A majority of Western European countries have seen a large increase in the number of immigrants in recent decades. In many EU countries, the number of foreign-born individuals as a share of the population has come to exceed 10% and is in some cases approaching 15% or higher (Eurostat 2020). At the same time, the rise of anti-immigration parties constitutes one of the largest changes to the European political landscape, as an increasing share of voters now support anti-immigration and protectionist policies. A causal relationship between increased support for these types of parties and a higher influx of immigrants, especially from non-European countries, is often suggested in academic debates: in other words, natives are believed to oppose immigration when they are exposed to immigrants and refugees.

Yet, it is likely that certain conditions influence the effects of increased exposure to immigrants with regard to voting for anti-immigration parties, such as the skill level of immigrants (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile and Hahn2019) or the socioeconomic status among natives (Strömblad and Malmberg Reference Strömblad and Malmberg2016). An additional important aspect is the type of intergroup contact associated with an influx of immigrants. According to the classic contact hypothesis (Allport Reference Allport1954), extensive and cooperative interactions between majority and minority groups can undermine prejudices and/or negative sentiments about members of minority groups. At the same time, superficial contact might instead have an adverse effect on prejudices toward minority groups. Indeed, studies finding a positive association between exposure to immigrants and opposition to immigration often capture superficial contact (Becker and Fetzer Reference Becker and Fetzer2016; Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Knigge Reference Knigge1998; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002), while meaningful contact, typically cooperation between majority and minority group members, has been shown to reduce prejudice (Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Hanson, Johnsen, Kotsadam and Torsvik2019; Finseraas and Kotsadam Reference Finseraas and Kotsadam2017; McLaren Reference McLaren2003; Mousa Reference Mousa2019; Simonovits, Kezdi, and Kardos Reference Simonovits, Kezdi and Kardos2018; Steinmayr Reference Steinmayr2020).Footnote 1

This study focuses on the workplace, which facilitates cooperative contact between majority and minority group members. Due to this feature, it serves as a social arena in which interactions are expected to help reduce opposition to immigration, in line with the contact hypothesis. However, immigrants in the workplace may also reinforce natives’ fear of increased competition for higher wages and employment, as predicted by the ethnic competition hypothesis. For these reasons, an increased presence of immigrants in the workplace potentially has both positive and negative effects on voting for anti-immigration parties. The cooperative and repetitive nature of meaningful workplace contact is expected to reduce negative sentiments toward immigrants, whereas a high share of foreign-born coworkers might signal to native workers that their employment status is threatened. Thus, the overall effect of contact in the workplace could yield mixed results. Despite being one of our most important arenas for social interactions, to the best of our knowledge, there are no large-N empirical studies addressing this particular question.

We examine the consequences of workplace contact between native-born and non-European workers in terms of support for anti-immigration parties. Our focus is Sweden, which offers an interesting setting due to (1) high-quality administrative data and (2) a high and, for a long time, growing share of foreign-born individuals in the workforce. We use a full population Swedish dataset that includes demographic and socioeconomic information on all legal residents, while also linking all employed residents to a unique workplace. This allows us to compute the share of coworkers with a non-European background for each native-born worker. These individual-level shares are aggregated at the election precinct level and matched with election outcomes for the largest Swedish anti-immigration party, the Sweden Democrats (SD) in the national elections in 2006, 2010, and 2014. Our research design allows us to estimate the effect of precinct-level workplace contact on support for SD.

We find large and statistically significant negative effects of the workplace share of non-Europeans on support for SD. In our preferred specification, a one-standard-deviation increase in the average share of non-European coworkers among resident natives decreases the share of votes for SD in the election precinct by more than 0.4 percentage points, or roughly 8% of the standard deviation in the outcome. An extensive set of sensitivity checks corroborate the estimated negative effect.

We further extend our baseline result with a number of auxiliary analyses and reach the following conclusions. First, increased workplace contact between natives and non-Europeans results in a decreased support for SD, which is in line with the contact hypothesis (Allport Reference Allport1954). This suggests that overall intergroup workplace contact is characterized by meaningful contact. Several features of the workplace allow contact to lower the level of opposition to immigration. Workers usually interact repeatedly over longer periods and work together toward a common goal.

Second, we find that the negative relationship between workplace contact and opposition to immigration is solely driven by same-skill contact. This means that any potential positive effect of same-skill labor market competition on voting for anti-immigration parties is offset by the effect of meaningful workplace contact between coworkers. At the same time, the presence of different-skill non-European coworkers has no statistically significant effect on opposition to immigration. Since many workplaces exhibit low levels of vertical integration, we expect contact to primarily occur within the same skill level.

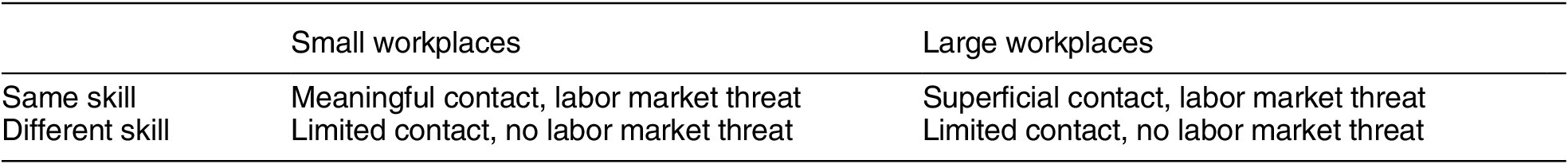

Third, we categorize workplaces based on their size and find that same-skill contact in small workplaces has a negative effect on opposition to immigration, while the opposite effect is estimated for same-skill contact in large workplaces. Exposure to non-European coworkers in the latter setting does not offset the positive influence of fear of same-skill labor market competition on opposition to immigration. Therefore, contact in this setting lends support to the ethnic competition hypothesis. When considering contact with different-skill non-European coworkers, the estimates are statistically indistinguishable from zero regardless of workplace size. These results suggest that superficial contact only leads to opposition to immigration when there is a threat of increased labor market competition. In other words, both superficial contact and the threat of same-skill labor market competition are necessary but not sufficient conditions for workplace contact with foreign-born coworkers to result in higher support for anti-immigration parties.

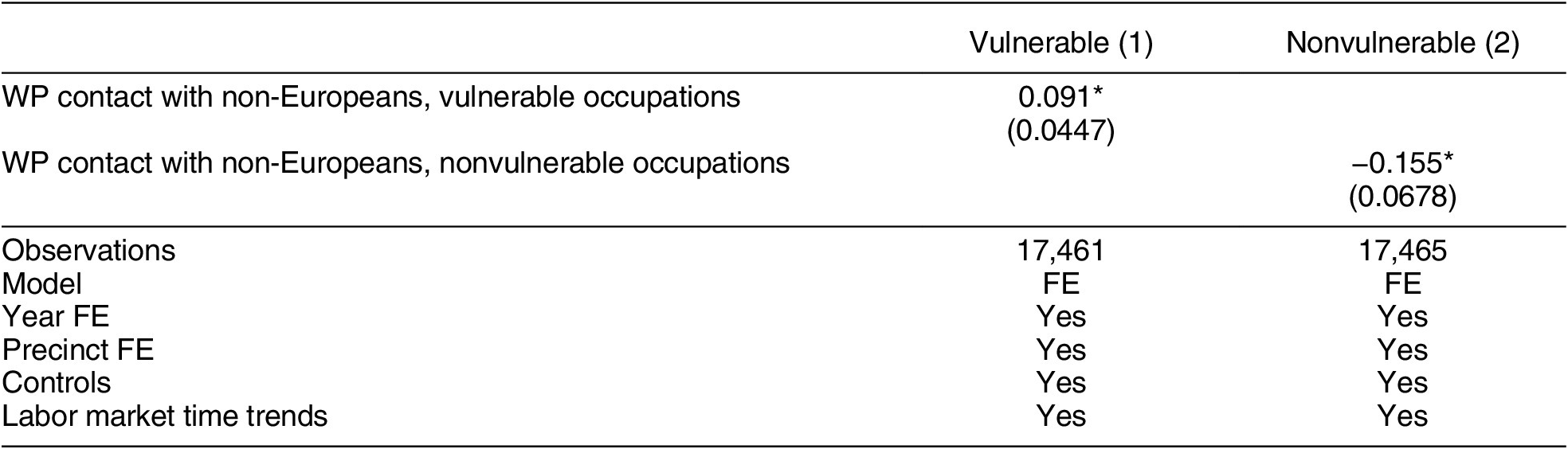

Finally, we provide suggestive evidence of a negative association between workplace contact and votes for SD only among workers employed in occupations characterized by a low risk of experiencing job loss. A possible interpretation of these results is that labor market competition from immigrants becomes more salient for natives when the natives’ occupation is vulnerable and there is a greater risk of job loss.

Our results add to the extensive scholarship on the emergence and success of anti-immigration and radical right parties. This literature mainly focuses on two explanatory variables: economic conditions and immigration. In both cases, however, the evidence is inconclusive as some studies find economic distress (e.g., job separations, unemployment rates) and exposure to immigrants to be positively correlated with voting for anti-immigration parties, while other studies find the opposite or no correlation. Specifically, we add to the literature concerning exposure and contact with immigrants and how these affect support and demand for anti-immigration policies. Most studies in this field of scholarship rely on measures of local, regional, or national shares of immigrants in addition to either aggregated vote shares or survey data on anti-immigration attitudes. In most cases, the types of interactions that exist between majority and minority group members are unknown. We add to the literature by specifically considering interactions between coworkers in the workplace.

We also relate to the literature on the perceived increase in labor market competition facing natives as a result of same-skill immigration. Native workers with a particular skill are expected to lose from the immigration of people with the same skill, as this raises the level of competition for jobs and lowers the relative wages for the same skill level (Borjas et al. Reference Borjas, Freeman, Katz, DiNardo and Abowd1996; Reference Borjas, Freeman, Katz, DiNardo and Abowd1997). We show that the positive influence of fear of labor market competition on opposition to immigration can be offset by meaningful workplace contact, thus in support of the contact hypothesis.

Theoretical Background and Related Research

The Sweden Democrats were founded in 1988 by former members of the neo-Nazi party the Sweden Party. The party had limited electoral success during its first decade, which led to a rebranding process in the late 1990s, and the party received 1.4% of the votes in the 2002 national election. Eight years later, SD entered the Swedish parliament for the first time after receiving 5.7% of the cast votes, resulting in 20 seats. In 2014, the party became the third-largest party in Sweden by receiving close to 13% of the cast votes.

SD presents itself as a social conservative, anti-immigration party, and its supporters have been shown to view immigration as one of the most salient political issues (Rydgren and Van der Meiden Reference Rydgren and Meiden2019). It thus seems natural to assume that the consequence of increased immigration is higher support for SD, and there are several hypotheses predicting this. Indeed, a large number of studies provide evidence of a positive association between immigration and support for anti-immigration parties in many European countries (for instance, Becker and Fetzer Reference Becker and Fetzer2016; Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Knigge Reference Knigge1998; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Valdez Reference Valdez2014). A popular explanation for this relationship is that natives fear that their social status and identity will be challenged as they are exposed to ethnic minorities (group positioning theory). This means that natives in neighborhoods with a high share or large influx of immigrants are more likely to oppose immigration, which subsequently leads to higher support for anti-immigration parties.

Similarly, the ethnic competition hypothesis argues that opposition to immigration among natives is based on their fear of competition for employment, housing, and general social welfare between in-group and out-group members. One can imagine that this fear intensifies following a large influx of immigrants, which leads to increased opposition to immigration. The fear of competition for economic resources can be split into two parts: (1) fear of reduced access to welfare services and benefits and (2) fear of competition for employment and high wages.Footnote 2 In terms of the latter factor, it seems reasonable that the presence of immigrants in one’s workplace highlights the threat of competition to a greater extent than by observing them in your neighborhood. Thus, we identify the following prediction in line with the ethnic competition hypothesis:

Prediction 1. An increased presence of foreign-born workers in the workplace highlights the threat of competition for employment and high wages, thereby increasing opposition to immigration.

However, the expected competition between natives and immigrants depends on the skill level of the members of the two groups. According to the factor-proportion analysis model (see, for instance, Borjas et al. Reference Borjas, Freeman, Katz, DiNardo and Abowd1996; Reference Borjas, Freeman, Katz, DiNardo and Abowd1997), natives with a particular skill level are expected to be worse off from the immigration of people with the same skill level, as this increases the relative supply of workers with this particular skill level and lowers their relative wages.Footnote 3 This suggests that the existence of same-skill foreign-born coworkers has a stronger effect on opposition to immigration. We thus identify an augmented prediction:

Prediction 1.1. An increased presence of same-skill foreign-born workers in the workplace is more likely to highlight the threat of competition for employment and high wages, thereby increasing opposition to immigration.

A different relationship between the presence of immigrants and opposition to immigration is predicted by the contact hypothesis (Allport Reference Allport1954), which argues that intergroup contact may reduce prejudice. Instead, an increased presence of immigrants predicts a lower support for anti-immigration parties. However, the type of contact is crucial in terms of how it influences prejudice. Allport (Reference Allport1954) notes that cooperation between members of in-groups and out-groups reduces negative sentiments, while prejudice may increase from superficial or casual contact. It is further argued that contact is more likely to reduce prejudice if it occurs at an equal level, is repetitive, and works toward a common goal. In accordance with the contact hypothesis, we identify the second prediction:

Prediction 2. An increased presence of foreign-born workers in the workplace leads to meaningful intergroup contact, which, in turn, reduces prejudice toward minorities and opposition to immigration.

Since teamwork dominates the modern labor market (Hamilton, Nickerson, and Owan Reference Hamilton, Nickerson and Owan2003), the workplace is likely to satisfy the conditions under which intergroup contact reduces opposition to immigration. This is particularly true for interpersonal contact between coworkers with the same skill. Imagine a firm employing both low-skill and high-skill workers. At one of this firm’s workplaces, all employees potentially interact at, for instance, the workplace cafeteria. However, since workers with the same skill perform similar tasks, they are more likely to encounter each other frequently in the workplace. This means that there is a larger opportunity for meaningful and cooperative contact. Same-skill workers are also more likely to share similar backgrounds and experiences and to consider each other as being equals. Same-skill contact with foreign-born coworkers is thus more likely to reduce opposition to immigration, contrary to the consequences of an increased presence of same-skill immigrants formulated in Prediction 1.1.

This study examines the effect of workplace contact between natives and their non-European-born coworkers on support for SD. The ethnic competition hypothesis and the contact hypothesis predict effects going in opposite directions, and the net effect is ambiguous. Our main analysis considers the overall workplace contact between natives and workers born outside Europe, and we extend the analysis to same-skill and different-skill contact. It is important to note that our analyses do not allow us to reject any of these hypotheses with certainty. A positive net effect of intergroup contact in the workplace on opposition to immigration lends support to the ethnic competition hypothesis, while the opposite effect supports the contact hypothesis. Still, the consequences of workplace contact with regard to opposition to immigration could differ depending on the workplace environment. While some native workers might engage in meaningful workplace contact with their immigrant coworkers, others might view immigrants as a threat to their labor market position. Although the net effect of overall workplace contact might be negative, both hypotheses could still be valid.

In addition, workplaces with a certain set of characteristics might facilitate more of one specific type of contact. One example is same-skill contact where a closer and more meaningful form of contact is to be expected. The net effect in a workplace environment characterized by same-skill contact might differ compared with other environments.

Another important aspect potentially influencing the type of workplace contact is the social and economic status of the members of the majority group. According to Allport (Reference Allport1954), one needs to consider whether an individual engaging in contact with, for instance, an ethnic other has “basic security in his own life, or is […] fearful and suspicious” (263). An important basic security is natives’ labor market position: the fear of being separated from their jobs (e.g., due to globalization or technological change) can affect how natives react to foreign-born coworkers.Footnote 4 In occupations where the expected job loss is at a very low level, an increased share of immigrants in the workplace in the same occupation is arguably less of a threat to natives compared with occupations where separation or turnover is high. This leads to a final prediction:

Prediction 3. The threat of increased competition for employment and high wages with foreign-born workers is only highlighted among native workers employed in vulnerable occupations.

Empirically, the aforementioned studies on the association between exposure to minorities in one’s neighborhood and voting for anti-immigration parties point in the same direction—namely to increased support for such parties.Footnote 5 However, a recent wave of research provides evidence of reduced prejudice due to intergroup contact in a large variety of settings.Footnote 6 For instance, a three-week camp for Israeli and Palestinian teenagers was found to improve the participants’ out-group attitudes (Schroeder and Risen Reference Schroeder and Risen2016). Mousa (Reference Mousa2019) shows that Iraqi Christians randomly assigned to soccer teams consisting of both Christians and Muslims were more likely to interact with Muslims in the future. Finseraas and Kotsadam (Reference Finseraas and Kotsadam2017) and Finseraas et al. (Reference Finseraas, Hanson, Johnsen, Kotsadam and Torsvik2019) use a field experiment where Norwegian soldiers were randomly assigned to share rooms with ethnic minorities. The former study finds that contact with ethnic minorities reduced negative stereotypes regarding immigrants’ work ethics, while the latter study finds that intergroup contact increased trust toward immigrants. The setting in these two studies resembles the workplace, as the recruits were working closely together and had to cooperate in order to solve tasks.

The social settings in these studies encompass a much closer and more meaningful contact than the superficial contact one would expect from minorities simply being visible in the neighborhood, and they do not highlight intergroup competition for economic resources. In these types of settings, the effect of contact is less ambiguous.

So far, we have described the conditions under which meaningful contact can occur without discussing the empirical evidence of the existence of these conditions. Is there any corroborating evidence of workplace settings facilitating the type of contact required for reducing prejudice? If so, what characterizes these settings? Several studies have noted that interactions in the workplace differ from those in other contexts. For instance, Mutz and Mondak (Reference Mutz and Mondak2006) emphasize how a larger portion of the day is spent in the workplace compared with other organizations or the neighborhood. Furthermore, almost all jobs “require contact with coworkers or customers” (Mutz and Mondak Reference Mutz and Mondak2006, 141). Kokkonen, Esaiasson, and Gilljam (Reference Kokkonen, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014) add that cooperation between colleagues is essential for achieving work-related tasks and that individuals are “typically assigned to interact with colleagues who they have not chosen themselves” (269). Opting out from such tasks is costly as this might lead to displacement.

In other words, the workplace facilitates frequent and cooperative contact between coworkers who would not necessarily interact in other contexts. This contact fulfills several of the conditions set up by the contact hypothesis and is thus positioned to reduce prejudice.Footnote 7 Kokkonen, Esaiasson, and Gilljam (Reference Kokkonen, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014) note that one of the conditions might not be fulfilled, namely equal status between members of the in-groups and out-groups.Footnote 8 This highlights the importance of also considering same-skill workplace contact, where coworkers are arguably equal in status.

The relationship between intergroup workplace contact and prejudice is examined in a small number of studies using survey data on self-reported interactions with minority members or the presence of immigrant coworkers. While the outcome of interest is typically ethnic prejudice (Quillian Reference Quillian1995; Strabac Reference Strabac2011; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Christ, Pettigrew, Stellmacher and Wolf2006), Escandell and Ceobanu (Reference Escandell and Ceobanu2009) measure foreign exclusionism and Thomsen (Reference Thomsen2012) examines attitudes toward ethnic minority rights. The latter study uses Danish survey data to show that perceived group threat is weakened by intergroup workplace contact, which, in turn, leads to higher ethnic tolerance. Thus, the study specifically examines whether workplace contact reduces the perception of a threat imposed by members of other ethnic groups. This is directly related to the predictions formulated in this study, with one exception. Thomsen (Reference Thomsen2012) does not specify in which contexts the threat emerges nor which type of threat perception is weakened as a result of contact. For instance, workplace contact might reduce perceptions of a threat to social status caused by exposure to immigrants in the neighborhood.

We argue that the presence of immigrants in the workplace first and foremost highlights the threat of increased labor market competition, which, in turn, can affect the possibility of meaningful intergroup workplace contact. In particular, competition is likely to influence natives’ feelings towards cooperation with their immigrant coworkers. For instance, natives who fear increased labor market competition might be predisposed to avoid collaborative contact with their immigration coworkers simply due to feelings of mistrust towards those they perceive as being their competitors (cf. Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Hanson, Johnsen, Kotsadam and Torsvik2019). Another possibility is that natives refrain from cooperation that benefits both sides to avoid improving the labor market competitiveness of their immigrant coworkers.Footnote 9 In both cases, prejudice-reducing intergroup contact will be affected. In workplace contexts with a strong fear of labor market competition with immigrants, the perceived group threat is likely to impede cooperative contact, resulting in increased opposition to immigration.

A substantial body of literature examines perceived group threat as resulting from interactions between majority and minority group members in neighborhoods. However, less is known when it comes to intergroup conflict in the workplace. Bonacich (Reference Bonacich1972) argues that antagonism between ethnic groups can be caused by large differentials in the price of labor, a so-called split labor market. In these situations, high-price labor—typically natives—will try to prevent low-price labor—typically ethnic minorities—from entering the labor market. This occurs as high-price labor fears being displaced in favor of cheaper labor. It seems plausible that the presence of ethnic minorities in the workplace highlights group-level competition for employment and high wages. Dixon and Rosenbaum (Reference Dixon and Rosenbaum2004) note that workplaces “dually encourage collaboration and competition” (261). While collaboration is in line with our second prediction, competition speaks to the first.

Similarly, Laurence, Schmid, and Hewstone (Reference Laurence, Schmid and Hewstone2018) argue that the presence of immigrant coworkers in the workplace can lead to both positive and negative contact. Greater out-group exposure indirectly increases (reduces) prejudice through greater negative (positive) intergroup contact. The authors note that contact in the workplace can be superficial, involuntary, or competitive, thus leading to more negative intergroup attitudes (see also Amir Reference Amir1969). According to Escandell and Ceobanu (Reference Escandell and Ceobanu2009), austere economic environments are likely to increase individual and group competition. Labor market competition could offset the potential benefits of meaningful workplace contact. Indeed, their analysis based on Spanish survey data finds no statistically significant association between workplace contact and foreigner exclusionism.

Summing up, according to Predictions 1 to 3, the expected net effect of increased contact between natives and non-Europeans in terms of support for anti-immigration parties is ambiguous. If workplace contact is mainly superficial, natives might fear that their economic (and social) status is threatened, which would boost anti-immigration voting behavior. If, on the other hand, the workplace facilitates contact between coworkers that is meaningful and cooperative, we expect it to reduce natives’ opposition to immigration. In such workplaces, it is important that the natives’ fear of labor market competition does not lower the tendency to collaborate or in other ways diminishes prejudice-reducing intergroup contact. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to study the relationship between intergroup contact in the workplace and support for anti-immigration parties.

Data and Empirical Design

Sample Construction and Data

The choice of situating our empirical analysis in the Swedish context is not only driven by the availability of high-quality administrative data. Several other factors make Sweden particularly suitable for this type of analysis. First, it presents a setting with a relatively high and growing share of foreign-born individuals in the workforce. At the same time, the share of votes for the largest Swedish anti-immigration party has increased substantially over the last two decades. Following the 2010 elections, which saw SD enter the national parliament for the first time, the Swedish political landscape resembles that of other Western countries, thus making the phenomenon studied in this particular case more generalizable to the contexts of other countries.

Second, compared with other Western countries, Swedish voters are among the least prejudiced (Messing and Ságvári Reference Messing and Ságvári2019). Any reduction in prejudice stemming from workplace contact would thus occur at relatively low initial levels. In addition, teleworking is more common in Sweden than in most other countries in the European Union, with a share of employed individuals working from home “regularly or at least sometimes” close to 20% in 2009 (Milasi, González-Vázquez, and Fernández-Macías Reference Milasi, González-Vázquez and Fernández-Macías2020). So, if we find that workplace contact affects support for SD in Sweden, we would expect to find similar effects in other countries with (1) a higher initial level of ethnic prejudice and (2) workplace contact entailing more in-person contact.

Election Data: Vote Shares for SD

National and local elections in Sweden take place once every fourth year, of which we use the outcomes in three consecutive (national) elections between 2006 and 2014. The reason for choosing these years is fairly straightforward: we do not yet have access to any data from the latest election (2018), thus making 2014 the most recent election for which the data are available. Before the 2006 national election, SD remained very small, receiving close to 1.5% of the votes in the 2002 national election.

Our outcome of interest is the election results for SD. Due to secret ballots, we cannot track voting for each individual voter. Instead, we use the lowest level of aggregation—namely the election precincts. There are more than 5,500 precincts in each election, and each voter is linked to a unique election precinct based on their residence. On average, each precinct comprises around 1,000 eligible voters. A number of precincts are either eliminated, altered, or merged with other precincts between two consecutive elections. To get comparable geographical units over time, we match precincts between elections using data on population density. This matching procedure leaves us with a total of 5,836 comparable precincts and is described in more detail in the online Appendix, Section B.1.Footnote 10

Using Workplace Data to Measure Workplace Contact

To construct our treatment and control variables, our analyses use detailed individual-level full population administrative data. These data are provided by Statistics Sweden and include both matched workplace and individual-level data for a rich set of socioeconomic and demographic variables. The individual-level information is used to construct aggregated measures at the election precinct level.

To create our treatment variable, we use the fact that the vast majority of working individuals are not only linked to a specific firm but also to a unique workplace. A workplace is defined as an address, property, or group of connected premises where a company operates. All firms have at least one workplace, while firms with operations in more than one address or property are divided into several workplaces. Since we wish to capture contact, a workplace is arguably more suitable than a firm, which can entail large enterprises with many workers who never encounter each other.

We connect each individual to the share of workers born outside Europe in his or her workplace.Footnote 11 We choose to focus on non-Europeans rather than immigrants in general, as we expect negative views on or prejudice against immigrants from, for example, Nordic or Western European countries to be less prevalent. Since the outcome is measured at the precinct level, we aggregate the workplace shares to this level. The treatment variable is thus created in two steps. We first define the share of non-European immigrant coworkers at workplace w for individual i living in precinct p in election year t if individual i is born in Sweden:

where Numb_Imiwt is the number of non-European coworkers and Numb_Coworkiwt is the total number of coworkers of worker i at workplace w. We use the shares for each native to create the precinct average share of non-European coworkers among natives residing in precinct p (

![]() $ i\hskip2pt \in \hskip1.5pt P $

, where P represents the set containing all natives in precinct p):

$ i\hskip2pt \in \hskip1.5pt P $

, where P represents the set containing all natives in precinct p):

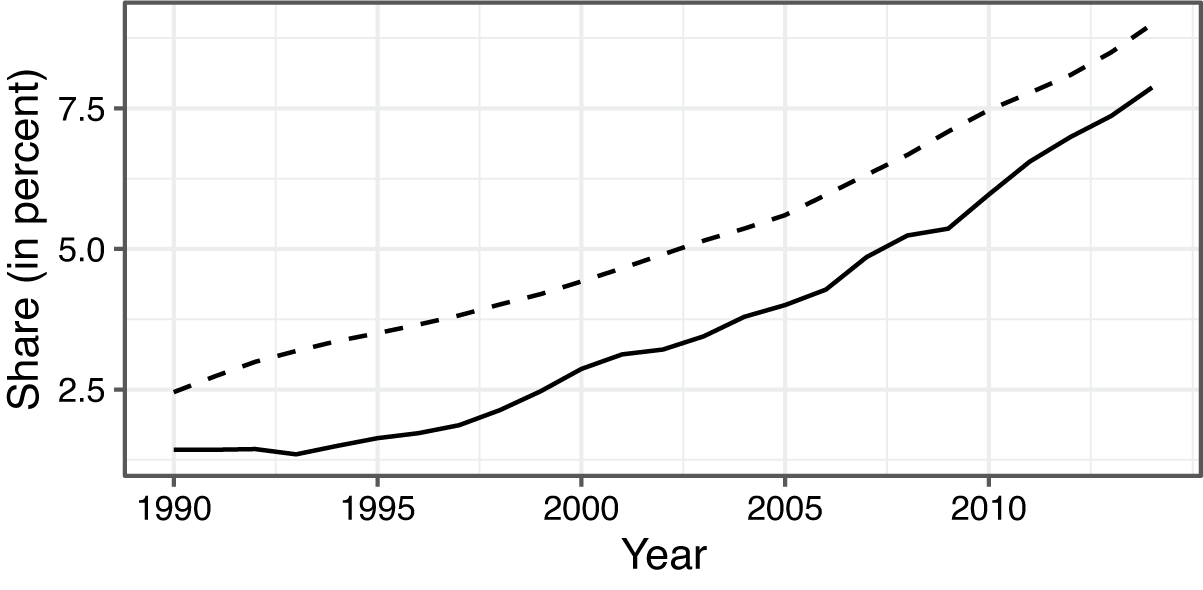

$$ Mean\_\mathit{\operatorname{Im}}\_{Share}_{pt}=\frac{1}{\mid P\mid}\sum \limits_{i\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt P}\mathit{\operatorname{Im}}\_{Share}_{iwpt}. $$

$$ Mean\_\mathit{\operatorname{Im}}\_{Share}_{pt}=\frac{1}{\mid P\mid}\sum \limits_{i\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt P}\mathit{\operatorname{Im}}\_{Share}_{iwpt}. $$

Mean_Im_Sharept, is our main treatment variable and measures the mean share of non-European coworkers for native workers residing in precinct p and election year t. It is important to note that we use information from the administrative data on where workers reside, which means that the workplace contact for each native is linked to where they vote, rather than where they work. When constructing our treatment according to Equation 2, we restrict the pool of workers by removing (a) all self-employed individuals and (b) all workers with no coworkers at their workplace. These restrictions exclude very small workplaces in which the share of non-European coworkers is not an informative indicator.Footnote 12

Constructing the precinct-level treatment comes with two important caveats. First, the individual-level share according to Equation 1 assumes a (weakly) monotonically increasing relationship between workplace contact and the share of non-European coworkers. In other words, a larger share of non-European coworkers is assumed to be indicative of more workplace contact with immigrant coworkers. As the individual-level measures of contact are aggregated at the precinct level, we are unable to capture potential nonlinearities in this relationship.

Second, the precinct-level measure of workplace contact for the average precinct resident, from Equation 2, does not use the share of non-European workplace coworkers for all natives. Self-employed individuals and those with no workplace coworkers are excluded, which means that the degree of contact with non-Europeans at work is not accounted for with respect to a large portion of the precinct (native) population. On the other hand, the election outcomes are the result of (almost) all natives’ individual-level voting actions.Footnote 13 This measurement error will induce a downward bias in our estimated treatment effect.

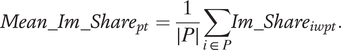

Crucially, this bias is larger when we further restrict the pool of workers to only include, for instance, same-skill coworkers. This is illustrated by Figure 1, which demonstrates how the individual-level shares of coworkers are computed. In 1a, native worker i (represented by the black figure) has a total of 13 coworkers, eight of whom are natives (white figures) and five of whom are non-European (light gray figures). Thus, native worker i’s share of non-European coworkers is 5/13, or approximately 0.38. If we instead compute the share of same-skill non-European coworkers, this share is 2/7, or close to 0.29. In the second part, Figure 1b, the high-skill native worker (black figure) has a total of seven coworkers, four of whom have a non-European background, but no same-skill coworkers. This worker is included when computing the precinct-level average for the share of non-European coworkers and excluded when we only consider the share of same-skill coworkers. Consequently, the estimates using the same-skill shares are even more likely to suffer from attenuation bias.Footnote 14 This is important to keep in mind as we interpret the magnitude of our estimates. In the online Appendix, Section B.2, we discuss these caveats further.

Figure 1. Computing the Individual-Level Share of Non-European Coworkers

Note: Example of workplaces with both same-skill and different-skill coworkers (Figure 1a) and with only same-skill coworkers (Figure 1b).

Empirical Design

We examine the relationship between the workplace presence of non-Europeans among natives and support for SD by estimating the parameters of the following linear regression model:

where SDpt gives the share of votes for SD in precinct p and election t, while Mean_Im_Sharept measures the precinct-level mean of non-European immigrant coworkers among native-born precinct residents. We add the vector

x

pt of precinct-level time-varying controls, which is based on the entire adult population in the precinct. This vector includes precinct population and population squared, mean number of days unemployed, percentage of nonworking individuals among natives, percentage of non-European immigrants living in the precinct, percentage of non-European immigrants who are citizens, and percentage of individuals with a low level of education (separately for natives and non-Europeans).Footnote

15 The same vector also includes a number of controls aggregated from the workplace level for all working residents in a precinct: average wage among coworkers, share of young coworkers, and share of male coworkers. These variables are constructed in a manner similar to our contact variable according to Equation 1 and Equation 2.Footnote

16 We include time and precinct fixed effects, represented by

![]() $ {\tau}_t $

and

$ {\tau}_t $

and

![]() $ {\Phi}_p $

, respectively. These account for national trends as well as time-invariant precinct characteristics. Our preferred specification interacts the time trends with commuting zone fixed effects to capture any specific time trend for a specific commuting zone (60 regions in Sweden). The arguably most important component is Φ

p, representing precinct fixed effects. The analysis thus compares outcomes within precincts over time.Footnote

17

$ {\Phi}_p $

, respectively. These account for national trends as well as time-invariant precinct characteristics. Our preferred specification interacts the time trends with commuting zone fixed effects to capture any specific time trend for a specific commuting zone (60 regions in Sweden). The arguably most important component is Φ

p, representing precinct fixed effects. The analysis thus compares outcomes within precincts over time.Footnote

17

Identification

For identification of β, we require that there is no unobserved variation related to votes for SD in precinct p that also confounds the share of non-European coworkers among native residents in precinct p. Our preferred specification addresses most potential threats with respect to identification. The precinct fixed effects (Φ p) capture all static differences between neighborhoods. Using only variation over time, our research setting thus asks, are the precinct-level votes for SD significantly higher or lower than the average in an election year with unusually many non-European coworkers among the precinct natives? The precinct fixed effects likely account for a large part of the omitted factors that are simultaneous with both the share of non-European coworkers and support for SD.

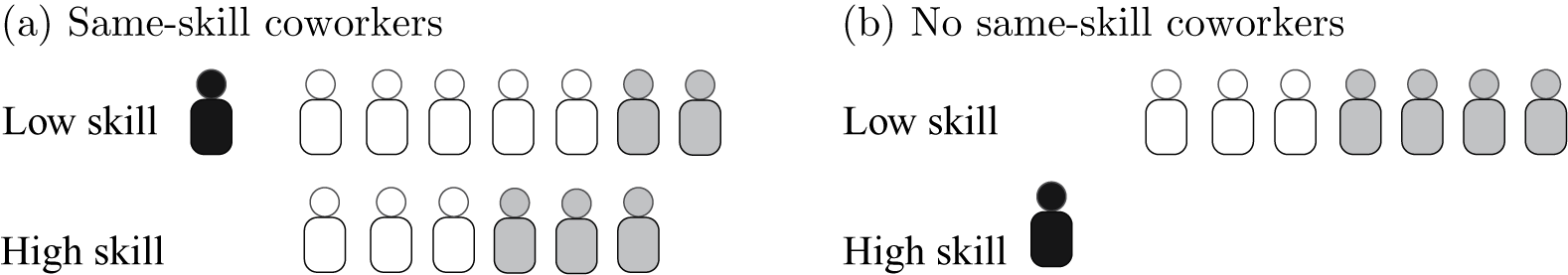

A second concern is that developments in local labor markets are related to both the political outcome of precincts located in the labor market as well as the labor market integration of migrants. Therefore, we include year fixed effects interacted with Sweden’s 60 local labor markets (commuting zones). The inclusion of these interactions captures labor-market-specific trends in terms of both workforce composition and support for SD. Both SD as a political force and immigrants in the workforce have evolved positively over the relevant period (see Figures 2 and B1).

Figure 2. Share of Non-European Individuals

Note: The dashed line shows non-European-born adults as share of total adult population, and the solid line shows averages of the share of non-Europeans in the workplace, between 1990 and 2014.

There are several confounding factors that could influence changes in terms of both support for SD and the share of non-European coworkers. For example, due to networking and simple geographical proximity, the share of non-Europeans residing in a precinct is likely to be positively correlated with the share of non-European coworkers among the neighboring natives. That is why we control for the percentage of non-European immigrants residing in each precinct. Since the effect potentially differs between subgroups of migrants, we also control for the share of low-skill non-Europeans as well as the share of non-Europeans with citizenship (with voting rights). Most individuals do not work in the same precinct as they live, which enables us to separate neighborhood exposure from workplace exposure.

The preferred specification given by Equation 3, together with local labor market time trends, addresses all of the above concerns. To be clear, the source of the variation in the intensity of workplace contact is given by changes in the composition of employees in the large number of workplaces across Sweden. So, how exactly should one think about the precinct-level variation?

The share of the Swedish population born in a foreign country has increased steadily over the past couple of decades. This has naturally also increased the share of foreign-born workers. Figure 2 depicts the share of the Swedish population born in a non-European country between 1990 and 2014 and the yearly average of the same share among workplace coworkers. Both these shares have grown over the last two decades. However, the yearly change does not remain constant across all workplaces, which means that native-born workers will to a varying degree see their workplace contact with non-European coworkers change over time.Footnote 18 Most importantly, each native’s share of non-European coworkers will vary in between elections if their workplace share changes or if they start working in another workplace.

The precinct-level treatment intensity takes advantage of changes in each native’s workplace contact, which rely on changes in workplace composition. These changes are not random: for numerous reasons, some firms, or even sectors, are more likely to employ nonnatives. In addition, changes to treatment intensity also depend on where native workers reside. Nor is this decision made by the worker random, and it will affect the precinct-level variation in the treatment. Thus, what drives the variation in the treatment are nonrandom actions of both firms and native workers. Our identification strategy relies on the assumption that these actions, conditioning on our time-varying controls and year and precinct fixed effects, are orthogonal to the potential outcomes in the support for SD.

Results

Workplace Contact and Support for SD

Our baseline estimates are presented in Table 1. The coefficients represent the effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in the average precinct-level share of non-European coworkers among working natives on the share of votes for SD. Column 1 includes the main treatment variable, time and precinct fixed effects, and time-varying precinct-level controls to account for precinct-specific time trends in a set of key factors, most importantly the share of resident non-Europeans. In column 2, we add an interaction term between the time and labor market region dummies, which accounts for labor market-specific time trends, whereas column 3 adds a set of workplace-specific controls.

Table 1. Share of Non-European Coworkers and Support for SD

Note: ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at 0.1%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively, based on clustered standard errors (at precinct level).

The estimated effect of the share of non-European coworkers among natives on the share of votes for SD drops significantly as we control for local labor market trends (compare columns 1 and 2). As workplace controls are added, the estimated slope coefficient instead turns more negative (column 3). The third column represents our most conservative and most preferred specification. The estimated slope coefficient suggests that a one-standard-deviation increase in the share of coworkers (approximately a 3-percentage-point increase) is associated with a decrease of 0.428 percentage points in votes for SD. This decrease represents around 8% of a standard deviation in the dependent variable, or around 12% of a standard deviation in the change in votes for SD. In our sample, a standard deviation in the precinct votes for SD is 5.8%, and a standard deviation in the change in votes for SD is equivalent to 3.4 percentage points.Footnote 19

The negative effects in Table 1 (columns 1–3) are in line with the contact hypothesis: meaningful contact with members of ethnic minority groups reduces opposition to immigration and, subsequently, voting for anti-immigration parties. At the very least, any increase in anti-immigration voting stemming from more contact with non-Europeans seems to be offset by the decrease resulting from meaningful contact. However, Prediction 1.1 suggests that the presence of same-skill foreign-born coworkers captures the threat of increased labor market competition between natives and foreign-born workers more than the overall presence. For example, high-skill natives would not expect to compete for employment and high wages with low-skill immigrants, as these two groups essentially compete in different labor markets. At the same time, we expect coworkers with the same skill level to have even more meaningful workplace contact, as they are most likely involved in similar tasks. To shed light on the importance of same-skill non-European coworkers in the context of workplace contact, we divide the pool of workers into two groups: one for high-skill workers and one for low-skill workers based on occupation categories.Footnote 20

In the following case, an arbitrary native’s share of non-European coworkers is computed by only using coworkers of the same skill level as that native. These individual-level shares are then aggregated to the precinct level. For completeness, we also create a measure for the share of non-European coworkers in the different skill cell. As we can see in the last column in Table 1, a negative coefficient is estimated only for same-skill workplace contact. Compared with the estimated slope coefficient of our preferred specification (column 3), the estimate for same-skill contact is slightly less negative but qualitatively the same.Footnote 21 In terms of contact with different-skill coworkers, the estimated slope coefficient is not distinguishable from zero.

This illustrates that the negative effect of workplace contact on voting for SD is solely driven by same-skill contact, which does not fit well with the competition hypothesis. Instead, it offers support for the predictions in line with the contact hypothesis. Social networks tend to be stratified depending on social status and class, and a stylized fact in many workplaces is the lack of vertical integration. We thus expect colleagues to engage more frequently and in similar tasks at the same skill level, which explains the negative effects in the same-skill estimation. The lack of vertical integration could also explain the absence of any effect of different-skill contact on the share of votes for SD. Coworkers with different skills are less likely to engage repeatedly in cooperative interactions and do not tend to share the same or similar backgrounds and social status.

Robustness Checks and Placebo Tests

We validate our main effects by conducting a number of robustness checks. The results from these robustness checks can be found in the online Appendix, Section C. First, we test the sensitivity of our analysis by excluding potential outliers. We identify outliers by considering observations with (a) unusually large or small precinct populations (or population growth), (b) unusually large or small regression residuals, and (c) high leverage points. Our main findings are robust to all these alterations (see Tables C1–C4).

Second, in a series of placebo tests, we regress different, ex ante unrelated outcomes on the precinct-level treatment variable. Most importantly, we regress lagged election outcomes for SD on future levels of workplace contact. This yields no statistically significant association. Nor does including the same lagged dependent variable on the right-hand side in the main specifications alter the results (Tables C5 and C6). In addition to the lagged dependent variable, we use vote shares for other nonmainstream parties, the share of blank ballots, and the share of newly married and newly divorced precinct residents. These placebo tests yield statistically insignificant estimates.

Third, we make alterations to the treatment variable. We replace the treatment with the average number of workplace coworkers among native residents regardless of coworker origin. We also assign a randomly drawn workplace share—from the actual workplace data—to each native worker 1,000 times and reestimate the model using aggregated data based on each randomization. These tests yield statistically insignificant estimates. In addition, we show that the results are robust to using a treatment computed from non-European coworkers as deviations from industry-level averages (Table C7 and Figure C2).

Fourth, we address selection into treatment. We use a large Swedish survey from 2009 to show that natives with preferences for restrictive immigration policies were not more likely to reside in or move to precincts experiencing a smaller future increase in the average share of non-European coworkers (Figure C3). We also show that our main results are robust to only focusing on natives who did not change precinct residence over two consecutive elections (Table C7). These results lend further support to our identification strategy, as it suggests that voters did not select into precincts based on their opposition to immigration.

Finally, the treatment variable in Table 1 only includes workplaces with at least one workplace coworker and excludes all self-employed individuals. In Table C9, we drop these restrictions and show that the results are virtually the same. Having shown that the estimated negative effect of increased workplace diversity on support for anti-immigration parties is robust to various specifications and also that these results are likely not driven by selection or unobservable trends, we next explore whether the estimated effect can be attributed to workplace contact.

Mechanism

While our data contain many strong features, a clear drawback is that we do not know to what extent individuals actually engage with each other in the workplace. Our interpretation of the results presented in the previous section hinges on the assumption that cooperative and meaningful contact actually occurs between natives and their coworkers of non-European origin. The mechanism we propose is that of contact—either meaningful or superficial—between natives and immigrants and that this explains how the share of non-European coworkers affects support for SD. This section provides suggestive evidence in line with the proposed mechanism.

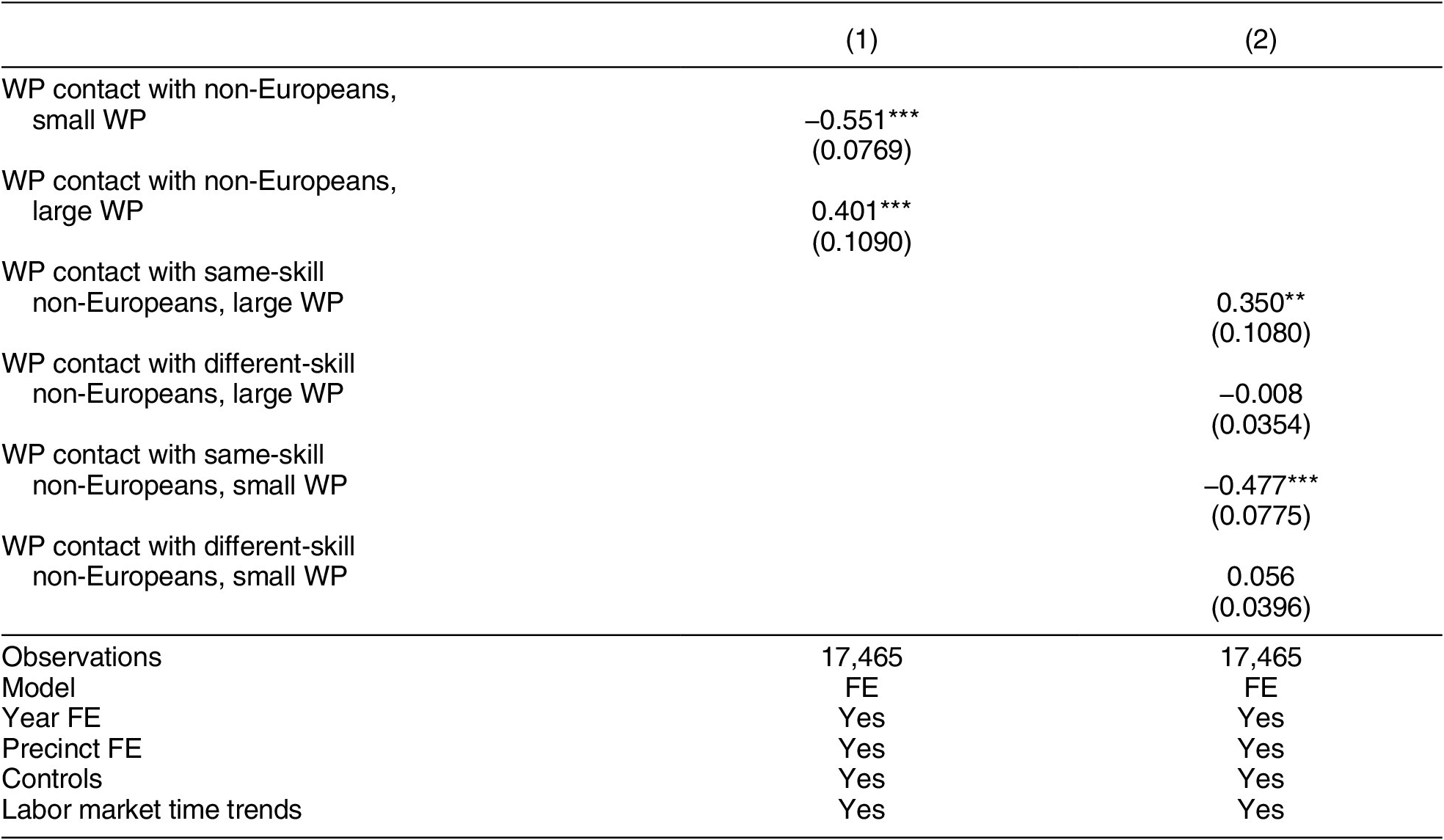

To better identify actual contact between work peers, we can stratify the pool of workers in at least two ways. First, we can divide the workers into categories we deem more likely to engage with each other, which we did when only considering same-skill coworkers (Table 1, column 4). Second, we can perform the analysis for different sets of workplaces. One obvious division in terms of expected contact between coworkers is the size of the workplace. A plausible scenario is that meaningful contact is more likely to occur at small workplaces, as the probability of repeated interactions with the same coworkers is lower in large settings with more coworkers. In large workplaces, contact between coworkers is more likely superficial or casual in nature. As a result, we categorize all workplaces as either large or small by using the number of employees.Footnote 22 Small (large) workplaces are defined as having less (more) than the median number of employees, which was 57 in 2006. The average share of non-European coworkers at the precinct level is then computed exactly as before, with the key difference that we construct separate precinct-level measures for the average native workers employed at small or large workplaces, respectively.

The results in the first column of Table 2 use information from both large and small workplaces. As we can see, the negative effect is exclusively driven by contact at small workplaces, which corresponds well with our notion of contact being the key mechanism. On the other end, the effect for large workplaces is positive, which we return to below.Footnote 23

Table 2. Small versus Large Workplaces

Note: ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at 0.1%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively, based on clustered standard errors (at precinct level).

Note that even in smaller workplaces, it is not certain to what degree individuals with different work-related tasks actually engage with each other. In what follows, we further decompose the subgroups and estimate the effect of four different levels of contact—namely same-skill or different-skill level at small or large workplaces. Because our expectation is that meaningful contact is the key mechanism, we would expect a larger coefficient (i.e., more negative) for same-skill level workplace contact with non-Europeans in small workplaces due to the higher likelihood of repeated interactions. At the same time, we expect that the fear of labor market competition can impede prejudice-reducing intergroup contact by, for instance, decreasing natives’ will to collaborate. This offsetting mechanism is plausibly less likely for the context of same-skill workers at smaller workplaces, where the limited number of same-skill workers makes it more difficult to “opt out” of collaborations.

The estimates are presented in Table 2, column 2, and offer several take-aways. First, note that both slope coefficients based on different-skill variation, regardless of workplace size, render small and statistically insignificant point estimates. This is identical to the baseline results in Table 1, column 4. Second, as hypothesized, the point estimate using the share of same-skill level workplace contact with non-Europeans at small workplaces is negative and qualitatively similar to the point estimate for small workplaces in column 1.Footnote 24 This is again in line with the contact hypothesis: meaningful contact with same-skill non-European coworkers at small workplaces reduces support for anti-immigration parties.

Furthermore, the positive effect for large workplaces in column 1 is almost exclusively driven by same-skill contact. Any potential reduction in opposition to immigration from workplace contact with non-Europeans at these workplaces seems to be offset by mechanisms going in the opposite direction; for example, fear of increased (same-skill) labor market competition. We believe that the most plausible explanation for the diverging results between small and large workplaces can be attributed to the actual size of these workplaces. The much larger pool of same-skill coworkers at large workplaces means that it is less likely that a native shares tasks and has repetitive and cooperative contact with any given same-skill non-European coworker. The large number of workers also increases the possibility to select out of collaborations with certain segments of the workforce. These coworkers will, however, still be visible in the workplace and potentially be regarded as a threat to natives’ high wages and employment opportunities. In the absence of meaningful contact, the presence of same-skill non-European coworkers will thus strengthen opposition to immigration in accordance with the ethnic competition hypothesis.

The conclusions from the point estimates in Table 2 are summarized in Table 3. The lack of vertical integration in many workplaces, both small and large, limits the amount of contact taking place between workers with different skill levels. At the same time, workers with a particular skill are not expected to compete with immigrant workers with a different skill. This explains the precisely estimated zero effects of workplace contact with different-skill non-Europeans at both small and large workplaces. On the contrary, the divergent results for same-skill contact can be explained by differences in the type of contact most likely to occur in small and large workplaces, respectively. Only meaningful contact will offset the positive effect of the presence of a labor market threat on opposition to immigration.

Table 3. Meaningful Intergroup Contact and Labor Market Threat

Note: Types of contact and degrees of labor market threat for different combinations of workplace size and skill level.

Extension: Is Meaningful Contact Less Common in Vulnerable Occupations?

We have so far assumed that the threat of competition is merely “highlighted” when natives are exposed to immigrants in the workplace. A natural question is whether actual labor market vulnerability dampens the overall negative effect of meaningful workplace contact on opposition to immigration as specified in Prediction 3.Footnote 25 To examine this possibility, we consider the effect of workplace contact among natives employed in vulnerable occupations.

The labor economics literature notes that technological developments have led to an increasing job loss in occupations with a higher degree of routine-based tasks (Autor, Levy, and Murnane Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003; Goos, Manning, and Salomons Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014). The logic behind this development, somewhat simplified, is that jobs with a high degree of repetitive tasks are easily codifiable and computerized, implying that tasks previously performed by humans can now be performed by computers or robots. The opposite is true for occupations involving more abstract, problem-solving tasks.

To measure workplace vulnerability, we use two-digit International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) codes, effectively categorizing individuals into 27 different occupations.Footnote 26 We then separate the precinct-level averages of the share of non-European coworkers into vulnerable and nonvulnerable occupations using the Routine Task Intensity (RTI) index in Goos, Manning, and Salomons (Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014), The RTI index classifies the 27 two-digit ISCO occupation codes with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, which gives a scale from office clerks at 2.26 to the, supposedly, safe role of manager at -1.52. To deconstruct even further for our purposes, we consider the top quartile of the index to be vulnerable occupations and the bottom quartile of the index to be nonvulnerable occupations. In the interest of not losing too much information when computing the precinct-level average shares, we use our baseline measure as treatment (i.e., the overall share of non-European coworkers for natives).

The effect of non-European coworkers is estimated separately for the two categories of vulnerability, and the results are presented in Table 4. As shown in column 1, there is a small positive effect of workplace contact on support for SD for natives in the most vulnerable occupations, statistically significant at the 5% level. At the other end, the effect of workplace contact remains negative and statistically significant for natives employed in nonvulnerable occupations (column 2). The estimate is smaller than the baseline case and can most likely be attributed to attenuation bias due to the restricted number of natives included when computing the precinct-level averages.

Table 4. Vulnerable versus Nonvulnerable Occupations

Note: ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at 0.1%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively, based on clustered standard errors (at precinct level).

An important limitation is that the pool of native workers used for computing the share of non-European coworkers in vulnerable occupations consists of natives who, despite the relatively higher risk of job loss, were still employed. The characteristics among those who did not lose their jobs might differ from those who were laid off. Thus, we have a potential selection problem that would bias our estimates. The direction of the bias is not obvious, as we do not know how those who stayed differ from those who left. Therefore, we should interpret these results with caution.

With this caveat in mind, how should we approach the results in Table 4? One possible story is that contact between colleagues is more prevalent among nonvulnerable occupations. While this would fit very well with our suggested mechanism, we remain skeptical of this interpretation. It is not certain that physical professionals or drivers and mobile plant operators (low vulnerability) have more day-to-day contact with colleagues than office clerks (high vulnerability). Instead, our preferred interpretation is in line with Allport’s condition regarding “basic security” (Prediction 3): an increased presence of immigrants is less likely to result in meaningful contact if natives feel that they are at risk of losing their jobs.Footnote 27 In other words, natives might care more about labor market competition from immigrants if they indeed face a high risk of losing their jobs. In such a setting, workplace contact could instead increase opposition to immigration, which is in line with the ethnic competition hypothesis.

Note that this does not require natives blaming immigrants for their vulnerable labor market position. Instead, a higher share of immigrant coworkers can increase opposition to immigration among natives in vulnerable occupations if they expect to have to compete with immigrants for the remainder of the available jobs in their sector or occupation. The mere presence of immigrants in the workplace could highlight the threat of increased competition for employment.

Conclusion

In this paper, we use Swedish full population data to present evidence of an overall increased share of non-European coworkers in natives’ workplaces having a negative influence on support for anti-immigration party the Sweden Democrats. We examine the consequences of intergroup contact in different workplace environments and arrive at the following conclusions. First, we interpret the negative effect of an overall increased share of non-European coworkers as support for the contact hypothesis—namely, that the increased presence of immigrants (in this case at work) makes natives less inclined to vote for an anti-immigration party. To support this interpretation, we stratify results along skill levels. Workplaces often have low vertical integration, and social interactions—both positive and negative—primarily occur within the same skill level. Thus, we only expect the presence of non-Europeans within the same skill cell to influence opposition to immigration. Our results show that negative effects on votes for SD arise solely from an increase of non-European coworkers with the same skill level.

Second, when categorizing workplaces as either small or large based on the number of employees, we find that only same-skill workplace contact with non-Europeans at small workplaces has a negative influence on SD votes. While native workers with a particular skill are expected to lose from the immigration of people with the same skill, we do not find support for same-skill contact causing a rise in support for SD in small workplaces. On the other hand, same-skill contact in large workplaces leads to greater support for SD. These results suggest that in settings facilitating intimate and repetitive contact (small workplaces), the potential increase in opposition to immigration from exposure to immigrant coworkers is, on average, offset by meaningful contact. Conversely, when contact is less repetitive, same-skill immigrant coworkers are likely to exhibit increased opposition to immigration.

Third, we present suggestive evidence of different estimated effects of workplace contact for vulnerable and nonvulnerable occupations, where a negative effect on support for SD only appears for nonvulnerable occupations. The opposite is true for vulnerable occupations. A possible interpretation of these results is that labor market competition from immigrants becomes more pressing for natives when there is a greater risk of job loss, thus offsetting the potential benefits of meaningful contact. However, one should be careful when interpreting these estimates because they potentially suffer from selection bias.

The results add new evidence to the expanding literature on the rise of anti-immigration and radical right parties. The main part of this literature, which considers neighborhood contact, finds a positive association between the share of immigrants and voting for anti-immigration parties. Our focus on the workplace suggests that the opposite relationship exists. Our empirical design, which relies on precinct-level election results for three consecutive Swedish national elections as well as a measure of the average share of non-European workplace coworkers among native residents, allows us to study the effect of workplace contact on support for SD. There are limitations to this approach. First, the precinct-level average shares do not allow us to capture any nonlinear effects of workplace contact on SD votes. The consequences of additional workplace exposure to immigrants might depend on the initial level, and the intensity of contact is not necessarily linear in the share of immigrant coworkers. Second, the aggregate-level data give us limited possibilities for studying the channels through which workplace contact translates into party preferences. These issues could instead be addressed using detailed survey data. Students of intergroup contact should direct more attention to designing surveys, enabling us to learn more about channels and potential nonlinearities.

The choice to situate our empirical analysis in the Swedish context involves both advantages and disadvantages. Besides the advantage of having access to high-quality administrative and election data, Sweden constitutes a least-likely case with its high share of employees working from home and low overall level of prejudice. While the former suggests a stronger negative association between the share of immigrant coworkers and opposition to immigration in countries with a higher degree of on-site working, the latter condition could potentially limit generalizability: individuals in countries with a higher overall level of prejudice are potentially more likely to be predisposed to negative or superficial contact with immigrant coworkers (see Laurence, Schmid, and Hewstone Reference Laurence, Schmid and Hewstone2018). In these contexts, workplace contact could have different consequences in terms of support for anti-immigration parties.

It is also important to note that another distinct aspect of the Swedish context is the low level of sociability between neighbors. As noted by Daun (Reference Daun1991), Swedes are in general reluctant to engage with their neighbors, and contact between neighbors is not a socially sanctioned norm (Goldschmidt, Hällsten, and Rydgren Reference Goldschmidt, Hällsten and Rydgren2017). This has potential consequences for the likelihood of friendship between coworkers. In countries with a stronger norm of sociability between neighbors, workplace-based friendships are perhaps less likely to arise. Given these limitations, we propose that future research takes into account both the initial level of prejudice and the likelihood of contact in other contexts.

Another important avenue for future research relates to the increasing tendency to work from home. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, interactions between coworkers have changed at many workplaces: while virtual meetings allow workers to connect with each other from home, physical meetings and interactions at the water cooler arguably entail more intimate contact. Is the decline of on-site working related to the rise of the radical right?

The results in this paper on job security and workplace contact should be interpreted with caution, as the data employed are likely less suited for this type of analysis. Another way of examining the relevance of job security—both actual and perceived—is by using detailed survey data on respondents’ share of immigrant coworkers, as well as their perceived unemployment risk and stated policy preferences. By matching the survey respondents to administrative data on socioeconomic characteristics and workplace information, one could analyze the influence of the actual presence of immigrant coworkers for different levels of job security. This could greatly enhance our understanding of how economic distress influences the relationship between workplace contact and opposition to immigration.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000599.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation is openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0WIFZU. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the Online appendix.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Political Economy Workshop in Bologna, the first PII scientific workshop at LSE, 2nd CReAM/RWI Workshop in Essen, the Workshop on Populism and the Rise of the Radical Right at Uppsala University, the 2019 Workshop on Political Economy at the University of Barcelona, and research seminar at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics and the Institute for Housing and Urban Research (Uppsala University). We thank the editors, three anonymous reviewers, Linuz Aggeborn, Anders Björklund, Carl Dahlström, Matteo Gamalerio, Nazita Lajevardi, Pär Nyman, Sven Oskarsson, Torsten Persson, Charlotta Stern, Per Strömblad, Susanne Urban, and Sarah Valdez for helpful comments and suggestions.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the European Research Council (grant number 683214), the PII-project in the NORFACE DIAL program, and the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.