INTRODUCTION

In his study of African conflicts, William Reno notes a dramatic shift during the 35-year period between the early 1970s and the mid-2000s:

In 1972, supporters of an anti-colonial liberation struggle in Guinea-Bissau reported that a United Nations (UN) delegation spent seven days in rebel-held territory to learn about the administration that rebels had built to provide services to people there. To the rebels’ supporters, this was “the only government responsible to the people it has ever had.” A person suddenly transported from that “liberated zone” three and half decades forward through time would be in for a shock. UN officials in West Africa reported that in Guinea-Bissau it was hard to distinguish between state security forces and armed drug traffickers; they were allegedly in league with one another and showed little concern for the welfare of the wider population (Reno Reference Reno2011, 1).

This was not an isolated instance but part of a general trend, Reno adds:

Congo, Somalia, Nigeria’s Delta region, and many other places, suffered from what seemed to be an excess of rebel groups who were fighting one another as much as governments and now largely displayed a dearth of interest in providing people with an alternative vision of politics or even in administering them in “liberated zones” (Reno (Reference Reno2011, 1–2).

During the Cold War, competing political factions with generous access to superpower assistance pushed Global South countries into a state of semi-permanent civil war (Westad Reference Westad2005, 398). The end of the Cold War put an end to many leftist rebellions, leading to a downward shift in the occurrence of civil wars (Kalyvas and Balcells Reference Kalyvas and Balcells2010). But exactly how was this downward trend related to the shift in rebel group behavior observed by Reno? Was it connected to their ideology—and if yes, how? More broadly, why and how is ideology linked to how civil wars are fought?

Ideologies are central to conflict, yet they have only recently begun to receive sustained attention in the comparative study of civil war (Basedau, Deitch, and Zellman Reference Basedau, Deitch and Zellman2022; Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014; Hirschel-Burns Reference Hirschel-Burns2021; Keels and Wiegand Reference Keels and Wiegand2020; Leader Maynard Reference Leader Maynard2019; Parkinson Reference Parkinson2021; Thaler Reference Thaler2013; Ugarriza and Craig Reference Ugarriza and Craig2013). The same is true about the dramatic shifts undergone by civil wars over time, as suggested by Reno’s observation above (Anderson Reference Anderson2019; Kalyvas and Balcells Reference Kalyvas and Balcells2010; Stewart Reference Stewart2021).

We couple ideology with history to examine how the most important wave of twentieth-century revolutionary insurgencies, informed by Marxist–Leninist ideology broadly understood, shaped civil wars, the main form of armed conflict since World War II (WWII). Specifically, we focus on “revolutionary socialist” (“RS”) rebels. We argue that, despite differences in doctrinal interpretation, internal organization, and/or behavior toward civilians, RS groups tended to adopt methods and practices likely to boost their battlefield performance, thus posing a powerful threat to incumbent regimes.

RS rebels launched formidable challenges against incumbent regimes powered by disciplined and cohesive organizations implementing a revolutionary war doctrine. Put differently, their transformational and transnational character raised their battlefield performance via two key attributes: an integrated political and military structure and a dense web of interactions with the civilian population. This translated into “robust insurgencies,” that is, highly demanding, long, and intense irregular wars fought against relatively strong regimes.

We empirically investigate these claims and find support for them. Additionally, we find that external assistance for RS rebels alone cannot account for these attributes and outcomes. However, and contrary to our expectations, we also find that their enhanced battlefield performance failed to translate into higher rates of success: RS rebels were no more likely to win than non-RS rebels—hence, a “Marxist Paradox.” We suggest that RS rebels represented a credible existential challenge for incumbent regimes, thus triggering a powerful counter-mobilization or, in the parlance of that era, a “counter-revolution.” We highlight the surprising state-building dimension of civil wars involving RS rebels and discuss its implications for other types of revolutionary groups, most notably Islamist rebels. Overall, our analysis reinforces recent findings about the importance of ideology in civil wars, while also linking it to the historiographic concept of world-historical time.

A MACRO-HISTORICAL APPROACH TO IDEOLOGY AND CONFLICT

While ideology as a concept was once central to the study of domestic and international politics (Aron Reference Aron1966; Haas Reference Haas2005; Mannheim Reference Mannheim1936; Schurmann Reference Schurmann1969), it became marginalized (Hanson Reference Hanson2003; Kramer Reference Kramer1999; Voeten Reference Voeten2021, 20). The study of conflict, and within it civil wars, is no exception to this trend. By focusing mainly on structural processes, such as poverty, natural resource endowment, or ethnic inequalities (Cederman, Weidmann, and Gleditsch Reference Cederman, Weidmann and Gleditsch2011; Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Wimmer, Cederman, and Min Reference Wimmer, Cederman and Min2009), the comparative study of civil wars has tended to privilege deep structures over the ideology and politics of armed actors as a critical explanatory factor. The dominant tendency is to perceive ideology as fuzzy, inchoate, opportunistic, or epiphenomenal. Nationalism, for example, is often viewed merely as an expression of ethnic grievances, and Marxism as an opportunistic window-dressing strategy for tapping foreign assistance during the Cold War. Ideologies that dominated entire historical eras and inspired millions are either seen as statistical noise to be expunged from the analysis or as proxies for other, supposedly more important, variables.

For example, rather than being conceived as a broad system of concepts and symbols that informed how political actors understood the world, the Cold War has been approached as a proxy for foreign aid to belligerents in civil wars (Lacina Reference Lacina2006, 286). At the same time, the recent “historical turn” in political science often treats the past merely as a repository of potential causal drivers of present-day political behavior (for example, see Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017). However, as the historian Tony Judt (Reference Judt2008, 15) warned, by “consigning defunct dogmas to the dustbin of history,” we run the risk of missing the importance of “the allegiances of the past—and thus the past itself.”

Recently, however, ideology is making a comeback in the study of conflict and violence—with the most compelling contributions being theoretical. Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood (Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014), Strauss (Reference Strauss2015), and Leader Maynard (Reference Leader Maynard2019) all point to the crucial ideological foundations of conflict and mass violence, and show how ideologies understood as “narratives about the world” and “visions of politics” provide shortcuts that can guide the choices and actions of armed actors.Footnote 1 However, when it comes to the empirical study of civil wars, socially transformative ideologies, as a variable worth exploring in depth, have been generally bypassed. “Sticky” ethnicity (Wucherpfennig et al. Reference Wucherpfennig, Metternich, Cederman and Gleditsch2012, 85) has typically been set up in opposition to “malleable” (and, by extension, elusive) ideology—and, as such, has attracted considerably more research attention.Footnote 2 Notable exceptions include Ugarriza and Craig (Reference Ugarriza and Craig2013), who find that Colombian rebel groups that invested in ideological development and indoctrination became more cohesive; Toft and Zhukov (Reference Toft and Zhukov2015), who compare the performance of Islamist and Nationalist groups in the Caucasus and find the former to be more resilient; Stewart (Reference Stewart2021; Reference Stewart2023), who focuses on the “revolutionary repertoires” of rebel groups and their translation into distinct structures of rebel governance, as well as the emergence of leftist leaders in colonial settings; and Basedau, Deitch, and Zellman (Reference Basedau, Deitch and Zellman2022) and Keels and Wiegand (Reference Keels and Wiegand2020), who maintain that radical ideologies act either as “morale boosters” or signals of political incompatibility.

These are valuable contributions that move the empirical agenda forward but are either too broad in measuring ideology or too specific in focusing on a few cases. Indeed, the empirical study of ideology in civil wars often oscillates between two opposite poles. On the one end, ideology is defined in very broad, transhistorical terms. Categories such as “extremism” are defined as the distance between a group’s stated goals and the political status quo (Joyce and Fortna Reference Joyce and Page Fortna2025, 156); or comparisons are made across broad categories, such as religious versus secular, and liberal versus illiberal ideologies (Basedau, Deitch, and Zellman Reference Basedau, Deitch and Zellman2022). The opposite end is characterized by a granular focus on the micro level to leverage spatial and temporal nuance—including on individual fighter motivations (for example, see Abramson and Qiu Reference Abramson and Qiu2024). While this perspective allows scholars to capture fine-grained ideological variation within related groups, and even within a single group (for example, see Hoover-Green Reference Hoover-Green2018), it risks bypassing more macroscopic variation, rejecting it as “broad typologies” (Schubiger and Zelina Reference Schubiger and Zelina2017, 950) or “panoramic” views (Thaler, Juelich, and Ashley Reference Thaler, Juelich and Ashley2024).

By adopting a macro-historical approach, we position ourselves firmly between these two poles. Unlike the first one, we historicize ideology by connecting it to “world-historical time,” that is, processes and norms associated with particular historical moments in history (Bourke and Skinner Reference Bourke and Skinner2023; Koselleck Reference Koselleck2004). Specifically, we focus on a key actor, the RS rebels that dominated a particular historical era, the Cold War—a type that has been used in recent comparative research in various formulations (Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Balcells, Chen, and Pischedda Reference Balcells, Chen and Pischedda2022; Kreiman Reference Kreiman2025; Staniland Reference Staniland2021; Stewart Reference Stewart2021; Reference Stewart2023). RS rebels constitute a subtype of the broader category of “revolutionary” rebels, who seek to overthrow the existing social order and replace it with a new one, rather than merely winning power or setting up a new state (Stewart Reference Stewart2021). While the precise content of the Marxist worldview varied, RS rebels upheld a political project built around a single-party state and an economic organization based on a central command economy with limitations on the private property of the means of production.

The Cold War, roughly between 1945 and 1991, when global conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union dominated international affairs, “cannot be understood without acknowledging that the major players had fundamentally different views on how domestic and international societies should be organized” (Voeten Reference Voeten2021, 22–3). During that time, revolutionary rebels were almost exclusively broadly Marxist in orientation. In focusing on RS rebels as a key category, we draw inspiration from the study of political parties, which has long relied on the concept of “party families,” such as Social Democrats, Communists, Christian Democrats, Liberals, and so forth. This approach classifies parties across different countries based on shared ideologies that tend to capture cleavage dimensions, policy goals, historical origins, and organizational characteristics, despite variation across countries and over time (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Sartori Reference Sartori1976).

We understand ideology to be a broad worldview, “a more or less systematic set of ideas that includes the identification of a referent group, an enunciation of grievances faced by that group, the identification of objectives on its behalf, and a program of action (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014, 215). RS rebels were all inspired by some version of Marxism, although they interpreted Marxist ideology in a variety of ways: there were Marxist–Leninists, Communists, Maoists, and many other variants. One could fill libraries (and they were indeed filled) with the esoteric ideological debates and sectarian doctrinal disputes animating these groups. Local conditions added complexity by prompting varying practices: for example, despite similar Maoist outlooks, the Naxalites in India and the Shining Path in Peru adopted different methods of combatant socialization (Hirschel-Burns Reference Hirschel-Burns2021). Likewise, organizational choices, strategic priorities, and the use of violence exhibited fluidity and varied at the micro level.Footnote 3

We concur with Hirschel-Burns (Reference Hirschel-Burns2021), Moro (Reference Moro2017), and Schubiger and Zelina (Reference Schubiger and Zelina2017) that groups with similar programmatic allegiances might also exhibit differences. However, we contend that considered from a macro-historical perspective, these groups also share key ideological features, organizational cultures, and political and military practices. Despite permutations, we argue that RS rebels can be gainfully analyzed as an identifiable type in the macro-historical world of civil conflict, very much like communist parties can be analyzed as of the same type, despite considerable variation between them (e.g., Tucker Reference Tucker1967).

As an example, consider, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), two of the largest RS groups in Colombia. Both groups engaged in a multiyear war against the Colombian government. Founded in 1964, the ELN was inspired by the Cuban Revolution and was considered more ideological and dogmatic than the FARC, stressing its commitment to Marxist principles and revolutionary struggle. The FARC, which emerged from a communist-inspired peasant movement, was similarly influenced by Marxist–Leninism but was more flexible in its practices, engaging for instance, in extensive drug trade (Jonsson Reference Jonsson2014). Despite differences in strategic choices, doctrines, and organizational culture, they can both be described as RS groups that engaged in long-lasting, bloody, and robust insurgencies against the same powerful foe, the Colombian state (Medina Gallego Reference Carlos2010). They both built disciplined and cohesive organizations combining political and military wings; they both engaged in extensive mobilization, indoctrination, and governance of civilians; and they both established a notable international presence (Medina Gallego Reference Carlos2010; Ugarriza and Craig Reference Ugarriza and Craig2013). In other words, they can be treated as “of a single species” from a macro-historical perspective: their differences pale when compared to another key actor of the Colombian conflict, the rightwing paramilitaries.

In an essentially bipolar world, and despite differences and occasional infighting, RS rebels saw themselves as broadly on the same side of history, namely as leftist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist actors. Indeed, competing RS factions were more likely to form alliances with each other than any other group dyad, including those sharing the same ethnic constituency (Balcells, Chen, and Pischedda Reference Balcells, Chen and Pischedda2022, 12). Their rivals also perceived them as of one kind. The United States, for example, saw the Palestinian Liberation Organization as not merely a Middle Eastern nationalist group, but as an organization that “came to embody the threat of transnational radicalism everywhere” (Chamberlin Reference Chamberlin2012, 93).

It might be also tempting to dismiss Marxism as mere window-dressing, cheap talk adopted to gain access to Soviet bloc resources. Yet, even the eventual decline of an ideology does not imply that it was adopted and pursued opportunistically. In addition, the fact that some RS groups ultimately shed their Marxist ideology should not be taken to mean that it was a sham all along.Footnote 4 The founders and leaders of these movements were often intellectuals who adopted a version of Marxism long before launching an insurgency (Gott Reference Gott2007; Reno Reference Reno2011); the importance of their ideological vision was well understood by their rivals who studied them and attempted to counter them. Indeed, counterinsurgency began as a counterrevolutionary doctrine (Leites and Wolf Reference Leites and Wolf1970; Trinquier Reference Trinquier1964). Moreover, most RS rebels who successfully overthrew incumbent regimes implemented transformational policies and established their own socialist regimes, following their ideological precepts (Ballesteros, Balcells, and Solomon Reference Ballesteros, Balcells and Solomon2021; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2022), while also continuing to rely on techniques honed during the conflict, most notably party-led mass mobilization (Javed Reference Javed2022, 202; Looney Reference Looney2021). Rather than seeing ideology as epiphenomenal to international politics, historians of the Cold War approach it as a product of ideological rivalry: Cold War conflicts were fought “with the ferocity that only civil war can bring forth” because they were often extensions of ideological civil wars, points out Westad (Reference Westad2005, 5).Footnote 5

HOW IDEOLOGY MADE A DIFFERENCE

Locked in conflict over the very concept of modernity—to which both regarded themselves as the one true expression—Washington and Moscow sought to change the world in order to prove the universal applicability of their ideologies and sociopolitical systems. Newly independent states proved a fertile ground for their competition. Hence, superpower interventions in civil wars were not merely instances of foreign meddling but also deeply rooted local manifestations of a global ideological struggle (Westad Reference Westad2005, 4–5). RS rebel groups represented the Marxist worldview; they were a staple of the Cold War: rare before WWII, they have almost disappeared since.

It is not uncommon to see ideology as epiphenomenal to other, more important variables; ironically, Marxism has been highly influential in shaping this view, as it posits the causal primacy of material over ideational forces (Cohen Reference Cohen1979). The adoption of an RS outlook was often accompanied by political and military support from the Soviet Union and/or China and their allies, particularly Cuba. At the same time, as we discuss below, many RS groups operated with limited or no foreign assistance.

RS rebels share many attributes with other kinds of rebels; what distinguishes them is the specific combination of these attributes and their implementation. Here is how. First, disciplined and cohesive rebel organizations grew out of a highly institutionalized, integrated political and military structure. RS rebels were never simple military organizations; they were instead armies run by parties. Political aims were central to the recruitment and discipline of rebel fighters (Reno Reference Reno2011, 38), and well-trained political cadres ran both political and military arms in a bureaucratically coordinated way. Typically, unit command structures featured both a military commander and a political commissar (Connell Reference Connell2001, 354; Mazower Reference Mazower2001). Roessler and Verhoeven (Reference Roessler and Verhoeven2016, 9) note that some of the strongest politico-military organizations in Africa were explicitly modeled on these structures and principles, while Karabatak (Reference Karabatak2020) finds that delegating nonmilitary tasks to the political rather than the military wing, a practice closely associated with RS rebels, strengthened insurgent command and control, and decisively boosted their performance.

Second, RS rebels were able to build a dense web of interactions with the civilian population via a combination of mobilization and indoctrination, public goods provision, and the use of selective violence. RS rebels mobilized the masses via “front” organizations, privileged women for combatant recruitment (Wood and Thomas Reference Wood and Thomas2017), and invested considerable resources to indoctrinate both their combatants and civilians living under their control (Hoover-Green Reference Hoover-Green2018). Indoctrination created a strong (and measurable) bond between these groups and their combatants, leading to higher levels of military effectiveness (Ugarriza and Craig Reference Ugarriza and Craig2013). Further, mobilization was enhanced by the implementation of extensive and intensive structures of local governance (Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Stewart Reference Stewart2021). RS rebels designed and implemented a host of often sophisticated public policies targeting the populations they ruled, from literacy programs (Huang Reference Huang2016, 109) to the training of health workers (Devkota and van Teijlingen Reference Devkota and van Teijlingen2010). These policies tightened the bonds between rebels and civilians, generating significant material and nonmaterial resources for the rebels, including voluntary recruitment, political support, and shared information. They also served to demonstrate to outsiders the group’s credible capacity to control territory and administer populations (Reno Reference Reno2011, 40), while also helping them to sanction fence-sitters and potential defectors (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006).

Overall, RS rebels were ideally suited to launch and sustain “robust insurgencies,” that is, insurgencies that were likely to last longer, be fought more intensely (producing more battle-related deaths), and represent a greater threat to existing regimes compared to other rebels. To understand why we turn to the drivers of battlefield effectiveness.

Summarizing a vast and often confusing literature about state militaries engaged in conventional wars, Lyall (Reference Lyall2020, 8–9) highlights two broad factors driving military effectiveness: military power and organizational cohesion.Footnote 6 Most rebel groups begin from a position of extreme weakness vis-à-vis the state: their military power is far inferior compared to that of the regimes they seek to overthrow. Insurgency, guerrilla, or irregular war is a method of warfare where “rebels have the military capacity to challenge and harass the state but lack the capacity to confront it in a direct and frontal way” (Kalyvas and Balcells Reference Kalyvas and Balcells2010, 418–9). This type of warfare helps rebels compensate for their weakness, trading brute military power for tactical flexibility requiring organizational cohesion. To do so, they must build a highly disciplined organization with an effective command-and-control structure and rely on the civilian population (Galula Reference Galula1964; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Leites and Wolf Reference Leites and Wolf1970; Wickham-Crowley Reference Wickham-Crowley1991). Among the many rebel groups that engage in irregular war, relatively few succeed in fully developing those attributes and becoming “integrated groups” (Kreiman Reference Kreiman2025; Staniland Reference Staniland2014). The RS rebels of the Cold War era were among the most successful rebels in achieving that goal. They were ideally suited to insurgency as a method of warfare because they enjoyed a comparative advantage vis-à-vis other rebels: they developed and deployed a war doctrine whose adoption and effective execution hinged on the fact that they were both transformational and transnational actors.

Revolutionary War Doctrine

Although guerrilla warfare is a very old military tactic, it evolved as states grew stronger and more effective.Footnote 7 Before the WWII, guerrilla warfare consisted mainly of indigenous resistance against imperial or colonial encroachment. Such resistance tended to take the form of a lopsided clash between vastly unequal armies, leading to crushing victories for imperial and colonial forces (Lyall and Wilson Reference Lyall and Wilson2009). Whereas traditional guerrilla wars were based on the mobilization of primarily conservative, parochial grievances activated by local patronage, tribal, and kin networks, described by Staniland (Reference Staniland2014) as “parochial mobilization,” RS rebels took over the leadership of rural populations by infusing existing grievances with a newfound and resolutely modern revolutionary spirit: they did not just mobilize peasants but actively sought to turn them into revolutionary actors through indoctrination, social transformation policies (for example, land reform), and new governance structures. In short, the “spirit” of traditional peasant rebellion was harnessed by the ideology and organization of modern revolution and the doctrine of revolutionary war (Desai and Eckstein Reference Desai and Eckstein1990, 442).

Here is this doctrine in a nutshell: revolution can be achieved via armed insurgency in the countryside rather than either nonviolent action or urban uprising. Insurgency gave subordinate or weak actors the best possible shot at overpowering powerful states. Examples of high-profile, successful, and celebrated insurgencies against German and Japanese occupations during WWII (most prominently in Yugoslavia and China), and later in Cuba, Algeria, and Vietnam, confirmed in the minds of revolutionary activists around the world that, despite occasional setbacks, guerrilla warfare, if correctly waged, was both a feasible and successful path to political and social change, indeed the most likely one. This template, a doctrine initially codified by Mao Zedong during the 1930s in China, turned into a particular form of waging war known as “people’s war,” “revolutionary war” (Trinquier Reference Trinquier1964), revolutionary guerrilla warfare, or “robust insurgency” (Kalyvas and Balcells Reference Kalyvas and Balcells2010). Unlike Marx and Engels who emphasized the mobilization of the urban working class rather than military action and who saw guerrilla war as likely to degenerate into banditry or “praetorianism” (Pomeroy Reference Pomeroy1968, 14), and unlike Lenin who saw revolution as an urban-based military action led by a proletarian vanguard and who thought of peasant rebellions as reckless, undisciplined, and chaotic (Pomeroy Reference Pomeroy1968, 19), Mao’s revolutionary doctrine rested on mass peasant mobilization and “protracted people’s war” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1996; Schram Reference Schram1963; Schurmann Reference Schurmann1969). Various versions of this doctrine were put into practice by communist resistance movements in Europe and Asia during WWII. Eventually, it reached its apex during the Cold War throughout the developing world. According to Hobsbawm (Reference Hobsbawm1996, 438), this was an invention whose global breakthrough was amplified by the success of the Cuban Revolution, “which put the guerrilla strategy on the world’s front pages.”

Mao’s original doctrine, often infused with a national resistance spirit, was further refined and elaborated by “theorist–practitioners” such as Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Régis Debray, and Amilcar Cabral, among many others. Their writings were widely disseminated to thousands of activists and sympathizers across the world, particularly the university-educated youth. There was plenty of heated debate about what the best model of revolutionary action was, ranging from Mao’s original doctrine (positing a transition from guerrilla to conventional warfare) to “foquismo” (the voluntaristic, vanguard action by small armed groups that would focalize mass participation, advocated by Che Guevara), to Carlos Marighella’s urban warfare—and many others. However, particularly after the failure of political experiments involving both the “foquist” and urban insurgency approaches, RS’s revolutionary war doctrine congealed around the model of a robust, peasant-based guerrilla war (Kreiman Reference Kreiman2025).

Counterinsurgency theorists fully understood that, although sharing the same moniker as traditional guerrilla war, this was a “revolutionary war” of a completely new kind (Galula Reference Galula1964; Leites and Wolf Reference Leites and Wolf1970; Trinquier Reference Trinquier1964). It was never a matter of simple military tactics, akin to insurgent “special forces” storming their way to power, but a deeply political process. Rebels learned that the key to success lay in the patient formation of a highly structured political organization, a party fully in control of a centralized, disciplined, and politically indoctrinated army. Its objective was to acquire (“liberate”) and govern territory, usually located in the country’s periphery, and develop comprehensive political institutions that acted both as mobilization tools and a demonstration of superior political capability. This amounted to revolutionary state-building (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006), which was either absent or limited in traditional guerrilla warfare (Stewart Reference Stewart2021, 13).Footnote 8 Although the revolutionary war doctrine was widely disseminated and could be adopted by nonrevolutionary rebels, it was fully and effectively deployed primarily by RS rebels, for a key reason: they were both transformational and transnational actors. Non-RS rebels were often keen to emulate the revolutionary war doctrine (and a few managed to), but their lack of either a transformational or a transnational dimension proved crucial.

Transformational and Transnational Actors

A popular perspective posits that ideology operates mainly at the individual level, and its impact is emotional and motivational: fighting for a “just cause” is likely to increase hostility toward ideological enemies and generate a willingness to fight harder, accept greater moral sacrifice, and compromise less (Basedau, Deitch, and Zellman Reference Basedau, Deitch and Zellman2022; Walter Reference Walter2017). At the dyadic level, the presence of revolutionary goals might aggravate hostility and distrust, and heighten the commitment problem between rivals, thus prompting a more intense response from the regime in place (Keels and Wiegand Reference Keels and Wiegand2020). Although true for RS rebels, their ideological commitment went much deeper: it structured their thinking and acting, and it shaped their entire existence.

RS rebels were “transformational” actors (Stewart Reference Stewart2021, 262). They sought to overturn the social and political order and restructure existing social hierarchies (Tilly Reference Tilly1993, 6). They took on well-entrenched elites and implemented—often costly—land redistribution policies; they advocated for gender egalitarianism and promoted policies reducing discrimination against women; indeed, they recruited the highest number of female fighters (Wood and Thomas Reference Wood and Thomas2017, 43–4). Often, they merged revolutionary ideas with nationalist goals in the context of nationalist self-determination and/or anticolonial movements (Voller Reference Voller2022), but also championed an anti-imperialist discourse that stressed national sovereignty and condemned foreign interference. For example, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka, initially a Marxist–Leninist group (Balasingham Reference Balasingham1983), applied the RS war doctrine, stressing mass indoctrination and mobilization, the recruitment of women, and revolutionary state-building (Stokke Reference Stokke2006). Marx and Lenin had condoned the reliance on national aspirations as a means of furthering the world revolutionary movement (Connor Reference Connor1984) and Marxism–Leninism held great appeal for rebels in the postcolonial world by combining the nation-state idea with the struggle against oppression (Reno Reference Reno2011, 26). The combination of Marxism, anticolonialism, and the right to self-determination boosted the revolutionary and progressive credentials of RS movements in the developing world (Getachew Reference Getachew2019). Through repetition, imitation, diffusion, or emulation, robust insurgency came to be, to paraphrase Stewart (Reference Stewart2021, 263), “the expected, appropriate, and correct behavior for rebels with more transformative goals.” The example of successful revolutionary insurgencies reinforced the belief that revolution was not a pipe dream, but a realistic prospect within tantalizing reach.

The revolutionary war doctrine was developed, updated, and refined within a transnational movement—a feature lacking for nonrevolutionary rebels. Ideology provided the glue that kept revolutionary activists from around the world together, united around a common project.Footnote 9 This transnational dimension brought three key benefits to RS rebels.

First, it imparted and consolidated a shared belief in a credible counter-hegemonic understanding of the world. Rather than having to nurture a political project in isolation, RS rebels participated in a global movement that reinforced their belief that they were building a new world. It also provided a key source of motivation for crucial “first movers” who accepted tremendous risk in the name of revolution, while also operating as a selection process, helping to weed out opportunists and adventurers. RS activists and sympathizers met and interacted regularly with each other, training in a variety of locales. Cuban training camps, for example, welcomed activists from all over Latin America, while Palestinian camps in Lebanon trained activists from Europe, Africa, and Asia (Marcus Reference Marcus2007). Algiers, Cairo, Damascus, Bagdad, Havana, and Dar Es Salaam became known as “revolutionary cities,” serving as hubs for activists planning insurgencies, and earning labels like “Meccas for Revolutions” or “epicenters of Third World Revolution” (Byrne Reference Byrne2015; Marchesi Reference Marchesi2018; Roberts Reference Roberts2021).

Second, the transnational dimension spread the know-how of a detailed but also adaptable and constantly updated blueprint of armed political and social struggle, thus facilitating a process of “revolutionary mimesis” (Stewart Reference Stewart2021, 278) and encouraging creative mixes of local knowledge with standard practices. For example, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was able to develop an effective technique of attack, known as qoretta, “a combination of the traditional Ethiopian mode of envelopment and Chinese and Vietnamese tactics of annihilation” (Tareke Reference Tareke2009, 93).

Third, it helped RS rebels internationalize their cause, including but not limited to diplomatic representation and international solidarity networks. By publicizing their activities internationally, RS rebels could claim moral and material support from international sympathizers as well as from the Soviet Union and its allies, including weapons, training, access to military advisers, and civilian aid (Chamberlin Reference Chamberlin2012; Huang Reference Huang2016). It also helped generate international pressure against the regimes they challenged (Wood Reference Wood2000).

Reliance on this transnational movement clearly distinguishes RS rebels from both parochial insurgents and their postmodern predatory and “greedy” counterparts—the Che Guevaras and Abdullah Öcalans from the Charles Taylors and Foday Sankohs. Consider Yoweri Museveni, a rebel leader who went on to rule Uganda and whose “biography personifies the evolution of the liberation struggle in Africa over the past fifty years” (Roessler and Verhoeven Reference Roessler and Verhoeven2016, 408). He attended the University of Dar es Salaam in the late 1960s, where he studied with the Marxist and Pan-Africanist thinker Walter Rodney. At the time, Dar es Salaam was teeming with revolutionary energy: “The excitement at the revolutionary possibilities was palpable. Nkrumah Street and its environs in Dar Es Salaam became the heartbeat of revolutionary Africa with buildings emblazoned with an alphabet soup of signs, such as ANC, PAC, SWAPO, ZANU, ZAPU or FRELIMO” (Roberts Reference Roberts2021, 1–2).Footnote 10 Museweni voraciously read and debated the works of Franz Fanon and interacted with fellow budding revolutionaries in a student group he helped found, the University Students’ African Revolutionary Front (USARF). The group included John Garang, future head of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement, and Eriya Kategaya, the future number two of Museveni’s rebel movement, NRA/M. The members of USARF identified closely with the Mozambican liberation movement, FRELIMO, which was founded in Dar es Salaam in 1962 and maintained its headquarters there. In 1968, Museveni and other members of USARF traveled to FRELIMO’s liberated zones in Northern Mozambique, to learn the nuts and bolts of revolutionary insurgency. Upon his return to Dar es Salaam, Museveni wrote a thesis applying Fanon’s theory of revolutionary violence to the case of FRELIMO and Mozambique.

The revolutionary war doctrine of RS rebels was not a secret recipe: it was publicized and non-RS rebels, mainly secessionists, did try to imitate it, sometimes with a measure of success. Examples include the UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi in Angola and the Mujahedin leader Ahmad Shah Massoud in Afghanistan. Some, like Savimbi, were initially RS militants (Gleijeses Reference Gleijeses2002), while others, like Massoud, studied the experience and practice of RS rebels (Roy Reference Roy2011). Nevertheless, executing this doctrine was extremely hard absent the transformational and transnational dimension of RS rebels. Revolutionary goals produced motivation, inspiration, and a feeling of belonging to the “vanguard of history,” which also acted as selection mechanism for recruitment, while transnational interactions infused the shared organizational culture of the RS movement with the accumulated knowledge of past successes and failures, helping turn it into a credible armed challenge.

EMPIRICS

Our argument produces several expectations about the impact of RS ideology on civil wars. First, we expect RS rebels to be more likely than other rebels to fight irregular wars. Fighting such wars is exacting because it entails a capacity to field a cohesive and resilient army able to withstand the pressure of a stronger enemy and to hide among the civilian population whose collaboration is necessary (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006). Moreover, and relatedly, we expect RS rebels to be more likely than other rebels to fight “robust insurgencies,” that is, insurgencies lasting longer and fought more intensely. Longevity, coupled with intensity, signals superior battlefield capacity and organizational competence. Lastly, we also expect RS rebels to be more successful compared to other rebels. Although war outcomes are a function of many factors (Lyall and Wilson Reference Lyall and Wilson2009), we expect superior capacity to translate into successful outcomes and, hence, RS rebels to be, on average, more likely to generate victories.

To empirically assess our theoretical analysis, we triangulate qualitative and quantitative evidence. We begin by drawing from the historical and comparative literature to support our assertion that RS groups possessed the highlighted attributes, which were associated with the described effects. We then offer quantitative evidence linking those attributes with several dimensions of civil wars between 1944 and 2016, interspersed with qualitative comparisons that address questions generated by our findings.

Qualitative Evidence

We begin by noting that students of social revolution (which includes revolutionary civil wars) have pointed to a link between successful revolutionaries’ organizational capacity and regime durability (Tilly Reference Tilly1993). More recently, Clarke (Reference Clarke2023), Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2022), Meng and Paine (Reference Meng and Paine2022), and Lachapelle et al. (Reference Lachapelle, Levitsky, Way and Casey2020) have linked the durability and resilience of revolutionary regimes (compared to all other autocratic regimes) with the characteristics of the organizations that fought revolutionary wars and won. As Lachapelle et al. (Reference Lachapelle, Levitsky, Way and Casey2020) document, autocracies emerging out of violent social revolutions were able to develop cohesive ruling parties and powerful and loyal security apparatuses, leading to unusually long-lasting regimes. This finding highlights the significance of the organizational capacity of RS rebels. Another way to assess whether RS rebels were better performing on average than non-RS rebels is to look at the few instances when RS and non-RS rebels competed against each other in the same historical and political context. Three cases stand out: WWII Yugoslavia and Greece, and Eritrea. In all three cases, RS rebels proved superior compared to their non-RS competitors.

Milovan Djilas, a prominent associate of Yugoslav communist leader Josip Broz Tito (and later his critic), discusses, in his 1977 first-hand account of the conflict, the success of the Communist Partisans over the Nationalist Chetnik rebels during WWII. He highlights the Partisans’ ideological cohesion and discipline and their adoption of a clear ideological framework, which translated into an effective military strategy, supported by an extensive investment in peasant mobilization and governance. Foreign assistance was not a key factor, at least not before the Partisans emerged as the strongest movement, because the British initially supported both groups (Djilas Reference Djilas1977; Dulić and Kostić Reference Dulić and Kostić2010; Tomasevich Reference Tomasevich2001). Likewise, in Greece, during the same period, the British supported both the communist National Liberation Front (EAM) and the non-communist National Republican Greek League (EDES), but the former quickly outgrew and eventually marginalized the latter. Unlike EDES, which relied on local networks, EAM built its own political network across the country and developed both a hierarchical command structure and a disciplined fighting force. Tightly controlled by the Communist Party, EAM crafted extensive governance structures, mobilizing and indoctrinating civilians, particularly women and youth (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas, Ana, Kasfir and Mampilly2015; Mazower Reference Mazower2001). Eritrea offers a similar example, albeit in a different continent and time (Stewart Reference Stewart2023). The RS Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) proved far more successful than its competitor, the moderate Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), thanks to its organizational cohesion and disciplined action. In the mid-1970s, both the ELF and the EPLF posed a similarly serious military challenge to the Ethiopian regime with comparable military forces and no foreign backers. Their key difference was their revolutionary character. Unlike the ELF, the EPLF built extensive governance institutions and launched a land reform program. It dismantled existing village administrations and replaced them with local committees to handle tasks like security, judiciary affairs, health care, forestry, and mining. In larger towns, the EPLF apparatus controlled the judicial process, issued identity cards, administered house rents and prices, controlled trade exchanges between liberated areas and those under state authority, changed pay scales for workers, and ran mass political education and literacy classes (Pool Reference Pool2001, 120–6). Its organization became legendary because of its centralized command and control system, highly disciplined army, and ability to mobilize the civilian population, particularly women (Pateman Reference Pateman1998). After the two groups turned against each other, the EPLF won and drove the ELF out of Eritrea.

In a slightly different comparison, Suykens (Reference Suykens, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015) contrasts an RS group (the revolutionary Naxalites) with a non-RS, secessionist group (the Naga nationalists) in different Indian states. He asks how different rebel goals impacted practices of rebel governance, reporting profound differences between the two. The Naxalites assumed they would have to work hard to convince skeptical civilians to join them and invested in mobilization, indoctrination, and governance, while the Naga insurgents neglected these crucial steps.

Obviously, not all RS groups that took up arms survived to fight robust insurgencies. In fact, most failed, underscoring the enormous difficulty of this undertaking. Kreiman’s (Reference Kreiman2025) analysis of all Latin American RS armed groups between 1950 and 2016 shows that two key variables that explain rebel transition from low to high capacity are consistent with those that differentiate RS and non-RS groups: their ability to internationalize their cause and the presence of a political wing.Footnote 11

Quantitative Evidence

We now turn to a dataset of 178 civil wars, covering the 1944–2016 period, to investigate the effect RS rebels had on four conflict dimensions: technology of rebellion (TR), duration, severity, and outcome of the wars in which they participated.Footnote 12 We code all civil wars based on the ideology adopted by the main rebel organization, thus producing two groups: the first consists of civil wars dominated by RS rebels, where the main rebel group professed an RS ideology at the outset of the war (when they produced a political manifesto or made public declarations that had references to Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, or a Socialist revolution). The second group consisted of all civil wars where the main rebel group was not RS.Footnote 13 A total of 41 wars in our dataset (23% of the total) were dominated by RS rebels, while 137 wars (77%) were fought by non-RS groups.

Our main analyses distinguish “RS civil wars” from “non-RS civil wars.” To add nuance, we also create a fourfold distinction, which we use in additional analyses: first, civil wars dominated by RS rebels minus Marxist National Liberation (MNL) rebels, those combining a Marxist ideological profile with a secessionist agenda; second, Secessionist rebels, that is, civil wars where the main rebel group professed a secessionist agenda without adhering to an RS ideology; third, MNL, coded as the intersection of RS and Secessionist; and fourth, the residual (Others), civil wars where the main rebel organization was both non-secessionist and non-Marxist.Footnote 14 Although most RS wars in our dataset are non-secessionist (70%), a substantial minority (30%) are. It is noteworthy that most MNL groups emerged during the Cold War, which advocates against a rigid distinction between “ideological” and “secessionist” rebels.

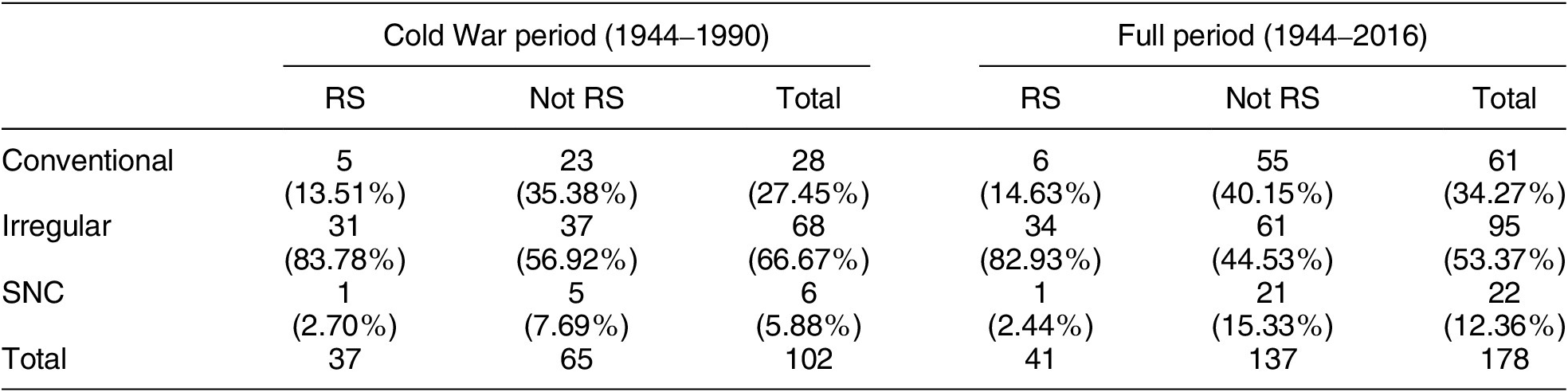

Table 1 shows the relationship between RS rebels and their TR. Kalyvas and Balcells (Reference Kalyvas and Balcells2010) distinguish between three TR categories: irregular or guerrilla war, conventional war, and symmetric nonconventional war. Based on our theoretical discussion, we expect RS rebels to display a comparative advantage in launching and sustaining irregular wars. Table 1 shows that civil wars with RS rebels are strikingly concentrated in the irregular war category—during both the entire 1944–2016 period and the Cold War period only (1944–1990).

Table 1. RS Rebels and Technologies of Rebellion

Note: Column percentages in parentheses.

Table 2 displays the relationship between TR and rebel types for the entire 1944–2016 period using the four-categorical variable. The notable finding here is that MNL rebels resemble their RS peers more than they resemble other secessionists. Both RS and MNL rebels fought irregular wars at similar rates, over 80% of the time, whereas the other secessionist rebels fought irregular wars 61% of the time. This affinity between RS and MNL groups confirms our perception of MNL groups as RS groups that also sought secession rather than nationalist groups pretending to be Marxist.

Table 2. Types of Rebels and Technologies of Rebellion (1944–2016)

Note: Column percentages in parentheses.

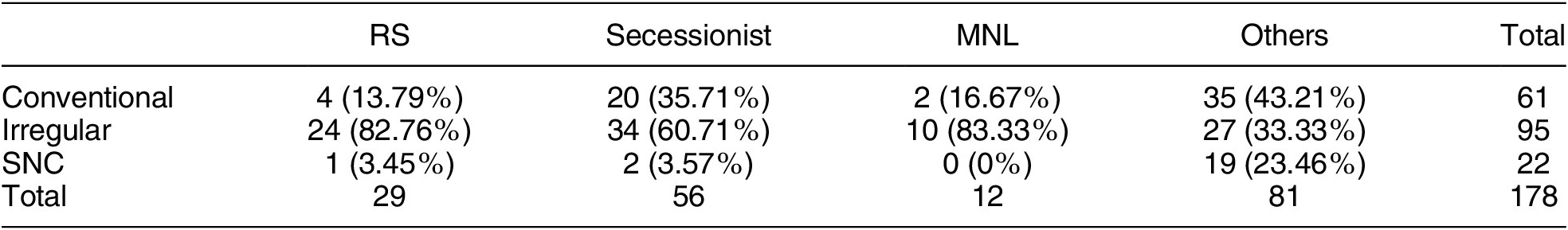

The temporal patterns in our data (Figure 1 and Figure A.3 of the Supplementary Material [SM]) are also consistent with the historical record. We know that RS rebellions (which include here MNL rebels) are closely associated with the Cold War, especially its last phase, the 1970s and 1980s, a time when nuclear détente coincided with the escalation of proxy wars in the periphery (Westad Reference Westad2005, 4). In terms of their geographical presence, these rebels were present across all continents (see Tables A.4 and A.5, Figure A.1, and Map A.1 of the SM).Footnote 15

Figure 1. RS Rebels: Temporal Patterns

Duration

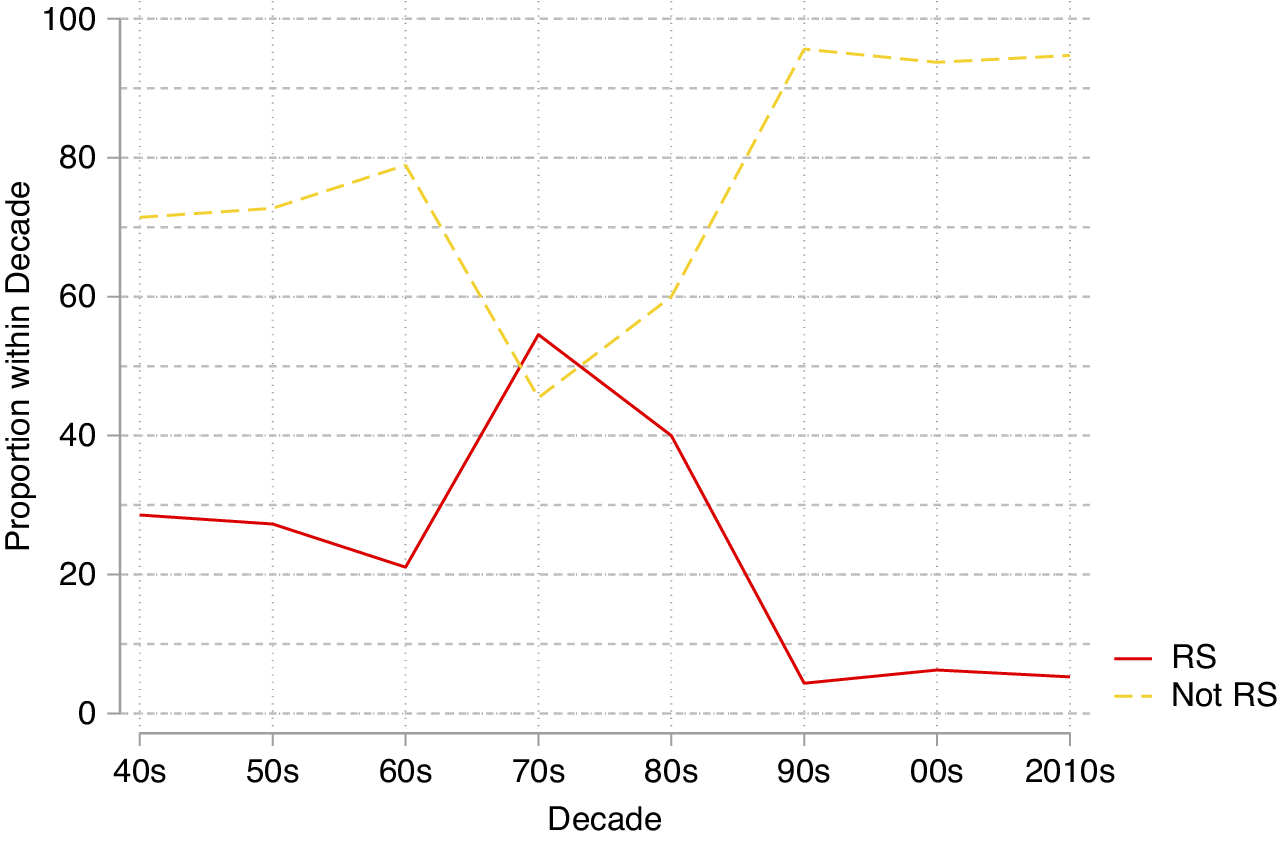

Our data suggest that civil wars featuring RS rebels lasted longer, on average, than others, consistent with our expectations. Figure 2 depicts the Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of each type of civil war, distinguishing RSs from non-RSs (again, RSs include MNL rebels; see Figure A.4 of the SM for the four-category disaggregation).

Figure 2. Civil War Duration: Kaplan–Meier Estimates by RS Rebels

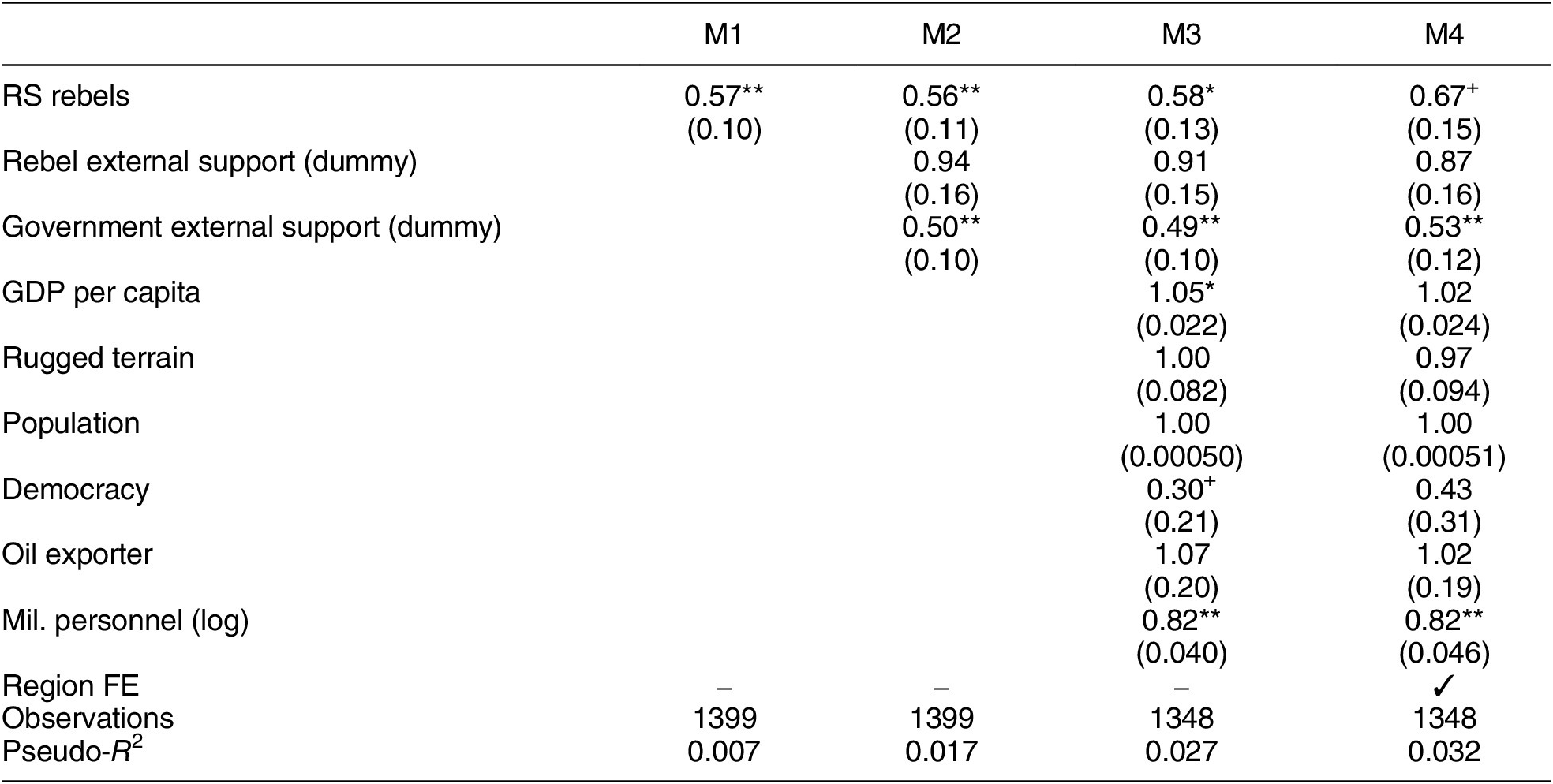

This longer duration is unsurprising, as irregular wars were the most protracted conflicts; yet, even among them, civil wars with RS rebels lasted the longest (see Figure A.5 of the SM). To more rigorously assess the effect of RS rebels on civil war duration, Table 3 presents the results of semiparametric Cox proportional hazard models; Cox proportional hazard ratios above 1 indicate a shorter duration of civil wars with an increase of one unit in the relevant covariate, while ratios below 1 indicate a longer duration. The first model (M1) is bivariate; the second model (M2) includes only external support (for rebels and states), a key variable in previous models of civil war duration (see, for instance, Schulhofer-Wohl Reference Schulhofer-Wohl2020); the third model (M3) adds several of the covariates included in Balcells and Kalyvas’s (Reference Balcells and Kalyvas2014) study on civil war duration, with the exception of TR, which, as we have just seen, highly correlates with RS. The fourth model (M4) adds regional dummies to M3.Footnote 16 The results depicted in Table 3 support the hypothesis that civil wars dominated by RS rebels tend to last longer than wars dominated by other types of rebels. We obtain similar results when using the four-categorical rebel type variable as an independent variable (Supplementary Table B.1 of the SM); both MNL and RS rebels are associated with longer wars.Footnote 17

Table 3. Cox Regressions on Civil War Duration

Note: Exponentiated coefficients; all models report robust clustered standard errors by conflict (in parentheses). GDP per capita and Population are in thousands. +

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

.

$ p<0.01 $

.

Conflict Severity

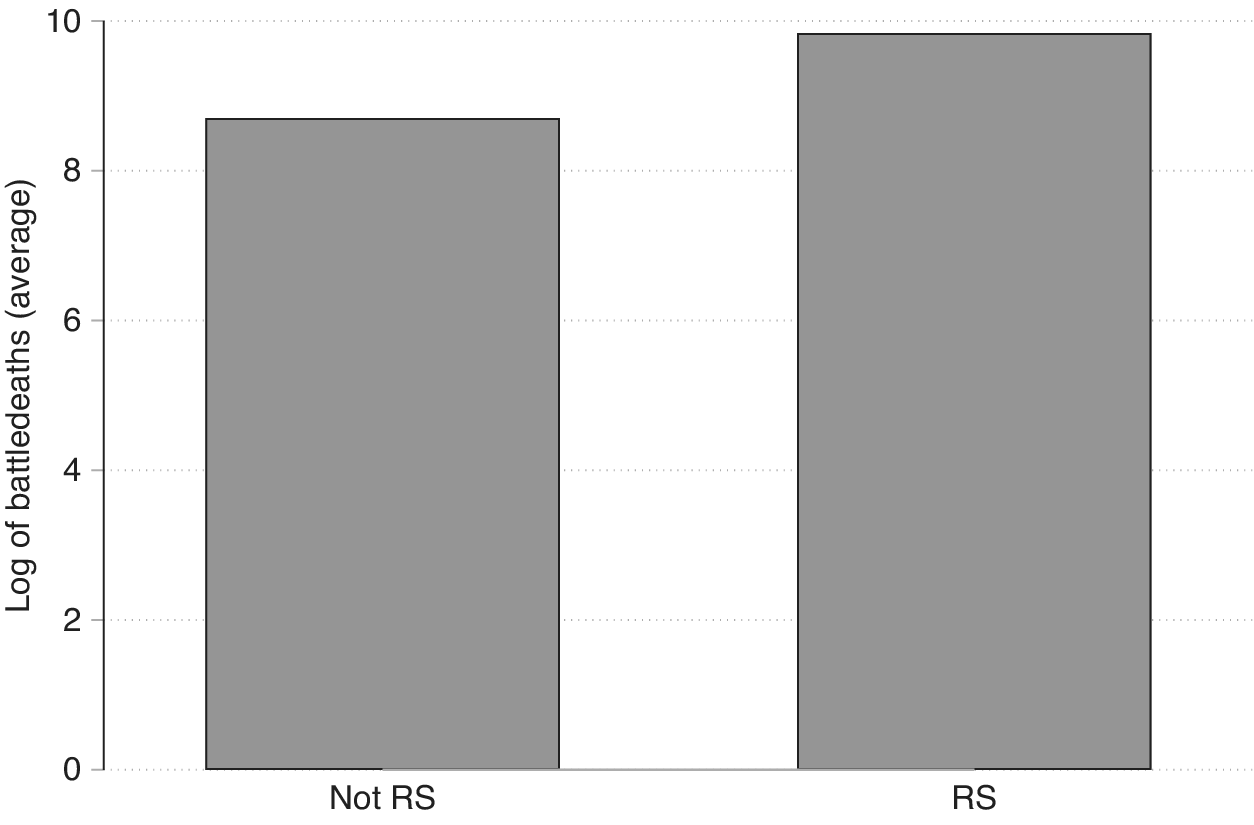

Descriptive data on battle-related deaths (Lacina and Gleditsch Reference Lacina and Gleditsch2005) show that RS civil wars are, on average, more lethal than all other civil wars (Figure 3). As with duration, this is true across both the irregular and conventional TR categories (see Figure A.6 in the SM).

Figure 3. Log of Battle-Related Deaths, by RS Rebels

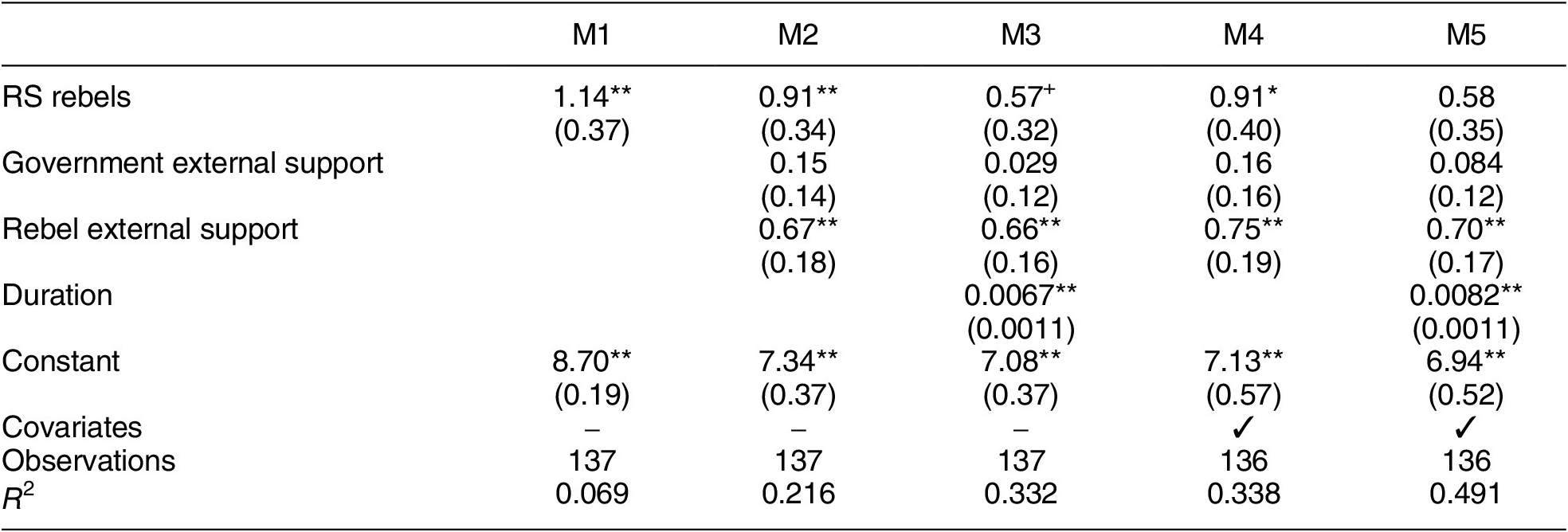

For a more rigorous assessment we regress, using a linear model, RS rebels on the total number of battle-related deaths (logged); the results are depicted in Table 4.Footnote 18 The first model shows the bivariate coefficient. M2 controls for rebel and government external support, which could have an impact on warfare dynamics. In M3, we add civil war duration (in months), which is a strong correlate of lethality and decreases the substantive effect and statistical significance of the RS dummy—although the latter retains significance at the 10% level. M4 and M5 add additional covariates,Footnote 19 which we borrow from previous works also examining the determinants of battle-related deaths (for example, see Balcells and Kalyvas Reference Balcells and Kalyvas2014; Lacina Reference Lacina2006)—including regional dummies.Footnote 20 While RS loses statistical significance in the last model, which includes all the additional covariates along with civil war duration, the results broadly support the idea that civil wars involving RS rebels tend to be more severe on the battlefield.Footnote 21

Table 4. OLS on Civil War Severity

Note: All models report robust clustered standard errors by conflict (in parentheses). Covariates in M4 and M5 include GDP per capita, Population, Oil exporter, Ethnic fractionalization, New state, Democracy index, Military personnel, and Region dummies. +

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

.

$ p<0.01 $

.

To further assess the robustness of the empirical findings on the battlefield effectiveness of RS rebels, we conduct a factor analysis to capture the shared variation between conflict severity and conflict duration, creating a composite dependent variable reflecting both dimensions. We then use the factor scores derived from this analysis as the dependent variable in replication models of Table 4 (removing duration from the right-hand side). The linear regression results, depicted in Table B.8 of the SM, are consistent with the findings above, as they show that RS rebels are associated with higher levels of this composite measure, hence indicating their involvement in conflicts that tended to be both longer and deadlier.

War Outcome

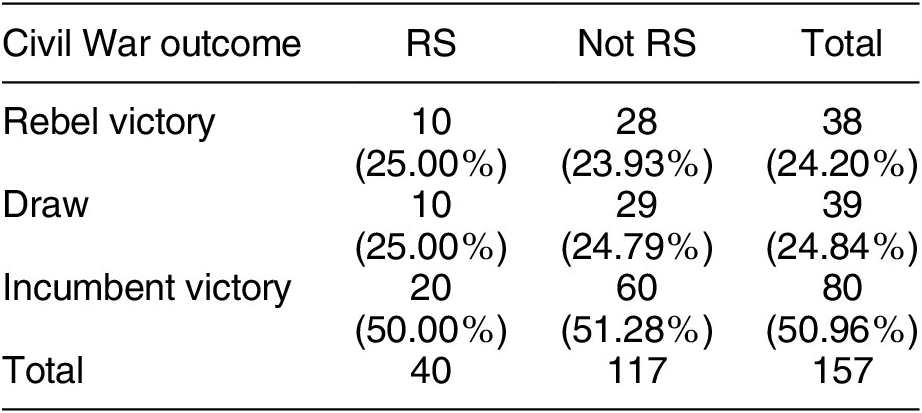

We now turn to the outcome of civil wars, which are categorized as incumbent loss (or rebel victory), draw, and incumbent victory (further details on variable coding can be found in Section A of the SM). The descriptive data (Table 5) suggest that RS rebels were not the kind of frequent winners in civil wars we expected based on their characteristics; in fact, they were as likely to be defeated as any other rebels.Footnote 22 We run multinomial logit models that confirm rebel type is not statistically significant in explaining how civil wars end (see Table B.5 of the SM).

Table 5. RS Rebels and Civil War Outcomes (1944–2016)

Note: Column percentages in parentheses.

In short, although RS rebels were distinct (and we argue, superior) from all other rebels in terms of organizational capacity and battlefield performance, we find—contra our expectations—that they failed to achieve superior outcomes. This is the case even though we document that RS rebels were more likely to establish forms of rebel governance (as coded by Stewart Reference Stewart2021) and diplomacy institutions (as coded by Huang Reference Huang2016); see Table B.6 of the SM. Why? We return to this point further below after examining the determinants of rebel type.

Cross-National Determinants of Rebel Type

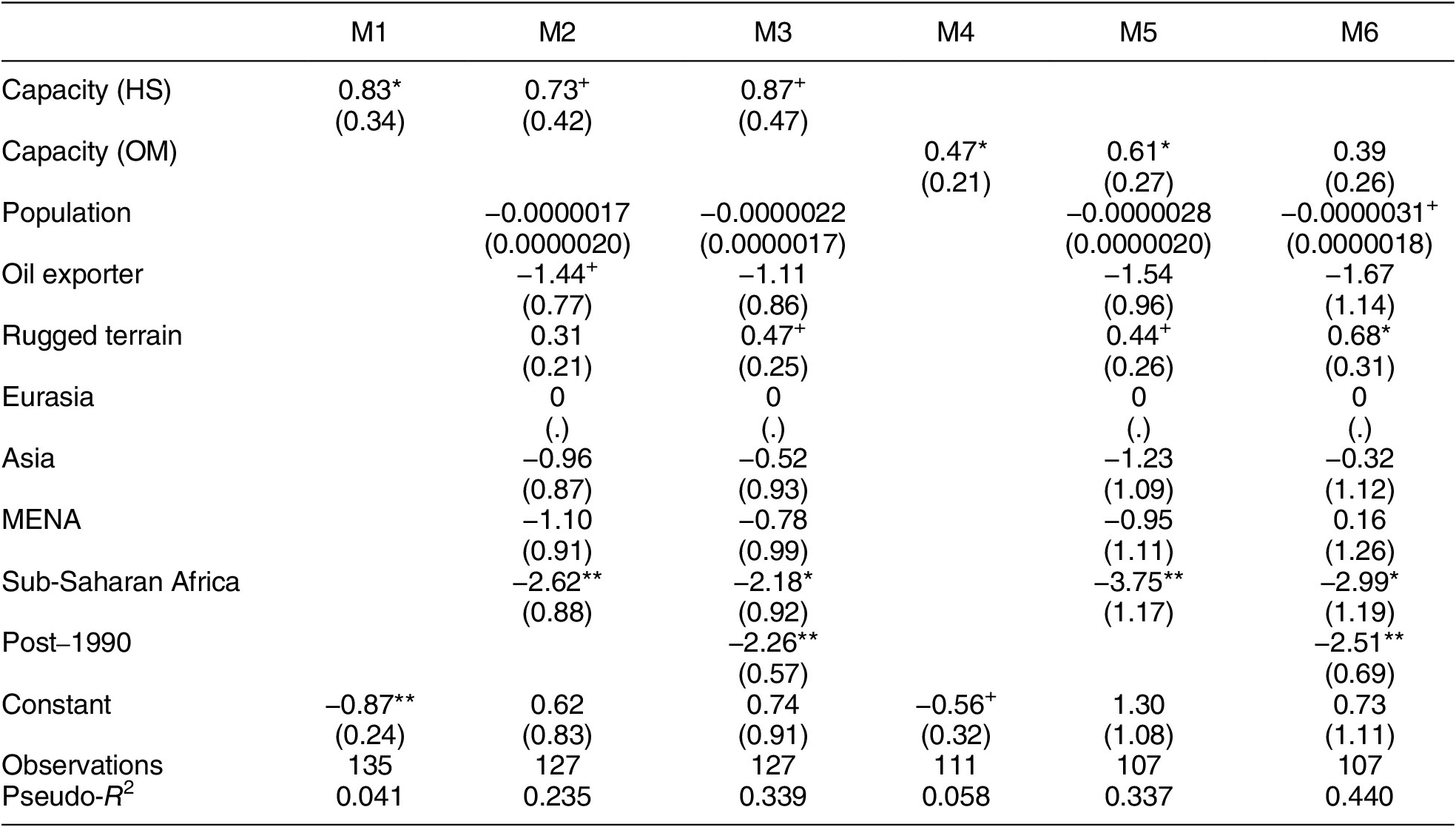

So far, we have confirmed most of our theoretical expectations: RS rebels were more likely to fight longer and more intense insurgencies—robust insurgencies, in other words—although their enhanced capacity did not help them produce more victories compared to other rebels. This begs the question of what, then, is driving rebel type. To address it, we explore the determinants of civil wars dominated by RS rebels compared to the other types of civil war (Table 6). Instead of GDP per capita, which is commonly used in the civil war literature to capture state capacity, we use two recent indices of state capacity introduced by Hanson and Sigman (HS) (Reference Hanson and Sigman2021) and O’Reilly and Murphy (OM) (Reference O’Reilly and Murphy2022), respectively, with values on the year before a civil war onset.Footnote 23 We run three sets of models: (i) a bivariate model with state capacity as the independent variable (M1); (ii) a model including several covariates (M2); and (iii) a model adding a post-Cold War binary indicator to the second one (M3). In M2 and M3, we use covariates that are common in the civil war onset literature, such as population, regional dummies, an indicator of whether the country is an oil exporter, and rugged terrain (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Nunn and Puga Reference Nunn and Puga2012).Footnote 24 It is worth noting here that rather than estimating the causes of civil war onset, we seek to investigate the cross-national factors associated with an increased likelihood of a civil war being dominated by RS rebels compared to other rebels.

Table 6. Logit on RS Rebels (1944–2016)

Note: All models report robust clustered standard errors by conflict (in parentheses). Models M1 to M3 use Hanson and Sigman’s (HS) capacity; M4 to M6 use O’Reilly and Murphy’s (OM) comprehensive capacity. These measures of state capacity are all lagged 1 year before the civil war onset. Latin America is the reference category for region. +

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

.

$ p<0.01 $

.

We find that in most specifications, RS rebels were more likely to fight civil wars in higher state capacity countries, as captured by the two indicators. This is in line with our characterization of those rebels as potentially high-performance ones and is consistent with Reno’s (Reference Reno2011) observation that the rebel and regime capacities tend to be matched.Footnote 25 The Cold War is the strongest correlate of wars with RS rebels, which were also more likely in Latin America and Asia.Footnote 26 Rugged terrain, a measure found to be correlated with the onset of insurgencies (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003), has a positive impact on RS civil wars, although it is not significant in all the model specifications.

Disentangling Political Ideology from External Funding

Did the characteristics of RS rebels flow from their political ideology or were they (and their ideology) derived from the fact that they received support from the USSR and other communist powers? If the latter is correct, could the RS ideology merely be window-dressing, intended to access badly needed foreign assistance? It is thorny to disentangle the two, as most RS rebels were recipients of foreign assistance (as were non-RS groups) and displayed an RS ideology, while also engaging in practices that were consistent with their ideology. Obviously, setting up an entire social movement from scratch and investing in time-consuming and costly political practices over long periods of time with a low expectation of success is hardly compatible with naked opportunism.

In the empirical analyses above, we have controlled for external support for rebels and for states. An additional way to disentangle these two factors is to investigate RS rebels who, due to particular historical or geographic reasons, did not receive outside funding. We analyzed the ideological orientation and practices of 12 groups for which our research indicated no external support from the USSR, China, Cuba, or another communist power. Some of these groups relied on their own resources, while others received assistance from noncommunist powers in the context of regional rivalries. With one exception (the BLA in Pakistan), and despite differences, they all clearly belong to the same species in terms of the factors we highlighted: disciplined and cohesive organizations with an emphasis on civilian mobilization. Of these groups, six were coded as MNL. With two exceptions, their socialist credentials proved long-lasting (the exceptions are the LTTE/Sri Lanka and Polisario/Morocco, which abandoned their socialist agenda); they adopted revolutionary goals and implemented the RS revolutionary war doctrine: FRETILIN (Indonesia), PKK (Turkey), EPLF, and TPLF (Ethiopia). With one exception, these groups were able to generate a substantial portion of their own financing (Polisario was supported by Algeria). Of the remaining six RS groups, all but one (the BLA in Pakistan) had a clear RS outlook: FARC (Colombia), SL (Peru), NPA (Philippines), CPI-M (India), and CPN-M (Nepal). Despite limited external support, they nevertheless displayed key characteristics associated with RS insurgencies in terms of organization and behavior.

An additional way to assess the degree to which the ideology of RS rebels was real rather than epiphenomenal or opportunistic is to look at external shocks. The EPLF is a case in point. Initially supported by the Soviet Union, East Germany, South Yemen, and Cuba, it lost all support after Ethiopia’s Marxist–Leninist coup of 1974, when the Soviet Union shifted its support to the new Ethiopian communist military regime. Losing external support, however, did not cause the EPLF to change its ideology, goals, or methods; it retained its radical revolutionary zeal and eventually succeeded in winning the war (Stewart Reference Stewart2021, 97–136; Woldemariam Reference Woldemariam2018).

The end of the Cold War offers an obvious instance of an external funding shock. Fortuna (Reference Fortuna2018) examines the trajectory of the full set of RS insurgencies that were active in 1989. There were 25 RS groups fighting in 20 countries in 1989, just before the Cold War ended. Of those, 44% reached a peace agreement at some point after the end of the Cold War. Most of the remaining half fought on to 1996, and several continued to fight well into the twenty-first century—in fact, a surprising 16% were still fighting in 2018. Originally self-funded groups were more likely to keep fighting. Furthermore, of the original RS insurgent groups still active in 1996, the majority (54.5%) continued to openly adhere to an RS identity. Fortuna (Reference Fortuna2018, 70) concludes that “the strong path-dependent dynamics of RS insurgent groups—including cohesion, coherence, and normative commitments to the Marxist cause—may have created significant resiliency within many of the groups.” Although the end of the Cold War had a suppressive effect on new RS insurgencies, it did not cause the majority of existing ones to shed their ideology.

Assessing the Effects of Fighting RS Rebels on State Capacity

As noted above, we are puzzled by the fact that RS rebellions did not translate into more successful outcomes for rebels (Table 5). The discrepancy between RS group capacity and the outcomes they were able to achieve opens a new research agenda whose surface we can only scratch here. We conjecture that the higher capacity of RS rebels raised the credibility of the existential challenge they posed to incumbent regimes. In turn, this challenge spurred a considerable counter-effort, attracting external support for these regimes and forcing them to reorganize and step up their game, thus contributing to their victory. This effort was not limited to the implementation of counterinsurgency strategies that combined military tactics with policy reform; it also spurred policy innovations, particularly rural modernization campaigns (Looney Reference Looney2021) built around new counterrevolutionary political and social coalitions, created to defeat RS insurgencies. As Slater and Smith (Reference Slater and Rush Smith2016) note, counterrevolutions in postcolonial Asia and Africa have been distinctively and exceedingly productive of durable political order—in ways that go beyond garnering foreign support. On the one hand, wealthy elites threatened by revolutionary insurgencies seeking to expropriate them were willing to comply with higher direct taxation to finance the counterrevolution. Indeed, counterrevolutionary regimes were able to build some of the strongest tax states in the developing world, allowing them to sustain popular spending policies and patronage practices even in hard economic times. On the other hand, capitalist expansion, that is, alignment with the United States against the Soviet Union, facilitated economic growth and the provision of public goods. As a result, many counterrevolutionary governments succeeded in suppressing RS insurgencies and preserving the existing social order, albeit in a new form (Slater and Smith Reference Slater and Rush Smith2016, 1486–7). For instance, the insurgency waged by the Malayan Communist Party during the late 1940s and early 1950s prompted massive investments in state coercive and fiscal capacity (Slater Reference Slater2010, 79–90). In the same vein, and in the context of its fight against the Sendero Luminoso insurgency (1980–92), the Peruvian state provided districts that were either contested or controlled by the rebels with higher levels of state personal and public service provision, thus strengthening its presence in areas where it had been extremely weak before the insurgency (Kreiman Reference Kreiman2022).

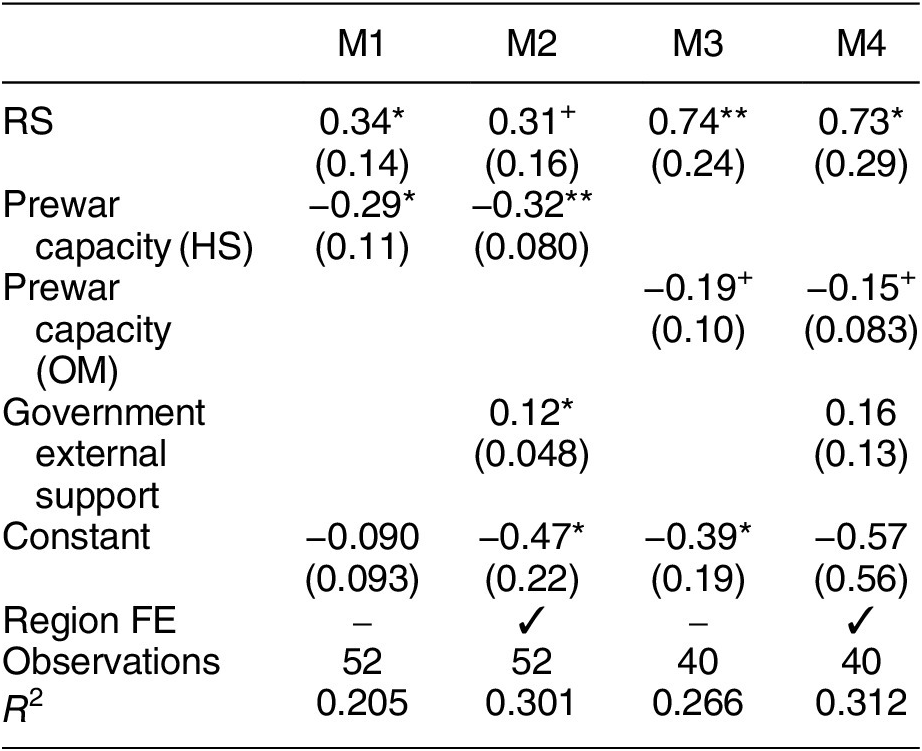

We use the HS and OM indices of state capacity to assess this conjecture with our cross-national dataset, focusing on states that did not lose to rebels.Footnote 27 In the linear regression analyses presented in Table 7, the dependent variable is the difference between the capacity index in the year after the war ended minus the capacity index in the year before the war started. We control for prewar levels of capacity and (in a second set of models, M2 and M4) for government external support. We also include regional dummies in M2 and M4. The coefficient for RS rebels is positive and significant in all four models. In M2, government external support also has a positive coefficient, but it does not wash out the effect of RS. Although these results warrant additional research, they are broadly consistent with the conjecture that states that faced RS rebels did step up their game and became stronger (or more capable) as a result.Footnote 28

Table 7. RS and State Capacity Growth

Note: All models report robust clustered standard errors by conflict (in parentheses). The universe of cases in this table are civil wars that started before 1991 and that were not won by the rebels. +

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

.

$ p<0.01 $

.

Ironically, then, RS rebels may have contributed to the resilience and strengthening of the regimes they challenged and, in an indirect way, to state building rather than state failure. This is surprising considering the widespread association of civil war with state failure. It is likely, instead, that a subset of civil wars might be associated with state consolidation (Balcells and Kalyvas Reference Balcells and Kalyvas2014, 1412). In part, this might be due to the conflict outcome. As Schenoni (Reference Schenoni2024) shows, victorious incumbents in interstate wars raise the capacity of their states. Our evidence suggests an additional twist to this thesis: incumbents defeating capable rebels may produce a similar rise in state capacity.

This last point suggests an additional implication. During the Cold War, civil wars rarely ended with negotiated settlements (Howard and Stark Reference Howard and Stark2018). However, following its end and the advent of unipolarity, this shifted dramatically: negotiated settlements became now much more common (at least until 2001), often as part of broader political agreements emphasizing democratization and power-sharing. While this shift was seen, and rightly so, as a positive development, particularly from a humanitarian perspective, its overall record remains mixed: conflict recurrence increased (Toft Reference Toft2010), new democracies were poorly institutionalized (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2015)—particularly when externally promoted (Hippler Reference Hippler2008)—and violence persisted, albeit in different, nonwar forms (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2010).

CONCLUSION

We have argued that RS ideology, a key feature in the civil wars of the Cold War era, shaped them in decisive and somewhat unexpected ways. First, RS rebels had a very specific war-fighting preference, intimately linked to their revolutionary war doctrine: they tended to fight irregular wars and did so much more consistently than any other type of rebel. Given that irregular war was a warfighting method of choice in about half the civil wars fought after 1944, the close association between RS rebels and irregular war at a rate surpassing 80% is altogether striking. Equally telling is the fact that the MNL rebels of the Cold War, which combined revolutionary socialism with secessionist goals, diverged from non-Marxist secessionist rebels in that they also fought in ways closely matching their non-secessionist RS peers, that is, using irregular warfare. Overall, RS rebels fought more intense and longer irregular wars or robust insurgencies, a fact reflective of their superior organizational and military capacity compared to other types of rebels. In the end, however, RS rebels were no more likely to produce victories compared to other rebels. We provide suggestive evidence that states that fought RS rebels and won were able to raise their capacity more than states also fighting (and winning) against other types of rebels.

We have triangulated qualitative and quantitative evidence to show that a political ideology that emerged and spread during the Cold War era was consequential for armed conflict in a number of empirically observable ways. We have also provided evidence, suggesting that this ideology cannot be reduced to an epiphenomenon of the rebels’ quest for foreign support; it reflected, instead, in a significant part at least, a choice that led to the adoption of practices that enhanced their military capacity. We identified two processes through which ideology helped generate attributes that translated into improved battlefield performance: cohesive and disciplined organizations and a dense web of interactions with the civilian population. We argued that, although not unique to RS rebels, these attributes were more likely to accrue to them vis-à-vis other rebels because of two features: their revolutionary war doctrine and their transformational and transnational character. While their doctrine could be used by non-RS rebels, this was much harder to achieve by nontransformative and nontransnational actors. Lastly, we have argued that the RS rebels’ inability to translate their improved capacity into more frequent victories could be explained by the fact that they posed a significant threat to incumbent regimes, one that was both existential and credible, thus inciting an equally significant counter-mobilization. Paradoxically, civil wars fought by RS rebels likely ended up strengthening these regimes rather than wrecking them—a paradox that we help to unpack.

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the ensuing “War on Terror,” the world entered a new era, one characterized by a remarkable increase in the share of conflicts involving Islamist rebel groups, which went from around 5% in 1990 to more than 40% in 2014 (Fearon Reference Fearon2017; Gleditsch and Rudolfsen Reference Gleditsch and Rudolfsen2016). The core characteristics of Islamist insurgencies, from their emphasis on a transformational worldview, the organization of highly motivated armies coupled with a transnational militant network, and the setup of extensive state-like institutions, all the way to the provision of public goods at the local level, point to a strong ideological outlook (Revkin Reference Revkin2020)—one that can be described as revolutionary (Hegghammer Reference Hegghammer2020; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2018; Stewart Reference Stewart2021) rather than primarily “religious” (Nilsson and Svensson Reference Nilsson and Svensson2021) or simply terrorist (Byman Reference Byman2015), “radical,” or “extremist” (Walter Reference Walter2017). Islamist rebels also are fighting civil wars that credibly challenge incumbent regimes in existential ways (Basedau, Deitch, and Zellman Reference Basedau, Deitch and Zellman2022; Nilsson and Svensson Reference Nilsson and Svensson2021). These conflicts are often intractable, less amenable to peacekeeping and negotiated settlements (Howard and Stark Reference Howard and Stark2018), and prone to high rates of recurrence (Nilsson and Svensson Reference Nilsson and Svensson2021). The region most affected, the Middle East and North Africa, also tends to be a place where peacekeeping is almost totally absent (Fearon Reference Fearon2017).

However, what made victory elusive to the RS rebels of the Cold War might make them equally, if not more, elusive to Islamist rebels. Their radicalism and the threat they represent to the existing order are likely to spur substantial counter-mobilization, perhaps even helping to shore up the regimes they challenge. This might push some of them to moderate their ideological outlook, as was the case with HTS in Syria (Drevon Reference Drevon2024). Furthermore, the absence of a Cold War-like global bipolar competition deprives Islamists of the kind of foreign patronage that many RS rebels had access to.

To conclude, political ideology continues to matter in ways that come into sharper focus once placed in the proper macro-historical framework. This is why paying close attention to its impact, while also acknowledging its historical embeddedness and relation to a specific world-historical time, remains a sensible research strategy.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425000188.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZWKJTP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their gratitude for research assistance to Benjamin Burnley, Anna Feuer, Sarah Fisher, Da Sul Kim, Jessica Norris, and quite especially Simón Ballesteros and Benjamin Reese. The authors would like to thank audiences at the Harvard International Relations workshop, the UC Berkeley Comparative Politics Workshop, Carlos III-Juan March Institute, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), and panels at ISA and APSA annual meetings for feedback on previous versions of the project. They also appreciate the feedback and suggestions from Killian Clarke, Roger Fortuna, Daniel Kselman, Giovanni Mantilla, Mikael Naghizadeh, William Nomikos, Ting Ni, Lahra Smith, Luis Schiumerini, Ken Opalo, Costantino Pischedda, Desh Girod, Christoph Dworschak, Diana Kim, and Luis de la Calle. They thank Nicholas Sambanis and Jonah Schulhofer-Wohl for sharing their civil wars dataset. Finally, the authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the handling editors for their valuable feedback on the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm that this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.