In 1549, after 11 years of slavery, and exile, an indigenous woman made it home to her people. In the time of her captivity, she became one of the most geopolitically important and well-traveled indigenous women in the Spanish Empire. Her name—or the name Spanish society gave her—was Madalena, and she returned home to Tocobaga, in what is now Tampa Bay. From bondage in Havana, she was taken to be the translator for a missionary expedition that sought to peacefully convert her people into citizens of the imagined Spanish colony of Florida.Footnote 1 That mission, like every other European attempt to settle the region up to the nineteenth century, would fail, but this latest failure of Spanish colonialism meant that Madalena could return to life among her own people, unlike most indigenous slaves of the sixteenth century.

Figure 1 Madalena greeting Cáncer in a 1950s Catholic tract

Madalena entered the Spanish colonial world, and the documentary record, as the captive of another failed conquest: the 1539 expedition of Hernando de Soto, who wandered from Tampa to Arkansas only to die on the banks of the Mississippi River. Madalena, spared that arduous journey, went from what is now the Florida Panhandle to become a slave in the home of Soto's wife, Isabel de Bobadilla. There she scrubbed pans, fetched water, and did whatever else was needed from a slave or servant living in that household.Footnote 2 As Bobadilla's criada (servant), Madalena traveled with the young widow to Seville, where her mistress pursued a lawsuit to save her dowry from her deceased husband's business partner. After the widow's death, Madalena drifted back to Havana, perhaps in the company of a fellow servant from the same household. There she drew the attention of the Dominican friar Luis Cáncer, a close collaborator of Bartolomé de Las Casas and the leader of the mission that would bring her home. Madalena knew Cáncer for only a brief time, but he placed a great deal of his hope for his mission on her. She taught him basic phrases in her language and made the world of local politics legible to him. After he helped her lead her own Christian ritual on a Florida beach, she disappeared from the written record.Footnote 3

Despite her feats of survival, her crucial role in the mission, and her miraculous homecoming, Madalena has no memorial, unlike the people who controlled her labor. Doña Isabel de Bobadilla is portrayed in the statue of the Giraldilla in the Castillo de la Real Fuerza in Havana, which is reproduced on bottles of Havana Club rum across the world.Footnote 4 A small plaque on the Catholic parish of Espiritu Santo in Safety Harbor, Florida, near Madalena's former village, commemorates the martyrdom of fray Luis Cáncer. Madalena's only memorial is her appearance as a secondary figure in a line drawing on the pulpy pages of a 1950s tract about Cáncer's martyrdom.

This is not a story about the vagaries of historical celebrity, nor, really, is it about Soto, Bobadilla, or Cáncer, except to the extent that they defined the trajectory and boundaries of Madalena's life, and that the documents generated in their historical wake help show us her experience. Just as a statue can be imagined by looking at the mold from which it was cast, I have drawn on these records and others to build a world around Madalena, a context that lets us see the historically invisible woman at the center of this story. In recounting her story, from her perspective, I argue that she and history's other displaced and enslaved indigenous people and their lifeways disrupt our conventional narrative of the so-called “Conquest Period” of Latin American history. They entangle connections between places long thought separate, shift our focus away from supposed centers of historical and historiographical activity like Mexico and Peru, and reveal to us the conquests that failed and the colonies that never were. Their stories show how inextricable indigenous people are from the larger narrative of conquest history. Madalena's story shows us the particular experiences endured and drawn upon by people forced to be cultural intermediaries, stretching back to the time before her captivity.

This reforming of the concept of narrative space around indigenous people depends extensively on the recent work of two historians, Nancy van Deusen and Elizabeth Fenn. Van Deusen in her book Global Indios proposes the idea of the “indioscape” as the space in which the broad category “indios” from Iberian colonies in the East and West Indies arose, through their captivity and presence as slaves in Spain and the larger empire. Fenn in her book Encounters at the Heart of the World makes the settled villages of the Mandan the narrative center of an alternative history of the Upper Plains, and more broadly of America. Drawing on Fenn's sense of narrative rootedness in indigenous spaces, I follow Madalena through her own singular “indioscape,” defined by the very real places she inhabited and the connections to those places that she brought along with her.Footnote 5

In telling Madalena's story, I draw on two decades of work to reorient and reappraise the roles of indigenous slaves and intermediary figures in the early colonial process. Authors working during this period have shown how inextricable the histories of men and women like Madalena are from the history and developments of the early colonial period. Authors like Frances Karttunen, Nancy van Deusen, Alida Metcalf, and Camilla Townsend have labored to put marginalized indigenous people, both laborers and interpreters, at the center of the story of the sixteenth-century Iberian empires. However, we have very few accounts of the lives of cultural intermediaries like Madalena and how they unfolded over time, or of how those experiences helped them frame and approach their intermediary status. The only major exception to this absence has been Karttunen and Townsend's work on Malintzin, the iconic translator for Cortés during the conquest of Mexico.Footnote 6 Madalena's story can therefore be an important addition to this body of literature.

The raw materials come from a rare series of opportunities afforded by the Tampa Bay region's many close brushes with Spanish colonialism, and Madalena's proximity to some of the more prominent citizens of the Spanish empire. Footnote 7 Despite the fact that Spain made no permanent settlement on Florida's Gulf Coast, there are nearly a dozen contact narratives recorded for the region, extending over a 60-year period.Footnote 8 When these are considered together with archival documents of the life of Isabel de Bobadilla, and of contemporary Havana and Seville, the picture becomes more detailed. Given the low status of an indigenous slave like Madalena in colonial society, it is only because of this outpouring of sources around her that I am able to tell her story, collecting fragments and mentions of a most often unnamed india in the sources.

When those sources do not exist, or when they remain silent, I am forced to cobble together a story from context. In truth, the Madalena of this piece may in fact be several women, each going through similar experiences, though I believe this not to be the case.Footnote 9 On questions of Tocobaga experience and belief, we must unfortunately rely on the words of their visitors and enemies, the Spaniards. Since the colonists of early South Carolina eventually enslaved the Tocobaga to work in their plantations, there are no direct Tocobaga descendants who can answer these questions.Footnote 10 The only words left from the Tocobaga language are the words Madalena taught Cáncer, “he oçavluata,” which he claimed meant “We are good men.”

Life in the Shadow of the “Mala Cosa”

Madalena grew up in a world that we can view only dimly, through the documents of her would-be conquerors and the glimpses uncovered by modern archaeology. The thatched huts of her village, its charnel house, its temple mount, and its fishing grounds all held meaning that she knew intimately, but that we can only infer. As she grew up in these spaces, news of bearded men loomed larger and larger, as rumors of their invasions spread into Florida's interior. Then one day, these men took her away.

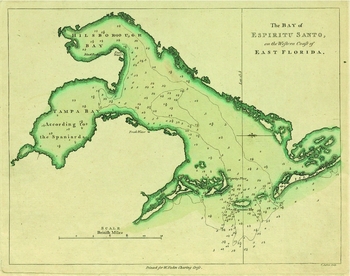

The culture that birthed Madalena emerged from hundreds of years of tradition, derived from local practices and Mississippian elements that came from the north.Footnote 11 The Tocobaga lived in and around Old Tampa Bay, the western lobe of the larger body of Tampa Bay, separated by the narrow neck of the Pinellas peninsula from the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 2). The head village, or at least its mound, lies in Philippe Park in what is now the town of Safety Harbor, facing the mirror-still saltwater of the bay. The Tocobaga were part of a broader grouping referred to by archaeologists as the Safety Harbor culture. They traded with Mississippian groups to the north and adopted some of their pottery styles and motifs, if not their intense focus on maize agriculture.Footnote 12 Most of their food came from the bay, which lapped at the edge of the village. The Tocobaga supplemented their catch with some maize from the interior, and some hunted and gathered foods as well. They had small seasonal fish camps, and, if their neighbors are any indication, great “corrals” made of piled shell and stone where mullet and other fish could be easily captured at low tide.Footnote 13

Figure 2 Tampa Bay, seen from the West. Tocobaga would be in the lower portion of “Tampa Bay according to the Spaniards.”

The Tocobaga were not alone in this world. To the south, below Charlotte Harbor, were their rivals, the Calusa, who controlled most of southwest Florida. The Apalache and Timucua lived to the north and east. In the northeastern bay, near modern-day Tampa, was the maize-producing village of Mocozo, which was a southern outpost of Timucua culture.Footnote 14 To the south of Mocozo, in the eastern lower bay, was Uzita, another Safety Harbor culture village. Beyond these known sites were dozens of villages whose names are recorded only in a manuscript list assembled by the Spanish castaway Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda: places like Cañogacola, Pebe, and Tampacaste.Footnote 15 Beyond fishing for sustenance, the Tocobaga and their neighbors gathered conch and whelk shells to prepare as cups for the great Mississippian ceremonial sites to the north. In return, they received flint and metal, both of which were entirely lacking in the area. They also gathered pearls, both to trade to the Mississippian north and to wear in great strands on their upper arms.Footnote 16 The Tocobaga must also have adorned themselves with ochre body paint, because Cáncer mentions off-handedly that his clothing had been stained red from their embraces.Footnote 17

Tocobaga today is a small point projecting into Old Tampa Bay, with a mound at the center. The buildings that covered this landscape can be inferred from a description of nearby Uzita: it “consisted of seven or eight houses. The chief's house stood near the beach on a very high hill that had been artificially built as a fortress. At the other side of the town was the temple [mesquita] and on top of it a wooden bird whose eyes were gilded.”Footnote 18 The Tocobaga lived in spacious communal palm thatch houses supported by large beams. Reportedly, one was so large that it could hold 300 people. Conquistadors who had lived in the Caribbean called these thatch homes bohíos, as the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean called their palm thatch houses.Footnote 19

Madalena was probably at least an early teenager by the time Spaniards captured her in 1539.Footnote 20 As she grew, so did the rhetorical shadow of Spanish presence in the circum-Caribbean. The first stories likely spread to her village when her parents were young, arriving along different information networks and trade routes and coming from several directions. As Spanish settlements in Hispaniola grew, the native population there shrunk. Spanish slave ships fanned out in all directions, snatching up people along the Atlantic coastline from Brazil to the Carolinas. Contact-borne disease may have followed in the wake of these raids. Whether through direct raids on Tocobaga, or through rumors of raids elsewhere, the Tocobaga began to learn about the Spanish.Footnote 21

The tenor of these whispered and repeated stories can be gleaned from a few tantalizing, if rare, narratives gathered from the northern rim of contact. Perhaps, as in the case of an anonymous indigenous informant from the 1540 Hernando de Alarcón expedition to the Gulf of California, this awareness began as a secondhand understanding that in some place distant from the Tocobaga homeland there were “other white men with beards like us [Spaniards].”Footnote 22 The beards of sixteenth-century Europeans seem to have made a lasting impression on indigenous people throughout the Southeast. When looking for a French settlement in what is now South Carolina in 1564, Spanish captain Manrique de Rojas reported that the local indigenous people made hand gestures representing beards as a shorthand for Europeans.’”Footnote 23

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca records more visceral and disturbing stories about contact that spread during his time in the Southwest. In southern Texas or northern Mexico, he came across an indigenous man wearing a Spanish buckle as a pendant. This man informed Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow travelers that men like them, with horses and beards and swords, had come and speared two people. After this, the bearded visitors had “gone to the sea and placed their lances under the water. They had also gone under the water, and afterward they saw them go above it [por çima] until sunset.”Footnote 24 These bearded men possessed special abilities, and they were clearly dangerous.

Cabeza de Vaca reproduces another chilling indigenous contact narrative that gives us some insight into the kind of fear experienced by indigenous people as their loved ones were captured by unfamiliar strangers. Although perhaps garbled by misunderstanding and mistranslation, or inflected with other local horror stories, Cabeza de Vaca tells of the coming of a person he calls the “Mala Cosa” (bad or evil thing). The Mala Cosa was a small man with a beard, whose face could never be fully seen. Around 1519, he came bearing a firebrand and a “long flint,” carrying away natives and wounding their upper arms in distinctive ways. Framed this way, it is easy to make the leap that Daniel Reff already has: that this story is in part a memory of a 1519 Spanish visit to Pánuco, as well as later slave raids led by followers of Nuño de Guzmán.Footnote 25 The “Mala Cosa” in this reading is a Spaniard wearing a helmet that covers his face and carrying a sword and a brand to mark his new property. This narrative is far stranger and less straightforward than a simple story of a slave raid, but it gives us an idea of the strangeness, inexplicability, and truly unsettling nature of such aggressive but fleeting early encounters.

In the early decades of the sixteenth century, when Madalena's parents were still young, tales and apparitions of this Mala Cosa became more frequent and more concrete. The Calusa, living just north of Cuba in the Florida Keys and Everglades, were closest, and therefore the first to know. Taíno refugees from the Spanish Caribbean came to settle among them, escaping the destruction of their native islands, just as they had in the southern Caribbean.Footnote 26 The chronicler Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas and the Calusa captive Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda both refer to Taínos settled among the Calusa. While Juan Ponce de Leon's ships waited outside of the Calusa head village, according to Herrera, a Spanish-speaking indigenous man approached the ship to offer gold and trade, just before a fleet of canoes assaulted the Spanish ship.Footnote 27 These Taíno refugees must have warned the Calusa about the Spanish, because they continued to be either wary or hostile to Spanish presence in the coming decades. When the Francisco Hernández de Córdoba expedition of 1517 gathered water in Calusa territory while returning from their failed conquest of the Yucatán, there was no pretext of trade: without warning, the Calusa attacked them with poisoned arrows.Footnote 28 Stories of the Calusas' success in warding off the invaders, told by these Taíno refugees, drifted north.

Around 1525, when Madalena was a baby or small child, Spaniards came to Tocobaga, but not as slave raiders or attackers. It was probably late summer, in hurricane season, and some forgotten ship had capsized on the return voyage from Mexico. The battered remains of the ship washed ashore, including large packing crates, bits of shoes and exotic feathers, and bearded corpses. This ghastly jetsam struck a chord among the Tocobaga. The burial of these objects is the first recorded story of the Tocobaga way of death; Madalena would later carry these ideas to Havana and use them to frame her views of Spanish religion.

To understand these burials, we have to jump forward to the late 1560s or early 1570s, when a few isolated folios describing Floridian funeral rites were hastily written, along with other notes. Eventually misplaced, they were collected in one of the many huge volumes of the Indiferente section of the modern Archivo General de Indias in Seville. John Worth believes them to be an excised portion of Escalante Fontaneda's report on the indigenous peoples of Florida to the king.Footnote 29 They discuss the funeral rituals of the indigenous peoples of south Florida at length. Our narrator describes the rituals of Tocobaga:

When a principal cacique dies, they cut him into pieces and cook him in some large pots. They cook him two days until the meat leaves the bones. They take the bones and place them in a box, one bone with another, until they are arranged as the man was [in life]. They put this in a house that they use as a temple. While they finish putting him together they gather together for four days, and at the end of four days the whole village gets together and leaves on procession, enclosing the bones and giving them much reverence. Later, they say that everyone who goes on procession gains indulgences.Footnote 30

What Escalante Fontaneda recorded was not just a ritual commemoration of the life of a powerful person but part of a deep and widespread funerary culture across peninsular Florida. Archaeologists have found large elaborate pots serving as containers for the dead, made hundreds of years before Madalena's birth.Footnote 31 In nearby Uzita, we know that bodies were also kept in boxes, where watchmen guarded them from predators and scavengers.Footnote 32 Safety Harbor-period skeletal remains show that the bodies were left above ground for many years, until the flesh left the bones, at which point they were buried.Footnote 33

Looking to the north, in a much later period, we get a view of what the boiling process for elite Tocobaga funerals might have meant. Amy Turner Bushnell summarizes the account of a seventeenth-century friar working in Apalache who recorded the story of the death of their mythical hero Nicoguadca, following on this request: “After I die, cut up my body and put it into cooking pots with squashes and melons and watermelons, and cover them with water and boil them well, that in steam I may rise up. And when you have fields I will remember you, and when you hear the thunder you may know that I am coming to bring you water.”Footnote 34 The boiling ritual formed a covenant between a departed leader and his people, who would remember him as he ensured the rain.

Madalena grew up with these stories and knew these kinds of religious and funerary practices. Though our Catholic informants frame these stories in terms of their own experience, they indicate that Madalena had ideas about the integrity of the body after death, group commemoration of the dead, and funerary practices that were very similar to those of the Spanish world. If the act of de-fleshing the body in water meant similar things for Apalache and Tocobaga, she would also have been familiar with a covenant involving water and renewal through death, echoing the stories of Noah and Jesus, as well as the ritual of baptism.

In an act of eloquent improvisation, the Tocobaga applied their rituals to the Spanish corpses that washed ashore, interring them above ground in the crates they had arrived with. Unfortunately, the Spanish could interpret this act only as diabolical. After landing with the 1528 Pánfilo de Narváez expedition, several Tocobaga took Cabeza de Vaca to “many crates belonging to Castilian merchants, and in each one of them was the body of a dead man, and the bodies were covered with painted deer hides,” along with the feathers, shoes, and gold that had also washed ashore.Footnote 35 Narváez, according to Cabeza de Vaca, ordered the crates burned, thinking that the figures represented some kind of witchcraft. Cabeza de Vaca, in hindsight, appeared to realize the mistake they had made.

The Spanish destruction of their own people's graves must have seemed like an utter rejection of Tocobaga hospitality, spitefully interrupting the long process of burial and rejecting the thoughtful inclusion of the gesture. It would not be the last time visitors disrespected the Tocobaga's wishes. When the Narváez expedition arrived in the Spring of 1528, bedraggled and hungry from the hurricane they had just endured, and far from their intended destination of Pánuco, the Tocobaga offered food for trade. But afterward, the inhabitants of Tocobaga, and of the other villages, fled. Meeting the Spaniards face to face, the Tocobaga demanded in words, then in gestures and signs, that the visitors leave. But they did not leave. The Spanish took four Tocobaga captive and demanded that they tell them where to find corn and gold. In the abandoned town, Narváez's men found a gold rattle, probably acquired from trade with the north. They must have pointed at it repeatedly as they interrogated their prisoners. The prisoners told these contemptible visitors—shakers of stolen rattles, demanders of scarce grain, and defilers of their own graves—to go north to Apalache, where gold and corn could be found. Perhaps Tocobaga parents taught children like Madalena to hide the gleaming rattles and other gold objects that so obsessed the Spaniards.Footnote 36 Indigenous people like the Tocobaga remembered initial moments of contact for decades and changed their “foreign policy” in direct reaction to these experiences.Footnote 37

The people of Uzita, apparently equally ill treated, had some small revenge. Their cacique captured Juan Ortiz, part of the rear guard of the Narváez expedition, using a false letter attached to a cross as bait.Footnote 38 The cacique sentenced him to death on a fiery scaffold. Before his execution, a female member of the cacique's household intervened, asking for a pardon and for Ortiz's acceptance into the group.Footnote 39 Given the duty of guarding the community graves, Ortiz fought off a large wolf or panther trying to abscond with the body of the cacique's son, which endeared him to the ruler.Footnote 40 Ortiz then went to live with the Mocozo for nearly a decade, carrying water and wood. Madalena grew up knowing about the strange man in the neighboring village, the foreigner who labored for them. Ortiz grew to understand his new life in Mocozo as Madalena grew to understand hers. For ten quiet years, the Tocobaga could ignore the bearded men. For ten long years, Ortiz waited for them.

These years of growing up Tocobaga shaped Madalena as she entered the Spanish world. Spaniards were likely still terrifying, but she could remind herself that her mother and grandmother had lived in their shadow as well. Besides these stories of boogeymen, she had also been taught what would happen when she died and where at least some souls went when they did so. She also knew how to work, helping to gather and prepare food, carrying water, and making and repairing the implements of a Tocobaga home. She would draw on these skills and re-learn them in her as yet unsuspected new life to come.

Taken

In late 1538, just months before Madalena's capture, three Spanish ships appeared and captured four men, leaving immediately. Hernando de Soto needed translators and informants for his entrada. Juan de Añasco, one of Soto's lieutenants and the contador (accountant) of the potential province of La Florida, brought the captives to Havana. Years later, while being deposed for a lawsuit, Rodrigo Rangel, his wife Catalina Ximénes, Alonso Martín, and Maria de Guzmán remembered the “testimony” of these four men. The four had held up maize, gold rings, and shoelaces with crimped pieces of gold at the ends (cabos de agujetas), and asked the Tocobaga if gold could be found where they were from. It must have reminded the four Tocobaga men of the kidnappings and obsession with gold they had seen a decade before.

All of the Spanish deponents agreed that these four men had answered yes to the questions, and Rangel remembered the delight of the would-be conquistadors at this news. Guzmán recalled that the four men declared the news publicly (publicaron). Only Ximénes remembered what her husband had forgotten: that these men communicated only by signs (“davan o dezian por señas”).Footnote 41 Newly captured and scared, they told the Spanish as best they could that there was gold and corn to the north, perhaps hoping to return home. As the men thought of home, the Tocobaga wondered where it was that they now found themselves.

Months later, the bearded men returned to Florida by the hundreds, making landfall near Uzita and marching under the command of Hernando de Soto. Plumes of smoke rose up and down the coast as the local people warned each other of the arrival of the strangers. Poorly guarded, the four indigenous men escaped. Upon finding them gone, two raiding parties fanned out. One party, under Baltasar de Gallegos, found Juan Ortiz stuttering with fear and struggling to remember his native Spanish. Another party, under Captain Juan Rodríguez Lobillo, went into the interior, where they captured several women.Footnote 42 Madalena was likely one of them.

The Tocobaga fought fiercely to get Madalena and their other people back. Perhaps remembering the four men, perhaps also having heard their stories, the Tocobaga sent out a party to try to retrieve them, moving fast and light through the woods and pelting Lobillo's men with arrows. Rangel, the author of one of the primary accounts of the expedition, devotes nearly an entire page to their valor.Footnote 43 Despite killing one man, and wounding several others, they did not succeed in getting her or any of the other women back.

Madalena's captors placed her in a hut in the newly ravaged village of Uzita, whose buildings had been demolished to make temporary huts for the soldiers.Footnote 44 For a distance of two arrow shots in every direction, the ground was nothing but stumps, bedraggled vines, and wood chips. The Spanish had cut everything down to deny the people of Uzita cover if they tried to retake their village. Europeans often branded slaves after capture, although there is no reference to Madalena being branded in later documentation.

Lobillo's raid was not the last. The ranks of captives grew, albeit more slowly than Soto and his men wanted. These men were experienced slavers. Soto, in addition to helping conquer Panama and Peru, had been the owner of a slave ship in Central America.Footnote 45 Former Cuban colonial official Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa left, frustrated by the failure to capture more slaves and quarrels with Soto.Footnote 46 The Tocobaga took a Spanish man named Juan Muñoz, perhaps as revenge for Madalena's capture.Footnote 47

Madalena's road to Havana is unclear. Later texts that mention her origins elide this information. Prince Philip, relaying the contents of a letter sent to him by Isabel de Bobadilla, says only that Madalena and two men "were taken to her [from Florida].”Footnote 48 Cáncer mentions in a letter that a pilot named Juan López recalled bringing three men and one woman “of the coastal language” to Havana on the orders of Hernando de Soto, but he does not mention López's port of origin.Footnote 49 Madalena once stated that she was from Tocobaga, but nothing more is recorded. The four main chroniclers of the mission give next to no attention to the lives of women.

Given these silences and the accounts in the chronicles, we can construct a likely sequence of events. Displeased by the lack of gold and human capital to be found in Tampa Bay, Soto and his followers turned north towards Apalache, where they had heard there were large supplies of maize and gold. A small rear-guard garrison of 60 footmen and 23 horsemen remained at the camp at Uzita, and Madalena remained with them, since they needed local interpreters and laborers to supply them.Footnote 50 They remained there until the early winter, when Soto prepared to leave for the north. Juan de Añasco returned by ship to order the garrison to head north as quickly as possible, traveling lightly.Footnote 51 When these men arrived in Apalache in early 1540, Soto sent a ship captained by Maldonado back to Havana. Aboard the ship were several indigenous slaves Soto was sending to his wife to enrich their household and to learn Spanish, and Madalena was likely one of them.

Madalena spent the traumatic early months of her captivity only a few miles from her home, cooking the same foods and seeing the same mangroves, beaches, and pines as in Tocobaga. But there was also laundry to do, a new language to learn, a captivity to mourn. Then, there was a hard march north, where she witnessed a great deal of violence and where her work became more necessary to the functioning of camp life. She lived in constant danger and uncertainty. As the Gentleman of Elvas relates, “there, as well as in any other part where forays were made, the captain selected one or two for the governor and the others were divided among themselves and those who went with them.” In the terror and dislocation of these camps, with the constant threat of rape, in the creaking holds of the boats she traveled in, Madalena entered a much larger and more threatening Atlantic world.Footnote 52 She may have learned to prepare corn from women from northern groups she had only heard of. She may have been forced into the bed of the Spaniards she had only heard about until then. She learned her first words of Spanish and saw horses for the first time. In an atmosphere of sexual violence and hard labor, Madalena joined the fellowship of thousands of women uprooted by an expanding empire, and went down to Havana by ship to live among her captors.

In the Governor's House

Madalena's transition from Florida prisoner to Havana slave is unknowable, but we can speculate on her experiences. Van Deusen argues that however disruptive their imprisonment and assault was, the partnerships between conquistadors and their sexual partners set the tone and contours of early colonial life.Footnote 53 Yet Madalena's time in a female-run household must have been a significant disjuncture in this experience. Bobadilla, her new mistress, may have been vicious and cruel, but Madalena was no longer chained, or hurried along the road, or subject to the depredations of many strange men.Footnote 54 She may not have been safe, but life in Havana was less tumultuous than in Florida. In her transition from newly imported pieza to criada of the household, did she think of Ortiz as a model for life as a servant among strange people?

Havana was one of the many Caribbean cities drained of colonists who had left to conquer places like Colombia, Florida, and Mexico. Far from the major Atlantic port it would become by the end of the century, it was a sleepy entrepôt.Footnote 55 In the testimony mentioned earlier, former settlers estimated that the village had no more than 15 to 20 vecinos (heads of household), in part because French corsairs, visiting Havana on their way from raids in Panama, had recently burned the settlement to the ground.Footnote 56 Diego de Sarmiento, the bishop of Santiago de Cuba, passing through Havana on an inspection of the island in 1544, declared that the settlement had 40 married and unmarried European men, 120 local Taíno naborías (Taínos bound to servitude, but not technically slaves) and 200 indigenous and African slaves.Footnote 57 Regardless of the precise numbers, Havana was an indigenous and African community far more than it was a Spanish one, and those Taíno, their fellow indigenous slaves from other parts, and Africans would constitute the majority of Madalena's friends and social contacts.

As to the physical setting of Madalena's captivity, the Gentleman of Elvas describes the island of Cuba as a fecund wilderness overrun by the plants and animals of former settlers; overgrown with plantains, guava, citrus, and cassava; overrun with cattle and pigs so numerous they made their own roads; and filled with packs of newly wild dogs that stalked them.Footnote 58 Irene Wright describes the countryside around Havana as a place where settlers hunted cows instead of raising them, turning them into jerky for Spain's fleets.Footnote 59

If the land itself was giving and rich, the encomenderos, the indigenous men put to labor by the crown, were not.Footnote 60 The Taíno, despite their large and continual presence during Madalena's time in Havana, were only a remnant of their former numbers. The enslaved indigenous people around Madalena were a diverse community whose members came from as far north as present-day North Carolina and as far south as Brazil.Footnote 61 Many of these were Maya from the nearby Yucatán and captives from elsewhere in the Caribbean.Footnote 62

Isabel de Bobadilla was among the most well-connected and elite women in the Americas. Her contemporary, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, despite his apparent disdain for her husband, described her as “a woman of great worth and goodness, of courtly judgment and personage.”Footnote 63 Newly married to the adelantado of Florida, who was also a conqueror of Peru, she brought livestock, property, and income from Panama and Tierra Firme into her marriage through her inheritance.Footnote 64 She was the daughter of Pedrarias Dávila, former governor of Tierra Firme.Footnote 65 She was also well connected to her husband's men and their wives, having known several of them since childhood.Footnote 66 In her husband's absence, she became acting governor of Cuba and looked after his property there. She also housed at least four of the wives of elite conquistadors, one of whom was pregnant.Footnote 67

Bobadilla administered the island of Cuba as well as her own house, dealing with murders of prominent citizens, problems with the bishop, and the like, and in her husband's absence completing a new fort to guard the harbor.Footnote 68 She also had her husband's business partner, Hernán Ponce de Leon, arrested for financial crimes, sparking a series of legal struggles between them that would continue for over a decade. In this busy house, teeming with people and with power, Bobadilla desperately needed Madalena's labor. Even as Madalena adjusted to the shock of her second dislocation, Bobadilla forced Madalena to attend to the problems and needs of her owner first.

When Madalena arrived at what would be her home for the next three years, she found a compound of two thatch-roofed houses, one for Bobadilla's household and one for storage, “bounded by mayor Francisco Cepero's house on one side, and by Juan Marqués's house and public streets on the other.”Footnote 69 There, she became enmeshed in the indigenous and African slave community of Havana, forming a circle of acquaintances.Footnote 70 Madalena met the African slaves Joanillo and his wife Francisca and Manuel, Domingo, Hernando, Jorge, and Julián, along with a few of their children. Bobadilla had brought with her at least three “esclavas blancas” (morisca or North African slaves), including one named Isabel who worked as a personal attendant to her namesake.Footnote 71 As simultaneous insiders and outsiders to Spanish life, did these Africans and moriscas sympathize with Madalena's sense of displacement? Despite the babel of tongues and the great mix of peoples, this village was not so different in size or appearance from the one she came from, a cluster of thatch houses huddled by an interior bay. Even the ubiquitous lizards of the tropical midday, bobbing their heads and puffing their throats, were similar, although in Cuba they were brown instead of green.Footnote 72 The space between the two houses was open to the world, and she and the servants, allowed some mobility, could make connections with the people of Havana.

Confronted with these many new faces, and forced to work as a member of a household whose people she barely understood, Madalena rapidly learned about the Spanish world. She learned the finer points of Spanish, becoming quite fluent by the time of the Cáncer expedition. A later investigation concluded that she had been “indoctrinated in our Holy Catholic Faith,” which meant she knew at least her basic prayers.Footnote 73 In the storeroom and the main house, she was surrounded by Catholic material culture—devotional prayers to the Virgin Mary, rosaries, a crucifix, a baptismal font, and a set of vestments for mass that were kept in the house and presumably used there.Footnote 74 She attended mass in the one thatch bohío church of Havana with its one parish priest, not so different from a Tocobaga home, at least architecturally. Stone churches did not yet exist in the small village of Havana.Footnote 75 If she was baptized after her arrival, it may have been at the same font that stood in her home, or the one in the bohío church, under the watch of the same priest who said mass every Sunday.Footnote 76 If Bobadilla stood as her godmother, she would have been Madalena de Bobadilla, marked as both property and as family in a three-word pronouncement, a clumsy assemblage of syllables as ill fitting as her new Spanish clothes.

What Christianity meant to her is impossible to know. Perhaps, with their emphasis on processions, boxes, and supplication, all of them elements found in Tocobaga funerals, Castilian funerals held a special resonance. She would have reason to attend many of them during her captivity. Perhaps, to return to the story from Apalache, the death, resurrection, and covenants of Catholicism made a certain amount of sense. She certainly learned the style, whether or not she embraced the substance, of mass and the appropriate way to adore the cross. When she was with Cáncer, she knew when to kneel during the recitation of the litanies. She could also lead her own rituals, as she later did in Florida. Perhaps, like the Latin prayers she memorized, Castilian religion was merely rote action rather than belief. Or perhaps a deep form of solace in a chaotic life.

As Madalena settled into life in exile, the needs of Isabel de Bobadilla and her guests dominated her life: their baths, their laundry, their meals, their crops, whatever it was that needed doing.Footnote 77 Madalena and the other captives learned the uses and care of a bewildering array of new items. They learned to prepare cassava, polish copper and silver, and care for nearly every kind of fabric imaginable. Bobadilla's storerooms overflowed with worked silver from her dowry, plus velvet, wool, silk, linen, bedding, hoop skirts, leather, and tapestries. There were also swords, artillery, pots and pans, and bits and bobs of high-end goods, ranging from civet perfume and pearls to gold nails.Footnote 78 This new knowledge was key to Madalena's success in her new home. If she could remove wine stains from dresses, dab just the right amount of perfume behind her mistress's neck, and make good bread, she would become a valuable member of the household.

Adrift in the Atlantic

Madalena probably had little choice in beginning the second sea voyage of her life, enmeshed as she now was in adopted networks of kinship, labor, and dependence.Footnote 79 The only indigenous people who came to Spain entirely of their own volition were high-ranking elites seeking concessions or diplomatic agreements with the king. Indigenous servants like Madalena became vital portions of the family unit, and traveled with it. If Isabel de Bobadilla had to return to Spain, so did her servants.

Madalena boarded a ship as part of Bobadilla's retinue in early 1543, but the immediate cause of her second journey was the death of Hernando de Soto on the banks of the Mississippi in 1542. Word of his death slowly travelled back to Bobadilla, and when it arrived, she arranged her affairs, sold her husband's property in December of that year, and left the following spring.Footnote 80 Rodrigo Rangel, one of the chroniclers of the expedition and the husband of one of Bobadilla's houseguests, bought the property. Madalena, Isabel the morisca, and other members of Bobadilla's entourage made the long journey back to Spain. Bobadilla intended to resettle in the Castilian city of Segovia, where she had grown up, and where Madalena would live out the rest of her years in her service.

For the second time in five years, Madalena reckoned with a new place. She would be among some of the members of her household, but even farther away from her original home. Unlike her time in the open spaces and thatch houses of Havana, her work in Seville kept her in airless interior kitchens and household courtyards, where the interior balconies of the second story provided a vantage point from which her work could be observed. The sheer size of Seville likely exhausted her, as the similarly sized city of London exhausted European and indigenous visitors in later centuries.Footnote 81 Perhaps, like Inuit visitors to London, she compared Seville's outsized cathedral to familiar things: to the large meeting houses of her youth, or to the arcing branches of ancient live oaks.

Bobadilla, watching Madalena from above, became embroiled in a series of legal proceedings. Upon their arrival, the officials of the Casa de La Contratación (Board of Trade) confiscated the worked silver that constituted part of Bobadilla's dowry, silver that Madalena had likely polished. Officials thought it was undeclared wealth.Footnote 82 This same inspection threw Madalena and the two Florida men into legal limbo, since their arrival violated a 1543 law that banned the importation or migration of indigenous people from the Americas to Spain.Footnote 83 Bobadilla, if found guilty, would have to pay the full cost to return Madalena to her home province as well as a 100,000-maravedí fine. If Bobadilla was found to be abusive, Madalena and the two men would be put in protective custody (depósito) in a stranger's house. Further, indigenous slavery had been outlawed in 1542.Footnote 84 The wrinkle, however, was that Madalena was from a province that, from a Spanish legal perspective, did not exist. Madalena could dream of the return home and perhaps was even told that it was a possibility, but she had to wait on the decision of the prince and of the Council of the Indies. Meanwhile, she tended to Bobadilla, and to her temporary home.

Prince Philip, the future king, took notice of Bobadilla's many legal troubles in February 1542, and began to issue letters to resolve them. The case of Madalena's freedom, and her proper place in the Spanish empire, would take three more months to resolve. On February 7, Prince Philip asked that Bobadilla's silver be returned, since it was her property.Footnote 85 Philip issued a summons on Bobadilla's behalf, inaugurating a nine-year case against her husband's former business partner, now a councilman (veinticuatro) in the city of Seville.Footnote 86 Finally, on May 7, Philip dealt with Madalena's legal quandary. Bobadilla had informed him that three Florida natives had been living in her house and had been properly instructed in the faith. The prince decided that Madalena and the two men would better serve the empire as potential translators, and that to allow them to return to their homes in Florida would be to lose an important piece of the crown's property. And, the prince added, there was no province of Florida to send them to.

The prince ordered the officials of the Casa to verify that the Floridians were not slaves and to give them back to Bobadilla, who would hold them in trust until the empire had need of them again.Footnote 87 Technically, this freedom hearing was about Madalena's rights as an American indigenous person in the Spanish empire.Footnote 88 She would have testified before the judges of the Casa, but these proceedings, and their judgments, are lost. She remained in the house of her former owner but her body no longer belonged to Bobadilla; her mind, and the knowledge she had worked so hard to gain in the last six years, were now property of the Spanish state.

The special treatment of displaced persons as royal patrimony was an Iberian tradition, dating back to early Portuguese expansion into Africa and continuing through the intervening decades. The twin programs of penal exile and kidnapping of potential interpreters that emerged on the African coast had developed into a rich tradition by the time the Portuguese settled in Brazil.Footnote 89 In the early years of the Spanish colonies, high-ranking indigenous people and slaves from new frontiers were taken to Seville or Spanish cities in the new world with the specific aim of educating them in the basics of Spanish and Catholicism, often under the eye of Spanish clerics or nobles. Given the scale of indigenous slavery in the preceding years, and the number of elite indigenous pupils and visitors in the city, Madalena likely met even more diverse indios, some coming from Portuguese East Asia.

Madalena faced lonely and trying years after her day in court. Bobadilla died in 1546, and how Madalena returned to Havana is a mystery. She may have traveled with Isabel the morisca, who in 1546 returned to her husband in Havana, along with her children.Footnote 90 If she did remain in Seville, Madalena would have risked being re-enslaved. Once separated from their original masters and social networks, indigenous servants often struggled to prove that they were either indigenous or free.Footnote 91 Whether in Havana or Seville, she would have to draw on her existing connections (perhaps to Bobadilla's mother and sister in Spain) to survive, likely continuing her work as a domestic and personal servant in houses in Seville or Havana.

By the time Madalena returned to Havana, Luis Cáncer was struggling to find a translator for his mission. He wished to bring about a peaceful conversion of the indigenous peoples of Florida and bring them into the Spanish empire, and a translator was key to these persuasive efforts. His frustrations emerge in his correspondence with his mentor and former supervisor, Bartolomé de Las Casas. Cáncer had met several Floridians during his mission work in Guatemala, brought there by survivors of the Soto expedition.Footnote 92 None of these people could be found. In a series of long meetings with Cáncer, Juan López, the former pilot of the Soto expedition, revealed that he had taken four Floridians to Havana. A man named Santana informed Cáncer that only one woman, presumably Madalena, remained. Cáncer, whether concerned about propriety or filled with sexist doubt about Madalena's ability, wrote that he would not bring her with him “for all the world.” Footnote 93 At the behest of his colleagues, and because he could find no male translators, Cáncer eventually relented.

These letters, beyond fleshing out Madalena's story, reveal a startling truth that must have weighed on her through these years: Madalena was the only indigenous person from the coast of Florida left in the Spanish empire. The men who went to Spain with her were gone; they had died in the previous two years. She had not met the Guatemalan Floridians, but the other Floridians in Havana were also dead or gone. Her mistress was dead, and the rest of the Bobadilla family remained in Spain. Beyond Isabel the morisca, and other acquaintances in Havana, Madalena was radically alone. Whether or not she had much choice in the matter, she was faced with an opportunity to leave her life of service and isolation and to use her knowledge of Spanish religion and the Spanish language. If she believed fervently in her new faith, it was an opportunity to work on behalf of her new God, and to spread his ways to her people. Most importantly, it was a way back to a more familiar place, and possibly even to her former home.

Madalena la Lengua

In keeping with Spanish practices at the time, Cáncer wrote Madalena out of the narrative he constructed about his mission to Florida. In his rendering, Cáncer communicated directly with the people he encountered, rather than speaking through Madalena.Footnote 94 Still, she emerges between the lines and in small details. Madalena had only a few days to teach the friars some basic words in her language, and she taught her pupils a particular phrase—“he oçavluataI”—that according to Cáncer meant “we are good men.”Footnote 95 In light of her childhood, and the depredations of the Narváez and Soto expeditions, this phrase (if it meant what Cáncer thought it meant) seems especially useful. If she believed in the content of the mission, he oçavluata served as a kind of Tocobaga talisman, a way to confirm that these Spaniards were different from those who might have violent aims.

After ten years abroad, Madalena came home, or very close to it. The expedition had spent days searching for the entrance to Tampa Bay, when the shallow water of the Gulf forced the crew to reconnoiter the coast in a smaller boat. Even a mile out at sea, the Gulf could be only six feet deep. For days, she could see land tantalizingly close to her home, even sleeping on an island just off of the coast. Finally, after those long days, she stood on the shore with fray Diego de Tolosa and a hired hand named Esteban de Fuentes, who had volunteered to see if the Tocobaga were hostile.Footnote 96

After the expedition made landfall, Madalena became the translator the prince had selected her to be. Cáncer came up behind her as a crowd of Tocobaga gathered, and she fell to her knees on the beach next to her new employer as he read the litanies from a book. Her people kneeled and lay down around her, perhaps following her lead. They moved to what Cáncer recorded as a barbacoa, in this case likely a grate for smoking fish, where she began speaking on his behalf. She figured out where the entrance of the bay was, trying out the words of her language for the first time in several years. She told the Tocobaga of Cáncer's “intents and desires” to preach among them, peacefully. Or perhaps she had her own words to say. As Cáncer began to distribute some small gifts, she pointed out the brother of the chief so that the gifts could be given to a native leader to distribute. Perhaps she remembered this man from her childhood, or perhaps she spoke to him in her language. Before Cáncer left, Madalena “seeing such peace, was very happy, and said to [him], ‘Father, I didn't tell you, that as I spoke to them, they won't kill you. They are from my land, and this is from my language.’”Footnote 97 Cáncer left her with the two friars to translate for them until the ship found the entrance to Tampa Bay.

At this point, several days' events are missing from Cáncer's account. Madalena settled into life back at home. She walked inland, across the peninsula and onward to the bay, to the village where she was raised. In the heat of June, she shed some of her clothes. Cáncer, the next time they met, remarked that she was naked, but “naked” to a contemporary Spaniard meant anything shy of the normal standard of Spanish dress.Footnote 98 She may have just taken her top off. Without these clothes, the heat of the dry season was less stifling, and she looked more like a Tocobaga. She spoke her language at length, perhaps for the first time since her male companions had died. Perhaps she saw her parents, or cousins, or childhood friends.

What she did during the eight days she waited for Cáncer is unclear, as is what happened to Fr. Tolosa and his hired hand Fuentes. The Tocobaga captured a sailor soon after Madalena went inland, but we hear nothing more of him. Later, Madalena said that the Tocobaga and their neighbors had prepared for war, fearing another entrada. An odd bit of text, embedded in a later history of the Dominican order, narrates this time from the perspective of Juan Muñoz, the Spanish man captured by the Tocobaga the same year Madalena was taken. Muñoz, or his ghostwriter, says that after seeing the ships, the Tocobaga sent up smoke signals, meaning to oppose the Spaniards who had so harmed them in the past. Because of this, when the friars came, they were killed, and their heads hung from trees by cloths.Footnote 99 Our narrator makes no mention of Madalena.

Madalena told Cáncer her own version of events on his return, in a meeting he describes in detail. She took a cross from him and went from person to person in an assembled group of Tocobaga, offering it to them for them to kiss. Concluding her ritual, she stood with the cross in front of the assembled crowd, an act that caused Cáncer to beam with pride.Footnote 100 She then returned to speak with him. She told him that his friends were alive in the house of the cacique, and that she would not lie about that. The Tocobaga, and their neighbors, readied for another war with the bearded strangers, but Madalena said that she had told her people that the Spaniards were only a few friars who had come to preach, and that she had gathered this crowd to hear their message.Footnote 101 Cáncer then left after giving out more gifts. In both versions of the story, Madalena came home to a Tocobaga full of anxiety and hatred of the men who had taken her and then returned with her. Either the friars were alive when Madalena last saw them, or she knew about their murder but kept it secret.

When Cáncer got back to the ship, Juan Muñoz was there, carrying a Spanish scalp. Muñoz said that two Spaniards were dead, and another was still a prisoner. Cáncer, days later, saw another group of Tocobaga. Using whatever crude señales he could muster, he asked for Madalena, and in equally crude señales, they told him she was in a house, far away. As Cáncer waded ashore, hoping to continue the mission alone, one Tocobaga man embraced him and another bludgeoned him to death. Fray Gregorio de Beteta, Cáncer's companion on the mission, finished the journal and added the entry describing his murder.Footnote 102

Whether Madalena had betrayed the mission or not is hard to infer. In Cáncer's narrative, Madalena is made out to be an enthusiastic and pious helper, eager to prove the spiritual abilities of the Tocobaga. However, from the anonymous Dominican account mentioned earlier, it seems clear that Madalena knew that Cáncer was in danger, and that his fellow priests were dead. She certainly would not have been the first to “betray” a mission. Francisco el Chicorano, an indigenous man from the Carolinas, managed to convince Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón of the riches of his homeland. Upon arrival, Francisco promptly left the expedition and led the opposition to it.Footnote 103 Several of the translators kidnapped by Añasco ran off as soon as they had the chance.Footnote 104 Anna Brickhouse describes the life of don Luis de Mendoza, an indigenous man who convinced the Dominicans (Beteta among them), and then the Jesuits, that the Chesapeake Bay was ripe for conversion. He, or his allies, later turned against the missionaries. Brickhouse reminds us that willful mistranslation and lying was itself a weapon, used by colonial intermediaries and every bit as important as the faithful translations of Malintzin and others.Footnote 105 It was a weapon available to Madalena, whether she chose to wield it or not.

The Tocobaga, or portions of them, rejected the Spanish, even if they were only two priests. Madalena's stance is more ambiguous. Perhaps Madalena believed in the mission, and sought its continuing success. In Cáncer's rendering of her actions and words, she seems to have believed in the goal of conversion and in her new god. Another Dominican chronicle, almost certainly apocryphal, claims that the murder of the two friars and the failure of the mission so saddened her that she could hardly bear to look at Florida.Footnote 106 Another possibility is that she already knew that Cáncer's men were dead when she spoke with him that last time, and laid a well-set trap. Perhaps she sought to ensure that men who looked like him, and like the men and women who had kidnapped her, raped her, shipped her about, ordered her around, and laid claim to her body, mind, and soul would never come back. Perhaps, more simply, she decided to go home.

Conclusion

The true end of Madalena's story must remain untold. On her return to the place of her birth, she departed from the historical record. No subsequent visitor to Tocobaga mentions her. What is certain is that Madalena made the place again her home, despite every probability that she would not. She lived ten years, a little less than half her life, hemmed in by Spanish society, cowed by violence, threatened with rape, surrounded by foreign pathogens, and forced to labor for others. She spent her childhood in Tocobaga afraid of those who eventually enslaved her, and perhaps of their diseases. They took her from Florida, to Havana, to Spain, then back to Havana, and back to Florida. She had been a camp follower, a slave, a servant, and an intermediary. Yet despite these constraints and dislocations, she succeeded at being a valuable member of a household, at learning Spanish, and at adopting foreign religious symbols. She succeeded, however briefly, in using this knowledge to be the sole translator for a major expedition that attempted to convert rather than conquer. Either she succeeded at worshipping her new god in her native context, or she performed piety so convincingly that it was a tool of revenge. Only she knew.

In looking at Madalena, we see a survivor who tenaciously sought connections between her past and her present, and between her world and that of the Spanish. We also see worlds long ignored or shut off from the conventional realm of conquest history, worlds that had almost nothing to do with the affairs of prominent conquistadors or colonial centers. We see how a village at the edge of the sea reckoned with invaders, seen and unseen, and how that place avoided being swallowed up by the Spanish. Along the way, we came to see Havana as an indigenous and African space, with a small and tenuous Spanish presence. We saw the mission field as a place where translators were among the most powerful and influential persuaders. We also saw many smaller moments ignored by that same history of conquest in the circum-Caribbean: the impromptu indigenous funeral of a lost and anonymous Spanish crew on the shores of Tampa Bay; the administration of an island and a household by a gobernadora; and the slave Isabel the morisca reuniting with her husband and children in Havana. As we shift the narrative of the conquest away from battlefields and into the personal indioscapes of enslaved indigenous people, what other histories of the period will be revealed?