INTRODUCTION

Women can face a variety of barriers in their attempt not only to access government services but also justice more broadly (Agnes, Chandra, and Basu Reference Agnes, Chandra and Basu2016; Duflo Reference Duflo2005). While representation for women in powerful positions has been shown to improve service provision for female citizens and increase comfort with approaching administrators (Chattopadhyay and Duflo Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004; Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Mani, Mishra and Topalova2012), this literature has been restricted to quotas that incorporate women into existing state institutions. Others have theorized that representation in the form of creating separate group-specific arrangements may lead to more substantive outcomes; in such settings, minorities would be entirely unconstrained by the majority (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2015; Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2018) and could therefore efficiently provide services to in-groups (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2017).

A variety of group-specific measures have emerged as mechanisms to articulate and accommodate the preferences of women—for example, all-female parties in Ireland (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2014), female self-help groups in India (Prillaman Reference Prillaman2017), women’s justice centers in Peru (Kavanaugh, Sviatschi, and Trako Reference Kavanaugh, Sviatschi and Trako2017), and even gender violence courts with female judges in El Salvador (Lin, Burke, and Brigida Reference Lin, Burke and Brigida2018). The notion behind establishing group-specific mechanisms is not new. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the U.S. feminist movement began demanding separate spheres from men, which led to the rise of all-female institutions in health, banking, politics, legal aid, and education across the United States as a way to empower women (Craig Reference Craig1994; Freedman Reference Freedman1979). During this era, all-female parties like the Woman’s Peace Party were seen as better able to represent women’s policy preferences (Craig Reference Craig1994); similarly, separate police stations called Women’s Bureaus in American cities were viewed as effective venues to accommodate victims of sexual violence as well as increase policewomen’s participation in the force (Owings Reference Owings1925; Schulz Reference Schulz2004).Footnote 1

While fully abolished by midcentury in the United States (Lewis Reference Lewis1967), specialized police stations for women have been established across the Global South in Argentina, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador, Ghana, Kosovo, Sierra Leonne, and the Philippines such that female victims of violence can be accommodated by policewomen, potentially separated from patriarchal attitudes (Perova and Reynolds Reference Perova and Reynolds2017).Footnote 2 Afghanistan has established Family Response Units staffed by policewomen trained by the UN to tackle domestic violence, and Brazil has created hundreds of all-women police stations called Delegacia de Defesa da Mulher.

Can such institutions promote women’s participation in the police as well as increase victims’ formal access to justice? This study is situated in India; the country houses the largest number of all-women stations in the world and is a setting with low levels of police legitimacy where citizens, especially women, are reluctant about approaching law enforcement (Stepan, Linz, and Yadav Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011). Methodologically, I create a fine-grained dataset of crime based on millions of individual-level police station reports—a substantial advance on previous studies of violence in the Subcontinent—and leverage the manner in which all-women stations were implemented in an Indian state (Haryana). I also use official logs, a large-scale survey, and eight months of ethnographic research in and around police stations across Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana.

I find that all-women police stations do not increase levels of registered crime or change the status of cases in the criminal justice system. Instead, they reduce gendered cases accommodated at standard police stations by enabling (male) officers to pass cases on. The intervention erects barriers for victims in their attempt to access justice by increasing travel cost. I provide qualitative evidence that such bodies promote the counseling of complainants at the expense of registration of cases or arrest of (male) suspects. A large-scale survey reveals a negative association between proximity to all-women stations and particular notions about policewomen. I also demonstrate that all-women stations lower the formal responsibilities for policewomen working in the agency, preventing them from gaining the same experience as men. This may, in turn, hinder women’s advancement in the police bureaucracy and perpetuate stereotyping.

Representation can be designed on the basis of inclusion (e.g., via quotas and affirmative action that bring diverse groups into existing institutions) or through separation (e.g., in the form of group-specific enclaves). I argue that identity-based enclaves may counter the goals of representation by leading to the segregation rather than integration of gender issues. The study has implications for several strands of research including on violence against women (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2012; Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Mani, Mishra and Topalova2012), bureaucratic performance and service delivery (Gulzar and Pasquale Reference Gulzar and Pasquale2017; Keiser et al. Reference Keiser, Wilkins, Meier and Holland2002), and the emerging literature on citizen interactions with law enforcement in the Global South (Blair, Karim, and Morse Reference Blair, Karim and Morse2019; Karim Reference Karim2020). The findings also contribute to the literature on policies of inclusion by showing how outcomes greatly depend on institutional design (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2017; Parthasarathy Reference Parthasarathy2017).

This article is structured as follows. I review existing literature on representation as separation and then provide a background on gender and policing in India. After presenting the First-Information-Report dataset, I describe the functioning of all-women police stations in north India, and Haryana state in particular. I then probe the impact of such bodies vis-à-vis five outcomes, including with the help of an interrupted time-series analysis (Hausman and Rapson Reference Hausman and Rapson2018). Finally, I point to two critical mechanisms and then conclude.

Representation, Separation, and Service Delivery

Gender representation in administrative agencies is understudied; moreover, existing research on the topic presents ambiguous evidence about its impact. It is especially unclear as to whether group-specific arrangements for women would generate positive outcomes.

Literature from the Global North does show that gender representation in the police increases the likelihood women approach law enforcement (Riccucci, Van Ryzin, and Lavena Reference Riccucci, Ryzin and Lavena2014). Meier and Nicholson-Crotty (Reference Meier and Nicholson-Crotty2006) contend that the presence of policewomen in the force is associated with higher rates of arrest for sexual assault. This is may be particularly true when policewomen are conferred front-line authority (Andrews and Johnston Miller Reference Andrews and Miller2013). Policewomen sensitize policemen to gender biases, and women feel more comfortable reporting crimes to policewomen (Miller and Segal Reference Miller and Segal2019).

However, research on policing in deeply patriarchal settings paints a more complicated picture. Karim et al. (Reference Karim, Gilligan, Blair and Beardsley2018) find no evidence that gender balancing in law enforcement increases sensitivity to women’s issues in Liberia. Survey experiments with Ugandan officers show that the presence of women in the police may not improve service quality and policewomen are neither more ethical nor reliable (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Rieger, Bedi and Hout2017). Cooper (Reference Cooper2018) finds that citizens in Papua New Guinea may turn to traditional conflict resolution mechanisms in settings where policewomen have a prominent role.

Some contend that separate spheres for women in the criminal justice system may go farther in facilitating claim-making, promoting policewomen’s professionalization, and addressing violence against women. Kavanaugh, Sviatschi, and Trako (Reference Kavanaugh, Sviatschi and Trako2017) find that women’s justice centers in Peru improve female welfare and reduce domestic violence. Amaral, Bhalotra, and Prakash (Reference Amaral, Bhalotra and Prakash2018) suggest that group-specific institutions in India are associated with greater levels of crime registration. Research from Tamil Nadu suggests that all-women stations improve policewomen’s career trajectory in the bureaucracy (Natarajan Reference Natarajan2008), and Pruitt (Reference Pruitt2016) suggests that all-female police units in Liberia help to normalize women’s participation in regulatory agencies. Perova and Reynolds (Reference Perova and Reynolds2017) persuasively argue that Brazilian all-women police stations may have an overall weak impact in terms of addressing intimate partner violence, but may be effective in metropolitan settings where there are less traditional social norms.

However, qualitative studies from Brazil are more cautionary about the idea of separate spheres. Santos (Reference Santos2004; Reference Santos2005) describes how some Brazilian feminists were skeptical of all-women police stations when they were opened in São Paulo precisely because the “separatist strategy” was rooted in the essentialist notion that women, by their very nature, were more considerate toward in-groups. This skepticism may have been well founded because, Santos (Reference Santos2004) finds, female officers invariably blame the victim and do not believe sexual violence to be on the same par as other crimes. Isolating female officers into “women’s spaces” without any “institutionalized gender-based training” may not always be effective; the “separatist strategy” fails to acknowledge that policewomen and victims may have opposing interests (50–51).Footnote 3

Hautzinger (Reference Hautzinger2007) and Nelson (Reference Nelson1996) echo this argument. Hautzinger (Reference Hautzinger2007) shows that policewomen sometimes overcompensate in an attempt to match a norm set by a hypermasculine police subculture, and they may be particularly dismissive of complaints related to gender-based violence. Relatedly, Nelson (Reference Nelson1996) makes the case that female officers may be frustrated that they are associated with crimes perceived as “minor” when serving in Brazilian all-women stations; this could lower job performance because policewomen may channel their dissatisfaction about being separated from “mainstream” police work toward complainants.

These insights contrast with political science literature on gender-based enclaves and deliberation. Mendelberg, Karpowitz, and Oliphant (Reference Mendelberg, Karpowitz and Oliphant2014) argue that all-female enclaves can empower women by removing members of an authoritative identity (men) and facilitate responsiveness to women’s interests. Karpowitz and Mendelberg (Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2018, 1137) note that, “In groups consisting entirely of their own members, disadvantaged individuals may be best able to develop their own capacity, and come to articulate their own perspectives and preferences… . In such enclaves, women may provide each other with mutual psychological support, further enhancing their personal empowerment. Women may focus on their distinctive concerns as women, giving them the autonomy to prioritize issues that may otherwise be shunted aside.”

Yet, one can imagine negative outcomes associated with enclaves, especially because segregation is in the design. Let us suppose that a homogeneous enclave for women is created in a legislature (Mendelberg, Karpowitz, and Oliphant Reference Mendelberg, Karpowitz and Oliphant2014). Research on Latin American legislatures shows that women are already isolated on committees related to social welfare or women’s issues and marginalized from those related to national security or foreign policy (Michelle Heath, Schwindt-Bayer, and Taylor-Robinson Reference Michelle Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson2005). It is therefore plausible that the creation of an enclave might perpetuate such occupational segregation and provide standard committees an excuse to disregard or ignore gender issues entirely. Further, Karpowitz and Mendelberg (Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2018) note that women in enclaves are more likely to focus on “care” topics like “family” rather than those of “distinctive interest to men” such as “finance.” Yet, if women in enclaves do not adequately engage in non-gendered issues, this may hurt their career advancement. As Sapiro (Reference Sapiro1981, 712) notes, on the pretext of empowerment, segregation can “ghettoize” rather than facilitate women’s substantive representation by pushing gender issues away from the mainstream and into the periphery.

Applying this logic to law enforcement, the creation of all-women stations may enable standard police stations to turn away victims of sexual violence by using the institutions as an excuse to lighten their own caseload, thereby hindering victims from speedily accessing justice. The separation of policewomen may also fail to improve police services if officers continue to hold the belief that reconciliation of victims with abusers is preferable to arrest of suspects (Sherman and Berk Reference Sherman and Berk1984). In fact, rather than improving policewomen’s professionalization (Natarajan Reference Natarajan2008), enclaves may associate them with specific roles, thereby reinforcing stereotypes that women do not have the skills to carry out tasks that are not gendered (Martin Reference Martin1999).

I make a distinction between two categories: “enclave” and “inclusive” representation. Quotas or affirmative action recruitment are forms of “inclusive” representation, whereas group-specific institutions such as women-only courts or police stations can be referred to as “enclave” representation. I attempt to reconcile the sometimes contradictory existing evidence on representation as separation by probing whether the creation of enclaves in law enforcement affects (a) gendered crime registration, (b) cases investigated by policewomen, (c) cases with female complainants, (d) the disbursal of cases to the courts, and (e) perceptions of female officers.

CONTEXT

Gender and Policing in India

Indian law enforcement is divided between an elite bureaucracy called the Indian Police Service and state/provincial officials. Policing on the ground in terms of responding to citizen complaints, registering crimes, and carrying out investigations is done almost entirely by the provincial ranks that serve at local police stations called thanas. These institutions are generally run by an inspector called a station house officer, who is supported by sub-inspectors, assistant sub-inspectors, and constables. Typically, the station house officer hears a victim’s complaint; a crime report—also known as a First-Information-Report or FIR—may then be lodged and assigned to an officer for investigation. Registration of a crime report is a citizen’s first step towards formal access to justice.

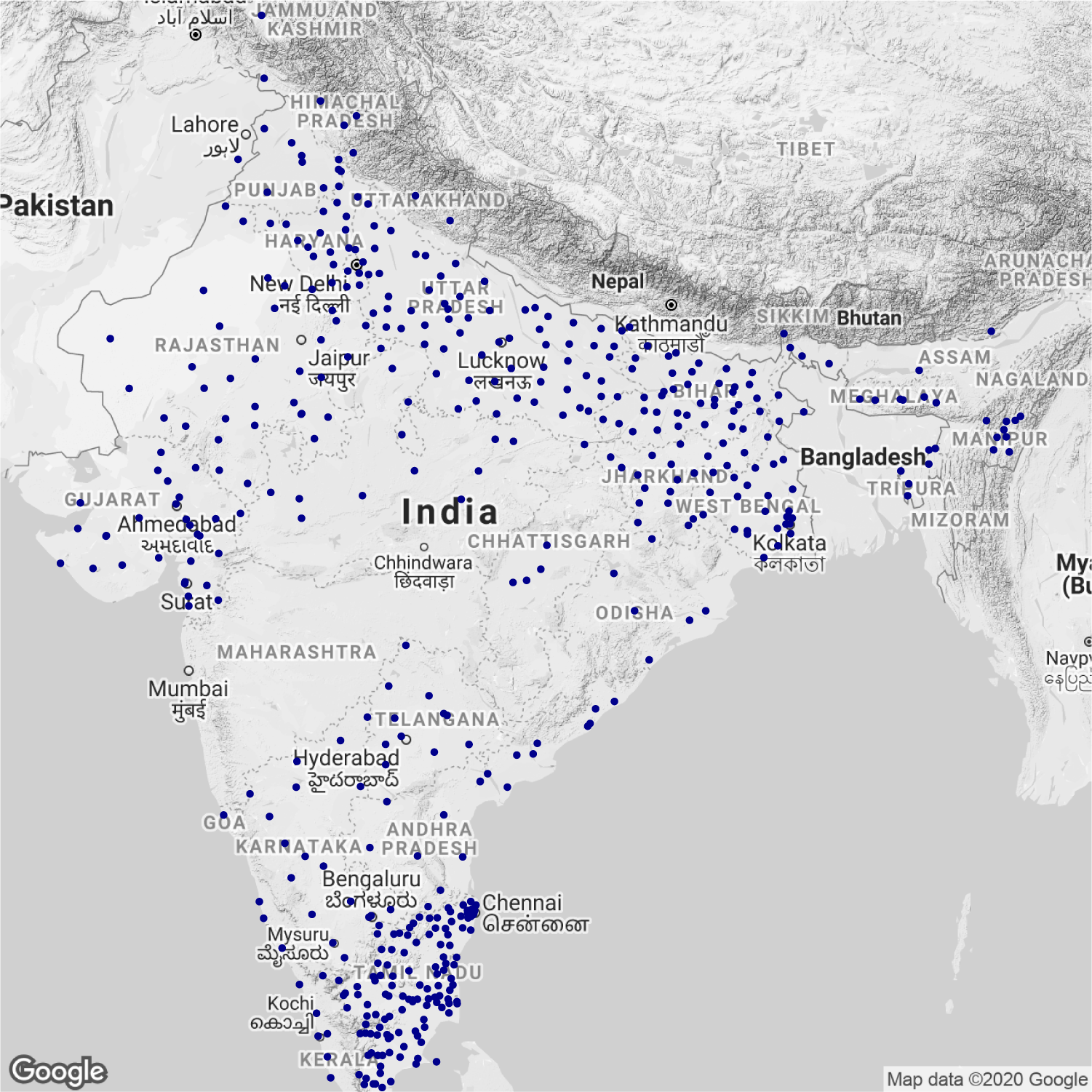

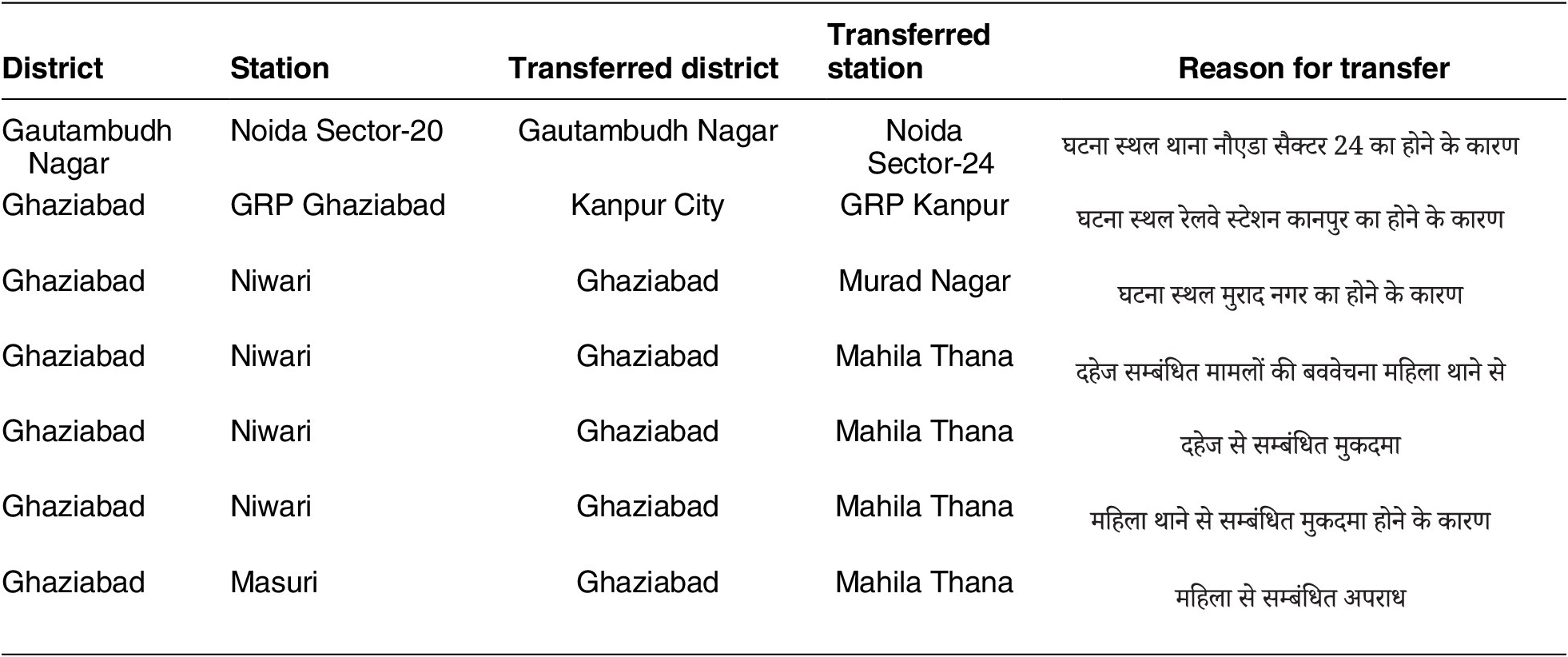

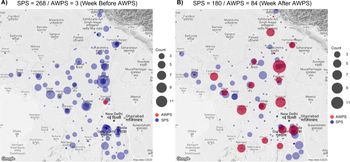

For years, the federal government has promoted the policy of increasing the number of women in law enforcement (Sabha Reference Sabha2012). Most states have approved a 33% quota for women in their forces, and several have established all-women police stations, of which there are more than 500 in operation (Figure 1). All-women stations specialize in tackling crimes like dowry harassment,Footnote 4 rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment, acid attacks, and so on. Aside from Tamil Nadu, all-women stations are usually located in the administrative headquarters of districts in states that adopted the policy.Footnote 5 Policewomen can be posted at a standard station or all-women station, the main distinction being that the latter is run entirely by female staff. All-women stations are additive; a victim may register a crime in the standard police station near where the crime occurred or to the all-women station in the district headquarters. There is no obligation that women must register crime at all-women stations.

Figure 1. Locations of All-Women Police Stations (AWPS) in India

The establishment of all-women stations is an implicit acknowledgment that law enforcement can be dismissive of sexual violence. All-women stations are based on Indian policy makers’ presumption that policewomen are fairer and more empathetic toward other women (Sabha Reference Sabha2012). Some lawmakers have noted that, even with increased gender representation in the force, policewomen might still be constrained from channeling their perceived skills in relation to in-groups; instead, the separation of female officers in group-specific institutions would potentially create a space removed from patriarchy. Policy makers have argued, “The role of women police in promoting gender sensitivity, dealing with causes related to women and promoting friendly behavioral sub-culture in the police are considered crucial” (Sabha Reference Sabha2012, 9) or “The setting up of specialized women police stations has been seen as a progressive step as issues like domestic violence, dowry harassment, and child abuse invariably end up at police stations. Women police, by their nature, are better equipped to take a sympathetic approach” (Sabha Reference Sabha2012, 14). The intuition behind enclaves is that they would improve policing quality (e.g., registration rates of gender-based violence), and therefore perceptions of law enforcement.

The First-Information-Report (FIR) Dataset

Data on crime in India typically come from official statistics published by the National Crime and Records Bureau. However, these statistics have been known to be unreliable and susceptible to manipulation (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson, Jayal and Mehta2010). The present study introduces a new dataset.

In 2009, following the Mumbai terror attacks, the Indian government initiated the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and System (CCTNS). The goal of the project was to create a national database of criminals as well as electronically link police stations and crime reports. Following a 2016 Supreme Court ruling that made police records accessible, I harvested and parsed into a readable file crime registrations from several states.Footnote 6 For reports that were not available because of their sensitive nature, I was granted assistance by the Indian police.Footnote 7 The present study includes crimes registered in the states of Bihar, Haryana, and five districts of Uttar Pradesh.Footnote 8

The dataset used in this study paints a more precise portrait of crime in India for at least five reasons. First, unlike pre-CCTNS data, which are district aggregations of crime, the FIR dataset is at the individual level. Second, official statistics do not always take into account expunged crime, whereby a case is stricken or canceled if believed to have been filed under false pretenses. Third, when a case comes to a police station (e.g., a case involving kidnapping and trespassing), in the official statistics it may be only the most serious violation that is recorded (i.e., kidnapping). In this way, official statistics may underweight the varieties of registered crime. Fourth, government statistics are published infrequently, making it difficult to gain insight about crime in a particular month, day, or hour. Fifth, government reports, unlike the FIR dataset, code crimes according to a particular schema that may change from year to year.

For non-sensitive cases, the FIR dataset contains—aside from variables such as dates and locations—details on victims, investigating officers, and suspects. Because names in South Asia typically evoke identity (e.g., gender, caste, religion), the names in the dataset were used to code gender. I used administrative lists to code the gender of individual police officers; for millions of victims and suspects, names were coded with the NamSor package in R and cross-checked manually. Names were coded as female that were unambiguously so, and therefore represent a lower bound.Footnote 9

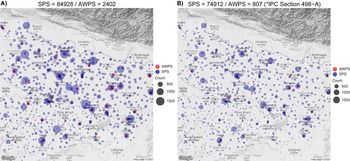

All-Women Stations and the Haryana Intervention

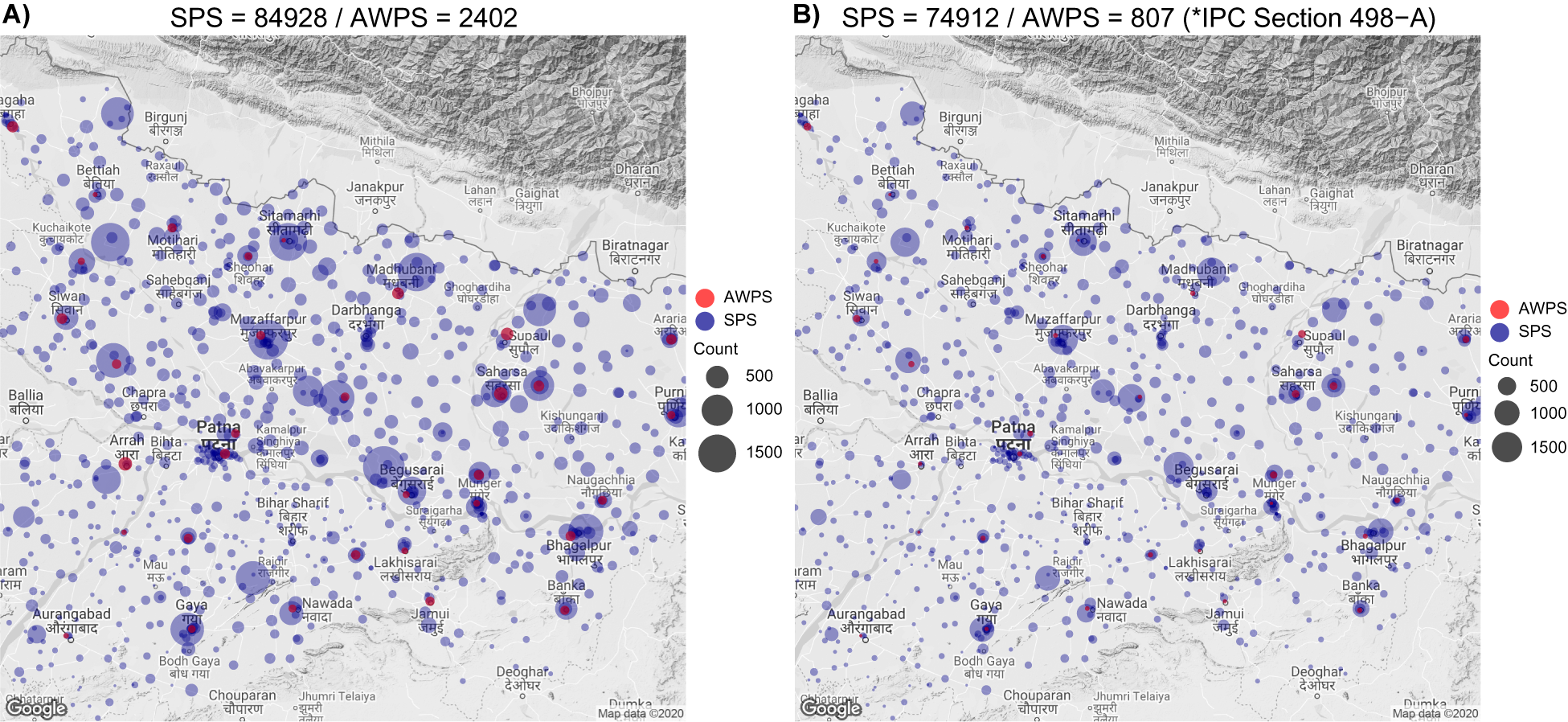

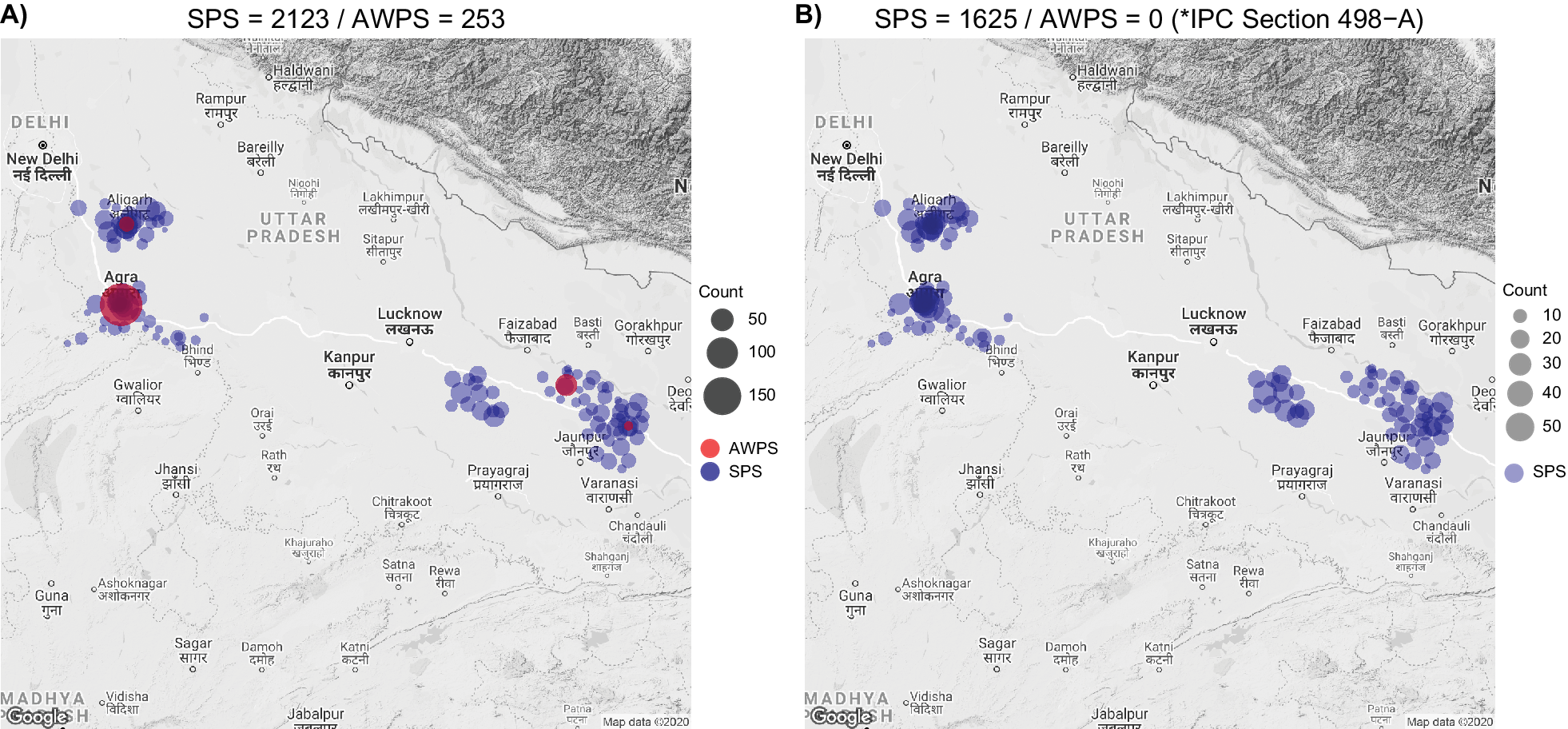

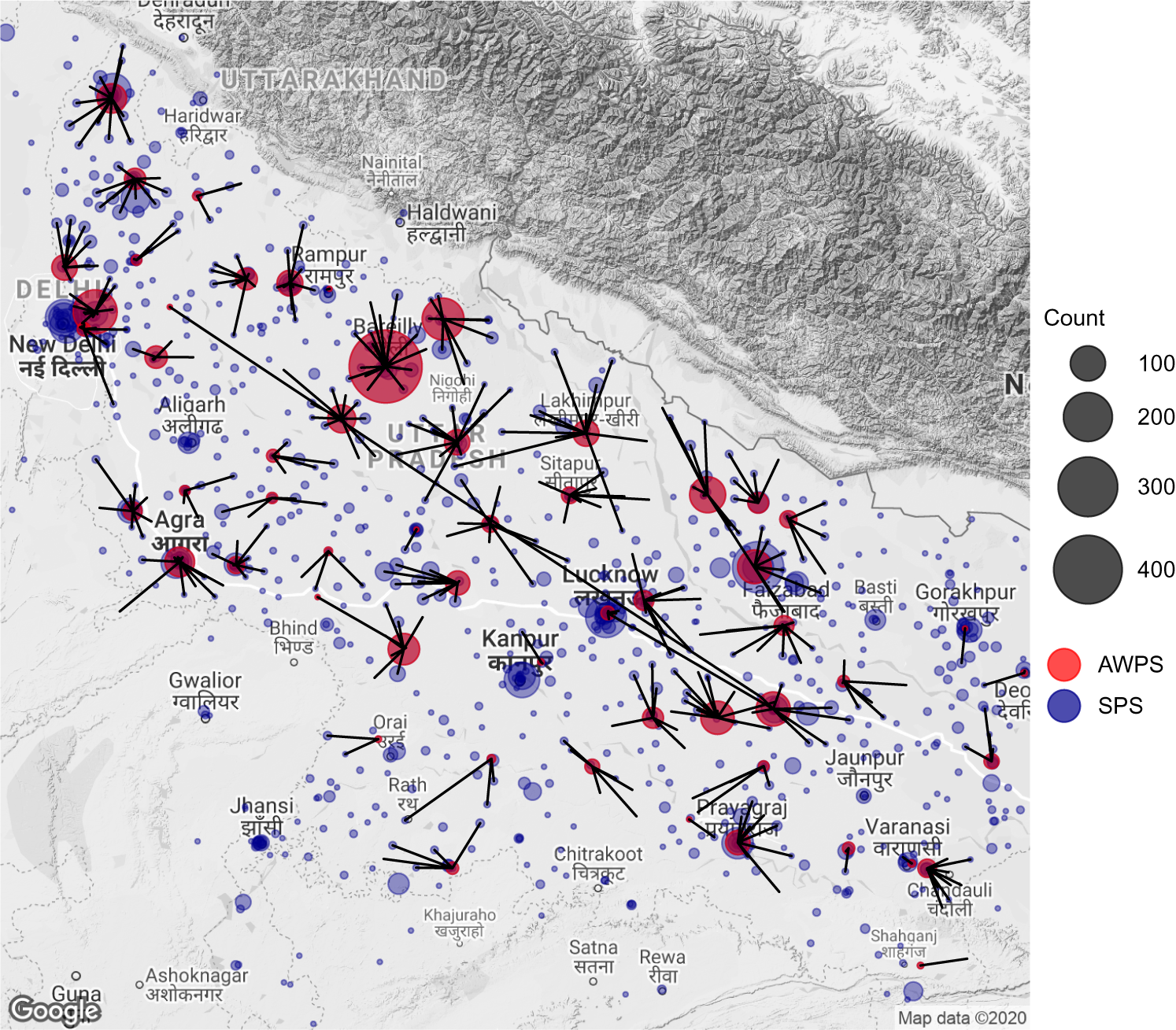

At a descriptive level, what kinds of cases do all-women police stations typically register? Figures 2 and 3 present the locations of police stations as well as the number of gendered crimes registered at standard and all-women stations across Bihar and five districts of Uttar Pradesh from 2015–2018.Footnote 10 The size of the dots represents the intensity (count) of registered crime. Panel A of Figures 2 and 3 show that crimes registered at all-women stations (red dots) represent just 2.7% of gendered cases in Bihar and 1% in Uttar Pradesh. In panel B, when excluding crimes related to dowry harassment or Section 498-A, the red dots virtually vanish, and the numbers drop to 1% and 0%, respectively. In other words, in two of India’s largest states, crime registered in all-women police stations accounts for a fraction of all gendered cases, and the cases that are registered relate to offenses involving a woman’s spouse and his family.

Figure 2. Gendered Crimes Registered at Standard and All-Women Stations (Bihar)

Figure 3. Gendered Crimes Registered at Standard and All-Women Stations (Uttar Pradesh)

To investigate the causal effect of all-women stations, I turn to Haryana, which serves as the only case with which to examine the effect of all-women stations using individual-level crime data before and after the implementation of the policy. The state is known for high levels of violence against women, honor killings, and a skewed sex ratio as a result of female infanticide/feticide. Survey data show that 88% of women in the state express being afraid of their spouse, 10 percentage points more than the national average (Appendix Table A18).

Haryana is the newest state to adopt all-women police stations; 20 institutions were opened in each of the state’s district headquarters on August 28, 2015, one year after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power, and eight months after the establishment of the CCTNS system.Footnote 11 There was no particular demand for all-women stations among citizens; in fact, some NGOs and feminist associations expressed concern about such a top-down effort at the expense of hiring more policewomen to work in standard police stations (Gilmore et al. Reference Gilmore, Srivastava, Daruwala and Prasad2015).

The institutions were opened on the same day across all districts, twenty-four days after a memo was issued by the state government that new segregated stations be built (Appendix Figure A3). For public relations (PR) reasons, the stations were opened on the day of the Hindu festival of Raksha Bandhan, a holiday that celebrates women’s protection. Foundation stones outside the police stations record the date as well as the names of the government officials that were present for the inauguration. Each police station came equipped with 30–40 policewomen (Mishra Reference Mishra2015; PTI 2015),Footnote 12 who were transferred from other offices.Footnote 13 Appendix Table A1 confirms that the stations began registering/investigating their first crime reports between August 28 and September 3, 2015, highlighting the fact that the institutions came equipped with among the most important resources: the CCTNS system.

In addition, Haryana did not implement a 33% gender quota in the police. Immediately before and after the intervention, the rate of policewomen serving in the force was stable (Appendix Figure A19). Moreover, over half of Haryana’s citizens have knowledge of all-women stations, the highest rate for any state in the union (Appendix Figure A14). Haryana happens to be a smaller state, and a majority of its residents live close to the special institutions; this is desirable because if all-women stations failed to have an impact, it would less likely be a factor of lack of awareness.

I carry out an interrupted time-series analysis, a form of regression discontinuity in which time is the running variable (Anderson Reference Anderson2014; Shadish, Cook, and Campbell Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell2001). Such designs have been known to produce estimates close to experimental benchmarks (St. Clair, Cook, and Hallberg Reference St. Clair, Cook and Hallberg2014). The discretion of the researcher is minimal in terms of coding treated and untreated units (Mummolo Reference Mummolo2018). The high frequency of data used, the exact moment of intervention, and the fact that the implementation of all-women police stations was unrelated to areas in which crime was increasing or decreasing, supports this design.

OUTCOMES

I study the period in Haryana from January 1, 2015, (when crime reports were made electronic) to August 8, 2017.Footnote 14 With the universe of registered cases, I examine the change in the rate of registered gendered crimeFootnote 15 on and subsequent to August 28, 2015. Gendered crimes are those that invoke at least one of the laws listed in the 2015 Haryana order (Appendix Figure A1 and Table A2). I also examine the proportion of crimes investigated by policewomen and cases with female victims. Formally, I estimate the following equation:

where Yt is the outcome for each day t since January 1, 2015, awps t is an indicator for when all-women stations came into effect, and β is the coefficient of interest. Days are days with 0 when the intervention begins and positive or negative otherwise. If the assumptions underpinning the RD are valid and εt does not change discontinuously on the day of intervention, the estimate β should be unbiased. Nevertheless, to increase precision and take into account seasonality, I include Xt as controls for the year, month, and day of the week when looking at all days from 2015–2017 (Anderson Reference Anderson2014). I include f(days) that represent quadratic and cubic functions on either side of the treatment threshold. Because expanding the time window increases the probability of bias, I run similar models in tighter bandwidths of 200- and 100-days around the intervention date and estimate HAC standard errors (Newey and West Reference Newey and West1987). Finally, I carry out a placebo test by estimating the equation with August 28, 2016, as the day of “treatment”—that is, one year after the intervention.

Cases of Gendered Crime

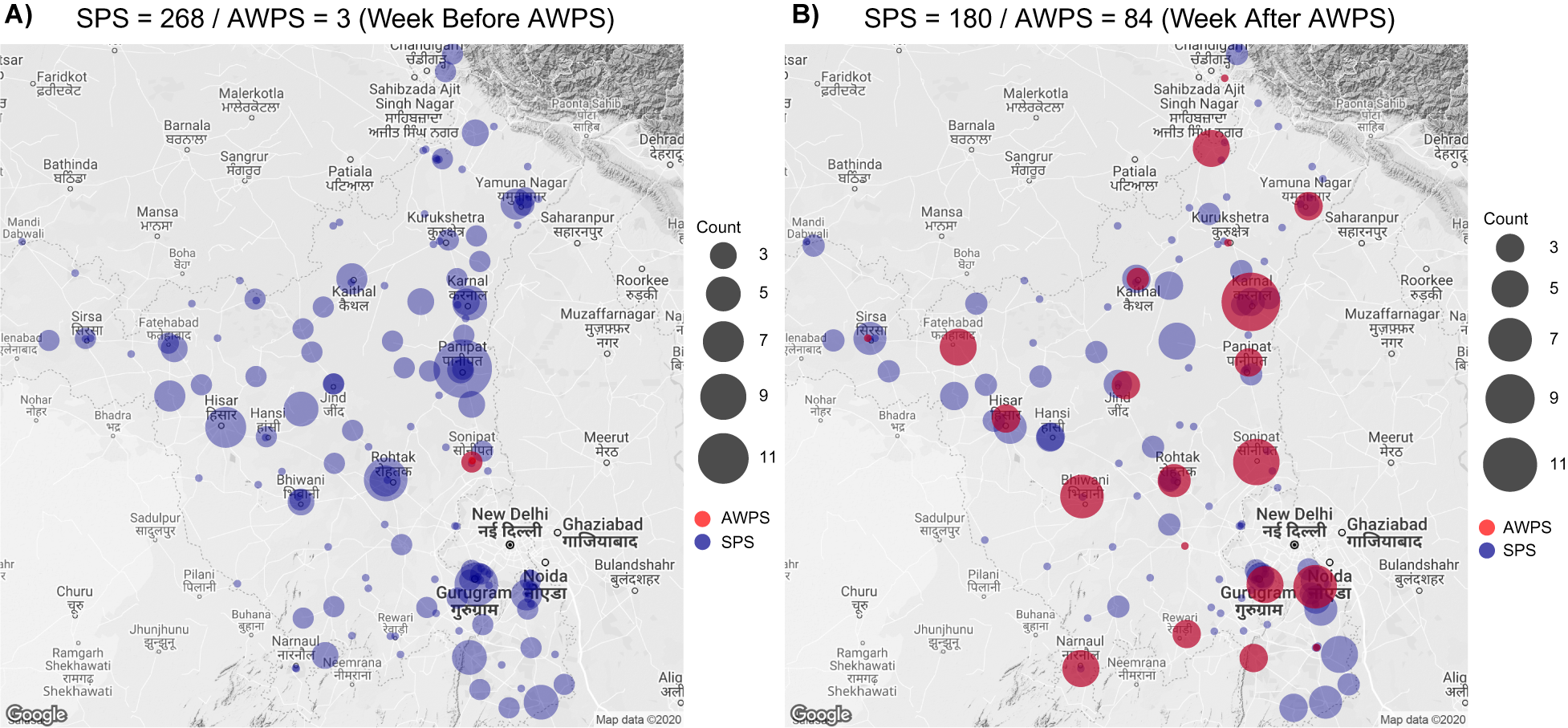

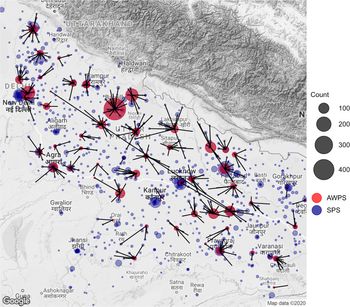

Figure 4—which includes the locations of Haryana’s police stations—highlights the spatial change in registered gendered crime the week before and after the intervention in the state. During the week of August 21–28, 2015, almost all gendered crimes were registered at standard police stations. The week following the creation of all-women stations, 32% of registered gendered crime was now tackled at the alternate venues. Yet, in aggregate terms, the total number of cases registered remained virtually identical across both weeks.Footnote 16

Figure 4. Spatial Displacement of Gendered Crime Registrations Due to Introduction of AWPS (Haryana)

Figure 5 presents the temporal change in registered gendered crime. Figure 5, panels A, B, and C include the 265 standard stations in the state as well as the 20 all-women stations created 239 days after January 1, 2015. Panel A highlights the absolute number of gendered crimes registered/investigated for each day and shows no level change. Panel B reflects the rate of gendered crime by highlighting its seasonality; whereas there is an upward trend long after the intervention (approximately 750 days following January 1, 2015), total crime is also increasing during this period (Appendix Figure A8). When examining the proportion of gendered crimes (daily number of gendered crimes registered divided by the total registrations per day), we see that all-women stations did not have an impact. The addition of new specialized police stations did not significantly affect the count, rate, or proportion of registered gendered crimes.

Figure 5. Temporal Change in Gendered Crime Registrations Pre/Post AWPS Intervention

However, when we restrict the sample to only the 265 standard police stations, we find sharp discontinuities in Figure 5, panels D, E, and F. In panel D, we see a drop in the absolute number of gendered crimes recorded per day, and panel E highlights a steep decline in the rate of gendered crimes registered. The proportion of gendered crimes in panel F drops substantially, and does not return to its original level for the subsequent two years. Broadly, panels D, E, and F show that the incoming caseload of gendered crimes was now moved out of standard police stations; either female victims of violence began visiting enclaves of their own volition overnight or they were turned away from standard police stations and asked to travel to the new institutions for justice.

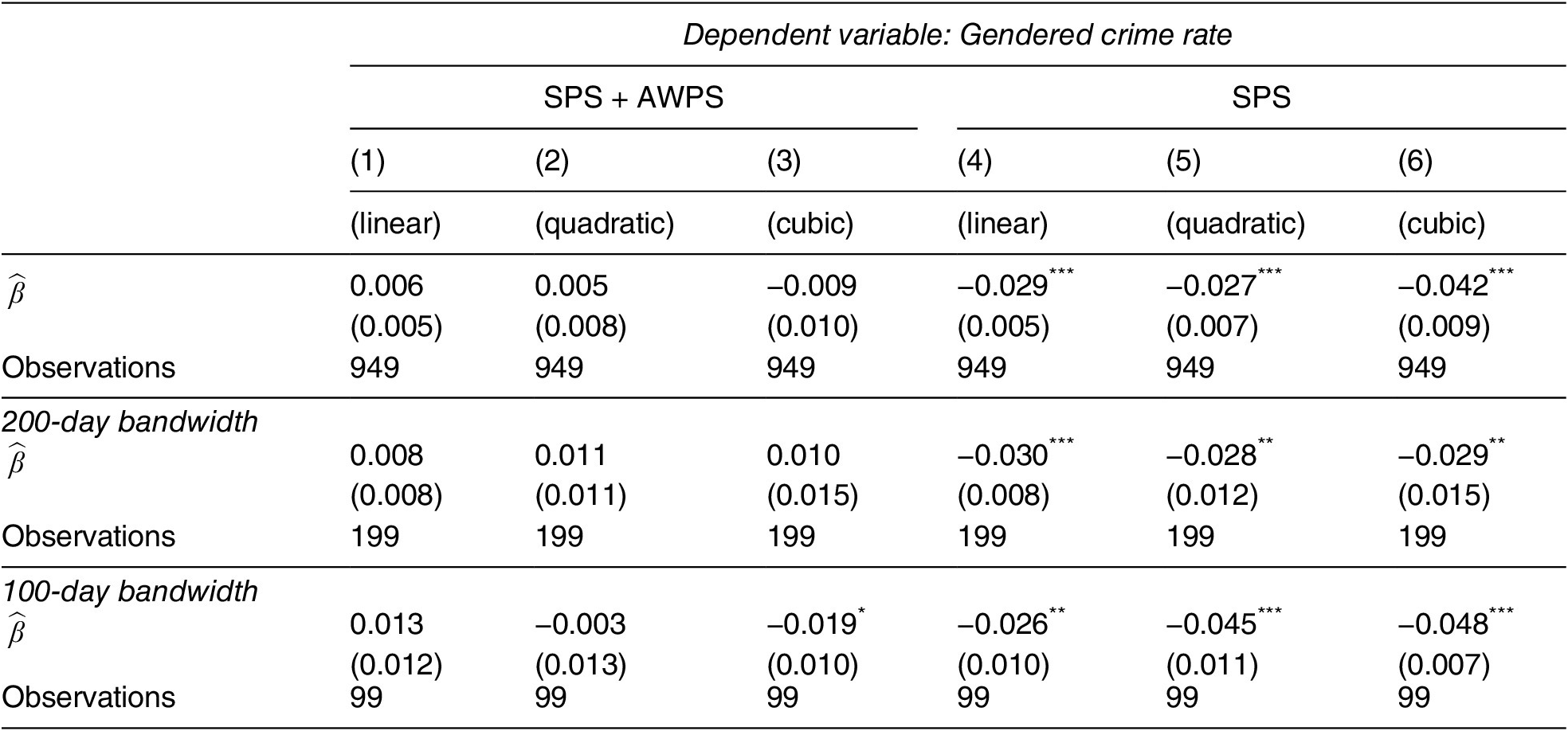

Table 1 presents formal tests across a variety of specifications and bandwidths. Columns 1–3 reveal that all-women stations did not have a positive effect on the rate of gendered crime registered; however, columns 4–6 reveal that the rate of gendered registrations decreased in standard stations between 0.026 to 0.048 (the mean daily rate of gendered crimes registered in the state prior to the intervention was 0.098 per 100,000 citizens). In other words, the registered rate of gendered crimes at standard police stations dropped between 27–49% immediately after the opening of all-women stations.Footnote 17Figure 6 examines heterogeneous treatment effects graphically across individual crimes, and Appendix Tables A4 and A5 present the same in a regression framework; the pattern is consistent across specific crimes. The preintervention mean rates (per 100,000 persons) for dowry, rape, and child sexual assault were 0.038, 0.014, and 0.011; these crimes saw significant declines, by some estimates upwards of half, at standard police stations across the state.

Table 1. Effect of AWPS on Rate of Gendered Crime Registered

Note: SPS and AWPS refer to standard and all-women police stations, respectively. Models in the top row control for year, month, and day of the week. Models in 200- and 100-day bandwidths control for day of the week. HAC standard errors (Newey–West) are in parentheses for all models. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Figure 6. Temporal Change in Individual Gendered Crime Rates Pre/Post AWPS Intervention

Cases Investigated by Female Officers

Even if all-women stations are not associated with an increase in registered crime, enclaves may promote substantive representation by augmenting the influence and participation of female investigators in the force.Footnote 18

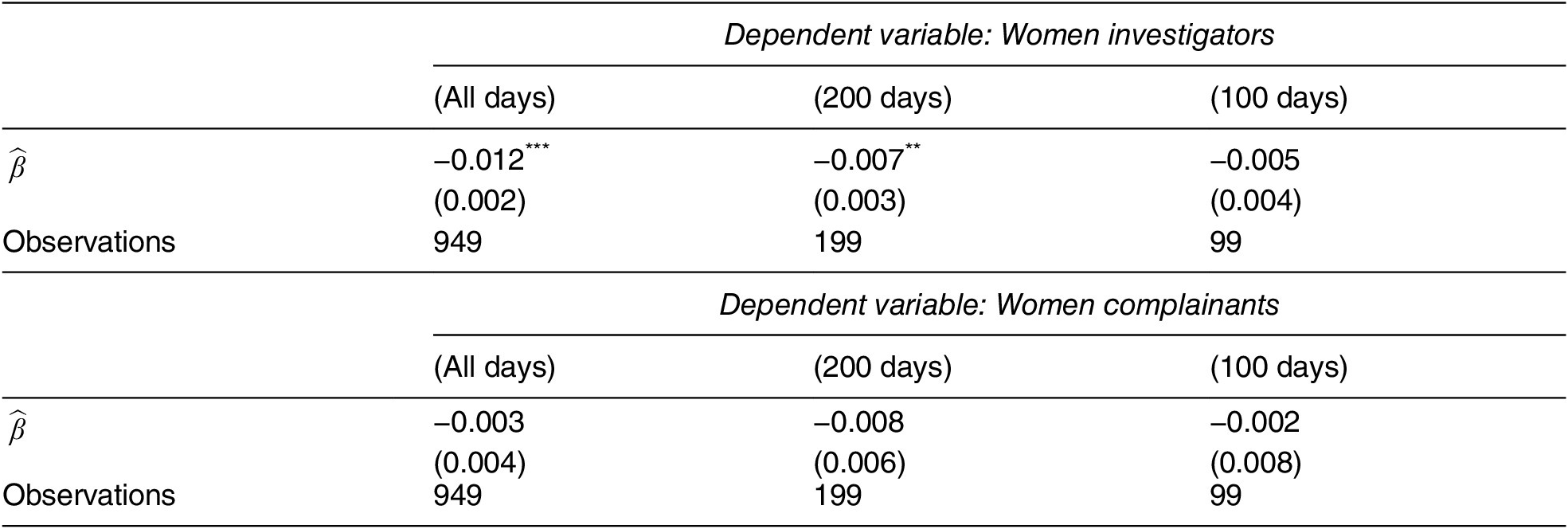

I examine the monthly count as well as proportion of cases that listed a policewoman as an investigating officer before and after the intervention. Strikingly, Figure 7 reveals that from August to September 2015, the absolute number of cases investigated by policewomen precipitously declines. When examining the daily proportion of cases assigned to policewomen, we see that the level declines following the intervention, and it does not fully return to its original level for the two-year duration after.

Figure 7. Responsibilities for Policewomen Pre/Post AWPS Intervention

Why do policewomen get fewer cases after the intervention? Prior to the establishment of enclaves, policewomen—which according to official data accounted for 9% of the force (Appendix Table A20)—were posted at standard police stations where they may have been tasked with a variety of crimes.Footnote 19 However, after the intervention, because female officers were deployed to staff all-women stations and the institutions could only accommodate a specific subset of crimes, female investigators became less likely to carry out diverse forms of police work. In fact, when asked about how all-women stations affect one’s advancement in the police, a policewoman in Uttar Pradesh was upfront and said, “It’s not like this was a request for us. We don’t request postings. The senior SP [superintendent] posted us. I’ve also been the station officer of a normal station. I prefer the gent’s police station. We … can’t handle basic day-to-day cases here.”Footnote 20 Similarly, with an air of disgruntlement, another policewoman said

Murder cases are not investigated at women’s police stations. At the other police station, I was serving in, I was working on a murder case. They [policemen] are now carrying out the investigation while I am posted here. If they ask me to work on it, I will. I recently went to visit a 2-year-old that was raped [and killed] at the hospital/medical college and interrogated the accused. But they [policemen] didn’t end up giving me the case. They are now doing it themselves. So, I said fine, keep doing it! I’ll get other kinds of cases.Footnote 21

While scholars have theorized that all-female enclaves enable women to develop capacity and experience because they are unconstrained by men, this may not be the case with all-women police stations. Assuming upward mobility within an organization is derived from an equitable division of labor where there is no discrepancy between men and women’s work (Babcock et al. Reference Babcock, Recalde, Vesterlund and Weingart2017), gender-based enclaves may promote occupational segregation by hindering female administrators’ potential for professionalization.Footnote 22

Cases With Female Complainants

The establishment of all-women stations could potentially increase comfort with the police among complainants and affect the likelihood that women’s cases are registered, even for non-gendered crimes. I measure the level change in such cases following the intervention; as demonstrated in the second row of Table 2 (or Appendix Figure A9), the proportion of cases (including non-gendered crimes) that had a female complainant did not significantly change following the intervention.

Table 2. Effect of AWPS on Proportion of Cases with Female Complainants and Investigators

Note: The table presents six linear specifications. In the top row, the dependent variable is the daily proportion of cases assigned to women. The second row is the daily proportion of cases in which a female complainant had a case registered (gendered or non-gendered). Models in column 1 control for year, month, and day of the week. Models in columns 2 and 3 control for day of the week. For all models, HAC standard errors (Newey–West) are in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Yet, if the proportion of crimes assigned to policewomen diminishes following the intervention, but cases with female complainants remain stable, then the effect of all-women stations is that policewomen become less likely to accommodate female victims.Footnote 23 In other words, if female complainants sought to be accommodated by policewomen for cases with no gendered subtext close to the crime/incident, this would now become less likely after the intervention. If, however, complainants were also sexually assaulted and visited the all-women station, only then would they likely be assisted by in-group officers. If one of the goals of gender representation is to increase interaction between and responsiveness toward in-groups on the part of administrators (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967), all-women stations may have an adverse effect by associating female officers with gendered crimes only rather than women complainants more generally.

Case Statuses in the Criminal Justice System

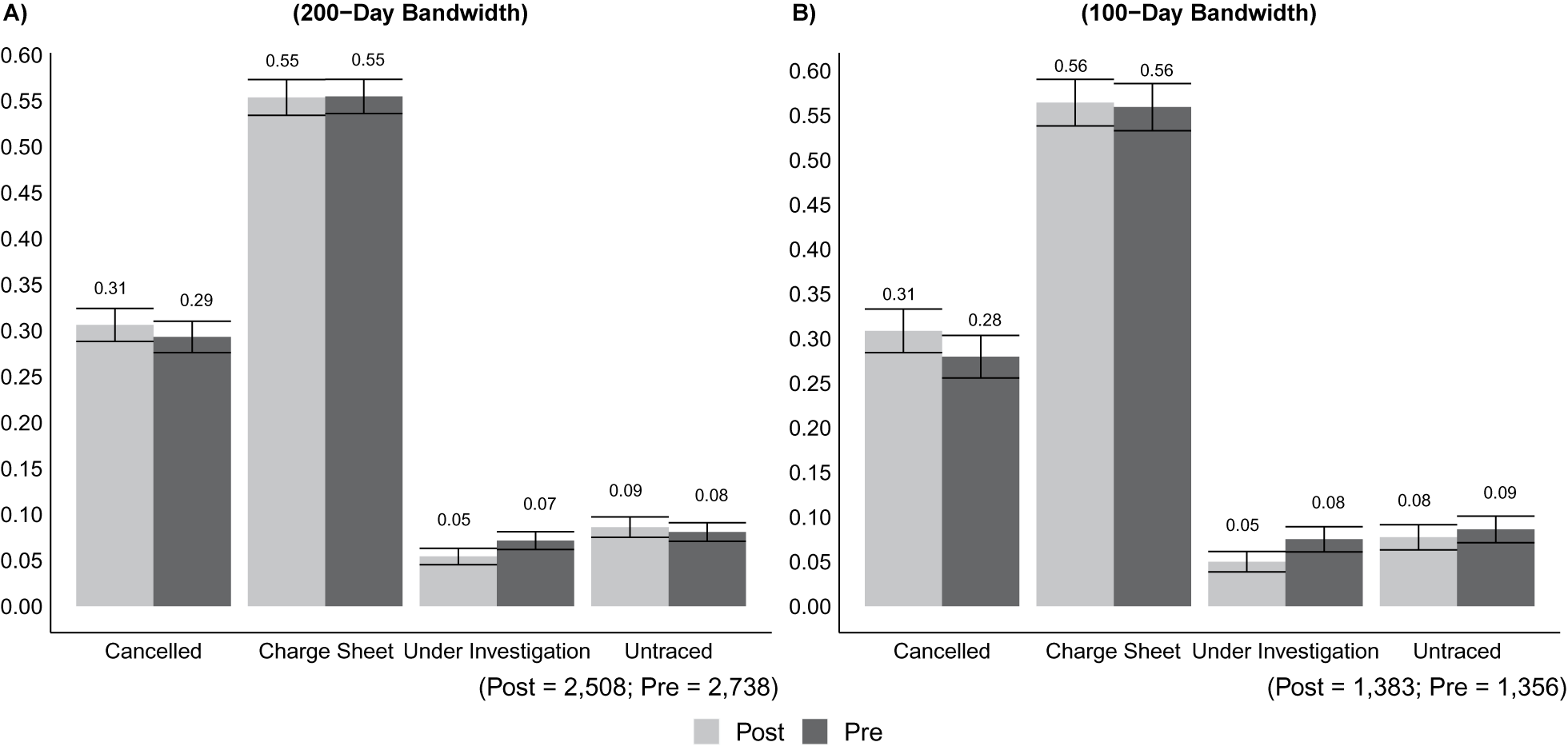

Policewomen in enclaves may be more invested in or concerned about the status of gendered crimes, and they may try to ensure that suspects are charged or cases are sent to the courts once crimes have actually been registered. To investigate this systematically, I merged crime reports with case status records from the Haryana police, which officers update for crimes that they have been tasked with. Most cases (85%) are updated as “chargesheet” or “canceled.”Footnote 24 “Chargesheet” refers to whether an individual has been charged, whereas “canceled” denotes whether a case is believed to be false and therefore not sent to the judiciary.

Figure 8 reveals there is no change in the statuses of gendered crimes in the criminal justice system in 200- and 100-day bandwidths. In fact, there is no substantive change even when factoring in all the days before and after the intervention (Appendix Figure A12). Put differently, even though cases of gender violence at standard police stations were significantly reduced overnight, the expansion of state capacity in the form of additional institutions did not make it more likely that suspects are charged or fewer cases are canceled. Canceled cases typically consist of two categories: (a) cancellations because officers believe the victim is lying, and (b) cases withdrawn by victims, often after pressure from family or the community (Qureshi and Kim Reference Qureshi and Kim2018). As before, approximately 30% of gendered cases were canceled by the police.

Figure 8. Status of Gendered Crimes in Haryana Criminal Justice System Pre/Post AWPS Intervention

Figure 9. All-Women Stations and Perceptions of Policewomen (Female Respondents Across India)

Attitudes Toward Female Officers

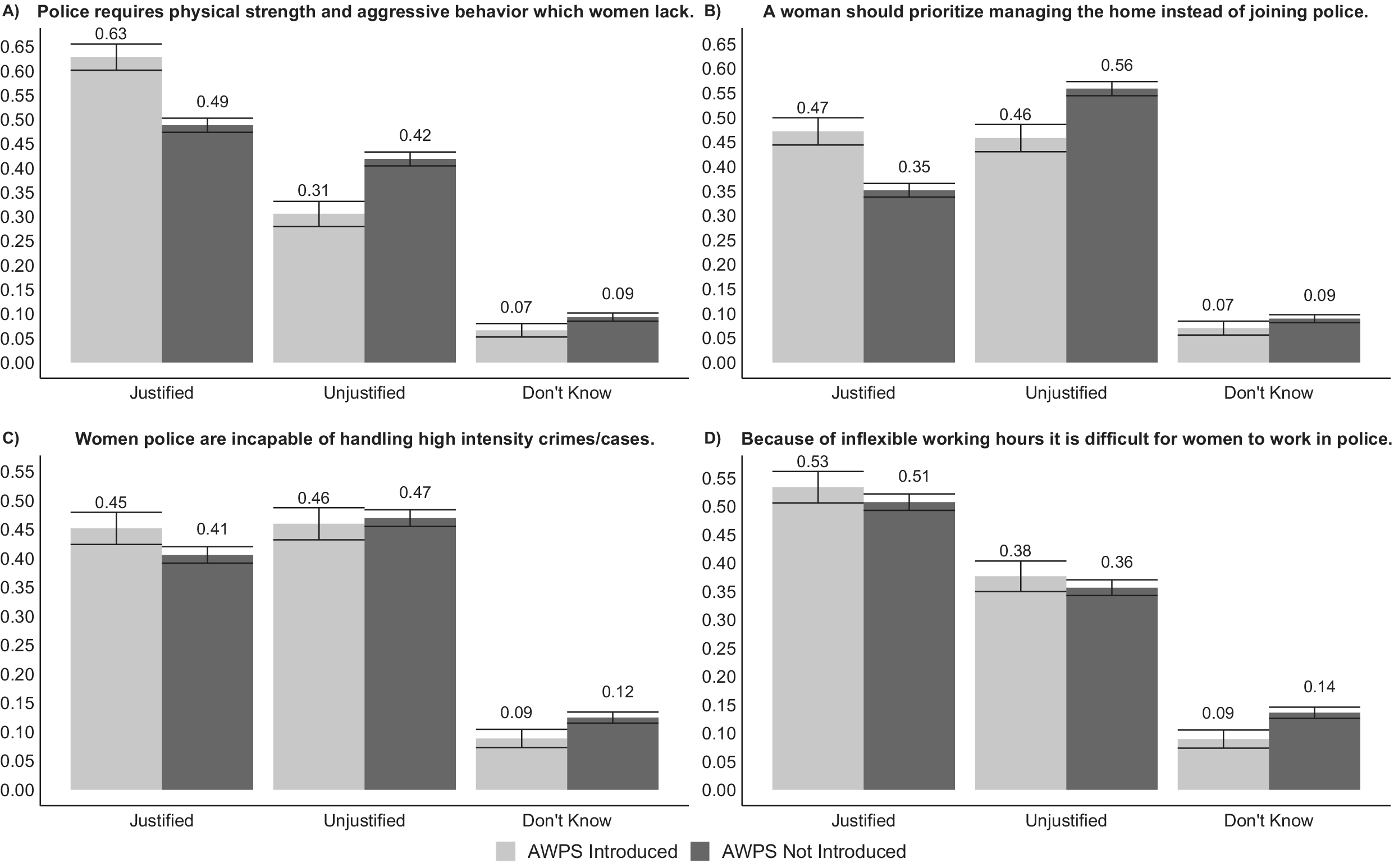

As a final outcome, I examine whether enclaves are associated with positive attitudes toward female officers. I turn to the first nationally representative survey on policing in India, carried out in 2017.Footnote 25 The survey asked respondents about their perceptions of women in the police; respondents were presented with four negative stereotypes and asked to respond on a 4-point Likert-type scale from “very justified” to “very unjustified.” In addition, the survey asked whether an all-women police station had opened in the respondent’s locality.

Descriptively, in Figure 9, when dividing the sample among those that said an all-women station has and has not opened in their area, we find that the institutions are not associated with positive perceptions of policewomen, including among female respondents.Footnote 26 The proportion of female respondents with an all-women station that say the statement in panel A is justified is significantly higher (63%) compared with the justified share without such an institution (49%). Similarly, in panel B, a larger proportion of female respondents (47%) with an all-women station in their locality believe it is justified for women to prioritize managing the home instead of joining the police compared with the justified share among those that say they do not have such an institution (35%).Footnote 27 While one may expect all-women police stations to be correlated with positive perceptions of policewomen, the survey results are suggestive of a null to negative association in attitudes.Footnote 28 Therefore, it is plausible female respondents may not prioritize an all-women station over a standard station; either citizens say they do not have access to an enclave or appear not to have positive perceptions of policewomen in settings where they do.

MECHANISMS

I advance two mechanisms: an institutional and behavioral explanation. Institutionally, I argue that all-women stations caused the decline of gendered crime at standard police stations not necessarily because complainants felt empowered to visit enclaves but because they were told to go there. All-women stations were designed as an alternate mechanism for women to register and have cases investigated; nevertheless, the intervention enabled (male) police officers to lighten their load by forwarding complainants elsewhere.

In addition, from a behavioral standpoint, I find no evidence that officers posted at all-women stations are more likely than policemen at standard police stations to facilitate victims’ access to the formal justice system. Qualitative evidence reveals that policewomen spend time counseling victims at the expense of registration/investigation of cases and may harbor similar biases as policemen.

Bureaucratic Deflection

When asked whether male officers appreciate women working in the police, a female sub-inspector at an all-women station in Uttar Pradesh informed me, “Yes, now more so, because women officers lighten their load. They can focus on other things. [Male] officers can forward complainants to this police station.”Footnote 29 If officers pass on gendered cases when all-women stations are established, then there may be travel costs should victims be turned away from seeking justice at a non-enclave close to their residence or location of crime. Yet, the FIR dataset alone cannot shed light on complainants being sent to another venue because it reflects cases that were formally registered and accommodated by a particular station.

Fortunately, I am able to use another dataset, in particular, information on transferred complainants in Haryana’s neighboring state of Uttar Pradesh. Police stations, as in Haryana, do not always record information on cases that were forwarded, yet Uttar Pradesh—which has housed all-women stations since the 1990s—retains this information in official police logs. The logs reflect (a) cases forwarded to another station at the time a victim attempted to register a crime report and (b) cases transferred midway through investigation.

I use the first set of logs and create two variables: intra- and interdistrict transfers. Intradistrict transfers are those in which an origin and destination police station fall in the same district but the case is moved because the origin station may believe the crime occured in a neighboring precinct. Interdistrict transfers include, say, crimes that occurred on a train or prior to a journey and so are returned to another district.Footnote 30 Typically, in states without all-women stations (e.g., Maharashtra), officers can send complainants away for reasons that relate to territorial jurisdiction.

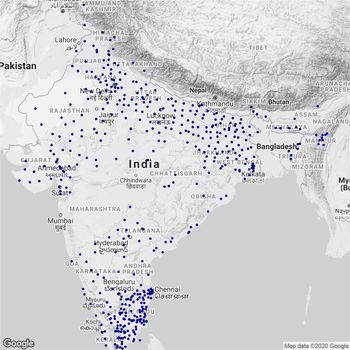

However, in states with all-women stations, officers appear to be able to transfer complainants based on reasons unrelated to territory—that is, the complainant is a woman or the crime is gendered. Indeed, as illustrated by written entries in the log data, officers explicitly provide justifications for transferring a case to all-women stations such as, “The case concerns dowry,” “She mistakenly came to this station,” and “The case concerns a woman” (Table 3).Footnote 31 The logs reveal that in Uttar Pradesh, from 2015–2017, 28% of approximately 8,000 cases forwarded to another police station were to mahila thanas or all-women stations.

Table 3. Selected Entries from the Police Logs (2015–2017)

Note: Cases transferred from one police station to another in Uttar Pradesh. For cases transferred to mahila thanas or all-women police stations, the justifications include, among others, that the “case concerns a woman.”

I geocode each police station that both transferred and received cases in Figure 10. The plot is illustrative of two points. First, all-women stations were the destination of the largest number of transferred complainants in Uttar Pradesh. As the sizes of the red circles reveal, the top 20 of approximately 1,100 police stations across the state that had crimes transferred to them happened to be the all-women stations. Second, the figure displays where the transferred cases originated from; most crimes forwarded to an enclave were done so by surrounding non-enclaves in the district.

Figure 10. Stations Complainants Forwarded to (Uttar Pradesh)

I calculate the geodesic distance using the longitude/latitude of the origin and destination police stations. Each dot in Figure 11—representing a real individual who came forward for help to a police station but was forwarded elsewhere—is plotted by the distance in kilometers complainants were now forced to travel. The distance women must travel (if traveling in a straight line) to an all-women station—not taking into account quality of roads and other factors—is 20 km (1st Quartile = 5, Median = 17, 3rd Quartile = 30) or twice as long for other generic transfers related to territorial jurisdiction.Footnote 32 It is unclear how many complainants actually followed through and traveled to the other sites for justice.

Figure 11. Distance Citizens Must Travel When Forwarded (Kilometers)

It may be that (male) officers do not deflect cases for malign reasons but believe a victim may actually receive better service and representation at an all-women station. Still, Indian law was amended in 2013 after a brutal gang-rape of a college student on a moving bus; it mandated that crimes brought forward at police stations have to be accommodated, especially gendered crimes, which are all “cognizable.” Furthermore, while the law outlines a policewoman should, if possible, be present for the recording of a female victim’s complaint (GOI 2013), there is no formal rule that female officers must investigate all gendered crimes, or those with a female complainant, or even that women complainants be sent elsewhere if no policewoman is present at a non-enclave.

Reconciliation and Counseling

A mechanism that may explain why the intervention is not associated with an aggregate change in registered crime is that all-women stations emphasize counseling whereby policewomen “patch up” female victims with abusers. Because police officers do not record data on victims that were dissuaded from registering a case, I carried out ethnographic research at all-women stations in Haryana, and eight such institutions in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.Footnote 33 Policewomen repeatedly underscored how they were unlikely to register cases because they believed (a) “patching up” a woman with her abuser was more effective than registration of cases and (b) formal action taken in cases of gendered crimes may embolden women to bring frivolous cases or weaken the victim’s social standing in the community. Qualitative research suggests that complaints that officers at standard stations deflected were essentially being “counseled” at all-women stations such that, at either venue, it was only the most brutal cases that were registered. Moreover, inside enclaves, policewomen expressed dissatisfaction that they were not working on diverse cases, and victims often appeared distressed that their cases were not being registered after seemingly repeated attempts to do so.

Officers at all-women stations often dissuade victims from accessing the criminal justice system—especially in cases where they are being raped or tortured by their husbands—and signal the virtue of family.Footnote 34 One policewoman said

The main piece of advice we give [the victim] is to stay in the family. In case there is a problem or some sickness, you need the support of your family… . Sometimes the advice we have given has certainly saved marriages. If the marriage is saved, then we certainly get satisfaction [emphasis added].Footnote 35

When asked if an emphasis on “mediation” rather than arrest might enable the violence to continue, another policewoman said

We make sure he [the suspect] asks for forgiveness and tries to sort it out. If the girl has no family and we find that she’s living with her husband and his family and there’s a good deal of torture going on, then we may register a case [emphasis added]. But there’s often a settlement of the situation and everyone leaves satisfied [emphasis added].Footnote 36

The empirical findings in this article show that 30% of gender violence cases are canceled by the police because officers may believe women are exaggerating. Qualitative insights suggest policewomen are likely to hold similar beliefs as policemen. For instance, when I asked a policewoman who served as a computer operator in Kaithal, Haryana about the kinds of cases that come forward in enclaves, she noted that victims fabricate stories. She said

Most of the cases get patched up here. Of the cases that come here, only about 50% go to court… . In my point of view, 70% of the cases are lies. The truth is something else, and what the women try to have written down is something else. Most of the cases that come here women say, “look, I was beaten up.” But that happens in everyone’s house, I’m from a village too.Footnote 37

In fact, some senior bureaucrats expressed skepticism about enclaves. A veteran policewoman and administrator who previously oversaw dozens of local police stations said

If I am in trouble, I will go to a police station that is nearby. Yet, the normal thana may send me to the all-women station 13 kilometers away. If I am in distress, why should I be asked to go farther away? We should have women stationed in normal police stations rather than all-women police stations. What’s worse is that the officers at all-women police stations spend a lot of time counseling. I don’t know whether it’s “counseling” or not, because they are not trained counselors. If, in front of police, you can make a compromise with an abuser, the police officers think it is a success… . Sometimes when a female sub-inspector decides not to register a crime, in her own way she may be trying to be helpful. In India, marriage is still so sacrosanct, it pains everyone to break it. Once you don a uniform, your thinking and cultural background is still the same. So, people may act in a certain way without bad intentions.Footnote 38

DISCUSSION

I examine the introduction of an institutional design in a developing country where law enforcement suffers from low levels of legitimacy, especially among women. I ask, can gender-based enclaves facilitate representation for women in the police and increase victims’ formal access to justice? In addition to making a distinction between “enclave” and “inclusive” representation, I introduce a new dataset of crime, while also employing a large-scale survey, official police logs, and eight months of field research in north India. Taken together, I argue that enclaves or representation as separation may have unintended consequences.

In two of India’s largest states (Bihar and Uttar Pradesh), all-women stations account for a low level of registered crime. In the state of Haryana, I leverage a discontinuity whereby the government opened all-women stations at exactly the same time in order to coincide with a festival. I demonstrate that while the number of cases in Haryana’s more recent all-women stations are greater than other states, the aggregate level of registration remained stable following the intervention.

Strikingly, female-only stations served to significantly lighten the load of standard stations, despite the fact that they were meant to be an alternative forum rather than an exclusive venue for women to access services. In settings where there are few police officers per capita, overstretched and underresourced law enforcement agencies may use any incentive to deflect cases. In this way, the creation of enclaves may have created red tape, thereby serving a function similar to Women’s Bureaus of early twentieth century America in terms of keeping gendered crimes outside of “mainstream” police work. Using official logs from Uttar Pradesh, I show officers explicitly note down that they transferred complainants simply because the victims were women. Regardless of whether (male) officers pass on cases for malign reasons (shirking) or in a benign effort to alert complainants to an alternate venue with a sincere belief that specialized institutions will better represent or prioritize women’s preferences, I show that the act of forwarding complainants adds travel (and likely other) costs. This may induce victims to reconsider registering a case at all, many of whom turn to the police as a last resort.

Further, the intervention is not associated with a change in services—that is, more suspects charged or fewer cases dismissed. Qualitative evidence suggests that when women do in fact come forward to register cases at all-women stations, they are likely to be counseled or “patched up,” especially for crimes in which the victim and abuser are known to one another. This suggests that the mere separation of female officers in group-specific institutions might not automatically change outcomes vis-à-vis the criminal justice system, and it may even hinder case registration and formal investigation by heightening discourse inside police stations about the virtue of family or one’s social status. Survey evidence reinforces the notion that all-women police stations may not be associated with positive perceptions of policewomen.

Counterintuitively, while the expansion of state capacity in the form of new police stations run by policewomen should theoretically have increased the influence of and responsibilities for female officers, the intervention reduced their registered caseload, relegating policewomen to tasks the state believes they would be suited for because of their gender. This may be counterproductive for two reasons. First, experimental evidence from India shows women have the most trust in policewomen when they are investigating gender-neutral rather than gendered crimes (Jassal and Barnhardt Reference Jassal and Barnhardt2020). Second, female officers working in collaborative environments sensitize policemen to gender biases (Miller and Segal Reference Miller and Segal2019), yet, if policewomen are physically and occupationally segregated in enclaves, patriarchal norms may remain unchanged.

While enabling lawmakers to signal progressive change, enclaves may have consequences that are reinforced in conservative social settings where deep-rooted beliefs predominate about gender violence being a “family matter” or such cases not being on the same par as other crimes (Qureshi et al. Reference Qureshi, Kulig, Cullen and Fisher2020). We may see different effects if, for instance, all-women police stations are designed to investigate all forms of crime, or potentially in settings with dissimilar bureaucratic arrangements or gender norms (Perova and Reynolds Reference Perova and Reynolds2017). Still, from a policy perspective, the results suggest that gender sensitization of serving officers or “inclusive” representation in the form of hiring more women to work within existing bodies alongside men may be alternatives to “enclave” representation. Furthermore, while gender diversity in public institutions and increased access points for services are essential, a more comprehensive approach may be needed toward addressing the scourge of violence against women.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000684.

Replication files are available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VRH8ND.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.