INTRODUCTION

Institutions theorists seek to explain institutional stability and change. However, most accounts have a status quo bias, as institutions are portrayed as stable. When change is observed, it is typically through alterations of the formal rules of the institution. These changes are frequently attributed to easily observable exogenous factors, such as external crises, influxes of new ideas, or alterations in actors’ power. However, endogenous processes may also create change and their neglect biases our accounts of institutions.

This paper advances a theory of endogenous institutional change whereby members of an institution react differently to the outcomes of disputes within institutions. Losers (or those who disagree with the outcomes of the disputes) may become demotivated and disempowered, whereas the winners (or those who agree with the outcomes of the disputes) may become galvanized and empowered. If the winners and losers belong to coherent camps with divergent interests and ideas about the institution, disproportionate exits by the losers can cause drastic institutional changes over time. The contribution of this paper is to show theoretically and empirically that consequential change can occur solely endogenously and that population loss can be the mechanism behind such change.Footnote 1

The paper provides a detailed demonstration of this occurring on the English Wikipedia. Beneath the hood of this popular website exists a large community of volunteers (Wikipedia editors) who collaboratively write all Wikipedia content. This population of volunteers comes together in deliberative and democratic fora where they adjudicate what kind of content belongs on the encyclopedia. This paper shows that the English Wikipedia transformed its content over time through a gradual reinterpretation of its ambiguous Neutral Point of View (NPOV) guideline, the core rule regarding content on Wikipedia. This had meaningful consequences, turning an organization that used to lend credence and false balance to pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and extremism into a proactive debunker, fact-checker and identifier of fringe discourse. There are several steps to the transformation. First, Wikipedians disputed how to apply the NPOV rule in specific instances in various corners of the encyclopedia. Second, the earliest contentious disputes were resolved against Wikipedians who were more supportive of or lenient toward conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and conservatism, and in favor of Wikipedians whose understandings of the NPOV guideline were decisively anti-fringe. Third, the resolutions of these disputes enhanced the institutional power of the latter Wikipedians, whereas it led to the demobilization and exit of the pro-fringe Wikipedians. A power imbalance early on deepened over time due to disproportionate exits of demotivated, unsuccessful pro-fringe Wikipedia editors. Fourth, this meant that the remaining Wikipedia editor population, freed from pushback, increasingly interpreted and implemented the NPOV guideline in an anti-fringe manner. This endogenous process led to a gradual but highly consequential reinterpretation of the NPOV guideline throughout the encyclopedia.

The paper demonstrates these processes through qualitative content analysis, archival research, and process tracing. First, to document a transformation in Wikipedia’s content, a qualitative content analysis was conducted on a sample of 63 representative articles. Content on the pages was analyzed across time with a predetermined coding scheme (see Boreus and Bergström Reference Boreus and Bergström2017; Elkins, Spitzer, and Tallberg Reference Elkins, Spitzer and Tallberg2021; Herrera and Braumoeller Reference Herrera and Braumoeller2004). The analysis shows that the content changed over time from lending credence to fringe views to delegitimizing the fringe views. Second, to explain why these content changes occurred, the paper uses process tracing on Wikipedia’s archives, analyzing article talk page discussions about rule interpretations, related discussions on general noticeboards, arbitration rulings, and editor sanctions proceedings, as well as the histories of individual Wikipedia editors. Analyses of debates regarding individual articles lend strong support for the theory of endogenous institutional change. Article-by-article evidence is supplemented by an analysis of a sample of referenda where editors are asked to express their views about the NPOV rule’s application to fringe topics. The analysis shows that the disproportionate population loss is systematic across the encyclopedia, as editors who hold the pro-fringe view exit Wikipedia at a higher rate than anti-fringe editors.

These changes occurred despite structural biases in favor of stability. Even though the rules and content on Wikipedia are constantly subject to change, the organization’s decision-making procedures are biased to a conservative status quo. All changes on Wikipedia must be approved through consensus and editors who act contrary to consensus are punished. Furthermore, the transformation was neither an inevitability nor likely outcome of the original design of the institution. A comparison to other versions of Wikipedia demonstrates the contingent nature of the English Wikipedia’s trajectory. For example, even though the Croatian and English Wikipedia share the same core rules, content on the two versions of Wikipedia looks drastically different, as the Croatian Wikipedia lends credence to anti-LGBT rhetoric and pseudohistory (Sampson Reference Sampson2013). These outcomes were not intended by Wikipedia’s founders, as shown by their own delineation of the rules in the early years, and in the case of Wikipedia’s co-founder, a complete disavowal of Wikipedia’s transformation.

This paper uses the understudied politics of Wikipedia as a lens through which to examine institutional theories of change. It has two major contributions. One is theoretical, demonstrating how population loss can be an endogenous mechanism of institutional change. Losses in institutional clashes can be demoralizing and inhibiting for the losers, leading them to abandon the institution and leaving the institution in the hands of their adversaries. The winners subsequently have freer rein to push for changes in the institution. This form of change may potentially have explanatory value regarding the trajectories of bureaucracies, political movements, political parties, and professions, as discontented losers within those institutions opt to leave their institution rather than fight an uphill battle against empowered and emboldened winners.

The other contribution is empirical, as the paper provides a comprehensive study of the politics of Wikipedia, a highly consequential organization in the online political information ecosystem. The paper documents a heretofore undocumented transformation in Wikipedia’s content over its life span. While scholars and commentators have remarked in recent years on Wikipedia’s status as a beacon of information in an online space plagued by misinformation, there is no comprehensive analysis of a transformation over Wikipedia’s life span.Footnote 2

INSTITUTIONS AND ENDOGENOUS CHANGE

Most scholarly works on institutions have a status quo bias, as the focus is on accounting for the persistence of institutional arrangements over time. To explain change, scholars tend to look for exogenous factors. For rational choice institutionalists, institutions reflect equilibrium solutions to problems of cooperation between different actors.Footnote 3 In most rationalist accounts of institutions, these equilibria do not become unstable unless the external circumstances change (e.g., through alterations in power), and the appearance of new problems that require new solutions. For sociological institutionalists, institutions reflect shared norms and understandings.Footnote 4 Actors that compose the membership of an institution exist in a social environment where institutional practices become taken for granted. Individual actors have limited agency to alter the existing institutional arrangements. These shared norms do not get altered unless by powerful external sources or through the appearance of norm entrepreneurs. For historical institutionalists, institutions reflect decision-making made at critical junctures, temporal sequencing, and path dependency. Past decision-making has a persistent impact on institutions, contributing to stability over time, even if the existing arrangements are suboptimal. The sources of change tend to be external crises or changes in the broader environment that alter the functions and purpose of institutions.Footnote 5

Recent comparative politics scholarship (particularly in the historical institutionalist tradition; see Bleich Reference Bleich2018; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009; Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005; Thelen Reference Thelen2004) and international relations-oriented research on norm contestation (see Dietelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Dietelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2008; Sandholtz and Stiles Reference Sandholtz and Stiles2009; Wiener Reference Wiener2009) have identified rule ambiguity and norm ambiguity, respectively, as promising plausible mechanisms for gradual endogenous change.Footnote 6 The seeds of change lie in the intrinsic inability of rules to apply clearly and unambiguously to most situations that confront members of complex institutions. This permits actors to reinterpret rules and norms through their application in specific instances. However, while this literature points to the plausibility of endogenous institutional change through ambiguity in rule application, many cases are prompted by exogenous causes, such as (i) the involvement of new actors, (ii) environmentally driven changes in the balance of power between actors, and (iii) the appearance of new problems that need solving. While these may be gradual processes of change, the underlying causes are frequently exogenous.Footnote 7

A prominent example of this kind of change in the comparative politics literature is Bleich’s (Reference Bleich2018) study of the French High Court’s changing interpretation of hate crime laws over time. Bleich’s explanation for the shift in how the court applied the rules focuses on the entry and influence of new actors, as he delineates how activist organizations influenced how the French High Court interpreted hate crime laws. He also shows that the French High Court was influenced by the European Court of Human Rights. In the international relations literature, a prominent example of this kind of change is Sandholtz’s (Reference Sandholtz2008) study on the rules regarding wartime plunder of artistic and cultural artifacts. In Sandholtz’s study, rules regarding wartime plunder were reinterpreted after major wars (the Napoleonic Wars and World War II), as the victims of large-scale plunder pressed to regain their property. In both cases, the rules in question (hate crime laws and rules of war) were broad and unspecified, allowing for different application of the rules in practice. In both Bleich (Reference Bleich2018) and Sandholtz (Reference Sandholtz2008), a lack of specificity in the wording of the rules permitted changes in application over time, but those changes were caused by exogenous factors (new actors or major wars).

My account of institutional change on Wikipedia contrasts with these other accounts in three ways. First, change was not caused by the entry of new actors, but rather the loss of actors. Whereas other approaches to the study of institutions tend to see the relevant population of an institution as being stable or increasing, my account shows that the loss of a particular population contributed to Wikipedia’s shift. Furthermore, other accounts see conflicts within institutions as resulting in winners and losers where the losers typically remain within the institution. As Conran and Thelen (Reference Conran, Thelen, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016) note, losers remobilize and live to fight another day, which may lead them to change the institution in the future. However, the extent to which that is true depends on the nature of the institution, as well as the characteristics of the conflicts and the participants involved. Losses may entrench power advantages that entail feedback effects and are hard to rebalance, thus ensuring that losers cannot return the institution to the status quo. That was certainly the case on Wikipedia.

Second, power asymmetries are formed on Wikipedia. However, unlike many other studies of institutions, the power asymmetry was not due to broader environmental changes that altered the social or material sources of actors’ power. Rather, power asymmetries formed as actors gained power within the rubrics of the institution itself. In the case of Wikipedia, experience provided a potent source of power, which made victories in early disputes consequential. In other organizations, there may be other power dynamics that are made apparent and entrenched through wins and losses in institutional conflicts.

Third, reinterpretation of Wikipedia’s rules was not prompted by the appearance of new problems that required new solutions. Rather, the practical consequence of the rule reinterpretations on Wikipedia entailed fixing old problems (the presence of sources and content that legitimized fringe perspectives) that in large part stemmed from how the rules had been interpreted in the past.

In contrast to much of the existing literature, this paper argues that institutions which are otherwise portrayed as stable are in fact constantly subject to change from within. The change can occur entirely endogenously.Footnote 8 There are four steps to such change. First, consistent with some of the historical institutionalist and norm scholarship, the seeds of change are located in the intrinsic inability of rules and norms to apply clearly and unambiguously to most situations that confront members of the institution. Second, rule ambiguity creates openings for members to impose new meanings on the rules at the micro level, as the rules are applied to specific situations. Since institutions are composed of actors that have different interests and diverse views, rule interpretations can be a potent source of conflict. Third, the conflicts may be resolved, resulting in winners and losers. The resolutions of these conflicts in favor of actors with certain rule interpretations can alter the balance of power within the institution, as the losers of past conflicts get demobilized, sanctioned, or lose status, whereas the winners get mobilized, elevated, and gain institutional power. Fourth, if actors with similar and overlapping viewpoints and interests (coherent camps) win early and frequent victories across an institution, they may shape how the overarching rules of the institution are understood to work in practice.

For the process to play out in this manner, camps with coherent interests and views must exist (A and B in Figure 1). Otherwise, settlements in individual disputes lead to indeterminate long-term results. Additionally, for trajectories to form over time, victories must result in power advantages. In the absence of a meaningful power advantage, losers should be able to regroup and live to fight another day over the interpretation of the rules, with indeterminate long-term results. The relative ease with which actors can exit institutions affects the speed of change. Migrating from a country may entail considerable costs, whereas leaving a voluntary association may be relatively cost-free, which means that rapid change may be more likely in the latter case once a power asymmetry forms. Finally, for the process to play out in this specific manner, it presumes that exogenous factors do not intervene with the process. Both exogenous and endogenous factors can work in tandem, but the contribution of this paper is to show theoretically and empirically that consequential change can occur solely endogenously.

Figure 1. How Do Rules Obtain New Meanings?Footnote 9

The remainder of this paper provides a detailed demonstration of how this process of endogenous change plays on the English Wikipedia. The paper explains what Wikipedia is, justifies why Wikipedia is a worthy case of inquiry, documents how Wikipedia’s content has transformed over its life span, and explains how this transformation happened. The penultimate section of the paper examines various alternative explanations, showing that they fail to account for Wikipedia’s transformation.

WIKIPEDIA AS AN IMPORTANT PART OF THE POLITICAL INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM

The Structure of Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a nonprofit, multilingual, open-access online encyclopedia started by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger in 2001. The encyclopedia is user-generated. Anyone is free to edit it. By May 2021, there were more than 40 million registered users, of whom nearly 140,000 were active editors. Wikipedians generally edit pseudonymously, but extant data indicate that Wikipedians are disproportionately white males from the Global North. One in four Wikipedians primarily edit the English language version of Wikipedia (see Hill and Shaw Reference Hill and Shaw2013; Wikipedia 2021b; Yasseri, Sumi, and Kertesz Reference Yasseri, Sumi and Kertesz2012b).

Editors must comply with three core Wikipedia content guidelines:

-

1. Neutral point of view (WP:NPOV): “representing fairly, proportionately, and, as far as possible, without editorial bias, all the significant views that have been published by reliable sources on a topic” (Wikipedia 2020a).

-

2. No original research (WP:NOR): “you must be able to cite reliable, published sources that are directly related to the topic of the article, and directly support the material being presented” (Wikipedia 2020b).

-

3. Verifiability (WP:V): “verifiability means other people using the encyclopedia can check that the information comes from a reliable source… All material in Wikipedia mainspace, including everything in articles, lists and captions, must be verifiable” (Wikipedia 2020c).

WP:NPOV is the guideline at the heart of most disputes on the encyclopedia. The NPOV guideline affects whether something should be covered, the weight of the coverage, and whether the cited sources are reliable. On subjects where there are diverse and incompatible views, “edit wars” frequently arise. These are situations when a change is made to an article (e.g., removal of text, addition of text, and rewording of text), and the change gets reverted, leading to an unstable cycle of additions and reverts of the same content (see Jemielniak Reference Jemielniak2014; Tkacz Reference Tkacz2015; Yasseri et al. Reference Yasseri, Sumi, Rung, Kornai and Kertesz2012).

How does the encyclopedia deal with disputes like these? One might think that such disputes would lead to an inconsistent product where articles look drastically different from day to day, but Wikipedia produces a very stable and consistent product. This is because there are multilayered dispute settlement mechanisms and elaborate norms regarding editor behavior. Wikipedia’s community reaches decisions about rules and content through a combination of deliberative discussions and referenda. These democratic processes have the goal of determining whether content has “consensus.” If a proposed change does not have consensus, the article experiencing edit wars will be returned to the status quo.

A typical edit war will be resolved in the following manner: an editor makes changes to a page. Other editors disapprove of the change and revert the change. The status quo ante is established until a consensus for inclusion can be found on the talk page of the article. Editors may be able to work out mutually acceptable compromises. If they are not able to work out acceptable compromises among the small subset that are engaged with a single article, they can subject the dispute to input from the broader Wikipedia community. For example, if the editors who edit the Margaret Thatcher page are having a dispute that they cannot resolve among themselves, they may take the dispute to noticeboards that are frequented by large numbers of Wikipedians who do not frequent the Thatcher page.

However, these procedures are not always sufficient to establish stability on a page. This is particularly the case on large high-profile articles with stable and coherent camps of editors, frequent editing, and multiple controversial aspects. When articles experience extraordinary levels of edit-warring, editors may request dispute settlement before administrators on the “Administrators Noticeboard” or arbitrators on the “Arbitration Committee.” These bodies primarily adjudicate behavioral problems among Wikipedians rather than adjudicate content directly (that is something for Wikipedia’s deliberative democratic processes to resolve). The bodies tend to sanction the most active and raucous editors on the dysfunctional pages.

Administrators and arbitrators are elected by the Wikipedia userbase. To become an administrator, an editor goes through the “Request for Adminship” process, which is essentially an election on the suitability of an editor to become an administrator. Any experienced editor can make a request for a position as administrator.Footnote 10 The request is unlikely to be granted unless they have a well-established history as a contributor on the encyclopedia and have demonstrated an ability to get along with other editors. The threshold to become an administrator is high, as editors generally require support by 75% of voters. Editors who are new and who behave in divisive ways are unlikely to get the support needed to become administrators.Footnote 11 The English Wikipedia has approximately one thousand administrators.

The Arbitration Committee is vastly smaller, with membership oscillating between 13 and 18 members. Elections to the Arbitration Committee are more formal and eventful processes than the requests for adminship, as the elections occur annually, eligible registered editors are notified about the elections on their user talk page, and cast secret ballots.Footnote 12 Experienced editors who are not divisive are better poised to garner the votes to become arbitrators.

Case Selection Justification

There are several motivating factors in choosing the English Wikipedia as a case to study institutional change: (i) it is an important case; (ii) it is an understudied case; (iii) it could be construed as a least-likely case for institutional change; and (iv) it has unique availability of data, which makes it possible to observe slow, gradual, endogenous processes that result in consequential drastic change over time.

First, Wikipedia is an important institution. One that is worthwhile to study in its own right. Wikipedia.org is one of the most popular websites in the world. The English Wikipedia is frequently at the top or near the top of Google searches for a known person or event in the English language (e.g., Vincent and Hecht Reference Vincent and Hecht2021). Wikipedia is also widely perceived as a trustworthy and reliable source of information (e.g., Bruckman Reference Bruckman2022), giving it considerable power in public discourse and ideational diffusion. Wikipedia’s influence is also boosted by the fact that Wikipedia pages, unlike other forms of content (such as news reports and scholarship), are often written in summary style and in layman’s terms, thus making the information in Wikipedia articles more accessible to readers. Furthermore, tech giants, such as YouTube, Facebook, Google, and Twitter, have incorporated Wikipedia into their own platforms.

Due to its popularity and perceived trustworthiness, Wikipedia has the power to legitimize and delegitimize subjects. This is a website that can declare whether something is a pseudoscience, a falsehood, a conspiracy theory, or bigotry. World leaders can be described as dictators, perpetrators of violence can be identified, and the effects of implementing certain public policies can be characterized as positive or negative. Additionally, in many cases, it seems clear that actors who are covered by Wikipedia believe that Wikipedia matters, as politicians have on many occasions been exposed as having edited their own Wikipedia pages, and authoritarian regimes have blocked Wikipedia in parts or in its entirety.

Wikipedia’s salience has increased over time, as scholars express concern over the intersection of the Internet and politics. The Internet has displaced traditional gatekeepers, and contributed to the wide diffusion of conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and extremist rhetoric. Whereas the other major online platforms have been criticized for their role in monetizing, inculcating, and diffusing extremism and misinformation, Wikipedia has often been hailed as an exception: a distinctly positive actor in the online political ecosystem,Footnote 13 an actor that serves a proactive gatekeeping role where it outright debunks, fact-checks, and highlights the errors and fringe nature of the very same discourses popularized on the other platforms.

Second, Wikipedia is an understudied institution in an understudied organizational environment. Aside from its importance in politics, there are several things about Wikipedia as an organization that political scientists and organizational scholars should find intriguing. It is an enormous organization that is based on the open-source or commons-based peer production organizational model (e.g., Benkler Reference Benkler2002; Reagle Reference Reagle2010; Tkacz Reference Tkacz2015). Unlike traditional organizations, such as firms and bureaucracies, Wikipedia is characterized by a lack of “formal hierarchy.” Editors on Wikipedia are not managed and instructed by “managers,” but rather self-assign tasks to do. Editors are not motivated by monetary rewards, unlike members of traditional organizations.

Decision-making on Wikipedia is deliberative and democratic. The rules of Wikipedia are always subject to change, which effectively makes all rules, norms, and content on Wikipedia subject to constant plebiscites. Consequently, Wikipedia both reflects and accentuates processes that are analogous to those in other organizations. Scholars have consequentially used Wikipedia to study collaboration, conflict, polarization, and partisanship, as well as politics and organizational dynamics more broadly (Greenstein, Gu, and Zhu Reference Greenstein, Gu and Zhu2021; Heaberlin and DeDeo Reference Heaberlin and DeDeo2016; Jemielniak Reference Jemielniak2014; Konieczsny 2009; Lerner and Lomi Reference Lerner and Lomi2019; Reagle Reference Reagle2010; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Teplitskiy, Duede and Evans2019; Tkacz Reference Tkacz2015; Yasseri et al. Reference Yasseri, Sumi, Rung, Kornai and Kertesz2012; Yasseri, Sumi, and Kertesz Reference Yasseri, Sumi and Kertesz2012). While Wikipedia has been the subject of study by computer scientists, physicists, information scientists, and sociologists, it has been neglected by political scientists.

Third, Wikipedia could be construed as a least-likely case for institutional change and most-likely case for organizational stability, as the organization has several structural biases in favor of stability and the status quo. The requirement that there needs to be a “consensus” among editors in favor of both addition of content and rule changes should make it hard to enact substantial changes.Footnote 14 In the event of disputes, the guiding rule is to retain the status quo unless a consensus can be established for any change. A minority of editors can therefore block controversial changes. Furthermore, the presence of a large and diverse userbase means that ideational changes among individuals and small groups should not result in frequent or sudden changes over time. Wikipedia also strongly enforces compliance with the rules, which means that large-scale rule violations will not be a likely source of change over time (see Piskorski and Gorbatai Reference Piskorski and Gorbatai2017). The strong enforcement leads editors to edit within accepted boundaries and within consensuses. Given these institutional characteristics, one might expect Wikipedia to have a conservative status quo bias.Footnote 15

Furthermore, the founders of Wikipedia have not intervened to cause new interpretations of the guidelines among the userbase. Sanger, who crafted the core NPOV rule, has condemned the interpretations of the guideline that emerged over time.Footnote 16 Wales has held a more agnostic view of change on Wikipedia over time, saying in 2006, “One of the great things about NPOV is that it is a term of art and a community fills it with meaning over time” (Reason 2006).

Fourth, Wikipedia has a unique availability of data. A major problem in most case-specific accounts of institutional change is the inaccessibility of comprehensive data to evaluate causes and effects. Scholars must rely on a sliver of data that are available to piece together what the preferences of various actors might be, what actions these actors took, and how the preferences and actions of these actors led to institutional change or stability. What adds to the problem is that the publicly available data may fail to reflect the actual processes that led to change. For example, debates may take place in front of cameras and voting may be logged into records, but the meaningful negotiations occur behind closed doors.

In comparison with other institutions, Wikipedia has several advantages in terms of studying institutional change. In other largescale institutions, it is not feasible to identify and collect data on every participant, and to track the behavior of every participant over time. Scholars are often forced to fill gaps with theory or by making assumptions. There is a risk that unobserved variables have a significant impact on outcomes, which makes it hard to make robust claims about the causes of institutional change. On Wikipedia, on the other hand, virtually all edits and comments are logged and open to public viewing. This means that it is possible to trace each input in every debate, as well as to sift through the editing history of each Wikipedia editor. Thus, there is an enormity of relevant data on which to test, refine, and build theories of institutional change.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The research design of the paper has two components. First, the paper codes content in the lead of Wikipedia articles, showing a pro-to-anti-fringe shift in content. Second, the paper does process-tracing of trends within Wikipedia’s governance to show how this shift happened (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). In terms of analyzing changes in the content of Wikipedia articles, the paper uses nonautomated qualitative content analysis to classify whether Wikipedia pages use language that legitimizes or delegitimizes fringe positions and entities. An advantage of qualitative content analysis is that it permits analysts to observe subtle, yet meaningful nuances in meaning.Footnote 17 It entails human coding and interpretation of textual sources according to structured and systematic coding schemes (see Boreus and Bergström Reference Boreus and Bergström2017; Elkins, Spitzer, and Tallberg Reference Elkins, Spitzer and Tallberg2021; Herrera and Braumoeller Reference Herrera and Braumoeller2004). More specifically, the paper systematically classified a sample of 63 article leads with a predetermined coding scheme.Footnote 18 The 63 pages were chosen because they are representative of the population of relevant cases: all the pages are on topics that have been linked to pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, extremism, and fringe rhetoric in public discourse.

Within the relevant population, the chosen pages reflect diverse topic areas (health, climate, gender, sexuality, race, abortion, religion, politics, international relations, and history). The pages also vary in terms of the time of creation (some pages were created early and others later), and temporal prominence (the topics covered in the pages were more prominent during different time periods). The pages include biographies (which have more restrictive standards for inclusion of pejorative content) and nonbiographies.

The contents of the chosen Wikipedia pages were classified according to a five-category coding scheme. These categories reflect varying degrees of neutrality. On one end of the spectrum, the language lends credence and legitimacy to fringe views. On the other end, the language firmly delegitimizes the fringe views:

-

1. Fringe normalization: The fringe position/entity is normalized and legitimized. There is an absence of criticism.

-

2. Teach the controversy: The fringe position/entity is presented as a matter of active scientific or political dispute (A says X, B says Y).

-

3. False balance: The lead places emphasis on the expertise, credibility, evidence, and arguments of the anti-fringe side (e.g., “some scientists say,” “some medical organizations say”), but the pro-fringe side still gets space to rebut.

-

4. Identification of the fringe view: The lead places emphasis on the legitimacy and the overwhelming numbers that compose the anti-fringe side (e.g., “scientific consensus,” “the scientific community”), but space is still given to the pro-fringe side.

-

5. Proactive fringe-busting: Space is only given to the anti-fringe side whose position is stated as fact in Wikipedia’s own voice.Footnote 19 The evidence that supports the anti-fringe position is presented, whereas the flaws of the pro-fringe perspective are outlined.

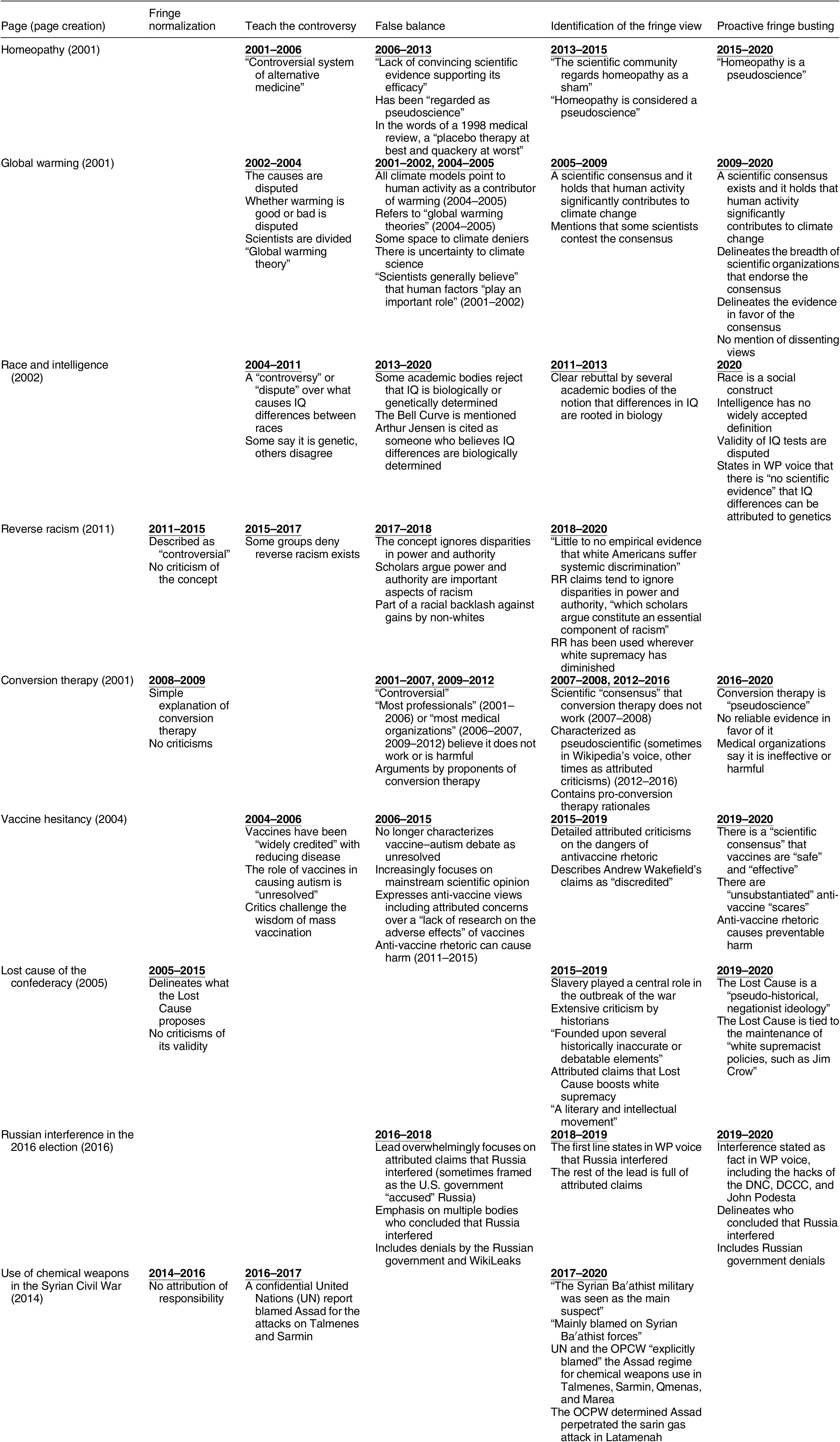

The paper uses a cross-temporal analysis of each article’s lead, thus tracking changes over time. A stable version of each article was analyzed at the end of each year. Articles were checked more frequently if the pages had frequent and erratic editing patterns. Changes on Wikipedia articles can be accessed through archives that show each change, thus making the study replicable. Table 1 and the Supplementary Material include examples of language from each article’s lead. Due to space constraints, changes in nine representative article leads are shown in Table 1, whereas 54 additional articles are in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1. The Lead to Controversial Science- and Politics-Related Wikipedia Pages, January 2001 to June 2020

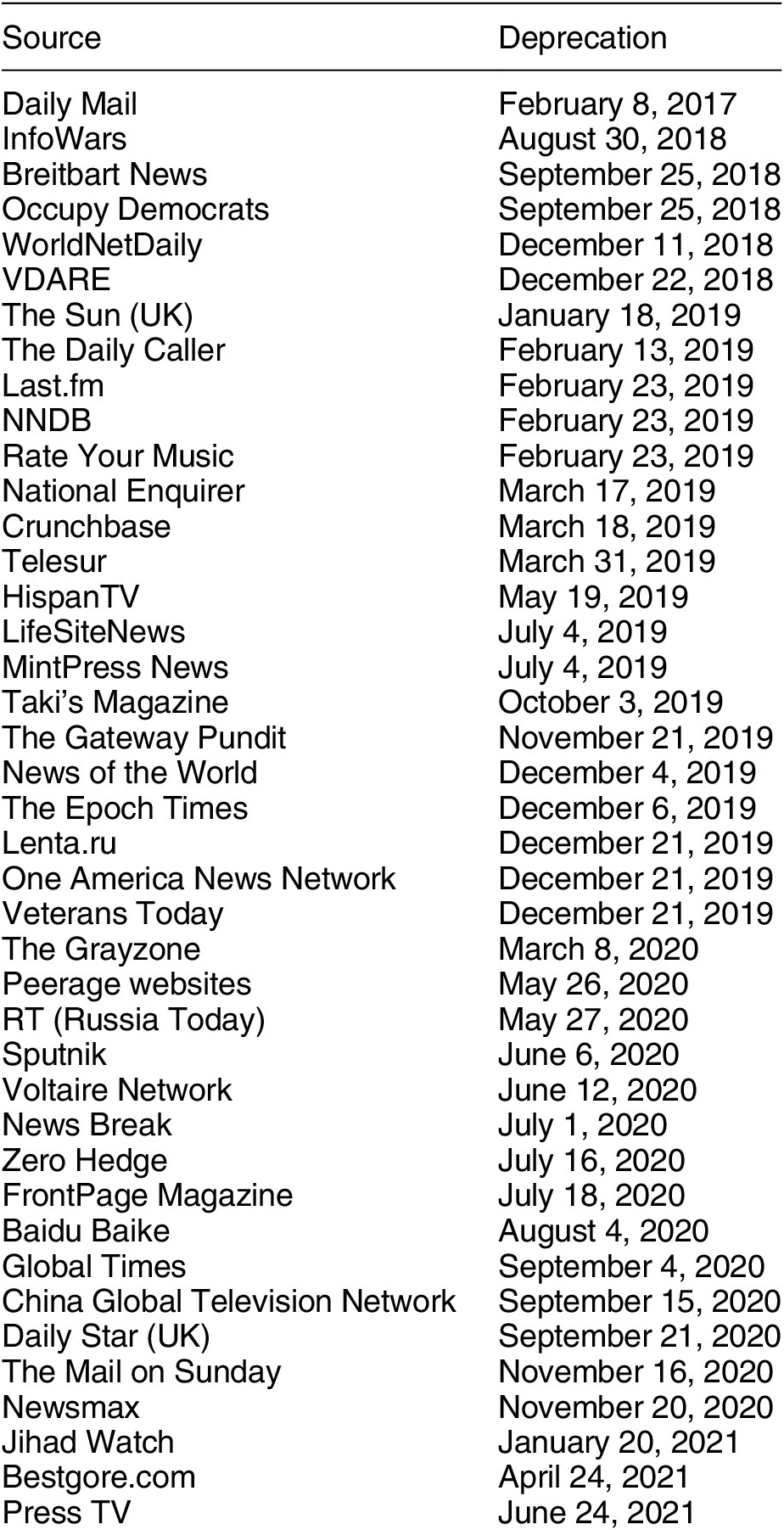

Table 2. Wikipedia’s List of Deprecated Websites, as of September 4, 2021Footnote 23

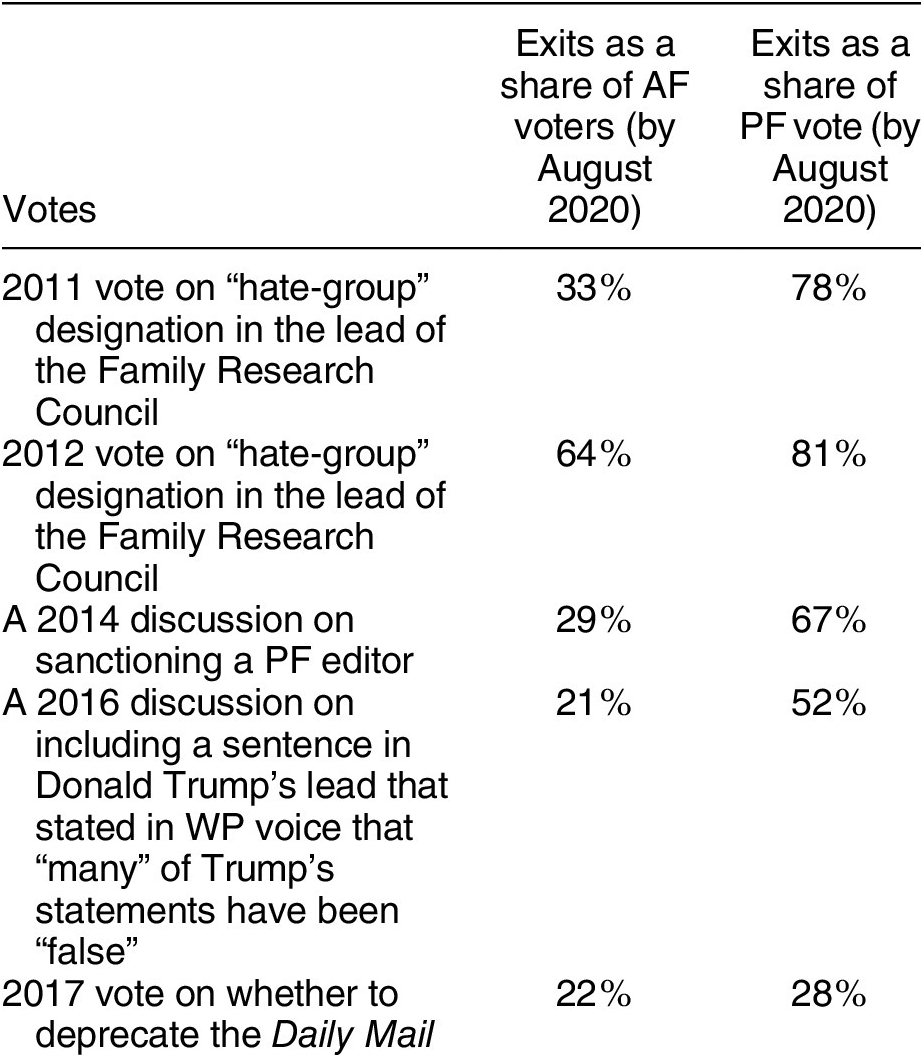

Table 3. Referenda and Subsequent Exits

Per the analysis (see Table 1 and the Supplementary Material), content on the English Wikipedia shows a clear trend from language that legitimizes fringe positions to language that delegitimizes fringe positions. Newer articles tend to adopt language from the anti-fringe categories at their creation, whereas older articles tend to adopt language that is more fringe-normalizing at their creation. None of the articles move in a direction where they become more fringe-normalizing.

The analysis shows that in its early years, the English Wikipedia adhered to a “strict” NPOV approach whereby Wikipedia content was open to a diversity of opinions and sources, and where Wikipedians could not state contested views as facts in Wikipedia’s own voice. Thus, a typical page on a subject related to pseudoscience and contested science would adopt a “Some say X, others say Y” style, even on topics where mainstream scientific opinion overwhelmingly favored X.

ENDOGENOUS CHANGE ON WIKIPEDIA

Explaining the Findings

The paper has demonstrated that English Wikipedia content changed over time. This section seeks to explain why the content changed. In doing so, the paper uses process tracing. The paper systematically analyzes the internal Wikipedia discussion forums where editors duked out content. More specially, the paper analyzes the archived talk pages of the 63 articles and relevant discussions about article content on general noticeboards.Footnote 20 To classify editors into the Anti-Fringe camp (AF) and the Pro-Fringe camp (PF), the paper uses a variety of data sources: the viewpoints expressed by editors on the article talk pages themselves, the views expressed by editors brought up for sanctioning on the Administrators’ noticeboard or the “Requests for Enforcement” page before the Arbitration Committee, and lists of editors brought up in arbitration committee rulings.

These data sources provide article-by-article evidence about relevant individual editors on the pages in question. However, to assess systematically what happens to AF and PF editors across the English Wikipedia (not just the 63 articles), the paper uses a sample of referenda where editors are implicitly asked whether they support a pro- or anti-fringe interpretation of the NPOV guideline. The user histories of the participants in the referenda are then analyzed to uncover whether they are still active or whether they have voluntarily left Wikipedia, substantially reduced their number of contributions, been banned from the relevant topics, or blocked from Wikipedia in its entirety.

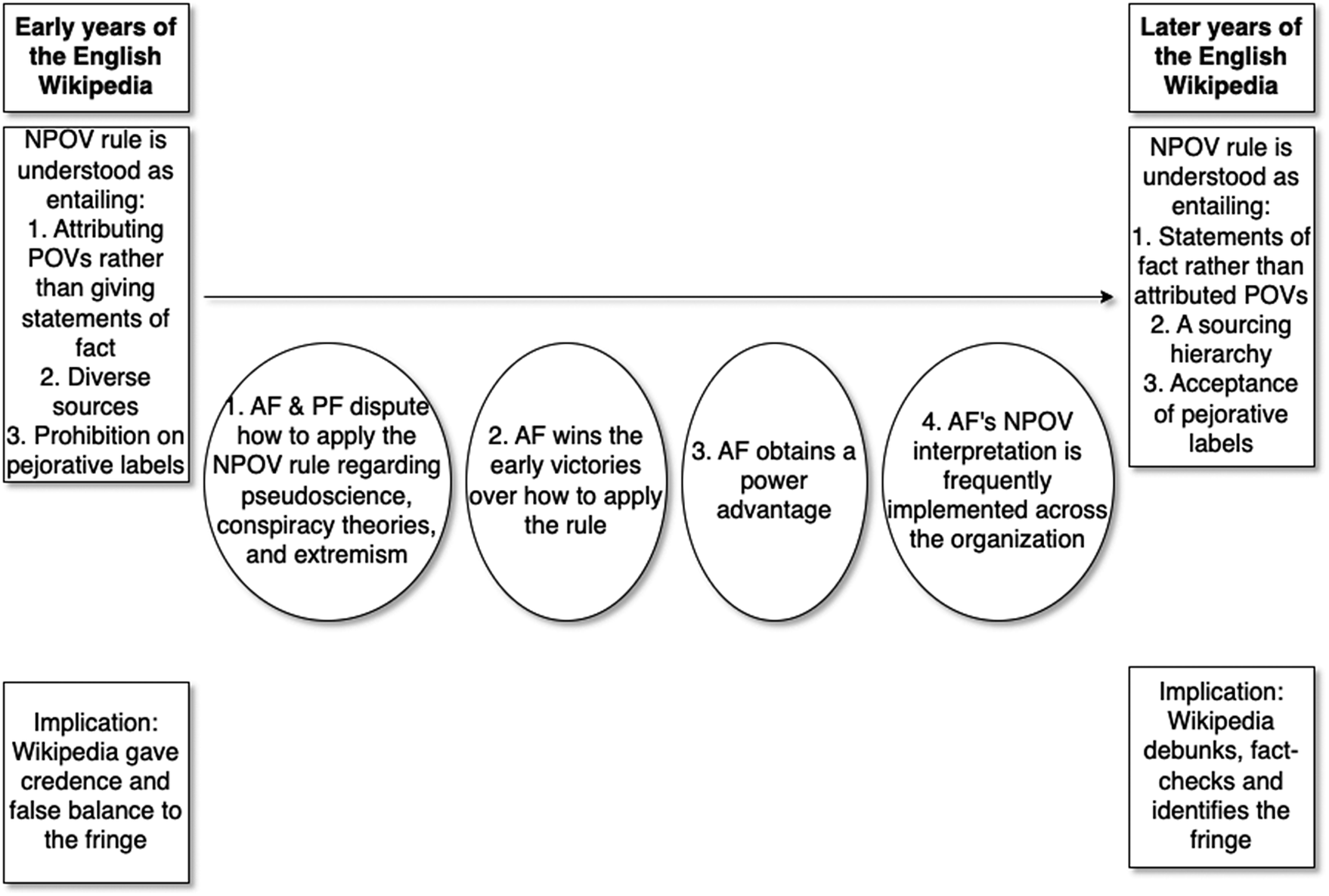

The evidence is broadly consistent with the observable implications of the paper’s theory of endogenous institutional change (the processes of the theory are outlined in Figure 2).Footnote 21

Figure 2. How Did the NPOV Rule Change?

The key piece of evidence is that PF members disappear over time in the wake of losses, both voluntarily and involuntarily. PF members are those who vote affirmatively for policies that normalize or lend credence to fringe viewpoints, who edit such content into articles, and who vote to defend fellow members of PF when there are debates as to whether they engaged in wrongdoing. Members of AF do the opposite.

The causal mechanism for the gradual disappearance is that early losses demotivated members from PF or led to their sanctioning, whereas members of AF were empowered by early victories. As exits of PF members mount across the encyclopedia, the community increasingly adopts AF’s viewpoints as the way that the NPOV guideline should be understood.

Step 1: Rule Ambiguity

The NPOV rule of Wikipedia is ambiguous in its specific application. During the early period of Wikipedia, Wikipedia’s NPOV rule was understood as indicating a “describe-the-controversy” approach to disputes between sources: Wikipedia should not take sides on contested issues, and Wikipedia should be open to a diverse array of sources. Thus, the policy allowed for inclusion of lower-quality sources, so long as they were attributed. This meant that if sources disagreed in terms of how they covered the topic of homeopathy, the Wikipedia article on homeopathy would present both sides of the issue and avoid taking a firm stance. The Wikipedia page on homeopathy included text that effectively said “Advocates for homeopathy say…” and “Critics of homeopathy say…,” whereas it was frowned upon among early Wikipedians to state decisively in Wikipedia’s own voice that “Homeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine” (as the first line of the Wikipedia page stated in 2020). This was largely in line with Larry Sanger’s intentions when he crafted the NPOV rule (ArsTechnica 2014).

Step 2: Clashes between Camps over Rule Interpretations

On contentious topics (e.g., American politics, conspiracy theories, and pseudoscience), editors had vast differences in terms of how they understood the application of Wikipedia’s rules. Editors who were anti-conspiracy theories, anti-pseudoscience, and liberal (the AF camp) pushed understandings of NPOV that took a firm anti-conspiracy-theory and anti-pseudoscience stance. Thus, they argued for reliance on strong sources (such as studies and highly reputable mainstream news outlets), nonuse of lower-quality sources (such as partisan outlets and disreputable outlets), stating claims from strong sources in Wikipedia’s own voice (rather than attributing them as a source’s opinion), firmly stating that minority views are fringe, and stating that falsehoods are falsehoods.

Editors who were more supportive of conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and conservatism (the PF camp) argued for reliance on sources across a broad range of reliability (in part, because they perceived academics and newspapers of record to be biased), stating claims from sources as if they were always an attributed POV, and avoiding firm stances on the state of a controversy.

On the homeopathy page, this meant that PF members raised questions about relying on reporting by the New York Times and Washington Post, insisted that studies skeptical of homeopathy’s efficacy be phrased as opinion, and sought to include rebuttals by pro-homeopathy organizations and pseudoscientists. AF members held the opposite view, as they sought to phrase skeptical content in Wikipedia’s own voice and strongly opposed content sourced to pro-homeopathy organizations.

Step 3: Formation of a Power Asymmetry

Over the course of years, AF successfully shaped how to understand the practical application of Wikipedia’s NPOV guideline. These early victories gave AF an upper hand in editing disputes on pages related to conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and American politics. There was no single critical juncture. Rather, there were many gradual mutually reinforcing steps across several spheres of Wikipedia.

One type of change that was important early in Wikipedia’s development was intervention into content disputes by arbitrators on highly dysfunctional pages. Highly dysfunctional pages are those characterized by edit-warring among a multitude of editors to the point that the pages are unstable over extended periods of time, and editors cannot even agree on the status quo version of the pages.

Two particularly important early arbitration rulings in the early years were the arbitration committee cases on climate change (2005) and pseudoscience (2006), which largely reaffirmed some viewpoints held by AF in those specific disputes and led to sanctions that primarily targeted prolific PF editors (although some AF editors were also targeted) for behavioral wrongdoing. The disputes were at their core about edit-warring between different camps as to whether climate change articles should reflect the scientific consensus on climate change or lend weight to those who dispute the scientific consensus, and broadly about how pseudoscientific ideas and minority scientific perspectives should be framed.

A second type of important changes involve the writing of guidelines to supplement the existing NPOV guideline and clarify how the NPOV guideline should be applied. This includes the creation of the Reliable Sources guideline (2005), which introduced a basic framework for evaluating the reliability of sources, the Fringe Theory guideline (2007), which introduced a basic framework for evaluating minority views and fringe views, and the Reliable Sources (Medicine) guideline (2008), which set a higher quality threshold for sources on medicine-related topics out of a concern that poorly sourced content could cause harm to readers.

These guidelines were crafted by a relatively small set of experienced editors, including many from AF who were involved in active content disputes on topics that related to these rules. All editors can participate in processes to change rules and add supplements to rules. These changes must go through the normal Wikipedia consensus decision-making process. While these particular rules were not written to specifically address content in those disputes, the enactment of these rules as supplemental modifications to the NPOV guideline would prove useful in those disputes. Furthermore, discussions related to those rules showed that editors wanted to privilege science and academic expertise in terms of identifying what is fringe, but the Reliable Sources and Fringe Theory guidelines were broad enough in scope that they could also be used to identify fringe discourse and beliefs outside of science, such as with conspiracy theories and extremist rhetoric in politics.

Step 4: Reinterpretation of Wikipedia’s Rules

The early victories and selective departures had positive feedback effects for three reasons: (i) they enhanced the value of experience, (ii) they created a numerical advantage, and (iii) they spurred a sourcing bias. Consequently, AF editors experienced greater success in editing, whereas PF editors did not, which led to lopsided exits over time. Together, these factors led AF to increasingly get what it wanted and sway the broader Wikipedia userbase to see one interpretation of the rules as the undisputed accurate interpretation of the rules.

First, experience matters a great deal on Wikipedia, which makes disproportionate exits early on highly consequential. Since Wikipedia is notoriously complicated for new editors to maneuver, experienced editors have a decisive advantage in content disputes (Jemielniak Reference Jemielniak2014). Experience helps in understanding the rules, norms, and processes of Wikipedia. This leads to greater success in content disputes and edit wars, as well as makes experienced editors able to drive disruptive “newcomers” away from Wikipedia and instill in newcomers’ certain understandings of how rules should be interpreted. Experience also raises the likelihood of becoming an administrator, thereby gaining the power to enforce the rules and sanction editors.Footnote 22 Additionally, experience increases the likelihood of participation in general noticeboard discussions where sanctions of individual editors and specific rule interpretations are discussed in detail. Experienced editors also become aware of administrator elections and arbitration committee elections, which are important levers of power on Wikipedia.

Second, there is power in numbers. It is easier for PF members to fall afoul of the rules if they are frequently at a numerical disadvantage in editing disputes. It makes them less likely to win content disputes (which are often determined by numbers), forces them to spend more time to advance their views, and makes them more likely to have to edit war (make frequent reverts of AF editors). Whereas multiple AF editors can share the burden of doing reverts of PF’s edits and not violate any edit-warring restrictions, a PF editor may be forced to do multiple reverts, thus risking sanction.

Third, the gradual development of a sourcing hierarchy—whereby some sources were deemed reliable, and others were deemed unreliable—created advantages for AF editors. The culmination of a long, gradual conflict over the use of sources on Wikipedia was the 2017 vote to deprecate (ban) the Daily Mail, a British tabloid, from being used as a source for statements of fact. Over the next 4 years, 38 additional sources were deprecated.

The gradual development of the sourcing hierarchy reflects how the Wikipedia community shifted its understanding of reliability over time, facilitated by the experience and numerical advantage of AF. An examination of pages in the early years of Wikipedia shows that Wikipedians had very lax standards for sourcing. By the mid-2000s, momentum had formed to privilege scientific publications. This did not mean that other sources were unusable, but that priority and prominence should be afforded to scientific publications. During these early years, Wikipedians did not appear to distinguish between news sources in terms of reliability in any clear manner. Articles into the 2010s show considerable usage of sources that would ultimately by the mid-2010s be deemed unreliable, including sources that were deprecated from 2017 onward.Footnote 24 Discussions about these sources in the previous years had not concluded with support to prohibit them, demonstrating a change in how the community looked at them. The key difference is that the ranks of PF editors who blocked previous attempts to ban sources had been thinned out considerably by 2017.

This hierarchy of sources has implications both for what kind of content can be added to Wikipedia and how it will be phrased. For example, if the New York Times (a source that Wikipedia editors came to recognize as highly reliable) describes something as a conspiracy theory, whereas the New York Post (a source that Wikipedia editors have determined to be unreliable) differs from that description, then Wikipedia content can be added that firmly states in Wikipedia’s voice that something is a conspiracy theory. Under a previous collective understanding of Wikipedia’s rules, Wikipedia’s content would not give a firm statement in Wikipedia’s voice but would rather attribute particular claims to the Times and attribute rebuttal claims to the Post. Thus, over time, Wikipedia has accepted the use of contested labels and taken sides on contested subjects, ultimately producing a type of content that is distinctly anti-pseudoscience and anti-conspiracy theories, and which has the perception of a liberal bent in U.S. politics.

Each shift in policy further weakened the position of PF in editing disputes and made the editing experience less rewarding for those editors because they ended up on the losing end of content disputes. Over time, PF editors responded in three waysFootnote 25:

-

1. Fight back: By increasingly editing against consensus and in violation of new interpretations of Wikipedia policy. These editors were subsequently banned.

-

2. Withdraw: By leaving Wikipedia or reducing their contributions.

-

3. Acquiesce: By gradually adapting to the new interpretations of Wikipedia policy.

Article-by-article evidence substantiates these patterns, with prominent PF editors getting banned, retiring, or adjusting to new interpretations of Wikipedia guidelines.Footnote 26 In explaining their departure on their talk page, retired PF editors frequently decried what they perceived as Wikipedia’s increased bias, hostile editing environment, and the pointlessness of fighting against what they described as a cabal.Footnote 27 This stands in contrast to the explanations offered by non-PF members for retiring. Some PF editors proved more flexible to Wikipedia’s changing environment, acquiescing to new interpretations of Wikipedia policy. For example, a PF editor might affirm the new standards in Wikipedia’s sourcing policy by insisting that content from a source like the New York Times should be stated in Wikipedia’s own voice when a Times story criticizes a left-leaning politician or left-leaning cause. However, in doing so, those PF editors help enshrine the emerging new interpretations of Wikipedia guidelines.

In addition to article-by-article evidence of departures of Wikipedia editors, the paper uses a sample of hotly contested referenda (where editors are asked to express their views about the NPOV rule’s application to fringe topics) to gage whether the disappearance of PF editors (measured by their support or opposition for a fringe position) is systemic across the encyclopedia. This is a unique and useful data source that shows that the relative disappearance of PF editors is systemic.

The raw numbers undersell the importance of those who have departed the encyclopedia. Many of the departees were highly prolific experienced editors from PF, whereas many of the editors who sided with AF and disappeared over time were not highly prolific editors in the first place. These disproportionate exits meant that over time, understandings in line with AF’s interpretation of Wikipedia policy become taken for granted as the way the rules should be interpreted, causing gradual institutional changes that amount to a drastic institutional change over a nearly 20-year period.

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS

This paper has sought to explain why content on the English Wikipedia transformed drastically over time. The explanation hinges on endogenous factors related to early victories, feedback effects, and population loss. In this section, the paper examines two key alternative explanations, finding that they are inapplicable and generally inconsistent with the data (three additional alternative explanations are addressed in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 28

External Events and Processes

One alternative hypothesis is that external events caused ideational change among Wikipedians. For example, Donald Trump’s 2016 election, the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the emergence of “fake news” websites may have caused Wikipedians to re-evaluate how they understand the rules of Wikipedia and the role of Wikipedia in society. However, as the paper documented, the transformation on Wikipedia has been gradual over time, preceding prominent shocks from 2016. Furthermore, the emergence of “fake news” websites does not fit neatly with Wikipedians’ decision to deprecate long-standing traditional news sources, such as the Daily Mail. The events of 2015 and 2016 did not bring source reliability to the fore in a new way on Wikipedia. Rather, Wikipedians had intensely debated the reliability of sources for nearly a decade prior. It took Wikipedians until 2017 to start deprecating sources because the editors that previously vetoed such attempts were no longer active on the encyclopedia.Footnote 29

Another version of this hypothesis is that slow exogenous processes led Wikipedians to re-evaluate their own attitudes toward the guidelines. For example, Wikipedians may have increasingly come to hold more pro-LGBT views, stronger anti-racism views, and pro-science attitudes. While attitudinal change can certainly be documented among certain Wikipedians, they have remained very stable among many of those belonging to AF and PF, as they vote consistently for and against certain items in predictable ways over long time periods. If a disproportionate number of PF editors had not disappeared over time, they would have been able to block drastic changes.

A third version of this hypothesis is that the sources that Wikipedia relies on for content changed how they cover pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and extremism. In other words, the news media and the scientific community changed, not Wikipedia. While it is true that Wikipedia is necessarily a reflection of what sources say, it is not correct that news sources and studies have uniformly moved in the same direction on all the subject matters listed in Table 1 and the Supplementary Material. Even on subject matters where coverage has changed, such as climate change, climate change denial sources have changed tactics in how they argue against climate change. Rather than deny that any warming has occurred, they dispute the precise role of human activity, emphasize how “alarmist” mainstream climate scientists are, and highlight events that purportedly contradict the scientific consensus. Rather than reflect these updates to climate change denialism in mainstream sources, Wikipedians have simply excluded or debunked climate change denial rhetoric in articles. Furthermore, the particular sources that continued to promote pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and extremism were over time ultimately deemed unreliable on Wikipedia.

Influx of New Editors

Anyone can create a Wikipedia account and edit. It is therefore reasonable to query whether Wikipedia experienced an influx of new editors with new ideas, thus causing the transformation over time. This would mean that the old guard of Wikipedia editors were simply replaced or outmaneuvered by a new breed of editors. There are several reasons why this is unlikely to have caused the transformation. Wikipedia has a very rigid and complex structure of rules and norms. New editors that edit in ways that older editors disapprove of often find themselves in trouble. As highlighted above, experience is a source of power of Wikipedia that makes it easier for the old guard to shape the encyclopedia, both by sanctioning disruptive newcomers and by indoctrinating newcomers into a “correct” way of editing. Newcomers, therefore, find themselves forced to assimilate or be booted off the platform. It is also unlikely that the later generation of Wikipedia editors tended to be more likely to be experts and predisposed to mainstream science than the first movers on Wikipedia. Judging by self-described descriptions of themselves, many of the earliest Wikipedians were scientists or had advanced degrees, in particular among editors on pages related to pseudoscience.

CONCLUSION

Since its inception in 2001, Wikipedia has transformed from an encyclopedia that adopted a strict “teach the controversy” approach (whereby a diversity of opinions and sources were reflected in articles) to one where Wikipedia takes firm sides on contested subjects. Whereas Wikipedia used to normalize and lend credence to pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and fringe rhetoric, it has over time become firmly anti-pseudoscience and anti-conspiracy theories.

This transformation occurred through endogenous processes that were ultimately rooted in rule ambiguity, early dispute outcomes, and population loss. The resolution of early disputes in several areas of the encyclopedia demobilized certain types of editors (while mobilizing others) and strengthened certain understandings of Wikipedia’s ambiguous rules (while weakening other understandings of Wikipedia rules). Change occurred endogenously and gradually, as shared meanings from within Wikipedia’s collective about the rules got altered through a combination of compulsory power (sanctioning of dissenters by elite actors) and productive power (collective delegitimization of certain rule interpretations).

This explanation for institutional change on Wikipedia can plausibly help to explain institutional change in other contexts. We might observe in other institutions that institutional change happens as losers become demotivated and sanctioned, and winners become motivated and rewarded. For example, career bureaucrats might leave public service when the bureaucracy shifts toward policies that they disagree with. The bureaucrats could stay in the bureaucracy and make it harder for opponents to transform the bureaucracy, but they might instead leave the bureaucracy because they find it demotivating to fight uphill against other bureaucrats. Rather than obstruct change, the population loss of dissident bureaucrats can propel change.

Within political movements and parties, we can also see how establishment figures who are out of step with newly dominant ideas choose voluntarily to retire rather than obstruct change within the movement. This can plausibly be seen in the Republican Party, as Trump critics have opted to retire rather than use their position to steer the movement in a direction that they find more palatable. Similarly, victories for one side within a movement may energize winners and encourage like-minded actors to jump on the bandwagon in support of that side. This may help to explain how the Tea Party cemented its control of the Republican Party (Blum Reference Blum2020). It may also help to explain how the conservative legal movement gradually accepted the legal theory behind the unconstitutionality of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was considered fringe and weak in 2010, but grew in support as conservative justices in lower courts ruled the ACA unconstitutional, ultimately almost leading the Supreme Court to rule that the ACA was unconstitutional in 2012 (a narrow 5-4 decision upheld the law while hobbling aspects of it). It may also explain why certain police department cultures form, as some police are driven out of the organization, while others get boosted. It has also been posited that the stability and strength of illiberal regimes within the European Union have gradually been strengthened as dissatisfied citizens migrate from authoritarian states to liberal states (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020). However, more research is needed to assess the generalizability of this endogenous mechanism for institutional change.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000138.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the American Political Science Review Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JZLTQR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for elaborate feedback from Martha Finnemore and Henry Farrell on earlier versions of the manuscript. This article also benefited from comments by Bit Meehan, Eric Grynaviski, Kendrick Kuo, Michael Miller, Natalie Thompson, Yonatan Lupu, participants at the GWU Political Science Department Graduate Caucus workshop, and three anonymous reviewers in the GWU Political Science Department, as well as the editors and four anonymous reviewers at the APSR.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author affirms this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.