Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

In 1959 a number of progressive Democratic congressmen organized the Democratic Study Group (DSG) as a vehicle for countering certain conservative biases then present in the decision-making process in the House of Representatives. This paper presents brief descriptions of the difficulties faced by these congressmen in their efforts to pass more “liberal” legislation and of the organization and activities of the DSG. The analytical focus is on an assessment of DSG success in developing an effective communication network as a means of achieving its policy goals. The central hypothesis is that this communication network has had an impact on the voting behavior of DSG members. Roll-call data from the 84th through the 91st Congress are examined to ascertain whether longitudinal patterns in the voting of DSG members, non-southern non-DSG Democrats, southern Democrats, and Republicans tend to confirm or deny this hypothesis.

We wish to thank the Inter-University Consortium for Political Research for providing the roll-call data used in the analysis.

1 Stevens, Arthur G. Jr., “Informal Groups and Decision-Making in the U.S. House of Representatives,” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1970)Google Scholar; Matthews, Donald R. and Stimson, James A., “The Decision-Making Approach to the Study of Legislative Behavior,” (paper delivered at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, 1969)Google Scholar; Saloma, John S. III, Congress and the New Politics (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1969), pp. 214–218 Google Scholar.

2 Stevens, pp. 58–59.

3 Matthews and Stimson, pp. 18–19.

4 The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 contained a provision that requires all committee reports to be printed and available three days (excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays) prior to floor consideration. Furthermore, it also stipulates that Appropriations Committee hearing transcripts be similarly available.

5 See Saloma, , Congress and the New Politics, pp. 210–211 Google Scholar and the sources cited therein.

6 Democratic Study Group, Special Report, July 7, 1970.

7 Hinckley, Barbara, Stability and Change in Congress, (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), p. 80 Google Scholar.

8 The two best sources on the formation and early development of the DSG are Kofmehl, Kenneth, “The Institutionalization of a Voting Bloc,” Western Political Quarterly, 17 (06, 1964), 256–272 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Ferber, Mark F., “The Democratic Study Group: A Study of Intra-Party Organization in the House” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1964)Google Scholar. A more recent discussion and analysis of the effectiveness of the DSG is an excellent unpublished paper by Henderson, Anne: “The Democratic Study Group: An Appraisal” (Rutgers University, 1969)Google Scholar.

9 In subsequent analysis we utilize the whip lists to identify DSG members. Special thanks are due Richard Conlon, Staff Director of the DSG, for providing these lists as well as numerous other bits of information and insight.

10 Bibby, John F. and Davidson, Roger A., On Capitol Hill: Studies in the Legislative Process, (Hinsdale, Ill.: Dryden Press, 2nd ed., 1972), chap. 8Google Scholar.

11 Ferber, chap. 4.

12 Davidson, Roger H., Kovenock, David M. and O'Leary, Michael K., Congress in Crisis: Politics and Congressional Reform (Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1966)Google Scholar; and Bibby and Davidson, chaps. 4 and 8.

13 The interviews were obtained by Warren E. Miller and Donald E. Stokes as part of their study of the linkages between public opinion and congressional rollcall behavior. See Miller, and Stokes, , “Constituency Influence in Congress,” American Political Science Review, 57 (03, 1963), 45–56 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

14 The 1969 interviews were conducted by Arthur G. Stevens, Jr., as part of his research for the dissertation cited above. The 1971 interviews with numerous congressional staff members, DSG members and leadership, as well as some Republicans, were gathered purposely for this paper.

15 Nonuanimous roll calls were defined as those roll calls on which at least 10 per cent of the House members voted in opposition to the majority. The sample was drawn so that the number of roll calls selected is proportional to the output of the congressional committees.

16 See Stevens, and see also Miller, Arthur H., “The Impact of Committees on the Structure of Issues and Voting Coalitions: The U.S. House of Representatives, 1955–1962” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1971)Google Scholar.

17 MacRae, Duncan Jr., Issues and Parties in Legislative Voting (New York: Harper and Row, 1970)Google Scholar; and Weisberg, Herbert F., “Dimensional Analysis of Legislative Roll Calls” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1968)Google Scholar.

18 The correlation coefficient used is the tetrachoric r, a measure of association that indicates the degree to which variables share a common dimension. For an excellent discussion of tetrachoric r and its applicability to dimensional analysis, see Weisberg, chap. IV, and MacRae, chap. 3.

19 The factor analysis was done with unities as the estimate of the commonalities, and an orthogonal (varimax) rotation was used to obtain the matrix of factor loadings. The solution from the orthogonal rotation was selected as optimal, since the factors were found to be uncorrelated in the oblique solution. Furthermore, the varimax solution gave the clearest pattern of loadings, i.e., an item has one large loading with much smaller remaining loadings.

20 Variance terminology is not strictly appropriate for the factor analysis of dimensioning coefficients since such coefficients are not based on the statistical concept of covariance. The factor contributions, however, which are equal to the sum of the squared loadings for each factor, can be used as a rough measure of the relative importance of the factors.

21 The matrix of factor loadings resulting from the factor analysis of the tetrachoric r matrix is used to compute the factor scores. The actual computation of the scores is based on the estimation procedure suggested by Harmon, Harry H., Modern Factor Analysis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 348–350 Google Scholar. When factor analyzing tetrachoric r, a factor loading of unity means that the roll call falls exactly on the dimension indicated by the factor. A loading of minus one means that the item needs to be reflected (i.e., the scoring reversed) to be positively correlated with the other items on the dimension. The size of the loadings does not indicate order of the items on the dimension, only that they share a common dimension. The overwhelming majority of loadings obtained in the analysis were .8 or larger in magnitude.

22 The computational formula for the squared distance between any two points in an n dimensional space is:

where n is the number of dimensions (of factors), and x and y are the two different points. When mean factor scores are used to compute the distance between groups, the mean values can be readily substituted in the equation for x and y.

23 One alternative hypothesis would attribute cohesion to constituency similarity. Unfortunately, attempting to control explicitly for constituency factors would increase the complexity of the analysis far beyond the possible scope of this report.

24 For a more detailed explication of the measurement problems surrounding predispositions and some approaches to a solution, see Stevens, , “Informal Groups and Decision-Making in the U.S. House of Representatives,” pp. 42–46 Google Scholar.

25 These data are taken from Anne Henderson, “The Democratic Study Group: An Appraisal,” Appendix F. The author's unique position on the Hill allowed her to discern the level of DSG involvement on a set of roll call votes in the 88th–90th Congresses. She used a quasi-experimental design to study cohesion as well as turnout, and her findings on the former are generally in accord with those reported in this paper.

26 The computation of the mean interpoint distance was accomplished by using the group mean on each factor as the axis location for the group; from these axis values the squared Euclidean distance between each group was obtained. (See note 22 for the formula used to compute the distance.) As the similarity in the voting behavior of the two groups increases, the distance increases. If the members of the two groups vote exactly the same on all the bills, the distance between the groups would be zero. As the two groups grow increasingly opposed to each other, the distance value also increases.

27 Future DSG members are identified as those Democratic congressmen who signed the Liberal Manifesto. For a description of that document, see Kofmehl, pp. 258–260.

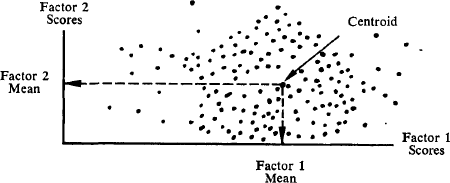

28 The centroid is simply the center of the group within the hypothesized geometrical space defined by the several factors. It is found by using the mean factor scores for the group as axis projections. For example, if two factors are used, we may represent the centroid as follows:

The factor scores for each individual member (represented as a point in the two-dimensional space) are used as axis projections in computing the squared Euclidean distance of the individual from the group centroid. The standard deviation of the distribution of distances from the centroid is used to define the different levels of group involvement.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.