The twentieth century media landscape centered on print and television media and was characterized by high costs of entry for news producers and a limited set of choices for news consumers (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004; Mutz and Martin Reference Mutz and Martin2001; Prior Reference Prior2007). In the Internet era, these barriers to entry and constraints on choice have fallen away, resulting in a massive expansion in the number of accessible news sources (Hindman Reference Hindman2008; Metzger et al. Reference Metzger, Flanagin, Eyal, Lemus and McCann2003; Munger Reference Munger2020; Pennycook and Rand Reference Pennycook and Rand2019; Van Aelst et al. Reference Van Aelst, Strömbäck, Aalberg, Esser, de Vreese, Matthes and Hopmann2017). The public can now see political coverage from a vast array of media—local, national, even foreign news outlets—many with which they are unfamiliar.

Unknown media outlets are notable, in part, because they represent potential sources of misinformation and slanted coverage not previously available in many settings (Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Reference Guess, Nyhan and Reifler2020; Lazer et al. Reference Lazer, Baum, Benkler, Berinsky, Greenhill, Menezer and Metzger2018). Here we focus on newly available, and largely unknown, local and foreign media outlets that have introduced distinctive political news coverage into local and national politics. In local politics, the decline of newspapers (Darr, Hitt, and Dunaway Reference Darr, Hitt and Dunaway2018; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015; Reference Hayes and Lawless2018; Peterson Reference Peterson2021) coincides with the emergence of networks of hyperpartisan local news websites. These outlets push a partisan agenda and often have no presence in the communities they purport to cover (Mahone and Napoli Reference Mahone and Napoli2020). In national politics, online news use means foreign propaganda can easily reach American audiences. This prompted the U.S. Department of Justice to require RT, an English-language news source sponsored by the Russian government, to register as a foreign agent in 2017 (Stubbs and Gibson Reference Stubbs and Gibson2017).

Although the emergence of unfamiliar news sources is relevant to many political settings, the implications of the public’s encounters with them remain unclear. Previous studies primarily consider sources with established reputations. They find that trustworthy news outlets can more effectively influence opinion than media viewed as untrustworthy (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Hovland, Janis, and Kelley Reference Hovland, Janis and Kelley1953; Ladd Reference Ladd2010; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2000; Petty and Cacioppo Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986), that the public resists messages from media they associate with their political opponents (Hopkins and Ladd Reference Hopkins and Ladd2014; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), and that media brands influence news use (Iyengar and Hahn Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Stroud Reference Stroud2008).

Given the importance of media reputations, how does the public respond to unknown news sources that lack defined profiles? We consider how source familiarity influences two aspects of the political communication process. The first are decisions about whether or not to consume news from an outlet. The second are responses to its political coverage. At both stages we hypothesize unfamiliar sources will be disadvantaged relative to familiar media, with people more likely to avoid their coverage and more resistant to messages it contains.

We examine the use of, and response to, news from unfamiliar and familiar media sources in two large survey experiments (n = 6,042 and n = 5,068) on diverse national samples.Footnote 1 The experiments consider several issues where unfamiliar sources are relevant: state tax policy, perceptions of polarization in American politics, views on the integrity of the 2020 US presidential election, and the perceived threat of cyberattacks to the government and economy of the United States. On each topic we elicited news preferences before randomly assigning respondents to see a story from a familiar source, view the same article attributed to an unfamiliar outlet, or not see any news (i.e., a “patient preference” design; see Arceneaux and Johnson Reference Arceneaux and Johnson2013; de Benedictis-Kessner et al. Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Baum, Berinsky and Yamamoto2019; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013). This lets us measure the public’s willingness to seek news from unfamiliar media, estimate the effect of encountering unfamiliar news sources on public opinion, and compare it with a familiar media outlet’s influence on the same issue.

The experiments reveal source familiarity plays a large role in news choice, with people far less willing to select coverage from unfamiliar media than from sources with which they are familiar. Conditional on exposure, however, the experiment shows unfamiliar local and foreign media sources can influence public opinion. Contrary to our expectations, the effects of exposure to these unknown sources are similar to those of mainstream media with much greater familiarity when pooling the five studies into a summary estimate. Moreover, the influence of unfamiliar news sources is not confined to those who seek them out. Even among people who prefer to avoid unfamiliar media, encountering their coverage affects opinion.

Our results make important contributions to understanding political communication in the contemporary high-choice media environment. Previous work emphasizes media outlet reputations matter due to how they condition responses to news coverage showing, for instance, the public’s resistance to messages from media they perceive as untrustworthy (Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2000; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Given exposure to their coverage, we instead find unfamiliar news sources to be as effective at shifting public opinion as familiar media with established reputations. We attribute this to two developments. First, the public evaluates these unfamiliar news sources in a neutral, rather than negative, manner. Second, sustained declines in media trust over the past several decades have reduced the premium for familiar media relative to unknown sources. Rather than resistance to news from unknown sources, we find avoidance of unfamiliar news outlets is the primary factor limiting their contemporary political influence.

Source Reputations and Media Effects

Holding a speaker’s message constant, an expansive literature finds that communicators regarded as credible and likable are more persuasive than those that lack these characteristics (Aronson, Turner, and Carlsmith Reference Aronson, Turner and Carlsmith1963; Chaiken Reference Chaiken1980; Hovland and Weiss Reference Hovland and Weiss1951; Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Mondak Reference Mondak1993; Pornpitakpan Reference Pornpitakpan2004). Such broad arguments about the importance of source reputations receive further support in studies of political media. Miller and Krosnick (Reference Miller and Krosnick2000) and Ladd (Reference Ladd2010) find those low in media trust are less responsive to messages contained in political coverage. Druckman (Reference Druckman2001) shows issue frames from an untrustworthy news source (the National Enquirer) are ineffective, whereas the same frames delivered by a trustworthy source (the New York Times) can change public opinion (see also Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Petty and Cacioppo Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986). Relatedly, source reputations matter insofar as the public resists messages conveyed by media they perceive as incongruent with their political predispositions (Hopkins and Ladd Reference Hopkins and Ladd2014; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013; Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Other research considers how reputations affect news exposure. Partisan cable channels attract those sharing their party label and repel out-party members (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013; Martin and Yurukoglu Reference Martin and Yurukoglu2017; Stroud Reference Stroud2011). Similarly, online outlets with distinctive reputations have a partisan divide in their audiences (de Benedictis-Kessner et al. Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Baum, Berinsky and Yamamoto2019; Iyengar and Hahn Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Tyler, Grimmer, and Iyengar Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2021). Affinity for copartisan media appears to operate via perceived trustworthiness, as people continue to rely on copartisan outlets in news selection experiments when monetary incentives are introduced for correctly answering political knowledge questions (Luca et al. Reference Luca, Munger, Nagler and Joshua2021; Peterson and Iyengar Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2021).

Common to research on communication effects and news use is a focus on media with established reputations. These studies require that the public have a sense of the media’s overall trustworthiness (Archer Reference Archer, Krisitin and Goethals2020; Goidel, Davis, and Goidel Reference Goidel, Davis and Goidel2021; Ladd Reference Ladd2012) or the reputations of individual sources (Baum and Gussin Reference Baum and Gussin2007; Peterson and Kagalwala Reference Peterson and Kagalwala2021), leading to the study of well-known outlets such as MSNBC, Fox News, CNN, or USA Today (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Hinckley and Horiuchi2019; Coe et al. Reference Coe, Tewskbury, Bond, Drogos, Porter, Yahn and Zhang2008; Levendusky and Malhotra Reference Levendusky and Malhotra2016; Martin and Yurukoglu Reference Martin and Yurukoglu2017; Mummolo Reference Mummolo2016).

Unfamiliarity as an Element of Media Reputations

While established media are important information sources, the ease of entry into the digital media landscape has greatly expanded the number of relevant political news options (Hindman Reference Hindman2008; Metzger et al. Reference Metzger, Flanagin, Eyal, Lemus and McCann2003; Munger Reference Munger2020; Pennycook and Rand Reference Pennycook and Rand2019). The array of media the public can now encounter far exceeds the number of sources they are aware of. This makes unfamiliarity, like trustworthiness, a facet of media reputation that merits attention.

A 2019 study by the Pew Research Center illustrates this point (Jurkowitz et al. Reference Jurkowitz, Mitchell, Shearer and Walker2020). Pew surveyed a nationally representative sample about their awareness of 30 news sources representing popular political media from across the ideological spectrum. The average respondent was unfamiliar with 31% of these sources. Even among these prominent political news outlets, many brand reputations were not broad, as only 11 sources were known by 80% or more of respondents (see also Pennycook and Rand Reference Pennycook and Rand2019).

This limited awareness of media reputations coexists with a news environment in which people can potentially encounter a vast number of media outlets. While it is difficult to precisely characterize the number of sources relevant for contemporary news use, recent studies show the breadth of options. Dilliplane, Goldman, and Mutz (Reference Dilliplane, Goldman and Mutz2013) measure exposure to 49 different political television programs. Flaxman, Goel, and Rao (Reference Flaxman, Goel and Rao2016) report the Open Directory Project lists nearly 8,000 web domains providing news coverage. Based on lists of prominent news websites, Peterson, Goel, and Iyengar (Reference Peterson, Goel and Iyengar2021) consider web traffic to 355 political news domains and Gentzkow and Shapiro (Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2011) do so for 1,379 news outlets. Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic (Reference Bakshy, Messing and Adamic2015) examine content sharing patterns for 500 news websites on Facebook. Although news use remains concentrated among prominent outlets (Guess Reference Guess2021; Hindman Reference Hindman2008; Reference Hindman2018; Tyler, Grimmer, and Iyengar Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2021), this shows media sources with plausible political relevance now number in the hundreds, if not thousands, far beyond the set of news outlets with clear public reputations.

Source Familiarity and News Choice

Our study concerns how political communication—both exposure to news and responses to media coverage when it is encountered—proceeds when incorporating unfamiliarity as an element of media source reputations. We first consider how unfamiliarity influences news choice. Although some may avoid familiar media they distrust (Tsfati and Cappella Reference Tsafi and Capella2003) or be inattentive to media reputations, previous work suggests the lack of an established brand is an impediment for unfamiliar news sources competing against more familiar alternatives.

Based on the “recognition heuristic,” in which people make positive inferences about an object’s traits based on recognizing it (Goldstein and Gigerenzer Reference Goldstein and Gigerenzer2002; Kam and Zechmeister Reference Kam and Zechmeister2013), Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders (Reference Metzger, Flanagin and Medders2010) argue mere familiarity with a news organization’s logo and name will enhance its credibility relative to unknown media outlets (see also Sundar Reference Sundar, Metzger and Flanagin2008). This suggests negative assessments of their credibility will make unknown media outlets less appealing information sources. Furthermore, unlike unfamiliar outlets, established media sources have had the opportunity to secure a routine place in people’s news diets, serving as a habitual default when they make news use decisions (Mutz and Young Reference Mutz and Young2011; Stroud Reference Stroud2008).

Ideological considerations can also advantage media with distinct partisan brands. In today’s highly segmented media landscape, news outlets cater to political views across the ideological spectrum (Mullainathan and Shleifer Reference Mullainathan and Shleifer2005). Based on this, we expect some of the familiar sources available when people select media coverage will have cultivated positive reputations, offering an advantage relative to outlets without a profile due to the anticipated congeniality of their news coverage.

Empirically, Iyengar and Hahn (Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009) demonstrate the value of familiar news source reputations. First, they find people continue to rely on popular political media brands even for coverage of nonpolitical topics (see also Stroud Reference Stroud2011). Second, when news stories are presented without a source, interest in them is lower. The problem anonymous news reports face in attracting interest suggests similar issues for unknown media outlets.

Expectations: Source Familiarity and News Choice

Based on prior literature, we expect familiar outlets will be advantaged, relative to unfamiliar outlets, at the news selection stage. This leads to our first hypothesis.Footnote 2

H1: Familiarity with a news source will increase interest in consuming its coverage.

Responding to News from Unfamiliar Media

Beyond news exposure, we also consider how source familiarity conditions responses to political news coverage. What happens when the public encounters news from unknown media sources? Two perspectives emerge from previous research on source credibility that examines the issue in a variety of contexts.

Here the recognition heuristic suggests unfamiliar sources will be evaluated as untrustworthy and, accordingly, be ineffective at influencing public opinion. Pennycook and Rand (Reference Pennycook and Rand2019) crowd-source assessments of online news sources and find unfamiliar hyperpartisan outlets are perceived as less credible than mainstream media, aligning with how Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders (Reference Metzger, Flanagin and Medders2010) found people discussed unfamiliar news sources in their focus groups. Indicative of the ineffectiveness of unknown sources, Weisbuch, Mackie, and Garcia-Marques (Reference Weisbuch, Mackie and Garcia-Marques2003) show a speaker an audience has encountered before is more influential than an unknown speaker. Coan et al. (Reference Coan, Merolla, Stephenson and Zechmeister2008) observe limited cue effects from minor parties (i.e., the Green party) among those unfamiliar with them (see also Brader, Tucker, and Duell Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2012). Dragojlovic (Reference Dragojlovic2013) finds cues from unknown foreign politicians are ineffective, whereas recognizable foreign leaders can move public opinion (see also Hayes and Guardino Reference Hayes and Guardino2011).

Others claim unfamiliar sources are evaluated in a neutral manner, potentially enabling them to persuade the public. Weber, Dunaway, and Johnson (Reference Weber, Dunaway and Johnson2012) find campaign ads from an unknown interest group are more effective than attributing them to an established, but polarizing, interest group (see also Brooks and Murov Reference Brooks and Murov2012; Jungherr et al. Reference Jungherr, Wuttke, Mader and Schoen2021). Broockman, Kaufman, and Lenz (Reference Broockman, Kaufman and Lenz2021) show people respond favorably to interest group candidate endorsements, even with no idea of the group’s positions. This happens because they assume the stances of unfamiliar groups align with their own.

Closest to our focus, several studies ask people to assess the trustworthiness of unfamiliar or fictional news outlets. Although coverage from these sources is typically evaluated as less credible than coverage from real sources (but see Dias, Pennycook, and Rand Reference Dias, Pennycook and Rand2020), news from fictional outlets with innocuous names (e.g., “DailyNewsReview.com”) is still typically rated as relatively trustworthy (Bauer and von Hohenberg Reference Bauer and von Hohenberg2020; Greer Reference Greer2003; Sterrett et al. Reference Sterrett, Malato, Benz, Kantor, Tompson, Rosenstiel, Sonderman and Loker2019).

A final point is that even studies emphasizing source credibility’s importance observe instances in which untrustworthy sources move opinion. In one such case, Hovland, Janis, and Kelley (Reference Hovland, Janis and Kelley1953, 36) note “presumably the arguments contained in the communications produced large enough positive effects to counteract negative effects due to the communicator.” Dual process models distinguishing heuristic (based on source cues) and systematic (based on message content) processing conclude source cues have a substantial influence on public opinion in most ordinary circumstances, but that an unreliable messenger may not fully undermine an otherwise effective message (Chaiken Reference Chaiken1980; Petty and Cacioppo Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986).

Expectations: Effects of Familiar and Unfamiliar Media

We anticipate both familiar and unfamiliar news sources will influence opinion when a news article is attributed to them. For familiar sources, this follows from prior demonstrations that positive source reputations facilitate influence (Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Hovland, Janis, and Kelley Reference Hovland, Janis and Kelley1953). The expectation for unfamiliar media is less clear, but we see previous work as supporting the notion that unfamiliar news sources may influence opinion not because they have acquired a favorable reputation but because they lack an overly negative one (Weber, Dunaway, and Johnson Reference Weber, Dunaway and Johnson2012). This produces our second and third hypotheses.

H2: Exposure to a news article from a familiar media source will move opinion toward the views in its coverage.

H3: Exposure to a news article from an unfamiliar media source will move opinion toward the views in its coverage.

We also anticipate heterogeneity in these effects. The political communication literature’s emphasis on the effectiveness of messages from sources perceived as credible and trustworthy suggests familiar sources will be more effective than unfamiliar sources. This leads to our fourth hypothesis.

H4: Exposure to a news article from a familiar media source will be more influential than exposure to the same article from an unfamiliar media source.

Who Do Unfamiliar Media Outlets Influence?

Finally, we consider heterogeneity in responses to coverage from unfamiliar news sources among those who would (or would not) seek them out. One theme of extant work on misinformation is that some characteristics (e.g., lack of cognitive reflection, high need for certainty) predict both a willingness to seek out unreliable information sources and a tendency to credulously accept claims these outlets make (Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Reference Guess, Nyhan and Reifler2020; Federico and Malka Reference Federico and Malka2018; Mosleh et al. Reference Mosleh, Pennycook, Archar and Rand2021). Relatedly, some studies of partisan media find people resist messages from cross-cutting sources they would prefer to avoid if forced to encounter such coverage (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013). This bundled perspective suggests the acceptance of messages from unfamiliar media should be concentrated among those interested in their coverage but resistance should be stronger among those avoiding unfamiliar news sources.

However, it is also possible news preferences and information processing operate in a more decoupled manner. The decision to avoid an unfamiliar source may not mean people would resist the source’s coverage if they encountered it. Recent political psychology work supports this perspective by arguing that partisan differences in misinformation are not due to innate between-group differences in willingness to accept inaccurate claims or follow partisan cues but derive instead from differential patterns of information exposure (Guay and Johnston Reference Guay and Johnston2021; Ryan and Aziz Reference Ryan and Aziz2021). In other words, on issues where they exhibit less misinformation, Democrats may not be able to more effectively resist misinformed claims than Republicans, they may just more successfully avoid such content. Similarly, some studies of partisan media find cross-cutting exposure to out-party news sources can influence opinion (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Hinckley and Horiuchi2019; Conroy-Krutz and Moehler Reference Conroy-Krutz and Moehler2015; de Benedictis-Kessner et al. Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Baum, Berinsky and Yamamoto2019; Levy Reference Levy2021; Martin and Yurukoglu Reference Martin and Yurukoglu2017), suggesting an aversion to consuming a source’s coverage does not preclude being influenced by it.

Expectations: Conditional Effects of Unfamiliar Media

Either because they are inattentive to source cues or have a desire to avoid established media, our fifth hypothesis is that those interested in seeking out unfamiliar news sources will respond to their coverage.

H5: Exposure to a news article from an unfamiliar media source will move opinion among those who select it.

We have mixed expectations about the effects of unfamiliar media among those who prefer to avoid them. One possibility is that unfamiliar sources will not influence this group, with their coverage evaluated similarly to news from outlets with negative reputations. Alternatively, unfamiliar sources could move opinion even among those who prefer to avoid them. This may occur if unfamiliar sources are perceived in a neutral manner, leading to less resistance among the group avoiding them. We lay out competing expectations about the effects of unfamiliar media among this group in our sixth hypothesis.

H6a: Exposure to a news article from an unfamiliar media source will not move opinion among those who prefer to avoid it.

H6b: Exposure to a news article from an unfamiliar media source will move opinion among those who prefer to avoid it.

Unfamiliar Local and Foreign News Sources

Before turning to experiments testing these hypotheses, we discuss the unfamiliar news sources studied here. While many unfamiliar news sources merit consideration, we focus on hyperpartisan local news websites and RT, an English-language media outlet financed by the Russian government. This is because these sources are both unfamiliar and provide distinctive political coverage in important policy domains.

First, the decline of newspapers has opened opportunities for new, online local political coverage (Darr, Hitt, and Dunaway Reference Darr, Hitt and Dunaway2018; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015; Reference Hayes and Lawless2018; Peterson Reference Peterson and Allamong2021). This shift has enabled hyperpartisan news outlets to enter the local media market. Mahone and Napoli (Reference Mahone and Napoli2020) document networks of hundreds of local news websites that, despite names conveying a geographic affiliation, typically have a limited local presence and provide ideologically slanted political coverage. In one notable instance, a false story criticizing Hillary Clinton published by the “Denver Guardian,” a website created months before and with no ties to the city, was widely shared on social media during the 2016 election (Lubbers Reference Lubbers2016). Such unfamiliar local outlets may be able to leverage the public’s positive views of local media to push a partisan agenda (Martin and McCrain [Reference Martin and McCrain2019] study this in local TV news).

Second, we consider foreign news exposure, a possibility given how Internet access has relaxed geographic constraints on news use. We focus on RT (formerly Russia Today), an English-language media outlet sponsored by the Russian government, because it allows Americans exposure to foreign propaganda through RT’s website, cable television channel, and the recirculation of its content on social media. RT’s coverage emphasizes themes of conflict and decline in American domestic politics and American overextension in foreign affairs (Elswah and Howard Reference Elswah and Howard2020). In important studies, Fisher (Reference Fisher2020) and Carter and Carter (Reference Carter and Carter2021) show exposure to RT can change American’s foreign policy views, but they do not compare this with the influence of domestic media or measure perceptions of RT’s reputation, topics we take up here while focusing on its coverage of American domestic politics.

One commonality of unfamiliar local and foreign news sources is their production of coverage that, in its appearance, resembles reporting produced by more familiar, mainstream news sources. For instance, Elswah and Howard (Reference Elswah and Howard2020) document RT’s reliance on professional journalists, along with political employees, to ensure the outlet’s messages are packaged in a way that appears familiar to news consumers. We see this appropriation of news styles from familiar sources as one reason to anticipate unfamiliar news outlets may be able to effectively influence public opinion. Accordingly, we incorporate this type of coverage from unfamiliar sources into our experiments and leave the public’s response to clearly unprofessional coverage from unfamiliar sources for future work.

Experimental Design

We consider the use and effects of unfamiliar and familiar media sources in two surveys containing five experiments. Table 1 describes the experimental design. The first survey had 6,042 respondents and was conducted during late January–early February 2021. It included Studies 1, 2, and 3. The second survey had 5,068 respondents and was conducted during late June–early July 2021. This survey contained Studies 4 and 5. In both cases, the samples were recruited by Lucid and drawn to match nationally representative quotas for age, gender, and ethnicity (see Coppock and McClellan [Reference Coppock and McClellan2019] on this subject pool).Footnote 3

Table 1. Summary of Experimental Designs

Before discussing each study’s topic, we outline the experimental design shared across them. In each study respondents were first presented with a menu of news options and indicated which they would prefer to read coverage from. This design lets us examine interest in different news sources and estimate the conditional effects of news from unfamiliar sources among those who would or would not choose to encounter them.

For Studies 1, 2, and 3 news selection occurred immediately before respondents saw a news article. In contrast, Studies 4 and 5 included a washout period on unrelated topics between when respondents made news selections and when they saw news articles. This change in the second survey minimizes any demand characteristics that might change how respondents evaluate the coverage they encounter, particularly from the unfamiliar sources we expect many will not have selected in the news choice tasks (but see Mummolo and Peterson [Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019] on the limited evidence for demand effects in online survey experiments.)

In the news exposure portion of the experiment, respondents encountered one of three randomly assigned conditions. The control group answered questions without news exposure. Those in the familiar source treatment read an article attributed to a large newspaper from their state (Study 1, Study 3, and Study 4) or USA Today (Study 2 and Study 5). These sources were selected due to their widespread familiarity and perceived trustworthiness and to avoid media evoking sharply polarized evaluations between Democrats and Republicans. Finally, respondents in the unfamiliar source treatment read the same article, instead attributed to a partisan news website in their state (Study 1 and Study 4), RT (Study 2 and Study 5), or a fictional news website from their state (Study 3). In Study 3 these fictional newspaper names were produced by combining the state’s name with a common newspaper title (i.e., “Times,” “Tribune,” or “News”) and selected to avoid overlapping with the names of prominent news sources available in the state.Footnote 4

We emphasized an article’s source in two ways. Respondents were initially informed of the source of the article on a separate page before encountering it. After clicking through to read the story, the outlet’s logo was prominently displayed as they read. Using a posttreatment attention check, we later confirm respondents took note of the article’s source.

The studies focused on a variety of issues where unfamiliar news sources are relevant. For Studies 1 and 4, the article criticized the tax system in a respondent’s state and noted its poor performance in a national ranking. This was based on an article from a partisan local website. We anticipate this will negatively affect opinions about state taxes.

Study 2’s article discussed partisan divisions among the mass public and politicians, emphasizing that Congressional gridlock poses an impediment to progress on major problems facing the United States. Such coverage frequently appears in Russian messaging on RT and social media (Bail et al. Reference Bail, Guay, Maloney, Combs, Sunshine Hillygus, Merhout, Freelon and Wolfovsky2020; Carter and Carter Reference Carter and Carter2021; Elswah and Howard Reference Elswah and Howard2020; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Hus, Neiman, Kou, Bankston, Kim, Heinrich, Baragwanath and Raskutti2018). We expect the article to increase perceptions of a polarized, gridlocked government and elevate pessimism about the country’s future. Others demonstrate coverage from established media sources can have this effect (Levendusky and Malhotra Reference Levendusky and Malhotra2016); we consider whether an unfamiliar media source can accomplish this.

Study 3 used an Associated Press story debunking false claims of widespread fraud in the 2020 Presidential election, wire copy likely to appear in local newspapers. Consistent with past work on correcting allegations of voter fraud (Holman and Lay Reference Holman and Lay2019; but see Berlinski et al. Reference Berlinski, Doyle, Guess, Levy, Lyons, Montgomery, Nyhan and Reifler2021), we expect the article to increase confidence in the election’s integrity.

Finally, based on RT’s coverage in the weeks preceding our second survey, Study 5’s article focused on the negative consequences of cyberattacks for the economy and government of the United States. We expect this to elevate public perceptions of the threat of cyberattacks.

These topics vary in ways that are intended to improve the generalizability of the set of experiments. Studies 1, 2, 4, and 5 use content originally produced by unfamiliar media sources to see whether it is more influential when attributed to a familiar source. Study 3 reverses this, examining whether local newspaper coverage is less influential when attributed to an unknown source, potentially making it easier to discount.

In terms of the direction in which public opinion was expected to move, the antitax messaging in Studies 1 and 4 aligns with the rhetoric of Republican elites, whereas the fact check in Study 3 pushes against false claims of widespread voter fraud endorsed by Republican politicians. Studies 2 and 5 have a less clear partisan valence, focusing on complaints about polarization in American politics and the threat of cyberattacks to the United States.

Finally, these issues offer a view of the relative effectiveness of media source reputations across topics that are likely to be more (i.e., state tax policy) or less (i.e., perceived polarization) amenable to influence from any type of media source based on the degree to which the public possesses well-formed opinions when entering the study.

Source Familiarity Predicts News Choice

We begin by examining how self-reported familiarity with a news source predicts a willingness to seek information from it. We measure source familiarity at the start of the survey, where respondents saw a checklist with the names and logos of various media outlets and indicated which they had previously heard of. We relate this familiarity measure to their news selections in the survey. Prior to the experimental treatments, respondents saw a menu of options and were asked which media outlet they would prefer to read. In Studies 1, 3, and 4 the choice set consisted of four local media sources determined based on a respondent’s state of residence (Appendix Table B1 shows each state’s source list). These were a large newspaper from the respondent’s state, a local partisan website, a nonprofit media outlet covering the respondent’s state and a fictional newspaper from their state. In Studies 2 and 5, the choice set contained five media sources. Four were chosen to represent established information sources at a variety of positions on the ideological spectrum: Fox News, Huffington Post, USA Today, and the New York Times. The fifth option was RT.

To relate source familiarity to news choice, we create separate observations for each option in a choice task. This results in 124,158 news source selections made across the two surveys. We regress an indicator variable for whether the respondent selected that news option on an indicator variable for whether they were familiar with the source. In the left column of Table 2, we assess this bivariate relationship with no controls. In the right column we include person and source fixed effects in the regression, isolating within-subject variation in familiarity with news sources and netting out fixed personal-level characteristics, such as political interest, and source characteristics, such as an outlet more appealing to everyone whether or not they previously heard of it. We display robust standard errors, clustered by respondent, to account for dependencies in each news selection (i.e., in each task choosing one option meant not selecting the others).

Table 2. Probability of Selecting News Source by Familiarity

Note: Robust standard errors, clustered by respondent; *p < 0.05.

Table 2 shows familiarity is a strong predictor of news choice across both specifications, providing support for Hypothesis 1, the expectation unfamiliar sources would be disadvantaged compared with familiar media at the news selection stage. Relative to news sources they are unfamiliar with, respondents are 26 percentage points more likely to choose a news source they reported familiarity with. Although familiarity is hardly a guarantee of selection, respondents chose news sources they were not familiar with only 9% of the time, while choosing sources they reported familiarity with 35% of the time.Footnote 5

We illustrate the substantive relevance of this difference based on familiarity by comparing it to partisanship, another strong predictor of news choice. In Studies 2 and 5, which featured national media, Republicans were 39 percentage points more likely than Democrats to select Fox News. In contrast, Democrats were 29 percentage points more likely than Republicans to select the New York Times. So, while slightly smaller, the difference in news selection predicted by source familiarity rivals the size of the partisan divide for two outlets with strong ideological reputations.

Effects of Familiar and Unfamiliar Sources

Having established source familiarity’s importance at the news selection stage, we consider its relevance for responses to news coverage. In our preregistration plans, we specified how each analysis would be conducted. For each outcome we use an index constructed by performing principal components analysis on multiple survey items addressing the article’s topic.Footnote 6 We standardize these outcomes to have mean zero and standard deviation one and orient them so that exposure to the article is expected to move respondents in a positive direction. So, for Study 1 and Study 4 higher scale values indicate more antitax attitudes, in Study 2 higher values indicate a more polarized and pessimistic view of American politics, for Study 3 higher values indicate more confidence in the integrity of the 2020 election, and in Study 5 higher values indicate more concern about the consequences of cyberattacks for the United States.

For each study, we regress the outcome on indicator variables for the familiar and unfamiliar news treatments to estimate the effect of each relative to the control group. The regressions include additional covariates specified in our preanalysis plans, such as a respondent’s partisanship and pretreatment measures related to the outcomes of each study to reduce uncertainty in the effect estimates (Clifford, Sheagley, and Piston Reference Clifford, Sheagley and Piston2021; see Appendix A). Finally, we committed to pooling the five studies into a summary estimate using a fixed effect meta analysis, weighting the effects of each study by how precisely they are estimated.

These decisions were made to increase the precision of the treatment effect estimates. We do so because, beyond how articles from unfamiliar and familiar news sources influence opinion, a primary question is whether the effect of familiar sources differs from unfamiliar sources. This requires precise estimates of each individual treatment effect to test appropriately, as we expect the difference between the familiar and unfamiliar treatment effects to be less stark then between either treatment and control.

Before proceeding, we note the familiar and unfamiliar treatments substantially differ in how aware respondents were of the outlets in them. Summarizing the five studies, only 21% of respondents had heard of outlets in the unfamiliar treatments. In contrast, 78% of respondents were aware of the sources in the familiar treatments of the experiments.Footnote 7

Experimental Results

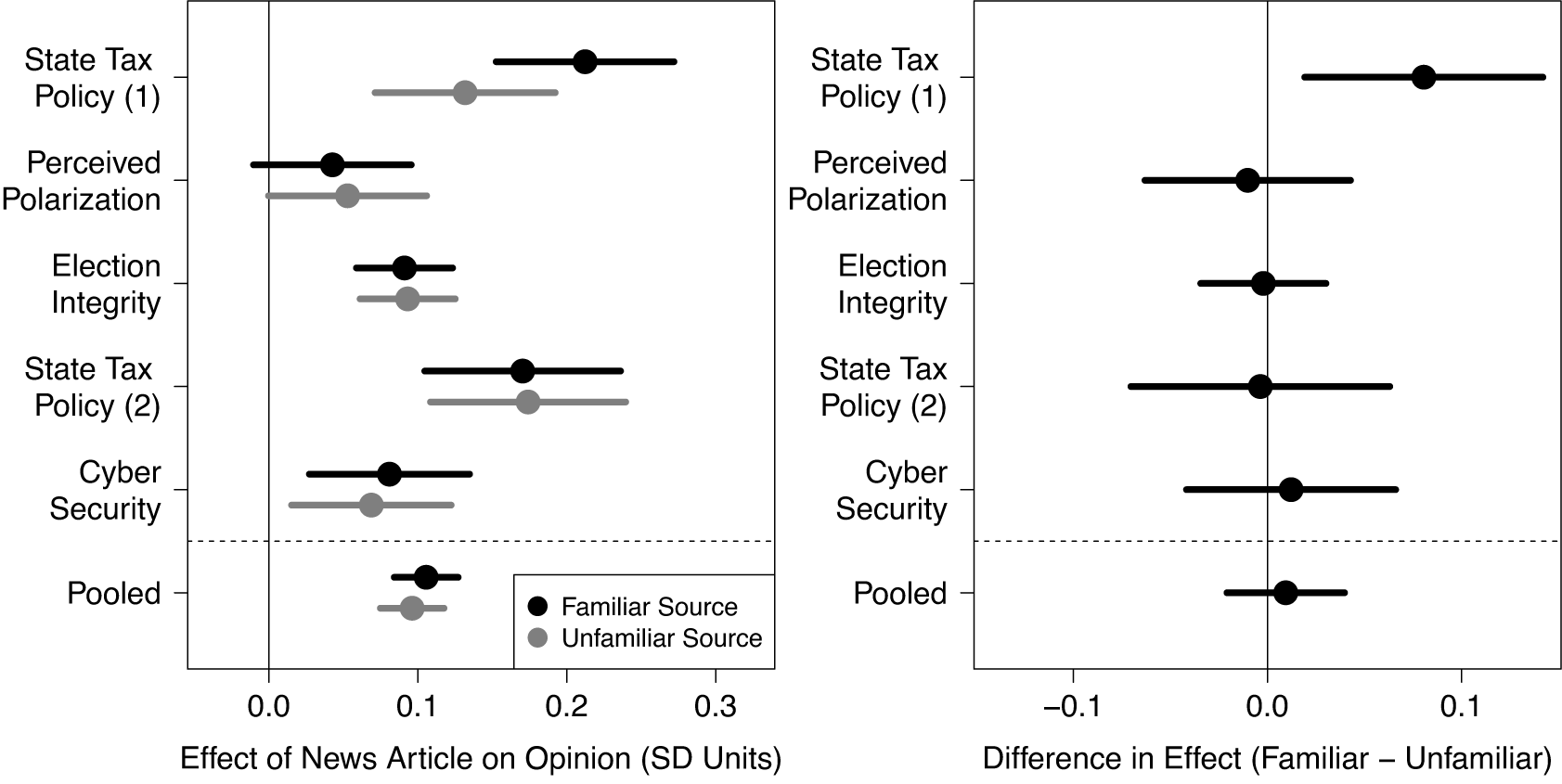

We now examine the effects of familiar and unfamiliar news sources. Figure 1 displays these estimates and the associated 95% confidence intervals.Footnote 8 We first discuss the figure’s left panel, which displays the treatment effect estimates of the familiar source (black points) and the unfamiliar source (gray points) on each topic, along with the estimate pooling the five studies. These reflect the number of standard deviations exposure to the news article moved respondents on the outcome scale compared with those in the control condition.

Figure 1. News Article Effects By Source

Consistent with our second and third hypotheses, exposure to both the familiar and unfamiliar sources influenced public opinion on these topics. In Study 1 both the familiar (0.21, 95% CI [0.15, 0.27]) and unfamiliar source (0.13, 95% CI [0.07, 0.19]) exerted a statistically significant effect, with encounters with an antitax message from either media source leading people to hold more negative views of their state’s tax policy.

The estimated effects of the two sources are of roughly similar magnitude and in the expected direction in Study 2, with those in the treatment conditions perceiving higher levels of gridlock and political polarization than those in control. However, both estimates fall short of the threshold for statistical significance we use throughout the paper (p = 0.05 for RT; p = 0.12 for USA Today), as exposure to the unfamiliar source (RT) produced an increase of 0.05 standard deviations (95% CI [−0.01, 0.11]) in perceived polarization, whereas encountering the same article from USA Today produced a 0.04 effect (95% CI [−0.01, 0.10]).

In Study 3 encountering the article debunking false claims of voter fraud increased confidence in the integrity of the 2020 Presidential election. Despite the salient nature of this issue when we conducted the study, these effects occurred whether the article was attributed to the familiar source of a large newspaper from the respondent’s state (0.09, 95% CI [0.06, 0.12]) or the unfamiliar fictional newspaper source (0.09, 95% CI [0.06, 0.13]).

For Study 4, which used the same antitax article as Study 1, the unfamiliar (0.18, 95% CI [0.11, 0.24]) and familiar outlets (0.17, 95% CI [0.11, 0.24]) both influenced opinion, this time exhibiting a similar ability to generate negative views of state taxes.

Study 5, which examined public concern over the threat posed by cyberattacks to the United States, again revealed influence from both the familiar (0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]) and unfamiliar (0.07, 95% CI [0.02, 0.12]) news outlets, with those encountering coverage expressing greater concern about cyberattacks.

In Studies 4 and 5, on the second survey, greater separation between the news selection tasks and when respondents encountered coverage did not reduce the influence of unfamiliar sources compared with more familiar alternatives. This suggests the proximity of these items in the initial survey does not contribute to the effect of unknown news sources on opinion, removing a potential explanation in which these findings are an artifact of survey design.

Pooling the five studies together, we see an effect of 0.11 standard deviations (95% CI [0.08, 0.13]) for the familiar sources and 0.10 (95% CI [0.08, 0.12]) for the unfamiliar sources. Altogether this strongly supports Hypotheses 2 and 3. Political coverage from both unfamiliar and familiar news sources influenced opinion across the different topics in the experiments.

To give a sense of the magnitude of these effects, we compare them to the divide between Republicans and Democrats in the control group. On one end, the effect of the familiar source is sizeable in Studies 1 and 4, at roughly half the size of the baseline partisan divide over state taxation. In contrast in Studies 2 and 3, which consider polarized national topics, the effects of familiar sources are only 4% and 6% the size of the partisan divide in control. So, although not always large, these studies show coverage from both unfamiliar and familiar news sources can meaningfully change opinion on a set of political issues that vary in the degree to which public opinion is malleable in response to news coverage.

While we cannot assess the persistence of these effects here, another important aspect of their political relevance, prior literature on the persistence of survey experimental treatment effects offers some guidance. We note that, while the news articles contain a mix of considerations that may shape public opinion, they all emphasize new information that respondents might otherwise not have (e.g., about the poor performance of their state on a tax ranking in Studies 1 and 4). This resembles the class of informational survey experimental effects for which scholars have hypothesized (Baden and Lecheler Reference Baden and Lecheler2012) and found (Coppock, Elkins, and Kirby Reference Coppock, Elkins and Kirby2018) greater over-time durability than those operating through other mechanisms, such as elevating the accessibility of considerations individuals were already aware of.

Heterogeneity by Source Type

We next assess the relative influence of familiar and unfamiliar news sources in the right panel of Figure 1. Here our expectation was that familiar media sources would be more influential than the unfamiliar sources. We test this by assessing the difference between the treatment effects of each source category (i.e., the difference between the effect of familiar sources and the effect of unfamiliar sources). If familiar sources are more influential, these difference in difference estimates will be positive.

Study 1 provides support for this expectation on tax policy. Here the effect of the familiar source was 60% larger than the effect of the unfamiliar source (0.08, 95% CI [0.02, 0.14]).

However, in the other studies, or when pooling together the results of the five experiments, we do not find support for this expectation. In the other experiments included on the first survey, Study 2 (-0.01, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.04]) and Study 3 (-0.01, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.03]), there is not a distinguishable difference between the familiar and unfamiliar news sources.

On the second survey in both Study 4 (-.01, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.06]), which replicated the lone experiment (Study 1) with a detectable difference between the familiar and unfamiliar sources, and Study 5 (0.01, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.07]) the difference in the effects of familiar and unfamiliar outlets is small and we are unable to reject the null hypothesis the two source types have the same effect.

This similarity extends to the pooled estimate, which indicates the effect of familiar sources is roughly 10% larger than that of unfamiliar sources but is not statistically significant (0.01, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.04]). Taken altogether, we fail to find support for Hypothesis 4 and instead observe that coverage from the two sets of sources had largely equivalent effects on public opinion, with Study 1 the lone exception.Footnote 9

While we are cautious about embracing the null hypothesis, given a failure to reject it, our study design allows us to rule out large differences in the influence of familiar and unfamiliar news sources. To show this we conduct an equivalence test—which instead sets a difference in the effects of familiar and unfamiliar news sources as the null hypothesis—to determine the range of values for which this null can be rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis that unfamiliar and familiar news sources have meaningfully similar effects. Using the 90% confidence interval of the pooled difference in the effect of familiar and unfamiliar sources allows rejection of differences outside this interval at the 0.05 level in favor of the alternative of no meaningful difference (Hartman and Hidalgo Reference Hartman and Hidalgo2018; Rainey Reference Rainey2014).

Here the 90% confidence interval on the difference in the effects of familiar and unfamiliar sources runs from -0.02 to 0.04. This means we can reject the null hypothesis of familiar sources being more influential than unfamiliar sources for any difference of more than 0.04, or roughly 35% more influential than the pooled effect of unfamiliar sources, in favor of the alternative hypothesis of no meaningful difference in the effects of the two source types. Although this does not preclude familiar outlets exerting more influence than unfamiliar sources, a valuable contribution of this study is to rule out large differences between them.

We later discuss explanations for the similar effects of familiar and unfamiliar media outlets, but one possibility we address here is that respondents were simply inattentive to a story’s source, which might explain their similar effects. In each study half the respondents reading an article were randomly assigned to an attention check. They were asked to recall the source that produced the article from a menu with four to five options. Source recall was high, as 74% of respondents in the treatment conditions correctly recalled the source they encountered (see Appendix C for results by study). Given this, inattention to source labels does not appear to explain the similar effects of unfamiliar and familiar news sources.

Summary: How Does Source Familiarity Matter?

Before proceeding to the effects of unfamiliar news sources among different groups, we revisit our expectations in light of the evidence on the overall effects of familiar and unfamiliar news sources on public opinion. We hypothesized two channels through which source familiarity might influence political communication effects. First, in an indirect channel, it might alter an individual’s propensity to consume news coverage from a source (Hypothesis 1). Second, in a direct channel, it might alter responses to the coverage a news source provides (Hypothesis 4).Footnote 10

Based on our evidence, unfamiliar and familiar news sources are distinguished almost entirely by this indirect channel. Table 2 shows people are much more likely to select coverage from a familiar source. An alternative way of describing this is to note that, summarizing the choice tasks in the five experiments, respondents selected the sources in the unfamiliar treatments only 14% of the time while selecting sources from the familiar treatments 38% of the time.

However, our assessment of effect heterogeneity in the preceding section shows there is limited evidence for a direct channel, in which familiarity alters responses to the coverage a news source provides. Pooling the various studies, we see a null effect on the difference in the effects of familiar and unfamiliar sources (0.01, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.04]). Across these studies the consequences of source familiarity for political communication appear to operate indirectly, through differences in exposure decisions, rather than directly through responses to news coverage given exposure to it.

Effects of Unfamiliar Sources by News Preference

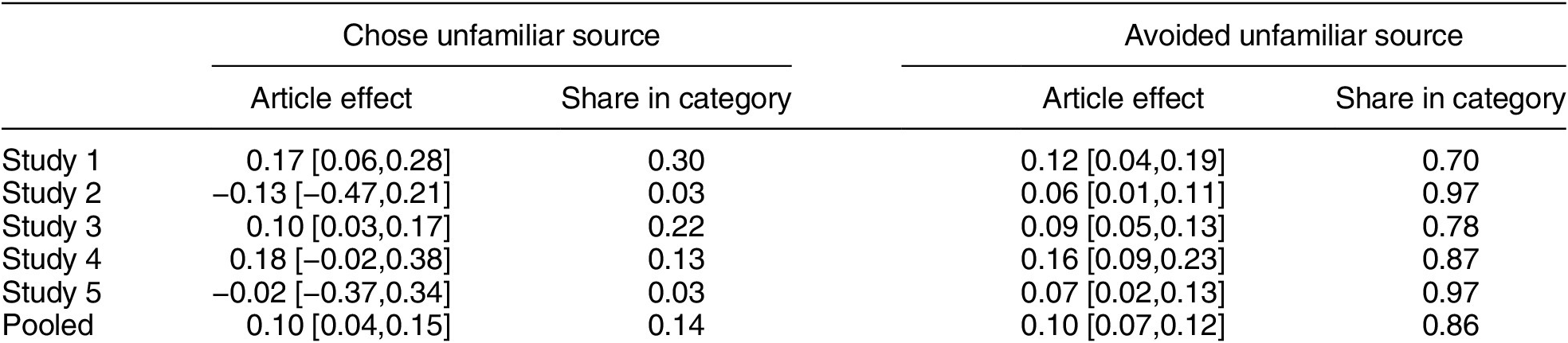

Moving beyond the average effects of each news source, we turn to the effects of unfamiliar sources among those who engage (or avoid) them when able to do so. We test our conditional hypotheses using the patient preference component of the study in which respondents revealed their preferences for consuming news from various media sources. During each study all respondents, whether they were in a condition that would expose them to news or not, were presented with a menu of news options and asked to select which source they would like to encounter information from. We use this question to separate respondents into two groups. The first are those who selected the unfamiliar news source. To test Hypothesis 5, we examine the effects of unfamiliar sources among this group. The second group consists of those who did not select the source from the unfamiliar treatment when presented with the opportunity to do so. We estimate the effects of unfamiliar sources among this group to adjudicate between our competing expectations in Hypotheses 6a and 6b.

Table 3 displays these conditional treatment effect estimates. For each study it shows the effect of unfamiliar media sources among a group, along with the associated 95% confidence interval. The table also indicates the share of the sample in that category for each study. As in the previous section, we pool the five studies together using a fixed effects meta analysis.

Table 3. Effect of Article from Unfamiliar News Source by News Preference

We first consider the left columns of the table, which display the effect of encountering unfamiliar news sources among respondents who indicated a preference for these outlets in the patient preference portion of the study. In Studies 1, 3, 4, and when pooling the results, unfamiliar media influence opinion among this group as expected. The pooled estimate indicates that, among the 14% of the sample willing to select these sources, exposure to a news article from an unfamiliar media source moved opinion by 0.10 standard deviations (95% CI [0.04, 0.15]) relative to the control group. This supports Hypothesis 5, the expectation unfamiliar outlets will influence opinion among those willing to seek them out.

The aberrant results in Study 2 and Study 5 merit some attention. In both, among the 3% of the sample selecting RT the effect of encountering its coverage is negative, though estimated with a wide confidence interval (-0.13, 95% CI [−0.47, 0.21] in Study 2 and -0.02, 95% CI [0.37, 0.34] in Study 5). We view these as idiosyncratic results of the small portion of the sample willing to select this source, which makes the estimate highly imprecise as in Study 2—for instance, it involves only 180 respondents spread across three treatment arms.

Turning to Table 3’s right columns, we consider the competing expectations about the effects of unfamiliar news sources among those who avoided such sources in the news selection task. Once again, unfamiliar news sources influenced opinion across all five studies. The effects of unfamiliar news sources on opinion, among people who avoid them in the news selection task, are statistically significant and range from 0.06 to 0.16 SDs. In the pooled results, the effect of encountering coverage from the unfamiliar source is a 0.10-standard-deviation shift (95% CI [0.07, 0.12]) in opinion among the 86% of the sample that avoided the unfamiliar news source when selecting coverage.

The combined set of results provides strong support for Hypothesis 6b. An aversion to consuming information from the unfamiliar source did not lead people to resist its coverage if they encountered it. Altogether, the pooled effects of unfamiliar sources are of similar magnitude among both those who would avoid them or seek them out. This illustrates the relevance of news selection for understanding constraints on the influence of unfamiliar sources. When choosing news, most avoided the unfamiliar source. The conditional treatment effect shows these “avoiders” would be influenced by coverage from the unfamiliar source, if they were to see it.Footnote 11

Discussion

Our experiments show unknown local and foreign media sources can influence public opinion about local and national politics. Rather than any resistance to their coverage, unfamiliar media outlets appear more hamstrung by their lack of popularity when competing for attention against established media brands. We conclude by discussing the implications of these findings.

Charitable Views of Unfamiliar Media

Conditional on exposure to their coverage, familiar and unfamiliar news outlets had a similar influence on public opinion. This was inconsistent with the pattern we expected. Why were these sources similarly effective? We see this as the combination of a tendency for respondents to evaluate unknown media in a neutral manner and the declines in trust of mainstream news sources that have occurred over the past several decades. We begin by comparing the reputations of the news sources in the familiar and unfamiliar treatment conditions in Table 4, using measures of their perceived trustworthiness and ideological bias collected at the start of the first survey.Footnote 12

Table 4. Comparing Perceptions of Media in Familiar and Unfamiliar Treatments

The familiar sources are rated, on average, at the middle of the trustworthiness scale (0.51; near the point labeled “Moderately trustworthy”), affording them an advantage of about 7% of the trust scale’s width over sources in the unfamiliar treatments (0.44). In terms of perceived ideology, respondents placed unfamiliar news sources at the “neutral” midpoint of the scale (53%) more frequently than the familiar outlets (45%). Finally, there is no difference in the perceived ideological distance—the absolute difference of a respondent’s self-placement on an ideology scale and their placement of the media source on the same scale—between the familiar and unfamiliar sources. Despite the large gulf in awareness of the two sets of outlets, in many other respects the public evaluated them similarly.

One element behind the similar effects of familiar and unfamiliar news outlets is the charitable assessments unfamiliar media sources received. People regarded unknown media as somewhat trustworthy and presumed they were moderate rather than viewing them as untrustworthy and ideologically incongruent, a finding consistent with some other work considering unknown and fictional news sources (see Bauer and von Hohenberg Reference Bauer and von Hohenberg2020; Greer Reference Greer2003; Sterrett et al. Reference Sterrett, Malato, Benz, Kantor, Tompson, Rosenstiel, Sonderman and Loker2019).Footnote 13

This differs from Pennycook and Rand (Reference Pennycook and Rand2019), who find unfamiliar fake and hyperpartisan outlets are largely mistrusted. One difference is the unfamiliar outlets in this study mimic the naming conventions of established media (e.g., the “Texas Business Daily”), which garners them more trust than the outlets Pennycook and Rand (Reference Pennycook and Rand2019) consider (e.g., “angrypatriotmovement.com”).

Explaining the sources of trust in unfamiliar media is a needed topic for future work. We suspect the domain a news source covers has some role in this, as trust is high in all the local media options we consider, with the partisan and fictional local websites receiving similar levels of trust to high-quality local nonprofit news sources (See Appendix Tables A4 and A5). Beyond this, other cues conveyed by the title and logos of unfamiliar sources are likely have a role in determining the public’s evaluation of them (e.g., Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders Reference Metzger, Flanagin and Medders2010). In Appendix Table D2, we also find that those with higher overall levels of trust in the media are more likely to trust unfamiliar news sources.

More broadly, these findings have mixed implications for research on the recognition heuristic, which motivated our theoretical expectations. Respondents trusted familiar news sources more than unfamiliar outlets (see Appendix Table D1) and were more likely to seek coverage from them, patterns consistent with the recognition heuristic. However, conditional on exposure, familiar and unfamiliar sources had similar effects on opinion. Here the difference in trust did not appear large enough to produce different responses to the coverage familiar and unfamiliar news sources provided.

Declining Trust in Mainstream Media

In addition to the neutral evaluations unfamiliar news outlets received, a second contributing factor is declines in trust of established news sources. In a manifestation of this trend, Figure 2 shows data from Pew Research Center surveys regarding the share of the public rating USA Today’s coverage as “believable.” This fell from 72% in 1986 to 48% in 2012, the most recent year with comparable question wording.

Figure 2. Believability of USA Today by Year

Note: The figure displays the share of respondents, among those providing a rating, that “Believe all or most” of USA Today’s coverage in Pew Research Center surveys from 1985 to 2012.

This large decline in trust in one of the “familiar” news outlets we study is representative of the broader decline in trust of established media over the past several decades (Archer Reference Archer, Krisitin and Goethals2020; Ladd Reference Ladd2012). Few sources today have the familiar and widely trusted reputations of the media outlets in prior studies showing the potency of source cues from familiar mainstream news sources. The familiar media in our experiments resemble this as closely as any in contemporary politics as USA Today and local newspapers are both highly familiar and at least moderately trusted by both Republicans and Democrats.

Overall, our survey shows familiar, mainstream news sources remain more trusted than others, but this advantage is small. While we cannot assess how people evaluated unfamiliar news sources in the past, we suspect the premium in trust between familiar mainstream news sources and unknown media has declined compared with earlier eras, contributing to their similar effectiveness in these experiments.

Source Familiarity in a High-Choice Media Environment

We considered two ways familiar news sources might be advantaged relative to unknown media. We found limited evidence their coverage is inherently more influential than it would be if attributed to other news sources. On the other hand, even if messages from familiar sources are not inherently more effective than those from unfamiliar outlets, we found strong support that source familiarity advantages them at the news exposure stage. This suggests the chief advantage familiar sources possess in contemporary politics is their ability to garner large audiences in a fragmented news environment, something emphasized in studies of online exposure to national news outlets (Guess Reference Guess2021; Hindman Reference Hindman2008; Tyler, Grimmer, and Iyengar Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2021) and, in a relative sense, for online exposure to local media (Hindman Reference Hindman2018).

How Might Encounters with Unfamiliar Media Occur?

Given the main impediment we identify to the influence of unknown media sources is the public’s lack of interest in consuming news from them, a question for future research becomes understanding how encounters with unfamiliar media might happen. This is all the more important as, based on the patient preference aspect of our study, even those who would ordinarily avoid such outlets still respond to their coverage if exposed to it.

Considering the news choice portion of the experiments, we find those with low levels of overall media trust were more likely than others to select the unfamiliar news sources, although the magnitude of this relationship is small (i.e., a one-standard-deviation decrease in media trust was predicted to increase unfamiliar source selection by 1 percentage point; See Appendix D), suggesting a dislike of known and familiar options makes unfamiliar news sources more attractive (see also Tsafi and Capella Reference Tsafi and Capella2003) but also demonstrating the need for further consideration of the factors beyond low overall media trust that lead people to trust and engage with unfamiliar news sources. We also note that many respondents incorrectly stated they were familiar with fictional news sources throughout the study (e.g., 35% said they had heard of Study 3’s fictional newspaper), suggesting “mistaken familiarity” might promote the use of unfamiliar sources in some cases.

Beyond low media trust, other literatures suggest ways in which encounters with unfamiliar news sources could happen. Offsetting cues, such as social media recommendations, may help an unknown media source overcome its disadvantage at the news exposure stage (Grinberg et al. Reference Grinberg, Joseph, Freidland, Swire-Thompson and Lazer2019; Messing and Westwood Reference Messing and Westwood2014; Sterrett et al. Reference Sterrett, Malato, Benz, Kantor, Tompson, Rosenstiel, Sonderman and Loker2019). Social media also creates opportunities for incidental news exposure not driven by active considerations (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic Reference Bakshy, Messing and Adamic2015; Feezell Reference Feezell2018; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Hus, Neiman, Kou, Bankston, Kim, Heinrich, Baragwanath and Raskutti2018). Other countervailing factors, like coverage of topics particularly interesting to some, might overcome the disadvantages of an unknown source label (Mummolo Reference Mummolo2016). Although more investigation is needed, this suggests several avenues through which unfamiliar news outlets can reach broader audiences.

Conclusion

Decades of research on persuasion emphasize the importance of source cues in making messages from familiar, trusted sources influential. Reconsidering this in contemporary politics, we find unfamiliar media sources without a preexisting reputation can effectively influence opinion to a degree similar to the influence of familiar mainstream media sources. Instead, the power of familiar media sources in the fragmented contemporary media environment is more in their ability to capture a large audience than in any inherent difference in the effectiveness of their messages. This similarity in effectiveness between these different sources appears to stem from declining trust in familiar mainstream news outlets, coupled with a tendency for people to provide neutral evaluations of unfamiliar news sources.

Our findings do not mean unfamiliar news sources have an unconstrained ability to shape public opinion as news sources of all types, unfamiliar or not, face limitations in their ability to move public opinion on salient issues where the public has already established well-formed opinions. However, this study reveals that on a variety of relevant local and national political issues and with news sources that range from local newspapers to a Russian-sponsored media outlet, it cannot be taken for granted that messages from unfamiliar media will be ineffective merely because they originate from an unknown source.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001234.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DIU0M1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Johanna Dunaway and Sean Westwood for helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Texas A&M’s College of Liberal Arts and Department of Political Science.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was deemed exempt from review by Texas A&M’s Institutional Review Board.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.