Introduction

Does money matter in the uphill battle for gender-balanced representation in politics? Men and the rich are overrepresented in national parliaments across the globe and progress toward gender balance has been arduous, uneven, and slow (Carnes Reference Carnes2018; Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2016; Celis and Lovenduski Reference Celis and Lovenduski2018; Giger, Rosset, and Bernauer Reference Bernauer, Giger and Rosset2012; Hughes, Krook, and Paxton Reference Hughes, Krook and Paxton2015; Krook Reference Krook2009; Murray Reference Murray2014). Given that gender balance in representation is crucial for enhancing quality in democracy just as much as economic equality, stable democracies may be far less democratic than they seem, suffering from a gender democratic deficit. As Dahlerup (Reference Dahlerup2018) asks, “Have democracies failed women?”

Research thus far has not paid sufficient attention to the financial dimension in overcoming gender deficits. On the one hand, studies on political financing and democratic quality have raised unequal access to financial support as a core concern, if not a major impediment, for vigorous electoral competition with little mention of gender-based inequality (e.g., Beetham Reference Beetham2000; Diamond and Morlino Reference Diamond and Morlino2004; Pinto-Duschinsky Reference Pinto-Duschinsky2002; Van Biezen and Kopecký Reference Van Biezen and Kopecky2007). On the other, comparative studies on gender and representation have only partially factored in gendered patterns of wealth inequality, with some notable exceptions (Bauer Reference Bauer2010; Bernauer, Giger, and Rosset Reference Bernauer, Giger and Rosset2015; Bernhard, Shames, and Telee Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Hinojosa Reference Hinojosa2012; Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Matland Reference Matland1998; Muriaas, Wang, and Murray Reference Muriaas, Wang, Murray, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020; Murray, Muriaas, and Wang Reference Murray, Muriaas and WangForthcoming; Sanbonmatsu and Rogers Reference Sanbonmatsu and Rogers2020).Footnote 1

The goal of this article is to better integrate these two disconnected bodies of work to advance understanding and theory about the importance of money and economic inequality in the struggle for gender-balanced democracy through the systematic analysis of a relatively new policy tool: “gendered electoral financing,” or GEF (Muriaas, Wang, and Murray Reference Muriaas, Wang, Murray, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). Designed to level the playing field by redirecting streams of funding to purposefully promote women in elections through payments to women candidates and political parties or penalties to parties, GEF has the potential to reduce the gender democratic deficit. This study takes to heart the lessons learned from the rich comparative research on gender quotas worldwide—that they are not a stand-alone magic bullet and that there is a need to “go beyond quotas” (Krook and Norris Reference Krook and Norris2014)—to consider other strategies, initiatives, and policies in combination with quotas that increase women’s representation. With this in mind, the research question examined here is whether, how, and why gendered electoral financing, in combination with other crucial factors like quotas, changes the behavior of party gatekeepers so that gender balance in national legislatures is enhanced.

GEF initiatives, at “the crossroads of gender representation and political party finance regulation” (Feo and Piccio Reference Feo and Piccio2020a, 904), have received minimal attention, mostly through single-country studies that lack uniform measurements. This article focuses on national legislative elections in democracies as a first step. Hypotheses are tested from previous research in a mixed methods study of GEF implementation in 31 legislative elections in 17 countries.Footnote 2 The study design brings together qualitative comparative analysis that allows for the potential of GEF implementation to combine with other conditions to produce successful outcomes and two causal mechanism cases studies of GEF implementation over the long haul in France and Malawi.

Gendered electoral financing is mapped out in terms of two approaches: top-down instruments that are designed and implemented by state actors and bottom-up initiatives that are pursued through societal actors. The integrated mixed methods findings confirm that both top-down and bottom-up measures can improve gender balance in legislatures significantly when combined with certain conditions by providing the needed financial incentive to change gatekeeper behavior. While the recipe for the success of top-down mechanisms is predicted and simple—in half of the cases for success and one third of all cases of GEF implementation—state-driven instruments combine with quotas and either proportional representation electoral systems or a 15% minimum of women MPs; in bottom-up implementation the recipe is unexpected and complex and does not include quotas. Surprisingly, the analysis shows that whether a GEF instrument is a carrot (payment) or a stick (penalty) is not a crucial ingredient for success.

In the rest of the article, the micro foundations, mechanisms, and dynamics of the two approaches are first presented and then the working hypotheses for the different potential pathways to successful implementation outlined. The mixed methods design is discussed and then the analysis turns to the QCA findings. The two minimalist causal mechanism country case studies, covered in the following section, hone in on the drivers that transform failures into successes over the long term, bringing in important factors omitted in the QCA. The article ends by integrating the findings of the mixed methods analysis and discussing theoretical and policy implications with respect to the struggle for gender-balanced representation and reducing the gender democratic deficit across the globe.

Current Knowledge and Theory about GEF: The Potential Paths to Success

Mapping GEF: Top-Down (TD) vs. Bottom-Up (BU) Approaches

Whereas political financing takes many forms, it is generally defined as “money for electioneering” (Pinto-Duschinsky Reference Pinto-Duschinsky2002, 70). Diamond and Morlino (Reference Diamond and Morlino2004, 29) argue that democratic quality requires the prevention of “subtle denigrations of electoral rights” and an awareness about how “equality in access to political finance” is often denied. Beetham further elaborates this position by posing the question: what is the value of the political right to stand for elected office if it is only accessible to the wealthy? He suggests that even if “civil and political equality does not require complete economic levelling” (Reference Beetham2000, 97), some sort of action is needed to address the political scope of wealth. For Beetham, the electoral playing field can be tilted by either adding “legal restrictions” on electoral financing to limit the wealthy or by better equipping those with meagre means through “positive attention.” Whereas Beetham pays less attention to what it takes for positive attention to bear fruit, he does indicate a pathway that is more complex, general, and situated in society compared with the state-based approach that is more regulatory.

While these discussions of the relationship between economic inequalities and democratic quality in the 2000s ignored gender issues, Mansbridge had already acknowledged a gendered effect in Reference Mansbridge1999. She argued that the uneven access to funding for marginalized groups, like women, over the long term had left these groups with fewer resources for organizations to make their voices heard. GEF initiatives are based on similar assumptions about electoral financing; there is a need for funding schemes that either motivate more women to stand for election or that convince parties there are no, or at least minor, financial drawbacks connected to backing women candidates, and potentially financial rewards. Given that to win elections parties must use ever-increasing expensive campaign techniques (Childs Reference Childs2013), party leaders are obliged to carefully consider the costs of selecting certain candidates over others, making GEF a potentially powerful tool to incentivize the selection of women candidates.

The logic of Beetham’s two categories helps to map GEF initiatives. “Legal restrictions” are government-led top-down approaches that penalize or pay parties through public funding to make parties comply with a given gender-balance goal. They are initiated and implemented by the government, often involving women’s policy agencies, and in many cases operate in conjunction with legislated quotas, like in France (Achin et al. Reference Achin, Lévêque, Durovic, Lépinard, Mazur, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020; Mazur et al. Reference Mazur, Lépinard, Durovic, Achin and Lévêque2020). The “positive attention” strategy is bottom-up, as Beetham implies. It includes GEF instruments introduced by nongovernmental actors that cover electoral costs for women that make women candidates more financially appealing for parties to back. Examples include, EMILY’s List in the US (Kreitzer and Osborn Reference Kreitzer and Osborn2019) and the WIN WIN! initiative in Japan (Gaunder Reference Gaunder2011). While the arena is clearly different for each approach, state-based versus society-based, whether a penalty or payment is used does not necessarily match a particular approach. Top-down instruments can either provide a penalty or a payment for parties to comply, but bottom-up mechanism always involve “carrots” rather than “sticks”—giving a boost to women who run for office.Footnote 3 A top-down approach is not limited to legislation alone; funding initiatives that are facilitated and organized by the state bureaucracy may be included. The strategy adopted largely depends on the political financing regime at work in a particular context (Van Biezen and Kopecký Reference Van Biezen and Kopecky2007).

Variation across Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches: The Limits of Case Study Research

Country case studies reveal that success—a significant increase in gender balance in parliament—has been mixed regardless of approach and suggest some important lessons about the dynamics and determinants of the two different modes. Piscopo (Reference Piscopo2016), for example, shows in Mexico that top-down strategies, punishment as well as payment, are more likely to succeed. Ohman (Reference Ohman2018) concludes, in a study of top-down GEF, that simply introducing a connection between gender and public funding is unlikely to produce a change by itself and that these regulations are in danger of becoming purely symbolic. Alternatively, Piscopo (Reference Piscopo2015) argues that funding mechanisms are neither irrelevant nor symbolic, as they constitute highly significant interventions into what happens behind closed doors within political parties. Studying the top-down policies that have been implemented in Italy, Feo and Piccio (Reference Feo and Piccio2020a; Reference Feo and Piccio2020b) find that success is also limited; positive effects are only maximized when different policy instruments complement each other and share the same policy goals. In Cabo Verde, top-down measures were adopted in legislation but never implemented (Borges, Muriaas, and Wang Reference Achin, Lévêque, Durovic, Lépinard, Mazur, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). In Chile, the GEF scheme was insufficient to level the electoral playing field because of the disadvantage women have as electoral newcomers (Piscopo et al. Reference Piscopo, Hinojosa, Thomas and Siavelis2021).

With respect to bottom-up approaches, Kayuni and Muriaas (Reference Kayuni and Muriaas2014) find in Malawi that campaigns directly targeting women can contribute to an increase in gender-balance if the context is conducive for change. Gaunder (Reference Gaunder2011) studying Japan and Bauer and Darkwah analyzing Ghana (Reference Bauer, Darkwah, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020) paint a bleaker picture. In Ghana, a reduced filing fee for women aspirants is not enough for women to make it to parliament. While women’s recruitment groups in the US, a potentially bottom-up avenue, have been studied by Kreitzer and Osborn (Reference Kreitzer and Osborn2019), these groups focus on the recruitment and training of women candidates but not funding and, thus, are not considered as GEF in action.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis as the Best Path to Construct a Theory of GEF

The country case research provides interesting insights; however, the absence of uniform measurements undermines the validity of individual case studies and the reliability of cross-case comparison. Nonetheless, this body of work shows that progress can be made through both types of GEF through a shifting interplay between certain conditions. Qualitative comparative analysis, therefore, based on premises of configurational causality—outcomes are a product of a combination of conditions—and of equifinality—multiple combinations of conditions or paths to the same outcome—is a useful analytical tool to understand the interplay of GEF with other conditions.Footnote 4 Scholars in gender and politics often opt for QCA over statistical analysis in larger-n studies due to the highly complex nature of gendered dynamics at play (e.g., Ciccia Reference Ciccia2016; McBride and Mazur Reference McBride and Mazur2010). Krook (Reference Krook2010) and Lilliefeldt (Reference Lilliefeldt2012) specifically assert in their studies of gender and representation that QCA is a more appropriate methodological approach than correlational analysis. For Krook (Reference Krook2010), reflecting a broader consensus in the QCA community, the use of interaction terms in regression is not an acceptable substitute for the configurational logic of QCA, a rationale often used by critics of QCA who argue correlational analysis does the same job as configurational methods.

Potential Paths to GEF Success

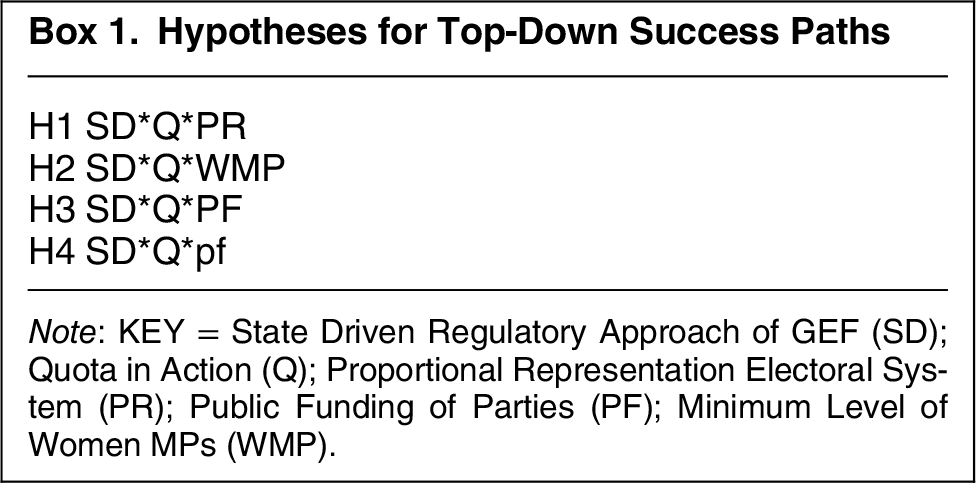

This section turns to the configurational hypotheses about GEF implementation success to be assessed in the mixed methods analysis of the 31 elections. While the literature identifies many different conditions that can potentially combine with GEF implementation to significantly enhance gender balance in legislatures, the QCA conducted here focuses on the potential combination of six of these conditions.Footnote 5 The reasons for omitting other important conditions are discussed at the end of this section. As previous research indicates and is shown in greater detail below, it is the presence or absence of each condition that counts in successful outcomes rather than gradated levels of each condition. Therefore, crisp set QCA is more appropriate to be used with distinct cutoffs established for “presence” and “nonpresence,” rather than fuzzy set or multivalue QCA.Footnote 6 The six conditions, expressed in crisp set logic, where capital letters indicate presence and small letters absence, include whether GEF is state-driven or not (SD/sd), whether there is a quota in action at the time of GEF implementation (Q/q), whether there is a PR electoral system in place or not (PR/pr), whether there is centralized candidate selection or not (CCS/ccs), whether political parties are publicly funded or not (PF/pf), and whether there is a 15% minimum level of women members of parliament or not (WMP/wmp). The configurational hypotheses for success are presented first for top-down state-driven instruments (Box 1) and then for bottom-up mechanisms developed in society or parties (Box 2). The specific operationalization of each condition, as well as the omitted conditions discussed below, can be found in the codebook in online Appendix 1, which also includes the source literature used for coding.

Box 1. Hypotheses for Top-Down Success Paths

Note: KEY = State Driven Regulatory Approach of GEF (SD); Quota in Action (Q); Proportional Representation Electoral System (PR); Public Funding of Parties (PF); Minimum Level of Women MPs (WMP).

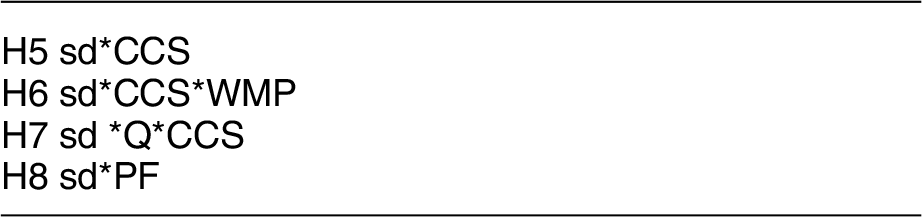

Box 2. Hypotheses for Bottom-Up Success Paths

Note: KEY = State Driven Regulatory Approach of GEF (SD); Quota in Action (Q); Proportional Representation Electoral System (PR); Centralized Candidate Selection (CCS); Public Funding of Parties (PF); Minimum Level of Women MPs (WMP).

While the presence of a state-driven GEF may determine the overall approach, it is not always part of a successful path. As Lépinard (Reference Lépinard2016) for France and Espírito-Santo (Reference Espírito-Santo, Lépinard and Rubio-Marín2019) for Portugal find, parties that spearhead the adoption of GEF measures may not comply, either due to lack of commitment to authoritative policies or because feminist activists who see the policies as half measures do not hold political parties’ feet to the fire. Given that much research asserts that quotas are important in promoting gender balance in representation and that an initial comparative study of GEF finds that having a quota in place is a sufficient but not necessary condition for increased gender balance (Muriaas, Wang, and Murray Reference Muriaas, Wang, Murray, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020), it is crucial to include quotas as a condition in combination with state-driven GEF.Footnote 7 In France and Ireland, for example, financing through state-driven instruments is used as a remedy to penalize parties that do not comply with a gender quota by reducing the amount of funding for parties that do not pass the threshold (Achin et al. Reference Achin, Lévêque, Durovic, Lépinard, Mazur, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020; Buckley and Gregory Reference Buckley, Gregory, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). Although they may be administratively connected, as in France and Ireland, GEF measures operate independently from any gender quota and thus are conceptualized here as two distinct instruments. As shown in Box 1, all four hypotheses for top-down paths to success include a quota in action combined with state-driven instruments, even though quotas are not always present in all top-down GEF. Research shows that these two conditions need to combine with at least one other condition to facilitate successful outcomes. Different options are plausible.

The first option includes the presence of proportional representation electoral systems (H1). Many comparative studies have shown the importance of PR for increasing women’s representation, but the studies also find that women’s increased representation does not occur in all PR systems (Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1996; Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1989; Sawer, Tremblay, and Trimble Reference Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006; Tremblay Reference Tremblay and Tremblay2012). The presence of multimember districts in PR systems has the potential to reduce resistance to GEF because influential men party members may still be placed in winnable seats even when the party complies with the threshold of women candidates needed to receive a payment or avoid a penalty. While there are a range of different types of PR systems, what is at play is that compliance to place women candidates on lists is easier to manage in multimember districts than in single-member districts in first-past-the-post electoral systems; thus, the crisp set logic of the presence or absence of PR makes empirical sense.

A second option brings in a third condition developed specifically for this study, a 15% minimum of women MPs (H2). Krook’s (Reference Krook2010) study of the different pathways to enhanced women’s representation specifically identifies “women’s status in politics” as a crucial ingredient for success. Others have focused on the importance of feminist coalitions, called strategic partnerships and triangles of empowerment, between women’s policy agencies, women’s movements, and women MPs as being a key part of feminist agendas as well as being indicative of a broader acceptance of values about women’s rights and gender equality.Footnote 8 Early work on critical mass by Kanter (Reference Kanter1977) on “skewed groups” and Dahlerup (Reference Dahlerup1988) on “tilted groups” provide the conceptual foundation for this condition.Footnote 9 Both assert that with a minimum of 15% women in parliament women can begin to form alliances within and outside of parliament and change institutional culture. In addition, the presence of at least 15% women MPs in parliament indicates elite support for gender equality—Krook’s “women’s status in politics”—as well as providing a potential for strategic alliances and a guaranteed reserve of experienced women when there is a sudden demand for women candidates when GEF is put into action. Such a reserve of eligible women also helps the eligibility of political parties for financial rewards or to avoid a penalty for noncompliance.

The third and fourth options for which conditions combine with state-driven GEF and quotas include the presence and absence of public funding for political parties (H3 and H4), often the vehicle through which GEF is administered. While public funding has been identified as a key mechanism for achieving equality of competition (Van Biezen and Kopecký Reference Van Biezen and Kopecky2007), work on the gender effects of public party funding is quite limited (Ohman Reference Ohman2018). Nonetheless, the country-based studies do provide some insights. Research on top-down initiatives suggests that when public funding is significant for parties, the door is opened for fines to be given for noncompliance with a gender-balance target (Buckley and Gregory Reference Buckley, Gregory, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020; Achin et al. Reference Mazur, Lépinard, Durovic, Achin and Lévêque2020). Top-down strategies may also occur in countries with limited public support for campaigning or party activities. Thus, the absence of significant public funding is also likely to make the prospects of a reward more appealing for parties just as much as its presence (Feo and Piccio Reference Feo and Piccio2020a; Ohman Reference Ohman2018).

Bottom-up strategies, found in Malawi, the US, and other countries, take place when a state-driven GEF is absent, instead relying on initiatives from private actors like political parties, companies, NGOs, and individual actors. It is expected that bottom-up schemes may be less successful than top-down instruments given there is no official involvement or endorsement by state or political party officials, as is the case for political action committees for women in the US (Gichohi Reference Gichohi, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). However, research shows that top-down approaches fail as well, for example, in Portugal (Espírito-Santo Reference Espírito-Santo, Lépinard and Rubio-Marín2019) and in France (Lépinard Reference Lépinard2016), and that bottom-up approaches succeed, as in Malawi (Muriaas and Kayuni Reference Kayuni and Muriaas2014). Furthermore, directly targeting women aspirants or candidates as a group by reducing the campaign costs is often a response to failed attempts at establishing a legislative quota. As Box 2 indicates, there are four potential paths to bottom-up success.

The presence of centralized candidate selection (CCS) across all parties may make-up for the shortfalls of a bottom-up instrument (H5). Previous studies find that CCS favors women because party leaders can ensure compliance with a gender target with sometimes the help of a quota (Caul Reference Caul1999; Hinojosa Reference Hinojosa2012). Hinojosa (Reference Piscopo, Hinojosa, Thomas and Siavelis2021, 159) suggests that avoiding primaries or enforcing clear limits on primary spending could increase women’s access to political offices. Building on this, if women candidates are assured extra funding for campaigning in elections, this might be the needed incentive for party leaders in centralized nomination systems to select more women.

Centralized candidate selection may not make it alone as is indicated in Hypothesis 6. If there are few women in elected office, party leaders may struggle to identify women that they can nominate. Therefore, CCS in combination with the presence of a 15% minimum of women MPs, indicating a certain level of support for women’s status and rights and gender equality, may make-up for the weaknesses of a GEF instrument itself. One flaw of a centralized system is that there are limits to how well party leaders know what is happening on the ground because leaders depend on networks present in the party organization or networks of their representatives when incentivized to do so (Van Houten Reference Van Houten2009). Alternatively, a quota in combination with centralized candidate selection may contribute to successful outcomes (H7). In the absence of any sanction mechanism strengthening the quota or engagement from the government, parties with centralized candidate selection may be more able to manage a gender-balanced list; thus, a bottom-up GEF could provide the incentive needed to follow the imperative of a quota regulation.

Another enabler for successful bottom-up approaches may be the presence of public funding (H8). Studies that identify money as a barrier to political recruitment are often done in contexts where there is no public funding to political parties. In the absence of public funding, parties need to rely on the candidates being able to fund their own election campaigns, as is the case in Zambia (Wang and Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019). If public funding is available for political parties, this reduces the risk involved in selecting less affluent or less well-known candidates and trying out new women candidates, particularly if women candidates are self-funded and are obliged to ask for funding from party coffers.

What Was Left Out and Why?

The six conditions to be considered in the QCA are by no means the only factors identified by researchers that may combine with GEF implementation to enhance gender balance in representation. Here, the omitted factors are discussed including the rationale for their exclusion from the QCA, keeping in mind that they are taken into account in the causal mechanism case analyses below and should be considered in any future study of GEF.

Two major conditions were initially coded and considered for QCA: GEF target (candidate or party) and GEF as a party penalty rather than a payment. When the GEF target was included in a six condition QCA model, the limit for a population of 34 or less, extreme model ambiguity and failure to generate parsimonious explanations without contradicting simplifying assumptions resulted. In addition, the GEF target is more or less covered by the state-driven condition given that most of the candidate targeted instruments were non-state-driven and the party targets were state-driven. Whether GEF penalizes or provides payment as a condition is omitted given that less than one third of the cases have the presence of a party penalty, thus, not enough variation.

While feminist coalitions of state and society-based actors have been found to be crucial in promoting effective gender equality policy (e.g., Mazur Reference Mazur2002), given they mobilize around all cases of GEF implementation in the study, their presence or absence makes no difference in the outcome. Furthermore, the condition, 15% minimum of women MPs, allows for examining what might be the more essential part of feminist coalitions. The influence of international norms from extranational organizations like the UN, ILO, or EU, also identified as an important driver in gender equality policy (e.g., Zwingel Reference Zwingel2016), is present across all cases as well, except for the US, and thus is omitted from the QCA. The ideology of the majority party in power has also been considered important for gender equality policy with left-wing majorities often found to be the most supportive (e.g., Caul Reference Caul1999); however, for many new democracies in this study, the ideological right-left cleavage is not politically meaningful. Once again, the condition of a minimum of 15% women MPs may serve as a proxy for this omitted condition as well given that it indicates support for gender equality values in the political elite, which actually may be what is at play more than the presence of a left-wing majority. Finally, feminist institutionalists have shown path dependent dynamics or gender-biased norms established over a long period to be important obstacles to feminist change (e.g., Krook and Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011). In this study, gender-biased path dependency is a possible explanation for cases of failure; however, its influence can only be detected over time, not through the QCA, and only in countries that have more than one case of GEF implementation, Therefore, the question of path dependency can only be taken-up in the causal mechanism case studies.

The Sequential Multi-Methods Research Design

With the configurational hypotheses presented, it is now possible to carry out the qualitative comparative analysis. But QCA on its own only provides part of the picture, particularly given some of the weaknesses of QCA—limited to a snapshot in time—and for the crisp set variant—oversimplification of conditions. As Goertz argues,

For multi-methods researchers, showing a significant cross-case causal effect is not sufficient; one needs to show a causal mechanism and evidence for it. Demonstrating a causal effect is only half the job; the second half involves specifying the causal mechanism and empirically examining it, usually through case studies.

(Reference Goertz2017, 2)This study opts for a sequential (Creswell and Creswell Reference Creswell and Creswell2017) approach to mixed methods. It “nests” (Schneider and Rohlfing Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013) two causal mechanism country-based case analyses of the unfolding of GEF over a roughly comparable period—for France from 2002 to 2017 and for Malawi from 2009 to 2019—in a csQCA analysis of the population of 31 cases of GEF implementation in relatively stable democracies, presented in Table 1.

Table 1. GEF Implementation in 31 Elections in 17 Democracies by Approach

Note: Years indicate the first election in which GEF is implemented.

Since the mid-2000s, there has been an emerging literature on how to conduct causal mechanism process-tracing case analysis (e.g., George and Bennett Reference George and Bennet2004). The case analyses conducted here take a “minimalist” rather than a “systems” approach in which the “causal arrow between cause and outcome is not unpacked in any detail” (Beach Reference Beach2017). The minimalist approach allows the case studies to both confirm the findings of the QCA and to assess whether the omitted conditions play a role in the shift from failed to successful GEF implementation over time. In order to scrutinize dynamics over the long haul, the two country cases are selected from the countries where more than one case of GEF implementation occurs—Canada, Croatia, Italy, France, South Korea, the UK, and Malawi. The cases of France and Malawi present an opportunity to conduct “a most different systems” (Przeworski and Teune Reference Przeworski and Teune1970) comparison given that they differ on a variety of sociocultural dimensions while sharing the similar outcomes of enhanced gender-balance in national parliaments through GEF failures being turned into successes. The two countries also each represent the two different approaches to GEF implementation even if the approach in Malawi is not entirely bottom-up.

It is important to note, that the operational definition of GEF success for this study, as with the operational definitions for all of the conditions under consideration, is meant to “travel” (Sartori Reference Sartori1970) across different financing regimes and regions of the world to better take on board comparative work on electoral financing, democracy, and gender.Footnote 10 Following the good practice of concept traveling is particularly important in this study given the range of different political systems where GEF measures have been put into action.

GEF success is measured in terms of the percentage of women legislators elected, as opposed to candidates presented, due to the possibility for false positives and that many women candidates do not have the opportunity to win. This focus on women elected to office also reflects the concern for gender balance “by the numbers” at the center of scholarly work and more policy-driven action from NGOs, international bodies, and feminist actors (Childs and Dahlerup Reference Childs and Dahlerup2018). To be considered successful, GEF implementation must lead to a significant increase in the number of women MPs in the election immediately following implementation.

In this study, an increase in women MPs is considered significant—a “success”—when the increase is at least twice the average rate of change in women’s share of MPs in the elections prior to GEF implementation in a given country.Footnote 11 The rate for each country serves as a cutoff for success, reflecting the general policy approaches to gender quotas where a given ceiling for women’s presence is met or not; thus, crisp-set logic is particularly appropriate.

Making Gendered Electoral Financing Count: Expected and Unexpected QCA Findings

Taking first a cursory look at the population of 31 cases, shown in Table 1, top-down approaches are more successful than bottom-up. Success and failure do not automatically correspond with cultural context—both outcomes occur in all world regions, a finding confirmed by global studies of gender and representation (e.g., Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010). There is also no pattern of success or failure that corresponds with the timing of the policy process, suggesting that economic climate is not a crucial factor either, an observation already made by Krook (Reference Krook2010). An examination of the lineup of the six conditions for each of the 31 cases of GEF implementation, the required first-step of any QCAFootnote 12, confirms what the previous research had already found that there is no specific configuration or “path” of conditions that leads to successful or failed outcomes.Footnote 13 This causal complexity is reduced in the results of the minimization process.

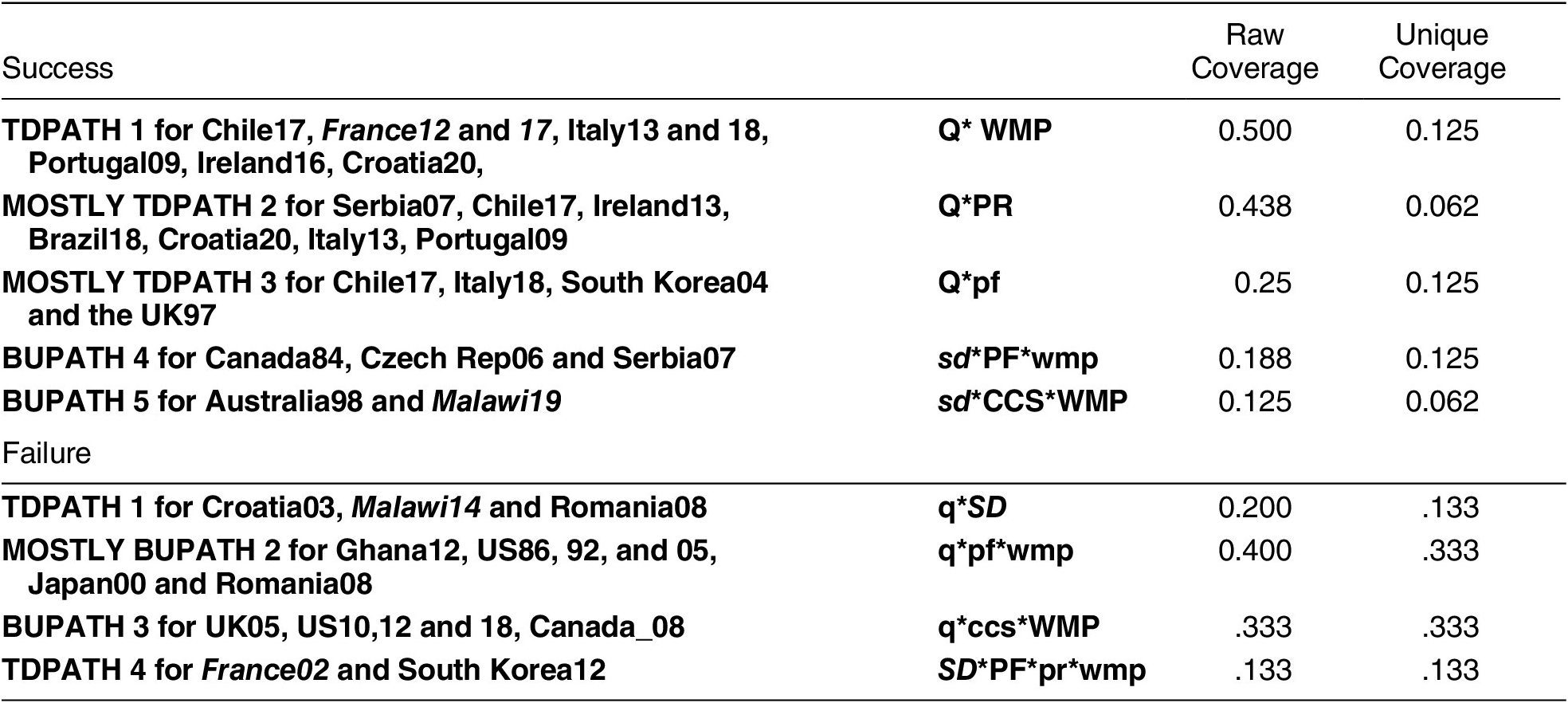

The parsimonious solution paths are presented in Table 2 for models derived for the [1] and [0] outcome with no contradictory simplifying assumptions. The country cases covered in each path are reported in column 1 and the combination of the presence or absence of conditions and the list of cases covered by each path in column 2. When a condition is not listed in the solution path, it means that neither its presence nor absence is important in the outcomes of the cases included in that path. Raw coverage, presented in column 3, indicates the share of all cases covered by a given path; unique coverage, the share of the total number of cases explained by that path only, are in column 4. Whereas some solution paths may cover substantially more cases, and thus are important for theory building or confirmation, solution paths that include fewer cases still play a role for understanding causality, particularly when a given path only includes those cases as in Success Path 5 and Failure Paths 3 and 4.

Table 2. Paths to Success and Failure for GEF Implementation

Note: KEY = TD = Top-down Approach: BU = Bottom-up Approach; State Driven Regulatory Approach of GEF (SD); Quota in Action (Q); Proportional Representation Electoral System (PR); Centralized Candidate Selection (CCS); Public Funding of Parties (PF); Minimum Level of Women MPs (WMP). Capital letters = presence of a condition; small letters = nonpresence.

Overall, there are nine different paths, five for success and four for failure. There is no single condition or combination of conditions in either their presence or absence that is a part of all paths of success or failure. Although a gender quota is present in all successful top-down paths, while the absence of a state-driven approach is present in all successful bottom-up paths. The absence of a quota also appears in three out of the four failure paths. In accordance with expectations, however, gender quotas cannot do it alone and there are also success paths where a quota is not present. Taking a deeper dive into the five success paths allows for a more precise understanding of GEF contributions to enhancing gender balance.

Quite strikingly, state-driven GEF instruments are absent in all success paths, which means that none of the expected top-down configurational hypotheses are confirmed. A simplified H1 (without SD) is supported, as the csQCA results show that 43% of all successful cases share a PR system in combination with the presence of a quota. This path is not entirely top-down, “mostly” TD in Table 2, as Serbia07 is a bottom-up case. Success path 1 is the only path that includes only top-down cases; the presence of a gender quota and a 15% minimum of women MPs prior to GEF implementation significantly increases women in legislative office for half of the success paths. There is some degree of a regional pattern for this path, which includes Chile and member states of the European Union. Therefore, perhaps the presence of quotas in a Western context is quite important for success. Also, all but the case of Portugal take place in the same recent time span, 2012–2020. The third two-condition success path is also mostly a top-down path with quotas found to be in play with GEF implementation to achieve success, but this time with the absence of any public funding for political parties for 1/3 of all cases and only 15% of the cases of success.Footnote 14 Regional diversity is quite pronounced, with successful cases from countries in South America, Western Europe, and East Asia. This path appears to also run against the expectation that the presence of public funding contributes to success (H3).

While all original top-down approach hypotheses were refuted or simplified—indicating less complexity than expected, the QCA results for bottom-up approaches are quite complex. While H5 (sd*CCS) and H7 (sd*Q*CCS) are rejected, there is support for H6 (sd*CCS*WMP), and for a more complex version of H8 (sd*PF *WMP). Bottom-up approaches are thus more complex than top-down strategies. For example, privately driven approaches with public funding are only successful when a 15% minimum of women MPs is absent. This is an important path, as the success in two of the three cases are only explained by this path. The question of public funding and a 15% minimum of women MPs is thus not a straightforward one, given that contrary to the first two paths the presence of public funding and the absence of a 15% minimum of women MPs combine with the implementation of a GEF scheme that is not state driven.

Looking at the three cases explained by this path, they occur in the first decade of the 2000s, quite early for GEF reform, in two countries having just undergone a transition to democracy, the Czech Republic (2006) and Serbia (2007), and in a third country known for its electoral volatility from one legislative election to another, Canada (1984). Therefore, this path appears to be salient in contexts where there is significant change in the composition of parliaments. The last bottom-up path to success is also a three-condition path, which was expected. This time the path only applies to the countries in the path, a quite analytically powerful finding, with two contrasting country cases, a postindustrial western country—Australia—and a developing Sub-Saharan country—Malawi—with the combination of a 15% minimum of women MPs and a non-state-driven GEF, bringing into the mix for the first time a centralized candidate system.

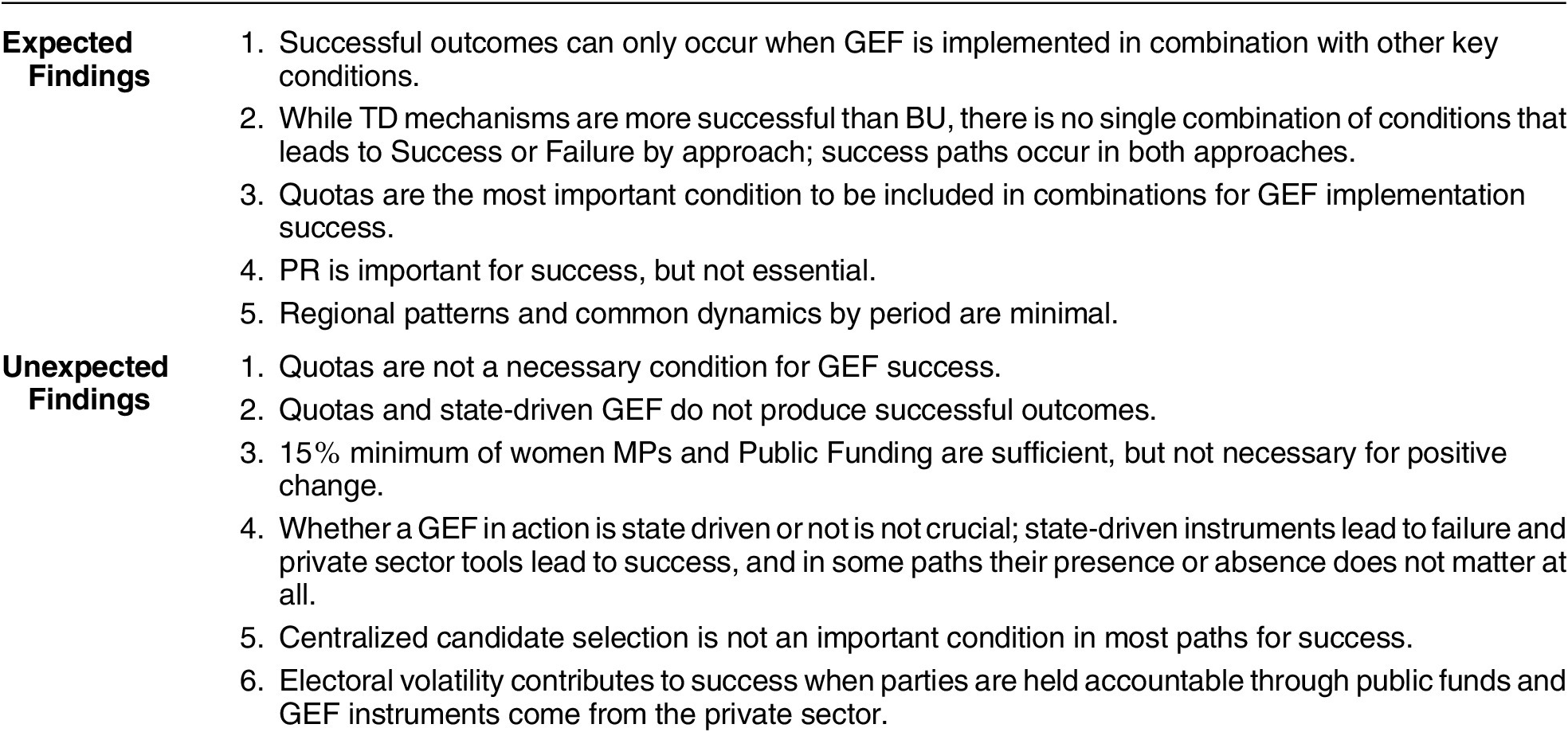

Putting it All Together So Far: Expected and Unexpected Results

The csQCA generated expected and unexpected findings, presented in Table 3, laying solid groundwork for the two causal mechanism cases studies presented in the next section, particularly given that Creswell and Creswell (Reference Creswell and Creswell2017) argue it is necessary to move from larger-n analysis to case studies when results are unexpected in mixed methods studies.

Table 3. csQCA Findings: Expected and Unexpected

Process-Tracing Case Studies: Turning Failure into Success in France and Malawi

To what degree do the expected and unexpected findings from the csQCA play out in the causal mechanisms at work in the two cases studies? Are any of the factors left out of the csQCA important for the transition from failed to successful GEF implementation in each country? These are the questions that drive the two “minimalist” process-tracing case analyses with a most different systems design.

A CLASSIC TOP-DOWN APPROACH IN FRANCE (2002–2017): Parity Penalties through State Feminist Alliances and a Minimum Level of Women MPs Incentivize Women Candidates and Party Leaders

In France, the state-driven GEF scheme has been implemented since 2002 in conjunction with constitutionally mandated quotas, called parity.Footnote 15 France had been renowned for low and stagnant levels of women MPs prior to 2002, going from 4% in 1978 and reaching only 10% in 1997. A large and vocal coalition of feminist groups joined with women’s policy agencies inside the cabinet and parliament, using policy pressure from the UN, EU, and the Council of Europe to convince the Socialist government to adopt a constitutional amendment in 1999. A separate law came soon after on the specific mechanism of the penalties in National Assembly elections; political parties were targeted through a reduction in their government funding in proportion to the percentage difference between men and women candidates presented in the first round of elections across all constituencies.

In the first election in 2002, the penalties had little effect given their low level. The larger parties chose to take the relatively low financial hit in government funding rather than present women candidates in half of the constituencies and the result was a failure. In a context without a minimum level of women MPs and their networks of eligible women, the party penalties were not a strong enough incentive for party leaders to change their behavior. A 2007 law, adopted under the right-wing government, through the same coalition of feminist forces behind the parity reforms, although this time without any extra national influence, increased the level of the party penalty to 75%, and it was applied in the 2012 June parliamentary elections, with women winning 27% of the seats. In 2014, the powerful Ministry of Women’s Rights and Equality convinced the Socialist government to increase the fines one more time to 150% of party grants. In the 2017 legislative elections, women received 38.7% of seats in the National Assembly, an all-time high in France and a 28% increase since the parity sanctions had been implemented, but still 12% from the goal of numerical parity.

The increase clearly incentivized party gatekeepers to assure that women were selected for winnable seats. The steady rise of women MPs above the minimum level of 15% meant that more women were encouraged to run for office as well. The 2017 elections provided an unprecedented context for success. A new reform that limited individuals from holding more than two elected offices opened incumbent seats in the National Assembly for women newcomers, and the landslide victory of Emmanuel Macron’s new party paved the way for more women MPs given that the party had followed 50-50 parity in candidate selection. While it is difficult to parse out the effects of the reforms and the Macron landslide from the increase in penalties, the wide elite acceptance of parity indicated by the spread of “parity grammar” (Bereni and Revillard Reference Bereni and Revillard2007) and the increasing presence of women MPs certainly played an important role in the significant rise. Despite these successes, research has shown persistent gender biases; women are ignored when seats are in clearly winnable districts and women MPs continue to be kept away from positions of power and influence.

COMPLEXITY WITHOUT QUOTAS IN MALAWI (2009 to 2019): Feminist Mobilization and Women MPs Incentivize Women Candidates and Party Leaders

Failure of GEF implementation in the 2014 Malawi election was turned into success in 2019. What are the mechanisms that explain why a new type of GEF introduced prior to the 2019 was more successful? In Malawi, there has been constant engagement with trying to develop a GEF design without a legislated quota or a PR electoral system. The first GEF initiative was launched prior to the 2009 elections, as donors and domestic women’s organizations were concerned about the 87% share of male MPs. A 50:50 Campaign, with a parity goal and funded by donors, gave cash funds and other resources to women to facilitate their electoral campaigns. However, the role of the government was unclear, and elections were not completely free. The 50:50 Campaign was continued in the two following elections. The Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability, & Social Welfare coordinated the campaign in 2014. The president, Joyce Banda, appointed after Bingu wa Mutharika died in office, initiated several gender reforms and had a particular interest in the continuation of the GEF scheme (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Kayuni, Chiweza, Soyiyo, Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). As is typical for the region, it is difficult to place Malawian parties on a left–right spectrum. In 2014, the implementation of the more top-down approach targeting women candidates resulted in failure, and the strong ties between a government and the GEF initiative were seen to be problematic. Joyce Banda, implicated in a corruption scandal, lost her bid for reelection and the poor election results for women were seen as a spillover effect of dissatisfaction with her performance (Kayuni Reference Kayuni, Banik and Chinsinga2016).

The top-down approach was also discredited; thus, for the 2019 election an NGO, the 50:50 Management Agency, took over the organization of the campaign in which political party leaders were more willing to participate. This time, its main funder, the Norwegian Embassy, collaborated with the management agency to reimburse the registration fees of women candidates. Parties also took an interest in the scheme because they did not have to pay the fee for women candidates (Malawi News, February 16–20, 2019). The situation was a win-win: the constituency branches did not pay registration fees for women, and party leaders could attempt to comply with calls to advance gender-balance. The combination of an independent agency in charge of GEF and that not only party leaders but also regional and local branch leaders were incentivized to select women, encouraged more women to step up as well. The newcomers had seen that other women had been successful in the past, thus showing that a 15% minimum level of women MPs prior to the implementation of a GEF was an important contributing factor. In all, Malawi can be seen as both a top-down and bottom-up success story, as the influence of GEF grew when there was a stronger demarcation between the government and the initiative.

Analytical Implications

So, what were the causal mechanisms behind failures being turned into success in the two countries? In both countries, this development occurred without PR, but with the incentives of GEF mechanisms, reduced costs for parties and women candidates in Malawi without a quota and increased costs to political parties for noncompliance with the parity quota in France. Another contributing dynamic in both countries was the presence of a 15% minimum of women MPs, which indicated the previous success rates of women candidates and party willingness to mobilize women’s networks. Feminist alliances were also instrumental in putting the GEF schemes in place and making sure they were implemented as well as evolving gender norms that represented critical junctures in gender-biased path dependencies. Despite the similar outcomes, the impetus and arena for the successful turn of events in both countries were quite different. In France, the legal restriction through penalties was a result of state feminist-based alliances and was implemented by the national administrative process through the public funding of the political parties. In Malawi, international donors funded a bottom-up process with feminist NGOs trying to keep the government at a distance through positive attention through payments that boosted the financial advantage of women candidates. Whether the GEF was targeted at parties or candidates made little difference in moving failure to success in either country.

Conclusions

The mixed methods analysis has paved the way for a fresh look at the struggle for gender-balanced representation through a focus on the potential efficacy of different financial policy instruments—gendered electoral financing. Whereas the implementation of GEF schemes cannot succeed alone, it can provide the needed incentive for both party leaders and eligible women to change their behavior when they are combined with key conditions. Thus, this study advances work on gender and representation not only by putting a new effective instrument on the radar for positive change but also by empirically showing the combinations of conditions that contribute to decreasing the gender democratic deficit. While the lineup of ingredients for success are complex, the integrated results indicate the following conditions and contextual settings that are NOT critical for enhanced gender representation when GEF is put into action:

-

• centralized candidate selection,

-

• the target of GEF (party or candidate),

-

• the regional location of a given country,

-

• the particular period and economic climate,

-

• the level of economic development,

-

• a state-driven GEF in place, and

-

• a PR electoral system.

Top-down and bottom-up approaches both work, yet top-down approaches are more successful and less complex. The two causal mechanism case studies confirm the findings of the QCA that a 15% minimum of women MPs is quite important for success, but not necessarily in combination with a quota, a state-driven GEF, or public funding of parties. The experiences of France and Malawi also indicate that important progress can be made in the struggle for gender balance without PR. Given the differences in approach in the two countries with similar successful outcomes, the right question to ask is not always whether a top-down or bottom-up approach is taken but whether and how the design and the conditions are effective under a certain set of circumstances.

In terms of the factors omitted in the csQCA, the mobilization of feminist alliances, either at the grass roots level or within the state, contributed to turning failure into success in both Malawi and France, but their efforts were facilitated by the presence of a minimum level of women representatives. Moreover, given that feminist coalitions always participate in GEF implementation, it appears to be the way feminist alliances mobilize around implementation that matters more than if those coalitions are simply present. International influence on the policy process is almost always relevant at some stage of the process, in Malawi more than in France, thus not necessarily crucial to success. The extent to which the reduction of gender-biased path dependencies was important to progress in both France and Malawi confirms what the QCA results showed, that a continued 15% minimum of women MPs signaled a turn away from the past gender-biased norms of political party leadership in successful elections in the mid-2000s. The country case analyses confirmed that it was not an artifact of the QCA process that GEF target and the authority were left out: neither the target of the instrument nor whether it was a carrot or a stick were important in enhanced gender balance. Whereas concerns for conceptual stretching prevented the inclusion of the influence of party ideology in the QCA, the French case study indicates that the majority in power makes little difference in the practice and effects of GEF. Furthermore, the new condition of a 15% minimum of women MPs accounts for what may be at stake when considering the presence of left-wing majorities—support for gender-equality among the political elite.

To be sure, while this study provides meaningful new insights, there is still much work to be done. A multilevel research agenda should be followed through examining the effects of GEF implementation at all levels of elections in democratic and nondemocratic countries. The influence of GEF on substantive representation of women in terms of both process and outcomes is also a promising avenue for future research by shedding light on whether women who enter office as a result of GEF seek to represent women’s interests. Here, a microfoundational approach would be important through delving into how individual actors and coalitions mobilized, or not, around GEF. As the French case study indicates, future studies might focus on issues of quality of representation, whether women once elected hold positions of power and whether they are able to get reelected. Designing a study that examines the electoral fortunes of women in countries without GEF compared with countries with GEF is an important next step in the GEF research cycle as well, one that would bring in large-n correlational analysis and thus enhance methodological diversity.

The successes and failures of the worldwide diffusion of gendered electoral financing has provided a unique opportunity to improve knowledge about the intersection of gender, political rights, and economic inequalities and to bring new insights into broader questions of the influence of wealth and status in politics that stand to nourish concrete action taken to decrease that very influence. An important missing link between scholars of democracy and of gender and politics has been made through a clearer articulation of the close connections between economic and gender inequality. Studying GEF provides a lens into understanding how funding incentivizes political behavior in terms of scholarly and policy considerations. Indeed, the following observations and policy recommendations coming out of the study have the potential to help policy actors, practitioners, and activists in the ongoing struggle for gender balance across the globe:

-

• Progress can be achieved in any type of electoral system as long as other favorable conditions are present.

-

• Adopting a state-driven instrument is not as important as getting at least 15% women elected to national office; incremental increases in women’s representation can actually make a difference.

-

• Quotas do not necessarily need to be in place, but they can help; GEF targeted at individuals or parties can go it alone with the right combination of conditions.

-

• Women can get elected without public funding, particularly when candidate selection is centralized.

-

• Progress can be made in a variety of political contexts, cultural settings, and economic climates.

This study has hopefully demonstrated that democracy has not entirely failed women. What works and what does not is the province of not only those who are uniquely interested in women’s representation but also anyone who is interested in how to promote more healthy, inclusive, and open democracies. As money plays a vital role in determining access to political institutions and power, using financial mechanisms to incentivize the selection of women candidates is a powerful tool for increasing access for the underrepresented in politics. Moreover, this study highlights that the selection of appropriate financial instruments must be done with careful consideration of context and the specific conditions that can block success. In the final analysis, money does matter in politics. Actors do change their behavior when streams of funds are redirected, but context must be carefully considered for success to be achieved.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000976.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials for this study are available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VZZBHE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An earlier version was presented at the Roots of Political Inequality workshop at the Centre Universitaire de Norvège à Paris. Deep gratitude goes to Vibeke Wang, Gary Goertz, Anne Rasmussen, Jan Rosset, Jana Belschner, Nathalie Giger, Mia Costa, Yvette Peters, Happy Kayuni, Asiyati Chiweza, Einar Berntzen, and Ligia Fabris Campos for their crucial help. Special thanks go to the editors and reviewers for the priceless feedback that reflected a deep and much-appreciated methodological, theoretical, and empirical expertise and an unusually close and careful reading of all versions of the manuscript.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The research for this paper was funded in part by Norges Forskningsråd [grant number 250669/F10].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.