INTRODUCTION

Nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe saw unprecedented economic, political, and cultural change. Industrializing economies, expanding markets, centralizing states, and nationalist ideologies fundamentally transformed both private and public life (Ansell and Lindvall Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021; Buzan and Lawson Reference Buzan and Lawson2017; Osterhammel Reference Osterhammel2014). New transport technologies, especially railways, drove these modernizing forces (Maier Reference Maier2016). Railroads connected previously isolated subnational regions, fostered industrialization, and boosted the state’s ability to reach and govern peripheral populations. As such, they helped to create the communicative, economic, and political conditions that promoted national integration and identity formation (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1953; Gellner Reference Gellner1983). Simultaneously, expanding transportation networks contributed to separatist mobilization of culturally distinct peripheral groups (Breuilly Reference Breuilly1982; Hechter Reference Hechter2000; Huntington Reference Huntington1968).

In this paper, we investigate how the expanding European railway network contributed to nationalist mobilization that either united or divided states. Our theoretical argument builds on and extends the existing literature on modernization, nationalism, and separatism. We specify three mechanisms through which railroads may affect competition and bargaining between the central state and ethnically distinct peripheral regions. While improved access to national markets and the capital city can be expected to promote integration and stability, internal connections in the periphery are likely to fuel local mobilization and separatism. Since the integrative processes of cultural assimilation, state-led nation building, and economic modernization tend to unfold more slowly than local resistance, we expect the first arrival of rails in ethnic minority regions to increase the risk of separatist mobilization. The impact of more gradual extensions of the network is likely to depend on how they affect national market access, state reach, and local mobilization capacity. In addition, we study how ethnic demography, economic development, and political institutions affect whether railroad construction caused national integration or disintegration.

We test these arguments by combining newly collected geo-spatial data on the expanding European railway network (1834–1922) with measures of independence claims, secessionist civil wars, and successful secession (1816–1945). We link these data to yearly observations of ethnolinguistic group segments derived by intersecting historical maps of ethnic settlements with time-varying country borders covering the period 1816–1945.

First, we find that, on average, railway access is associated with an about twofold increase in the probability of separatist mobilization. This effect materializes immediately and dissipates over time without turning negative. In addition to observing parallel pretreatment trends, an instrumental variable approach based on simulated railroad networks bolsters the robustness and causal interpretation of our findings. Second, our analysis of heterogeneous effects shows that separatist responses to railway access complicate top-down nation building in states with low levels of economic development and state capacity while providing motivations and opportunities for national independence campaigns, in particular among large minorities. Third, a disaggregated analysis of mechanisms underlying the effect of railway access suggests that improvements in state reach reduce separatism, internal connectivity increases the risk, and that market access exerts little effect.

Our paper contributes to the literatures on modernization, nationalism, separatism, and the political consequences of transport and communication technologies. Analyzing railroad construction and other dimensions of modernization, historians provide convincing qualitative evidence on national integration in France (Weber Reference Weber1976) and disintegration and separatist nationalism in Eastern Europe (Breuilly Reference Breuilly1982; Connelly Reference Connelly2020). In economic history and geography, there is a rich literature on the impact of railway construction on economic development, urbanization, and industrialization (see, e.g., Alvarez-Palau, Díez-Minguela, and Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021; Berger Reference Berger2019; Donaldson Reference Donaldson2018; Donaldson and Hornbeck Reference Donaldson and Hornbeck2016; Fishlow Reference Fishlow1965; Hornung Reference Hornung2015), but less is known about how it influences political outcomes, such as nation building. In a study of nineteenth century Sweden, Cermeño, Enflo, and Lindvall (Reference Cermeño, Enflo and Lindvall2022) show how railways empower public school inspections, leading to higher enrollment rates and more nationalist curricula in connected locations. Yet recent empirical contributions link railroads to the diffusion of opposition movements (Brooke and Ketchley Reference Brooke and Ketchley2018; García-Jimeno, Iglesias, and Yildirim Reference García-Jimeno, Iglesias and Yildirim2022; Melander Reference Melander2021) and resistance to the state (Pruett Reference Pruett2024).Footnote 1

What is missing, however, are studies that analyze both integrative and disintegrative dynamics systematically and more broadly. Our arguments and findings provide a comprehensive assessment of how a crucial technological driver of modernization relates to separatist mobilization across Europe.

MODERNIZATION AND NATIONALISM IN THE LITERATURE

The introduction of steam-powered railroads is often described as “the defining innovation of the First Industrial Revolution” (Cermeño, Enflo, and Lindvall Reference Cermeño, Enflo and Lindvall2022, 715) and is thus inextricably linked with the various modernization processes that spread across Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A large, and by now classic, literature links the rise of nationalism to these processes (see, e.g., Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1953; Gellner Reference Gellner1983). The relevant arguments fall into two main camps depending on whether they stress national integration or separatism.

The former school expects cultural homogenization and increasing identification with the state-leading nation (see, e.g., Eifert, Miguel, and Posner Reference Eifert, Miguel and Posner2010; Robinson Reference Robinson2014). Political accounts highlight the modern state as the key agent of change (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1990). On this view, states devise and implement nation-building programs to respond to both international and domestic threats (Hintze Reference Hintze and Gilbert1975; Posen Reference Posen1993; Tilly Reference Tilly1994). A complementary perspective views the development of industrial economies as the main integrating force. In Gellner’s (Reference Gellner1983) seminal account, the transition from agrarian to industrial modes of production requires standardized languages (see also Gellner Reference Gellner1964; Green Reference Green2022). In a pioneering book, Deutsch (Reference Deutsch1953) highlights expanding communication networks resulting from technological innovation, labor migration, and market exchange as industrial drivers of nationalism.

Despite their integrationist thrust, modernist accounts also shed light on national disintegration. Adopting a political perspective, Breuilly (Reference Breuilly1982) and Hechter (Reference Hechter2000) expect the shift from indirect to direct rule to trigger reactive mobilization, especially where peripheral elites enjoyed autonomy prior to state centralization. Similarly, Deutsch (Reference Deutsch1953) notes that wherever social mobilization outpaced assimilation, nationalist conflict became more likely (see also Cederman Reference Cederman1997, chap. 7). Gellner (Reference Gellner1983; Reference Gellner1964) expects the combination of pre-existing cultural difference and uneven development to trigger separatism.

Complementing the theoretical classics, several empirical studies analyze, albeit selectively, the link between modernization and nationalist mobilization. Perhaps most famously, Eugen Weber (Reference Weber1976) traces French national identity formation in the 19th century, highlighting industrialization, expanding transportation and communication networks, and state policies as integrating forces. Despite his brilliance, however, Weber (Reference Weber1976) remains a historian of France, a country that enjoyed particularly successful nation building compared to most other European countries.

More recently, cross-country studies show that state-led nation-building efforts, in particular education reforms, become more likely when rulers faced international (Aghion et al. Reference Aghion, Jaravel, Persson and Rouzet2019) or domestic threats (Alesina, Giuliano, and Reich Reference Alesina, Giuliano and Reich2021; Paglayan Reference Paglayan2022). While these studies explain the strategic timing of nation-building policies, the mere adoption of such efforts does not guarantee their success.

Micro-level quantitative work within single countries illustrates how specific educational, linguistic, and religious state building efforts succeeded or backfired in 19th century and contemporary France (Abdelgadir and Fouka Reference Abdelgadir and Fouka2020; Balcells Reference Balcells2013), Prussia (Cinnirella and Schueler Reference Cinnirella and Schueler2018), colonial Mexico (Garfias and Sellars Reference Garfias and Sellars2021), early twentieth century US (Fouka Reference Fouka2020), and Atatürk’s Turkey (Assouad Reference Assouad2020). These contributions provide important evidence on how specific state policies cause national integration or disintegration but say less about cross-country variation.

In one of the very few comparative studies, Wimmer and Feinstein (Reference Wimmer and Feinstein2010) focus on nation-state creation in a global sample of 145 territories corresponding to independent states in 2001 back-projected until 1816. Using railway density as a modernization proxy, they find no effect on the transition to nation-states in pre-national or newly independent states. Despite this pioneering effort, their over-aggregated research design suffers from hindsight bias due to the backward-projected sampling based on contemporary state units which were shaped along ethnic lines as a result of nationalist border change (Cederman, Girardin, and Müller-Crepon Reference Cederman, Girardin and Müller-Crepon2023; Müller-Crepon, Schvitz, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Schvitz and Cederman2025).

In sum, then, the link between modernization and national integration and disintegration remains contested. First, scholars disagree about whether modernization spurs nationalism for or against the state and what mechanisms account for the link between modernization processes and nationalist mobilization. Second, the existing literature provides little theoretical or empirical guidance as regards the contextual factors that produce state building or counter-state nationalism in specific cases. Third, while the classic contributions offer little systematic evidence for their claims, the recent micro-level studies convincingly validate parts of the classical theories in selected countries, but offer no comparative outlook.

The present paper addresses these three gaps in the existing literature. First, we analyze railway construction to assess whether this crucial technological driver of modernization has systematically produced national integration or disintegration. Second, we study causal mechanisms and contextual factors that contribute to national integration or counter-state nationalism. Third, our Europe-wide data are spatially disaggregated at the subnational level, thus allowing us to integrate the literatures relying on cross-country comparisons and micro-level analysis of individual cases.

RAILWAYS AND NATIONALIST MOBILIZATION

As our discussion of existing research shows, railway expansion and the associated modernization processes likely affected European nationalisms through multiple mechanisms and with ambiguous implications for national cohesion and political stability within given state borders. The integrative potential of expanding state presence and the exchange of goods, people, and ideas over large distances point to successful nation building. At the same time, local connectivity and modernization may facilitate oppositional mobilization and spur separatist responses to national integration.

Our theoretical framework draws on the literature reviewed above to explain how, and under what conditions, railroad construction united or divided Europe’s multi-ethnic states. We introduce mechanisms through which railways affect the motivations and opportunities for separatist mobilization among non-dominant population groups. These groups are culturally distinct from their host state’s governing elites, typically demographically smaller, and more peripherally located than their state-leading counterparts (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012). Practically all states in Europe contained such minority segments. Before industrialization, central governments typically ruled non-dominant groups indirectly by outsourcing important governing tasks to local intermediaries (Hechter Reference Hechter2000). Cultural difference and mediated forms of projecting power suggest that most European states still operated more like empires (Burbank and Cooper Reference Burbank and Cooper2010; Motyl Reference Motyl and Barkey1997).Footnote 2

The situation changed when industrialization, direct forms of rule, and nationalist ideologies swept across Europe in the nineteenth century. Separatist mobilization occurred wherever elites of non-dominant groups managed to rally their followers against the state. Benefiting from agrarian economies and indirect rule, some leaders belonged to old elites, whose status was threatened by local industrialization or state centralization (Garfias and Sellars Reference Garfias and Sellars2021; Hechter Reference Hechter2000). Other leaders made up “new elites”, ranging from bourgeois liberals and democratic reformers to ethnonationalists (Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1987).

For these new and old elites, separatism provided several advantages over alternative forms of mobilization. First, national independence would assure exclusive access to the benefits of local governance which were increasingly endangered by central state expansion (Hechter Reference Hechter2000). Second, stressing cultural unity at the local or regional level helped to forge coalitions between old agrarian elites and rising middle classes whose economic interests were typically unaligned (Breuilly Reference Breuilly1982). Third, once ideologies of national self-rule took root, bravely resisting domination by a culturally foreign elite allowed elites to mobilize local populations more effectively than alternative opposition frames (Balcells, Daniels, and Kuo Reference Balcells, Daniels and Kuo2023; Gellner Reference Gellner1983). Lastly, separatist mobilization raised the prospects of securing support from nationalizing great powers, which became increasingly receptive to ideals of national self-determination (Breuilly Reference Breuilly1982).

Taking separatism as the main outcome under investigation circumvents the challenge of defining and measuring national integration at subnational levels. National integration can be achieved through assimilation into the national dominant group, the development of an overarching identity on top of ethnic diversity, or political integration and power sharing across ethnic divides (Rohner and Zhuravskaya Reference Rohner and Zhuravskaya2023; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018). Given these different paths to national cohesion, it seems analytically more productive to focus on whether crucial, necessary conditions for integration are absent or, in other words, zoom in on clear failures of nation building. Wherever a culturally distinct region breaks away from a state or mobilizes the local population in an attempt to do so, nation building has evidently failed.Footnote 3

Among the forms that separatist mobilization can take, we consider the formation of organizations claiming autonomy or independence for an ethnic group, as well as attempted or successful secessions. While some separatist movements never went beyond making nationalist claims, such as the demands for autonomy by Spanish Galicians in the 1930s (Garcia-Alvarez Reference Garcia-Alvarez1998), other movements escalated violently. In the Ottoman Empire, for instance, Bulgarians and Romanians successfully gained independence through the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. In both cases, initial independence claims were followed by secessionist civil war in the 1870s (Goina Reference Goina2005, 137; Minahan Reference Minahan2001).

Motivations Driving Railroad Construction

Before discussing the consequences of railroads in Europe, we provide a brief overview of the motivations behind their construction. In Britain, commercial actors took the pioneering steps toward connecting urban centers (Bogart Reference Bogart2009; Trew Reference Trew2020). The British case, however, is unrepresentative in this respect. France saw a more active governmental role in railway planning, which served to promote not only economic development but also national integration and cultural penetration into the country’s periphery (Weber Reference Weber1976). The centralizing logic was also present in Sweden (Cermeño, Enflo, and Lindvall Reference Cermeño, Enflo and Lindvall2022), Belgium, and with major delay, Spain (Alvarez-Palau, Díez-Minguela, and Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021). In unifying Germany and Italy, railroad construction contributed to integrating previously independent entities, although with considerable lack of efficiency in the latter case (Schram Reference Schram1997). French planners were also motivated by geo-strategic considerations, especially the need to counter Prussian/German rail-based mobilization (e.g., Alvarez-Palau, Díez-Minguela, and Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021, 264).

Further east, the large multi-ethnic empires were more reluctant to engage in nation building. Their dynastic elites saw nationalism primarily as a threat rather than as an asset. Besides limited access to capital, this reluctance delayed the introduction of railways and their use for the purpose of nation building. Nonetheless, the military threat posed by the western great powers increased the pressure on imperial decision making, both in the Habsburg Empire and tsarist Russia (Gutkas and Bruckmüller Reference Gutkas and Bruckmüller1989). While commercial interests had driven early railroad construction in the former empire, concerns with securing its borders and quickly deploying its troops motivated Vienna’s extension of railroad lines to the Russian border and into the Italian peninsula (Köster Reference Köster1999; Rieber Reference Rieber2014).

With even less access to private finance, the Romanov Empire similarly used railways to reinforce its external borders, but also as a tool of imperial rule (Schenk Reference Schenk, Lonard and von Hirschhausen2011). In 1863, the newly built rail connection between St. Petersburg and Warsaw allowed the tsarist regime to send troops that crushed the Polish revolt. Yet the belated drive for nation building and Russification gave railroads a prominent role as cultural homogenizers. As these different motivations of railroad construction may potentially be related to past or future separatism, the empirical analyses below include different strategies that account for endogenous railroad expansion.

Railroads, Modernization, and Separatist Mobilization

We now turn to our main arguments of how railroad construction may affect the choice of non-dominant populations to support separatist movements. This choice depends on the expected costs, benefits, and chances for success of state-led nation building and national independence campaigns. Railway construction in the periphery may thus affect the emergence of separatist movements if it shifts these costs, benefits, and success probabilities as perceived by local populations. Here we describe three broad mechanisms through which access to expanding railway networks matters and derive our baseline hypothesis. Next, we link our causal mechanisms to specific forms of more gradual railway expansion before deriving contextual factors that may tilt the balance in favor of integration or disintegration.

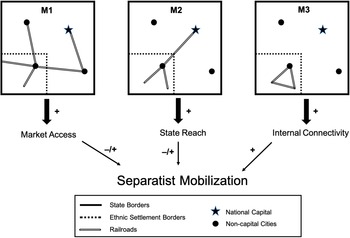

The three theoretical mechanisms through which railroads may have affected non-dominant individuals in modernizing Europe are illustrated in Figure 1 and relate, respectively, to increased interactions between dominant and non-dominant (M1), the state’s ability to reach and penetrate non-dominant populations (M2), and non-dominant elites’ and populations’ capacity to mobilize against the state (M3). The following paragraphs lay out how growing railroad networks, through these three mechanisms, affect the costs and benefits, as well as the likelihood of success of separatist mobilization.

Figure 1. How Railroad Construction May Matter?

M1: Market Access and Social Communication

First and foremost, railroads affect local populations through economic integration and social communication. Improved connectivity to the entirety of a country’s territory, and especially to major cities, increases the costs of secession by making economic independence less attractive. It instead provides peripheral populations with material incentives to orient themselves toward an increasingly national economy and, in some cases, to even culturally assimilate into supralocal national identities. Mechanism M1 in Figure 1 schematically illustrates this point. The two railroad lines directly link the non-dominant population segment in the bottom-left corner to the two non-capital cities.

Industrial development is inextricably linked with railway construction.Footnote 4 Moving goods and people across large distances enabled the formation of integrated market economies and labor migration from agrarian towns to industrializing cities (Fishlow Reference Fishlow1965; Rostow Reference Rostow1960; Weber Reference Weber1976). Railway building contributed to city growth, increased employment shares in the industrial sector, and integrated markets in nineteenth century Europe (Alvarez-Palau, Díez-Minguela, and Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021; Berger Reference Berger2019; Berger and Enflo Reference Berger and Enflo2017; Hornung Reference Hornung2015; Keller and Shiue Reference Keller and Shiue2008). By the same token, urbanization and industrialization spurred railway construction as the earliest lines typically connected the major industrializing cities within a country (Hornung Reference Hornung2015). Where railways brought income-earning potential and prospects for upward mobility within national markets, local residents were unlikely to support separatist elites’ attempts to cut them off from these emerging opportunities (Hierro and Queralt Reference Hierro and Queralt2021).

Railways also accelerated the expansion of communication networks, brought previously isolated rural residents in contact with urban dwellers and each other, thus creating the bottom-up incentives and pressures for cultural homogeneization described by Gellner (Reference Gellner1983) and Deutsch (Reference Deutsch1953). Weber (Reference Weber1976, chap. 12) describes road and railway networks as technological precondition for “radical cultural change” in nationalizing France (Segal Reference Segal2016). Maier (Reference Maier2016) even uses the term “railroad nationalism” to describe the transformative effects of the transport revolution on national integration in Europe and the United States. Examples include minorities in integrating, western states, such as the Catalans in France and the Germans and Frisians in the Netherlands.

However, cultural difference may become more salient where members of distinct ethnic groups compete for inherently scarce modernization benefits (Bates Reference Bates, Rothchild and Olorunsola1983). Similarly, Gellner (Reference Gellner1983) explains how economic integration and information flows can make ethnically distinct peripheries acutely aware of their subordinate status and limited prospects for upward mobility which could increase support for separatist movements. While such a backlash effect is less prominently discussed in the literature, railroad expansion can, in principle, also increase peripheral populations’ motivations thus reducing the costs of elite-led separatist mobilization. This dynamic might be particularly acute in geographically isolated segments that experience large increases in domestic market access due to railway construction, such as the Finns who gained independence from the Russian Empire in 1917.

M2: State Reach and Direct Rule

A second and plausibly equally important mechanism links railroads to the central state’s ability to reach, govern, and transform local populations in top-down fashion. Providing public goods and engaging in ambitious state and nation-building policies would have been inconceivable without railroads (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018). Modern transportation infrastructure is part of what Mann (Reference Mann1993, 59) calls the “infrastructural power” of European states, which he defines as the “institutional capacity of a central state […] to penetrate its territories and logistically implement decisions.” Mechanism M2 in Figure 1 depicts this logic with a direct railroad link from the national capital to the main city in the culturally distinct non-dominant region. Here again, both local and non-local railway building matters as each kilometer of tracks constructed between the capital and the non-dominant segment implies reduced travel times from the political center.

Central states need to reach and penetrate peripheral areas to implement their preferred policies, monitor state-appointed bureaucrats, and, if necessary, repress unruly local elites and populations (Hechter Reference Hechter2000, 29). The prospect of state-repression increases the costs of separatist mobilization and lowers the chances of separatist success. Cermeño, Enflo, and Lindvall’s (Reference García-Jimeno, Iglesias and Yildirim2022) analysis of nineteenth century Sweden supports this view, showing how railways enabled public school inspectors to better reach peripheral districts, leading to higher enrollment rates and more nationalist curricula in connected locations. If railway-enabled public goods provision (Alesina and Reich Reference Alesina and Reich2015; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018), mass education (Alesina, Giuliano, and Reich Reference Alesina, Giuliano and Reich2021; Paglayan Reference Paglayan2021; Reference Paglayan2022), and policing capabilities (Mann Reference Mann1993; Müller-Crepon, Hunziker, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Hunziker and Cederman2021) induce loyalty as intended, local populations should have less motives and opportunities to support separatism. The Austro-Hungarians’ successful expansion of mass education to the Ukrainian parts of the Habsburg Empire fits this pattern (see, e.g., Darden Reference Darden2009), as do the French efforts to assimilate its periphery, including the Basques.

At the same time, however, increasing state penetration and top-down nation building (M2 in Figure 1) may spur backlashes where they proceed—or are perceived—as exploitative schemes of “internal colonialism” (Hechter Reference Hechter1977), thus nurturing popular and elite-level support for secession and facilitating separatist mobilization. In addition, the mere fact of “alien rule” by ethnically distinct central state elites, regardless of specific policies, appeared increasingly scandalous in nationalizing Europe (Hechter Reference Hechter2013). By bringing the state closer to peripheral elites and populations and thus threatening their status, power, and traditional ways of life, railroad networks can plausibly contribute to the emergence of “reactive nationalism” (Hechter Reference Hechter2000). The Russian Empire’s expansion of rail connections to the Polish lands facilitated separatist mobilization, including among railroad workers (Schenk Reference Schenk, Lonard and von Hirschhausen2011). The Tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire were met by Serb resistance in 1878 and 1910 (Hechter Reference Hechter2000; Malešević Reference Malešević2012).

M3: Internal Connectivity and Social Mobilization

Third, railroads can facilitate the coordination and collective action of peripheral opposition movements, thus lowering the costs of separatist mobilization. Mechanism M3 in Figure 1 shows how local rails within a culturally distinct subregion improve the internal connectedness of its residents. Rapidly spreading information and ideas as well as social ties between leaders, activists, and ordinary citizens are key ingredients to successful mobilization (Aidt, Leon-Ablan, and Satchell Reference Aidt, Leon-Ablan and Satchell2022; Granovetter Reference Granovetter1978; Kuran Reference Kuran1992; Shesterinina Reference Shesterinina2016).

In line with this notion, recent empirical studies illustrate how railroad connectivity contributed to the diffusion and growth of opposition movements in the 19th-century United States (García-Jimeno, Iglesias, and Yildirim Reference García-Jimeno, Iglesias and Yildirim2022), pre-democratic Sweden (Melander Reference Melander2021), and interwar Egypt (Brooke and Ketchley Reference Brooke and Ketchley2018). Similarly, denser peripheral road networks come with higher levels of organized violence against the state in Africa (Müller-Crepon, Hunziker, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Hunziker and Cederman2021). Specifically related to nation building, Deutsch (Reference Deutsch1953) expects ethnic conflict where social mobilization through improved communication happens before local assimilation into dominant national cultures. By boosting internal connectivity, often unintentionally, railroad construction may thus increase the opportunities for separatist mobilization and, via internal communications and exchange, promote identification with separatist movements. Reactive mobilization occurred in groups that were traversed by the state’s main railroad network, such as the Ukrainians and Belorussians in Tsarist Russia and the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire. Even some industrializing segments in Western Europe, such as the Catalans in Spain, benefited from increasing levels of internal connectivity and managed to resist the assimilationist and integrationist advances of the central state.

Deriving Testable Hypotheses

The three causal mechanisms just outlined generate ambiguous expectations as regards the link between railroad construction and separatism. On the one hand, railways provide the transportation and communication networks that integrationist modernization theories regard as essential for both bottom-up (M1) and top-down nation building (M2). On the other hand, both market integration (M1) and state penetration (M2) may spur local backlashes, and internal connections (M3) are likely to facilitate separatist mobilization. There are, however, several reasons to expect railroad construction in non-dominant areas to increase the risk of separatism, at least in the short term.

First, and as illustrated in Figure 1, newly built rails within the settlement area of a non-dominant group unambiguously improve internal connectivity, whereas market access and state reach also depend on non-local railways in other parts of the country. Second, both the market access and the state reach mechanism do not unequivocally point to integration but may also foster resistance and separatist mobilization. Third, the integrative and assimilationist effects of market integration, social communication, and state reach typically unfold gradually and only fully materialize in the longer term. Economic change and local industrialization tend to uproot local modes of production and systems of exchange before adaptation is complete and the benefits trickle down to broader segments of the local population. While contact and exchange through personal mobility and labor migration have the potential to foster cultural homogenization into overarching national identities, such cultural change typically evolves over a long time period. In France, this process lasted for a full century following the French Revolution (Weber Reference Weber1976). Similarly, state-led nation building policies such as mass schooling and compulsory military service target younger generations and will therefore take full effect decades after their first introduction (Blanc and Kubo Reference Blanc and Kubo2022). In contrast, backlash against market integration and state building often occurs immediately upon their arrival.

Thus, we expect the first railway connections in non-dominant regions to increase the risk of separatism. The effects of internal connectivity on coordination and social mobilization likely materialize in more immediate fashion than the integrative forces described above.Footnote 5 In addition, where local elites and populations regard incipient economic change and state penetration as threats, they face strong incentives to mobilize resistance before slow-moving assimilationist pressures undermine their local basis of support. We therefore state our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Railway construction in non-dominant regions increases the likelihood of separatist mobilization, at least in the short term.

The first task of the empirical analysis below is thus to test if there is any systematic relationship between local railroad construction and peripheral nationalism and, if yes, whether a first railway connection increases the potential for counter-state nationalism as hypothesized. To leave it at that, however, would be theoretically unsatisfying. European history provides numerous examples of both successful nation building and national disintegration. The conditions under which one or the other prevails appear as an equally, if not more, important puzzle than any general relationship between railroads and separatism.

Conditional Hypotheses

Specific contextual conditions are likely to shape the opportunities and motivations for separatist mobilization. We explore five cultural, demographic, political, and economic factors that either complicate top-down nation building or favor separatist mobilization.

First, large cultural distances make it harder for the state to reach, govern, and assimilate peripheral populations (Alesina and Reich Reference Alesina and Reich2015). Homogenizing populations speaking local dialects of the dominant language or at least belonging to the same linguistic family appears easier than bridging deeper cultural divides.

Second, where large majorities already speak some version of the state-sanctioned national language, the standardization across local dialects and assimilation of culturally more distinct but small national minorities becomes a realistic prospect. Conversely, national integration appears a much more daunting task where the state-leading nation represents relatively small shares of its country’s population.

Third, national independence campaigns only gain support where they can mount a credible challenge to the host state and offer the prospect of economic and military viability in case of successful secession (Siroky, Mueller, and Hechter Reference Siroky, Mueller and Hechter2016). Non-dominant groups with large populations and territories can more credibly promise sufficient state and market size after independence, and are therefore more likely to rally the required support than small national minorities (Hechter Reference Barbour and Carmichael2000, chap. 5; Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013, chap. 4).

Fourth, in underdeveloped countries, railway access likely brings in the central state but does not come with the economic benefits and opportunities of rapid industrialization, and peripheral populations have little incentives to become loyal to the center or invest in cultural assimilation. Under such conditions, claims about exploitation by the ruling elite are particularly likely to resonate with local populations (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1990, chap. 4).

Fifth, only high-capacity states can be expected to successfully implement direct rule and ambitious nation-building policies. Pre-existing levels of state and especially fiscal capacity developed through earlier processes of political reform, technology adoption, or economic integration are thus likely to matter (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018).

Last but not least, democratic institutions, especially liberal ones that protect all and, in particular, minority citizens against excesses of the state might make peripheral populations more likely to accept or even support direct rule by the center.

Based on these contextual arguments, we specify and test additional hypotheses on the link between railroads and separatism.

Hypothesis 2. Railway access increases the likelihood of separatist mobilization in…

-

(a) non-dominant groups that are culturally distant from the state-leading nation,

-

(b) countries with a relatively small dominant national group,

-

(c) large non-dominant groups,

-

(d) relatively poor and less industrialized countries,

-

(e) low-capacity states,

-

(f) staunchly autocratic states.

Network Structure and Specific Causal Mechanisms

Finally, we move beyond the short-term effects of the mere presence of a railway connection and investigate how more gradual and long-term improvements in connectivity relate to three mechanisms described above. The main drivers in bottom-up versions of integrationist modernization theory are industrial development, urbanization, as well as personal mobility and exchange over larger distances. This mechanism (M1 in Figure 1) should be particularly relevant where railway construction effectively integrates peripheral regions into national markets and improves local population’s access to the industrializing cities of the country. Provided that they do not trigger inter-group conflict or competition, railway lines that increase a region’s “market access” (Donaldson and Hornbeck Reference Donaldson and Hornbeck2016) can be expected to lower local incentives for separatism and contribute to growing identification with the state-framed national identity, especially in the long run.

In similar vein, top-down nation building through public goods provision, education, and repression requires fast and reliable transportation links between the state capital and potentially restive minority regions (M2). Separatist mobilization therefore seems less likely wherever newly constructed rails more directly connect peripheries with the administrative capital and the integrative effects of direct rule and top-down nation building prevail over local efforts to mobilize for separatism (M2 in Figure 1).

In addition, new transportation links can also boost internal connectivity within peripheral regions while only marginally increasing state reach or national market access (M3 in Figure 1). We thus test the following three, more long-term hypotheses linking the structure of expanding European railway networks to the likelihood of separatist mobilization.

Hypothesis 3. Railway-induced improvements in …

-

(a) …national market access reduce the likelihood of separatist mobilization (M1).

-

(b) …state reach reduce the likelihood of separatist mobilization (M2).

-

(c) …internal connectivity increase the likelihood of separatist mobilization (M3).

DATA AND VARIABLES

Our analysis requires a geographic unit of analysis below the country level from which separatist mobilization against the state likely emanates. In all analyses, we use yearly observations of ethnic segments, defined as the spatial intersections between country borders and ethnic settlement areas.Footnote 6

Ethnic Settlement Data

Information on historical ethnic settlements comes from the newly compiled Historical Ethnic Geography (HEG) dataset which is based on a selection of 73 historical maps (for details, see Section A1 of the Supplementary Material). Practically all ethnic categories appearing on our maps refer to linguistic rather than religious or regional ethnic identity markers, thus reflecting a well-known characteristic of European nationalism (Barbour and Carmichael Reference Barbour and Carmichael2000). We standardize all groups depicted on all maps with the help of the Ethnologue language tree (Lewis Reference Lewis2009) and construct a time-invariant master list. Finally, we draw on all maps belonging to a specific group-time period combination to construct a best-guess settlement polygon.

Historical State Borders

Spatial data on state borders since 1886 come from the CShapes 2.0 dataset that offers global coverage on all sovereign states and their dependencies since the “Scramble for Africa” (Schvitz et al. Reference Schvitz, Girardin, Ruegger, Weidmann, Cederman and Gleditsch2022). These data were extended for Europe back to 1816 drawing on non-spatial data from the Gleditsch and Ward (Reference Gleditsch and Ward1999) dataset of independent states, the Correlates of War’s Territorial Change dataset (Tir et al. Reference Tir, Schafer, Diehl and Goertz1998), and the Centennia Historical Atlas (Reed Reference Reed2008), with the addition of dozens of microstates that existed before the German and Italian unifications.

Units of Analysis

Spatially intersecting the aggregate group polygons with yearly data on European state borders yields our main unit of analysis – ethnic segments years from 1816 to 1945. For each segment year, we calculate absolute area and population. Historical population data come from the History Database of the Global Environment (HYDE; Goldewijk, Beusen, and Janssen Reference Goldewijk, Beusen and Janssen2010). Wherever ethnic segment or aggregate group polygons overlap, we equally divide area or population between overlapping polygons. As national dominant groups do not engage in separatism, our baseline analyses restrict the sample to non-dominant ethnic segment years. Dominant groups are identified as the the largest ethnic segment that contains the capital, subject to manual inspection and correction.

Main Independent Variable: Railway Access

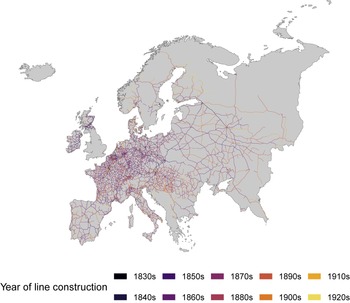

Segments’ access to railway networks serves as a geographically and temporally disaggregated proxy for the uneven spread of modernization. Geographic data on the expanding European railway network come from train.eryx.net, a website built by French train enthusiasts Bernard and Raymond Cima. They provide construction dates and map representations of all known railway segments covering almost all of geographic Europe, with the notable exception of England and Wales, which leads us to exclude the British Isles and Ireland from the analysis. We georeference their yearly online map tiles and digitize all line features to construct a geospatial dataset of European rails from the first railway built in 1834 to 1922.Footnote 7 Figure 2 plots our railroad data. Section A1 of the Supplementary Material validates the railroad data’s precision against time-varying railway maps for Austria–Hungary.

Figure 2. Geographic Data on Yearly Railway Construction

Note: Map is digitized from train.eryx.net.

The main treatment indicator in the analyses below is a dichotomous railroad access indicator derived from intersecting the yearly ethnic segment polygons with yearly line datasets of the European railway network. All segments intersected by a line feature are assumed to be connected. To operationalize mechanisms M1–M3, we use the network structure to compute continuous proxies for segments’ connectivity to national economic markets, state reach, and internal connectivity (see Section A4 of the Supplementary Material for details).

Outcomes: Attempted and/or Successful Secession

As described below, our main outcome variable captures violent and peaceful mobilization for separatism by combining onsets of separatist conflict, successful secessions, and political claims for national independence or regional autonomy (see Section A3.1 of the Supplementary Material).

First, we code a dummy of ethno-territorial civil war onset at the ethnic segment-year level. For the period 1816–1945,Footnote 8 we identify all unique civil wars listed in the datasets provided by Gleditsch (Reference Gleditsch2004) and Sarkees and Wayman (Reference Sarkees and Wayman2010) that were fought in the name of a specific ethnic group, focusing on ethnic claims and recruitment.

We combine the territorial conflict measure with a binary indicator of successful secession as an additional signal of national disintegration.Footnote 9 The secession dummy is coded one for all non-dominant ethnic segments that become dominant group segments in newly independent states in year

![]() $ t+1 $

.

$ t+1 $

.

Lastly, we add a new measure of nationalist claims to code the first claim for full national independence or regional autonomy within given state structures made by a nationalist organization at the level of ethnic segment years (see Section A5 of the Supplementary Material). In combination, the disintegration measure takes on the value of 1 if a segment experiences a secessionist conflict onset, claim, or secedes in a given year and 0 otherwise. Table A1 in the Supplementary Material presents descriptive statistics of all main dependent and independent variables.

ANALYSES AND RESULTS

This section summarizes our main specification and results, followed by a set of robustness checks. We then test our conditional hypotheses and present results on disaggregated mechanisms tests.

Main Specification and Results

Our baseline specification is a difference-in-differences (DiD) regression estimated as two-way fixed effects (TWFE) linear probability model with the time-varying railway access dummy described above as treatment variable. The dependent variable is a combined indicator of national disintegration for all segment-years with either a successful secession, a territorial civil war onset, or a separatist claim for independence or regional autonomy. We multiply this outcome by 100 to increase readability and facilitate interpretation in terms of percentage points. All baseline models include unit fixed effects for ethnic segments and time fixed effects for either years or country-years—the latter control for the potential of regionally concentrated diffusion of secessionism and other temporal shocks and trends that equally affect all segments within a given country (e.g., Cunningham and Sawyer Reference Cunningham and Sawyer2017). In addition, all models control for a count variable of past territorial civil wars since 1816 as well as peace year dummies for both civil war and nationalist claims to account for past secessionist mobilization and address concerns about reverse causation.

The identifying assumption in this setup is that counterfactual trends are parallel, which we discuss in more detail below. Recent methodological contributions have highlighted problems with TWFE models when it comes to accommodating heterogeneous treatment effects across treatment cohorts and effects evolving dynamically after the first treatment onset (e.g., Callaway and Sant’Anna Reference Callaway and Sant’Anna2021; Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2020; Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Sant’Anna, Bilinski and Poe2023). Therefore, we also implement two-stage estimators recently proposed by Gardner (Reference Gardner2022) and Liu, Wang, and Xu (Reference Liu, Wang and Yiqing2024), which are specifically suited to multi-cohort DiDs with staggered treatment adoption. By imputing counterfactual outcomes for treated units based on a first-stage regression, the 2S-DiD approach alleviates most of the weighting and comparison problems of conventional TWFE models. Section A7 of the Supplementary Material describes our choice of estimators in detail and shows robustness to alternative DiD specifications (Liu, Wang, and Xu Reference Liu, Wang and Yiqing2024).

Table 1 presents our main findings. Column 1 indicates that the probability of separatist claims, secessionist conflict fought in the name of a non-dominant ethnic segment, or successful secession increases by 1.49 percentage points after the first railway arrives. This effect is substantively large and amounts to a more than two-fold increase compared to the sample mean of 1.12 instances of separatist mobilization per one hundred ethnic segment years. Column 2 replaces year with country-year fixed effects which reduces the estimated coefficient by 28%. Columns 3 and 4 replicate the analysis but rely on the two-stage DiD estimator developed by Gardner (Reference Gardner2022). Both specifications yield substantively larger estimates than their TWFE-based counterparts in columns 1 and 2. The difference in magnitude can be explained by the mechanical downward biases that TWFE models create in staggered treatment settings when temporal effect heterogeneity exists (e.g., Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021, 261). Model 3 suggests an effect of railroads of more than 2 percentage points, equivalent to a 195% increase from the sample mean. The effects drops to a 158% increase when replacing year with country-year fixed effects (Model 4). These results suggest that, on average and contrary to naive interpretations of modernization theory, railway access contributed to separatist mobilization rather than stronger national cohesion and political stability in ethnic minority areas.

Table 1. Railroads and Separatism (1816–1945)

Note: The unit of analysis is the ethnic segment year. State-leading segments and segments smaller than 2,000 sqkm dropped. All models control for the number of past conflicts and peace years indicators. Segment clustered standard errors in parentheses. +

![]() $ p<0.1 $

, *

$ p<0.1 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05, $

**

$ p<0.05, $

**

![]() $ p<0.01 $

, ***

$ p<0.01 $

, ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

Interpreting these findings as causal requires the assumption of parallel counterfactual trends. As counterfactual outcomes are by definition unobservable, we have to assume that, in the absence of treatment, treated units would have evolved similarly after treatment onset as not-yet-treated or never-treated control observations. While this assumption cannot be empirically verified, we can investigate trends before treatment onset to assess its plausibility.

Figure 3 plots coefficients and confidence intervals from a dynamic DiD specification (“event study”) with segment and year fixed effects estimated via two-stage DiD. Instead of using a single post-treatment indicator, we now estimate coefficients for relative, five-year long time-to-treatment bins.Footnote 10 The first five-year bin before treatment onset is omitted and serves as the baseline category. We obtain similar results from an event study model using country-year instead of year fixed effects (see Figure A6 in the Supplementary Material). Both plots reveal mostly parallel outcome trends between untreated and treated units in the periods before the latter receive their first railway line. The pre-trend dummy coefficients remain relatively close to zero and are jointly insignificant in both models. However, two pre-treatment dummies in Figure 3 are negative and significant at the 5% level, which is not the case when using country-year fixed effects. The parallel trends prior to treatment make the identifying assumptions of our empirical strategy more plausible and should reduce concerns about endogenous railway building in response to separatist mobilization. The post-treatment dummies indicate an immediate increase in conflict risk after the first railway is built. The estimated treatment effects grow even larger approximately 35 years after the first railway and, if anything, diminish from the 50th post-treatment year onward (especially in the specification with country-year FE). These results clearly support Hypotheses 1 and cast doubts on prominent integrationist mechanisms. Whether these mechanisms are irrelevant or still operative but, on average, outweighed by countervailing effects is a question we address below.

Robustness Checks

Instrumental Variable Approach

An instrumental variables (IV) strategy based on simulated railways addresses remaining potentials for reverse causality and omitted variable bias, by which security considerations or other proximate causes of conflict motivate railway extensions. We simulate the evolution of railway networks by heuristically placing railroads for each country-year such that they maximize the connectedness of a state’s population (see Section A6 of the Supplementary Material; see also Müller-Crepon, Hunziker and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Hunziker and Cederman2021). The simulated development of the European railroad network is thus only determined by the yearly mileage built in each state, their borders, as well as the time-invariant population distribution as estimated for 1830 (Goldewijk, Beusen, and Janssen Reference Goldewijk, Beusen and Janssen2010), thus excluding potentially biasing military, demographic, or economic causes of railroad construction.

We use the presence of a simulated railroad in a segment as an instrument for observed railway access in a TWFE estimation strategy. The exclusion restriction assumes that the instrument affects separatism only through observed railroads and is not systematically affected by unobserved causes of conflict. Our segment fixed effects account for potential time-invariant omitted variables and year fixed effects capture temporal fluctuation in railroad expansion. We additionally show robustness to country-year fixed effects which account for state-specific railroad investments and border changes.

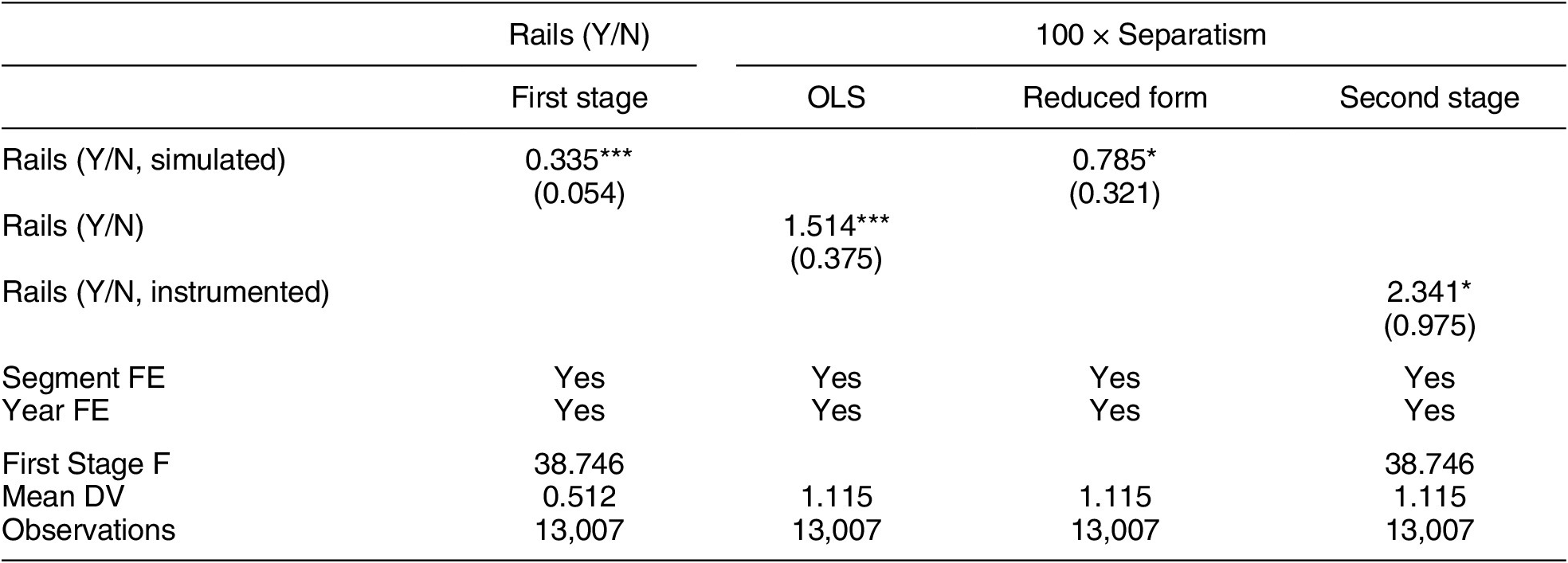

Column 1 in Table 2 shows that our instrument is strongly predictive of actual railway construction in ethnic segments (F-statistic of 39). Column 2 replicates our TWFE baseline to facilitate comparing naive to IV estimates. Columns 3 shows the reduced form regression of separatism on the instrument, whereas column 4 shows the second-stage estimate of instrumented rail access. Both coefficients are positive and statistically significant, yet less precisely estimated than the baseline TWFE effect. The second stage yields an estimate larger then the TWFE but similar in size to the 2S-DiD estimate (Table 1, Model 3). Replacing year with country-year fixed effects leads to stronger results (Table A3 in the Supplementary Material). These findings increase our confidence that the estimated effects are not merely reflecting reverse causation resulting from strategic railway construction or biases from temporally varying omitted variables.

Table 2. Instrumenting Railroad Access

Note: The unit of analysis is the ethnic segment year. State-leading segments and segments smaller than 2,000 sqkm dropped. All models control for the number of past conflicts and peace years indicators. Segment clustered standard errors in parentheses. +

![]() $ p<0.1 $

, *

$ p<0.1 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01, $

***

$ p<0.01, $

***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

Sample Definitions

As an alternative to controlling for past conflict in our baseline models, we run a robustness check that drops all ethnic segment-years as soon as they experience a secessionist civil war or nationalist claims. The results are summarized in Table A4 in the Supplementary Material and show substantively smaller, yet positive and significant, treatment effects. These estimates also treat all separatism outcomes equally by censoring observations after the first onset of separatism. Therefore the models can be interpreted as the effect of railways on the risk of separatism given no previous separatist effort. In addition, we replicate our baseline results using a subsample that excludes all never-treated units. If ethnic segments that never received a railway connection before 1922 are too small, rural, and peripheral to serve as valid comparison group for modernizing segments, their inclusion may reduce the credibility of parallel counterfactual trends and lead to biased conclusions. Table A5 in the Supplementary Material shows similar or, when using the two-stage DiD estimator, significantly larger treatment effects. Finally, we replicate our main findings by censoring the sample in 1922, the year in which our railway data stop. Results in Tables A6–A7 and Figure A7 in the Supplementary Material are robust, showing estimates that are of the same or larger size than in the main specification.

Outcome Disaggregation

We furthermore disaggregate the outcome variable and report separate regressions for successful secessions, secessionist civil wars, and national independence or autonomy claims. The results in Tables A9–A10 in the Supplementary Material suggest that our baseline findings are mainly driven by territorial civil wars and nationalist claims. That said, the estimated effects on the most extreme (and rare) outcome of successful secession are positive and reach significance when estimated as two-stage DiD but substantively small and insignificant in the TWFE setup.

Including Irredentism

The combined outcome in the main analysis does not include irredentist claims, that is demands of non-dominant groups to secede from the current state and be transferred to a neighboring ethnic kin state. These claims mostly co-occur with independence claims. As an additional robustness test, we replicate the main analysis including seven additional irredentist claim onsets. Unsurprisingly, the estimates in Table A11 in the Supplementary Material and the event study plots in Figure A11 in the Supplementary Material closely match the main results without irredentism.

Testing Conditional Hypotheses

To test the conditional Hypotheses 2, we replicate the baseline model from column 1 in Table 1 while interacting the railway access dummy with moderating variables coded at the segment- and country-year level. Figure 4 displays marginal effect plots along with the binning estimates as proposed by Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Yiqing2019). Detailed results are presented in Tables A12 and A13 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 4. Marginal Effect Plots and Binning Estimates

Note: The linear interaction estimates derive from models in Table A12 in the Supplementary Material; binned estimates from Table A13 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 4a tests whether the destabilizing effect of rails is stronger in ethnic segments that are culturally more distinct from the state-leading group (H2a). We calculate linguistic distance from the dominant group by matching the ethnic categories from our maps to the Ethnologue language tree. Interacting the rail treatment with linguistic distance yields a positive but merely weakly significant coefficient (Model 1 in Table A13 in the Supplementary Material). For example, separatist conflict took place both between linguistically similar groups such as Catalans and Spanish and distant ones such as Germans and Hungarians. One interpretation of this non-result is that conditional on some cultural difference, group-level politicization and mobilization processes are more important than cultural distance.

Figure 4b interacts the rail indicator with the country-year-level population share of the dominant national group. Consistent with H2b, the interaction coefficient is negative and significant suggesting local railways are particularly likely to spur nationalist independence campaigns in countries with relatively small ruling groups. However, the binning plot in Figure 4b suggests that the significant linear interaction term is likely due to a small number of cases with particularly small dominant groups.Footnote 11 The binning coefficients show that there are no significantly different effects in the lowest, intermediate, and highest tertiles of the distribution of national dominant group’s population share.

Figure 4c tests our argument about non-dominant groups’ opportunities to engage in separatism. The results reveal that railways mainly spur separatism in demographically large ethnic segments, in line with H2c. Examples of large ethnic segments that mobilize are Belorussians, Poles and Ukrainians in Russia, and Czechs, Hungarians and Italians in Austria–Hungary. In contrast, railroad access has a negative effect in very small ethnic segments, in which it is likely more difficult to stage a separatist movement against the forces of state and market integration.

To test H2d and H2e, we rely on per capita GDP and fiscal capacity measures from the historical V-Dem data (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman and Bernhard2016). The negative and significant linear interaction with per capita income in Figure 4d suggests that our findings are driven by relatively poor and arguably less industrialized country-years in the sample, thus confirming H2d. Similarly, the binning estimates for fiscal capacity in Figure 4e suggest that the effect of railway access is significantly larger at typically low values of fiscal capacity than at typical medium or high values, consistent with H2e. The cases of separatism in less developed states with lower fiscal capacity mostly fall in the Russian and Ottoman Empires and in their successor states.

Finally, the interaction term with the V-Dem liberal democracy score (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman and Bernhard2016) is negative and significant (Figure 4f). However, the binning estimates reveal that, if anything, the effect is highest at low-to-intermediate values of liberal democracy, which mostly occur in the Ottoman and Russian Empires during the second half of the nineteenth century. While the rail effect in the most democratic tertile is significantly smaller in the intermediate one, it is not significantly lower than among observations in the lowest tertile.

Exploring Causal Mechanisms

Finally, we attempt to separate the three mechanisms through which railway construction affect center-periphery bargaining and separatist mobilization as outlined in the theory. Thus, we compute railway-based proxies for (1) segments’ economic market access (H3a) as their average travel time toward large cities (logged due to its skew),Footnote 12 (2) local state reach (H3b) as the inverted average travel time to the capital, and (3) segments’ internal connectivity (H3c) as the invertedFootnote 13 average travel time among their inhabitants.Footnote 14 In the main analysis, we use time-invariant population data from before the arrival of railroads to avoid biases from endogenous population developments. However, our results remain consistent when we compute all network statistics using time-variant population data (Tables A15 and A16 in Section A10 in the Supplementary Material). Table 3 shows TWFE models of separatism where these variables replace our baseline railway dummy variable. Given the continuous nature of our network measures, we cannot estimate difference-in-difference models as in the main analysis, thus requiring stronger assumptions on the absence of (time-variant) omitted variables and reverse causality.

Table 3. Network Structure and Causal Mechanisms

Note: The unit of analysis is the ethnic segment year. State-leading segments and segments smaller than 2,000 sqkm dropped. All models control for the number of past conflicts and peace years indicators. Segment clustered standard errors in parentheses. +

![]() $ p<0.1 $

, *

$ p<0.1 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

, ***

$ p<0.01 $

, ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

All coefficient estimates point in the expected direction and, with the exception of National Market Access in columns 1 and 4, reach conventional significance levels. In line with top-down mechanisms of state-sponsored nation building, better links to the national capital come with substantive reductions in the likelihood of separatist mobilization as predicted by Hypothesis H3b. Improving state reach by one standard deviation leads to a decrease in the risk of separatism onsets by 0.79 percentage points or 70% of the average risk. The effect of internal connectivity (M3 in Figure 1) points toward a higher capacity of local elites and populations to organize collective action against the state, which is consistent with Hypothesis H3c. Increasing segments’ internal connectivity by one standard deviation comes with an increase in the risk of separatism onsets by 0.34 percentage points.Footnote 15 The negative and borderline significant coefficient of National Market Access turns substantively small and statistically insignificant when also including state reach, which suggests that most of the negative effect in the first model is driven by better connections to the capital city. Additional analyses in Section A10 in the Supplementary Material show that these results are robust to adding country-year fixed effects (Table A18 in the Supplementary Material) and controlling for leads of the independent variable that capture potential reverse causality (Tables A19 and A20 in the Supplementary Material).

These results provide stronger support for the political and mobilization-related mechanisms M2 and M3 than for nation building via market integration and social communication (M1). Another interpretation is that increasingly integrated national railroad networks exert heterogeneous effects across different contexts and that, on average, integrative and disintegrative responses balance each other out.Footnote 16 The fact that our baseline analysis shows positive effects of the first railway link in a segment may thus be due to peripheral connections in historical Europe mainly strengthening local ties rather than effectively boosting state capacity or integrating national markets.

That said, these findings by no means imply that reactive nationalism and local resistance against direct rule are irrelevant. Such resistance needs to occur before it is too late, that is, after railway access and internal connectivity improve local mobilization capacity, but before the state assimilates peripheral populations (Deutsch Reference Deutsch1953). In addition, a more selective indicator for culturally distinctive direct rule of “nationalizing” states (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996) could yield different results.

CONCLUSION

Modern transportation infrastructure is conventionally seen as having strengthened European state and nation building. Expanding railway networks boosted centralizing states’ infrastructural power and enabled increasingly direct forms of governance, while spurring economic change, urbanization, and social contact over increasing distance.

Extrapolating from Weber’s (Reference Weber1976) study of nationalizing France, many social scientists expect these changes to have strengthened national cohesion well beyond the French case. Yet, this paper shows that, if anything, railway construction in ethnic minority regions tended to threaten the integrity of European states and empires. Our analyses suggest that separatism became more likely after territories inhabited by non-leading ethnic groups were connected to the state’s railroad network. Our conditional analysis reveals some structural dimensions that hindered national integration in multi-ethnic states, especially in Eastern Europe. Large minority groups, small population shares of state-leading groups, weak levels of state capacity and per capita income posed formidable challenges for state centralization and top-down nation building. Thus, the French experience appears more as an exception than a paradigmatic case of nation building in Europe.

We also show how the aggregate effects of railroad access mask varying effects of the networks’ overall structure. Results from our analyses of causal mechanisms suggest that separatism becomes more likely where railroads facilitate mobilization by improving internal connectivity of peripheral ethnic regions but less likely where it brings such regions closer to the state’s capital. National market access, however, does not seem to make a difference.

Railway construction was only one, though arguably the most important, vector of modernization in Europe from the nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century. In this sense, the current study contributes to a broader literature that analyzes national integration or disintegration through various means of social communication and mechanisms of identity formation, such as telegraph lines, road networks, mass education, and mass media. There is a growing research agenda analyzing how mobilization processes around the world are influenced by more recent technologies, such as broadcasting (Warren Reference Warren2014), cell-phone technology (Shapiro and Weidmann Reference Shapiro and Weidmann2015), or social media (Gohdes Reference Gohdes2020; Weidmann Reference Weidmann2015). While our study serves as a reminder that technological advances sometimes have disintegrating effects, careful empirical research is needed before applying our findings to settings beyond the classical cases of European nation building.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425000048.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EVF0DN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Previous versions were presented at EPSA in June 2023; Oxford University on March 20, 2023; the London School of Economics on March 21, 2023; University of Gothenburg, March 2023; University College London Conflict & Change group in January 2023; the Hertie School in Berlin, November 2022; the Graduate Institute in Geneva, October 2022; APSA Annual Meeting in Montreal, September 2022; the Princeton LISD and IPERG-UB Workshop on National Identity in Barcelona, May 2022; and the Zurich Political Economy Seminar Series, June 2022. We thank the discussants (Idil Yildiz, Scott Gates, Patrick Kuhn, Leonid Peisakhin, Bruno Caprettini) and participants of these workshops for their valuable comments and suggestions. We thank the participants of those presentations for excellent feedback.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the Advanced ERC Grant 787478 NASTAC, “Nationalist State Transformation and Conflict.”

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.