INTRODUCTION

Political violence leaves important groups of individuals at a long-term disadvantage (Mallett and Slater Reference Mallett and Slater2012). Victims of armed conflict have greater difficulty in generating income, accessing social services, and thus, are more likely to fall into poverty traps once the conflict ends (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliott, Hegre, Hoeffler, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003). This vulnerability is particularly extreme for those who are forced to flee their homes and livelihoods in search of physical security elsewhere; internal displacement exacerbates especially vulnerable conditions such as inadequate housing, unemployment, poor education, and healthcare in the reception sites (Ibáñez and Moya Reference Ibáñez and Moya2010; Moya Reference Moya2018).

Scholars have investigated the legacy of political violence on victims’ social, economic, and political attitudes (e.g., Blattman Reference Blattman2009; Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt Reference Cassar, Grosjean and Whitt2013). Some researchers have documented that conflict victims are more interested in politics, have greater political knowledge, and participate in political affairs (Blattman Reference Blattman2009; Bellows and Miguel Reference Bellows and Miguel2006; Reference Bellows and Miguel2009).Footnote 1 We posit that for a successful engagement of conflict victims in postwar political institutions, not only is it important that victims are willing to participate in political processes (i.e., the demand side) but also that elected officials are responsive to their needs and demands (i.e., the supply side). However, there is little evidence on how politicians respond to victims once the violence ends. Do conflict victims have equal access to institutions and social services? Are politicians less likely to be responsive to internally displaced individuals? Does the identity of the victim’s perpetrator influence whether politicians facilitate access to social services? Do the ideological leanings of the party in power affect responsiveness toward victims?

This article explores how politicians respond to conflict victims in post-war Colombia. Similar in design to Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope (Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012), McClendon (Reference McClendon2016), White, Nathan, and Faller (Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015), and especially Gaikwad and Nellis (Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2021) and Bussell (Reference Bussell2019), we employed a large-scale, nationwide, email-based field experiment on local authorities in Colombia to explore whether conflict victims face higher costs than ordinary citizens to access basic public services such as housing and employment programs. We tested whether local officials differ in their likelihood to respond to requests for help, their response affect, and helpfulness when requests come from conflict victims compared to ordinary citizens. Further, we evaluated how the ideological leanings of local officials influences their responsiveness depending on the ideological identity of the perpetrators.

We randomly assigned local authorities in Colombia to receive an email request for information on housing or employment in their municipalities from fictitious constituents with either explicit information of their victim or displacement status or no such information. Among those who received emails from putative victims or displaced people, we randomly varied the identity of the perpetrator, i.e., whether the political violence came from left-oriented or right-oriented actors. Analyzing replies to all 1,098 emails sent, we found clear, causally identified evidence of bias in favor of conflict victims and conflict-induced displaced citizens. Emails from victims and displaced citizens were roughly five to seven percentage points more likely to receive a reply compared to similar requests for help accessing basic social services from non-victims. Replies that victims and displaced individuals did receive were likely to be friendlier and more helpful than those received from other citizens.

We also found that local authorities did not respond to all victims in the same way. Our results revealed that left-leaning elected officials were more likely to respond to victims of left-wing armed groups in contrast to victims of the state or paramilitary groups. At the same time, right-leaning elected officials were more likely to respond to state or paramilitary victims, as opposed to victims of left-wing violence. We argue and show through qualitative evidence that this unequal responsiveness may plausibly occur because elected officials perceive that victims of violent groups on their own ideological side might particularly distrust them. As a result, elected officials respond more strongly to victims of perpetrators on their ideological side to credibly convey to these citizens their commitment to peace and their detachment from violent groups.

Our study makes three contributions to the literature on political violence and representation. First, we add to existing studies on the legacies of wartime violence. Even though the literature on the consequences of political violence has mostly focused on how exposure to war shapes civic and political engagement, scholars have neglected to investigate how politicians acting in an institutional capacity may respond to victims differently. Whereas we found positive bias toward victims and conflict-induced displaced people, discrimination against victims depends on both the identity of the perpetrator and the ideology of the elected official. Second, we point out a signaling mechanism to explain why politicians respond differently to some victims of violence over others. Third, we contribute to the study of political representation. Prior work had shown institutional systematic discrimination against minorities such as Black people, Latinos, and internal migrants, using similarly designed correspondence studies. We add to the audit experimental scholarship by applying them to study a novel and important issue–how politicians respond to petitions from victims of conflict and how the ideological history of victimization conditions that response.

DOES CONFLICT VICTIMIZATION AFFECT POLITICIANS’ RESPONSIVENESS?

Elected officials are often assumed to neutrally respond to their constituencies to maximize their chances of reelection or the overall vote share of their party (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1984). In as much as politicians seek to make good policy or help people for this purpose, providing citizens with information required to benefit from public policies may help politicians to attain their goal. Responsiveness to their citizens, and especially to the most vulnerable citizens, can help politicians to develop a reputation on social issues. In conflict-affected countries, this may include the protection of conflict victims and conflict-induced displaced citizens - which may help improve politicians’ stature among their constituents in appearing effective and competent. Additionally, the national-level implementation of transitional justice mechanisms may cause both politicians and civil servants to internalize the message that their role in assisting and redressing victims of the armed conflict is crucial for long-term reconciliation in the country.

There are reasons, however, to be suspicious about this thesis. As conflict victims are the ones most requiring protection and comprehensive social policies, their vulnerability in social and economic aspects could result in limited access to representation in the political realm (Bartels Reference Bartels2018). In most democracies, elected officials are biased toward wealthy citizens because they are more likely to have the financial and political resources that politicians need to advance their careers (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Hayes Reference Hayes2013). Furthermore, prior work sheds light on the role of taste-based discrimination. Using a similar experimental designs to ours, scholars have consistently shown that politicians racially discriminate against minority constituents such as Black people (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012) and Latinos (White, Nathan, and Faller Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015) in the U.S. context, minority ethnic groups in China (Distelhorst and Hou Reference Distelhorst and Hou2014) and Sweden (Adman and Jansson Reference Adman and Jansson2017), individuals of a different race or ethnicity in South Africa (McClendon Reference McClendon2016) and Denmark (Dinesen, Dahl, and Schiøler Reference Dinesen, Dahl and Schiøler2021), internal migrants in India (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2021), potential voters and political supporters in India (Bussell Reference Bussell2019) and, more generally, underrepresented subgroups in Brazil (Driscoll et al. Reference Driscoll, Cepaluni and Spada2018).

As underrepresented citizens, we could anticipate politicians discriminating against conflict victims. Following this same logic, discrimination would strengthen if conflict victims were also internally displaced as politicians might favor citizens who have been permanent residents in their localities (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2021). By this reasoning, we would expect negative discrimination against victims, concluding local authorities are less likely to be responsive to citizens who have been victims of the civil conflict and to citizens who suffered conflict-induced displacement compared to ordinary citizens.

Nevertheless, we might find conflict victims are distinct from other underrepresented minorities. States bear responsibility for the peace of their communities and have an obligation to protect their citizens’ right to life. These obligations extend to the postwar period as governments feel responsible for preventing, responding to, and compensating for violations of the right to life by both state and non-state actors, especially in critical moments in terms of violence cessation. Furthermore, conflict brutality erodes trust in institutions (Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt Reference Cassar, Grosjean and Whitt2013; De Juan and Pierskalla Reference De Juan and Pierskalla2016), creating a psychological barrier between institutions and conflict victims. To overcome these barriers, politicians might decide to allocate additional efforts in responding to conflict victims. As a result, we would expect positive bias in favor of victims as politicians would be more likely to be responsive to citizens who have been victims of the civil conflict.

ARE POLITICIANS EQUALLY RESPONSIVE TO ALL VICTIMS?

In postwar societies, political actors may not view all victims as belonging to the same collectivity, or at least may not treat all victims equally (Dixon, Moffett, and Rudling Reference Dixon, Moffett and Rudling2019). We argue that considering the ideological stance of the elected official who governs an institution as well as the perpetrators of violence is crucial for understanding how institutions respond to victims in facilitating their access to social services. Political responsiveness to the victimization experience may not be homogeneous but rather depends on two crucial factors: (a) the ideological leaning of the mayor and, (b) the ideological identity of the perpetrator of violence. The interaction of these two factors leads to two competing theoretical arguments.

Elected officials may see victims of their ideological rivals as deserving of restoration and reparation, whereas victims of perpetrators on their own ideological side are less so. Several reasons could explain this pattern. First, politicians could think that victims of the opposite ideological side are more likely to share an ideological affinity with them. This could be either the result of the victimization process itself – e.g., victims of rightwing violence become more leftist – or the belief that those victims are more likely to share their ideology prior due to the non-random selection of victims – e.g., victims of rightwing violence could plausibly be more leftist because rightwing violence is likely to target leftist citizens. As earlier experimental work similar to ours has systematically shown that partisan and ideological affinity shapes political responsiveness (e.g., Butler Reference Butler2014; Bussell Reference Bussell2019), we would expect that patterns of responsiveness would follow that same ideological group bias.

At the same time, in a postwar setting, politicians could believe that victims of the opposite ideological side were victims of illegitimate violence, whilst somehow more legitimate, excusable, or understandable violence came from their own side. As a form of implicitly absolving actors – with whom they share an ideological affinity – of past atrocities, officials may have lower regard toward victims of violence perpetrated by those on their own ideological side. Consequently, elected officials might neglect or minimize the victimization process of those who have suffered the consequences of violence that derived from armed groups linked to their own political ideology, leading to less commitment to responding and helping them in the aftermath of the conflict.

As a result of the above processes, the ideological group hypothesis would first suggest that institutions governed by right-wing elected officials would be more likely to be responsive to conflict victims from left-leaning armed groups compared to victims from right-wing violence (i.e., paramilitary groups and state-sponsored violent action). And, by the same token, institutions governed by left-wing elected officials are more likely to be responsive to conflict victims from right-wing violence (i.e., paramilitary groups and state-sponsored violent action) compared to victims from left-leaning armed groups.

Alternatively, politicians may be incentivized to signal their commitment to peaceful politics and disgust for violence, especially toward those who have been victims of violence by armed groups of their own ideological side. Victimization experiences may generate distrust and resentment toward those politicians who share the ideology of the perpetrators. It is not uncommon in civil conflicts that politicians ally with armed groups to achieve or hold power, making politicians incapable or uninterested in stopping the violence (De Luca and Verpoorten Reference De Luca and Verpoorten2015). Victims’ perception that institutions could not or were not willing to protect them from conflict might give rise to resentment and distrust toward the political institutions governed by politicians and parties ideologically associated with the violence.Footnote 2 To the extent that victims’ conditional mistrust is perceived by politicians, elected officials may choose to respond unequally to victims depending on the identity of their perpetrators.

Following this logic, not only should politicians have incentives to help their fellow citizens with requests, but they should also have incentives to signal to victims their rejection of violence and their commitment to peace. One way to ensure that citizens disassociate them from violent groups is to allocate additional resources to those citizens who have been victims of armed groups on the politicians’ same ideological side. In Colombia, this theoretical proposition gives rise to the following two empirical hypotheses: (a) left-wing elected officials are more likely to be responsive to victims of left-wing guerrilla groups compared to victims of right-wing violence (i.e., the paramilitary or the state); and, (b) right-wing elected officials are more likely to be responsive to victims of right-wing violence (i.e., the paramilitary or the state) compared to victims of left-wing guerrilla groups. Footnote 3

We pre-defined our research design in a pre-analysis plan (see the online Appendix R). We have not deviated from the plan on key elements of the research design (i.e., model specifications, sampling, treatment collapsing, control variables). However, the signaling mechanism was inductively theorized after the experimental results as it was not initially included as a theoretical proposition (see the online Appendix Q).

RESEARCH SETTING: THE COLOMBIAN POST-CONFLICT CONTEXT

The Colombian Conflict

The Colombian conflict has been going on for more than sixty years. Guerillas in Colombia started their insurgency in the 1960s and have their roots in the war-like confrontation period of La Violencia between members of the Partido Liberal and members of the Partido Conservador (1948-1958). Throughout the following years, several left-wing guerrilla groups were formed to continue the violent struggle to overthrow the state. The main guerrilla groups included the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and the 19 of April Movement (M-19). These groups were mainly rural and focused their attacks on fixed government positions and public infrastructure. In the beginning, they were marginal and only rarely came to the center stage of the country’s public life. In the eighties, the violence scaled up.

In parallel, the Public Forces — National Army and National Police — also played a leading role in developing the Colombian armed conflict. They were responsible for numerous human rights violations and thousands of victims, many of them in cooperation with the paramilitary groups. According to the Comisión de la Verdad (2022), the State was responsible for 56,094 homicide victims between 1985 and 2018 and 8,208 victims of extrajudicial executions between 1978 and 2016 (141).

A major right-wing armed actor emerged during the eighties: the paramilitary groups. The term paramilitarism refers to a heterogeneous set of armed structures or actors that have distinguished themselves by the use of counter-insurgent violence and vigilante justice. As political negotiations to achieve peace with the armed groups began, members of the army, right-wing political figures, and drug-traffickers created opposition guerrilla groups as a tool to defend private property (Velásquez Reference Velásquez2002). The ambition of key leaders like Carlos Castaño to coordinate training, offensives, etc. to more effectively fight the FARC led to the establishment of a nationwide paramilitary organization, las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), in 1997. Most AUC leaders demobilized between 2002 and 2006, yet other paramilitary groups remained active thereafter.

Paramilitary groups have been closely linked to the state in many ways. They were so complementary to the army’s battle strategy that they became known as the “Sixth Division” – in reference to the five divisions of Colombia’s army. Paramilitary and army soldiers coordinated on the battlefield, sharing information through intelligence, weapons, money, and objectives. While Colombian presidents might denounce paramilitary violence in public, and their leading figures could be arrested in the public eye, Human Rights Watch (2001, 1) asserted that “compelling evidence has been documented that certain Colombian army brigades and police departments continue to promote, work with, support, profit from, and tolerate paramilitary groups, treating them as a force allied to and compatible with their own.” Hence, the military and the paramilitary have together perpetrated what many consider “violence of the right,” or violencia de derecha, against left-wing guerrilla armed groups (Espinal Reference Espinal2021; Jaramillo Reference Jaramillo2008).

Throughout the sixty-year conflict, several peace talks and transitional justice processes had taken place. Before the 2000’s, political negotiations allowed for the demobilization of smaller guerrilla groups, although talks with the largest guerrilla groups were unsuccessful (Bouvier Reference Bouvier2009). After numerous military losses by the FARC, renewed peace talks between the Colombian then-president, Juan Manuel Santos, and the FARC started in 2012. Four years of a heated public discussion ensued in which citizens debated whether they should grant concessions to the FARC to reach a peace agreement. Those peace accords were defeated in a popular referendum in 2016. That same year, the President and the FARC settled on an agreement that was ultimately passed through Congress. The peace agreement ended the conflict between the FARC and the Colombian state, one of the bloodiest and longest civil conflicts in the world.

The aftermath of the conflict left a complicated picture with large groups of victims and displaced individuals. According to the final report of the Colombian Truth Commission, 450,664 people were killed between 1985 and 2018, and 7.7 million were displaced between 1985 and 2019 (Comisión de la Verdad 2022, 140). By 2022, 8,273,562 victims had been registered in the National Registry of Victims (Registro Unico de Victimas). Civilian victims represent 90% of all victims. Figure 1 shows the number of victims by the ideology of the perpetrator:Footnote 4 from left-wing groups (FARC and other guerrilla groups) and from right-wing groups (the state and the paramilitaries). Violence from the left – FARC and other guerrillas – typically used selective killings (about 30,000 victims), kidnappings (about 26,000), and enforced disappearances (about 11,000). Violence from the right was divided between the state and the paramilitaries. Most of their victims come from selective killings (about 95,000), attacks (40,000), enforced disappearances (about 32,000), and massacres (over 15,000).

Figure 1. Type of Violence by Perpetrator during the Colombian Conflict (1958-2016)

Source: Data from CNMH.

Contemporary View of Violence by Political Parties

Contemporary political parties in Colombia explicitly reject the existence of guerrillas, paramilitaries, and more generally, the use of violence to achieve political goals. However, left- and right-leaning parties have had a significant connection with political violence throughout the history of the conflict that still affects contemporary Colombian politics.

After several peace negotiations, ex-guerrilla members have been involved in politics, and many party members from the left and center-left parties are guerrilla ex-combatants. For instance, Gustavo Petro, the leader of the Partido Colombia Humana and Colombia’s new president-elect in 2022, and Antonio Navarro Wolf, member of the Partido Alianza Verde, were M-19 guerrilla members. This is also the case with the FARC political party (Comunes), which formed after the peace agreements with this guerrilla group, although this party did not win any mayoral elections. As all left parties have been trying for years to distinguish themselves from the guerrillas, some suggest that Colombia’s left is weak because the guerrillas reduce their political space (Fergusson Reference Fergusson2012).

Similarly, several politicians across the right-wing political parties have had alliances with paramilitary groups. Judicial and journalistic investigations have exposed the different pacts between national and local politicians with paramilitary groups that reflect the high degree of insertion that paramilitarism has achieved in different regions of the country (Lopez and Romero Reference Lopez and Romero2007). At least 256 politicians have been investigated by the Supreme Court of Justice and 534 investigations have been conducted by the Attorney General’s Office since 1991 for alliances of politicians with paramilitary groups. According to the Misión de Observación Electoral (MOE) of the 199 congressmen accused of these illegal alliances with paramilitary groups, 77% belonged to right-wing parties.

However, nowadays the main political leaders from these parties reject any association with paramilitary groups. Some of these politicians consider the formation of paramilitary groups and the violence generated by these groups as a historical mistake. Still today, our qualitative data from interviews with public officials and victims of these conflicts show a general perception that victims of the paramilitary groups tend to be suspicious and distrustful toward right-wing parties because of their historical ties with paramilitarism. Interviewed politicians tend to agree that victims of paramilitary groups and left-wing guerrillas still harbor hard feelings toward political parties with ties to paramilitary and guerrilla groups respectively.

Municipalities’ Competences

The Alcaldías are responsible for regulating land use in the municipal area and applying national policies to the local context. Through our own interviews with civil servants, we learned that municipalities are deeply involved in housing policy. Some of the municipalities’ faculties allow them to grant permission to develop housing plans, establish requirements for developing such plans, modify housing programs, and regulate deed permissions. Indeed, a major role of municipalities is to promote subsidy grant programs under national targeting criteria by sending a report with the inventory of properties owned by the municipality to the Ministry of Housing. The municipalities directly grant some subsidies conditional on households’ socioeconomic conditions. People displaced by violence and conflict victims have some special mechanisms for accessing housing subsidies and priority is given to them in some of the subsidies programs. These programs are often available for the entire population, vulnerable citizens and the general population, although priority is often given to the former. Importantly, when victims enjoy special benefits, these are not conditional on the perpetrator of violence.

Additionally, many of these local programs are implemented by municipal bureaucrats, which allows them to hire personnel. Municipalities can employ full-time civil service staff, as well as hire via contracting. Contracts are generally for short-term periods while civil service employees have longer tenure. The budget for civil servants is limited and conditional on revenue and population. In contrast to permanent staff, the process for contracting is more lax and flexible.

Overall, we concluded that housing and employment are two social services crucial for the vulnerable populations we studied. Furthermore, local authorities play an important role in offering information to their citizens regarding eligibility and requirements for the assignment of these programs.

THE EXPERIMENT

To test our hypotheses, we contacted every local authority in the 32 departamentos in Colombia, in total, 1,098 Alcaldías. Table 1 shows the distribution of municipalities in our sample by departamento. Footnote 5 We sent emails to publicly available addresses through which these local authorities already receive constituent requests, concerns, and complaints. The vast majority of local authorities have their own websites with an available email to receive correspondence. Our interviews with public officials and civil servants also revealed that email has become common and, in many areas of the territory, the dominant form of communication between citizens and local authorities, especially after face-to-face interactions were discouraged during the COVID-19 crisis. All public servants and elected officials that we interviewed expressed that the flow of electronic correspondence from citizens to the Alcaldías is significant, ranging from 20 to 200 daily messages depending on the municipalities’ population size. Further, nearly all elected officials, including mayors themselves, claimed that they devoted a few hours every day to personally respond to citizens’ requests via email.Footnote 6 We then concluded that using emails to request information about social services was suitable in this context.

Table 1. Number of Email Addresses Used by Departamento

Each local authority received an email with a randomly assigned text and name. Each email appeared to the local authority to be from a constituent living in her or his district making a request for information about the provision of local social services, either access to public housing or local employment. Beyond varying the type of request, we also varied the senders of the emails across the following crucial dimensions:

-

• Conflict victim. We varied whether the sender signals that he or she had been directly exposed to the conflict. Among conflict victims, we varied two further attributes:

-

– IDP status. We varied whether the individual was a conflict-induced displaced person who temporarily resided in the municipality or the individual did not mention it.

-

– Perpetrator’s identity. We varied the agent of victimization across four relevant actors: the state, a paramilitary group, ELN guerrilla, and the FARC guerrilla.

-

Additionally, the sender changed across the following control dimensions: (A) Gender; we used two names, a popular female name (“María”) and a popular male name (“Juan”), which allowed us to adjust for gender effects in responsiveness. (B) Voter registration; we varied whether the individual mentioned that she or he is registered to vote in the municipality, which enabled us to adjust strategic considerations in responsiveness. (C) Request type; we varied whether the individual requested information about the provision of local social services, either access to public housing or local employment, which ensured that our results were not due to some idiosyncratic characteristic of the request type.

To conduct the experiment, we registered domain names and created email addresses of the form [email protected] in order to send emails in a short period of time, with rolling email submissions. The field experiment was conducted on December 3/4, 2020. The text of the email is the following:Footnote 7

Good evening [Doctor, Doctora] (mayor’s name), I hope this email finds you well.

My name is [María, Juan][, and I have been a victim of the [FARC, ELN, paramilitaries, State]]. I have lived in (town’s name) for some time, [where I arrived as a displaced individual] [and have even registered to vote in the forthcoming local elections], but have not done well professionally and economically. That is why I am writing to you. I would like you to inform me of local programs I could sign up to find [employment/public housing].

Please consider that I am not associated with any ideology or political party, and that all I am interested in is improving my situation.

Thank you [Mr/Ms] Mayor.Footnote 8

In sum, there are 96 treatment conditions (

![]() $ 2\times 3\times 4\times 2\times 2 $

). Following our preregistered design, we analyze the names’ gender, voter registration, and the request types together, collapsing the study to 12 conditions. We improved balance and experimental efficiency prior to randomization by blocking on the mayor’s political leanings and departamento (Imai, King, and Nall Reference Imai, King and Nall2009).Footnote

9 As we intended to capture the heterogeneous effects of the treatments by the mayor’s ideological leanings, blocking for this factor also ensured balance on the key moderator. Figure 2 shows the number of municipalities in each experimental condition.

$ 2\times 3\times 4\times 2\times 2 $

). Following our preregistered design, we analyze the names’ gender, voter registration, and the request types together, collapsing the study to 12 conditions. We improved balance and experimental efficiency prior to randomization by blocking on the mayor’s political leanings and departamento (Imai, King, and Nall Reference Imai, King and Nall2009).Footnote

9 As we intended to capture the heterogeneous effects of the treatments by the mayor’s ideological leanings, blocking for this factor also ensured balance on the key moderator. Figure 2 shows the number of municipalities in each experimental condition.

Figure 2. Number of Municipalities in Each Experimental Condition

Measuring Responsiveness

Table 2 describes the outcome measures that were used in this analysis. The main outcome we measured was whether the email was answered within 70 days of its submission.Footnote 10 In this measure, we did not evaluate the content of the response in order to minimize subjectivity. Furthermore, we followed earlier work by investigating measures of the quality of response such as receiving a friendly or a helpful – also called meaningful or substantive – response (Costa Reference Costa2021). The friendliness of a response was measured as the sum of four independent indicators: name use (0-1), warm greetings (0-1), offer to follow-up (0-1), and a qualitative indicator of friendliness (0-3).Footnote 11 We measured helpful responses based on a qualitative assessment of whether the response included useful and meaningful information on a 0-4 scale.Footnote 12 Additionally, we kept information on two secondary outcomes: the response waiting time and the length of the response (the log of the number of words). While we did not pre-specify the outcome variables in our pre-registration plan, we have chosen to analyze all reasonable/available outcome variables.Footnote 13

Table 2. Outcome Measures

Additional Data

We collected additional data at the level of the municipality including data related to the conflict, socioeconomic variables, good governance indicators, and electoral measures from previous municipal elections. Furthermore, we measure the ideology of the party of the mayor with the official information from the National Civil Registry (Registraduría General del Estado Civil). The variable of ideological position included three categories: left, center, and rightFootnote 14 and was constructed based on the mayors’ political party.

These additional datasets are used for three purposes: (1) to evaluate the balance of the treatments (see randomization checks in the online Appendix G); (2) to increase the precision of our estimate by adding these as control variables in our models; and, (3) to act as an indicator of the ideological leanings of the mayor, the key variable to evaluate heterogeneous effects.

Ethical Considerations

In conducting the field experiment, we took the maximal care to comply with standards detailed in the APSA Principles and Guidance for Human Subject Research. A number of ethical considerations of our experimental design merit discussion. To begin with, the design of our email took into account ethical considerations discussed in similar field experiments (e.g., Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017). For this, we used publicly available and official email addresses, which implies that our interaction with local municipalities is in their professional – rather than personal – capacity. Note that our design did not aim to alter politicians’ behavior, but only to measure it (Nathan and White Reference Nathan, White, Druckman and Green2021).

Another concern regarding experiments involving elites is that researchers are using public officials’ time, potentially harming representation and service delivery processes by misallocating public resources to responding to fictitious emails (Whitfield Reference Whitfield2019). Even if this might not be true for most responses – individually taking a few minutes at most – the costs might be significant in the aggregate (Butler and Crabtree Reference Butler, Crabtree, Druckman and Green2021). For this purpose, we designed an email text that minimizes the time invested in responding to the request and we chose not to engage with the local authorities after the first email, even if the request for information was met with a follow-up question.Footnote 15

A key concern of these studies is that researchers do not internalize the costs produced to the public system, which could lead to over-use of such experiments that may pollute the subject pool (Fisher III and Herrick Reference Fisher, Samuel and Herrick2013; Leeper Reference Leeper2019). Following recent recommendations and practices in the implementations of field experiments with street-level bureaucrats (Desposato Reference Desposato, Iltis and MacKay2020; Nathan and White Reference Nathan, White, Druckman and Green2021), we estimate that the costs associated with our intervention were equivalent to 1,317 USD.Footnote 16 We believe that the societal benefits of better understanding politician responsiveness to conflict victims outsize surpass the monetary cost of our intervention.

Similar to most email-based studies, we had to use three forms of deception: identity, activity, and motivation deception (APSA 2020).Footnote 17 This deception is necessary to experimentally evaluate whether local authorities exhibit biases in their responses to citizens. Without the random assignment of victimization status and the identity of the victims’ perpetrator of violence, we would be unable to measure them. That said, our project maintains the anonymity of our subject pool and all our analyses reflect comparisons across groups of municipalities. All publicly available data are detached from identifying information.

In addition to our ethical attention in conducting the field experiment, we have also been vigilant to follow the obligations described the APSA Principles and Guidance for Human Subject Research, as well as in prior literature on ethics in doing fieldwork in fragile contexts (Cronin-Furman and Lake Reference Cronin-Furman and Lake2018) when conducting the interviews. We now provide an overview on the steps we took to detect and minimize risks derived from our research. We conducted 23 semi-structured interviews in 16 field sites in June/July 2021. We interviewed mayors and other elected officials, and civil servants. During the interviews, our conversation discussed (1) major policy areas being developed in the municipality (e.g, employment and housing); (2) the frequency and mechanisms of interaction between local policymakers and citizens; (3) the effects of the civil conflict in the municipality; (4) how local policymakers perceive the attitudes and institutional trust of victims and displaced individuals; (5) the motivations behind policymakers’ responsiveness to victims. We ensured the confidentiality of the interviews and collected minimal identifying information (position and municipality). All interviews were conducted in Spanish. Translation or transcription were not required as the authors are proficient in the local language.

Prior to each interview, we presented authors’ identification cards and an informative letter in a paper copy that included information about the goals of the project, the topics that would be discussed during the interview, the expected length, the COVID-19 safety protocol, the right to terminate the interview at anytime with no consequence, and contact information of the authors. After reading through the informative letter, verbal consent was obtained from the interviewees before each interview.Footnote 18

RESPONSIVENESS TO CONFLICT VICTIMS

Figure 3 presents the difference in response rates to requests for help between victims and non-victims. Figure 3A shows that the mayor offices’ response rate to requests for help increased from 30.6% in the control group, where victimization is not mentioned, to 35.7% in the experimental group where the help request came from a putative conflict victim (p = 0.09).Footnote 19 This change of 5.1 percentage points, which is equivalent to an increase of 16.6% in the response rate, is consistent when using OLS regression with control variables. In the online Appendix K, the treatment effect after adjusting for all control variables was 6.2 percentage points (p = 0.039), which is equivalent to an increase of 20.3% in responses from putative victims compared to non-victims.

Figure 3. Differential Responses to Requests of Help by Victimization Status

Note: Differences are reported in percentage points (pp) or standard deviations of the pooled sample (SD) and p-values are based on two-sided t-tests. N = 1,098.

Figures 3B and 3C report similar results when using indicators of the quality of the response received, whether it is a “friendliness” or a “helpfulness” score. Figure 3B shows that the conflict victim treatment significantly increased the local bureaucracies’ friendliness from an average of 0.77 in the non-victim condition to 1.22 in the conflict victim treatment (p < 0.001), a change that is equivalent to 0.25 standard deviations (SD) in the friendliness score of the pooled sample. Similarly, Figure 3C shows that responses to requests for help from conflict victims are also more helpful than similar requests from non-victims. More specifically, the average helpful response score to requests from non-victims is 0.47, compared to a 0.58 among victims (p = 0.07). This difference implies an increase of 0.11 SD in the outcome. In the Online Appendix K, we show that these treatment effects uphold when controlling for an extensive set of pre-treatment control variables and adding department-fixed effects, as well as using the response timing or response length as dependent variables.

We complement this analysis by examining the differential responses to requests of help from citizens who are not only victims but also individuals who are conflict-induced internally displaced people (see the online Appendix J). We find that the displacement victim treatment led to a significant increase in mayor offices’ response rate, as well as the friendliness and helpfulness of these responses. Because of the large number of IDPs conflict victims in Colombia, it is likely that, when not specified, elected officials might read the email assuming that victims are IDPs, which probably explains the similar effects found between conflict victims and IDP victims.

IDEOLOGY, PERPETRATOR, AND RESPONSIVENESS

We now turn to evaluate the role of political considerations in officials’ responsiveness to conflict victims. Figure 4 plots the differences in response rates to requests by victimization status and the ideological leanings of the mayor. Figure 4A shows that municipalities governed by mayors with a left-leaning ideology (black bars) are more likely to respond to requests from victims of left-wing armed groups (FARC or ELN), which might have presumed right-wing sympathies, than to similar victims of violence from the state or paramilitary armed groups, which might have presumed left-wing sympathies. The response rate among the municipalities with a left-leaning mayor is 43.4% when contacted by a victim of the FARC or the ELN guerrilla group compared to only 24.4% when the request is from a victim of the state or the paramilitary. This means that the increase in response rate is 19 percentage points, which is equivalent to a sizable increase of 78%, and statistically significant at the 99% confidence level. When contacted by non-victims, the response rate among municipalities with left-leaning mayors was 35%, which is lower than the responsiveness from victims of left-wing armed groups, and greater than the responsiveness from victims of right-wing violence.Footnote 20 This evidence is fully consistent with signaling-based responsiveness.

Figure 4. Differential Responses to Requests for Help by the Identity of the Violence Perpetrator and Mayor’s Ideological Leanings

Figures 4B and 4C reveal a similar pattern for the other two outcomes of interest. Municipalities whose mayor belongs to a left-of-the-center political party provided friendlier and more helpful responses to victims of left-wing guerrillas than to victims of the state or the paramilitary. In particular, messages from these had, on average, a friendly response score of 1.46 when responding to victims of left-wing armed groups compared to the average of 0.81 when responding to victims of the state or the paramilitary, or 0.86 when responding to non-victims. The difference between responding to victims of left-wing violence compared to right-wing violence is substantive in magnitude, an increment of 80% that is also equivalent to an increase of 0.34 SD in the friendliness score, which is statistically significant at the 99% confidence level. Similarly, messages from municipalities with a leftist mayor were deemed to be more helpful when they are responding to victims of left-wing guerillas – with an average helpfulness score of 0.65 – than when responding to otherwise similar victims of the state or the paramilitaries – with an average helpfulness score of 0.40 – or to non-victims – 0.49. This increase in helpful responses from victims of right-wing violent groups to left-wing guerrilla groups is statistically significant at the 99.9% confidence level and, from a substantive perspective, equivalent to an important increment of 0.26 SD in the helpfulness score.

The effects were reversed for those municipalities with a right-leaning mayor (light bars). Figure 4A shows that these municipalities were more likely to respond to victims of state violence and paramilitaries – with an average response of 39.9% – compared to victims of left-wing armed groups – with an average response of 31.9% – or non-victims – with an average response of 29.7%.Footnote 21 The difference in response rate between victims of leftist and rightist violence is 8 percentage points, which is equivalent to a decrease of 20%, although not statistically significant at standard thresholds of significance (p = 0.13). Figures 4B and 4C confirm this pattern. Those municipalities with a mayor from a right-of-the-center political party provided friendlier and more helpful responses to victims of the state and the paramilitaries – with an average friendliness score of 1.39 and a helpfulness score of 0.67 – compared to victims of the left-wing guerrillas – with an average friendliness score of 1.15 and a helpfulness score of 0.50 – and non-victims – with an average friendliness score of 0.80 and a helpfulness score of 0.50. While these differential scores are substantively important in magnitude with implied decreases of 0.15 and 0.18 SD respectively for friendliness and helpfulness, we lack power to ascertain that they are different from a null effect as these differences do not reach standard levels of statistical significance in a two-tailed t-test (p = 0.30 in the friendliness score model and p = 0.11 in the helpfulness score model).Footnote 22

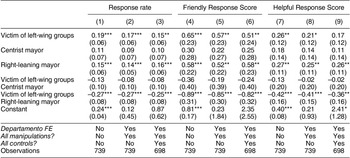

To evaluate this interactive hypothesis, we increased the precision of our estimates in two ways: (a) we estimated an interaction model where the factor of the ideological leanings of the mayor (whether left, center, or right) interacted with the identity of the perpetrator (whether a left-wing armed group (ELN or FARC) or right-wing violence (state or paramilitary groups) in a regression framework, and (b) included relevant pre-treatment covariates in our models.Footnote 23

Table 3 presents several model specifications. The treatment effect of a victim from a left-wing armed group among municipalities with a leftist mayor on the response rate was positive and statistically significant, ranging between 0.15 and 0.19 across the three specifications. The effect was also positive and statistically significant on the friendliness score, ranging from 0.51 and 0.65. Although the treatment effect remained positive on the helpfulness score, it was only statistically significant in the model without controls, ranging from 0.17 to 0.26. The treatment effects of the identity of the perpetrator on response rate, friendliness, and helpfulness were not significant for the municipalities with a centrist ideology. However, the treatment effect among municipalities with a rightist ideological leaning was negative, which means that they were much more likely to respond, and provide a friendly and a helpful response to victims of the state and the paramilitaries than victims of leftist violent groups.Footnote 24

Table 3. The Interaction Effects of Mayor’s Ideology and the Identity of the Perpetrator

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

See the online Appendix L for the full models and the models with the time to response and response length as outcome variables.

To provide further credence on the signaling-based responsiveness, we could expect the signal-based mechanism to operate most strongly on politicians who wished to signal their neutrality, but less strongly on bureaucrats carrying out a technical assignment.Footnote 25 In the online Appendix P, we show that the results remained unaltered when considering only the responses by politicians, yet they were substantially smaller and statistically less reliable when we only considered responses by non-politicians. This pattern is consistent with what we would expect from signal-based responsiveness.

Even if the distribution of requests by each type of victim was randomly assigned, one could reason that responsiveness might have been different depending on whether leftists or rightist groups were active in the municipality. The online Appendix L aims to minimize this concern by re-estimating the analysis after including an extensive set of controls. These included the level of violence in the municipality by each of the relevant perpetrators. The results show that our main findings remained largely unaltered. Further, we have also examined whether mayors’ ideological leanings were associated with the levels of observed violence of a given perpetrator in a municipality (see the online Appendix O). Table O.2 indicates that while left-leaning (right-leaning) mayors were more (less) likely to govern in conflict-affected areas, they were similarly likely to govern municipalities affected by leftist and rightist violence. Overall, there was no clear pattern regarding the identity of the perpetrator in municipalities governed by left or right mayors.

EXPLORING THE MECHANISMS

As shown in the results section, municipalities governed by mayors with a partisan leaning were more likely to respond to requests from victims of armed groups that subscribed to their same ideology in comparison to similar victims whose perpetrators fell on the opposite side of the ideological spectrum. Our theoretical framework was derived from a signaling-based hypothesis, yet our findings could also be consistent with the presence of guilt-based responsiveness.

Politicians might feel guilt for what armed groups close to their ideological stances might have done to victims in the past. According to this view, they may sense some responsibility for the harm these armed groups have caused or for the relationship their political party had with those illegal armed groups. Consequently, politicians may be more attentive and more responsive as a result of the remorse they feel for these victims more so than victims of perpetrators motivated by the opposite ideological position.

Alternatively, signaling-based responsiveness, as we define it, means that politicians do not feel any remorse or guilt because they do not identify themselves with any armed groups. Politicians, however, are aware that victims tend to distrust politicians, and political institutions at large, on the same ideological side of the victims’ perpetrators because they are aware that victims perceive that they failed to be protected by institutions. Consequently, politicians have an incentive to separate themselves from armed groups on their own ideological side to regain victims’ confidence with the authorities, leading them to pay greater attention and respond quickly and helpfully to these victims.

To examine whether guilt might have driven our findings, we drew on interviews conducted during two months of fieldwork in Colombia. The qualitative evidence discussed in this section fell outside our preregistration documents. Given the discrepancy between the preregistered hypotheses about ideology/partisanship and our finding, we believe it also represents additional information to reinforce the plausibility and meaningfulness of the signal-based responsiveness.

We interviewed mayors, elected officials, and civil servants from several Colombian municipalities across the Departamentos of Bolívar, Cundinamarca, Boyacá, Santander, and Valle del Cauca. Rather than obtaining a representative sample, our sampling focused on selecting municipalities that would reflect an array of attributes. These included small (e.g., Sáchica in Boyacá with less than 4,000 inhabitants) and large (e.g., Buenaventura in Valle del Cauca with over 400,000 inhabitants); prosperous (e.g., Guasca in Cundinamarca) and low-income (e.g., El Playón in Santander); and, conflict-affected (e.g., Simacota in Santander or Carmen de Bolívar in Bolívar) and barely-affected municipalities (e.g., Guasca, Cajicá, and Tenjo in Cundinamarca). While the interviews took place in the months of June-July, 2021, the audit experiment took place in early December 2020. Because the time lapse between the experiment and the interviews is over 6 months, it is highly unlikely that the two methods could have interacted in any way. In fact, none of the interviewees mentioned the audit experiment during the interviews.

From our interviews, we found that the signaling-based mechanism seems to be the channel that explains politicians’ additional efforts to respond to victims from armed groups on their ideological side. When we asked in our interviews whether they felt remorse for the violence, none of them showed guilt or indicated that they felt responsible for what armed groups had done to conflict victims. When arguing the importance of prioritizing victims of the conflict, we did not find any reference to a need to redress their own misbehavior. What we systematically found was an explicit attempt to separate themselves from the perpetrators of violence. In fact, all mayors and political appointees saw themselves as having no link with those who had committed violence on their own ideological side and, consequently, expressed no room for guilt or remorse in their evaluations. The following statement from an official from a right-wing government illustrates how politicians dissociate themselves from armed groups’ actions:

“Those who should be there (public officials) have to be humanitarians and unimpeachable people who have been correct. It is not right that people who have killed, murdered, raped women or children hold public office. The people who act correctly are the ones who should govern us… we must be correct and blameless. People who have belonged to armed groups do not have the morals to do so…I say this in a general way for all armed groups, and not only for the guerrilla groups.”Footnote 26 (Interviewee 1)

In all the interviews, a recurring theme was to mention the efforts they, as local politicians, had had to make to regain the victims’ trust in their institutions and to eliminate the victims’ wariness towards politicians and political parties. Our qualitative data suggests that politicians and public officials need to signal that they are committed to peace by eliminating any potential association with armed groups. The secretary of government from a conflict-affected municipality whose government was linked to illegal armed groups exemplifies this effort:

All the administrations were humiliated by the armed actors; many took one side or the other, governance did not exist. This municipality was no man’s land…The authority was in the hands of the violent groups. You can imagine the loss of confidence that existed at that time. Since then, the government has started a very strong fight to regain confidence, and the citizenry is gaining confidence with the institutions, but it is a slow process…The city council, as well as governments at all levels, is making an extraordinary effort with the victims so that they feel that the governments are theirs. We made some laws that protected many victims. Many have received benefits. This intervention they are making, at a security and social level, is consolidating trust with the government. (Interviewee 2)

Identically, an interviewed mayor from a municipality that had historically been heavily affected by rightist violence linked to the local government and police, also argued it was necessary for her to make significant efforts to regain the trust of the victims. This interview also showed that the politician’s perception of mistrust among the victims is not generalized to all institutions and parties but specific to institutions and authorities that the victims could perceive as responsible for the violence. In this particular case, this referred to the local government itself, the police, and the army. Today’s mayor emphasized the importance of signaling that she is committed to peace when interacting with the victims:

The victims have generated some suspicion of the government and, above all, of the local government… There has always been pain, a feeling that the government has forgotten them, that they are not developing because the institutions have forgotten them…That distrust of the victims with the local government forces us to make a more important effort, especially to the police and the army. We tell the police to go out, do social work, and do activities with the children and young people, who are the future, so that all of them regain confidence with the authorities and disassociate them from those events that marked this society. (Interviewee 3)

Other public officials from municipalities not affected by violence expressed the same distrust from conflict victims. They argued that displaced victims have negative experiences with authorities, which translate into distrust in the new municipalities where they arrive:

They come from those territories (territories highly affected by violence) and bring those negative experiences with the institutions there and get confused. That’s why they distrust them. They do not trust the institutions and come to this territory with a great deal of prevention. (Interviewee 4)

Hence, politicians in municipalities that host displaced individuals also feel the need to signal that they can be trusted and that they are distinct from violent groups. In this sense, a public official from one of these municipalities argued:

The victims’ mistrust of the government was created during the years of the conflict… The suspicion of the victims can be seen all the time…In that area (a municipality affected by paramilitary violence), you see the cleansings and curfews …The local governments have had links with paramilitarism…For sure, there is an effort (from the municipality receiving victims) to compensate the victims and prevent violence from recurring. The mayor works hand in hand with all the victims’ programs; there is follow-up. (Interviewee 5)

By the same token, a mayor from a municipality that hosts numerous displaced victims also reflected on the special mistrust of victims toward parties that were linked to those who perpetrated violence against them.

It is very hard for victims and their relatives to accept that some political parties accept ex-combatants among their ranks or succeeded armed groups. I imagine that there must be a lot of pain among those who saw their houses burned, their relatives’ bodies dismembered or killed in the streets. They must be very suspicious especially toward these parties. These parties must make additional efforts to overcome this resentment. (Interviewee 6)

To sum up, our qualitative data was precise in showing no evidence of any guilt-based considerations. Even when asked directly, no politician or public official expressed at any time during our interviews that they had some responsibility for the violence, and no one expressed remorse for what former members of their party have done in the past within the context of the conflict. Instead, politicians and public officials have repeatedly argued for the need to signal their separation from violent groups and be responsive to victims that distrust them without the presence of guilt.

On another matter, there could be two types of plausible signals as local officials signal a position when they respond to constituents who have been harmed by militias/rebels who align more closely with their political party: peace-committing and policy moderation signaling. On the one hand, politicians might respond to victims of violence from their ideological side to signal a commitment to peace-building as an attempt to regain the institutional trust that victims lost during the conflict; detaching themselves from violent groups. On the other hand, politicians could signal their ideological moderation by showing that they are not affiliated with the extremist elements of the left or right; detaching themselves from extreme groups on policy/ideological grounds. In the latter, signaling would be based on moderating their positioning relative to socio-economic policies, i.e., extreme socialism or conservatism, and unrelated to the conflict itself, i.e., violent groups.

The qualitative evidence sheds light on the plausibility of these mechanisms. In the interviews, we found evidence that the detachment is from violent episodes and events that involved the role of the institutions. For example, interviewee 3 explicitly mentioned that “the police and the army” should work to “regain confidence with the authorities and disassociate them from those events that marked this society.” In this case, the disassociation is not from those who pursue extreme policies on ideological grounds, but it is explicitly stated that they thrive for a disassociation from “those events that marked this society.” In particular, this case refers to a massacre conducted by a paramilitary group in the municipality about 20 years ago. By the same token, the excerpt from interviewee 5 expressed that institutions attempt “to compensate [for the institutional wrongdoings of the past] the victims and prevent violence from recurring.” Hence, they sought to disassociate themselves from the institutions that collaborated with the paramilitaries to victimize the local population. These patterns show that the local officials sought a detachment from groups extreme on the peace/violence dimension rather than along any other dimension.

Overall, a plausible concern of our interviews is the potential presence of social desirability bias. While this bias can always be an issue in interviews (as with many other methods), one can imagine that public officials would feel pressured to express remorse for violence conducted by “their” side (i.e., groups more aligned with their ideological leanings). Thus, social desirability bias could lead us to find support for either hypothesis. However, our interviews did not suggest that guilt was present, but rather signaling.Footnote 27

DISCUSSION

Political conflict leads to significant social and economic costs for entire countries and devastates the lives of victims and their families. Once violence ends, victims tend to remain impoverished for generations (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliott, Hegre, Hoeffler, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003). While intense academic debates have been devoted to the effects of war on victims’ social and political attitudes (e.g., Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016), this paper shifts the focus by evaluating how politicians as individuals acting in institutional capacity responded to conflict victims in the postwar period. We offer field experimental evidence from postwar Colombia to evaluate whether individuals’ victimization status influences politicians responsiveness, and we causally identify the influence of victimization status on the real-world behavior of elected officials.

Our first set of findings offers much in the way of optimism about how elected officials embrace victims in the aftermath of conflict. We found strong evidence that elected officials were more responsive to conflict victims and conflict-induced displaced citizens. Moreover, the responses that conflict victims received to requests for access to housing and employment were friendlier, and more likely to be informative than those received by ordinary citizens. While scholars had previously shown that institutions discriminated against underrepresented minorities across a variety of settings (e.g., Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012; McClendon Reference McClendon2016), politicians in postwar settings felt compelled to compensate for the state’s failure to protect by favoring conflict victims in facilitating their access to social services. Based on our interviews, we found that while elected officials generally asserted that they were willing to respond to all citizens equally, they also admitted that conflict victims and displaced individuals deserve special treatment vis-à-vis their interaction with the local administration.

Despite the increase in responsiveness toward conflict victims in general, our second set of findings showed that not all victims were treated equally. More specifically, we have provided causally identified evidence that institutions governed by politicians of right-wing parties were more likely to respond, be friendlier, and more helpful in their responses when email senders had been victimized by the army or the paramilitaries rather than guerilla groups. The opposite also holds. Institutions governed by politicians of left-wing parties were more likely to respond, be friendlier and more helpful in their responses when senders had been victimized by guerrilla groups rather than right-wing armed groups. We argued that politicians were more likely to be responsive to citizens who had been victimized by armed groups that were ideologically linked to them as a form of signaling to victims that they were committed to peace and detached from violence.

This evidence builds on our earlier optimism. Because politicians’ favoritism was directed toward those victims who they anticipated could foster more resentment against them, victims could update their views about elected officials and political institutions positively when they experienced that those who they may initially be suspicious of were effectively responding to their demands. In the aggregate, this imbalance may foster greater social and institutional trust among victims, which is commonly seen as a critical factor for ensuring economic and political recovery, reconciliation, and durable peace in war-torn societies.

Our findings likely yielded a lower bound for politicians’ greater responsiveness to the populations studied: conflict victims in general, and victims of groups linked to politicians’ ideological side. As earlier scholars have noted, actions that are costly and time-consuming produce greater bias than those that are simple and short (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1968; White, Nathan, and Faller Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015). Hence, interactions that require processing paperwork, requesting documentation, submitting a petition, or filing a complaint may be more complex and could result in greater favoritism toward victims. Due to the short and straightforward email-based design of our experiment, our estimate is likely to be a lower bound of unequal responsiveness.

Under what circumstances might we expect victimization status to trigger politicians’ responsiveness, as in Colombia? What contextual conditions favor the influence of ideological considerations in the response to conflict victims? In other words, can we say anything about our experiment’s scope conditions that would allow us to generalize the Colombian evidence to a broader set of postwar settings? While the following discussion is inevitably speculative, we believe that a process in contemporary Colombia, which is common to many postwar settings, may help explain our findings: the widespread belief among politicians that the state bears responsibility for the social consequences of the conflict, requiring state efforts to compensate victims.

In the last decade, the Colombian state has developed several transitional justice mechanisms, alongside several peace agreements with the paramilitaries and the guerrilla groups, to accommodate victims, reintegrate ex-combatants, and seek social reconciliation. The Law of Victims and Land Restitution approved in 2012 included several measures to assist and redress victims of the armed conflict. Among other things, this law created the Unit for Comprehensive Attention and Reparation to Victims (Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas), which helps to identify, assist, and coordinate victims with political institutions. While the development of these procedures is certainly incomplete, the countrywide policies have likely affected elected officials across public institutions, creating a general belief that victims deserve special attention compared to ordinary citizens. By all accounts, Colombian local politicians have integrated that message. As revealed in our interviews, mayors and other officials have repeatedly asserted a special commitment of service and attention toward conflict victims.Footnote 28 Such responsiveness to this collectivity is believed to be part of the reparation and healing processes of Colombian society. In the absence of politicians’ beliefs in their significant role in the reparation process, we suspect that the positive bias we found would likely have been less salient. However, the Colombian case is not an exception across postwar societies. As countries emerge from periods of conflict and large-scale repression, transitional justice mechanisms are being developed to provide accountability for perpetrators of violence and redress for victims, and politicians often internalize their role in that process.

Another relevant feature of the Colombian case is that the ideological dimension of conflict maps on to politicians’ ideological orientations. This is common in comparative terms as postwar political competition often reflects the relevant parties during the conflict, be it on ideological grounds or along ethnic groups. Hence, we believe that our results could plausibly generalize across a considerable number of countries emerging from civil conflict. Building upon these findings, we hope to spur further research on the political responsiveness to conflict victims in other contexts to examine under what conditions the patterns of responsiveness we observe could generalize to other contexts with non-democratic settings, weaker institutions, or ethnic-based group attachments.

The core empirical finding we established – that institutions are more responsive to conflict victims, and especially victims of groups on the mayor’s opposed ideological side – is reason for optimism regarding the relationship between elites and victims. Our results speak to the possibility for rapid political and social recovery after conflict across many postwar societies, the tendency of victimized individuals to become more politically engaged (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016), and the effect of war on governments’ implementation of egalitarian policies and progressive taxation (Scheve and Stasavage Reference Scheve and Stasavage2010; Reference Scheve and Stasavage2012). Our evidence also suggests that institutions may be playing a central role in ensuring victims’ reintegration by increasing their responsiveness and accommodation within the political and social system, which may be a crucial factor in fostering long-lasting peace in societies emerging from wars.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001277.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the APSR Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EORLRJ.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for feedback from Joseph Brown, Mario Chacón, Aaron Kaufman, Robert Kubinec, Abdul Noury, Giuliana Pardelli, Leonid Peisakhin, Melina Platas, and Ernesto Verdeja. We also thank Vanessa Florez for her assistance with our fieldwork.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The research was supported by grants from New York University Abu Dhabi.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research. The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the New York University Abu Dhabi Review Committee and certificate numbers are provided in the appendix.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.