Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

This article, drawing on recent studies of class consciousness and powerlessness explained in individual versus system level terms, develops and analyzes an operational measure of “power consciousness.” Power consciousness is defined as a person's evaluation of his or her political power position and his or her explanation of the causes of any inadequacies or advantages perceived in this position. The operational measure of power consciousness arrays responses to two items on political power satisfaction (one of them open-ended) along a dimension which ranges from satisfaction, to dissatisfaction ascribed to personal failures of the respondent, to dissatisfaction explained in terms of problems with the political system. Survey data are utilized for a comparative analysis of whites' and blacks' scores on the power consciousness measure. The following topics receive detailed attention: the place of power consciousness in the matrix of power measures; its relationship to background factors, especially level of education; its relationship to indicators of political discontent; and the impact of power consciousness on levels and styles of political behavior. The analysis is followed by suggestions for the development of future work in this area.

This is a revised version of a paper prepared for delivery at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association in New Orleans, September, 1973. I am grateful for financial support from the National Science Foundation and the Social Science Research Council. Douglas B. Neal and Nancy Brussolo did outstanding jobs coding the power consciousness variable and Doug Neal also provided indispensable aid in the data analysis. My thanks to George Balch, Steven Coombs, Edie N. Goldenberg, and Robert Putnam for their helpful comments, and to Jack Walker for his very thorough suggestions for revision of the original version of the manuscript.

1 There is a substantial amount of research reported in the literature. See Prewitt, Kenneth, “Political Efficacy,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. Sills, David L. (New York: Crowell, Collier, and Macmillan, 1968), Vol. 12, pp. 225–28Google Scholar, for a concise review and bibliography.

2 Easton, David and Dennis, Jack, “The Child's Acquisition of Regime Norms: Political Efficacy.” American Political Science Review, 61 (03 1967), 38 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

3 See, for example, Balch, George I., “Multiple Indicators in Survey Research: The Concept ‘Sense of Political Efficacy’” Political Methodology, 1 (Spring 1974), 1–43 Google Scholar; Converse, Philip E., “Change in the American Electorate,” in The Human Meaning of Social Change, ed. Campbell, Angus and Converse, Philip E. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1972), pp. 334–37Google Scholar; and Muller, Edward N., “Cross-National Dimensions of Political Competence,” American Political Science Review, 64 (09 1970), 792–809 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 Converse, , “Change in the American Electorate,” p. 334 Google Scholar.

5 Balch, , “Multiple Indicators in Survey Research,” p. 31 Google Scholar.

6 These definitions are drawn from the critique of the relevant literature found in Fishbein, Martin, “A Consideration of Beliefs, and Their Role in Attitude Measurement,” in Readings in Attitude Theory and Measurement, ed. Fishbein, Martin (New York: John Wiley, 1967), pp. 256–66Google Scholar.

7 Seeman, Melvin, “On the Meaning of Alienation,” American Sociological Review, 24 (12 1959), 784 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

8 Seeman, Melvin, “Alienation and Engagement,” in The Human Meaning, pp. 510–11Google Scholar. See also ibid.

9 Clark, John P., “Measuring Alienation Within a Social System,” American Sociological Review, 24 (12 1959), 849–52CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Robinson, John P. and Shaver, Phillip R., Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes, Appendix B (Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, 1969), pp. 209–10Google Scholar.

10 A good case can be drawn from Fishbein's “A Consideration of Beliefs” for an approach which explicitly includes an evaluative component. He argues, in brief, that “all beliefs about an object carry some implicit or explicit evaluation of the attitude object” (p. 264). The problem is that “the same belief may have totally different attitudinal significance for different individuals” (p. 263). Therefore, “independent measures of the evaluative aspects of beliefs” (p. 265) should be utilized.

Following the logic of this argument, the power consciousness indicator developed in this paper measures each individual's power satisfaction in an explicit manner. In the section below on “The Place of Power Consciousness in the Matrix of Power Measures” I will examine the relationship between familiar cognitive indicators of subjective powerlessness and power consciousness.

11 Lane, Robert E. defines general political consciousness as the answer to this question in Political Thinking and Consciousness (Chicago: Markham, 1969), p. 319 Google Scholar.

12 Portes, Alejandro, “On the Interpretation of Class Consciousness,” American Journal of Sociology, 77 (09 1971), 228 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See also Ollman, Bertell, “Marx's Use of ‘Class’,” American Journal of Sociology, 73 (03 1968), 573–80CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Lipset, Seymour M., “Social Class,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 15, pp. 296–315 Google Scholar, for reviews of the literature. A somewhat different view is found in Lukacs, Georg, History and Class Consciousness (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1971)Google Scholar, who defines class consciousness, p. 73, as “the sense, become conscious, of the historical role of the class.” The reader should examine pp. 46–82, “Class Consciousness,” at a minimum.

13 Explanations of satisfactory power situations were not secured from respondents in the study reported here.

14 Gurin, Patricia, Gurin, Gerald, Lao, Rosina C., and Beattie, Muriel, “Internal-External Control in the Motivational Dynamics of Negro Youth” Journal of Social Issues, 25 (Summer 1969), 45 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15 Ibid., p. 52. As Gurin et al. say (p. 33): “Instead of depressing motivation, focusing on external forces may be motivationally healthy if it results from assessing one's chances for success against systematic and real external obstacles rather than the exigencies of an overwhelming, unpredictable fate.” See also Forward, John R. and Williams, Jay R., “Internal-External Control and Black Militancy,” Journal of Social issues, 26 (Winter 1970), 75–92 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

16 For a complete description of the sampling procedure, see Aberbach, Joel D. and Walker, Jack L., Race in the City (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973), pp. 245–52Google Scholar. Aside from the city of Detroit, the areas covered by the directory were Hamtramck, Highland Park, the Grosse Pointes, and Harper Woods.

17 A follow-up question was asked only of those who felt they had too little power because of my fear that a probe of the answer “the right amount of power” would appear to challenge that response, damage the rapport between interviewer and interviewee, and bias other responses. The spontaneous comments given to our interviewers, however, and a follow-up question asked of those saying “right amount” on a survey administered to a small sample in Detroit, lead me to believe that these dangers are minimal. The question on the small Detroit study, incidentally, yielded answers focusing mainly on the existence of the franchise, other possibilities for participation, and general system satisfaction. My thanks to Professor Monica Blumenthal of the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan for placing the item on her questionnaire.

18 Converse, , “Change in the American Electorate,” p. 335 Google Scholar.

19 While the phrase “people like you” was not used in the follow-up question, most people seemed to keep it as their frame of reference in answering.

20 Fifty-nine percent of the white panel respondents and 46 percent of the black panel respondents felt they had the right amount of power. More important, the distributions of reasons given for the power dissatisfaction were remarkably congruent between each racial panel and the appropriate cross-section, especially when one takes into account the slight bias to a more highly educated group found in the panel due to the greater attrition of lower as opposed to higher education respondents.

21 It is likely that these percentages have dropped since 1971 when the data were collected, but in 1966 when the same question was asked on the SRC Election Study, 55 percent of the whites and 60 percent of the blacks living in the central cities of the 12 largest SMSA's said they had the right amount of power.

22 There was total agreement between the first and second codings for 82 percent of the answers by whites and 79 percent of the answers by blacks. Most of the disagreements (12 percent for whites and 15 percent for blacks) were about the order of the appropriate codes (i.e., what should be coded as the primary response and what as the secondary response), not the meaning itself. In only 6 percent of the cases for each race was there complete disagreement about the meaning of a response, and these disagreements, were well spread out among the code categories.

23 Whites also comprise the small percentage of respondents who say, to quote one of our respondents, “my one vote doesn't mean much.”

24 Without going into detail, the small number of respondents in the group weakness category who were not concerned with race mentioned a variety of groups. For example: “people like me–the minority better educated group–[who] have little influence over the majority group.”

25 Richard Austin ran for mayor of Detroit in 1969 and lost by a very slim margin. He ran successfully for Michigan secretary of state in 1970 and is now the highest ranking black state office holder.

26 The small number of people coded under isolated individuals in the category “one vote alone doesn't count” were not coded here or under 4.f. because their responses did not clearly indicate that the political system itself was at fault. It is possible that they believe this is so, but it seemed a more conservative convention to assume that they see themselves as isolated, symbolize this isolation in terms of the vote, and do not blame the situation on some problem with the political system.

27 Seeman, , “Alienation and Engagement,” p. 472 Google Scholar.

28 Muller, pp. 794–801. The following questions were asked in deriving the “Ability to Influence Government” index:

1. Suppose a law were being considered by the Congress in Washington that you considered very unjust or harmful. What do you think you could do about it?

la. If you made an effort to change this law, how likely is it that you would succeed: very likely, somewhat likely, or not very likely?

2. Suppose a law were being considered by the [name of local government unit] Common Council that you considered very unjust or harmful. What do you think you could do about it?

2a. If you made an effort to change this law, how likely is it that you would succeed: very likely, somewhat likely, or not very likely?

29 The item is worded as follows: How much political power do you think people like you have? A great deal, some, not very much, or none?

30 Gamma is used because it is a widely known and understood ordinal measure of association. It is highly sensitive, however, and can distort when there are extreme marginals. Therefore, the tables used to calculate the Gamma coefficients were checked for each coefficient reported in the article in order to guard against unreliable results.

31

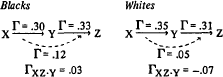

If one specifies that X→ Y→Z is correct, then one would predict that ![]() . The relevant data for blacks and whites are as follows:

. The relevant data for blacks and whites are as follows:

32 That power satisfaction or dissatisfaction is basically the end-product of perceived ability to influence government rather than the. other way around seems logical enough, although there are grounds for arguing the other way. See Muller, pp. 801–02.

33 Prewitt, p. 226.

34 Education is not atypical of the SES variables in the Detroit study. Occupation and income are similarly related to power consciousness.

35 This reinforces a picture of discontent among upper status blacks found in other analyses of the data from the Detroit study. See Aberbach and Walker, esp. pp. 118–21, 158–61, and 185–86.

36 Lane, Robert E., Political ideology (New York: Free Press, 1962), p. 143 Google Scholar. See also Sennett, Richard and Cobb, Jonathan, The Hidden Injuries of Class (New York: Knopf, 1972)Google Scholar.

37 This view is also prevalent in whites' notions about the sources of the deprivations blacks experienee in American society. See Campbell, Angus and Schulman, Howard, Racial Attitudes in Fifteen American Cities: A Preliminary Report Prepared for the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, 1968), pp. 30–31 Google Scholar.

38 Katznelson, Ira, Black Men, White Cities (New York: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Race Relations, 1973), pp. 199–200 Google Scholar.

39 Forward and Williams, p. 88. See also Gurin et al. for the seminal work in this area.

40 This is not a function of the lower number of terms of high school completed by the average black respondent in the high school group.

41 Lane, p. 142.

42 Aberbach and Walker, pp. 124–30.

43 The Gamma for whites is −.02. Respondents raised in the South and border states are coded 0, those raised in Michigan are coded 1, and those raised in other parts of the North are coded 2. Respondents who lived in more than one place are coded in the category representing the place lived in the longest between ages 6 and 18.

44 The Gamma for whites is −.09. Church members are coded 0, nonmembers 1.

45 Marxist notions about the dynamics of class consciousness make one especially interested in a longitudinal examination of the relationship between objective social status and power consciousness which covered periods of social and economic stress as well as equanimity. The expectation would be that significant numbers of lower class individuals would begin to blame the system for their powerlessness only in a time of crisis. See Lipset, p. 299.

46 See Seeman, , “On the Meaning of Alienation,” pp. 783–91Google Scholar, and “Alienation and Engagement,” pp. 472–74.

47 Incidentally, the measure of power consciousness is related to political trust with the measures of “Ability to Influence Government” and “Amount of Political Power Held by People like You” controlled.

48 For example, it is easy to imagine people who distrust the government, but feel they have a satisfactory amount of influence. Litt describes this for efficacy operationally defined in a cognitive manner, but the logic is the same. See Litt, Edgar, “Political Cynicism and Political Futility,” Journal of Politics, 23 (05 1963), 312–23CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

49 Gurin et al., pp. 31–34, 47–52.

50 Portes, pp. 232–44.

51 The study also contained a measure of participation in violent activities, but the number of participants in such activities in the type of community study from which these data were drawn was too small to permit a meaningful analysis. (Three percent of the black respondents questioned and none of the whites reported taking part in a violent protest such as a iiot or rebellion.)

I use the terms conventional and unconventional here as defined in Race in the City, p. 203: “The term conventional techniques means those customarily used in standard American electoral or pressure politics. The term unconventional techniques refers to actions, ranging from peaceful protest to rebellion, which implicitly or explicitly threaten to disrupt the normal political process. Unconventional techniques need not be illegal, although they often are.”

52 See Aberbach and Walker, Ch. 4.

53 Since both black power approval and the reasons given for power dissatisfaction are related to education, the relationship between power consciousness and black power approval was examined with education controlled. The number of cases, unfortunately, makes some of the cell sizes much too small for reliable analysis, but the pattern is quite consistent on the crucial point: those who blame the political system for failure to secure an adequate amount of power are more favorable to black power than those who blame themselves.

54 The conventional activities were voting, wearing a campaign button or going to a political meeting, contributing money to a poütical campaign, and working actively in a political campaign. The measure of unconventional activities was a composite indicator of participation in nonviolent protests such as boycotts, marches, sit-ins, or picketing. (Only ten percent of the total black sample and six percent of the total white sample reported engaging in any such activities.) See fn. 51 for reasons that reports of violent activities were not analyzed.

55 A full display of these data in detailed, tabular form can be found in Aberbach, Joel D., “Power and Consciousness: A Comparative Analysis,” paper prepared for the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, New Orleans, La., 09 4–8, 1973, pp. 25–26 Google Scholar.

56 Portes, p. 242, describes the expected data display predicted by the interaction model as one where the attitudinal or behavioral dependent variable “will be inhibited among those who, being frustrated, do not blame society for their failures and will be stimulated among those who are frustrated and blame the social order for their situation.”

57 The assumption that power consciousness causes behavior is made here in order to simplify the description. It is likely that behavior also influences power consciousness. Incidentally, controls for education (on the relationship between power consciousness and behavior) yield a rather complex pattern which is difficult to interpret with any confidence because of the small Ns in many of the categories.

58 As indicated above, too few respondents reported taking part in riots or rebellions to use this as a variable in the analysis. As a surrogate, I employed a measure of approval of such methods for showing dissatisfaction or disagreement with government policy (approved by ten percent of the total black sample and two percent of the total white sample), but approval, of course, is not the same as behavior. See Aberbach and Walker, pp. 203–06.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.