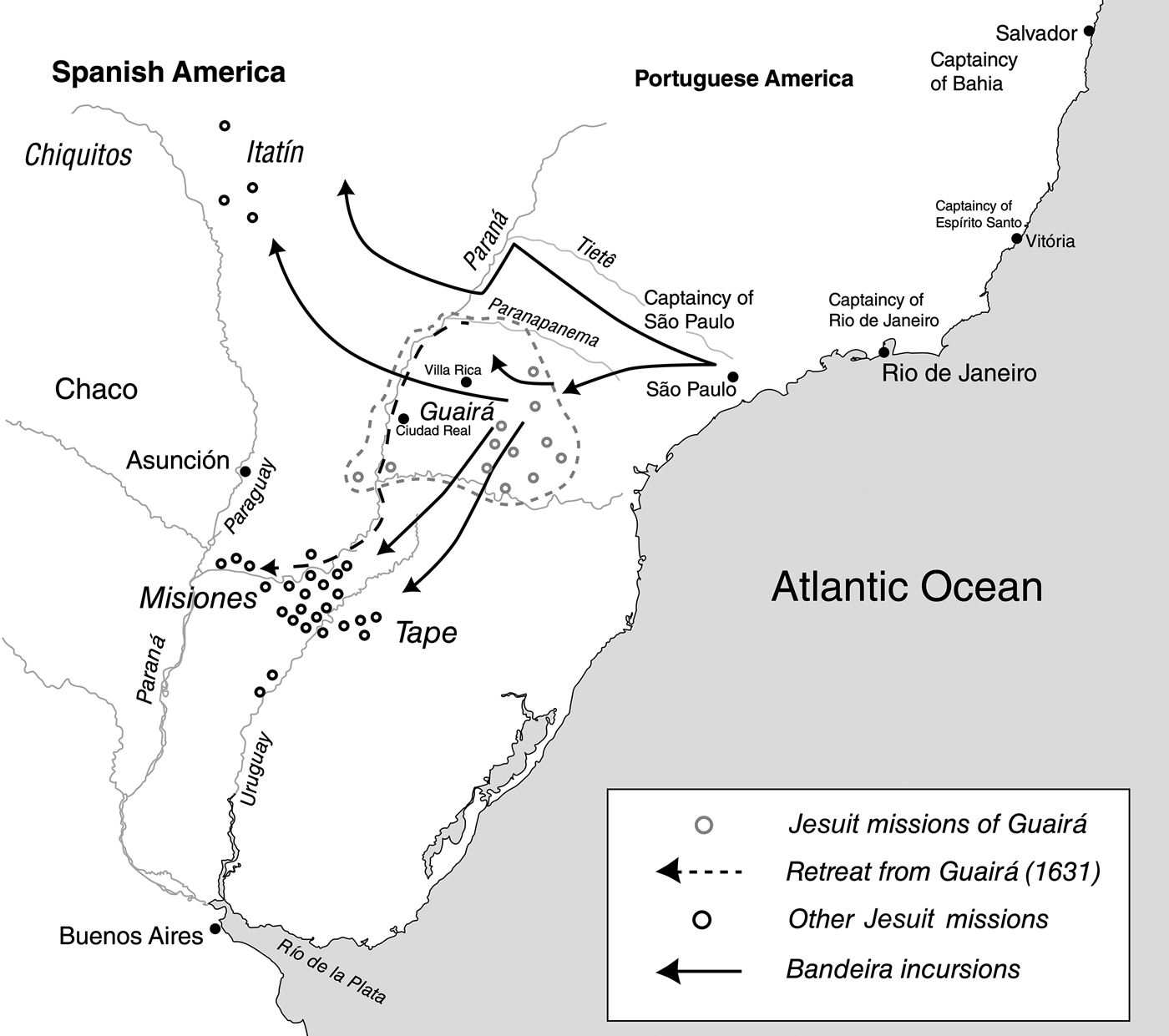

Jesuit activities among the natives of Paraguay began in 1609, when Governor Hernando Arias de Saavedra invited Father Diego de Torres Bollo, provincial of the Society of Jesus in that province, to establish missions among the Guaraní.Footnote 1 On December 29, the Jesuits founded the pueblo of San Ignacio, their first mission in the Guairá region. Spanish authorities understood the Guairá as a separate frontier jurisdiction east of Paraguay, roughly delineated by four rivers: the Piquiri, Paraná, Paranapanema, and Tibagi (see Figure 1). Spanish colonists had been present in this region since 1556; however, a group of conquistadors, convinced that they had been overlooked in the distribution of encomiendas in Asunción that year, decided to seek better opportunities to the east.Footnote 2 Two of the cities they founded, Ciudad Real and Villa Rica, achieved a certain stability by relying on Guaraní forced labor.Footnote 3

Figure 1 Portuguese Incursions and the Jesuit Missions of Paraguay in the Early Seventeenth Century

Source: Own elaboration adapted from John Manuel Monteiro, Negros da terra: índios e bandeirantes nas origens de São Paulo (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1994), 13; Brian Philip Owensby, New World of Gain: Europeans, Guaraní, and the Global Origins of Modern Economy (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021), 132; and Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Atlas Histórico do Brasil, https://atlas.fgv.br/marcos/igreja-catolica-e-colonizacao/mapas/missoes-jesuitas-na-bacia-do-paraguai. Artwork by Sanjay Dutt.

Franciscans began evangelization efforts in the Guairá in 1580, but Spanish authorities decided that the Jesuits were a more appropriate choice to mitigate encomendero influence in the region and defend it against the Portuguese.Footnote 4 The Jesuits began their work at a very complicated time, after Francisco de Alfaro, an inspector sent by the Audiencia of Charcas in 1611–12, imposed important limits on encomenderos’ exploitation of native laborers.Footnote 5 Since the Jesuits advanced rather quickly, founding 13 missions in Guairá between 1610 and 1628—the priests claimed to have reached more than 40,000 natives—scholars debate the reasons why the Guaraní accepted the reductions, considering motives such as protection from forced labor and the perception that the priests had interesting spiritual and material powers.Footnote 6

From early on, the Jesuits confronted the hostile proximity of the Portuguese from São Paulo (the Paulistas). Prior to their arrival, the Paulistas were already capturing and enslaving native peoples in the interior regions of Brazil but soon expanded their operations into Paraguay. Their first major expedition there took place between 1602 and 1604, when they captured 700 natives from Spanish encomiendas. Initially, the bandeirantes (as Paulista slave raiders were known) were more interested in enslaving women and children. John Monteiro examined a list of 628 Guaraní captives from the year 1615. Seventy percent were women and children, which, as explained by Barbara Ganson, “reflects the sexual division of labor in agriculture in which women were predominant in the planting and harvesting of crops.”Footnote 7 Scholars disagree on how many natives the bandeirantes enslaved in Guairá and Paraguay in the first half of the seventeenth century, but whether the number was 100,000 or 300,000, it is certain that large-scale slave trading had a tremendous impact on the native societies of the South Atlantic.

Most of the enslaved natives were employed in São Paulo, but a not insignificant number may have been sent to other parts of Brazil, such as Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, and Bahia.Footnote 8 Some bandeiras were led by Portuguese captains and had the backing of the governor of São Paulo; others, organized by independent slaveholders, dispensed with this veneer of legitimacy. The Paulistas were guided through the interior of Brazil by Tupi allies, enemies of the Guaraní evangelized by the Jesuits or in service to Spanish encomenderos. Many Paulistas had indigenous heritage, and by associating themselves with native women, they obtained the status and power of native chiefs.Footnote 9

Initially, the bandeiras undermined encomenderos’ activities more than those of the priests. In 1619, the city of Asunción complained that the Portuguese had captured as many as 7,000 natives and sold them as slaves in Brazil.Footnote 10 This scenario changed in the following decades: natives concentrated in missions were easier to capture, and some encomenderos saw advantages in allying with the Paulistas to destabilize the Jesuit program that limited their access to Guaraní labor.Footnote 11

The Jesuits wasted little time in protesting against the Paulistas’ abuses in Madrid. At that time, Portuguese domains were part of the Spanish empire under the Iberian Union (1580–1640). In September 1627, provincial Durán Mastrilli wrote to procurator Francisco Crespo in Buenos Aires, warning of the danger posed by the bandeirantes’ proximity to the province of Guairá: “The greatest hardship suffered here,” Mastrilli wrote, “is the insolence of many Portuguese from the village of San Pablo . . . , who come every year to enslave the Indians of these nations, taking them to Brazil, selling them as slaves and using them as such.” Mastrilli pleaded for intercession from the king of Spain, the Count-Duke of Olivares (chief minister to Philip IV from 1621 to 1643), and the Council of Portugal, and presented the depopulation of the village of São Paulo as the only solution for preventing “these tyrannies and cruelties.”Footnote 12 Crespo presented a petition to Philip IV with the same content as Mastrilli's letter, and a royal cédula of September 12, 1628 transmitted similar news to the governor of Río de la Plata. Philip IV's actions at that moment, however, were limited to recommending that authorities “[try] by all possible means to have the offenders punished in an exemplary manner.”Footnote 13

Jesuit priest Antonio Ruiz de Montoya witnessed Portuguese incursions firsthand as a missionary in Guairá and later served as the Jesuit procurator in Madrid. In this article, I focus on his activities as a petitioner for his order in the 1630s and 1640s. Ruiz de Montoya was born in Lima in 1585, the only son of Captain Cristóbal Ruiz de Montoya, a native of Seville, and Ana de Vargas, born in Lima. Orphaned at the age of nine, he decided after some hesitation to study philosophy and theology at the colegio of Santiago de Chile.

Following his 1611 ordination as a priest, Ruiz de Montoya was promptly sent to the Jesuit mission of Loreto in the Guairá. There, he became a central figure in the organization and defense of the Guairá missions against Paulista raids. In 1631, he oversaw the transfer of more than 12,000 Guaraní to new settlements along the Paraná River. In 1636-37 he served as superior of all the Guaraní missions. Also in 1637, he was appointed procurator before the court of Madrid to request remedy against the attacks on the missions. Most scholars have emphasized Ruiz de Montoya's lobbying efforts to create Guaraní militias and obtain tax advantages for Jesuit reductions. This essay focuses on Ruiz de Montoya's efforts (so far less studied) to halt Portuguese slave activities by bringing about a major administrative intervention by the Spanish crown in Portuguese domains during the late period of the Iberian Union.Footnote 14

In the Spanish empire, procurators were agents who represented the interests of individuals or groups in courts or other institutions. Religious orders usually chose procurators to lobby for the interests of each overseas province before the Council of the Indies (the king's main advisory body for the administration of the Indies) and other royal and ecclesiastical authorities.Footnote 15 In fact, by the early seventeenth century, subjects of the Spanish monarchy recognized the importance of having a procurator in Madrid to push the court to favor their petitions. Writing from Cochabamba in 1633, Father Antonio Luis Lopes de Herrera lamented that Peruvian vassals “barely got the crumbs that fell from the king's abundant table” because of their distance from the metropole. The religious were particularly disadvantaged and received very few concessions, with the exception of those who had someone at court to look after their interests.Footnote 16

Jesuit provincial congregations chose their procurators every six years. The procurators traveled to Madrid and Rome to petition for benefits for their province, before both the Council of the Indies and the superior general of the Society of Jesus. Scholars have documented the efforts of these procurators to obtain not only religious and economic privileges for their provinces, but also all sorts of material goods, such as liturgical objects, books, and other products.Footnote 17 These studies have increased our understanding of the role of the Jesuit procurators as lobbyists for material and human aid for the missions. However, little is known about their other political activities in Madrid, or about the other more ambitious projects they presented to the crown with ideas for administrative imperial reform.

Portuguese slave raids in Paraguay and in the interior and south of Brazil had a profound impact on the region's native societies, on relations between the Portuguese, Spanish, and Jesuits, and on the territorial conformation of the Iberian empires in the South Atlantic.Footnote 18 Despite the enormous literature available regarding the interactions between Guaraní, Jesuits, bandeirantes, and other Iberian agents in the South Atlantic in the early seventeenth century, the extent to which political communication between the Jesuits and Madrid interfered with those conflicts has been little studied.

In this article, I suggest that Ruiz de Montoya's activities as procurator in Madrid in the 1630s and 1640s went far beyond the usual work of the procurators for the religious orders. In their petitions, the procurators usually presented a summary of the difficulties and promises of the region they represented and concluded by asking for financial aid from the crown and for more priests. Instead, Ruiz de Montoya's papers called for a profound reform in the administrative structure of the empire in the South Atlantic. In doing so, Ruiz de Montoya seems to have joined a select group of arbitristas (projectors) who were able to convince the crown to adopt the reforms they proposed, something that scholars have so far failed to recognize. In the Spanish monarchy, people of any social status could send arbitrios (projects) to the king's councils to propose reforms and governmental interventions, to solve concrete problems in their local communities, or to address concerns in the broader spheres of the empire.Footnote 19 Numerous studies have shown that this form of political communication was widespread in both the seventeenth-century Spanish and Portuguese empires.Footnote 20 Although the crown rejected many of the proposals, it encouraged their production because they were an important source of information.Footnote 21 Arbitristas could become the laughingstock of the literati of the time.Footnote 22 However, Madrid considered some of the proposed reforms to be of plausible benefit and applied them, even if they entailed significant changes to imperial governance.Footnote 23

Ruiz de Montoya's proposals fall into this category. Madrid decided to implement them, even though they represented far-reaching changes in the governance of its South Atlantic empire. In this article, I argue that collaboration between Ruiz de Montoya and Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça, a Portuguese secular priest, was crucial to Madrid's approval of these reforms. Mendonça, after mission work among natives in Peruvian mining regions, worked as a prelate in Rio de Janeiro and witnessed the havoc wreaked by the bandeirantes. Mendonça was an active petitioner to the Council of the Indies, and it is interesting to note that Ruiz de Montoya's proposals were very similar to his.Footnote 24 Among these proposals were the creation of a bishopric and an Inquisition tribunal in Rio de Janeiro; the designation of bandeira activity as a crime falling under inquisitorial jurisdiction; and the enforcement of existing laws that prohibited indigenous slavery.

It is important to mention that Madrid approved these reforms while Portugal was united with Spain in the Iberian Union. In practice, the reforms Mendonça and Ruiz de Montoya proposed signified a break with the premises of the 1581 Cortes de Tomar, according to which Spain would respect Portuguese law and each crown's domains would be administered with total autonomy in relation to each other.Footnote 25 Portugal's independence in 1640 probably eclipsed historians’ attention to the magnitude of the reforms Madrid was about to implement. I argue here that they were the materialization of a political vision for the jurisdictional unification of the Iberian empires in the South Atlantic.

Scholars have written extensively about Jesuit procurators’ lobbying activities, but most of these works have focused on their efforts to get financial aid to the missions. The Jesuits’ petitions containing imperial reform projects, which showed their participation in the arbitrista tradition of the Spanish empire, are still little known. Recent studies have shown that the Spanish empire was less hierarchical than assumed, but we still know little about how the Jesuits fit into this context, in which diverse actors shaped crown policy through petitions.Footnote 26 This article shows a little-known facet of the Jesuits: their actions as proponents of reforms that would have had a major impact on the Spanish empire by leading to a de facto incorporation of the Portuguese domains into Madrid's imperial guidelines.

This article is divided into three parts. The first deals with the reports of Ruiz de Montoya and his fellow Jesuits to the crown regarding Paulista slavers’ incursions against Jesuit missions. The second part focuses on the Jesuits’ representation of the Portuguese of Brazil in their writings and the origins of the idea of setting up an Inquisition tribunal in Rio de Janeiro. I further examine how the collaboration between Lourenço de Mendonça and Ruiz de Montoya contributed to Madrid's positive evaluation of their projects. The article concludes with an epilogue that discusses Ruiz de Montoya's activities after 1640 and an evaluation of the impact of his writings on the political communication of the early seventeenth-century Spanish empire.

Bandeiras and Indigenous Slavery

Ruiz de Montoya arrived at the missions of the Paranapanema River valley in 1612, joining two Italian Jesuits, José Cataldini and Simón Maceta, who had arrived there two years prior.Footnote 27 In 1617, the mission of Loreto had 350 married couples and the mission of San Ignacio had 425; some 1,200 boys attended mission schools.Footnote 28 Appointed superior of the mission of Guairá in 1622, Ruiz de Montoya described the prosperity of these reductions and warned of the increasingly palpable threat of incursions by Portuguese and their Tupi allies. In his 1628 annual letter, he wrote that the Paulistas captured only groups that were not yet reduced and warned that the bandeirantes threatened to kill anyone who tried to stop them from taking captives to São Paulo.Footnote 29

In his book Conquista espiritual, published in 1639, Ruiz de Montoya detailed the bandeirantes’ activities.Footnote 30 He described how the Paulistas instigated conflicts among native groups and performed “rescues” of captives by bartering them with tools provided by creditors living along the Brazilian coast. This mode of exchange revealed the existence of a network of people who were involved in financing the expeditions and participated in the distribution of indigenous slaves. Ruiz de Montoya learned from some Tupi about the “pombeiros” and their central role in the slave trade. This term was used in Congo and Angola to refer to the men, often of mixed African and European descent, who obtained slaves in the interior for Portuguese traders on the coast.

In central-southern Brazil, pombeiros were indigenous slaves who specialized in enslaving other natives from the independent villages of the interior. They divided the sertão (backlands) into regions among themselves, and each had his own trading post where he kept knives, axes, machetes, and other tools, as well as clothes, hats, beads, and other European items. By offering these products in exchange for captives, pombeiros encouraged natives to wage war against other native groups to obtain captives and even to sell their own relatives. With the pombeiros, Paulistas began to depend on their own slaves to bring people from the sertão, rather than on independent intermediaries; the result was to boost the slave trade to new heights.Footnote 31

The Paulistas used several pretexts for their actions in Guairá. The bandeira of 1628–29 was one of the most important. Led by Antonio Raposo Tavares and composed of 900 Portuguese and 2,200 natives, the expedition operated under the pretext that the residents of Villa Rica of Paraguay were invading Portuguese territory. It was a dubious claim, since the very borders between the domains of Portugal and Spain were uncertain during the Iberian Union.Footnote 32 Raposo Tavares erected a palisade in the vicinity of the mission of Encarnación. He told the Jesuits he was capturing autonomous natives, but quickly began capturing natives from the reduction. Ruiz de Montoya and other Jesuits pressured the Paulistas to free the captives. After four months of tension, the Paulistas invaded the mission of Santo Antonio, destroyed its buildings, and enslaved more than a thousand natives, killing any who resisted. The Jesuits learned that the Paulistas later sold them as slaves in São Paulo.Footnote 33

Luiz Felipe de Alencastro has estimated that between 1627 and 1640, the Portuguese captured 100,000 natives from the missions of Guairá, Tape, and Itatín, or 7,143 per year. He also assumes that the number was higher than the number of enslaved Africans introduced to Dutch and Portuguese Brazil during the same period.Footnote 34 It is possible that the number of Guaraní captives was even higher.Footnote 35 The governor of Buenos Aires estimated that the bandeirantes took 60,000 natives from Spanish missions to Portuguese domains between 1628 and 1630.Footnote 36 Jesuits Justo Mansilla and Simón Maceta witnessed the capture of 20,000 natives by the 1628–29 bandeira as they tracked the Paulista enslavers’ return to Brazil. These Jesuits estimated the number of natives captured between 1628 and 1631 at 200,000.Footnote 37 The author of a memorial delivered to Viceroy Chinchón estimated the natives taken before 1632 at 50,000.Footnote 38 By 1634, the bandeiras had captured more than 10,000 souls from the newer reductions.Footnote 39 Finally, the Spanish crown estimated that, between 1614 and 1639, the bandeirantes had taken 300,000 indigenous captives.Footnote 40

While the death toll of these natives after their arrival in Brazil was certainly high, exacerbated by the terrible working conditions, it should be noted that many died in the “middle passage.” As described by Fernanda Sposito, the natives suffered all sorts of violence on the journey to São Paulo, which could last more than a month. Captives were frequently tortured and those who escaped were arrested and killed to terrorize the others. To avoid slowing down the march, slavers abandoned the elderly, young children, and the disabled along the way.Footnote 41 When Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça traveled through the region as a visitor in the mid 1620s, he found that the bandeira of 1625 had captured 7,000 natives; only 1,000 arrived alive in São Paulo.Footnote 42

The bandeira of 1628–29 revealed the vulnerability of the Jesuits’ missions in the Guairá. On October 10, 1629, the Jesuits sent a report to the king detailing the bandeirantes’ hostilities. Mansilla and Maceta drafted this paper in the city of Salvador da Bahia.Footnote 43 In March of that year, Raposo Tavares and his companions carried out destructive attacks on the missions of Jesús María and San Miguel, after having already destroyed two others. These attacks resulted in the capture of thousands of people. In response, the Jesuits assigned Fathers Mansilla and Maceta to accompany the Portuguese back to Brazil. Their purpose was to express their objections to the Brazilian authorities, aiming to put an end to such expeditions and ensure the return of the native population. However, upon their arrival in Brazil, they were disheartened to discover that the authorities either supported these expeditions or showed indifference towards them. In São Paulo, local officials prevented Mansilla and Maceta from staying at the colegio of the Society of Jesus.Footnote 44

The two men then decided to go to Rio de Janeiro. Explaining the situation to the ouvidor (magistrate), Maceta noted that he did not dare to question the customs of the Paulistas, “for he knew the rebelliousness of those people.” The case was transferred to the general government in Bahia.Footnote 45 Some witnesses gave testimony in Salvador in September 1629, and governor-general Diogo Luís de Oliveira appeared to support the Spanish Jesuits’ cause.Footnote 46 He ordered the arrest of the criminals, the seizure of their goods, and the release of the indigenous slaves. If the slavers ran away, “their effigies should be hung,” to serve as an example.Footnote 47

Mansilla and Maceta returned to São Paulo in July 1630, accompanied by Francisco da Costa Barros, a royal official and notary from Rio de Janeiro, who carried Oliveira's decree against indigenous slavery.Footnote 48 Apparently, even the Jesuits themselves doubted the enforceability of the decree. They observed that the governor-general received questionable “gifts” from the Paulistas, suggesting a complicit relationship between them. And their doubts were well-founded. The Paulistas immediately rebelled against Barros’ presence. They not only threatened him with death but also expelled him from the town.Footnote 49 Realizing their own vulnerability, Mansilla and Maceta took the earliest opportunity to retreat and returned to the Loreto de Guairá mission by the end of the same month.Footnote 50 Father Maceta, drawing a comparison to the rebelliousness of a contemporary French city, described São Paulo as the “La Rochelle” of Brazil.Footnote 51

Informed of Mansilla and Maceta's failures to influence Brazilian authorities and fearful of a new bandeira, in 1631, Ruiz de Montoya organized the evacuation of approximately 12,000 indigenous people from Guairá. They traveled by river in 700 canoes and then overland approximately 520 miles (or 836 kilometers) to settle in the current territory of Misiones (Argentina). Recognizing the Jesuits’ lack of proper authorization from the Audiencia of Charcas for this relocation, Ruiz de Montoya documented that the Spanish residents of Ciudad Real erected a palisade near the Paraná waterfalls “to impede our passage” and “apprehend the people.”Footnote 52 Since the Spanish were few in number, the Jesuits and their natives forced their way through the palisade without being seriously harassed.Footnote 53 However, the exodus was a tragic experience overall. In one single epidemic, 1,500 people died.Footnote 54 According to Barbara Ganson, just one third of the natives made it through this forced migration; the rest died of epidemics or hunger, or were captured by the Portuguese.Footnote 55

While indigenous slave labor remained crucial to São Paulo's economy, Jesuits and other observers also noted sales of captives from the Spanish missions in other captaincies. Upon arriving in Bahia, Mansilla and Maceta accompanied ouvidor-geral Miguel Cisne de Faria as he conducted interrogations of witnesses regarding the trading of indigenous slaves along the Brazilian coastline. The depositions took place in Salvador on September 17, 1629, and revealed a common practice facilitated by the smooth coastal navigation between Santos, Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, and Bahia. The most common vessel was the patache, an old sailing ship with a bowsprit and two masts. One man said he had witnessed the sale of 45 adult natives in Espírito Santo and two children in Bahia. Slavers also sold a group with 25 natives, probably from among those captured by Raposo Tavares in Rio de Janeiro and Bahia.Footnote 56 The Portuguese sold the natives in a public square and called them slaves. Moreover, they separated children from their parents and wives from their husbands, forcing them to remarry in Brazil.Footnote 57

In the following years, other observers witnessed the continuing sale of enslaved Guaraní along the coast of Brazil. In 1637, Buenos Aires governor Pedro Esteban Dávila wrote that when he arrived in Rio de Janeiro, “the Indians brought by the residents of San Pablo were sold before his eyes in that city, as if they were slaves.”Footnote 58 In 1638, when Ruiz Montoya was in Rio de Janeiro waiting for the ship that would take him to Spain, he saw Paulistas selling Guaraní from the missions in exchange for gunpowder and weapons.Footnote 59 Writing in 1636, Spanish traveler Manuel Juan de Morales estimated that there were 40,000 enslaved natives in São Paulo. The Portuguese masters treated their slaves harshly, subjecting them to exhausting workdays and providing only meager food, mainly reduced to corn.Footnote 60

The Jesuits were consistent in describing the natives captured by the bandeirantes as slave laborers in colonial ventures on the coast of Brazil.Footnote 61 In one of his 1639 memoriales, procurator Ruiz de Montoya wrote that he was certain most of the natives captured in Paraguay were in São Paulo, but that the slave traders had also sold a significant number in Rio de Janeiro and some even as far away as Lisbon.Footnote 62 The Council of the Indies had no doubt that the Portuguese enslaved natives: “They enter the Indian reductions and take them captive and carry them violently to Brazil, and sell them as slaves, and occupy them in very laborious servitude, as in the sugar mills and on their farms.”Footnote 63

Another constant in the Jesuits’ memoriales was the attempt to define who was responsible for the damages to the missions. The Jesuits believed that Spanish settlers in Paraguay were accomplices of the Portuguese. This was not surprising, since the Spanish themselves exploited natives in the yerba maté plantations of the Paraná River valley. In 1630, the caciques of San Ignacio sent a petition to the Audiencia of Charcas (written in Guaraní and translated by the Jesuits) in which they criticized a recent royal provision of that court that allowed natives to be employed in mita for two months and to work on the Maracayú yerba maté plantations, although “only if they wanted to go.” Paraguayans used the term mita to describe the work shifts that natives living in pueblos did for their encomenderos. This modality was defined as encomienda mitaria, in contrast to the originaria, in which natives lived permanently with their employers.Footnote 64

The caciques referred to the abuses natives suffered as mitarios in the extraction of yerba. They also noted that the Spanish could interpret the decree in such a way as to continue to exploit natives: “And so we ask you for the love of God that you let our King and Lord know what we say and ask so that he will order us not to go to Maracayú even if we want to, because if [the king] says we could go if we want to, the Spaniards will harass us and take us there not only with this precaution but also against our will.”Footnote 65

Jesuit provincial Francisco Vázquez Truxillo understood that the Spaniards of Villa Rica had made some kind of agreement with the Paulistas, since they usually did nothing when they learned of the capture of natives.Footnote 66 José Vilardaga has examined one of the cases in question. He showed that in 1631, Francisco Benítez, a resident of the city of Villa Rica, was accused of using his position as commander of the militia defending that region to facilitate the Paulista slave raids.Footnote 67 Ruiz de Montoya noted that the Spanish militias sent to stop the Portuguese joined them in robbing and capturing natives.Footnote 68 In fact, according to Vázquez Truxillo, a good part of the residents of Villa Rica were of Portuguese origin.Footnote 69 Spanish officials also had information that the Paulistas were marrying in the Spanish cities that neighbored the regions they raided in search of slaves.Footnote 70 In 1633, the Jesuits accused Spanish lieutenant Lorenzo de Villalba of allying with the Portuguese, from whom he received indigenous slaves for his compliance. From his house near the Paraná River, Villalba dispatched a contingent of 22 Spanish soldiers and indigenous allies to conduct a survey of the frontier. However, upon their return, they brought back over 300 native captives, the majority of whom hailed from Jesuit reductions.Footnote 71 Villalba was probably trying to incorporate these captives as encomienda originaria, a practice commonly observed in Paraguay.Footnote 72

In 1632, several witnesses denounced Diego de Urrego, a resident of Xerez, for having assisted the Paulistas in an incursion to Itatín. He allegedly guided the bandeirantes to the village of a cacique named Pazagu and provided logistical support for the transport of up to 2,000 enslaved natives. Apparently, the Paulistas offered him asylum in São Paulo.Footnote 73 These episodes reveal that for many Spaniards, the Paulistas, rather than a threat, could be key actors in destabilizing the Jesuit missionary program, which limited Spaniards’ access to Guaraní labor.

The Jesuits were particularly incisive in denouncing the governor of Paraguay, Luis de Céspedes Xería, for his complicity with the Paulista expeditions. Céspedes Xería had served the Spanish crown in the wars in Chile and was appointed to the government of Paraguay in 1625. He entered the province through Brazilian lands, passing through Salvador, Rio de Janeiro (where he married the niece of governor Martim de Sá, who was the son of Salvador Correia de Sá), and São Paulo. The Sá family had great influence in Rio de Janeiro and good connections in Paraguay, the Río de la Plata, and Tucumán. Salvador Correia de Sá was married to Catalina de Ugarte y Velasco, daughter of an important landowner and niece of Luis de Velasco, the viceroy of Peru.Footnote 74

In São Paulo, Céspedes Xería did not take any action against the bandeiras; on the contrary, he showed the Portuguese as much sympathy as possible. However, his relations with the inhabitants of São Paulo were not so friendly as the Jesuits presumed. In a 1628 letter to Philip IV, Céspedes Xería denounced the Paulistas who had entered Paraguay and captured numerous natives from the Jesuit missions. He urged the crown to remain vigilant regarding these bandeiras. Céspedes's relationship with the São Paulo câmara was particularly tense: local officials demanded that he present a royal permit before they would allow his entourage to pass through São Paulo, causing him to hurry his departure. He later referred to the Paulistas as “people who committed the greatest evils, treacheries, and villainies.”Footnote 75

Despite some apparent sympathies, the Jesuits built a strong case against Céspedes in their memoriales. Arriving in the Spanish villages located on the border of Paraguay, the new governor was well received by the local elite and heard complaints against the arbitrariness of the Jesuits for monopolizing indigenous laborers and not favoring the encomenderos and their enterprises. In Villa Rica, Céspedes received a petition from the procurator of that city, Francisco de Villalba, to authorize the natives of the reductions to “serve and pay mita to their encomenderos.”Footnote 76

Céspedes Xería seemed to share an antipathy toward the Jesuits with the frontier Spaniards. In November 1628, he appointed Felipe Romero visitador of the reductions and instructed him to identify all the indigenous refugees in the missions and return them either to the encomenderos or to the Portuguese. Romero was also to encourage the natives to disobey the Jesuits if they received orders “contrary to the king's service.”Footnote 77 Not surprisingly, the encomenderos of Santiago de Xerez and Villa Rica praised Céspedes's government, while the Jesuits immediately opposed him.Footnote 78 Ruiz de Montoya, for example, refused to accompany him in visiting some reductions.Footnote 79

In their memoriales, the Jesuits alleged that the new governor had come to Paraguay accompanied by Paulista slavers, who resumed their raids after returning to São Paulo. The priests also insisted that Céspedes harassed the natives by putting them to work on the yerba plantations, and that he encouraged disrespect toward the priests. Since Céspedes had married in Rio de Janeiro and had received a sugar mill in that city as a dowry, they suggested that the governor supported the slavers in order to secure a supply of slaves for his own plantation. It is worth noting that Céspedes traveled ahead of his wife, hoping perhaps to maintain good relations with the Paulistas to ensure her safe passage to Paraguay.Footnote 80 Father Francisco Crespo's 1631 memorial asserted that the governor had authorized the Paulistas to capture 2,000 natives on his behalf, to be delivered to his mill, which would be his bribe for allowing the bandeiras to capture natives in Guairá.Footnote 81

While the Jesuits accused Céspedes of complicity with the Paulistas, the governor accused the Jesuits of being the real troublemakers in the region. On June 23, 1629, Céspedes Xería sent an extensive report to the king in which he gave an account of what he had seen in the Guairá missions. According to Céspedes, the Jesuits were insubordinate to royal authority, refusing to help the governor with material and human resources during his visit to the missions. In addition, he reported that the priests illegally supplied natives with firearms, kept Tupi fugitives from Brazil in the missions instead of turning them over to civil authorities, and hindered the encomenderos’ access to native laborers.Footnote 82

In this war of information, the Jesuits seem to have prevailed. In 1631, Father Francisco Díaz Taño, procurator of Paraguay, sent a memorial to the Audiencia of Charcas in which he accused the governor of “omission and negligence” for failing to notify the Audiencia “of so many robberies, deaths and captivities and destruction of villages as occurred from the year 1629 to 1631.”Footnote 83 Ruiz de Montoya was one of the most insistent on Governor Céspedes's responsibility. In his 1631 statement about the attacks on the Guairá, the Jesuit specified two particularly explosive reasons: first, he reported that Céspedes had suggested to him that the Jesuits abandon their missions, as the Paulistas would soon destroy them. Moreover, Ruiz de Montoya relied on testimonies by Jesuits Simón Maceta and Justo Mansilla, stating that they had seen natives from Paraguay laboring in Céspedes's sugar mill in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 84 Probably as a result of these denunciations, Céspedes Xería was taken to Charcas in 1631 and imprisoned there for a time. But by 1635, he was back in Buenos Aires. He spent some time in Paraguay and died in Rio de Janeiro in 1667.Footnote 85

The Inquisition and Indigenous Freedom

Ruiz de Montoya arrived in Madrid on September 22, 1638, to serve as procurator for the Jesuits in Paraguay. Soon after, probably in that same year, he submitted two memoriales to the Council of the Indies. In the first, he offered a brief account of the Portuguese invasions and presented Raposo Tavares as the chief person responsible.Footnote 86 In the second, he offered a set of wide-reaching administrative reforms for the Spanish empire in the South Atlantic. He insisted on the need to protect natives from slavery; advocated considering the enslaving of natives as a crime under inquisitorial jurisdiction; and proposed the creation of a bishopric and an Inquisition tribunal in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 87 What was the origin of such proposals? What were their political and legal foundations? What did the Council of the Indies decide in this regard?

Ruiz de Montoya was not the first to think of the Inquisition as a solution to the problems of the viceroyalty of Peru. For example, in his 1614 memorial, Miguel Ruiz de Bustillo advocated appointing an inquisitor for each bishopric to avoid the disturbances that were generally caused by newcomers and foreigners, who were increasingly numerous in the kingdom. The inquisitors’ salaries would be paid for with funds from the sale of posts.Footnote 88

An anonymous proposal sent to Madrid by Viceroy Chinchón in 1632 defined four means for solutions to counter the Portuguese invasions. The first suggested granting freedom to the Paraguayan natives in Brazil. The second proposed Philip IV's purchase of São Paulo from Lope de Souza's descendants, allowing direct appointment of governors backed by military support. The third called for moving Paraguay's capital to Villa Rica to protect it from Portuguese influence. Lastly, the fourth proposal recommended the destruction of São Paulo for its crimes. Although the specific order of implementation is unclear, it appears evident that the destruction of the city should precede the arrival of the new Spanish governor and the subsequent reorganization.Footnote 89

Ruiz de Montoya's 1638 memoriales differed from previous ones, however, in their blunt suggestion that the residents of São Paulo were under the influence of Protestantism or Judaism, which would make their actions suitable for inquisitorial jurisdiction. In the first memorial of 1638, he stated that the bandeirantes made Christianity odious to the natives, and that they were close to the Dutch either through Judaism or heresy, thus endangering all of the viceroyalty of Peru.Footnote 90

The second memorial contained a more thoroughly developed argument for the Inquisition as a remedy against indigenous slavery. Ruiz de Montoya began by defending the application of a law of September 10, 1611, which in his understanding guaranteed indigenous freedom. In reality, this 1611 law allowed slavery in cases of “just war” and represented a step backward from another law from 1609.Footnote 91 Ruiz de Montoya's second memorial relied on two Jesuit theologians, Fernando Rebello (1546–1608) and Luis de Molina (1535–1600), Franciscan theologian Manuel Rodrigues (1545–1619), and Spanish Jurist Juan de Solórzano Pereira (1575–1655). According to Ruiz de Montoya, the bandeirantes’ activities not only hindered the promulgation of the Gospel, but also caused the natives to lose their faith. The slavers destroyed temples and mocked religious images. They inculcated heresies and sins in the natives, such as polygamy and salvation by faith and not by works. Even more serious, Ruiz de Montoya presented evidence that the Portuguese manifested Jewish customs. The Paulistas, for example, did not obey Catholic food taboos and gave the indigenous slaves names from the Old Testament, such as Adam, Eve, Habakkuk (Abacú), Daniel, and others. Ruiz de Montoya considered it well known that there were Judaizing natives in Rio de Janeiro. A bishopric and an Inquisition tribunal in Rio de Janeiro would solve the problem, even helping to curb the corruption of officials who were the bandeirantes’ accomplices.Footnote 92

The Jesuits relied on the widely held belief that many Portuguese had Jewish origins to argue that the bandeirantes were Judaizers. Reporting to the king in 1620 regarding the situation in his jurisdiction, the archbishop of Charcas referred to the Portuguese entering Peru in the following terms:

Many foreigners pass into this kingdom . . . and many more Portuguese, who are not loyal to the crown of Castile and it is convenient to expel them from this kingdom and province. First, because of the danger of [their] being spies, and joining our enemies, who every year disturb us and cause some rebellion among restless people. Second, because they enjoy this kingdom and defraud it of a great part of silver, since they do not come for anything else, and as greedy people they become dealers in any kind of trade when they enter this kingdom.Footnote 93

In Spanish America, the terms “Portuguese” and “Jew” were considered synonymous.Footnote 94 It is interesting to note that the archbishop of Charcas's distrust of the Portuguese did not focus on this group's supposed “inferiority,” but on the assumption that they were more efficient than the resident Spaniards in trading and obtaining precious metal. Scholars who have compared so-called “middleman minorities” in various societies have found that such a stereotype was not uncommon.Footnote 95 The Portuguese were the predominant foreign group in the early sixteenth-century Spanish empire, comprising, according to Nathan Wachtel, more than 15 percent of the residents in certain cities, including Buenos Aires, Potosí and Veracruz.Footnote 96 By the early 1620s, however, hostilities between Spain and the Netherlands and the correspondence between Portuguese conversos and their relatives in the Netherlands, France, and Italy had led Spanish authorities, and particularly the Inquisition, to be increasingly suspicious of the Portuguese.Footnote 97

Allegations that Jews were flooding Peru had long been in circulation. In 1623, Philip IV ordered the Council of the Indies to look at reports from some recent discussions in the Council of the Inquisition about “the entrance of those of the Hebrew nation into Peru” and the means that the General Inquisitor had proposed to prevent this.Footnote 98 The Council of the Inquisition's consultations had been prompted by a memorial written by Manuel de Frías about the entry of Portuguese through Buenos Aires. In his memorial, Frías mentioned that these “Jews” traded enslaved Africans and European goods with their contacts and friends in Peru. Frías understood that they could cooperate with enemy powers and favor the loss of territories. As a solution, he proposed that at least one inquisitor reside permanently in Buenos Aires.Footnote 99 Identifying the foreigners entering through Buenos Aires as “New Christians from the Hebrew nation of the kingdoms of Portugal,” the general inquisitor expressed his full agreement with Frías's proposal and even suggested creating an Inquisition tribunal in that city.Footnote 100 The Council of the Inquisition's 1621 consultation also identified the Portuguese as “of the nation,” mentioning stereotypes such as doctrinal errors, avarice, the usurpation of royal revenues, and alliances with foreign powers. They also warned against the risk that these merchants might be sending riches to “strange kingdoms and infected provinces.”Footnote 101

Writing in 1623, the Council of the Inquisition alerted the monarch to the urgency of the situation, raising several issues: the fear that Jews, whom they referred to as “infectious people” (gente infecta), would “contaminate” the Spanish residents; the distance between Buenos Aires to Lima, which made the entry of Portuguese a problem that could be solved only if a commissioner of the Holy Office resided in the Río de la Plata; and the urgency of that business, as it was reported that many of those entering were fugitives from Inquisitor Marcos Teixeira's 1618–21 visitation in Bahia.Footnote 102 According to Francisco de Trexo, commissioner of the Holy Office of Peru in the port of Buenos Aires, eight ships bearing Portuguese conversos fleeing Brazil had landed in Buenos Aires in 1618–19.Footnote 103

In 1622, Francisco de Trexo wrote to the Council of the Inquisition, stating that the Portuguese, in addition to being slave traders and bandeirantes, were probably Jews because of their irreverent treatment of the crucifix and other abuses.Footnote 104 This circulation of denunciations, proposals, and assessments illustrates that, at the time Ruiz de Montoya was writing, the idea that many Portuguese were Judaizers was widespread among Spanish royal officials, from the local level to the higher councils. Ruiz de Montoya had maintained that the bandeirantes were Jews since at least 1631. That year, he included his account as superior of the Guairá missions in a collection of testimonies made by Jesuits working there and collected by the provincial Francisco Vázquez Truxillo to persuade the Spanish crown to do something about the Paulistas. He noted that: “The cruelties and disrespect of the Portuguese toward the Indians, the priests, and sacred things are more typical of Jews and heretics (as many of them I understand are . . .) than of bad Christians.” He also reported that when a priest asked why the bandeirantes were waging war against the natives, Raposo Tavares replied that it was “because of the permission that God gave them in the books of Moses.”

The Jesuit was naturally writing to an audience familiar with the Pentateuch verses that describe how the Israelites acquired slaves from other groups either by purchase (Exod. 12:44) or capture in war (Deut. 20:14), and that such slaves were held permanently (Lev. 25:44-46). As Jews, continued Ruiz de Montoya, the bandeirantes did not work on Saturdays, “keeping it as a feast day,” and despised religious images, placing images of the Virgin Mary on the soles of their shoes.Footnote 105 An anonymous memorial sent by Viceroy Chinchón insisted that it was common for the Portuguese to tell natives that Catholic law was false and that Jesus Christ was not God.Footnote 106

However, Jesuits’ accusations equating the Paulistas with Jews were not consistent, since they also labeled them as Protestants. The Jesuits insisted that the bandeirantes believed that everyone could be saved by faith, not by works. Simón Maceta reported the following: “These bad men must be heretics or Jews, or both, for one of them said ‘in spite of God I must be saved even if I do not do good works, because it is enough that I am a Christian.’”Footnote 107 In one memorial, Ruiz de Montoya affirmed that it was common for the Portuguese “to say that works are not necessary to be saved, but that it is enough for them to be baptized, and that even if it does not please God they will be saved.”Footnote 108 Later, Ruiz de Montoya described the Paulistas as iconoclasts: “burning and desecrating the temples, dragging the priestly garments, spilling the holy oils.”Footnote 109 During the siege of the Jesús María reduction, directed by Maceta, the bandeirantes desecrated and destroyed the interior of the church, killed three pigs, and ate them for Lent.Footnote 110

In the Jesuits’ descriptions of the incursions of the 1620s and 1630s, they endeavored to link the Paulistas, in a diffuse way, to Protestant heresy and the imminent possibility of a break in monarchical loyalty. Jesuit Diego de Boroa, who was in the reduction of Jesús María in Tape when the Paulistas attacked it, claimed that the Paulistas were loyal not to Philip IV but to the Count of Monsanto, the current proprietor of the captaincy of São Vicente. As proof of their religious infidelity, he pointed out that the bandeirantes, in addition to indiscriminately killing indigenous men, women and children, had desecrated and burned the churches, religious images, and holy oils; torn the baptismal book to pieces; and stolen precious liturgical objects, “showing themselves crueler than beasts and more inhuman than Arabs (alarbes), Calvinist heretics, or Huguenots.”Footnote 111

Diego de Boroa was not the only one to doubt the Paulistas’ loyalty and to assume that they were, in fact, following the party of the Count of Monsanto. In 1636, Manuel João Branco, a resident of São Paulo who, in historian Jaime Cortesão's opinion, was nothing more than a Spanish spy, authored a memorial to the king providing a remedy for those ills. Branco suggested that it was necessary to evict the Count of Monsanto from his possession of the captaincy of São Vicente and submit it to the direct control of the Spanish crown.Footnote 112

Ruiz de Montoya's description was deliberately ambiguous; he avoided labeling the Paulistas as Jews so as to have some margin with which to identify them as sympathetic to the Dutch enemy and thus disloyal to the monarchy. In a memorial, the Jesuit even said that the Paulistas contradicted the doctrine taught by the priests and considered it legitimate to have more than one wife.Footnote 113 By portraying the Paulistas as disdainful of religious images and engaging in forbidden meals during Lent, Ruiz de Montoya established a connection between them and the Protestants. However, the Jesuit's suggestion of a “conspiracy” involving the Paulistas, the Dutch, and the Jews carries significant weight. This alleged conspiracy aimed to bring Dom Antonio's son from Holland to Brazil, intending to establish him as a rival king to challenge Spain. Dom Antonio, prior of Crato (1531–95), was a claimant to the throne of Portugal who was defeated by Philip II in 1580. Although Ruiz de Montoya did not disclose how he came across these ideas, he dismissed their importance while also hinting at the possibility of their origin from Jews or heretics.Footnote 114 Ruiz de Montoya's proposal also included the creation of a bishopric in Rio de Janeiro. This modification, together with the creation of an Inquisition tribunal, would signify a powerful intervention by the Spanish crown in the administration of Brazil, indicating a future legislative unification of Portuguese and Spanish America.

An Illustrious Predecessor and Collaborator

The notion of a bishopric in Rio de Janeiro was not new, and in fact the idea had already been presented by Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça in a 1631 memorial.Footnote 115 Born in the Portuguese city of Sesimbra in 1585, Mendonça had joined the Society of Jesus in 1602 but was expelled at some point before arriving in Peru in 1615.Footnote 116 He studied law and theology, earned a doctorate, and was ordained a secular priest. As a member of the Holy Office, he exercised various functions in Peru, including serving as commissioner of the Inquisition in Potosí. He also served as a missionary in the Chichas region and visitador to Paraguay.Footnote 117

Mendonça was a prolific petitioner whose proposals had reached the Council of the Indies numerous times. In 1629, he informed the court in Madrid that he had organized the native labor force of the mines of Tatasi, Chorolque, San Vicente, San Francisco, Monserrate, Chocaya, and Sorocaya (located in present-day Bolivia). He requested as a prize the accumulated wages of ten years, which he believed amounted to more than 10,000 ducats. Initially, Mendonça presented himself as an expert in mining matters, including fiscal issues and new methods for increasing the production of Potosí and other alluvial mines.Footnote 118 In another petition, he even proposed a safer route for conveying Peruvian silver to Spain.Footnote 119

While visiting the border between Paraguay and São Paulo in 1625, Mendonça witnessed the harm done by the Paulistas among the natives of the region.Footnote 120 He had requested the bishopric of Chile for himself, a prize he did not receive. Instead, he obtained the prelacy of Rio de Janeiro, a position he held from 1632 to 1637, albeit with great difficulty in the face of continuous threats from the region's inhabitants.Footnote 121

Knowing firsthand the problems Portuguese slavers had caused in that region, Mendonça hoped to come to Rio de Janeiro as a bishop with inquisitorial powers.Footnote 122 In his 1631 memorial, he described his reasons, claiming that the Paulistas went to Paraguay or the Río de la Plata under the pretext of joining the holy orders, only to return with indigenous slaves.Footnote 123 His main argument in favor of a bishopric in Rio de Janeiro, however, was that its territory was so vast that it could not be administered from Salvador. To support his argument, he described the geographic and economic situation of the prelature of Rio de Janeiro in the memorial: although it was a poor region with a small population, it was not as poor or as sparsely populated as some others, such as São Tomé, Ceuta, and Cape Verde, which already counted bishoprics. The tithes obtained from Rio de Janeiro yielded 50,000 ducats, no trivial sum. To avoid having to draw the future bishop's salary from other sources of the royal hacienda, he recommended earmarking part of the customs revenues. In fact, Rio de Janeiro was quite a large territory, spanning 400 leagues of coast and 300 leagues inland, seven captaincies, and 20 Portuguese cities, as well as numerous indigenous villages—all with difficult communication with Bahia and extensive trade with Angola and Río de la Plata.Footnote 124

Mendonça pointed out other problems that a bishopric could address. First, there was the great shortage of priests, which forced Rio de Janeiro to accept priests who were “New Christians, suspicious and of little satisfaction in the things of our holy faith,” individuals of dubious conduct from Portugal, and even fugitives from the Río de la Plata and Peru. Second, and more important, a bishop was needed in Rio de Janeiro to act as inquisitor, since there were already many of suspect faith. In this respect, Ruiz de Montoya's proposal was not at all original.Footnote 125

By 1599, there were already numerous proposals recommending that the Habsburgs incorporate the administration of Brazil, or at least the southern part of it, into direct government by Madrid. That year, the governor of Buenos Aires, Diego de Valdes y de la Vanda, reported his observations from the Brazilian coast to the court. He claimed to have seen a good number of English and Dutch married couples in Rio de Janeiro, which he learned was common in other parts of Brazil. He had heard that Portuguese sugar producers were sending their merchandise to Europe in Dutch, English, and German ships, by both legal and illegal means, and that English ships were conducting important business in São Vicente and Bahia. He considered it very advantageous to place a Castilian government in those provinces and reduce them to the crown of Castile, “to which they truly belonged,” and proposed that a fleet of six armed galleons escort the convoys of ships between Lisbon and Brazil, in the style of the silver fleet system, so that the English and Dutch enemies would no longer frequent those parts.Footnote 126

The Spanish crown's attitude toward the bandeiras and indigenous slavery had until then been remarkably complacent. In 1611, yielding to pressure from Portuguese slavers, Philip III weakened the substance of an earlier law on indigenous freedom and allowed slavery by “just war,” provided it was approved by the Board of Missions, a local council composed of religious and civil authorities. He also established that natives residing in villages should work for the settlers as long as they received wages, but this point was ostensibly ignored.Footnote 127 A royal cédula of September 12, 1628, ordered the governor of the Río de la Plata to repress the bandeiras, but gave no details on how the Spaniards would apprehend the delinquents, and nothing regarding this was communicated to the authorities in Portugal or Portuguese America.Footnote 128 The Council of the Indies downplayed the 1631 proposals for a bishopric in Rio de Janeiro and suggested asking the bishop of Bahia for more information and renewing the ban on Portuguese taking holy orders in Río de la Plata.Footnote 129 This attitude remained unchanged until 1639.

The similarity between Ruiz de Montoya's and Mendonça's projects and the collaboration between the two may have favored their positive reception at court. Mendonça had actively advocated for the jurisdictional unification of Iberian domains since at least 1630—at a time when criticisms of Olivares's Union of Arms were emerging in Portugal and Catalonia. In another paper submitted that year, Mendonça reported that the Portuguese living in Spanish America were being forced to pay unfair taxes as a result of a 1618 cédula and argued that instead the crown should give more equitable treatment to all subjects of the monarchy regardless of their place of origin.Footnote 130

Mendonça had been a severe and intransigent critic of indigenous slavery during his nearly five years as prelate of Rio de Janeiro. He reported that he received continuous death threats, and that one night some men threw a barrel of gunpowder into the room where he was sleeping, blowing up his house, from which he incredibly escaped unharmed.Footnote 131 His departure from that city in 1637 gave cause for speculation, but Madrid clearly accepted that the ouvidor and the town council conspired to expel him from the city.Footnote 132

The crown took Ruiz de Montoya's memoriales very seriously. Philip IV appointed a special junta composed of six councilors: from the Council of the Indies, Juan de Solórzano Pereira and Juan de Palafox; from the Royal Council, Sebastián Zambrano; from the Council of Portugal, Cid Almeida and Francisco Pereira Pinto; and the bishop of Porto, Gaspar Rego da Fonseca. Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça, then prelate in Rio de Janeiro, assisted in the work.Footnote 133 Ruiz de Montoya later told a colleague that he “had many conversations with the Count-Duke [of Olivares] about the Portuguese, the Indians and the things of that province.”Footnote 134 After several sessions in which Ruiz de Montoya and Mendonça's papers were discussed, Juan de Palafox composed the consultation to the king.Footnote 135

As these discussions were taking place, Ruiz de Montoya published his celebrated Conquista espiritual in 1639. According to the author, Juan de Palafox asked him to write this work. Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça examined the book and granted ecclesiastical approval.Footnote 136 Mendonça also read Ruiz de Montoya's linguistic works, correcting and inserting errata in them, as well as giving his ecclesiastical approval.Footnote 137 Conquista espiritual consists of 81 chapters and is divided into four parts: the first describes the province of Paraguay; the second deals with the province of Guairá, with emphasis on the Paulista attacks and the forced exodus of 1631; the third describes the reductions in general; and the fourth deals with the missions in their current situation and discusses priests’ martyrdom.Footnote 138 Denunciations against the bandeirantes abound in the work, which is undoubtedly one of the most important chronicles of the Jesuit experience in the Americas. Ruiz de Montoya admitted, however, that he had written the book in a hurry. Dictated to a scribe, the work preserves the nonliterary tone of the annual letters.Footnote 139

Ruiz de Montoya's success as a procurator in Madrid was undeniable. The crown accepted his proposals and on September 16, 1639, promulgated a royal cédula addressed to the viceroy of Peru, with copies sent to nearby governors. The cédula reproduced most of the points contained in Ruiz de Montoya's memorial as royal mandates.Footnote 140 The decree stated that the king had learned of the Paulista hostilities and ordered an armed contingent to defend the missions. It was reported that the Paulistas had captured up to 300,000 souls; thus their actions constituted a transgression of the law on indigenous freedom promulgated in Lisbon in 1611.

Those who enslaved natives were to be punished with the confiscation of property, loss of all privileges and honors, and perpetual banishment from Brazil. To ensure compliance with the law of 1611, Philip IV ordered the creation of a Tribunal of the Holy Office in Rio de Janeiro with full powers. The decree also incorporated Ruiz de Montoya's suggestion to repatriate enslaved indigenous people to Paraguay, except for those who where were married or elderly. In such cases, they were to be relocated to villages within Brazil. Additionally, the decree provided a list of individuals who were to be immediately apprehended and sent to appear before the Council of the Indies. These individuals included Raposo Tavares and Federico de Melo, as well as friars Antonio de San Esteban (Carmelite) and Francisco Valladares (Benedictine), and secular priests Juan de Campo y Medina, Francisco Jorge, and Salvador de Lima.Footnote 141

The legislation drafted in 1639 outlined a plan for the legal unification of the Spanish empire. Madrid proposed intervening in Portuguese America by establishing a bishopric and an Inquisition tribunal to suppress the activities of the bandeirantes. Individuals involved in enslaving natives would face harsh penalties and be sent to Madrid. This was the first time that Iberian royal officials considered granting indigenous freedom in both Portuguese and Spanish America, a concept that the Portuguese did not definitively adopt until 1755. Significantly, this law applied to anyone engaged in indigenous slavery, whether in Brazil, Portugal, Africa, or the Spanish Indies, thereby representing a legal standardization of these areas.

In 1639, the Council of the Indies received information about the presence of Portuguese in other border areas of the Spanish domains. In a letter sent on November 18 of the previous year, the president of the Audiencia of Quito reported that Portuguese captain Pedro Teixeira had arrived in that city, coming from Pará via Amazonian rivers. Teixeira escorted Fray Domingo Brieva, one of the Spanish Franciscan missionaries who had appeared in Pará fleeing a native rebellion, back to Quito. The governor of Pará had sent the other fray, Andrés de Toledo, to Madrid.Footnote 142 The Council of the Indies also received a complaint from the governor of Caracas that the Portuguese were entering Spanish Amazonia, taking natives as slaves and eventually appearing in that city to sell them. At the time, Madrid was reinforcing its prohibitions on indigenous slavery and preparing for a major institutional intervention in Portuguese domains, and the letter from the governor of Caracas was received with indignation. Madrid ordered “that the said Jacome Raimundo de Noronha, governor of the provinces of San Luis del Marañón, be severely reprimanded and punished for having dared without consultation and license . . . to make the said entradas and navigations and uncover the breasts of Peru, which although they were very near, we should try to cover up and erase from the memory of men.” It is interesting to note that in advancing in the process of institutional unification, the Council of the Indies determined the punishment of a Portuguese governor.Footnote 143

There was some contention, however, about who would be the new bishop of Rio de Janeiro. Ruiz de Montoya had proposed Dominican Juan de Vasconcellos, inquisitor of the Supreme Tribunal of Portugal, but the councilor of Portugal, Francisco Pereira Pinto, insisted that the new bishopric was a “small post for such a great person.”Footnote 144 In the end, Philip IV appointed Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça, on October 7, 1639. Mendonça was in Lisbon with Ruiz de Montoya on December 1, 1640, awaiting the arrival of the papal bulls, when the movement to acclaim John IV as the new king of Portugal succeeded. Ruiz de Montoya and Mendonça returned to Madrid.Footnote 145 The bishopric of Rio de Janeiro was only created again within the Portuguese empire on November 16, 1676.

Although Ruiz de Montoya and Mendonça acted as arbitristas while they were in Madrid, they collaborated with each other rather than exchanging hostilities, as arbitristas normally did with their rivals. Ruiz de Montoya was in Rio de Janeiro in 1637, and the two likely returned to Europe together; they were both in Madrid between 1638 and 1639. Mendonça collaborated closely with Ruiz de Montoya's writings and petitions. Both stood to gain if the crown approved their projects: one would become bishop and the other would obtain security for the Jesuit missions. The crown certainly took this into account, as they did the fact that both men knew the region of which they spoke intimately and were united in their proposals. All these factors, I believe, contributed to Philip IV's decision to make an important administrative intervention in the Spanish empire in the South Atlantic, a reform that in practice meant the legislative unification of the two Iberian dominions.

Epilogue

After Portugal declared independence, Ruiz de Montoya concentrated his efforts on several other fronts. In his subsequent petitions, he requested firearms for the Guaraní, an Inquisition presence in the Río de la Plata, and a moderate indigenous tribute.Footnote 146

Meanwhile, the Paulistas continued their attacks on the missions; their 1636 expedition destroyed three missions in Uruguay and enslaved hundreds of natives.Footnote 147 These events impelled Ruiz de Montoya to request more firearms for the Guaraní. The notion of granting firearms to the Guaraní was not new. As we have seen, Céspedes had made public the fact that the Jesuits were arming the natives without a license in 1629.Footnote 148 In 1638–39, Paraguay was devastated by incursions led by Fernão Dias Paes. In January 1639, the governor of Paraguay, Pedro de Lugo y Navarra, led a troop of 70 Spaniards against the Portuguese. In the battle of Caazapá-guazú, the governor gave firearms to the Guaraní, who were commanded by Jesuit Antonio Bernal, a religious who had served as an officer in the Chilean wars. At a certain point during the battle, the governor thought it prudent to withdraw his men, while Bernal and his natives continued to fight and prove their superiority against the enemy. Nine Portuguese died in this conflict. The Guaraní captured 17 Portuguese and recovered 2,000 enslaved natives. After a few days, however, the governor released the prisoners and rebuked the Guaraní, to the Jesuits’ great consternation.Footnote 149

Following the success of the Guaraní in defending themselves with firearms, both the Jesuits and ecclesiastical authorities in Asunción petitioned for a royal permit.Footnote 150 The Jesuits sent two petitions requesting a license for natives to use firearms in 1639. Quoting an extensive body of juridical and theological authorities, the Jesuits claimed that natural law did not prohibit firearms, but permitted their use for the just defense of life, country, and Church, and that even when positive law prohibited clerics from using weapons, this prohibition ceased to apply in urgent cases.Footnote 151 Between March 11 and 18, 1641, the Paulistas suffered another important defeat, this time in the battle of Mbororé, which occurred near the confluence of the Mbororé and Uruguay rivers. Under the guidance of Brother Domingo de Torres, 3,000 Guaraní warriors surrounded the 400 Paulistas and their 2,500 Tupi auxiliaries and attacked them by surprise.Footnote 152 The Paulistas waited another nine years before they attempted another attack on the region.Footnote 153

Like other petitioners of his time, Ruiz de Montoya was requesting authorization for a practice that was already taking place without a license. He requested 500 firearms, 70 containers of gunpowder, and as many quintals of lead.Footnote 154 The success of the Guaraní military actions induced royal officials in Peru and Madrid to look favorably on supplying firearms to natives. In a 1642 cédula, Philip IV delegated the final decision to the viceroy of Peru. The viceroy consulted local authorities and decided to send the arms in 1646. Forty firearms would be given to each pueblo, and the natives would receive training from Jesuit brothers who served in the kingdom of Chile.Footnote 155

As early as 1644, Ruiz de Montoya could cite the first victories against the Paulistas that were accomplished with the use of firearms by the Guaraní.Footnote 156 The Guaraní also obtained a good number of firearms from the Paulistas they were defeating.Footnote 157 Thus equipped, the Guaraní also consolidated their status as militiamen of the Paraguayan government and were sent on expeditions against enemy native groups, especially the Calchaquí, Guaykuru, and Neenga.Footnote 158

The Guaraní militias had a formal organization similar to European ones. One witness stated that the natives had spears, pikes, flags, drums, and even masons, and that they had reserved every Sunday for conducting their alardos (military exercises), in which they practiced European-style war maneuvers.Footnote 159 Recent studies have revealed a shift in Guaraní perceptions of leadership as they experienced mission-governing institutions, including the cabildos and, notably, the militias.Footnote 160 The Guaraní militias continued to render valuable services to the government of Paraguay, such as the defense of the province against the Chaco natives; the repair of prisons and fortifications in the province and even the construction of new ones; and defense against the Portuguese.Footnote 161 Although the Guaraní received no salary for such services, the Jesuits continued to attend punctually to the colonial authorities’ requests. They could then include reports of these services to Madrid in support of their own petitions.Footnote 162

In his 1641 memorial, Ruiz de Montoya proposed the establishment of an Inquisition tribunal in either Buenos Aires or Córdoba. His argument stemmed from the Portuguese attempts to reach Potosí. While the Guaraní were preventing their passage through the missions, Buenos Aires remained vulnerable, as the Portuguese were allegedly spreading anti-Catholic doctrine. Thus, it became imperative to station one or two inquisitors there.Footnote 163 By 1643, the population of Buenos Aires included a significant number of Portuguese individuals, accounting for approximately 25 percent of the total.Footnote 164 However, the Council of the Indies deemed an Inquisition tribunal too costly to maintain in a region as peripheral as the Río de la Plata.Footnote 165

The last attempts Ruiz de Montoya made as procurator were aimed at achieving a reasonable and fair taxation for the indigenous people of the missions.Footnote 166 The information provided by the Jesuits about the damage that continuous Portuguese invasions had done to the missions and their “resources, buildings, and crops” led the king to grant natives ten additional years of tax exemption in 1643.Footnote 167 In yet another memorial, Ruiz de Montoya proposed a tribute rate of one peso per year per native for the Guaraní, while emphasizing their invaluable military service as a form of credit they were accumulating by supporting the monarchy: “If tribute and mitas were to be imposed on the said Indians, overloading them with the burden they have today of maintaining the war against the rebels, irremediable damage could be feared.”Footnote 168

Ruiz de Montoya's performance as procurator was fundamental to the consolidation of Jesuit missions in Paraguay. Deeply knowledgeable of the territory and its problems, and the political intricacies at play in the South Atlantic, Ruiz de Montoya received, classified, distilled, and channeled the flood of information and requests that arrived from Paraguay to bring them to the attention of the Madrid court and to have proceedings address them. The success of his work is undeniable, since almost all of the memoriales he presented were approved and resulted in laws. In addition, he used his time at court to publish his works, which became an obligatory reference for those interested in the missions. Ruiz de Montoya returned to Lima around 1643 and died there nine years later. His life was closely linked to the Paraguayan missions, and he even requested that his remains be buried in the mission of Loreto.Footnote 169

Ruiz de Montoya, along with Lourenço Hurtado de Mendonça, proposed not only the protection of the natives but also a significantly greater integration of the Iberian domains compared to what the Cortes of Tomar had established. While both men acted as solo petitioners in Madrid, they also collaborated on projects that gained favorable attention from the crown due to their intimate familiarity with the realities they addressed. Perhaps more importantly, Ruiz de Montoya went beyond the typical activities of religious order lobbyists and embraced the role of an arbitrista—a proponent of reforms for the empire—an aspect of his trajectory that was previously little-known. By doing so and with the collaboration of other Jesuits and the clergyman Mendonça, he successfully captured the crown's attention to address the issue of indigenous slavery in the South Atlantic. The success of his proposals certainly boosted the Society of Jesus's power and influence within the Spanish empire thereafter.

In the midst of these events, the Jesuits also collected enemies. Writing in 1643, Ruiz de Montoya presented a memorial defending the Jesuits against some defamatory papers that were circulating in Madrid. The accusations purported that the Jesuits were exploiting an important treasure they had hidden in Paraguay; that they encouraged enmity between natives and Spaniards; that they did not allow bishops and other authorities to visit their missions; and that they were preventing natives from working for encomenderos. Ruiz de Montoya carefully refuted each of these points, building a case for the Society of Jesus's loyalty to the monarchy.Footnote 170 In this he certainly succeeded, as evidenced by the important concessions the crown made to the Jesuits during this crucial period in the establishment of the missions.