When, and under what circumstances, are congressional minority parties capable of influencing legislative outcomes? This question is in need of further investigation for at least two reasons.

First, we know that minority parties sometimes exercise significant influence over legislative outcomes, but we lack robust explanations for when, why, or how. For example, despite unified Republican control of the White House and Congress in 2018, the $1.3 trillion omnibus spending package enacted that March not only needed Democratic votes to pass but also contained numerous Democratic Party priorities—including significant investments in child care programs, health care funding, election security, and more. As White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney put it, “we had to give away a lot of stuff that we didn’t want to give away.”Footnote 1 On final passage, the bill had as much Democratic (60% of the caucus) as Republican (62%) support in the House and more support from Democrats (39) than Republicans (25) in the Senate.Footnote 2

Several empirical findings underscore the often unexpected influence of minority parties: Majorities frequently need minority party support to pass major legislation (Curry and Lee Reference Curry and Lee2020) and minority party support for a bill in committee is predictive of its legislative success (Ryan Reference Ryan2020). House minority parties shape the issue attentions of the majority party (Hughes Reference Hughes2018) as well as the floor roll-call record (Egar Reference Egar2016). Majority parties are often unable to control the House floor agenda (Ballard and Curry Reference Ballard and Curry2020), and there are virtually no differences between the negative agenda-setting powers exercised by House and Senate majority parties, despite far more favorable rules in the House (Ballard Reference Ballard and Curry2021; Gailmard and Jenkins Reference Gailmard and Jenkins2007; Reference Gailmard, Jenkins, Monroe, Roberts and Rohde2008). Meaningful minority party influence is not a rare occurrence.

Second, the nature of the American constitutional system compels us to better understand the influence of minority parties. The founders placed an emphasis on minority rights when designing the U.S. Constitution. While they were not thinking of minority parties, they nevertheless set up a governmental system that was intended to frustrate majorities (Hamilton, Madison, and Jay Reference Hamilton, Madison and Jay2003). Today, the American hybrid system is as much consensus based as it is majoritarian (Dahl Reference Dahl2003; Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012), and it frequently hinders the policy ambitions of majority parties (Carey Reference Carey2007; Curry and Lee Reference Curry and Lee2020; Mayhew Reference Mayhew2005; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992).

Despite these compelling reasons, scholars and observers of Congress offer no consistent explanations for minority party influence. Observers often chalk up minority influence to failures on the part of the majority or the majority leadership.Footnote 3 Scholars have focused overwhelmingly on understanding majority party power (e.g., Aldrich and Rohde Reference Aldrich, Rohde, Bond and Fleisher2000; Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Curry Reference Curry2015; Monroe and Robinson Reference Monroe and Robinson2008; Roberts Reference Roberts2005; Roberts and Smith Reference Roberts and Smith2003; Rohde Reference Rohde1991). Left relatively underexplained are the underpinnings of minority party influence. As a result, examples of minority party influence like those noted above are not well explained by prominent theories of party power.

Here, we develop a theory of minority party capacity for legislative influence. By capacity, we mean the ability to influence legislative outcomes. We argue that the capacity of minority parties is a function of three factors: (1) constraints on the majority party, which create opportunities for the minority; (2) minority party cohesion on the issue at hand; and (3) motivations for the minority to engage in legislating rather than electioneering. As these factors increase and align, a minority party’s capacity increases.

We test our theory by developing original measures representing each of these three factors and with data on every bill introduced in the House of Representatives from 1985 to 2006 (Ballard and Curry Reference Ballard and Curry2021).Footnote 4 We present several analyses. First, a particularly difficult test: predicting the content of the House floor agenda, an aspect of congressional politics typically understood to be entirely controlled by the majority party (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). We find that bills dealing with issues where minority party capacity is greater are more likely to be considered on the House floor. Second, we show that our theory also helps explain downstream legislative outcomes: minority party capacity predicts which bills become law. Finally, we present several case examples that demonstrate the value of our theory for explaining minority party influence over lawmaking outcomes and the substance of policy, including cases not well explained by existing theories focused on majority party power. Altogether, our findings have important implications for our understanding of party influence and the balance of majority and minority power in Congress.

Limited Understanding of Minority Party Influence

Most research on congressional action focuses on the influence of majority rather than minority parties. Scholarship that does focus on minority parties largely falls into three categories. The first is scholarship that attributes the minority party’s influence to its control over specific legislative procedures or veto points (e.g., Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1998; Krehbiel, Meirowitz, and Wiseman Reference Krehbiel, Meirowitz and Wiseman2015). In other words, the minority party is typically thought to have legislative capacity because it almost always controls the filibuster “pivot” in the Senate (Evans and Lipinski Reference Evans, Lipinski, Dodd and Oppenheimer2005) and the president’s veto during divided government (Cameron Reference Cameron2000; Conley Reference Conley2002). This scholarship, however, provides limited insight into when and how minority parties have influence independent of these veto powers.

A second category focuses on minority party tactics (e.g., Egar Reference Egar2016; Hughes Reference Hughes2018). However, this scholarship largely does not seek to understand influence over legislative outcomes. For instance, Jones (Reference Jones1970) characterizes minority parties of different eras and their approach to congressional politics but does not attempt to assess how or when minorities use their leverage to achieve policy ends. Connelly and Pitney (Reference Connelly and Pitney1994) study the Republicans’ long stretch in the House minority, from 1954 to 1994, detailing in-fighting within the GOP over tactics. However, they do not attempt any general theorizing about legislative influence. Green (Reference Green2015) and Lee (Reference Lee2016) provide impressive insight into the strategies of congressional minority parties, but neither study intends to assess the influence of those tactics on specific legislative outcomes. As Green (Reference Green2015, 5) puts it, his study considers “ … only the short-term, proximate consequences of select instances of minority party action.”

A third category examines minority party influence on legislative outcomes based on variation in institutional arrangements across American legislatures. Clark (Reference Clark2015), for instance, provides an impressive look at how legislative resources and the dispersion of institutional prerogatives in the 50 state legislatures and Congress interact with levels of party polarization to create different costs and opportunities for minority party influence. Yet this institutional focus downplays the integral role of intraparty cohesion in party politics (Aldrich and Rohde Reference Aldrich, Rohde, Bond and Fleisher2000; Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005).Footnote 5 Further, such studies use aggregate measures of party polarization, which mask considerable variation in preferences on different issues (Crespin and Rohde Reference Crespin and Rohde2010; Jochim and Jones Reference Jochim and Jones2013).

Consequently, our understanding of minority party capacity in Congress is lacking in several ways. For one, we lack an understanding of variation in minority party influence from bill to bill or issue to issue. We sometimes see minority party members and leaders exercise substantial influence over a legislative outcome, but at other times the minority party appears sidelined. Consider, again, the minority Democrats’ substantial influence over the March 2018 appropriations omnibus package. Compare this with the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, which passed just a month prior over the opposition of the Democratic leadership and two thirds of the party and reflected few Democratic priorities.Footnote 6 Why were the minority Democrats able to exercise substantial influence over one bill but not the other? Both were spending bills that included numerous nonappropriations riders. Both were considered against the possibility of a government shutdown. Both happened during unified Republican government, within nearly identical political and procedural contexts, and just one month apart. More insight is needed.

We also have limited understanding of why minority parties sometimes exercise influence during the earliest stages of the legislative process. Majority parties do not need minority party votes to report bills out of committees or to pass legislation on the floor of the House of Representatives. Although party leaders sometimes consider the super-majoritarian requirements of later stages of the legislative process, these are not immediate concerns for setting the chamber agenda (see Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Den Hartog and Monroe Reference Den Hartog and Monroe2011). Indeed, majority parties sometimes seek minority party buy-in during the earliest stages of the legislative process (Balla et al. Reference Balla, Lawrence, Maltzman and Sigelman2002; Ryan Reference Ryan2020); at other times the majority pushes bills through these initial stages without minority party support. Curry and Lee (Reference Curry and Lee2020) describe choices made by majorities to pursue either a partisan strategy, “backing down” as necessary later, or a strategy of “building broad support” and including minority party input from the start. We lack understanding of this variation from case to case.

While existing studies of minority party capacity provide us with a foundation for understanding minority party influence, more insight is needed to understand when, why, and to what extent minority parties influence legislative outcomes.

A Theory of Minority Party Capacity

We argue that minority party capacity in Congress is a function of three factors: constraints on the majority party, which create opportunities for the minority; minority party cohesion on the issue at hand; and the minority party’s motivation to engage in legislating rather than electioneering. Each factor might independently affect the capacity of minority parties, but it is the confluence of the three that results in the greatest capacity.

Opportunities from Constraints on the Majority

First, the capacity of congressional minority parties is affected by the political and policy constraints on the majority party, which can create opportunities for the minority party to exercise influence. Congressional majority parties enjoy clear procedural advantages over minority parties. House majority parties almost always possess a procedural monopoly capable of organizing the chamber and settings its legislative agenda (Cox and McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins2005).Footnote 7 While minority parties in the Senate benefit from super-majoritarian debate and cloture rules, majority parties are still able to exercise substantial agenda control (Den Hartog and Monroe Reference Den Hartog and Monroe2011) and have some tactics at their disposal to side-step these super-majoritarian requirements (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2017). Simply, minority party capacity is greater when the majority is more constrained in its willingness, or in its ability, to leverage its procedural advantages into substantive outcomes.

Constraints on the majority stem from several sources, including the dynamics of party control in Washington. Majority parties facing divided government by definition must be more attentive to the minority party’s legislative priorities than those enjoying unified control. Parties with smaller chamber majorities are also more constrained, with less room for error in building intraparty unity. Majority parties may also sometimes see electoral value in cultivating bipartisanship, in other words, coopting the support of the minority for electoral purposes (Balla et al. Reference Balla, Lawrence, Maltzman and Sigelman2002; Harbridge and Malhotra Reference Harbridge and Malhotra2011; Lee Reference Lee2016).

Issue to issue or bill to bill, however, the degree to which the majority is constrained is perhaps most affected by the level of (dis)unity within the majority party. Bills or policies on which the majority party is more unified need less support from the other side of the aisle to advance. Unified House majority parties, for instance, do not need any minority party support to advance bills in committee or on the floor. Unified Senate majorities typically still need some minority party support (i.e., to overcome filibusters), but they need less of it compared with when the majority party is divided. When the majority lacks cohesion, finding itself internally divided on an issue, more minority party support is simply necessary to move legislation forward. With fewer votes assured from the majority’s side, more will need to come from the other side. This creates opportunities for the minority party.

Some prominent theories of congressional majority party power argue that the majority will simply not consider legislation that internally divides it (e.g., Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). However, majority parties do not have complete discretion over the issues on the agenda. Some legislation is compulsory, or “must-pass” (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013) including appropriations bills, debt ceiling bills, tax extender bills, and many—though not all—reauthorization bills. These compulsory items are not a small share of the agenda. Indeed, Adler and Wilkerson (Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013, 123) estimate that compulsory legislation can comprise as much as half of the floor agenda. Moreover, even within the discretionary agenda the majority may be compelled to act even when it is divided or incapable of taking legislative steps by itself. Majority parties may succumb to public pressure and act on issues on which they cannot unify behind a single position. It may be good politics to do so to try to avoid generating public discontent and electoral backlashes to inaction (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013; Weissberg Reference Weissberg1978) or as an attempt to expand the party’s coalition (Karol Reference Karol2009).

Examples are not hard to find. Consider the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act. In 2012, the GOP House majority refused to negotiate with Democrats over an expansion of the law. But after the 2012 elections, with Republicans wary of being accused of continuing a “war on women,” they allowed the Democrats’ version of the bill, which substantially expanded the scope of the law, to come to the House floor where it passed with unanimous support from the minority Democrats, and only limited support (39%) from the majority Republicans.Footnote 8

Congressional majority parties may also pursue legislation in the absence of internal party unity because of promises made on the campaign trail. The Republicans, for example, ran several national campaigns between 2010 and 2016 promising to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA). When the party took unified control of the government in 2017, they moved forward to repeal (and replace) the ACA despite clear disagreements within the party. According to Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), Republicans did so because the effort was about “keeping our promise.”Footnote 9 Democrats have also pushed for legislation without internal unity because of campaign promises. Various climate change bills proposed in recent years fit this description. Even in the 111th Congress (2009–10), with large majorities in both chambers, Democrats were unable to unify behind a cap-and-trade bill in the House, needing Republican votes to ensure passage. In the Senate, Democratic disunity resulted in failure.Footnote 10

The point is that majority parties sometimes face greater or fewer constraints as they attempt to legislate and are often in need of minority party votes to advance legislation, even in the House.Footnote 11 Greater constraints on the majority present greater opportunities for the minority party, and potential capacity for legislative influence.

Cohesion

Second, the minority party also needs to be cohesive enough to take advantage of its opportunities for influence. In other words, it needs to be able to hold together enough of its votes to meaningfully shape policy outcomes and win substantial concessions from the majority. In the absence of sufficient cohesion, the majority may be able to pick apart the minority, siphoning off just enough votes to do what it wants and make limited concessions.

Examples are again instructive. In 2009, congressional Democrats were twice able to take advantage of disunity among minority Republicans to get the bare minimum number of votes they needed. In the first case, fully unified behind advancing their economic stimulus package (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act), Senate Democrats negotiated with three moderate Republicans—Susan Collins (R-ME), Olympia Snowe (R-ME), and Arlen Specter (R-PA)—giving them just enough votes to secure cloture.Footnote 12 Unable to hold their members together, the minority Republicans could neither block nor push for broader changes to the Democrats’ plan. Later that year, minority Republicans saw their capacity limited once again, even though the majority was constrained by its own disunity. Democrats pushed their cap-and-trade bill (the American Clean Energy and Security Act) over the finish line in the House—even as 40 Democrats opposed it—by winning the support of just enough Republicans (8 in total) to secure passage.Footnote 13 Had Republicans been able to hold their members in line, they could have either negotiated broader changes to bill or kept the Democrats from passing it at all.

Democrats have also failed to coalesce at times when in the minority, including during the Republicans’ successful effort on the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005. Short of the votes needed to pass their class-action lawsuit overhaul on their own, the majority Republicans were able to pick off about one-quarter of Democratic lawmakers in both chambers, making limited concessions along the way.Footnote 14 In this case, as in the others, the minority party had less capacity to influence the ultimate legislative outcomes because they were unable to hold together, even though there were clear constraints on the majority party.

In other cases, minority parties have had greater capacity for influence because of sufficient intraparty cohesion. Welfare reform in the 104th Congress (1995–96) is one such example. Repeatedly, Republicans pushed aggressive entitlement reform bills that never had the votes to overcome opposition from President Bill Clinton.Footnote 15 Only after substantially paring down the proposal to meet Democratic demands was success achieved.Footnote 16 Another example is Republican efforts to roll back parts of the Dodd-Frank financial services reforms during the 115th Congress (2017–18). Republicans initially sought a wide-ranging roll-back and pushed their plan through the House on a party line vote.Footnote 17 Without any Democratic support, however, the proposal was doomed in the Senate. The Democrats held together well enough to force Republicans to abandon their ambitious plans. The bill that passed was far more limited in scope and focused on more bipartisan proposals to revise Dodd-Frank.Footnote 18

Altogether, how cohesive the minority party is on a bill or issue is another important factor in minority party capacity. Minorities able to hold together against the majority party’s legislative efforts can block action or demand substantial concessions, especially when the majority is also more constrained.

Motivation

Finally, if the majority party is constrained and the minority party is cohesive, the minority still needs to be motivated to engage in legislating rather than electioneering. In other words, minority parties make choices about how to approach different legislative battles (Green Reference Green2015; Koger and Lebo Reference Koger and Lebo2017; Lee Reference Lee2016). The minority party can either use the leverage they have to engage in legislating and influence legislative outcomes or they can forego those opportunities and focus on benefits gained through opposition or obstruction. The latter choice may produce short-term electoral benefits or long-term legislative benefits as the minority party waits for its situation in Congress to improve by winning future elections and gaining seats. But such a choice precludes any legislative influence the party could have at that moment.

Minority parties may be more or less motivated to engage in legislating on an issue for several reasons. They may feel more pressure to legislate, rather than obstruct, in emergency situations or against statutory deadlines that carry serious consequences for inaction. Economic disasters, foreign policy crises, global pandemics, and government shutdowns may, at least some of the time, spur minority parties to engage with their majority counterparts. Minority parties may also feel more pressure to legislate when action on an issue is popular with the public.

We might also expect a minority party’s motivation to be greater in response to presidential leadership during divided government. This is true for at least two reasons. First, minority parties generally feel more pressure to “govern” when they control at least some part of the government (Lee Reference Lee2016). When the other party has unified control, minority parties have the greatest incentive to focus their efforts in Congress on opposition, obstruction, and electioneering. In contrast, when a minority finds itself in control of at least one of those national institutions, such as when it controls the White House during divided government, its incentives shift. Under those conditions, the general performance of the government is likely to affect the party’s electoral fortunes, as they are tied to the standing and success of their president (Bafumi, Erikson, and Wlezien Reference Bafumi, Erikson and Wlezien2010; Erikson Reference Erikson1988; Jacobson Reference Jacobson2019). Consequently, minority parties may feel greater incentives to legislate, and enact some policies, to demonstrate effective governance (Green Reference Green2015).

Second, when the minority party controls the White House under divided government, minority party lawmakers will feel more pressure to legislate in support of presidential policy priorities and initiatives. Presidents enter office with policy agendas and they work to build support in Congress to enact them (Mayhew Reference Mayhew2011). Members of Congress typically feel pressure to support a president’s agenda when they are of the same party, sometimes even supporting proposals and positions that members might otherwise oppose (Lee Reference Lee2009). Consequently, on bills and issues of great importance to the president, his or her copartisans in Congress may be particularly motivated to legislate rather than electioneer.

Of course, minority parties are not only motivated by presidential leadership. Congressional parties have their own agendas (Curry and Lee Reference Curry and Lee2020), and minority parties during periods of unified government also sometimes have sufficient capacity and use it to influence legislative outcomes. These motivations may stem from the priorities of minority party congressional leaders or from demands of a party’s voters and allied groups. Regardless of from where minority party motivations stem, the desire to legislate, rather than electioneer, is the final factor in determining the minority party’s legislative capacity.

Assessing Minority Party Capacity

Our theory of minority party capacity should predict minority party influence over a number of legislative outcomes. We test our theory in three ways. First, we assess the influence of minority party capacity on the content of the floor agenda in the House of Representatives. We focus first on House agenda setting because it presents an especially difficult test. The House floor agenda is expected to be controlled almost exclusively by the majority party because it has nearly monopolistic control over institutions governing procedures in that chamber (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). If we can find evidence of minority party influence within this process it is likely to exist elsewhere, too. Second, we look for downstream effects on legislative outcomes by assessing how well our theory predicts which bills become laws. Third, we present three case examples demonstrating the role of minority party capacity in shaping the substance of policies enacted on Capitol Hill.

These three sets of analyses not only allow us to assess how majority party constraints, minority party cohesion, and minority party motivation explain minority party influence across different legislative outcomes but also provide insight into outcomes not well understood through the lens of scholarship on majority party power. Generally, theories of majority party power expect majorities to take control of the congressional agenda, block legislation that divides the majority (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005), and enact legislation reflecting majority party preferences (Aldrich and Rohde Reference Aldrich, Rohde, Bond and Fleisher2000). Here, we analyze and attempt to explain relatively common, but understudied, cases in which minority parties exercised more influence than majority party focused theories expect.

Analysis Overview

For the quantitative analyses, we used as data every bill and joint resolution (hereafter: bills) introduced in the House of Representatives from 1985 to 2006 (99th–109th congresses). We excluded bills not substantive in nature, such as those naming buildings or transferring small plots of land between government entities, using the Congressional Bills Project’s data (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2018).Footnote 19

We use two dependent variables for our quantitative analyses. For our agenda-setting analyses, the dependent variable is whether or not each bill received a final passage vote on the floor (regardless of whether it passed or failed).Footnote 20 Since nearly every bill considered on the floor receives a passage vote, this variable allows us to easily capture what does and does not make it onto the floor agenda. For our analyses predicting which bills became law, the outcome variable is simply a dichotomous measure of whether or not each bill became a public law. In our lawmaking analyses, we separately model all bills and the subset of bills that had already passed the House.

For the case examples, we draw primarily upon in-depth coverage of policy-making efforts in CQ Magazine. CQ Magazine (formerly CQ Weekly) is a weekly periodical that provides coverage of every major law enacted on Capitol Hill in real-time, and it is read regularly by government officials, lobbyists, and the media. With its frequent coverage of major lawmaking efforts, it is easy to track what unfolded on an issue or set of issues across a congress.

For both the case examples and the quantitative analyses, we draw on three primary independent variables for our analyses, each reflecting one of the three aspects of minority party capacity described above: majority party constraints, minority party cohesion, and motivation. In the quantitative analyses, these measures were the primary explanatory variables in regression models. For the case examples, these variables helped us to identify cases and provided a lens for understanding the minority party’s influence in each case.

Constraint and Cohesion

Two of the factors in our theory of minority party capacity are constraints on the majority party and minority party cohesion. As described above, these factors are primarily affected by the level of disunity within the majority party (constraint) and unity within the minority party (cohesion) on the proposal being considered. As such, we developed issue-specific measures of intraparty disunity, or heterogeneity, for both majority and minority parties in the House of Representatives over the period of our study. Previous scholarship demonstrates that party cohesion and party differences vary from issue to issue, even in recent, party-polarized congresses (see Crespin and Rohde Reference Crespin and Rohde2010; Jochim and Jones Reference Jochim and Jones2013). We build on these findings to construct our measures.

We first created new issue-specific “preference” measures for each member of Congress via W-NOMINATE. We estimated separate W-NOMINATE scores for different policy areas for each member using the votes on bills falling into each of the Comparative Agendas Project’s 20 major issue topics from the 99th to 109th congresses (1985–2006).Footnote 21 Our choices of this period and of W-NOMINATE (instead of DW-NOMINATE) were systematic. Any vote-scaling procedure requires that there be enough votes for convergence. There are, on average, a few hundred roll-call votes across all of the topic designations in each congress, meaning that very few issues receive enough votes within a single congress to get stable estimates (Crespin and Rohde Reference Crespin and Rohde2010). Thus, we chose to analyze periods that were as lengthy as possible. Further, because our theory concerns dynamics between the majority and minority parties—rather than between the Democratic and Republican parties—we must also choose periods of stable majority control by a single party and scale the votes separately within each period. In our sample of congresses, Democrats controlled the House continuously from 1985 to 1994 (99th–103rd congresses) and Republicans controlled the House continuously from 1995 to 2006 (104th–109th congresses).

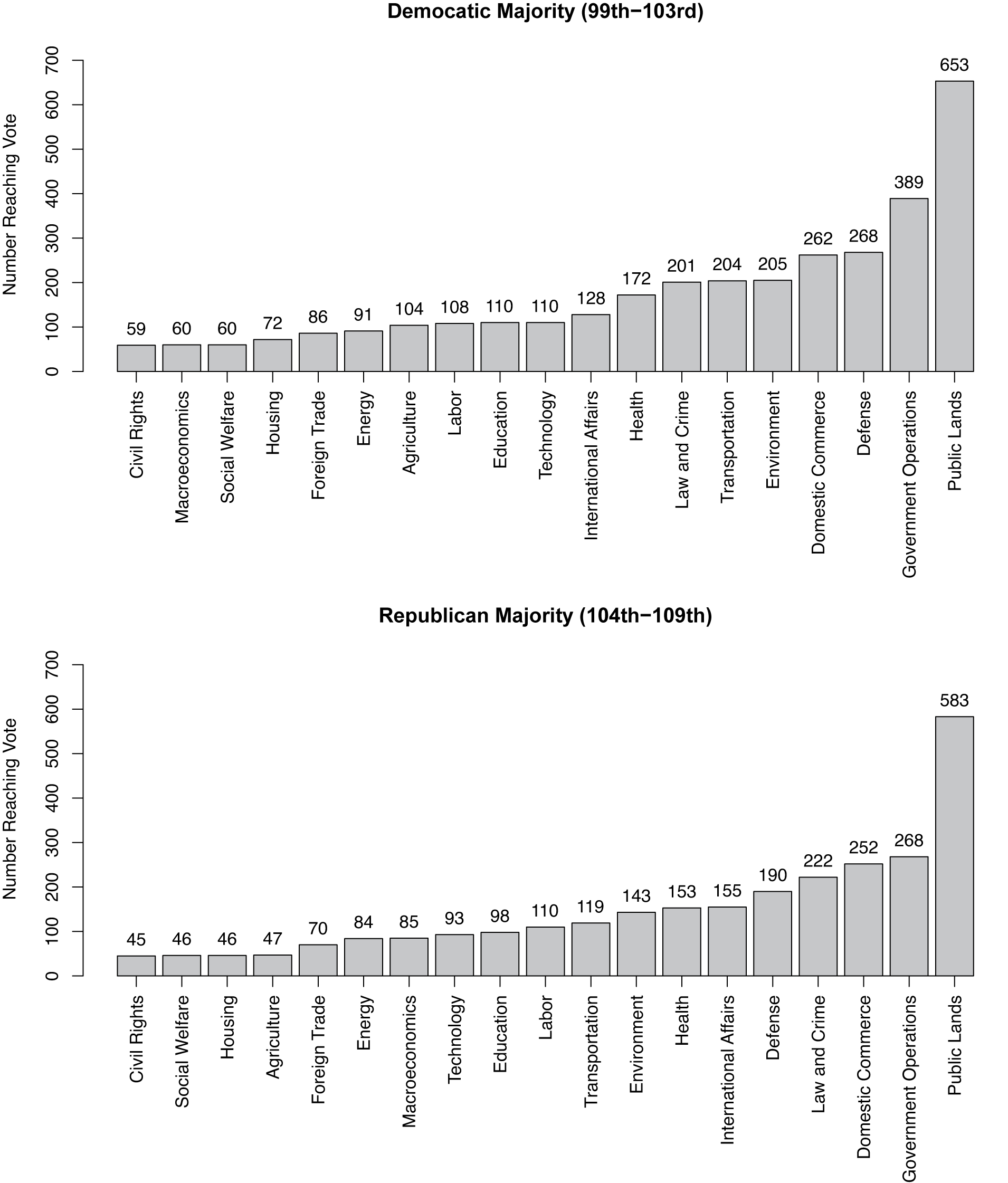

The number of bills in each issue area receiving a final passage vote in the House are displayed in Figure 1 for each period. While for many issues there were only a few dozen votes, this is enough to get stable issue-specific measures. We end our analysis after the 109th Congress (in 2006) because since then neither party has controlled the House for a long enough continuous period to have enough votes in enough issue areas for adequate estimates. Though Democrats continuously controlled the House for many years before the 99th Congress, we do not have access to other important variables before the 99th Congress to conduct our analyses.

Figure 1. The Number of Bills Reaching a Vote From Each Issue in Each Period Studied

We chose W-NOMINATE over DW-NOMINATE because the number of votes required for convergence is lower for W-NOMINATE. DW-NOMINATE estimates a separate score for each legislator during each Congress, whereas W-NOMINATE estimates a single score for members across a period. This means that our estimate for each member on each issue will be static for the 99th–103rd congresses and again for the 104th–109th congresses. However, as members’ DW-NOMINATE scores are relatively stable over time (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2000; Poole Reference Poole2007), this should be of little concern.

Armed with these issue-specific measures for each member, we were able to compute measures of intraparty differences, or heterogeneity, for the majority and minority parties during each period. The first of these, majority spread, is the standard deviation of preferences within the majority party on each issue during each period. Larger values indicate more heterogeneity within the majority, or in other words less unity, and thus reflect a more constrained majority party on that issue.Footnote 22 The second measure is minority spread, measured as the standard deviation of preferences within the minority party on each issue topic during each period. As with the first measure, smaller values indicate less heterogeneity, or more unity, and thus reflect a more cohesive minority party on that issue.Footnote 23

Our theory of minority party capacity expects that the minority party will have greater capacity for influence when majority spread is higher and minority spread is lower. Further, as the examples we gave in the previous section show, we expect to see the interaction of these factors predict which bills are considered on the floor and become law in our analysis.

These NOMINATE-based variables are far from perfect. NOMINATE, after all, cannot intuit why members of Congress cast the votes that they do, including whether those votes reflect true preferences on an issue or strategic voting (Herron and Shotts Reference Herron and Shotts2003; Stiglitz and Weingast Reference Stiglitz and Weingast2010) or party pressure (Curry Reference Curry2015; Evans Reference Evans2018; Lee Reference Lee2009). NOMINATE-based measures are also imprecise in some well-known ways, including in the estimation of ideal points for members who vote against most of their own party because they view the party’s position as too moderate (Duck-Mayr, Garnett, and Montgomery Reference Duck-Mayr, Garnett and Montgomery2020). Moreover, within any issue area, members of Congress take votes on very different bills that propose to move public policy in very different directions.Footnote 24 Different bills, and different issues, are also subject to different political forces, including the amount of pressure party leaders put on their members to vote one way or the other.

Nevertheless, our measures of issue-specific intraparty spread should prove adequate for our purposes. NOMINATE is imperfect, but it is highly correlated with other measures of members’ preferences including those based on campaign contributions (Bonica Reference Bonica2013), cosponsorship patterns (GovTrack 2020), and floor speeches (Rheault and Cochrane Reference Rheault and Cochrane2020).Footnote 25 In part, this suggests that while NOMINATE is at times imprecise, there is little evidence of widespread bias, particularly at the aggregate level of party distributions. Since our intent is to construct measures that generally capture the relative amount of unity or disunity each party demonstrates across political issues, the reasons for that expressed (dis)unity—such as pressure from party leadership or other forces applied to specific members—are less of an issue. The biggest limitation of these measures is that, given imprecision in W-NOMINATE, they are noisy. This should, if anything, make it more difficult for our analyses to produce significant findings, making them conservative tests of our theory.

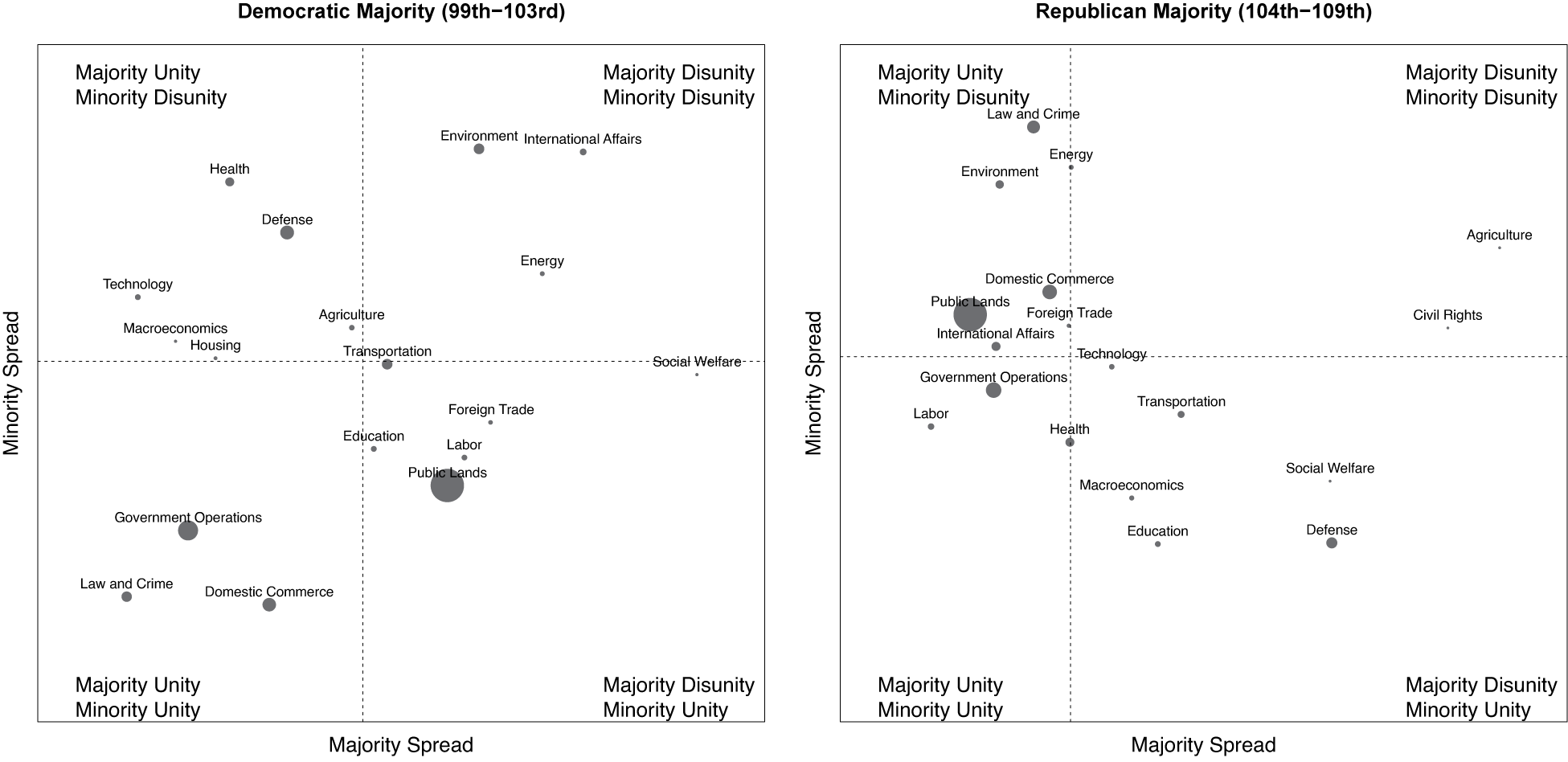

Our measures of majority and minority spread in each period are shown in Figure 2. The figure shows which issue areas fit different combinations of high and low majority and minority party spread in both periods we study. As shown, there is substantial diversity across issues and differences between periods. While bills addressing labor, public lands, and foreign trade are those that presented substantial majority party disunity (constraints) alongside high levels of minority party cohesion during the period of Democratic majorities (99th–103rd congresses), these issues are found in other quadrants during the period of Republican House majorities (104th–109th congresses). In contrast, during Republican majorities, issues such as defense, education, social welfare, and transportation present this dynamic.

Figure 2. Party Spread in the Majority and Minority Party on Each Issue in Each Period Studied

Note: Horizontal and vertical dashed lines are the median spread across all issues in the minority and majority parties in each period, respectively. Dot size indicates the relative number of bills within each topic.

Motivation

The third factor in our theory of minority party capacity is the minority party’s motivation to legislate rather than electioneer. Motivation is the most difficult aspect of our theory to measure. Consistent with our theory, we focus on presidential leadership, and expect to find that the minority party is particularly motivated to legislate on issues that are priorities to the president during congresses when the House minority party controls the White House.Footnote 26

To measure the president’s issue priorities, we used the Policy Agendas Project’s data on State of the Union addresses. These data code every quasi-statement made in each State of the Union address for its issue content. For our purposes, we coded each bill as addressing a presidential priority issue if its issue subtopic (one of 220) received a mention in either State of the Union address given during a Congress. The resulting measure, Minority priority, is a simple dichotomous variable. Rather than interact this variable with an indicator for divided government, we limit our analysis of this variable to years in which the House and the White House were controlled by different parties. In these analyses, we expect to find that bills addressing presidential priority issues are more likely to be considered on the floor, especially when the minority has greater opportunity, and higher cohesion, on those same issues.Footnote 27

Control Variables

We included several control variables in our quantitative analyses that may affect the fate of bills. One set of variables captures the partisan dynamics of each Congress. These include a measure of party conflict on each issue, party difference, measured as the difference between the median of the distribution of preferences in each party on each issue during each period. Just as disagreements within the parties may shape efforts at legislating, so may disagreements between them. Several other variables capture the dynamics of partisan control of government in each Congress. House majority size measures the number of seats the majority party would have to lose before becoming the minority party, seats in Senate measures the number of seats the majority party in the House holds in the Senate, and White House control is an indicator of whether or not the House majority party also controls the White House. We also controlled for overall majority party unity, measured as the House majority party’s average party unity score during each congress.Footnote 28

We also included several bill-level controls. Majority priority is a measure of whether or not a bill addresses a majority party issue during each Congress.Footnote 29 Closer to minority uses cosponsorship data to assess the dynamics of support for each bill. Specifically, this is a dichotomous indicator of whether the median DW-NOMINATE score of a bill’s cosponsors is closer to the minority party median than the majority party median. We also include a dummy variable indicating whether a House bill has a related bill introduced in the Senate (related in Senate). If both chambers are working on a similar policy at the same time, there is a higher likelihood of success for the bill.Footnote 30 Finally, we include a dummy variable indicating whether a measure was introduced during an election year, as parties may have differential effects on the floor agenda in the first and second years of a Congress.

We also included controls about each bill’s sponsor that might predict the likelihood of floor consideration or passage. These include: whether the member was in the majority party, the member’s electoral safety (the absolute value of the Partisan Voter Index score in the member’s district), whether that member was in the party leadership,Footnote 31 each sponsor’s legislative effectiveness score (Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2018), and whether the sponsor has a seat on a committee the bill was referred to after introduction (member referral committee).

Results of the Quantitative Analyses

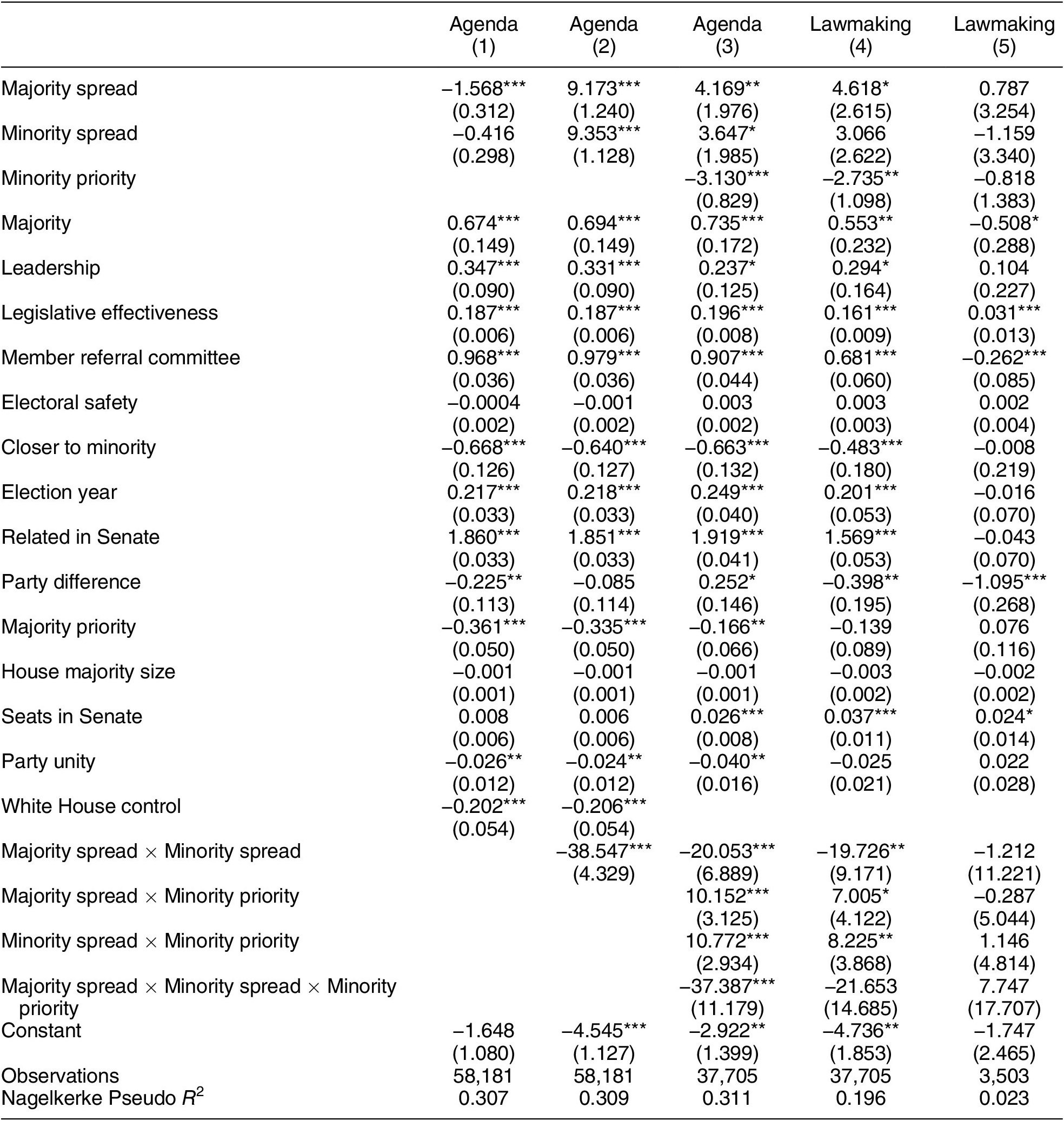

In this section we present the results of our quantitative analyses. We first present the results of our agenda-setting analyses, then the results of the lawmaking analyses. The results of logistic regression models predicting which bills received a final passage vote and which became law are shown in Table 1. Both sets of analyses demonstrate the explanatory value of our theory.

Table 1. Logistic Regression Models Predicting Whether a Bill Receives a Final Passage House Vote (Columns 1–3) or Becomes Law (Columns 4 and 5)

Note: Standard errors in parentheses; *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Agenda Setting

Results of models assessing our theory of minority party capacity in predicting whether bills reach a final passage vote in the House are in columns 1–3 of Table 1. Column 1 shows the independent effects of our measures of majority party constraints and minority party cohesion (majority spread and minority spread, respectively) on the likelihood that each bill received a vote on the floor. In column 2, we added an interaction between the two spread measures, assessing the interactive effects of majority party constraints and minority party cohesion. In column 3, we added our measure of minority party motivation (minority priority) and include a three-way interaction among all three variables. As a result, the third column only includes years of divided government.

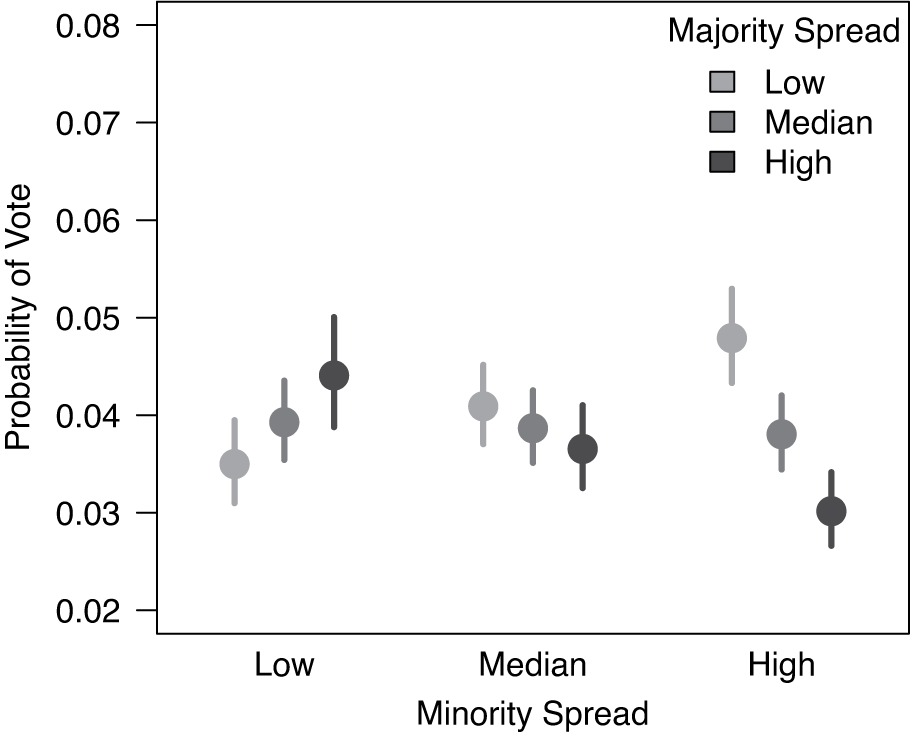

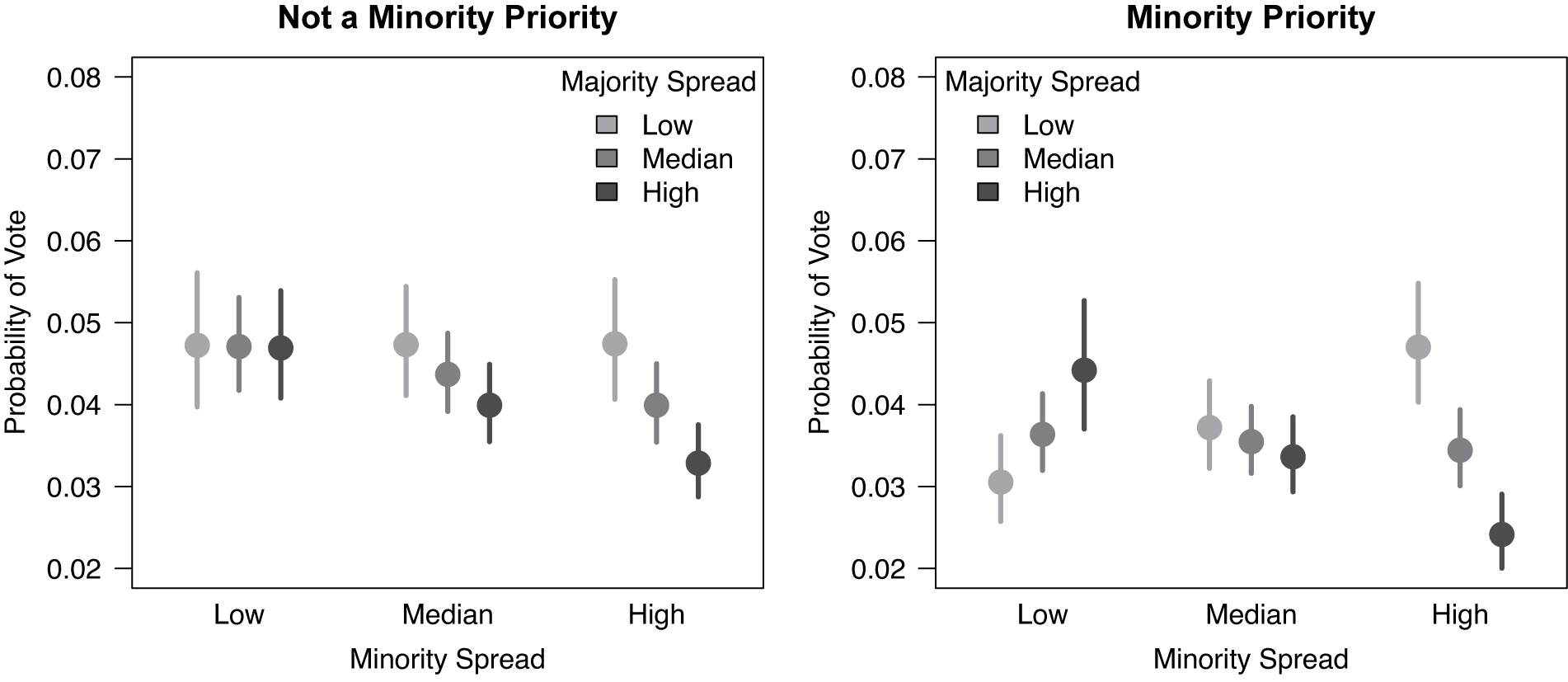

The results in column 1 show that both spread variables have negative coefficients, suggesting that bills were less likely to reach the floor as both majority spread and minority spread increased. However, central to our theory is that these factors work in tandem to provide minority parties with greater capacity for influence. We model these dynamics with two- and three-way interactions between our main independent variables in columns 2 and 3, respectively. The results in column 2 include an interaction term between the spread variables. The interaction coefficient is negative and statistically significant. But as interaction effects can be difficult to interpret directly from regression tables, the predicted effects of this interaction presented in Figure 3 provide more insight.

Figure 3. Predicted Probability That Bills Reached a Final Passage Vote as a Function of the Interaction between Majority Spread and Minority Spread

Note: High and low values are one standard deviation above and below the median value of spread in each party. The lines are 95% uncertainty estimates.

Figure 3 shows the probability a bill received a floor vote under different combinations of majority spread and minority spread. For each variable, “high” and “low” spread values are one standard deviation above or below that party’s median, respectively. For the majority party, higher spread indicates it was more constrained on an issue. For the minority party, lower spread indicates it was more cohesive on an issue. Figure 3 shows there are two combinations of majority and minority spread under which bills had the highest likelihoods of receiving a floor vote. The first is one we would expect from theories of majority party power: when the majority had low spread (was relatively unconstrained) and the minority had high spread (was less cohesive). Under these conditions, a bill had a 5% probability of receiving a floor vote. The other condition, however, reflects the logic of our theory of minority party capacity: When the majority had high spread (was relative constrained) and the minority had low spread (was cohesive), bills also had a 5% probability of floor consideration, a likelihood higher than all of the other combinations of majority and minority spread. This finding deserves reiteration. House bills addressing issues that unified the minority and divided the majority were just as likely to be considered on the House floor as those that unified the majority and divided the minority. There is no meaningful difference. This is strong evidence for the constraint and cohesion aspects of our theory.

Column 3 of Table 1 includes a three-way interaction that allows us to also assess the effect of minority party motivation on the probability that bills received a floor vote. The three-way interaction between the spread variables and minority priority is statistically significant, but again, plotting predicted values is helpful to assess the substantive effects. We present the effects of this three-way interaction in Figure 4, which mirrors Figure 3 in that it shows the predicted likelihood bills received a floor vote under different combinations of majority and minority spread, but it also splits the analyses by whether a bill addressed a minority priority issue (right) or not (left). Recall, because we measure minority priorities as issues mentioned by presidents during years when the House and the White House were controlled by different parties, these results only include this subset of years (7 of the 11 congresses in our data).

Figure 4. Predicted Probability That Bills Reached a Final Passage Vote as a Function of the Interaction among Majority Spread, Minority Spread, and Minority Priority

Note: High and low values are one standard deviation above and below the median value of spread in each party. The lines are 95% uncertainty estimates.

Figure 4 provides strong support for our theory. Whereas we find no clear effect of the interaction of the spread variables among bills that were not minority priorities, we find results that mirror those in Figure 3 among bills that were minority priorities. Among these, bills addressing issues that had low minority spread and high majority spread once again had among the highest likelihoods of reaching the floor, similar to those that unified the majority and split the minority. Similar to the results in Figure 3, bills under these two sets of conditions had chances of coming to the floor that were statistically indistinguishable.

Our agenda analyses provide strong and consistent support for our theory. In the appendix, we present the results of analyses using only bills introduced by members of the minority party. The results are similar to those presented here, and if anything, show stronger effects among our measures of minority party capacity. Combined, these results demonstrate that our theory of minority party capacity helps predict the contents of the House floor agenda, a process that has typically been understood to be driven by majority party concerns and dynamics.Footnote 32

Lawmaking Outcomes

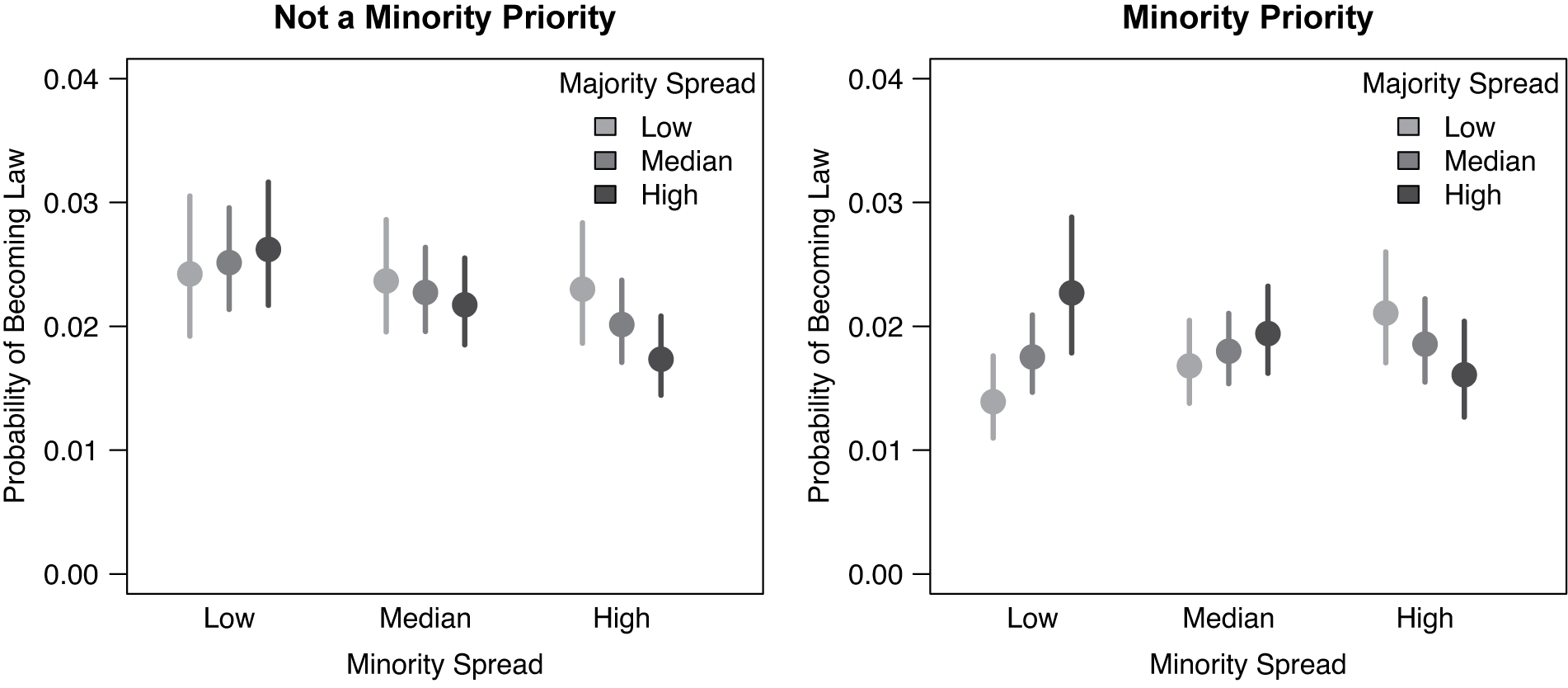

Next, we assess the effects of minority party capacity on which bills become law. The results of these models are presented in columns 4 and 5 of Table 1. Column 4 contains results for all bills, and column 5 contains results for the subset of bills that had already passed the House. Both models only include bills considered under divided government so that we can assess all three aspects of our theory: constraint, cohesion, and motivation. As before, we use predicted effects plots to tease out the effects of the interactions among our key variables.

Figure 5 shows the predicted probability of whether any bill became law (column 4 of Table 1). As in Figure 4, Figure 5 shows predicted likelihoods at different combinations of majority and minority spread for bills that were and were not minority party priorities. The pattern observed in the previous figures, which supports our theory, is readily apparent once again. If anything, the effect of the interaction term on the probability that bills became law is even stronger than when predicting which bills reached the floor. Minority priority bills with high majority spread (a constrained majority) and low minority spread (a cohesive minority) had the highest predicted probabilities of becoming law. Indeed, when the minority is cohesive (low spread), bills were twice as likely to become law when majority spread was high than when majority spread was low (2% versus 1%). Given that the probability of any bill becoming law is very low, this difference is quite substantial.

Figure 5. Predicted Probability That Bills Became Law as a Function of the Interaction among Majority Spread, Minority Spread, and Minority Priority

Note: High and low values are one standard deviation above and below the median value of spread in each party. The lines are 95% uncertainty estimates.

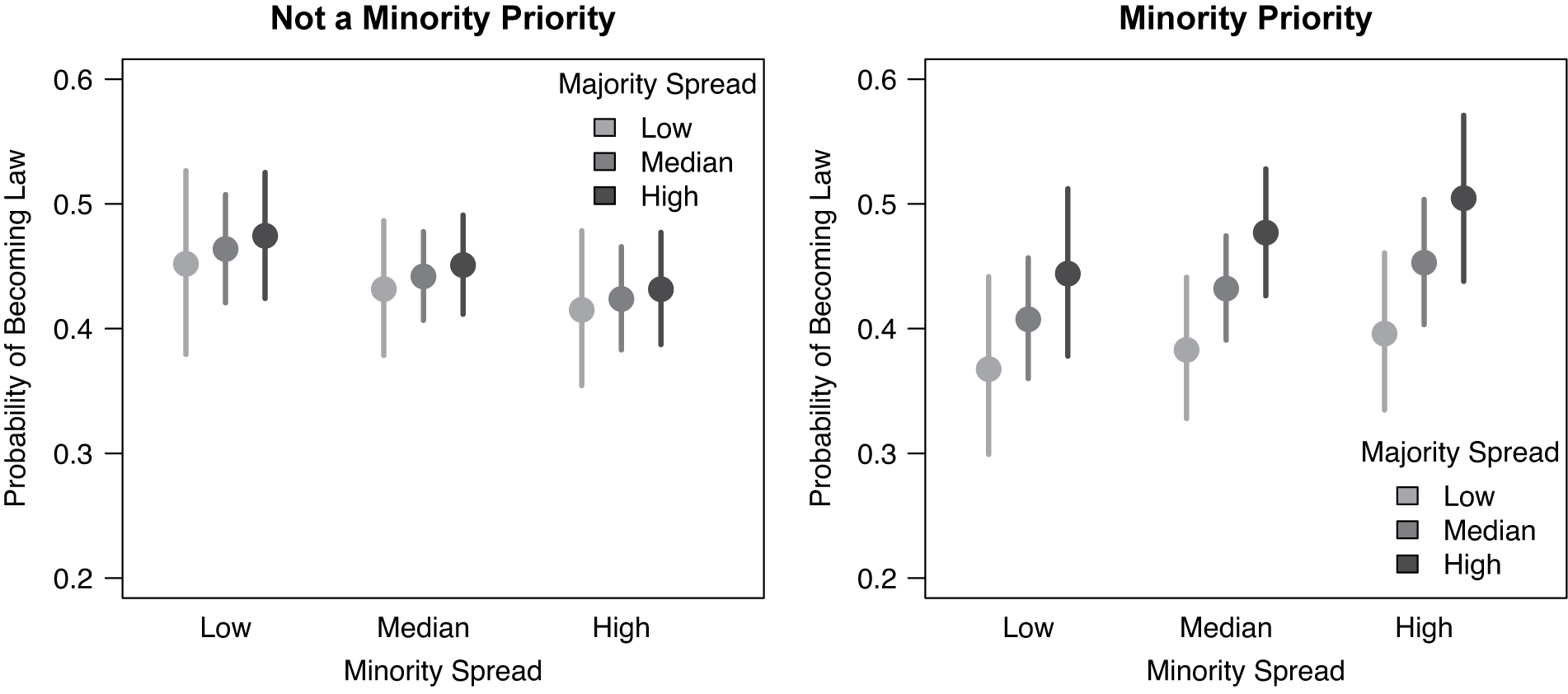

Figure 6 follows the same format as do Figures 4 and 5 but contains predicted probabilities that bills became laws for the subset of bills that already passed the House. In this case, the result do not fit quite as neatly with our theory, but we still find partial support. While minority party cohesion does not appear to have much of an influence on the likelihood that bills become law after passing the House, both majority party constraint and minority party motivation affected the probability that bills became law. Among bills that passed the House, those addressing issues that divided the majority were more likely to become law than those that unified it, but only for bills dealing with issues that were priorities for the minority party. Regardless of the level of minority party cohesion, those bills were nearly twice as likely to become law. This is a substantial difference in probability that provides additional support for our theory.

Figure 6. Predicted Probability That Bills Became Law as a Function of the Interaction among Majority Spread, Minority Spread, and Minority Priority for Bills That Passed the House

Note: High and low values are one standard deviation above and below the median value of spread in each party. The lines are 95% uncertainty estimates.

Minority Party Capacity and Policy-making Outcomes

The quantitative results demonstrate the utility of our theory for predicting outcomes: which bills are considered on the House floor and which become law. In this section, we present three case examples that illustrate the utility of our theory for explaining minority party influence over the substance of public policy outcomes. Each case was selected from issue areas in the bottom-right quadrant of the two panels in Figure 2, or in other words, when the majority was relatively constrained and the minority was relatively cohesive. Each is also a case for which the minority party had clear motivation to engage in the legislative process. Two of the cases took place during unified government and one during divided government. In each case, the minority party had levels of influence that would not be expected from theories focused on majority party power.

K-12 Education Policy (106th Congress)

First, consider Congress’s efforts to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act during the 106th Congress (1999–2000). With the law set to expire in 2000, the majority leadership declared, “Education is No. 1 on the agenda of Republicans.”Footnote 33 Republican leaders had several ambitious reforms in mind, including transitioning some federal funds to block grants, giving states more flexibility to use federal education dollars, expanding education savings accounts, and establishing more permissive school choice policies. However, a number of these ideas divided congressional Republicans. Proposals to give states more flexibility to work around federal education requirements, for example, were opposed by moderate Republicans,Footnote 34 and this opposition ultimately sank the education savings account bill (H.R. 7).Footnote 35

The minority Democrats, on the other hand, found themselves far more unified on an issue that had long been a party priority. President Clinton had often placed education policy front and center during his two terms in office, including in his 1999 State of the Union address where he called for increased federal spending to hire 100,000 new teachers and refurbish run-down public schools, while holding school districts more accountable to rigorous federal standards. Throughout the two-year legislative battle over education policy, House Democrats proved to be unified in opposition to the Republicans’ reform proposals. They held firm against the majority’s most ambitious plans, fully opposing their education savings account bill (H.R. 7) and holding at least 90% of their caucus together against Republican plans to block-grant education spending (H.R. 1995) and to make it easier for states to receive waivers from federal requirements (H.R. 2300).

In the end, a divided Republican majority struggled to pass its agenda while a unified Democratic party, with a motivated and engaged president, worked its will. Republicans eventually passed 6 of their 7 reform bills through the House, but two were noncontroversial (passed by voice votes) and two more needed Democratic votes to pass. One of these was the Student Results Act (H.R. 2), which boosted Title 1 education funds and had more support from Democrats (200 votes in favor) than Republicans (157 votes).Footnote 36 In the Senate, only those bills with the broadest support among Democrats made any headway.

Republican attempts to reduce education spending also failed. In 1999, Clinton vetoed Republican-led efforts to make deep cuts to several education programs.Footnote 37 In 2000, Democrats and the White House held together to secure $10 billion more than the administration had asked for in its budget blueprint.Footnote 38 This final blow, enacted as part of a consolidated appropriations package (H.R. 4577), passed the House with more support among the minority Democrats (95%) than among majority Republicans (72%).Footnote 39

NAFTA Implementation (103rd Congress)

Second, consider the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Implementation Act in 1993. The 1992 elections saw Democrats gain unified control of the federal government, and Republicans completely out of power, for the first time in 12 years. Nevertheless, on NAFTA, Republicans obtained much of what they sought while providing most of the votes to enact the law.

Outgoing President George H. W. Bush completed work on a NAFTA agreement in late 1992, leaving it to his successor to push the deal through Congress. President Clinton took office in favor of ratifying the deal but faced stiff opposition from much of his own party, including two thirds of the Democratic leadership in the House.Footnote 40 Clinton worked diligently throughout 1993 to placate his party by negotiating side deals with Canada and Mexico around labor and environmental interests, but the Democrats nevertheless remained deeply divided over NAFTA.Footnote 41 By September, the Clinton team was well short of the 100 House Democratic votes it believed it needed to pass the bill.Footnote 42

Enter the GOP. The Republicans were far more unified behind NAFTA, though disagreements certainly existed. Nevertheless, their motivation to achieve a long-term goal in lowering trade barriers created a willingness among most Republicans, and the party’s leadership, to support the bill’s passage.Footnote 43 With help from the Clinton White House, Republican leaders aggressively whipped their members to support the bill on the floor.Footnote 44 Republicans also took advantage of the President’s eagerness to secure passage, winning a few (though minor) concessions on taxes in the plan.Footnote 45

In the end, House Democratic leaders put the NAFTA bill on the floor where it passed over the objections of 156 Democrats (60% of the caucus) but with the support of 75% of House Republicans. In the Senate, the bill was again supported by less than half of the Democrats, but 77% of Republicans. The final deal preserved most of what President Bush had negotiated. The changes made to placate labor and environmental interests underwhelmed most congressional Democrats and failed to secure their support.

Motivated to see a trade deal enacted and unified enough to provide a substantial number of votes, Republicans were able to take advantage of Democratic disunity, and the energy of President Clinton, to see their goal achieved. All this was achieved despite unified Democratic party control of government. This is not a scenario under which most scholarship would expect to find significant minority party influence. However, our theory of minority party capacity provides useful insight.

Voting Rights (109th Congress)

Finally, consider the effort to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act during the 109th Congress (2005–06). Fresh off an election victory in 2004 that saw George W. Bush return to the White House and Republicans gain seats in both the House and Senate, the GOP leadership made reauthorizing the Act a priority for the coming Congress. Though it would not expire until 2007, Speaker Hastert (R-IL) set aside H.R. 9 for the eventual bill, and Republicans held a bicameral public unveiling on the steps of the Capitol to publicize their effort. Republicans wanted to “use the upcoming reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act to prove that Democrats don’t own the issue.”Footnote 46 Despite a hopeful start, the effort quickly ran into trouble because of division among Republicans. Southern Republicans wanted to eliminate the federal “pre-clearance” requirements for most southern states to alter their elections procedures. Other Republicans wanted to eliminate bilingual ballot requirements.Footnote 47 While the bill was reported by House Judiciary Committee with just one opposing vote, a number of contentious amendments that split committee Republicans signaled trouble brewing for the House floor.Footnote 48

The Democrats, on the other hand, were fully unified behind the bipartisan reauthorization bills drafted by the Judiciary committees. Republican leaders, wanting to quickly reauthorize the law, met the Democrats at their preferred point: a long-term reauthorization that made few, if any, changes to the law. Democratic Party identity had for decades been connected to support for voting rights. House Judiciary Committee chairman James Sensenbrenner (R-WI) had long been a champion of robust civil rights and voting rights legislation in his party and found himself in agreement with the Democrats about which way to go.Footnote 49 For Democrats, unity within the party gave them the leverage and the votes necessary to block changes to the law that had support from a majority of Republicans.

Democratic unity was crucial for passage in the face of divisions among Republicans. Trying to stave off defections within their ranks, Republican leaders pulled the bill in June 2006 amid contentious arguments within the party about its substance. But Democratic leaders signaled that any change to the bill as drafted would force their caucus to oppose it.Footnote 50 In the end, Republican leaders relented to the Democrats, putting the bill on the floor without changes. Allowing dissatisfied Republicans to offer numerous floor amendments, a majority of the GOP repeatedly failed to pass amendments that included changes to pre-clearance requirements, eliminating bilingual ballots, and moving up the law’s sunset provisions.Footnote 51

In the end, a 25-year extension of the Voting Rights Act sailed through both chambers and was signed by President Bush. While perhaps providing a symbolic victory for Republican leaders who wanted to frame their party in a more favorable light on voting rights, this was a substantive rout for the Democrats. The minority party got what it wanted on a core issue while a majority of Republicans found themselves dissatisfied. The minority was unified behind the bill, motivated to see it through, and presented with a deeply divided majority, which provided minority Democrats the capacity to shape public policy.

Conclusions

In this article, we improve scholarly understanding of when, why, and how minority parties have the capacity to influence legislative outcomes in Congress. We argue that minority parties have capacity for such influence when the majority party is constrained and the minority party is both cohesive and motivated to engage in legislating rather than electioneering. We find support for our theory using novel measures of issue-specific intraparty cohesion for majority and minority parties between 1985 and 2006. Statistical analyses demonstrate that our measures of minority party capacity help predict which bills are considered as part of the House floor agenda and which bills ultimately become law. Three case examples demonstrate how our theory provides insight into how minority parties can exercise influence over the substance of policy-making outcomes, including cases where the majority party was rolled in the process.

These findings have several important implications for how we understand party power in Congress. First, we show that minority parties play a significant role in legislating, and not just because of the filibuster or presidential vetoes. These veto points certainly give minority parties some influence. However, we show how minority parties can have the capacity for influence even in their absence. The setting of the House floor agenda is not a process that is directly affected by the Senate filibuster or by what presidents will or will not veto. And yet, our measures of minority party capacity consistently predict the content of the House agenda. Further, our case examples show how minority party influence still takes place during periods of unified government and as a result of majority party disunity in the House. The filibuster did not feature prominently in any of our case examples, and presidential vetoes were only relevant in one case. Minority party influence is about more than just veto points.

Second, beyond showing that the minority party can play a significant role in legislating, our results establish that an understanding of minority party power is often necessary to fully comprehend what happens on Capitol Hill. Indeed, our theory of minority party capacity provides insight into legislative outcomes not readily explained by prominent theories of congressional parties, which overwhelmingly focus on the power of the majority party, especially in the House of Representatives. For instance, Cox and McCubbins’s (Reference Cox and McCubbins2005) procedural cartel theory expects that majority parties will block nearly all legislation that internally divides it. However, majorities sometimes advance legislation that divides the majority and unifies the minority in ways that cartel theory cannot explain. Our framework shows how the right combination of majority disunity and minority cohesion and motivation can explain these outcomes. Moreover, while Aldrich and Rohde’s (Reference Aldrich, Rohde, Bond and Fleisher2000) conditional party government focuses on majority party unity, our findings indicate that minority party unity also shapes legislative outcomes. Importantly, our findings do not invalidate those of the major studies of majority party power. Majority parties clearly exercise substantial influence throughout the legislative process. What our theory does is help explain the gaps that exist: outcomes that are not well explained by scholarship focused on majority parties and that reflect the interparty bargaining that often happens on Capitol Hill.

Altogether, our findings show that congressional legislating and policy making are far more dynamic with respect to the influence of the two parties than is typically appreciated. Majority parties obviously exercise substantial influence, but minority parties play more than a passive role, even in the institutionally majoritarian House. The constraints faced by majorities and the cohesion and motivation of minorities influence the issues on the agenda, what passes, and what is ultimately included, or not, in the substance of public laws. To get a more complete understanding of what happens in American policy making, we must take a closer look at the role and influence of minority parties.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000381.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data and code to replicate all of the tables and figures in this article and the online appendix can be found at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3DRQOB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Ruth Bloch Rubin, Mike Crespin, Charles Finocchiaro, Anthony Fowler, Tyler Hughes, Jeff Lewis, Dave Rohde, Josh Ryan, Adam Zelizer, the participants of the University of Oklahoma’s CAC Working Group, the participants of the University of Chicago’s American Politics Workshop, and participants in workshops on legislative effectiveness sponsored by CLALS at American University and CEL at Vanderbilt University and the University of Virginia for their helpful comments on previous versions of this paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.