Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

A series of significant developments in French politics has recently touched off speculation about the possibility that a major transformation of the structure and behavioral patterns of the system of political parties is taking place. The most salient developments from 1958 until 1967 can be briefly listed: (1) the unprecedented longevity of governmental coalitions throughout the entire span of life of the Fifth Republic (only one Government overthrown in eight years); (2) the near single-party majority attained by the Gaullist UNR in the November, 1962 elections; (3) the ability of five major non-Gaullist parties to coalesce their forces behind only two candidates opposing General de Gaulle in the December, 1965 presidential election, with the resulting necessity for a second ballot; (4) the subsequent merging of forces on the moderate left and the moderate right into combinations bent upon coordinated efforts in the March, 1967 legislative elections; (5) the successful construction of a Gaullist electoral alliance limiting the number of official Gaullist first-ballot candidates in each constituency to one; (6) the electoral agreements between the Communists and the moderate left Fédération permitting only one candidate of the left to remain in the race in any constituency on the second ballot; and (7) the tendency of voters to reward the united fronts of the outgoing Gaullist majority and the consistent leftist opposition and to penalize the relatively small and ambiguous center force, the Centre Démocrate.

1 The debate among French observers has centered around the possibility of a two-party system emerging. See Le bipartisme est-il possible en France? (Paris: Association Française de Science Politique, 1965). Opinion in this colloquium was weighted toward caution. However, momentarily in the wake of the March, 1967 legislative elections, writers foreseeing a two-party system were having their inning: Fabre-Luce, Alfred, “Giscard ou Mendès,” Le Monde (March 17, 1967), p. 7 Google Scholar; Duverger, Maurice, “Vers le Dualisme,” Le Monde (March 19–20, 1967), p. 9.Google Scholar It is an assumption of the present article that considerable simplification of the party system can take place without a two-party system necessarily resulting.

2 The Fédération des Gauches Démocrates et Socialistes (left-center) and the Centre Démocrate (right-center).

3 For an incisive account of the 1967 legislative elections see Goguel, François, “Les élections législatives de mars 1967, “Revue française de Science politique, 17 (June, 1967), 429–467.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 The figure “six” for the number of effective major parties in 1958 is rather arbitrary. The following are considered to rate that characterization: the Communists, the Socialists, the Radicals, the MRP, the Gaullist UNR, and the Independents. What is striking, however, is that there has been a clear reduction in the number of splinter parties that have to be taken into account. In 1958 there were an additional four or five parties that had to be reckoned with, locally at least. By 1967 only two could by any stretch of the imagination be considered significant: the Parti Socialist Unifié on the left and the Alliance Républicaine on the right. For 1958 see Williams, Philip M. and Harrison, Martin, “La Campagne pour la referendum et les élections legislatives,” in Association Française de Science Politique, L' Etablissement de la Cinquième République: Le Referendum de septembre et les élections de novembre 1958 (Paris: Armand Colin, 1960), pp. 21–59.Google Scholar

5 In the election campaign the five major parties were grouped as follows: majority—UNR and Républicains Indépendants; opposition—Communists and Fédération des Gauches; ambiguous—Centre Démocrate.

6 Although most of the seven parties identified as “major” for 1958 voiced their support for the policies of General de Gaulle, there was no identifiable majority coalition as there was in 1967.

7 The term “Legislature” refers to the span of service of a given set of National Assembly deputies from one election to the next, as the term “Congress” refers to a given two-year term of office of members of the U. S. House of Representatives.

8 In addition to the standard fountainhead essay, Guttman, Louis, “The Basis for Scalogram Analysis,” in Stouffer, Samuel A. et al., Measure ment and Prediction, Vol. IV of Studies in Social Psychology in World War II (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1966), pp. 60–90 Google Scholar, see MacRae, Duncan Jr., Dimensions of Congressional Voting (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1958)Google Scholar; and Price, H. Douglas, “Are Southern Democrats Different? An Application of Scale Analysis to Senate Voting Patterns,” in Polsby, Nelson W., Dentier, Robert A. and Smith, Paul A. (eds.), Politics and Social Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1963), pp. 740–756.Google Scholar

9 A useful listing of such studies may be found in Anderson, Lee F., Watts, Meredith W. Jr., and Wilcox, Allen R., Legislative Roll Call Analysis (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1966), pp. 120–121, footnote 14.Google Scholar

10 Ibid., p. 90.

11 At this level of generality we move away from the initial objectives for which Guttman scaling was devised and first applied to legislative bodies: attitude measurement. The scale has been viewed in earlier studies as a kind of yardstick measuring various degrees to which roll calls express certain underlying attitudes: e.g., Belknap, George M., “A Method for Analyzing Legislative Behavior,” Midwest Journal of Political Science, 2 (November, 1958), 377–402 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Wood, David M., “Issue Dimensions in a Multi-Party System: The French National Assembly and European Unification,” Midwest Journal of Political Science, 8 (August, 1964), 255–276.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Most students have recognized that the legislative vote is likely to involve a more complex choice situation than the response to a survey question (e.g., Anderson, Lee F., “Variability in the Unidimensionality of Legislative Voting,” Journal of Politics, 26 (August, 1964), 568–585)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and they have therefore paid considerable attention to the relationships that can be found between the positions of legislators on the scales and (1) the various groups, organized and categorical, to which legislators belong or (2) certain properties of the constituencies they represent: e.g., MacRae, Duncan Jr., “Roll Call Votes and Leadership,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 20 (Fall, 1956), 543–558 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Rieselbach, Leroy N., “The Demography of the Congressional Vote on Foreign Aid, 1938–1958,” this Review, 58 (September, 1964), 577–588 Google Scholar; Patterson, Samuel C., “Dimensions of Voting Behavior in a One-Party Legislature,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 26 (Summer, 1962), 185–200 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Anderson, Lee F., “Individuality in Voting in Congress: A Research Note,” Midwest Journal of Political Science, 8 (November, 1964), 425–429.CrossRefGoogle Scholar In attempting to characterize an entire legislative body in Guttman scaling terms, I hope, among other things, to make evident the possible applications of the tool in comparative study, whether cross-national or cross-state.

12 MacRae, Duncan Jr., “A Method for Identifying Issues and Factions from Legislative Votes,” this Review, 59 (1965), 909–926.Google Scholar

13 MacRae's findings fit this pattern for the Democrats in the House of Representatives, but the results for the Republicans are mixed: ibid., 922–923. See also Aydelotte, William O., “Voting Patterns in the British House of Commons in the 1840's,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 5 (January, 1963), 134–163 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; MacRae, Duncan Jr., “Intraparty Divisions and Cabinet Coalitions in the Fourth French Republic,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 5 (January, 1963), 164–211 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Waldman, Loren K., “Liberalism of Congressmen and the Presidential Vote in Their Districts,” Midwest Journal of Political Science, 11 (February, 1967), 73–85.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

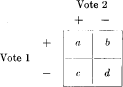

14 Two votes can be considered to share the property of unimensionality if they divide up the legislative body into only three of the four possible sub-sets shown in the following fourfold table:

So long as one of the four cells is unoccupied, unidimensionality prevails, although, if the unoccupied cell is either a or d, it will be necessary to reverse the signs of one of the items to make the items fit the conventional scale model: Anderson, Watts and Wilcox, op. cit., p. 92:

Here cell b is unoccupied and the deputies are divided by votes 1 and 2 into three sub-sets, with those in the center (c) having voted negatively on vote 1 and positively on vote 2. By extension, more than two votes would be perfectly scalable if each of the possible pairs among them exhibited pairwise perfection.

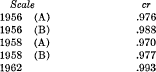

Clearly such perfection in human behavior is unattainable. Some measure of scalability must be used allowing a certain minimum of non-scalar behavior (i.e., a few deputies in the c cell in the above example). Before the pairwise method of scale-finding was introduced an overall measure of scalability, called the coefficient of reproducibility (cr), was used, permitting a certain % of “errors of reproducibility” (non-scale votes) scattered throughout the scale: see Guttman, op. cit., p. 77. With the pairwise method MacRae recommends the use of Yule's Q, a correlation coefficient designed for four-fold tables: “A Method for Identifying Issues and Factions from Legislative Votes,” op. cit. I am impressed by the necessity to measure correlation as well as reproducibility, but prefer a measure which combines the two standards, as φ/φ max rather neatly does. See Cureton, Edward E., “Note on φ/φ max,” Psychometrika, 24 (March, 1959), 89–91.CrossRefGoogle Scholar This measure provides for a comparison between cells b and c, which Q does not. The author is indebted to Mr. Joel S. Rose for demonstrating to him the applicability of the φ/φ max coefficient. By pegging φ/φ max at the .7 level it was found that no pair of items was admitted to a scale at less than the .94 level of cr for any of the scales of the three legislatures studied. The overall cr's for the five scales analyzed are presented in footnote 36, infra.

15 See Stein Rokkan, “Norway: Numerical Democracy and Corporate Pluralism,” and Stjernquist, Nils, “Sweden: Stability or Deadlock,” in Dahl, Robert A. (ed.), Political Oppositions in Western Democracies (New Haven: Yale university Press, 1966), pp. 70–146.Google Scholar When compared to the British two-party model, the Scandinavian multi-party systems fall short of a thoroughgoing majority-opposition confrontation. Stjernquist characterizes the Swedish opposition parties' tactics thus: “in election campaigns, the English approach; in parliament and elsewhere, collaboration with the government in order to influence the political decision-making as much as possible”: ibid., p. 137. But the dualism is still present, at least in elections, whereas, until 1967, it was non-existent in France. Maurice Duverger has recently stated the thesis that present-day “centrism” in France (i.e., the joining of the centers against the extremes) is nearly unique to France among present-day European countries: La Démocratie sans le Peuple (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1967), pp. 129–132.

16 Unlike a legislative election, a presidential election forces the parties to choose between a small finite number of individual candidates rather than an indefinite number of potential coalitions. With de Gaulle as one of the candidates, parties in the center of the spectrum either had to fall in behind him or support an active, critical opponent. For accounts of the pre-election soul-searching experienced by the parties see Andrews, William G. and Hoffmann, Stanley, “France: the Search for Presidentialism,” in Andrews, William G. (ed.), European Politics I: The Restless Search (Princeton, N. J.: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1966), pp. 104–138 Google Scholar; and Suffert, Georges, De Defferre à Mitterrand: La Campagne présidentielle (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1966).Google Scholar

17 L'Année politique, économique, sociale et diplomatique en France, 1956–1965 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1957–1966). MacRae used roughly the same criterion for identifying important votes in his study of the National Assembly in the Fourth Republic. For his persuasive justification, see Parliament, Parties and Society in France (New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1967), pp. 339–341. Only the votes for which pour and contre totals were given in the “Politique intérieur” section of the yearbook were used in the present study. Several votes with excessive numbers of absences and abstentions were omitted, as were all votes in which more than 90 percent of the deputies voting positively or negatively voted the same way. Deputies' votes were tabulated from Journal officiel de la République française, Débats parlementaires, Assemblée Nationale, 1956–1965.Google Scholar

18 Seven votes were mentioned in L'Année politique for the weeks immediately following the Pflimlin investiture (#974, #977, #986, #989, #990, #993, and #1000). These votes were omitted from the study by my oversight. They include the investiture of General de Gaulle and the granting to him of “pleins pouvoirs.”

19 A special computer program was written in Fortran by Mr. Joel S. Rose to find scalable subsets in the prescribed fashion. This overcame the almost insurmountable complexities involved in trying to find the largest scalable sub-set from an 83×82/2 matrix.

20 The four non-scalar votes for the Legislature (with substantive categories in parentheses) were #211 (Eu), #840 (Po), #841 (Po), and #972 (G). Only #972 was a confidence vote; it was the investiture vote for the Pflimlin Government. The brace of “Political” votes comes the closest to a small homogeneous scale of any of the subsets. Both votes relate to electoral reform.

21 Roll calls were originally coded according to the criterion that the side on which members of the Government voted should be considered “positive” and the other side “negative.” For the two Fifth Republic legislatures, with members of the Government no longer doubling as deputies, the side of the motion supported by the majority of the Gaullist UNR was taken as the positive side. The computer program included a feature whereby pairs of items were flagged if they would scale with the reversal of signs of one of them, thus making it possible to catch items for which the sign criterion was inappropriate. One item (#692) was actually added to Scale B (1956) in this fashion. All of the various types of absences and abstentions by which the Journal Officiel classified deputies were combined into a single residual code category.

22 Both were motions which tended to rally the left and center of the Assembly against the right, an untypical occurrence after late 1956, since the left was usually divided in the period covered by Scale A.

23 This refers to the median confidence vote in the order in which confidence votes are arrayed in the above table listing Scale A votes.

24 The procedure for collapsing scale categories departs from that suggested by MacRae in “A Method for Identifying Issues and Factions from Legislative Votes,” op. cit. The method used here proceeds from the assumption that, in a parliamentary legislative body, the vote on a given scale which most clearly characterizes a sub-set of legislators is the one at which it first votes against the position advanced by the Government. Thus, as we move from the positive to the negative side of a deputy's voting pattern on the scale, he will be scored according to the point at which the first negative vote that can be deemed scalar appears. This follows the conventional pattern if there are no errors or abstentions on the margin. Thus:

is scored as 5, as is

Errors on the margin pose problems for any scoring convention. The way to mentally “sweep an error under the rug” is to pretend that the vote is what it should have been to conform to the pattern. But what of the following kind of pattern?

Here the problem is whether to treat the marginal + as a – or the marginal – as a +. Under the assumption prevailing in this study we attach greater significance to the negative vote. Thus the + is converted to a – and the deputy scores 4. (Incidentally, deputies are given no score if they have more than 10 percent errors or more than 40 percent absences and abstentions.) Absences and abstentions on the margin are treated as if they were positive votes, since the vote against the Government is deemed the “harder” alternative. Thus,

is scored as 5.

Given the importance attached to the first negative vote, we can identify each class on the scale by the vote which separates it from the next most positive class. If a class contains less than two percent of the deputies we must choose whether to combine it with the class to its positive side or with that to its negative side. To resolve this problem the “identifying vote” for the small class is compared with each of its neighbors to see which pair yields the higher φ/φ max coefficient. Pairs of items with the higher coefficients are combined as are the classes of deputies identified with them. I do not recommend the use of these conventions for other kinds of studies. The particular purpose of the present study—measurement of majority and opposition voting—seemed to warrant it.

25 See L'Année politique, 1956, pp. 4–22.

26 Ibid., pp. 80, 97–99.

27 #693, immediately to its negative side, was the unsuccessful second investiture attempt of Guy Mollet, thus not a confidence vote for an active Government.

28 #104 is chosen for the dividing line between the consistent majority and the intermediates rather than #692, which is the unsuccessful investiture attempt of Antoine Pinay.

29 The interpretation of the 1956 Legislature advanced here does not differ significantly from MacRae's intra-party scale analysis of the National Assembly in the Fourth Republic. See Parliament, Parties and Society in France: 1946–1958, op. cit., pp. 157–178. Inter-party scale analysis does seem to bring out two features more clearly: (1) the sharp break in voting alignments occurring in late 1956; and (2) the unidimensional pattern extending through 2½ governments from late 1956 to April 1958. MacRae does note differences in scalar patterns for both the “Moderates” (Independents and Peasants) and the “Radicals” (Valois Radicals and UDSR) as between the early and late parts of the Mollet Government. He sees the cut-off point for the Radicals, however, as being in the Spring of 1957, rather than in late 1956: ibid., pp. 171–173. Yet, in December, 1956, a substantial proportion of the Mendèsists voted against three confidence motions on the budget (#365, #366, and #367), although they were not yet joined by Mendès-France himself. (Indeed his three positive votes on these motions were non-scalar with respect to the rest of his voting pattern and made it impossible to give him a score.) This break-away behavior by a significant group of Radicals on motions of confidence certainly must have meant a basic re-positioning of deputies within the party by late 1956.

Beyond very general statements it is difficult to compare MacRae's results with those for this study for three reasons: (1) Scale analysis is more sensitive to slight variations in individual voting patterns within individual parties than within the Assembly at large, since individual inconsistencies are counterbalanced in the latter by the monolithic consistency of large parties like the Communists and the Socialists. (2) Since he could only employ roll call votes on which the party was divided internally, MacRae's sample of votes consulted for any given party was likely to be smaller than that used here for the Assembly as a whole and unlikely to be at all representative of it. (3) MacRae endeavored to reduce roll calls to nearly dichotomous items by interpreting abstentions as either positive or negative votes, or by creating two items out of one, interpreting the abstentions first as + votes and second as – votes. This certainly makes for a more rigorous pre-condition to scaling than is true of the procedure used in the present study, wherein abstentions were ignored in the original pairing and in the eventual cr calculation. However, I feared that an arbitrary assignment of abstentions to the + or – side would distort the pattern of majority and opposition voting for a string of items. Admittedly, however, in the procedure used here distortion occurs in the scoring, where it is also necessary to interpret abstentions as + or – votes. I consider this method (see footnote 22, supra) less arbitrary than MacRae's for the purpose of capturing the relative positions of deputies vis-à-vis the Government, which was not MacRae's central purpose. For MacRae's scaling procedures see ibid., pp. 339–352.

30 The 65 votes examined are from a total of 196 taken during the Legislature.

31 Of the five votes on the third scale, three deal with procedural questions (#5, #10 and #18) and two concern agriculture (#30 and #195). For speculation as to the meaning of this juxtaposition, see David M. Wood, “The Shifting Bases of Legislative Majorities in the French Fifth Republic: A Guttman Scale Analysis,” paper delivered at the 1966 meeting of the Midwest Conference of Political Scientists, Chicago, April 30, 1966. The 13 non-scalar votes are widely distributed among substantive types. Three are budget votes (#63, #165 and #166), two deal with North Africa (#74 and #184), two with social welfare measures (#99 and #100), two with agriculture (#106 and #109), one with procedure (#3), one with overseas territories (#77), and one with veterans (#118). One of the North African votes (#184) was a censure motion. It differed in voting distribution from that of the main 1958 scale (see Table 4, infra) only in the inversion of position of some of the Algerian and Independent deputies toward the negative end of the scale.

32 Careful analyses of voting trends on censure motions during the 1958 Legislature appear in Parodi, Jean-Luc, Les rapports entre le Législatif et l'Exécutif sous la Ve République (Paris: Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, 1962)Google Scholar; and Macridis, and Brown, , Supplement to “The De Gaulle Republic” (Homewood, Ill.: The Dorsey Press, Inc., 1963), pp. 58–61.Google Scholar

33 See Andrews and Hoffmann, op. cit., pp. 88–98.

34 A good capsule description of the re-alignment following the 1962 elections is to be found in L'Année politique, 1962, pp. 140–141.

35 There was a total of 254 votes taken during the four-year period studied. The two non-scalar votes are #75 (housing) and #234 (North Africa). Neither was a motion of censure.

36 As an additional indicator of the high degree of unidimensionality, the 1962 scale has the highest overall coefficient of reproducibility of the five scales examined here:

37 There is no requirement for an investiture vote in the 1958 Constitution. Nevertheless, the vote on the Premier's policy statement can be regarded as an expression of the degree of support existing at the outset of the Legislature for the particular Government which Pompidou headed.

38 The Gaulliste themselves object to the “rightist” label, and their voting behavior in the 1956 and 1958 legislatures certainly strengthens their claim to “centrist” status. Unfortunately for their claim, if not for their majority status, they emerged from the 1962 elections with nothing but thin air to their right. The Républicains Indépendants were the least right-of-center of the old Independents, and the Centre Démocratique was predominantly composed of MRP, or center, deputies. All three groups (UNR, RI and CD) could be said to occupy roughly the same ideological space: from dead center to moderate right. To be sure, de Gaulle's foreign policy puts the Gaullists to the left of center on the spectrum, but their outlook on the Constitution, with emphasis upon a strong executive, is traditionally a right-wing position in France. Thus, the extremes of their “ideological profile” go beyond those of the other two parties; but, if it were possible to devise a multi-dimensional measure of ideological position, it is likely that the UNR would be close to the other two parties, at least in a measure of central tendency. The impressions of the author are drawn from interviews in Paris with candidates of the “Fifth Republic” alliance and the Centre Démocratique during the campaign for the March, 1967 legislative elections, as well as from examination of campaign statements of the party leaders appearing in Le Monde during the campaign. A useful pre-election compilation of party positions on the primary issues of the moment is to be found in Le Dossier politique de l'Electeur français (Paris: Editions Planète, 1967).

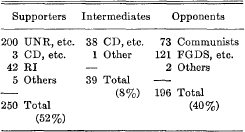

39 It is possible to hazard an assessment of the distribution of deputy types at the outset of the 1967 Legislature. An estimate can be made from the analysis of votes for the first censure motion of the Legislature appearing in Le Monde, May 23, 1967, p. 9. By assuming (1) that the members of the group Progrès et Démocratie (primarily the Centre Démocrate) who voted for the motion are intermediates, (2) that members of the two left groups, Communists and Fédération des Gauches are consistent opponents, (3) that deputies who did not vote for the motion are consistent supporters; and using their earlier scale scores to classify the isolated deputies who voted for the motion, one arrives at the following distribution:

(One isolated deputy voting for the motion, who was not a member of the 1962 Legislature, is not included in this break-down.) Here we see the further advance of the opposition and the further decline of the intermediates, with the growth trend of the majority being halted and somewhat reversed. Despite the last development, however, it is striking to note the 7 percent increase in the combined strength of the majority and opposition at the expense of the intermediates.

Too much stock should not be placed in these figures as predictive of what the character of the new Legislature will be. The characterization of the Communists as consistent opponents may not withstand the test of events if the Assembly faces any foreign policy issues. As early as April, 1966 a censure motion advanced by the Socialists attacking de Gaulle's NATO policy failed to get the support of the Communists, thus joining the two ends of the 1962 scale against the middle: see L'Année politique, 1966, pp. 34–37. This should be sufficient warning, incidentally, that the “1962 scale” characterizes only the first three years of the 1962 Legislature and not necessarily the entire four, the year 1966 not having been examined.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.