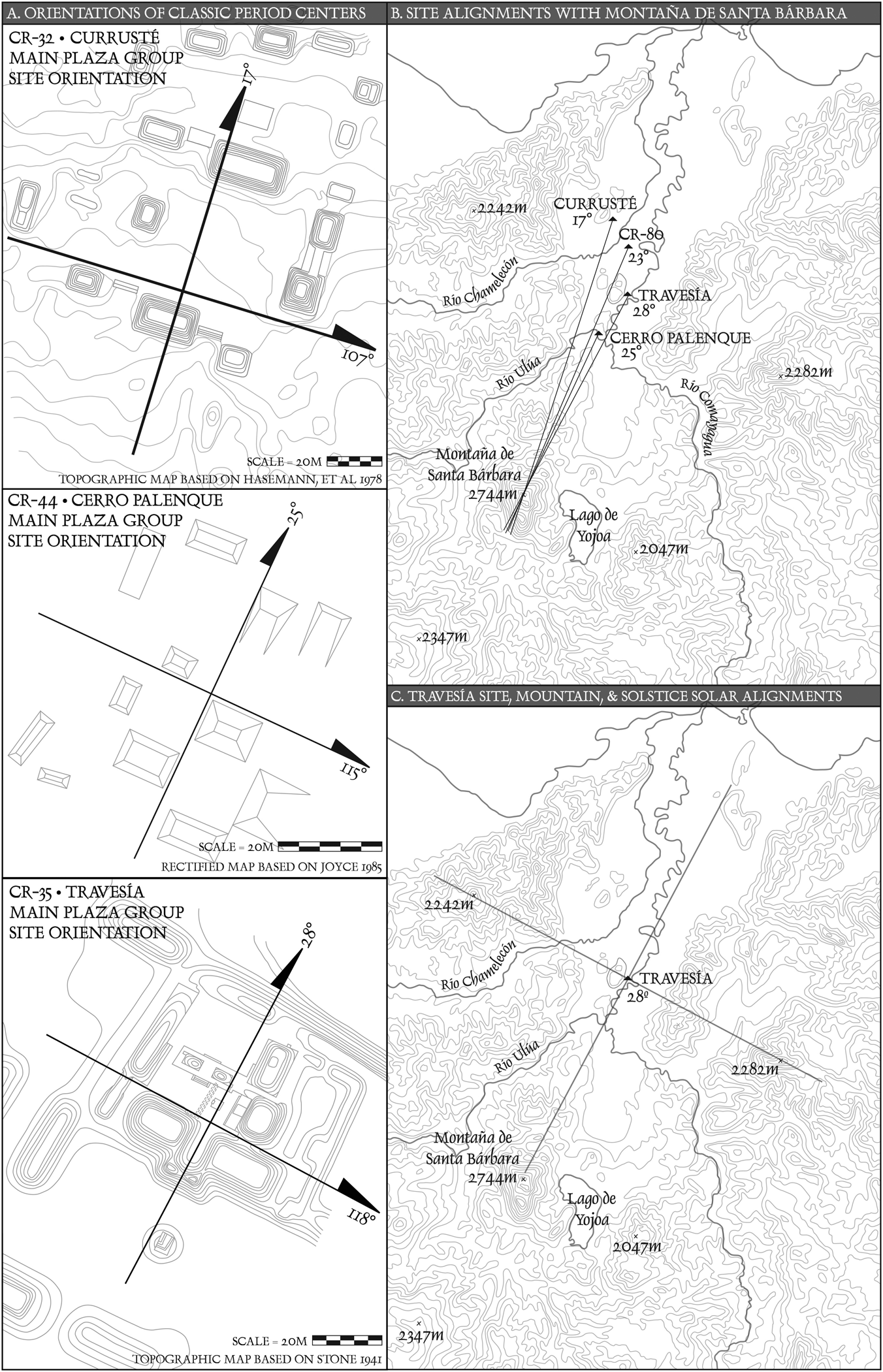

A significant aspect of our analysis of burials as historically connected practices is our use of previously developed models of cosmological and geographic orientations linking the politically independent towns in the valley (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2003, Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006, Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007). Lopiparo noted that orientations of burials at multiple Classic period sites were closely aligned with each other (Figure 2). Burials at CR-80, CR-103, and CR-381 shared a very narrow range of orientations, at 24° or perpendicularly within several degrees of 114° and 294°, though they often did not align with the structures or earthen platforms in which they were interred. Lopiparo (Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007) showed that the main plaza groups at Travesía, Currusté, and Cerro Palenque also shared a similar orientation with the burials and were generally aligned north-northeast/south-southwest (NNE/SSW) but with slight variations in precise orientations: 17° at Currusté, 25° at Cerro Palenque, and 28° at Travesía (Figure 3a). Two extremely eroded burials at Currusté were oriented with their heads pointed to the NNE. One was so badly preserved that it was not possible to discern a precise angle, but the angle of the other was approximately 15°. Both were closely aligned with the main plaza group at Currusté.

Figure 2. Late and Terminal Classic site and burial alignments at Cerro Palenque, Currusté, Puerto Escondido, Travesía, CR-80, CR-103, CR-132, and CR-381 (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Figure 3. Orientations of: (a) Classic period centers; (b) site alignments with the Montaña de Santa Bárbara; and (c) Travesía site, mountain, and solstice solar alignments (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Superimposing these orientations on a map of the valley revealed that the NNE/SSW burial axes and the axes of the main plaza groups at the three centers aligned with the Montaña de Santa Bárbara at the southern end of the valley (Figure 3b). At 2,744 m, this is the tallest mountain in the ranges that surround the valley. The perpendicular east-southeast/west-northwest (ESE/WNW) orientation aligned burials and main plazas with sunrise on the eastern horizon at the winter solstice and with sunset on the western horizon at the summer solstice. These alignments are not precise, but rather share with other ground-based observational astronomy the use of features on the horizon to align practices with seasonal transitions (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021:244–248).

The orientation of the main plaza at Travesía aligned the SSW axis of the site with the Montaña de Santa Bárbara and aligned the ESE/WNW axis of the site with the tallest mountain on the eastern side of the valley, over which the sun would have risen at the winter solstice, and the tallest mountain on the western side of the valley, behind which the sun would have set at the summer solstice (Figure 3c). It is probable that the Classic period residential compound of the most prominent family at Travesía was deliberately established at a location that would create this unique confluence.

In our present study, we find that burials at Formative period Playa de los Muertos already employed a NNE/SSW alignment orienting burials towards the Montaña de Santa Bárbara. Drawing on data from Late Formative to Early Classic burials at two additional sites, Puerto Escondido and Río Pelo, we suggest that landscape orientation of burials seen at Middle Formative Playa de los Muertos established a pattern used by later generations. We argue that these examples, from before 700 b.c. to a.d. 250, show long-term continuity of practices demarcating cosmological landscapes and their propagation as part of mortuary ceremonies shared by the politically independent towns of the valley.

As noted in previous work (Joyce Reference Joyce, Barber and Joyce2017b), initially the symbolic significance of the Ulúa cosmological landscape was terrestrial, including caves in the mountains. None of the burials at Playa de los Muertos employ the alignments to solar phenomena that are important in the Classic period. Consistent with a new emphasis on solar cycles, Late Classic burials all have their heads oriented to the ESE, WNW, or NNE, a change from the Formative period. This preference was evident by the Early Classic. In the neighboring region of Yoro, a ballcourt was constructed with an alignment to summer solstice sunrise between 200 b.c. and a.d. 150, the transition between Late Formative and Early Classic (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Lopiparo, Bowser and Zedeño2009:65–68; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Sheptak, Cyphers and Hirth2008:Table 1). By the seventh century, the main house compound at Travesía was located to combine solstice orientations with the traditional orientation to the southern mountain. The adoption of solstice orientations may reflect ritual practices linking Honduran people to peers in the Maya Lowlands, for whom solstice observations were important (Dowd Reference Dowd, Dowd and Milbrath2015).

During the transition to the Postclassic period, a new burial position, seated upright, was introduced in the Ulúa Valley. Multiple analyses show that for Maya people, the daily solar cycle, from sunrise in the east to sunset in the west, led to the identification of north with up, the position of the midday sun (Ashmore and Robin Reference Ashmore, Robin, Hendon, Overholtzer and Joyce2021). In the transition to the Postclassic period, a solar cosmological orientation that placed the body of the deceased in alignment with the position of the midday sun became dominant over the earlier alignment to significant mountains. The burials in this novel position occur with other evidence of participation in religious practices creating new social relations with a cosmopolitan network extending from Mexico around the Yucatan peninsula (Joyce Reference Joyce2019, Reference Joyce and Lyall2024).

Middle Formative Origins: Playa de los Muertos

Primary extended burials were placed under or near residential platforms in Honduran settlements in the Middle Formative period, with contemporary and even earlier use of caves for secondary deposit of skeletal elements (Joyce Reference Joyce, Grove and Joyce1999). After about 700 b.c., monumental platforms provided a new kind of context for burial for selected people (Joyce Reference Joyce, Grove and Joyce1999). In residential settings and monumental platforms, some people were buried wearing ornaments. Many burials in residential settings included pottery vessels or other objects. Vessels were also deposited near skeletal elements in caves.

In the Ulúa Valley, mortuary practices of this period are represented in greatest detail by burials recovered at Playa de los Muertos in the 1920s (Table 1). While a full report of the Playa de los Muertos excavations was never published, we combine details from a published article (Popenoe Reference Popenoe1934) with data from Joyce's recording of the collections curated at Harvard's Peabody Museum. Our analysis shows that groups of burials were placed in clusters, likely residential settings (Figure 4). A few burials in locations away from these clusters had more complex burial goods.

Table 1. Middle Formative burials at Playa de los Muertos

Figure 4. Plan showing locations and orientations of burials at Playa de los Muertos (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Initially, three burials (Table 1: Burial A, B, and C), one the remains of a child, the other two, adults, were recorded as a single cluster on the south end of an embankment actively eroding into the Ulúa River. The child and one adult were buried wearing jewelry, shell and jade in the case of the child, jade alone for the adult. The second adult, with no recorded body ornaments, was buried with two pottery vessels and two stone objects. A year later, the same area yielded four more burials from the same cluster (Figure 4; Table 1). The excavator assigned the seven burials in this cluster to two distinct strata, one 5.0–5.2 m deep (Burials C, 1, 2, 3), and one at depths from 2.0 to 4.0 m (Burials A, B, and 12). Six additional burials were excavated, forming central and northern clusters. These also included burials in two distinct strata. Burials 4, 5, 7, and 11 were not close to any cluster, each encountered apart from any other recognized features at depths from 4.4 to 4.7 m.

We propose that the clusters of burials were placed by three burying populations living in nearby houses, the remains of which were not recognized during early twentieth-century excavations. Almost 50 years later, renewed excavations in what remained of the site detected features composing house foundations, trash pits, and working surfaces beginning ca. 2 m below current ground surface extending to 4 m deep (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1981:49). Distinct strata with refuse deposits, a cache of three vessels, and an intact hearth formed the context for two additional burials (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1981:52–57). The excavator defined “two distinct cultural horizons,” one at 2.0–2.7 m deep associated with a 3.1 m long house pit, and an earlier one at 2.8–3.4 m associated with the remains of a second house (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1981:57–58). Two burials were recovered in association with these features (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1981:49–50). The first was an extended burial “oriented from east to west” at a depth of 2.85–3.05 m below the surface. The person in this burial was wearing a jade bead wristlet. At a depth of 4.0–4.2 m, a second burial was encountered, flexed but also described as oriented east to west, without any accompanying objects (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1981:50).

We recognize an early occupation (Kennedy's Sula ceramic complex, now dated as 700–400 b.c.; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Sheptak, Cyphers and Hirth2008) represented by residential structures buried between 2.8 and 3.4 m deep, associated with burial practices that resulted in Popenoe's “earlier stratum” of burials. A later occupation (Toyos complex, ca. 400–200 b.c.) with a better-preserved house structure at 2.0–2.7 m deep corresponds to what Popenoe recognized as her later stratum of burials. The burials at this site thus come from a multigenerational residential population placing the bodies of at least some of the dead to rest, including adults and children, below floors of houses and house yards.

Popenoe (Reference Popenoe1934) recorded detailed information about burial position and orientation for 14 burials. Nine have a NNE/SSW orientation, three with their heads oriented to the NNE and six with their heads oriented to the SSW. These burials were closely aligned with the Montaña de Santa Bárbara (Table 1, Figure 5), suggesting that this key point on the landscape was important to the people of Playa de los Muertos. This pattern conforms to the tendency for Classic period burials to be oriented to common features on the landscape, and to the Montaña de Santa Bárbara in particular, observed in earlier work (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007).

Figure 5. Formative period site and burial alignments at Playa de los Muertos (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Two adults (Burials 1 and 2) in the southern cluster shared a single burial pit, their bodies at opposite angles. Nine bodies were in extended position, the majority prone, and seven were flexed. Prone and flexed positions were employed both early and late. Burial 6, placed in the late period, was in a seated posture. Clusters reflected distinct preferences in burial position, with all burials in the northern cluster flexed and all but one burial in the southern cluster in an extended prone position. The central cluster contained burials in both positions, as well as the unique burial in seated position.

About half the burials included no artifacts. Two contained only ceramic vessels and stone objects. Seven burials that included body ornaments also contained other artifacts. Six of the dead were buried wearing jade or jade and shell ornaments, with shell ornaments distinctive of three burials identified as children. Two of these (Burials A and 14) lacked any additional burial accompaniments. Burial 8, however, was among the most elaborate at the site, with three ceramic vessels and two figurines, the only examples of figurines in the 19 documented burials.

Four burials (Burials 4, 5, 7 and 11) were isolated from the three clusters (Figure 4). They stand out not only for their location but for their large and distinctive burial assemblages, containing items not seen otherwise, including pigments and tools for preparing and applying them. They included a large number of pots, some with complex iconographic motifs. These were all adults, two (Burials 5 and 11) wearing ear ornaments, and the other two wearing unique stone pendants. In figurines of this period, ear ornaments and unique pendants are interpreted as characteristics of representations of elders, older adults in seated postures (Joyce Reference Joyce2003). We suggest these four adults had unique status in the community that led to them being singled out for special burial treatment beyond their own household.

Mortuary ritual at Playa de los Muertos was thus complex. The treatment people underwent at the transition from life to death was part of a series of life-cycle rituals emphasizing aspects of embodiment also evident in figurines (Joyce Reference Joyce2003). Body ornaments included in burials related the person to the age-based categories of child, young adult, and older adult, which were singled out in visual culture. Yet specific ornaments of each burial were individualized. The children in Burials A and 14 each wore wristlets that included shell beads but in different arrangements (Burial A had only shell beads and Burial 14 had rows of greenstone beads on either side of a row of white shell beads). The child in Burial 8 wore a necklace of shell beads with a shell skull and two greenstone duckbill pendants, while the adult in Burial C wore a greenstone bead necklace with three duckbill pendants.

Social relations were indexed in the more isolated burials by the inclusion of vessels appropriate for food sharing. Based on vessel forms, we suggest mortuary ceremonies involved shared meals. Small cylindrical cups of an appropriate size for drinking were included in at least three burials (Burials 3, 8, and 11). The most distinctive vessels found are spouted bottles (Burials C, 8, and 11). In contemporary deposits at Puerto Escondido, residue analysis confirmed similar bottles contained cacao (Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Joyce, Hall, Jeffrey Hurst and McGovern2007; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2007). We thus suggest mortuary meals at Playa de los Muertos included cacao drinks.

Burial contents not only connected the dead to the living; they commemorated connections to ancestral times. Miniature pots in isolated Burials 4, 5, 7, and 11 reproduce forms and decorative motifs already archaic by 700 b.c. Too small to be of pragmatic use for food storage or serving, several were identified by the excavator as containing pigment. One miniature jar has incised designs that include alternating profile zoomorphic faces, one with a prominent shark's tooth. These motifs are similar to, perhaps based on, Olmec-related designs employed by potters at Puerto Escondido between 1100 and 900 b.c. (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2010, Reference Joyce, Henderson, Blomster and Cheetham2017), which reflected the emergence of a cosmological understanding of the lower Ulúa Valley as a place at the edge of primordial oceans (Joyce Reference Joyce, Barber and Joyce2017b:153–160).

We suggest that primary burials at Playa de los Muertos were one stage in multipart mortuary cycles that also involved deposits of selected skeletal remains in caves. In Honduras, secondary burial in caves was recognized in Olancho in eastern Honduras, in the Aguán Valley northeast of the Ulúa Valley, and in the Copan Valley to the west (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Begley, Fogarty, Stierman, Luke and Scott2000; Gordon Reference Gordon1898a; Healy Reference Healy1974; Herrmann Reference Herrmann2002; Joyce Reference Joyce, Grove and Joyce1999, Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). Caves in Olancho were used before 900 b.c. and continuing into the Middle Formative, contemporary with Playa de los Muertos (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Begley, Fogarty, Stierman, Luke and Scott2000; Herrmann Reference Herrmann2002). Caves in the Aguán Valley, the known cave burial site closest to the lower Ulúa Valley, contain figurines and vessels identifiable with styles defined at Puerto Escondido for the period 1100–900 b.c. (Joyce Reference Joyce2003; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2007). At Copan, vessels from caves resemble others in primary burials in household compounds dating before 900 b.c. (Viel and Cheek Reference Viel and Cheek1983). Continued use of the Copan and Aguán caves contemporary with Middle Formative Playa de los Muertos is less certain than at Olancho, but Classic period use of caves at Copan has been confirmed.

These regional patterns suggest that during the Formative period, in villages across Honduras, residential group burial was the primary mortuary treatment, in some cases followed by secondary mortuary rituals resulting in placement of bones in mountain caves. During this cycle, individualization of the dead in primary burials through wearing unique body ornaments was followed by the creation of a communal group of less individuated ancestral persons. An interplay of individualization, commemoration of relations to the burying community, and embedding in a cosmological understanding of the relationship of the living to the ancestors anchored in landscape features, specifically mountain caves, was established by the end of the Formative period. This provided a framework for the development of mortuary ritual in the Classic period by the descendants of the people of Playa de los Muertos and other early villages.

Classic Period Mortuary Contexts

After a gap of more than 600 years, our record of burial practices resumes with data from multiple Classic period sites. For the first part of the Classic period (ca. a.d. 400–630), we draw on information from Puerto Escondido (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011) and excavations at Las Flores Bolsa and Playa de los Muertos (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). Our data for the period after a.d. 630 come from excavations at sites including Currusté (CR-32), CR-68, CR-69, CR-80, CR-103, CR-132, CR-157, and CR-381 (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979; Hendon et al. Reference Hendon, Joyce and Lopiparo2014; Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo1994, Reference Lopiparo2003; Swain Reference Swain1995). Most of these sites are residential. Currusté, CR-157, and CR-132 each have some nonresidential architecture, but the primary burials come from residential settings, making these samples comparable in social context.

Early Classic Mortuary Data

Our largest Early Classic period sample (Table 2) comprises 21 burials in house clusters arranged around external yards containing burned features and associated with bell-shaped storage pits at Puerto Escondido (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). Extended burials were most common (16 examples). At least three skeletal deposits consisted of isolated elements, long bones in two cases and a cranium (without mandible) and ulna in a third. Red pigment applied to these bones supports their interpretation as products of secondary mortuary treatment within the village. Three juveniles were identified, and at least one burial was of an adult woman.

Table 2. Early Classic period burials

Early Classic burials at Puerto Escondido were placed under house floors or in adjacent house yards. The position of the body is generally extended, as it was most often at Playa de los Muertos. Yet in other ways, the burial practices of the Classic period appear quite different. Most of those buried wear no body ornaments, the principal exception being earspools of fired clay identical to those in Formative period burials. Complete vessels and other artifacts are absent.

Our analysis includes one burial from Río Pelo (Wonderley Reference Wonderley and Fowler1991) and 10 from Las Flores Bolsa, which included adult and juvenile males and females, as identified by the original excavators (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936). We identified two additional burials from excavations at Playa de los Muertos dating between a.d. 250 and a.d. 450 based on associated ceramics. These burials were adults, one identified as female, and both in extended positions described as supine and on the left side. As discussed further below, these burials may show transformation in the practice of including pottery vessels in burials toward forms of commemorative structured deposition that became common in the Late Classic period.

Late to Terminal Classic Mortuary Data

We examined data from 10 sites to explore Late to Terminal Classic burial practices and secondary mortuary features (Table 3 and Table 4). Our original model of Late to Terminal Classic mortuary practices is based on fine-grained excavations by Lopiparo (Reference Lopiparo2003, Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006, Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007, Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo2009) at Currusté, CR-80, CR-103, and CR-381. Based on our participation in earlier excavations at CR-103 and CR-132, we added five mortuary contexts from CR-103 (Murray Reference Murray1985; Joyce personal communication, Reference Joyce and Lyall2024) and six from CR-132 (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo1994; Swain Reference Swain1995). Information recorded in a field report of 35 burials excavated in residential groups at CR-68 and CR-69, although less complete, was also reviewed in our analysis (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979), as were Late Classic burials from Las Flores Bolsa, recorded in a field catalog that provided partially comparable information (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936).

Table 3. Late and Terminal Classic period burials

Table 4. Classic period bone bundles and secondary burial data

Most of the burials at the sites where Lopiparo (Reference Lopiparo2003) excavated were extended on their sides and were adjacent to house structures or at the bases of house platforms rather than directly under house floors, a pattern that Hasemann (Reference Hasemann1979) also noted for CR-69. One notable exception was a double burial at CR-80, with two adults interred side by side beneath the floor of a structure on the tallest platform surrounding the patio. Hasemann (Reference Hasemann1979) noted that almost all of the adult and subadult burials at CR-69 were extended (27 out of 28). Where burial position could be determined, three were supine or prone and 20 were interred on their side. Excavations at CR-132 uncovered six sets of human remains (Swain Reference Swain1995), including two infant burials, two adult burials, and two secondary burials. These came from what was likely a household group that predated construction of a ballcourt that later covered the area (Hendon et al. Reference Hendon, Joyce and Lopiparo2014:69).

Afterlife cycles and Social Integration: Interpreting Classic Period Mortuary Practices

Based on our analysis of Classic period burial data, we identify four aspects of mortuary ceremony contributing to the reproduction of social relations in the heterarchical network of communities in the Ulúa Valley. First is a shared approach to disposal of the dead rooted in an ancient orientation to sacred mountains, which develops with the addition of solar orientations during this period. Second is variation with aspects of personhood, most notably age. Third is the integration of burials into more extensive patterns of ritual action that we recognize through analysis of structured deposition. Finally, we suggest that social relations formed around care for the remains of deceased group members and that commemoration of the dead perpetuated the integration of communities. We explore these patterns by connecting mortuary data to evidence from cosmology and visual culture.

Burial Alignments, Geography, and Cosmology

The shared orientation of burials toward the Montaña de Santa Bárbara, already seen at Playa de los Muertos, established a pattern continued by Classic populations. Eleven out of 14 Early Classic burials at Puerto Escondido are oriented NNE/SSW or ESE/WNW, and among them, a cluster of six adhere remarkably closely to the angle between Playa de los Muertos and the Montaña de Santa Bárbara or are perpendicular to it (Table 2, Figure 6). An additional five burials are within 15° of that orientation. The only recorded Early Classic burial from a platform at Río Pelo employs this orientation as well. Based on Anthony Wonderley's (Reference Wonderley and Fowler1991) site map and description, this burial was oriented perpendicular to the those at Puerto Escondido and Playa de los Muertos, at approximately 118°. The burials at Puerto Escondido and Río Pelo were not directly aligned with the Montaña de Santa Bárbara. Instead, they employed the predominant orientation used at Playa de los Muertos, where this angle had aligned with the mountain. Examples that span the Middle Formative, Late Formative, and Early Classic indicate the long-term continuity of practices demarcating and perpetuating cosmologically significant landscapes as part of shared mortuary treatment.

Figure 6. Early Classic site and burial orientations at Puerto Escondido and Río Pelo (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

In Late Classic period burials, we see each community orienting itself to the Montaña de Santa Bárbara. At Currusté, CR-80, CR-103, and CR-381 burials were extended on their sides with their legs slightly flexed, oriented either NNE/SSW or perpendicular to this axis with an ESE/WNW orientation (Table 3, Figure 2, Figure 7). Six NNE/SSW burials were oriented with their heads pointing NNE. The four that were preserved well enough to determine burial position were on their left sides (facing east). Of the four ESE/WNW burials, two were oriented with their heads pointing ESE on their right side (facing north) and one was interred with its head pointing ESE on its left side (also facing north). The fourth was an infant, which was semi-flexed with its head pointing WNW but on its right side facing south.

Figure 7. Classic period burial orientations (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Less precise burial data from other sites are consistent with this pattern. At CR-69, crania were oriented either to the north or the east in every case in which the excavator was able to determine the burial orientation (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979). Descriptions of four burials at CR-103 appear consistent with this pattern (Murray Reference Murray1985), and a field drawing of a fifth burial at CR-103 by Joyce shows it was oriented ESE/WNW at about 114°. Three burials recorded at CR-132 also conform to this shared orientation (Swain Reference Swain1995).

Solar alignments, not detected in Middle Formative burials at Playa de los Muertos, are newly identifiable in Classic period burials. The new emphasis on solstitial alignments, seen in the placement of the main house compound at Travesía, may reflect adoption of cosmological ideas developed in the Maya Lowlands. Travesía's leading family had many connections with contemporary Lowland Maya noble families (Joyce Reference Joyce2017a:222–225, 260–261; Luke and Tykot Reference Luke and Tykot2007). Visual elements identical to images of dances that marked events in June at Yaxchilan appear on Ulúa Polychrome pottery created in the late eighth and early ninth century, another indication of integration of Maya cosmological concepts at this time (Joyce Reference Joyce2017a:174–175, 294–295).

Consistent with a new emphasis on solar cycles and the path of the sun, Late Classic burials all have their heads oriented to the ESE, WNW, or NNE, a change from the Formative period burials at Playa de los Muertos, where more than half had their heads oriented towards the SSW. This shift was already evident in the Early Classic, when the majority of burials had their heads oriented to the ESE, WNW, or NNE, and only one was oriented to the SSW. Of the 29 Early, Late, and Terminal Classic burials for which we determined the burial positions of the head, 24 are facing north or east, four are facing south, and one is facing west (see Table 2 and Table 3). Three of the four burials facing south are infants, and of the four infant burials, three are facing south. Differences in burial position were likely related to concepts of personhood as unfolding over life stages, an observation supported by other aspects of treatment of children.

Burial Position and Personhood

Beginning in the Formative period and continuing into the Terminal Classic, bodies of the dead were most commonly extended. Infant burials often present variations in burial patterns from adults in the same sites. They are more likely to be flexed, and it is not always possible to determine their orientation. In one case from our excavations where we have a precise orientation for an infant burial (CR-103 10X-3), it faced in the opposite direction to the adult and subadult burials that share its angle of orientation (facing south instead of north). Joyce's examination of field drawings shows the same is true for a subadult burial documented at the site of Las Flores Bolsa (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936).

The suggestion of a shared understanding of infants as distinct from adults is reinforced by other data. Infant burials at CR-132 shared the same WNW/ESE orientation as the infant at CR-103, one in the same position with their head to the WNW on their right side facing south, and the other with their head to the ESE on their right side facing north (Swain Reference Swain1995). A second burial from CR-103 documented by Joyce was an infant flexed and placed into a small pit, oriented with the head towards the east-northeast (ENE). An infant burial at CR-69 was placed across the neck and torso of an adult (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979).

These differences in mortuary rituals distinguish life stages of children and adults. Late Classic Ulúa visual culture reinforces childhood as a distinct life stage. Figurines juxtapose children and adults, specifically, mothers holding smaller figures on or in front of their knee or grasping one of their breasts (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006). These children are sometimes dressed with ornaments and headdresses that echo those of the adults with whom they appear. Unlike in the earlier Playa de los Muertos culture, children do not seem to be independent subjects of Late Classic figurines, suggesting they were seen as dependent on adults to a degree that was more pronounced than in the Formative period. A shift in emphasis from Formative period individuation to Classic period community is also evident in broader ritual practices.

Connecting the Community: Structured Deposition and Commemoration

Ulúa Classic period burials were interred in earthen pits that were not prepared or distinguished from their surrounding fill. While associated grave goods are unusual, many burials are associated with structured deposition resulting from repeated ritual practices accompanying the interment of houses and their inhabitants, practices through which the living interacted with the dead (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2003, Reference Lopiparo, Ardren and Hutson2006, Reference Lopiparo and Beck2007, Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo2009, Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021). The concept of structured deposition, which was defined to identify materials that otherwise might be considered neutral forms of waste as residues of meaningful action (Richards and Thomas Reference Richards, Thomas, Bradley and Gardiner1984), is useful in interpreting these practices as part of the ritualization of everyday actions (Bradley Reference Bradley2003). It allows us to connect burials with wider sequences of actions that were significant in reproducing communities.

While in most Classic period burials we excavated, no objects were deliberately included, earspools are a significant exception. Wearing earspools marked the achievement of adult status in Formative period visual culture (Joyce Reference Joyce2003). At Puerto Escondido, detailed analysis showed that most earspools in burial contexts were not pairs worn by the deceased, but fragments, sometimes of multiple different earspools (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). At this site, earspool fragments were statistically more likely to occur in units near burial locations. The structured deposition of earspools, and likely their predepositional breakage, were apparently steps in mortuary ritual.

Complex mortuary rituals connecting the dead to others may also be responsible for the few examples of Classic burials where more associated artifacts have been reported. At Early Classic Playa de los Muertos, one adult was buried with a complete fragmented vessel over the lower legs, and a second adult was buried with pieces of a single vessel next to and over the cranium (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936). Rather than grave goods related to individual social identities, these vessels are residues of actions during placement of burials. In a second burial from Early Classic Playa de los Muertos, a fired clay body ornament, possibly a labret, was encountered near the cranium, and a single obsidian blade was near the left hand. In one burial from Santa Rita, a plain bowl was inverted over the skeletal remains of a child (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936). An obsidian blade was noted in the earth around an adult skeleton at Santa Rita, and another near an adult female in a Classic burial at Las Flores Bolsa. Such individual objects are ambiguous; they could simply have been casually discarded in fill. We gain confidence in our interpretation of these objects as evidence of structured deposition from other more complex contexts.

In a seventh-century burial from Puerto Escondido, an individual was placed in extended position on layers of carbon, ash, and clay in a subfloor pit with a restricted circular aperture (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). Fragments from at least five distinct earspools (including two complete earspools from different pairs, and seven other fragments) were in the pit fill. Also present were a variety of costume elements: a feline incisor, a shell “tinkler,” and a tubular gray ceramic bead. Like the fragments of earspools, although these were body ornaments, they were deposited in isolated ways, not worn. The only object clearly associated directly with the body was a rectangular, black obsidian plaque, abraded on all edges, made from a very large blade (30 by 32 mm). An example of an obsidian mirror, this costume element may once have been part of a larger assemblage like the other singular ornaments in this burial pit.

No complete artifacts were placed in this burial. The body was covered by lenses of carbon-rich soil alternating with clay, which included mixed pottery fragments, some from very unusual vessels, and obsidian flakes and blades, filling the pit. The pit neck was blocked by large ceramic sherds and fragments of up to 20 figurines. The final closing of the pit was accomplished by the deposit of pieces of three-dimensional effigies from two censer lids representing a feline and a standing human figure. Fragments of five small cylindrical candaleros, vessels used for burning resin, were included as well. The figurines and censers were used and discarded as part of a final stage of mortuary ritual after an earlier phase that included the burning of plant materials and the use and breakage of finely crafted vessels appropriate for serving beverages.

The inclusion of broken figurines inspired us to examine whether figurines were normal parts of cycles of mortuary ritual at Puerto Escondido. Fragments of figurines were present in surrounding fill near 14 of 18 burials included in the analysis (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). In contrast, only half of the 36 excavation units without burials had fragments of figurines. Figurines were apparently used in rituals carried out by the living near where the dead were buried rather than being deposited as individual possessions or personal identity markers of the deceased.

The locations of burials were sites for sequences of ritual practice through which the living interacted with the dead over time, processes that are archaeologically detectable in the form of structured deposition. Fine-grained excavations of an unusual double burial at CR-80, featuring two adults interred side by side beneath a house floor, provided another elaborate example (Figure 8a). Although these burials were only 50 cm apart and shared the same position and orientation, extended on their left sides with their heads pointing 24° NNE, stratigraphic evidence and differential preservation indicate they were not interred at the same time. The western burial was extremely eroded, leaving only casts of bones that were almost entirely disintegrated. While we were able to determine the position and orientation of the burial from these casts, no small bones were preserved, and the long bones and skull were extremely fragmented. The eastern burial was much better preserved. Though the skeleton was also fragmented and eroded, the small bones of the foot and ribs were still present and the skull and leg bones were much more intact. This differential preservation indicates distinct microenvironmental conditions, suggesting the two were not interred in the same burial pit.

Figure 8. Subfloor double burial (a) and structured deposits (b) from CR-80 (illustration and photo by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Stratigraphic evidence indicates that multiple episodes of ritual activities preceded the first burial and followed the second (Figure 8b). First, a complete jar rim and neck, broken off a tall, flaring-neck jar, was buried upside down. Organic material was then burned inside of the cavity created by this buried, overturned jar neck, which was filled with ash. Ashen traces of a woven mat were found on the surface adjacent to the buried jar neck, and two whole obsidian prismatic blades were aligned next to it. The western burial was interred on top of this deposit, its legs partially covering the jar, indicating that the body was buried after the set of rituals associated with the buried jar neck. The legs of the western burial rested right on top of these deposits. In contrast, the base of the eastern burial was several centimeters above the level of the earlier deposits, providing additional evidence that the two burials were not interred at the same time in the same pit. After the second burial was placed, fragments of a figural incensario and a whole figural ocarina were interred above the burials near their feet. The base of this deposit is at the approximate level of the top of the burials, suggesting it comprised structured deposition from a later set of ritual activities in the same location.

Other examples of Classic period structured deposition associated with burials were not as elaborate as these two contexts. Several examples consisted of partial smashed vessels adjacent to or on top of burials. At Currusté, two layers of smashed ceramics were recovered from above a highly eroded burial in the earthen fill of a cobble mound (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2009). This included large sherds that comprised about half of two different undecorated, coarse paste jars with evidence of burning. At CR-132, one burial was described as having a large, smashed vessel placed at its feet (Swain Reference Swain1995). Excavation photos reveal that the sherds, encountered in a circular pattern, were not from a complete vessel but rather a large fragment of a jar with evidence of burning. Pieces of obsidian and shell were recovered from below this ceramic deposit. Another burial in this area was associated with a series of deposits that included a dense lens of ceramics, shells, lithics, with carbon above the burial and a spondylus shell found nearby (Swain Reference Swain1995).

These carefully excavated examples showing sequences of deposition involved in household mortuary practices allow us to interpret similar evidence described by earlier excavators as structured deposition. The presence of single obsidian blades near burials at Las Flores Bolsa and Santa Rita may be evidence of ritual action related to but distinct from interment (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). Two burials from Las Flores Bolsa rested near or over patches of burned clay, which could have been created in events involving burning of materials like that noted at CR-80. In two cases at Las Flores Bolsa, excavators noted complete small vessels within a meter of a burial, not in apparent direct association, but possibly resulting from a sequence of ritual practices.

Across these contexts, a pattern of structured deposition incorporating roughly half of a broken vessel or figural artifact, sometimes associated with burning events, was common. If we did not recognize them as results of intentional breakage and structured deposition, deposits of partial artifacts like these could be misidentified or mischaracterized as fill (Lopiparo and Joyce Reference Lopiparo, Joyce and Miniaci2023). Such structured deposits show that burials were part of sequences of ritual actions through which household members commemorated the dead.

Layered memory was created through interment, whether what was buried was a human body or a meaningfully arrayed group of artifacts (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). It was also created through disinterment and the afterlife cycles of humans as they transformed into ancestors via the transformation of bodies themselves (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021), including the retrieval of human skeletal elements from primary burials and their incorporation in secondary deposits.

Reentries, Bone Bundles, and Group Identity

Classic period mortuary practices included a cycle of secondary ritual that involved the manipulation of skeletal elements, notably long bones and skulls. The selection of bones to be reinterred in bundles in select locations, similar to practices in the contemporary Maya Lowlands (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Fitzsimmons and Shimada2011; Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Aspöck, Klevnäs and Müller-Scheeßel2020), has deep history in Middle Formative Honduras, though the Classic period cycle of mortuary ceremonies involved a significant change. Skeletal elements displayed in commemorative rites within Classic period settlements in the lower Ulúa Valley maintained integrity as bone bundles rather than being removed to distant, commingled sites of deposition in caves.

Structured deposition with evidence of multiple reentries, in many cases associated with human burials, has been described for sites throughout the valley, including deposits in which ceramic vessels, jar necks, figurines and figural whistles, and figural incense burners were used, smashed, and buried (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021; Lopiparo and Joyce Reference Lopiparo, Joyce and Miniaci2023). Additional evidence that implies reentry includes secondary burial practices and recovery of human bone bundles and disarticulated crania (Table 4) from at least seven sites (Hasemann Reference Hasemann1979; Hendon Reference Hendon2010; Hendon et al. Reference Hendon, Joyce and Lopiparo2014; Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011; Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021; Murray Reference Murray1985; Swain Reference Swain1995).

At Currusté, Lopiparo (Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021) documented the most elaborate example of secondary mortuary practices we have recorded. These deposits provide a particularly detailed window into the afterlife cycles of the ancestors, or the processes of exhumation, preparation, and bundling of skeletal elements and acts of care, feeding, and veneration that were key components of reciprocal relationships among the living and between the living and the dead (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021). The deposit included six large figural censers that were smashed in place after use and were interred on top of multiple long bone bundles and two crania in a nonresidential setting at the western edge of the North Plaza (Figure 9). The deposit included a censer fragment showing a hand grasping a bundle of long bones tied at the ends (Figure 10a).

Figure 9. Currusté ceramic midden, broken figural incense burners, and human bone bundles (illustration by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Figure 10. Skeletal imagery: (a) incensario fragment of anthropomorphic hand grasping a long bone bundle from Currusté; (b) carved femur from CR-80; (c) stamps with skeletal imagery from CR-103, CR-80, and CR-381; (d) miniature mask mold and mask from CR-381; and (e) whistles from CR-381 (photos by Jeanne Lopiparo).

At Puerto Escondido, an articulated burial with pigment adhering directly to the bones is evidence of burial reentry, along with three deposits of crania and long bones covered with pigment and a deposit of multiple long bones (Joyce Reference Joyce, Adams and King2011). At Cerro Palenque, Julia Hendon recovered incensario fragments representing a long bone tied with rope, along with a single human femur, in structured deposition associated with the construction of a terrace (Hendon Reference Hendon2010). At CR-69, Hasemann (Reference Hasemann1979) noted a disarticulated cranium that was seated on the pelvis of an articulated burial, and at CR-103, Murray (Reference Murray1985) reported two skulls that were not associated with any other bones. Lopiparo also recovered a partial carved long bone from CR-80, which appears to be the distal end of a femur (Figure 10b), though we cannot be certain it is human because of modification and breakage.

Other examples may be more ambiguous, due to poor preservation and the complex occupation histories of sites. Multiple skull fragments, a disarticulated infant burial, and a deposit of arm bones and a scapula were documented in excavations at CR-132 (Swain Reference Swain1995). Poorly preserved deposits of disarticulated long bones were recovered from Terminal Classic residential contexts at Currusté, CR-80, and CR-103 (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2003, Reference Lopiparo2008). We have recovered burials with missing limbs, for example, a burial at CR-103, missing its lower legs, associated with a burned and buried house. We have also found evidence of disturbed burials, where only fragments of bone and teeth are recovered.

Excavations have revealed significant depositional evidence for interaction between the living and the dead at sites throughout the valley, including rituals of commemoration in place through time and burial reentry for the removal, treatment, bundling, circulation, and reburial of human skeletal remains. Related practices and iconography are also represented in Ulúa visual culture. In addition to the examples described above of incensario fragments representing long bones tied with rope, stylized representations of skulls appear in ceramic media, including stamps representing skulls or skeletal figures with skulls at their waist (Figure 10c), miniature masks representing skeletal faces (Figure 10d), and small skull whistles (Figure 10e).

Ulúa Polychrome vessels from the seventh and eighth centuries depict bundles as foci in rituals (Joyce Reference Joyce2017a). In the simplest versions, a vertically oriented object supports an animal figure. Joyce (Reference Joyce2017a) has argued that these animals are anthropomorphized characters from founding narratives. One vessel of this kind shows a complex bundle with a human figure facing the animal (Joyce Reference Joyce2017a: Figure 26). The lower part of the bundle is an oval standing on low feet, and the bundle is tied with rope (Figure 11a). An orange, red, and white collar above the rope-tied bundle has rectangular tabs used by Ulúa artisans to represent bark paper. On top of this paper-topped, rope-tied bundle stands a bird with a long tail. An identical bundle is carried by a person using a tumpline in a procession on another eighth-century Ulúa Polychrome (Figure 11b). The details of the tied bundle link it to houses on other Ulúa Polychrome vessels. In one example (Figure 11c), a feline reclines on the roof of a profile building, paralleling the animal figures atop tied bundles (Kerr Reference Kerr1994:558). The roof has a fringe of tabs like those suggesting bark paper on the bound bundles. This image, and others like it, portrays an anthropomorphic figure seated inside the building, taking the place occupied by the bound bundle.

Figure 11. Ulúa Polychrome vessels showing the link between tied bundles and ancestral houses. Comparison of vessels in: (a) the Museo de San Pedro Sula, Honduras (original photo by Russell Sheptak, used with permission); (b) the Hudson Museum at the University of Maine Hudson Museum (HM 516, Kerr database K6992); and (c) a vessel published as K4577 (Kerr Reference Kerr1994:558). Original photos (b) and (c) by Justin Kerr. Justin Kerr photograph collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The equation of the bound bundle with a house is supported by a unique three-dimensional ceramic sculpture of a pregnant woman that originally stood on the lid covering one of the incensarios from Currusté (Figure 12). The woman carried a bundle on her back, in the form of a small three-dimensional house, supported by a tumpline (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo2008, Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021). This sculpture was deposited as part of the elaborate incense burning and secondary mortuary rituals at Currusté that included the interment of multiple bundles of skeletal elements. The depiction of a hand grasping a bundle of bones from another figural censer from this deposit (Figure 10a) reinforces the association of incense burning with the care, feeding, and veneration of the ancestors. Maya ancestral shrines often took the form of miniature houses (Lorenzen Reference Lorenzen2005) like the one carried by the woman from Currusté, which is stylistically very similar to the carved, replica house shrines documented at Mayapan (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Ledyard Smith1962:335, Figure 6). We argue that both the bound bundles and the miniature house carried by the Currusté woman represented ancestral connections of the social group created through mortuary rituals. The fact that she is pregnant further emphasizes the intergenerational connections between the living and the dead.

Figure 12. Ceramic figural incense burner from Currusté showing a pregnant woman carrying an ancestral house with a tumpline (photos by Jeanne Lopiparo).

Compared to earlier Formative period burial practices, the Late to Terminal Classic Ulúa Valley de-emphasized individuation, creating connections among the population and placing people in relation to a shared cosmological landscape. The collective ancestral dead were kept close at hand, and both imagery and excavated deposits suggest the remains of some ancestral beings may have been bundled, handled, and engaged with in ritual. This emphasis on the collectivity changes with the transition from the Classic to the Postclassic period.

Death in the Postclassic Ulúa Valley

Very few archaeological sites in the lower Ulúa Valley have recognized components dating after the Terminal Classic period. Only two sites yielded burials that can be attributed Postclassic dates. At Las Flores Bolsa, an Early Postclassic component with two or possibly three burials follows an earlier occupation with 11 burials that match the patterns Lopiparo defined for the Late to Terminal Classic (Joyce Reference Joyce and Robinson1987; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). At El Remolino (CR-260), a multicomponent site, the latest levels yielded one burial clearly dating to the Late Postclassic (Wonderley Reference Wonderley and Henderson1984).

We thus add to our analysis of late mortuary practices in the Ulúa region a series of burials and associated structured deposits from a central platform in a residential compound at Los Naranjos, a site located in the mountains south of the valley (Baudez and Becquelin Reference Baudez and Becquelin1973; Joyce Reference Joyce2017a:201–203). Here, a series of three structured deposits accompanies 10 interments, one assigned by the excavator to the Late Classic Yojoa phase, the rest to the Postclassic Rio Blanco phase (Table 5).

Table 5. Postclassic burials

The sole Yojoa phase burial, Burial 10, has an orientation skewed from the cardinal direction, also not simply aligned with the platform in which it was placed, like Ulúa Classic period burials. This orientation, approximately 30°, suggests a shared practice of using an alignment towards a local, but distinct, cosmography. Yet in two other ways, this burial is different from the more than 85 Classic burials documented for the Ulúa River Valley. The body, an adult, was placed with arms and legs flexed, rather than extended. Included near the body were two pairs of obsidian bifaces, and a pair of vessels: a jar covered by a fragmented bowl.

Eight of the nine burials that were subsequently deposited in this platform were also accompanied by objects. Four contained juveniles, ranging in age from a very young infant to an estimated six to eight years. Two juveniles were buried with greenstone ornaments, and a third had a copper pendant. The fourth was buried with no preserved objects. The infant with the pierced copper pendant also had a reworked sherd disk and a small incised bowl. The three juveniles buried with objects were highly fragmented, and no burial position could be discerned. The fourth juvenile, an infant, was laid on their left side, head north, with their legs flexed, a position mirroring that of the adult in the earlier Burial 10, reversing the position of the head, as in Classic Ulúa burials. The flexed position of the Late Classic Yojoa phase adult and the Rio Blanco phase child recalls the flexed position of the only burial reported from Early Postclassic El Coyote, north and west of Los Naranjos, where a juvenile, aged seven to nine, was interred without objects, head directed north (McFarlane Reference McFarlane2005:537).

Five other Postclassic burials here contained remains of six adults. Every one of these burials was accompanied by either worked bifaces, worked bone, greenstone ornaments, pottery vessels, or a combination of these. Each burial assemblage was different. All of the vessels are Early Postclassic types, including the Las Vegas Polychrome type that replaced Ulúa Polychromes (Joyce Reference Joyce2019), and imported Tohil Plumbate and Mixtec censer vessels. The four best preserved burials showed that the bodies had originally been placed in a seated position.

This novel burial posture is seen at Postclassic Las Flores Bolsa as well (Table 5). Here, a total of 14 Classic and Early Postclassic burials were excavated. Detailed burial records include field assessment of age and sex (Kidder and Strong Reference Kidder and Strong1936). The latest three were described as “bundle burials” in the published preliminary report (Strong et al. Reference Strong, Kidder and Drexel Paul1938). One of these contained poorly preserved remains of a juvenile, partly covered by an inverted pot. The two others, both assessed as adult females, were definitely buried in a seated position, like the majority from Postclassic Los Naranjos. Each of the seated burials at Las Flores Bolsa was accompanied by unique burial goods (Table 5). The new seated posture was also used in the sole Late Postclassic burial known from the Ulúa Valley from El Remolino (CR-260). Described as an adult, the body wore a necklace of tubular spondylus shell beads (Wonderley Reference Wonderley and Henderson1984). Two vessels were placed below the seated body, both painted in the typical red-on-white style of the period, Nolasco Bichrome.

The provision of assemblages of objects returns to an earlier practice of individuation of burials set aside during much of the Classic period. The shift to seated posture at the transition from Classic to Postclassic period removed the possibility of orientation toward the horizon, making a sharper break with tradition than in the transition from Formative to Classic period. A similar shift in burial position is noted at the same time in Belize (Pendergast Reference Pendergast1981).

Some materials included in these Postclassic burials suggest participation in new forms of ritual. Las Vegas Polychrome vessels and Nolasco Bichrome exhibit aspects of Mixteca-Puebla iconography, notably feathered serpent imagery (Joyce Reference Joyce2019; Wonderley Reference Wonderley, Chase and Rice1985, Reference Wonderley1986). This has been associated with a transcultural cult spread during the beginning of the Postclassic Period (Patel Reference Patel2012; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negron and Bey III1998). While the use of incense-burning vessels had a long history in Honduras, the incense-burning vessel of Mixtec style buried with an individual at Los Naranjos is, similarly, an indication of an association with an international ritual practice.

The same may be true of the inclusion in one burial at Las Flores Bolsa of a pot containing turkey bones, unique in the Honduran zooarchaeological record (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson, Joyce and Emery2004). Turkeys were an important part of ritual offerings recorded in Postclassic Yucatek Maya codices (Bricker Reference Bricker2007). Turkey bones were noted in burials at Postclassic Champoton (Götz et al. Reference Götz, Rubio-Herrera and García-Paz2016:649). They were used in ritual practices at Postclassic Mayapan, including at oratories and freestanding shrines (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Götz and Emery2013). Some freestanding shrines at Mayapan incorporated secondary skeletal remains. Analysis suggests these individuals include a cosmopolitan population originating outside Mayapan (Serafin et al. Reference Serafin, Lope, González, Kú and Wrobel2014:160). Secondary burial practices likely also continued in Honduras, where excavations at El Coyote, west of the Ulúa Valley, yielded a likely secondary burial context, a single bone buried with two Tohil Plumbate vessels and shell and jade ornaments (McFarlane Reference McFarlane2005:300–301; McFarlane Reference McFarlane2024). Rather than simple continuity in a local Ulúa tradition, Postclassic mortuary practices suggest an alignment with a cosmopolitan ritual identity expressed in mortuary rites.

Conclusion

The numbers of mortuary settings encountered in any one project are small. Our exploration of long-term regional patterning was only possible by combining information from heterogeneous sources, ranging from older unpublished field notes and brief publications, to more recently excavated and completely documented projects. The integration of different data sources allows a reconstruction of relatively stable practices in relation to the dead, with marked moments of change.

Initially treatment of the dead involved a cycle of moving remains from separate houses to collective ancestral caves. In house compounds, primary interments were personalized by wearing ornaments and the inclusion of distinctive objects. As some, if not all, the buried dead were relocated to ancestral caves, these personalized accompaniments were left behind. A collective practice of burial feasting was recalled by the deposition of serving vessels in some caves.

After centuries of similar practices, mortuary treatment shifted to a valley-wide pattern in which primary interments were united in their original locations by axial orientation to an ancestral mountain. In Classic period burials the dead were undifferentiated except for age. A cycle of secondary mortuary treatments continued, now in performances within sites where bones were displayed and redeposited in new configurations. These recall similar practices in Classic Maya sites.

In the Postclassic period, cosmological unity in the valley was replaced by a new cosmopolitanism. Burials again individuated persons. Some late villages employed mortuary practices that may have become familiar through an extensive network linking nobles asserting common connections to supernatural beings (Patel Reference Patel2012; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negron and Bey III1998). In these late burials, the dead were seated upright, aligning the body with the position of the sun at its highest point in the sky. This recalls the attempt made during the Classic period at one site, Travesía, to claim greater importance by adding solar alignments to traditional cosmological orientation to the ancestral mountain.

Over this long history, burial practices of the lower Ulúa Valley were coherent, although the region was never unified politically. The reproduction of practices points to a shared vision of the world, a philosophy, cosmology, or ontology that was resilient even in the face of confrontation with quite different visions of the place of humans in the cosmos held by neighboring peoples, as Maya and broader Mesoamerican elements were considered and selectively adopted. Layered memory was created through interment of both human bodies and meaningfully arrayed material culture. Memory was also created by disinterment and the afterlife cycles of humans as they transformed into ancestors via the transformation of bodies themselves (Lopiparo Reference Lopiparo, Gonlin and Reed2021).

Contrary to what might at first be assumed, it is not during the period when Classic Maya polities reach their greatest hierarchy that we see most engagement with practices originating in the Maya Lowlands. It is in the centuries equivalent to the Postclassic period that in the Ulúa Valley, participation in cosmopolitan rituals and social relations are reflected in changes in the treatment of the dead. We argue that throughout this long history, treatment of the dead was strategically manipulated by the living, in a ritualized tension between individualization and communal belonging that was the engine of social integration in the absence of overarching political authority.

Spanish summary

Este artículo presenta un análisis de los entierros y prácticas mortuorias en el valle inferior del río Ulúa en la costa norte de Honduras, desde el Periodo Formativo hasta finales de la época precolombina. Con base en contextos excavados en el sitio de Playa de los Muertos en la primera mitad del siglo XX y otros entierros encontrados en el mismo sitio en excavaciones más recientes, identificamos regularidades en el tratamiento de los muertos en el Periodo Formativo Medio (ca. 900–400 a.C.). Identificamos diferencias en el tratamiento de infantes y niños en contraste con los adultos. Sugerimos que los habitantes de la región practicaban un ciclo mortuorio que iniciaba con el entierro cerca de la casa de su familia. Detectamos el uso de una orientación preferencial del cuerpo del difunto dirigido hacia una montaña sagrada al sur del valle. Sugerimos que la extracción de elementos óseos para depositarlos en cuevas en las montañas, previamente notada en varios estudios de Honduras, fue parte de la conmemoración de los difuntos como ancestros de familias, y contribuyó a las relaciones sociales que vinculan a los pueblos autónomos.

La importancia de las ceremonias mortuorias en la integración de comunidades independientes continúa en el Periodo Clásico. Nuestras muestras nos permiten comparar prácticas del Clásico Temprano (ca. 200–450 d.C.) y del Clásico Tardío y Terminal (ca. 450–950 d.C.). El tratamiento de los muertos sigue patrones anteriores, con concentración de entierros alrededor de las casas, continuación de la posición extendida como postura preferida, y la presencia de entierros de niños y adultos. El tratamiento de niños y infantes fue diferente al de los adultos. Un cambio muy marcado es el abandono de la práctica de incluir vasijas, ornamentos, y otros objetos en los entierros. Las orejeras de cerámica son casi los únicos objetos encontrados en los entierros del Periodo Clásico. Sugerimos que es una indicacíon de un énfasis en el grupo, más que la celebración de individuos típica del Periodo Formativo.

Las orientaciones de los cuerpos de los difuntos hacia puntos de importancia cosmológica en el paisaje continuán. La muestra más grande, del Periodo Clásico Tardío, muestra que en cada sitio, la mayoría de los entierros estaban orientados hacia la montaña sagrada, o perpendiculares a ella, con un ángulo diferente utilizado en cada sitio para lograr uniformidad en la orientación. Sugerimos que se trata de un culto compartido a los muertos, asociándolos con los ancestros en la montaña. Un cambio con respeto al periodo anterior es la adición de una orientación alternativa, hacia el punto en el horizonte oriental donde aparece el sol en el solsticio del invierno. Sugerimos que esto es una indicación de cambios en la cosmología, con énfasis en el sol.

El entierro formaba parte de un complejo de prácticas de deposición estructurada en el ciclo de vida de las casas, junto con los depósitos de objetos y huesos humanos extraídos de los entierros. Bultos de huesos son sujetos del arte contemporáneo de la zona. La fragmentación de un cuerpo completo, humano o otro, y la extracción de elementos para su conservación o deposición en otros lugares, fue una parte repetida de los eventos que produjeron los depósitos estructurados.

La muestra de sitios identificados para el Posclásico es menor, pero provienen de contextos mortuorios que indican cambios en prácticas muy importantes. La práctica de incluir objetos en el entierro resume, una indicación de un mayor interés en la identidad individual. La postura preferida cambia: la mayoría de los entierros del Posclásico están en una postura sentada, con la cabeza orientada hacia el cielo—tal vez una indicación de un aumento en la importancia del sol en la religión.

Acknowledgments

Archaeological research in Honduras is carried out under the auspices of the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (IHAH). The authors would like to acknowledge former IHAH Directors, Dra. Olga Joya, Msc. Carmen Julia Fajardo, and Dr. Darío Euraque, former Assistant Director, Dra. Eva Martínez, and former Regional Directors, the late Lic. Juan Alberto Durón and Lic. Aldo Zelaya, along with the invaluable assistance of Isabel Perdomo, for their support of the research presented here. Jeanne Lopiparo gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for her research at CR-80, CR-103, and CR-381, which was funded by Individual Research Grant #6716, the Lita Odmundsen Dissertation Writing Grant, and the Richard Carley Hunt Postdoctoral Fellowship. Support for Lopiparo's research at Currusté was provided in part by Faculty Development Grants from Rhodes College. She would like to thank Doris Sandoval and David Banegas of the Museo de San Pedro Sula for their meticulous reconstruction of the figural incense burner from Currusté, along with the late Dra. Teresa Campos de Pastor, former Director of the Museo de San Pedro Sula, Dr. Rodolfo Pastor Fasquelle, former Honduran Minister of Culture, the Guifarro family, and, especially, the entire excavation team for their invaluable support of this research. Rosemary Joyce would also like to acknowledge the National Anthropological Archives for facilitating access to archival records related to the 1936 Smithsonian Institution expedition to Honduras.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Data Availability Statement

All our original data consist of collections and paper and digital archives deposited with the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia. Data from previous projects by the Smithsonian and Harvard are in those museums and in the National Anthropological Archives.