INTRODUCTION

It is easy to see how the commands as well as the questions of Congress may be evaded, if not directly disobeyed, by the executive agents. Its Committees may command, but they cannot superintend the execution of their commands. (Wilson Reference Wilson1885, 271)

Although Congress possesses the Constitutional authority to create and fund government operations, its ability to motivate effective implementation of law by the executive agencies it empowers to do so is circumscribed by informational and contractual challenges. Relative to the executive branch, members of Congress have less expertise and less easy access to policy information, making it difficult to evaluate bureaucratic performance. Even when members have sufficient expertise and information to believe an executive agency is underperforming, civil service protections and separation of powers make it difficult for the legislature to direct the actions taken by employees of the executive branch. Members of Congress may command, but they cannot superintend execution of those commands.

A long literature in political science explores the many ways that legislatures work within these challenges. While some scholars conclude the legislature is on balance successful in controlling bureaucratic behavior and inducing efficient production of public policy (e.g., Weingast and Moran Reference Weingast and Moran1983; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987; McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984) others suggest the legislature’s influence is likely weak (e.g., Moe Reference Moe1987; Wilson Reference Wilson1885). This debate remains unresolved after decades of research.

Among the tools used to identify and remedy bureaucratic underperformance, scholars commonly consider legislative oversight. Oversight hearings, in particular, have been recognized as a process through which members of Congress collect information on bureaucratic efforts, highlight shortcomings, and use the implied threat of future budgetary or statutory restrictions to motivate bureaucratic response to congressional goals.

Almost all empirical work in political science measures the presence of oversight action—when and how Congress conducts oversight—but stops at the question of if oversight works and how much oversight activity influences agency behavior. We know a fair amount about when Congress performs oversight, what happens in oversight hearings, and how the distribution of oversight authority across committees affects perceptions of Congress’s effectiveness in conducting oversight. Yet we know almost nothing about how effective these efforts are in constraining and superintending agency behavior—the efficacy of oversight.

We argue that this hole in our understanding is due to the inherent difficulty in evaluating the performance of the federal bureaucracy. Because executive agencies often produce public goods that, by definition, are difficult to price through market mechanisms, it is hard to evaluate how effectively the bureaucracy delivers on the directives set by congressional statute. For example, is a cost of $78 million per F-35 strike aircraft (Government Accountability Office 2022) evidence of effective or ineffective legislative oversight of the defense bureaucracy?

To estimate the effectiveness of congressional oversight, one would want measures of the goals of Congress and the output of the bureaucracy on a common scale, ideally comparable across agencies and over time. Comparison of the goals of Congress and the output of the bureaucracy on such a scale would provide evidence on the magnitude of control. A comparable measure is not an easy task because agencies implement a range of programs that tackle diverse sets of issues with varied mandates, constraints, and institutional settings. Indeed, scholars of the bureaucracy have suggested that lack of a comparable measure of agency and program outcomes is one of the chief obstacles in the study of bureaucratic politics. David Lewis (Reference Lewis2007, 1075) writes, “One major difficulty is that it is hard to define good performance objectively and in a manner acceptable to different stakeholders.” One approach has been to use questions on program performance asked in surveys of federal bureaucrats (e.g., Clinton, Lewis, and Selin Reference Clinton, Lewis and Selin2014; Gilmour and Lewis Reference Gilmour and Lewis2006; Lewis Reference Lewis2007), but these measures are limited in availability across time and might differ in application or measurement across programs and individual respondents.

Here, we create a new dataset matching congressional oversight activity to a plausibly comparable measure of bureaucratic performance to estimate the efficacy of congressional oversight. Since the early 2000s, Congress has sought to reduce improper payments made by bureaucracies to contractors and clients. An improper payment is “any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirement” (Paymentaccuracy.gov 2023). Improper payments are identified by ex post audits of disbursements to determine propriety—that is, sampling from the previous year’s payment database and determining the propriety of each sampled payment. Examples of improper payments include Medicare coverage of beneficiary goods (e.g., powered wheelchairs) without adequate prior authorization, Medicare payments for services determined in a subsequent audit not medically necessary, Medicaid payments to providers ineligible due to suspended or revoked licenses, Internal Revenue Service tax refunds paid without following required procedures to review W-2 and other documentation, Department of Homeland Security bills paid to a contractor for services beyond those authorized by statute, or Department of Labor unemployment benefits to a fraudulent recipient.

According to the Government Accountability Office [GAO] (2023, 15), the main causes of improper payments are failure to access the information to properly document and disburse the payment, inability to access, or nonexistence of, information needed to follow statute, or lack of documentation from applicants to determine payment eligibility. These problems mix employee behavior, accounting systems, information technology, and contractor or applicant actions (including fraud).

Improper payments are a large bureaucratic deficiency—totaling $247 billion in fiscal year 2022 and more than $2.4 trillion since 2003—that have been a recurring target of oversight, executive directives, and statutes from members of both political parties.

Improper payments can be made by any agency or program in any fiscal year. Because both improper payments and agency outlays are measured in dollars, the fraction of all payments improper (the “improper payment rate”) provides a plausibly comparable over-time and cross-agency measure of agency performance. Unlike many other outputs of the bureaucracy, there is near-universal agreement on what Congress desires from the bureaucracy: fewer improper payments. Members from both political parties have passed five federal statutes, held scores of hearings, and referred to improper payments in dozens of appropriation committee reports.

The improper payment measure allows us to set aside bureaucratic policies where members of the legislature have different priorities, which complicates evaluation of legislative control, and instead focus on a valence issue with objective measures of what would (and would not) follow from effective control. Congress wants fewer improper payments and, so, effective legislative control implies lower rates of improper payments.

We compile new data on the fiscal year rates of improper payments at the agency and program level and compare changes in this measure to new measures of the incidence of oversight on improper payments. We first examine the effect of congressional hearings, a keystone of legislative oversight. If oversight is effective in mitigating agency loss, we should observe that hearings lead to a decline in improper payment rates. If, on the other hand, the power of the legislative branch to motivate action in the executive is weak, we would not see such a decline. Congress has used oversight hearings in attempts to reduce levels and rates of improper payments for more than two decades, providing a unique opportunity to study the influence of congressional oversight on a quantitative and comparable measure of executive branch effort and output.

We imagine oversight as a two-way informational exchange between the legislature and the agency. The bureaucracy has many activities directed by enacted statutes but does not have the resources to pursue all to full effort. Executive agencies must make choices about what to prioritize given finite budgets. Oversight communication allows members of Congress to express their priorities about allocation of bureaucratic effort. Our read of hearing transcripts about improper payments and our interviews with congressional committee staffers are consistent with this interpretation. Members query officials about the actions they are taking and plan to take to combat improper payments and about what resources might help them be more effective. Officials learn about legislative priorities from member statements and questions. Our research question, then, is what consequences these interbranch exchanges have on bureaucratic performance.

The threat of oversight, of course, exists even when Congress is not actively holding an oversight hearing. Absent a specific action of oversight—hearing, correspondence, subpoena, etc.—agencies are still aware that Congress could execute oversight and then could take remedial action. We measure here the effect of Congress’s communication of priorities to agencies through oversight beyond any effect of the general regime of legislative oversight, that is, the marginal effect of additional communication of priorities. This view of oversight as the transmission of directives and priorities from Congress to agencies echoes the focus of the empirical oversight literature (e.g., MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016) and also reflects what legislative committee oversight staff reported to us when we interviewed them about oversight.

Should we expect oversight to motivate action within the bureaucracy? On the one hand, information that Congress receives through oversight activities can be used when Congress decides on program authorizations, budgets, or future policy proposals, possibly inducing agencies to respond to oversight. Scholarship suggests that other forms of nonstatutory control influence bureaucratic behavior (Acs Reference Acs2019; Bolton Reference Bolton2022); oversight activities might similarly spur bureaucratic response. On the other hand, simply revealing information about an agency’s performance does not, in isolation, require agencies to take action. The efficacy of oversight stems from the public revelation of agency performance and the implicit threat that Congress, in gaining this information, is watching the agency and might take future action. This limitation to oversight may thus narrow its effectiveness in influencing agency behavior (as argued by, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1885; Moe Reference Moe1987).

Oversight could even appear to have consequences opposite the desired effect. Change in agency performance may first require additional bureaucratic attention to the problem and time to implement reforms. If efficacy of oversight stems from the attention it induces executive agents to produce, hearings held on improper payments may lead to a near-term increase in rates as the targeted agency increases staff time devoted to improper payments and discovers previously unappreciated errors in its payment portfolio.

We offer two main results. First, we find that congressional hearings do lead to subsequent declines in improper payments. When a congressional committee calls a witness from the bureaucracy to testify about improper payments, on average the rate of improper payments for that witness’s agency declines in subsequent fiscal years.

Second, while there is downward movement in rates following oversight, the magnitude of these declines is small relative to the scope of the problem. This is most clear when looking at the pattern of improper payments across the entire bureaucratic state, which, despite decades of hearings and statutory reforms by Congress (along with attention from the executive), has shown little improvement. Mean improper payment rate estimates of programs directed to audit payments were 4.0% in 2005 and 5.9% in 2021. Congressional statute defines a 1.5% improper payment rate as “significant” and the Office of Management and Budget has pointed to a 1% annual decrease in the improper payment rate of a specific program as a successful reduction.Footnote 1 Our estimates of the average effect of oversight hearings are an order of a magnitude smaller.

An additional result of our analysis is that program estimates of improper payments appear to increase in the fiscal year of the oversight hearing. At first glance, this suggests that oversight has a counterproductive effect of increasing the problem that Congress sought to address through oversight. However, our reading of hearing transcripts suggests that this near-term increase is likely driven by agency officials increasing efforts to identify and measure improper payments following the hearing. This apparent increase in agency loss is more likely a more accurate measure of the true rate than an actual increase. Declines in fiscal years beyond the first support this interpretation.

To account for the possibility that the legislature also engages in oversight outside of formal hearings (e.g., Selin and Moore Reference Selin and Moore2023), we consider other techniques of oversight. We rule out a possible secondary channel of oversight, correspondence between individual legislators and agencies. We find that agency payments are rarely mentioned in these contacts, which Lowande (Reference Lowande2018) finds to be largely driven by issues that have direct constituent or district interests. We also place the effectiveness of oversight hearings into the larger context of other actions taken by Congress and the president on improper payments. We evaluate the efficacy of appropriation committee reports, statutes, and executive actions on improper payments and find muted idiosyncratic effects that do not contain the systematic pattern seen with oversight hearings.

One immediate concern with our design is that witnesses at oversight hearings are not invited to testify at random. Instead, congressional committees might be selecting agencies or programs for oversight because of issues with payment integrity. Although we cannot entirely rule out this concern, we offer two counterarguments. First, we plot prehearing trends in improper payments and use regressions to try to predict incidence of hearings. Neither analysis suggests a relationship between prehearing changes in improper payments and hearings. Second, agencies count improper payments in the fiscal year after disbursement, at earliest, by sampling from the previous year’s accounting database. This means that by the time Congress learns of rates and holds a hearing, the payment procedures of the agency might well have changed. The use of random samples also induces sampling variability into the process, further limiting tight endogeneity. To our read, these factors make a strong selection effect unlikely.

Our results suggest that congressional oversight is of limited effectiveness. Discussion of oversight is frequently linked with other action that a legislature can take to influence the bureaucracy: statutory actions such as determining agency budgets, the amount of discretion granted to bureaucrats (e.g., Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994), and splitting authority across multiple agencies (Bils Reference Bils2020), or nonstatutory actions such as specifying directives in committee reports (Bolton Reference Bolton2022) or communicating the preferences of legislative actors (Lowande Reference Lowande2018; Shipan Reference Shipan2004). In the realm of improper payments, however, Congress has availed itself of many of these additional tools yet improper payments remain an as-yet unsolved problem across the bureaucracy. Our unique measure of effectiveness, thus, allows us the conclusion that Congress’s prospects for control of the modern bureaucracy are in doubt.

LEGISLATIVE EFFORTS TO CONTROL THE BUREAUCRACY

Scholars disagree about the ability of Congress to control the bureaucracy. On the strong control side of the argument, the literature suggests that ex post and ex ante tools allow Congress to influence bureaucratic action. Scholars of the “congressional dominance” theories argued Congress has at its disposal myriad ways to influence agencies including ex post tools such as oversight and budgetary decision making (McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Weingast Reference Weingast1984; Weingast and Moran Reference Weingast and Moran1983) and ex ante tools such as design and use of administrative procedures (McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987; Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989) or design of delegation and discretion (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994; Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999).

On the other side of the argument, critics such as Moe (Reference Moe1987) argue that theories of strong congressional control neglect the motivations, resources, and incentives of the bureaucracy, which might lead the bureaucracy to ignore or sidestep congressional wishes. Even with control mechanisms such as oversight, appointments, budgets, or new legislation, bureaucrats still possess their own autonomy such that Congress fails to achieve political control. Moe (Reference Moe1987) argues about congressional dominance theory, “While the theory presumes to explain congressional control of the bureaucracy, in fact it offers little more than an assertion supported by reference to legislative rewards and sanctions and their alleged efficacy in securing bureaucratic compliance” (480).

Scholars have devoted much empirical effort to evaluating ex ante control of the bureaucracy. For example, studies have shown how legislatures can vary influence over agency outcomes through the use of administrative procedures such as the notice and comment process in rulemaking (e.g., Balla Reference Balla1998; Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2010; Reference Yackee and Yackee2016), the appointment of agency personnel (e.g., Lewis Reference Lewis2007; Moe Reference Moe1985; Wood and Waterman Reference Wood and Waterman1993), the level of discretion given to agencies when writing statutes (e.g., Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002), or through the internal organization of Congress and committee jurisdictions (e.g., Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990; Arnold Reference Arnold1979; Bendor Reference Bendor1985; Clinton, Lewis, and Selin Reference Clinton, Lewis and Selin2014; Dodd and Schott Reference Dodd and Schott1979; King Reference King1997). These studies position themselves to empirically evaluate the extent to which the legislature can command ex ante influence over the bureaucracy.

Among ex post means of legislative control, oversight is commonly highlighted as a central mechanism available to Congress to influence the bureaucracy. Conceptually, McCubbins and Schwartz (Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984) define oversight as the way in which Congress seeks to “detect and remedy executive-branch violations of legislative goals.” They argue that a reelection-minded Congress prefers “fire alarm” oversight, with tools and procedures designed to alert Congress to violations that are most salient to interest groups and constituents, rather than “police patrol” oversight that calls for comprehensive, centralized monitoring. This view places Congress as engaging in oversight of the executive branch primarily to fulfill political goals, echoing other work where oversight is viewed as an activity used in legislators’ pursuit of reelection (Fenno Reference Fenno1973; Ogul Reference Ogul1976).

Others step back from elections and suggest oversight helps stop “policy drift,” where oversight occurs when agencies take actions inconsistent with Congress’s policy goals (Dodd and Schott Reference Dodd and Schott1979; Kriner and Schwartz Reference Kriner and Schwartz2008; McGrath Reference McGrath2013). While policy goals are, of course, related to political goals, it remains unclear whether oversight is primarily driven by reelection motives or policy concerns.

Empirical work on oversight has largely focused on examining congressional committee hearings where the number (or presence of) oversight hearings conducted by congressional committees is used to measure oversight (e.g., Fowler Reference Fowler2015). Scholars have found that congressional oversight activity has overall increased over time (Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990; MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016), is driven by disagreement between congressional committees and the bureaucracy (Kriner and Schwartz Reference Kriner and Schwartz2008; McGrath Reference McGrath2013), and is more frequent during periods of divided government (Kriner and Schickler Reference Kriner and Schickler2016) or periods just after unified government is reestablished as committees engage in “retrospective” oversight (MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016).

Congressional efforts at oversight are not limited to committee hearings. Congress conducts oversight through correspondence between legislators and bureaucrats (Lowande Reference Lowande2018; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2018) and congressional participation in rulemaking (Lowande and Potter Reference Lowande and Potter2021; Silfa Reference SilfaN.d.). Scholars have found that these interactions between legislators and bureaucrats are generally driven by constituency or district concerns rather than ideological patterns.

While these empirical studies have explained when and why Congress is likely to engage in oversight activities, they all stop at the point of oversight being conducted. While such analysis answers some important questions (e.g., if Congress engages in oversight when it is called for, as in McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984 or MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016), it does not answer a question of central importance to our models of legislative control for the key ex post mechanism: How much does congressional oversight influence bureaucratic behavior? Much work on oversight assumes that it influences bureaucratic behavior and thus helps resolve Congress’s principal–agent problems vis-à-vis the bureaucracy. But, to date, we do not know how accurate this assumption is and, therefore, how well oversight facilitates congressional control.

Research has circled the efficacy of oversight. Kriner and Schickler (Reference Kriner and Schickler2016) find that congressional oversight hearings can erode presidential approval ratings, giving presidents the incentive to change bureaucratic behavior. Oversight hearings also occur more often when they are most likely to have a policy effect (MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016), implying that the purpose of hearings is to influence bureaucratic action. Studies of other nonstatutory means of control have found effects on bureaucratic behavior, such as agencies withdrawing policy proposals in response to the possibility of a legislative veto (Acs Reference Acs2019) or agencies adjusting their own monitoring activities in response to shifting preferences of committees and Congress (Shipan Reference Shipan2004). But no work, to the best of our knowledge, directly estimates the empirical relationship between oversight hearings and magnitude of change in congressional agency loss to the bureaucracy.

One concern about oversight hearings as a method of congressional control is that they may be subject to forces unrelated to the putative goals of the oversight. Due to their public nature, the existence of a hearing or the content of the hearing itself may reflect ideological or partisan disagreement, reducing its potential effectiveness for true oversight. For instance, the House Select Committee on Benghazi oversight hearings, while ostensibly on the topic of conducting oversight and investigations into the attack on the U.S. consulate in Libya, were commonly interpreted as an effort to discredit Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as she pursued election to the presidency.

While oversight hearings in general can indeed be motivated by factors unrelated to the topic of the hearing—thus influencing the content of the hearing and potentially its effect on the bureaucracy—improper payments are, for better or worse, a topic that does not garner much publicity, political grandstanding, or partisan disagreement. As we show in the next section, reducing improper payments has been a goal of members and presidents of both parties, suggesting against oversight hearings on improper payments as political grandstanding.

IMPROPER PAYMENTS AT FEDERAL BUREAUCRACIES

In order to measure the effectiveness of oversight, we require a measure of bureaucratic outcomes such that we can estimate the outcome with and without (or, before and after) oversight. This requirement is difficult to meet due to the nature of public policy. Government bureaucracies often produce public goods, which by their nature are difficult to value on some common scale and therefore difficult to compare across time and agencies.

We have identified one measure of bureaucratic outcomes that is, at least to first approximation, comparable across time and agencies. Improper payments are “any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirement” (Paymentaccuracy.gov 2023). Payments made by the bureaucracy are denominated in dollars. Rate of improper payments made by federal agencies is a fraction that can be compared within agencies over time or between agencies. Below, we briefly summarize actions the federal government attempted to reduce improper payments. This history reveals that a bipartisan over-time consensus exists that the rate of improper payment should be reduced and that oversight should be one tool to do so.

Both Congress and the executive have worked to rein in improper payments made by federal bureaucracies for almost 25 years. In 2022, Gerald E. Connolly, Chair of the Subcommittee on Government Operations, opened a hearing on improper payments emphasizing continued prioritization by committees and Congress as a whole, the ongoing challenge, and the bipartisan nature of the goal (in referencing a former chair of the opposite party):

Connolly: This is a subject of this subcommittee going way back. In fact, one of my first hearings, I remember, was with a former chair of this subcommittee, Todd Platts, talking about improper payments almost 14 years ago… Though improper payments have been a priority of Congress since the beginning of the 21st century, they remain high and they continue to grow…. (Committee on Oversight and Accountability 2022)

Improper payments rose to the congressional agenda after the Government Management Reform Act of 1994 required major departments to prepare and have audited agencywide financial statements (Government Accountability Office 1999, 5). When it reviewed nine audits from fiscal year 1998, the GAO identified $19.1 billion in improper payments and concluded, “Improper payments are much greater than have been disclosed” (6). GAO made recommendations to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to improve internal controls and reduce improper payments.

The Senate held one hearing on improper payments in fiscal year 2000 with witnesses from the GAO and USAID. Congress’s first statutory effort came with its August 2001 markup of H.R. 2586, the Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2002. The House Armed Services Committee inserted the “Erroneous Payments Recovery Act of 2001” to the thousand-plus page bill. Sections 812 and 813 directed executive agencies with contracts of total value greater than $500 million to conduct programs to identify and then recover erroneous payments made to federal contractors. Agencies would develop their own programs following guidelines to be created by OMB. The bill passed the House and went to conference with a Senate version without the provision. The conference report included the provision and became Public Law 107-107 with the signature of President George W. Bush on December 28, 2001.

The Improper Payments Information Act of 2002, signed into law November 26, 2002, provided further and more extensive guidance than the 2001 statute. The new law directed any executive program with estimated improper payments exceeding $10 million to audit and estimate improper payments, report on causes, state what infrastructure or information technology requirements would help reduce improper payments, and describe what steps had been taken to reduce such payments.

OMB issued guidance for agency implementation of the 2001 and 2002 laws in January and May of 2003 (OMB memoranda M-03-07 and M-03-13). OMB directed agencies to collect statistically valid samples of payments to estimate improper payment rates and report on the results to OMB and Congress effective fiscal year 2004. In a 2006 memorandum, OMB director Rob Portman updated and consolidated guidelines, allowing “low-risk” programs to audit payments once every 3 years rather than annually. High-risk programs would continue to implement annual audits and annual reports on efforts for remediation.

During the decade of the 2000s, Congress increased oversight on improper payments. The House and Senate held a total of 13 hearings from fiscal 2003 to fiscal 2009.

On November 20, 2009, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order (EO) 13520 “Reducing Improper Payments.” The EO directed implementation of new executive actions more punitive than previous OMB guidance. Agencies would have to publish annual information about improper payments, identify by name an agency official accountable for improper payments, and coordinate with other agencies to identify contractors and practices related to high improper payment rates.

OMB Memorandum M-10-13 implemented EO 13520 directives on March 22, 2010. Agencies would each have an “accountable official” to oversee and take responsibility for improper payments and who would issue an annual report to the agency’s inspector general (IG). Programs would also have to publish target reductions in improper payment rates and publish the names of contractors who received improper payments but failed to return them in a timely manner. M-10-13 also set out the consequence, “If a high-priority program does not meet its supplemental targets for two consecutive years, then it is required to submit a report to the Director of OMB.”

The Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Act of 2010 (IPERA, July 22, 2010) codified many of the requirements from M-10-13 in statute. IPERA additionally required IGs to annually audit agencies to assure compliance with all requirements and reduced the threshold definition of “significant” overpayments. OMB guidance (M-11-16, April 14, 2011) reduced the threshold further from 2.5% to 1.5% improper payments as a percent of all payments, regardless of dollar amount, beginning in fiscal year 2014.

Congress held 4, 15, and 11 hearings in fiscal years 2010, 2011, and 2012, with 80 witnesses from 13 different agencies called to testify. This oversight culminated in the Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Improvement Act of 2012, signed into law January 10, 2013, which codified many of the requirements from M-11-16. It additionally required agencies to check contract awardees against databases of death records, excluded parties from the Government Services Agency, credit risks, and excluded individuals from Health and Human Services payments, along with any other databases identified by OMB. The “Do Not Pay Initiative” required all agencies to check all current and future awards against the databases by June 1, 2013.

From fiscal 2013 to 2021, Congress held 37 hearings with 93 witnesses from 12 different agencies. The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (March 5, 2020) consolidated previous improper payment acts and allowed OMB to establish pilot programs to test potential accountability mechanisms for agencies. The bill established an interagency working group on payment integrity. Issuing guidance M-21-19 (March 5, 2021) directed programs with annual outlays above $10 million to conduct risk assessment at least once every three years.

Members of Congress and witnesses from the bureaucracy discuss the reporting, causes, and solutions for reducing improper payments in the congressional hearings on improper payments in our sample. In the hearings, bureaucrats report that they are focusing on improper payments, typically listing the resources and effort agencies devote to reporting improper payments and detailing the reasons or challenges standing in the way of decreases. Bureaucrats also regularly report the corrective actions that their agencies have implemented to reduce improper payments, accompanied by either success stories or reasons why the actions have been unsuccessful.

Congress uses the formal stature of the hearings to signal to agencies that reducing improper payments ought to be a bureaucratic priority. Members publicly push bureaucrats to identify and take specific corrective action. For example, in a September 22, 2016 hearing, the Chair of the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Mark Meadows, was frustrated with the Department of Health and Human Services for blaming stakeholders and other parties for their improper payments and wanted their Deputy Chief Financial Officer to identify specific actions to try and reduce improper payments:

Meadows: “So here’s what I would like…I need from you, specifically, what we’re going to do different between now and next year this time when we have this same report that comes out where we start to reverse the trend. I need a specific—not that ‘it’s important,’ not that ‘it’s this.’ I need ‘how are we going to address these particular issues?”’ (Committee on Oversight and Accountability 2016)

Both parties push agencies to take concrete steps; Subcommittee Ranking Member Gerald Connolly agreed with Meadows and declared oversight to be a collaborative way for Congress to work with agencies to effect material change.

Connolly: “The chairman asked that you come back to us with strategies that we can sort of sink our teeth into in the new year…So I think we approach this in the spirit of trying to partner with you, that get our arms around this collectively as a government, because a lot of good can come out of this. And bad things happen when this is left unaddressed. So I wish you’d get back to us with the fraud estimates so that we have—we can work with you in devising strategies and try to fight for getting the resources you need for those strategies” (Committee on Oversight and Accountability 2016).

Committee oversight staffers confirm that hearings signal congressional priorities to agencies. In a background interview, the chief oversight counsel to a congressional committee reported to us, “when we hold a hearing, when we yell at the [agency], it actually does matter, they need to know that there is some publicity, heat, transparency, if they’re doing things that we think are not appropriate.”Footnote 2 In another interview, the staff director for oversight on a different committee also reported that committees intend for hearings to help leaders in the agency prioritize, emphasizing the importance of the publicity surrounding public hearings: “Things aren’t prioritized without public attention… hearings help them prioritize. If we make our opinion known, especially in a hearing, it does seem to cause more shepherding of the issue by senior executives.”Footnote 3

One might wonder how agencies could tackle the thorny problem of improper payments. In the same hearing as above, the Department of Health and Human Services reported, “[W]e believe that the corrective actions that could have the biggest impact on preventing and reducing erroneous payments fall under three distinct areas: leveraging technology, strengthening partnerships, and exploring innovative solutions.” We summarize two HHS programs that improved their improper payment rates in Section F of the Supplementary Material to give interested readers a sense of what Corrective Action Plan procedures were used by programs who improved improper payment rates. It appears that vendor education and outreach to encourage appropriate documentation and to clarify processes and procedures were central to HHS remediation efforts.

The history of congressional and executive efforts to reduce improper payments along with our interviews and read of hearing transcripts indicate that improper payments are a bureaucratic outcome of relevance to Congress. This same set of evidence also explains why oversight could motivate bureaucratic change—because oversight signals to agencies how Congress would like them to allocate their limited time and resources.

The improper payments setting provides a unique research opportunity because oversight hearings invited witnesses from different agencies in different fiscal years. This allows us to estimate the effect of oversight hearings on improper payment rates at the agency and program level by comparing rates of programs called to testify to rates of programs without hearings across time.

Our empirical setting and measure of bureaucratic outcome advance previous work evaluating congressional oversight through circumvention of issues that have hindered systematic assessment of the efficacy of oversight. Previous work has focused on when oversight is conducted (e.g., Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990; Lowande and Potter Reference Lowande and Potter2021; MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016; McGrath Reference McGrath2013), outlined the need for a measure of oversight’s effectiveness (Levin and Bean Reference Levin and Bean2018), or used surveys of bureaucratic opinion (Clinton, Lewis, and Selin Reference Clinton, Lewis and Selin2014). The history of actions on improper payments shows that both Congress and the president, across both parties, agree in what they want from agencies: lower improper payments. This near-universal agreement in the directives to agencies on the issue of improper payments reduces the problems of multiple principals, interbranch competition, and heterogeneous preferences that the literature on legislative control of the bureaucracy highlights as challenges (e.g., Clinton, Lewis, and Selin Reference Clinton, Lewis and Selin2014; Gailmard Reference Gailmard2009; Volden Reference Volden2002; Wilson Reference Wilson1989). In the next section, we describe our data, research design, and strategy of identification.

DATA, RESEARCH DESIGN, AND IDENTIFICATION

To evaluate the effect of congressional oversight on improper payments in the bureaucracy, we compile and link new data from federal fiscal years 2000 to 2021 on (1) improper payments by agency programs and (2) congressional committee hearings on improper payments.

Improper Payments

We collect data on improper payments using a combination of government sources. First, the OMB-run website PaymentAccuracy.gov provides data on improper payments for federal fiscal years 2015 and forward. These data include the improper payment amounts and rates at the program level for all programs subject to statutory reporting requirements.

To extend these improper payments data earlier than 2015, we collected annual financial reports for each agency. This required scouring current and archived versions of each agency’s internet pages to locate a copy of the annual report. Each annual financial report includes fiscal year improper payments estimates for at-risk programs in that agency. The starting year of improper payments data differs by agency based upon availability of archived financial reports. The earliest fiscal year for which coverage started was 2000 (Social Security Administration) and the latest fiscal year for which coverage started was 2012 (12 agencies).

Table A1 in the Supplementary Material describes the year coverage by agency of our resulting improper payments dataset. Note that due to different years of reporting and at-risk determinations, different agencies and programs have different years of coverage.Footnote 4

It is important to note that our improper payments data only cover programs subject to statutory reporting requirements from the legislation and OMB guidance discussed in the previous section. As a result, our analysis estimates the effect of oversight for programs deemed at-risk for substantial improper payments as defined by Congress and the executive branch. While this might not be the experiment one would design to estimate the most general effect of oversight, we believe the censored sample should be of limited concern. The potential effect of oversight on the set of programs deemed low-risk for improper payments seems likely to be lower than the potential effect on programs deemed at-risk. Low-risk programs have lower (or zero) improper payment rates, and so there is a ceiling on the efficacy of oversight on improving performance for the programs excluded from our sample. Averaging this smaller effect of low-risk programs excluded from our sample with a larger effect for at-risk programs included in our sample would yield an average effect of oversight on all programs smaller than what we estimate here. Because we conclude that the effectiveness of oversight is limited, the full-sample effect would likely demonstrate an even smaller effect of oversight, strengthening rather than weakening our conclusion.

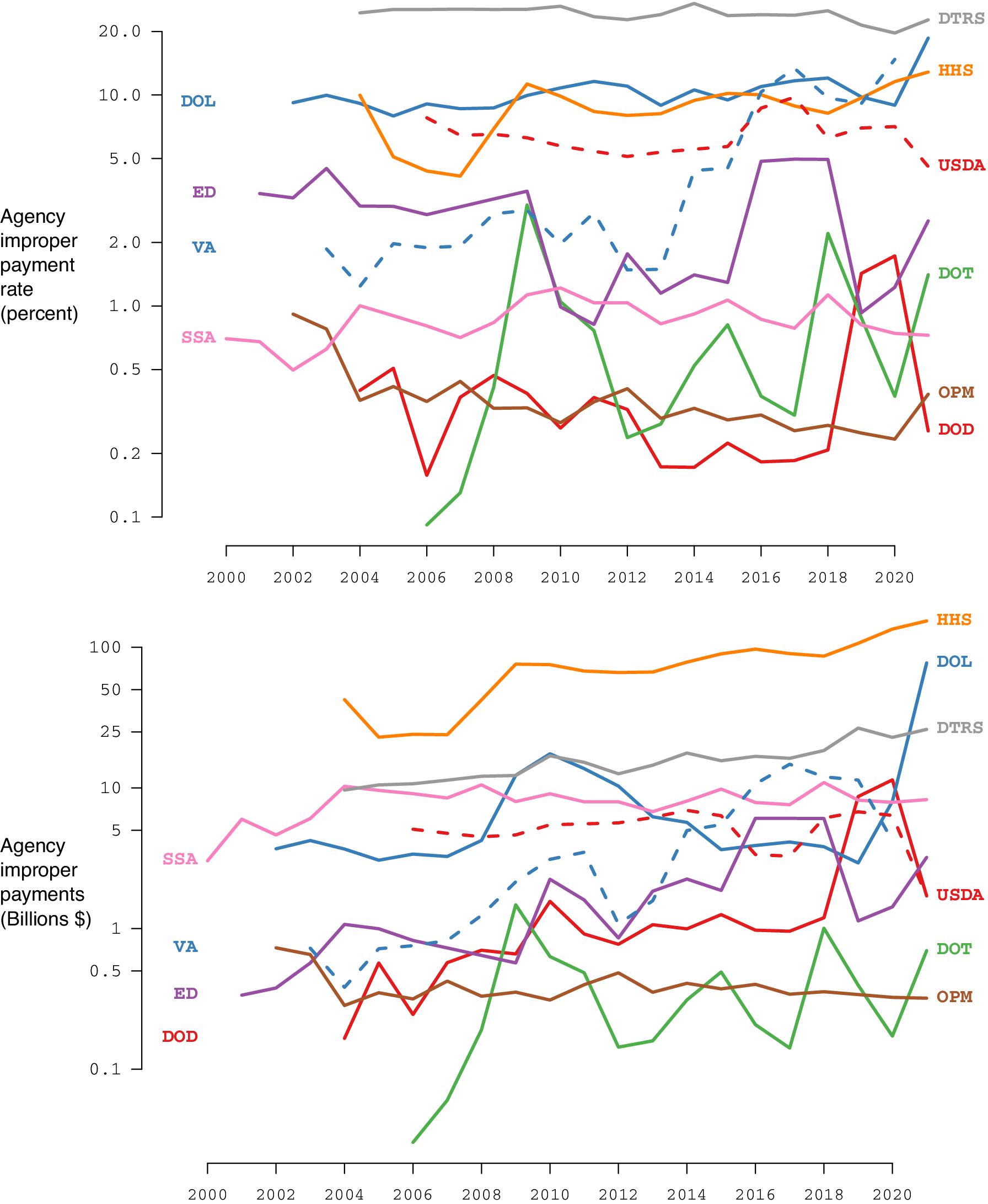

In Figure 1, we present agency-level trends in improper payments by year for the ten largest-outlay agencies. The top frame presents improper payment rate as a percentage of total payments, the bottom the dollar amount of improper payments. The top frame shows that the Department of the Treasury had the highest rate of improper payments during this time period with more than one out of every five dollars in outlays deemed improper. This is because the IRS has a hard time confirming the accuracy of payments for the Earned Income Tax Credit program. Other agencies with large rates of improper payments are Labor, Agriculture, and Health and Human Services (HHS), whose improper payment rates are on the order of 5– 10%.

Figure 1. Improper Payment Rates and Amounts by Fiscal Year and Agency, 10 Largest Agencies by Total Outlays

Note: Y-axes on log scale.

While some agencies have relatively constant rates of improper payments, others see year to year variability and secular trends. Our research design will ask whether congressional hearings predict these changes. As an overall picture, however, one would probably not conclude that Congress’s two decades of effort to rein in improper payments have been successful. Typical improper payment rates in 2020 are no lower than typical rates in 2003. Our regression results confirm this observation, suggesting limits to Congress’s ability to control the bureaucracy.

The bottom frame presents total improper payments by fiscal year and highlights the magnitude of the problem. In recent fiscal years, HHS has improper payments that exceed $100 billion, Labor above $50 billion, and Treasury above $10 billion. Somewhere around one half of improper payments are eventually recovered, so these numbers are larger than the total losses to the taxpayer. But even cutting these numbers in half indicates a large sum that one would imagine many members of Congress would like to use for other purposes.Footnote 5

Oversight Hearings

To identify congressional committee oversight hearings on improper payments, we use data from Ban, Park, and You (Reference Ban, Park and You2023), which cover the names and affiliations of the witnesses testifying and the transcripts of congressional hearings. We identify hearings on improper payments as hearings which mention a set of phrases related to improper payments in at least one of four fields that represent the focus of a hearing: title, summary, subjects, or testimony subjects of the hearing, as specified by ProQuest Congressional.Footnote 6 By filtering for mentions of improper payments in these four descriptive fields of the hearings, we identify hearings that committees held with the intent of reviewing and discussing improper payments.Footnote 7

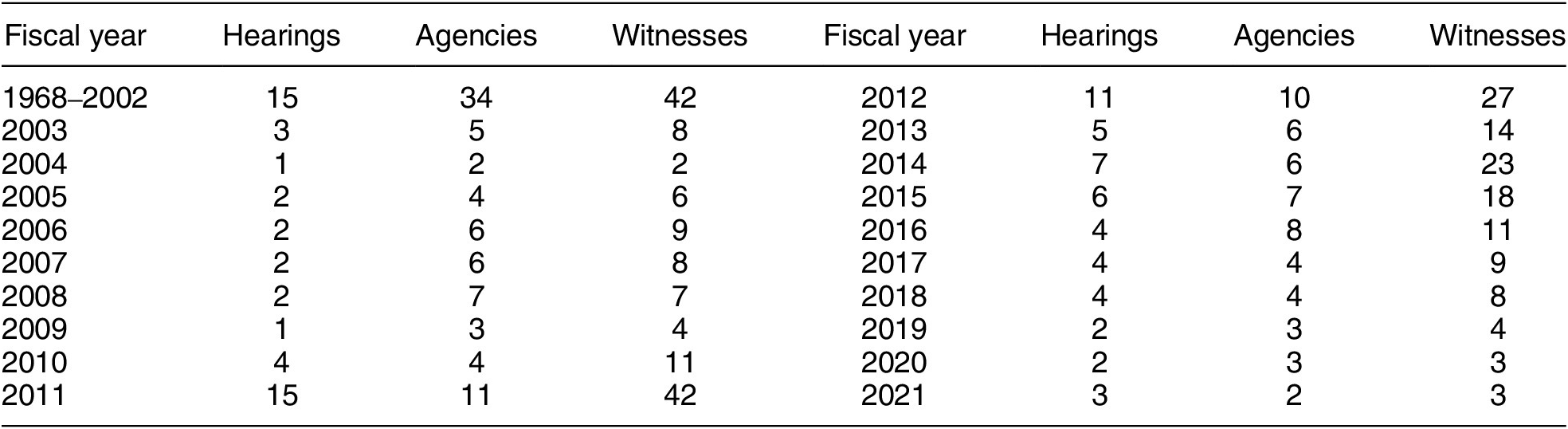

Improper payment hearings invite testimony from employees of executive agencies and programs. We use the affiliations of the bureaucratic witnesses to identify the agencies overseen in the hearing by matching witnesses to the 15 executive departments and 55 independent agencies in the federal government as defined by the Office of Personnel Management (we use the word “agency” to refer to the executive department or independent agency level).Footnote 8 Generally, these witnesses are Assistant Secretary or Director level within an agency or the Chief Financial Officer, Controller, Inspector General, or their deputies, of an agency or office within the agency. While hearings may mention certain programs or discuss program-level details, the witnesses invited have positions and job responsibilities at the agency-level and so we view improper payments hearings as agency-level stimulus. In Table 1, we summarize improper payment hearings held by Congress since 1968, tabulating the number of hearings, witnesses, and agencies called to oversight by fiscal year (summing across House and Senate). In Table A2 in the Supplementary Material, we tabulate the count of hearings by congressional committee, showing that improper payment hearings are mostly, but not exclusively, held by House and Senate oversight committees and Ways and Means.

Table 1. Improper Payments Hearings by Federal Fiscal Year

Note: Witness counts exclude non-bureaucratic witnesses.

Research Design and Identification

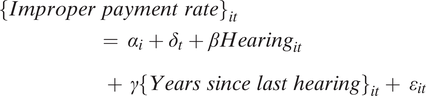

To estimate the effect of improper payment hearings on improper payment rates, we use a two-way fixed effects identification strategy. Because we are uncertain about how long it might take for agencies to enact reforms to improve their improper payment problems, we estimate a linear trend in improper payments in the years following a hearing. Our specification is

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\left\{Improper\hskip0.3em payment\hskip0.3em rate\right\}}_{it}\\ {}\hskip5em ={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\alpha}_i+{\delta}_t+\beta Hearin{g}_{it}\\ {}\hskip-1em +\hskip0.35em \gamma {\left\{Years\hskip0.3em since\hskip0.3em last\hskip0.3em hearing\right\}}_{it}+\hskip2px {\varepsilon}_{it}\end{array}}\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\left\{Improper\hskip0.3em payment\hskip0.3em rate\right\}}_{it}\\ {}\hskip5em ={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\alpha}_i+{\delta}_t+\beta Hearin{g}_{it}\\ {}\hskip-1em +\hskip0.35em \gamma {\left\{Years\hskip0.3em since\hskip0.3em last\hskip0.3em hearing\right\}}_{it}+\hskip2px {\varepsilon}_{it}\end{array}}\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ {\{Improper\hskip0.3em payment\hskip0.3em rate\}}_{it} $

is the sample-estimated improper payment rate of agency i in fiscal year t,

$ {\{Improper\hskip0.3em payment\hskip0.3em rate\}}_{it} $

is the sample-estimated improper payment rate of agency i in fiscal year t,

![]() $ Hearin{g}_{it} $

takes the value 1 if a witness from agency i testified in at least one oversight hearing on improper payments in year t,

$ Hearin{g}_{it} $

takes the value 1 if a witness from agency i testified in at least one oversight hearing on improper payments in year t,

![]() $ {\{Years\hskip0.3em since\hskip0.3em last\hskip0.3em hearing\}}_{it} $

counts the number of fiscal years since a witness from that agency was most recently called to testify (year of hearing equals zero), and

$ {\{Years\hskip0.3em since\hskip0.3em last\hskip0.3em hearing\}}_{it} $

counts the number of fiscal years since a witness from that agency was most recently called to testify (year of hearing equals zero), and

![]() $ \alpha $

and

$ \alpha $

and

![]() $ \delta $

are agency and fiscal year fixed effects. These fixed effects capture time-invariant features of agencies (policy domain, relative budget size, etc.) and factors that affect all agencies in each fiscal year (new statutes or executive orders, budget environment, economic conditions, focus of presidential administration, GAO involvement in hearings, etc.).

$ \delta $

are agency and fiscal year fixed effects. These fixed effects capture time-invariant features of agencies (policy domain, relative budget size, etc.) and factors that affect all agencies in each fiscal year (new statutes or executive orders, budget environment, economic conditions, focus of presidential administration, GAO involvement in hearings, etc.).

The coefficient

![]() $ \beta $

measures the effect of oversight hearing on improper payments in the year of the hearing.Footnote

9 Because agencies estimate improper payments by sampling from payment databases in fiscal years subsequent to that of the payments, the hearing might influence the measurement of IP rate in the fiscal year of the hearing. To estimate improper payments in fiscal year 2010, in fiscal 2011 an agency samples from their database of fiscal 2010 payments and then attempts to verify the propriety of each sampled 2010 payment. Thus a hearing in fiscal 2010 could influence either the payment choices in the remainder of fiscal 2010 or the evaluation efforts in fiscal 2010 or 2011. Because of the multiple causal pathways influencing β, this coefficient might be positive if the agency exerts additional efforts to identify improper payments following the hearing, negative if the agency exerts additional efforts to prevent improper payments following the hearing, or some mixture of the two.

$ \beta $

measures the effect of oversight hearing on improper payments in the year of the hearing.Footnote

9 Because agencies estimate improper payments by sampling from payment databases in fiscal years subsequent to that of the payments, the hearing might influence the measurement of IP rate in the fiscal year of the hearing. To estimate improper payments in fiscal year 2010, in fiscal 2011 an agency samples from their database of fiscal 2010 payments and then attempts to verify the propriety of each sampled 2010 payment. Thus a hearing in fiscal 2010 could influence either the payment choices in the remainder of fiscal 2010 or the evaluation efforts in fiscal 2010 or 2011. Because of the multiple causal pathways influencing β, this coefficient might be positive if the agency exerts additional efforts to identify improper payments following the hearing, negative if the agency exerts additional efforts to prevent improper payments following the hearing, or some mixture of the two.

Due to the ambiguous predictions about

![]() $ \beta $

as well as uncertain temporal dynamics of remediation, we also estimate a time-forward linear effect of the hearing with the coefficient γ. This specification is somewhat unusual and so demands comment. Reforms to improve improper payments tend to require long-term investments in training, technology, and procedures along with learning about and revision to best practices. Thus we expect theoretically that the attention prompted by oversight hearings will not immediately improve improper payment rates but would, instead, improve rates as time passes and the agency implements reforms. Agency testimony supports this theoretical expectation, suggesting that reforms can take multiple years before fully effective.Footnote

10

$ \beta $

as well as uncertain temporal dynamics of remediation, we also estimate a time-forward linear effect of the hearing with the coefficient γ. This specification is somewhat unusual and so demands comment. Reforms to improve improper payments tend to require long-term investments in training, technology, and procedures along with learning about and revision to best practices. Thus we expect theoretically that the attention prompted by oversight hearings will not immediately improve improper payment rates but would, instead, improve rates as time passes and the agency implements reforms. Agency testimony supports this theoretical expectation, suggesting that reforms can take multiple years before fully effective.Footnote

10

The linear trend in time serves as an approximation to the slowly unfolding process of agency reform. Thus

![]() $ \gamma $

serves as our key estimate of the efficacy of congressional oversight. If oversight leads to improvement in the agency’s payment procedures, improper payment rate should improve (negative coefficient

$ \gamma $

serves as our key estimate of the efficacy of congressional oversight. If oversight leads to improvement in the agency’s payment procedures, improper payment rate should improve (negative coefficient

![]() $ \gamma $

) in the years following the hearing.

$ \gamma $

) in the years following the hearing.

Some readers might object to the statistical assumptions surrounding the linear trend specification. We add two alternative specifications—an intercept-shift model and a semi-parametric dynamic model—to allay concerns about specification error, which we discuss below. Results from both alternatives are consistent with the linear specification.

Improper payment rates are also estimated at the level of programs (multiple programs per agency) and so in a second specification, we complement the agency-level analysis with a program-level regression with the same specification but with i indexing programs instead of agencies. Program fixed effects capture all time-invariant features of programs including program policy portfolio, relative program budget size, and relative program use of contractors or type of payments. Because, however, nearly all witnesses represent agencies (e.g., inspectors general, payment administrators for the full agency) rather than individual programs, our hearing variables remain measured with agency-level witnesses. We therefore cluster standard errors on the agency-year for all program-level analysis.

Program fixed effects also address the concern that Congress has differential concern about improper payments for different agencies. Congress might be more lenient with improper payments for certain programs that provide politically salient benefits such as FEMA assistance, food stamps, or federal student aid. Program fixed effects allow Congress to have different thresholds of “acceptable” improper payment rates across programs while also modeling oversight hearings as a mechanism to return excess rates to different acceptable levels. Suppose, for example, that Congress is willing to accept an improper payment rate of 10% for FEMA but 2% for the Small Business Administration because they are willing to take more improper payments in exchange for FEMA grants being made promptly with less paperwork than in exchange for SBA loans being made promptly with less paperwork. The program fixed effects hold constant these average differences between the two programs. The regression coefficient on hearings, therefore, measures the average change in improper payment rate relative to the program-specific averages in response to a hearing with a witness from that program’s agency.

Unbiased estimates of

![]() $ \beta $

and

$ \beta $

and

![]() $ \gamma $

require the usual two-way fixed effects assumption of parallel trends, that the path of improper payment rate for agencies called to testify would have followed the path of agencies not called to testify were the witness not invited to the hearing. In the Supplementary Material, we offer two evaluations of the parallel trends assumption. In Figure A1 in the Supplementary Material, we plot time-series of improper payment rates by program for agencies with witnesses called to testify on improper payments. The figure demonstrates no pattern of improper payment rates in the years prior to a hearing. In Table A3 in the Supplementary Material, we regress an indicator for oversight hearing in that fiscal year on lags of IP rate and IP amount. We find that lagged changes in improper payments do not predict incidence of oversight hearings, suggesting that our result is not driven by selection to treatment issues.

$ \gamma $

require the usual two-way fixed effects assumption of parallel trends, that the path of improper payment rate for agencies called to testify would have followed the path of agencies not called to testify were the witness not invited to the hearing. In the Supplementary Material, we offer two evaluations of the parallel trends assumption. In Figure A1 in the Supplementary Material, we plot time-series of improper payment rates by program for agencies with witnesses called to testify on improper payments. The figure demonstrates no pattern of improper payment rates in the years prior to a hearing. In Table A3 in the Supplementary Material, we regress an indicator for oversight hearing in that fiscal year on lags of IP rate and IP amount. We find that lagged changes in improper payments do not predict incidence of oversight hearings, suggesting that our result is not driven by selection to treatment issues.

LEGISLATIVE CONTROL AND OVERSIGHT RESULTS

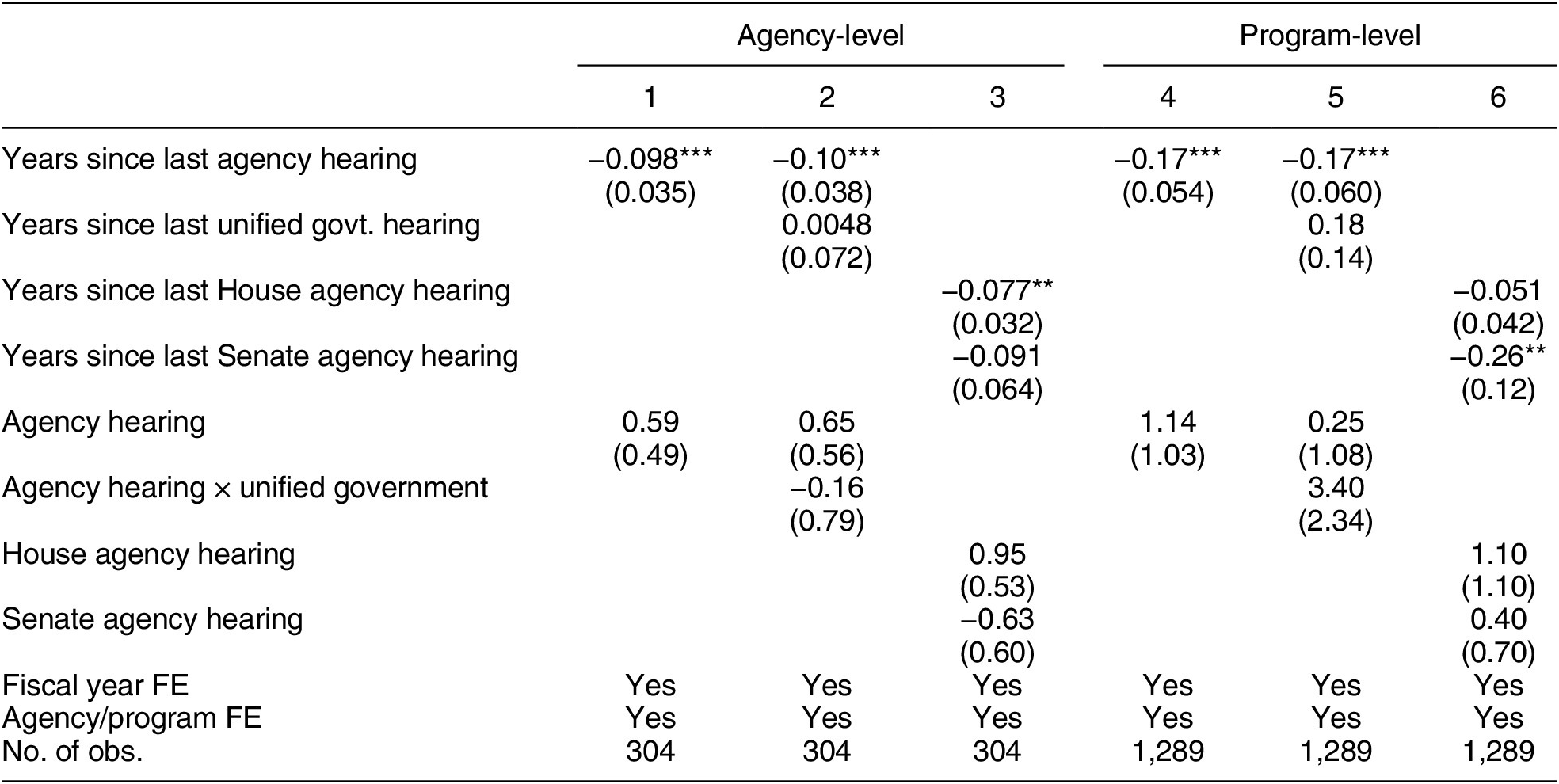

In Table 2, we present estimates from Equation 1 at the agency (columns 1–3) and program (4–6) level. Column 1 presents results combining House and Senate hearings into single variables. The coefficients indicate that in each year following a hearing with a witness from that agency, improper payment rate falls by about 0.1 percentage points.Footnote 11

Table 2. Dynamic Effect of Hearings on Improper Payment Rate

Note: Dependent variable is improper payment rate as a percent of all payments. Standard errors in parentheses; clustered on agency-year for program-level analysis. **

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, ***

$ p<0.05 $

, ***

![]() $ p<0.01. $

$ p<0.01. $

In column 2, we estimate variability in effects by whether the hearing was held under unified government. Kriner and Schickler (Reference Kriner and Schickler2016) find oversight more frequent during periods of divided government. While the standard error is large, the point estimate suggests that hearings held under unified government lead to twice the decline in IP rate than hearings held under divided government. Column 3 suggests that both House and Senate hearings lead to subsequent declines in improper payments. The two coefficients are −0.08 (House) and −0.09 (Senate) with standard errors that do not allow us to distinguish between them.

Columns 4–6 present the same specifications for a program-level analysis. We find that improper payment rates decline, on average, by about 0.17 percentage points each year following a hearing (column 4). We do not find evidence that this decline varies by whether the hearing happened under unified government (column 5). Point estimates suggest that Senate hearings are more consequential than House hearings at the program level (column 6).

The results of Table 2 suggest that oversight hearings lead to a subsequent decline in improper payment rates for agencies with witnesses called to testify. Oversight changes bureaucratic performance. However, the magnitude of the effect is somewhat limited. For each year beyond the hearing, improper payment rate improves by 0.1% (agency) to 0.2% (program), on average.

We interpret the effect sizes as small in comparison to overall levels of improper payment rates. The mean improper payment rate in 2021 was 5.9% and the dollar-weighted mean almost 8%. While a 0.1 or 0.2% improvement in the improper payment rate corresponds to millions of dollars of savings, such improvements do not much dent the hundreds of billions of dollars of improper payments. For example, the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Highway Planning and Construction Program in the Department of Transportation had an improper payment rate of 1.41% in 2021, or $697 million on $49 billion of outlays. Our finding of oversight’s average program-level effect of 0.2%, then, represents a predicted reduction of $99 million, leaving over $598 million remaining in improper payments.Footnote 12

Robustness to Specification, Identification, and Measurement Choices

In this section, we summarize efforts we have made to probe the robustness of our results to the design choices that underly our estimates in Table 2.

A first design choice is our specification of the effect of an oversight hearing as linear in the years following the hearing. To probe the empirical robustness of our result to the linear specification, we estimate two alternative regression specifications that allow for different dynamic effects of oversight hearings. In Table A4 in the Supplementary Material, we first estimate an intercept-shift model where instead of the effect of a hearing evolving linearly in the years after the hearing, we instead estimate an intercept-shift in average improper payment rate in all years after the hearing. Both agency- and program-level results suggest oversight leads to an average 1.5 percentage points lower improper payment rate in the fiscal years following a hearing.

A second semi-parametric specification (columns 2 and 4) allows the dynamic effect of a hearing to unfold in an arbitrary pattern in the years following a hearing. Agency estimates of improper payment rates are higher in the year of and the year following a hearing relative to the year prior to the hearing, but then decline in years 2, 3, and 4 after the hearing relative to year of hearing. In total, Table A4 in the Supplementary Material shows our conclusions about oversight dynamics are robust to the assumption of effects linear in time.

A second design choice is use of the two-way fixed effects (TWFE) estimator. Recent econometrics scholarship has shown that the TWFE estimator in the presence of staggered treatments leads to comparisons between treated and already-treated units, which can bias estimates. In Section C of the Supplementary Material, we present results from a local projection difference-in-differences estimator with the binary version of treatment to remove comparison to already-treated units. The results from this alternative estimator yield large standard errors on the effect of an Agency Hearing and do not indicate a substantial effect of oversight on improper payment rates.

The effect of oversight we estimate in Table 2 averages across all agencies (all programs) in the dataset. Figure 1 shows, however, substantial variation in levels of improper payment rates across agencies. For example, while Treasury averages around 20%, OPM averages less than 1%. It could be that achieving improvement in improper payments is simpler for programs with large rates than for programs with rates that are already small. In Table A7 in the Supplementary Material, we partition our sample into agencies (programs) with average improper payment rates below and above the median agency (program) rate. The point estimates do indicate that oversight hearings lead to larger declines in improper payment rates for agencies (programs) with higher average rates, though larger standard errors limit confidence in that conclusion.Footnote 13

Our main specification focuses on the dynamic effect of hearings with witnesses from the agency from a single fiscal year. Agency effort on improper payments, however, might be affected by other vectors of oversight. For example, effort might increase as a function of the cumulative number of improper payment hearings targeting the agency over multiple years, hearings on improper payments targeting peer agencies, hearings held in years with statutory action on improper payments, or the proportion of hearings on improper payments compared to other issues. We discuss and address the possible effects of these vectors of oversight in Section D of the Supplementary Material.

Overall, the results for the direct dynamic effect of oversight remain robust when accounting for cumulative number of hearings for an agency (columns 1 and 5 in Table A8 in the Supplementary Material), oversight spillover among peer agencies (columns 2 and 6), hearings in years with statutory activity (columns 3 and 7), proportion of hearings on improper payments (columns 4 and 8), or congressional investment in agency resources (Table A9 in the Supplementary Material). We find large standard errors and small negative or near zero effects on a peer agency’s improper payments in the years following committee oversight spillover. Oversight hearings have larger effects in years with statutory activity, but standard errors are again quite large. We find null results for the effect of proportion of oversight on improper payments.

Moderators of Legislative Oversight

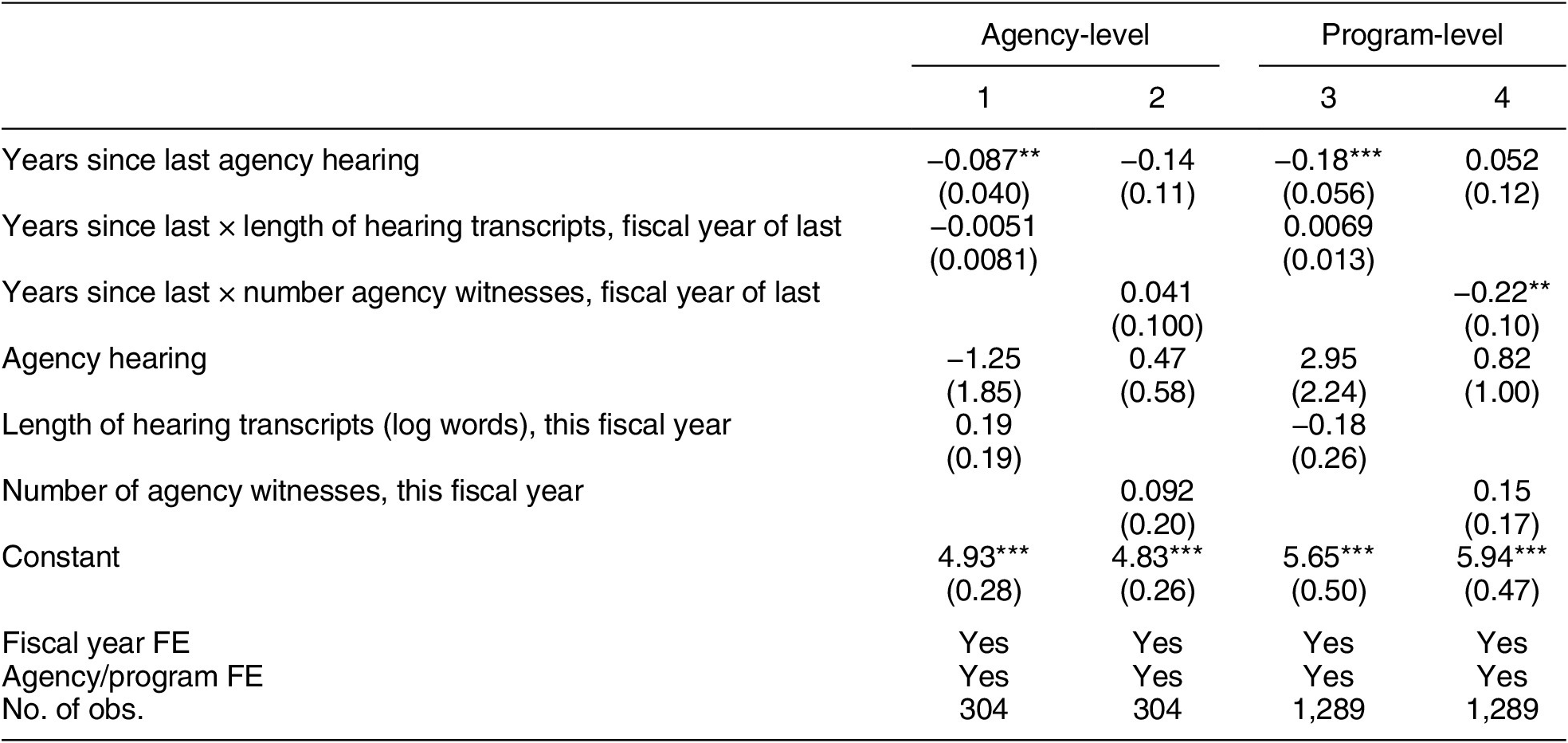

We next consider whether characteristics of hearings moderate the effect on improper payments. We collected four hearing characteristics that each try to approximate higher quality of hearing or higher stimulus to the agency: (1) the number of agency witnesses called to testify across all hearings on improper payments in that fiscal year, (2) the length of hearings with witnesses from that agency in that fiscal year measured by log word count, (3) the number of total witnesses (i.e., including non-agency witnesses such as those from GAO or OMB in the count) called to testify in improper payment hearings referencing that agency in that fiscal year, and (4) the number of agency witnesses who are political appointees called to testify in that fiscal year. We also collected hearing characteristics that capture higher exposure of the hearing for the agency: (5) hearings at the full committee versus subcommittee level and (6) hearings held during a presidential election year. While none of these variables perfectly measure the “strength of oversight” we would like to capture, they each circle that target. The first two moderators are perhaps the closest proxies, as the number of agency witnesses called to testify and the length of the hearing are directly increasing with amount of attention and detail the committee gives to the issue. Table 3 presents the results on the dynamic effect of the first two moderators on improper payment rates; Table A10 in the Supplementary Material presents results for the remaining.

Table 3. Dynamic Effect of Moderators on Improper Payment Rate

Note: Dependent variable is improper payment rate as a percent of all payments. Standard errors in parentheses; clustered on agency-year for program-level analysis. **

![]() $ \mathrm{p}<0.05 $

, ***

$ \mathrm{p}<0.05 $

, ***

![]() $ \mathrm{p}<0.01. $

$ \mathrm{p}<0.01. $

None of the moderators in Table 3 offer clear improvement in fit. Standard errors are generally large. Point estimates offer some suggestive evidence at the agency level that the length of the hearing leads to an initial increase in estimated improper payment rate in the first year following the hearing but then leads to a decline in years after that. This is similar to our main finding above but with larger sampling uncertainty. Corresponding point estimates at the program level, however, run counter to this pattern. Point estimates for the number of agency witnesses follow the pattern of the main finding at the program level, but is negligible with large standard errors at the agency level.Footnote 14 Large standard errors are also found for the number of total witnesses, whether the hearing was held at the subcommittee or full committee level, and whether the hearing was held during a presidential general election year (Table A10 in the Supplementary Material). We find some evidence that a hearing called with more agency witnesses who are political appointees leads to increases in improper payment rates at the agency level.

OTHER METHODS OF LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE CONTROL

Our main analysis centers on congressional committee hearings as the tool of oversight, following existing literature that focuses on hearings (e.g., Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990; Fowler Reference Fowler2015; Kriner and Schickler Reference Kriner and Schickler2016; MacDonald and McGrath Reference MacDonald and McGrath2016; McGrath Reference McGrath2013). Might congressional oversight of improper payments, however, operate through other channels?

Congress, its committees, or individual members can use non-hearing techniques to conduct oversight (Selin and Moore Reference Selin and Moore2023). The president also uses various actions to mitigate the control problem within the executive branch. In this section, we consider the use of these other methods of legislative and executive control to reduce improper payments.

We begin with the congressional practice of correspondence as a method of control. Studies such as Lowande (Reference Lowande2018) and Ritchie (Reference Ritchie2018) focus on inquiries (contacts) made by individual legislators to agencies. This form of communication is informal and nonstatutory but, as with hearings, can take the form of oversight as communication between legislature and agency about legislative priorities.

Using data from Lowande and Ritchie (Reference Lowande and Ritchie2020), we examine all contacts between legislators and agencies from the time period available that overlaps with our main analysis, fiscal years 2005–14. We find that out of the 11 agencies for which contacts data are available, the description for 80 out of 34,419 total contacts refers to a topic related to agency payment issues.Footnote 15 This small number of contacts, less than our total count of hearings, implies that while contacts between individual legislators and agencies could be a channel of oversight for some matters, correspondence is not a medium for communication about improper payments.Footnote 16

Comparison to Appropriations Committee Reports, Statutes, and Executive Actions

The principals of the bureaucracy—Congress and the president—have methods outside of what is typically considered oversight to try and control agency behavior. Congress can legislate and issue appropriation committee reports. The president can issue executive orders. OMB can issue memoranda and bureaucratic guidance. We next compare the effectiveness of oversight to the effectiveness of congressional and executive tools that could also influence improper payments.Footnote 17

Scholars have characterized committee reports issued during the appropriations process as a channel through which the committees can instruct agencies on priorities, reporting requirements, or requirements to conduct certain activities or investigations (Bolton and Thrower Reference Bolton and Thrower2019; Kiewiet and McCubbins Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991). Bolton (Reference Bolton2022) and Schick (Reference Schick2008) argue that the appropriations committees can indirectly sustain agency cooperation through language in their annual reports.

We examine whether committee reports from the House Appropriations Committee addressing improper payments reduce subsequent improper payment rates. We collect the text of all committee reports issued by the House Appropriations Committee in fiscal years 2000–21 from Congress.gov. We classify committee reports as addressing improper payments if the report text includes one or more of the phrases relating to improper payments. This process yields 75 appropriations committee reports addressing improper payments.Footnote 18

Appropriation committee reports addressing improper payments can cover agencies in two ways. The report can cover an agency and directly refer to the agency’s own improper payments as needing attention. Or, the report can cover an agency but not directly refer to an agency’s improper payments, instead mentioning improper payments in general or mentioning a different agency’s improper payments (see Section D of the Supplementary Material for an example of each case). We manually code both of these instances for each report. While some reports address improper payments of specific programs within agencies, the majority of the reports only mention improper payments at the agency level.Footnote 19

Table A11 in the Supplementary Material presents the results on the effect of appropriations committee reports addressing improper payments on improper payment rates. Columns 1, 2, 7, and 8 show the estimated effect of an agency or program’s agency having its improper payments directly mentioned in a report. Point estimates are negative and small for both agency-level and program-level improper payment rates.Footnote 20 There is wide sampling variability in all cases, suggesting a lack of evidence for a definitive effect of appropriations reports on improper payments.

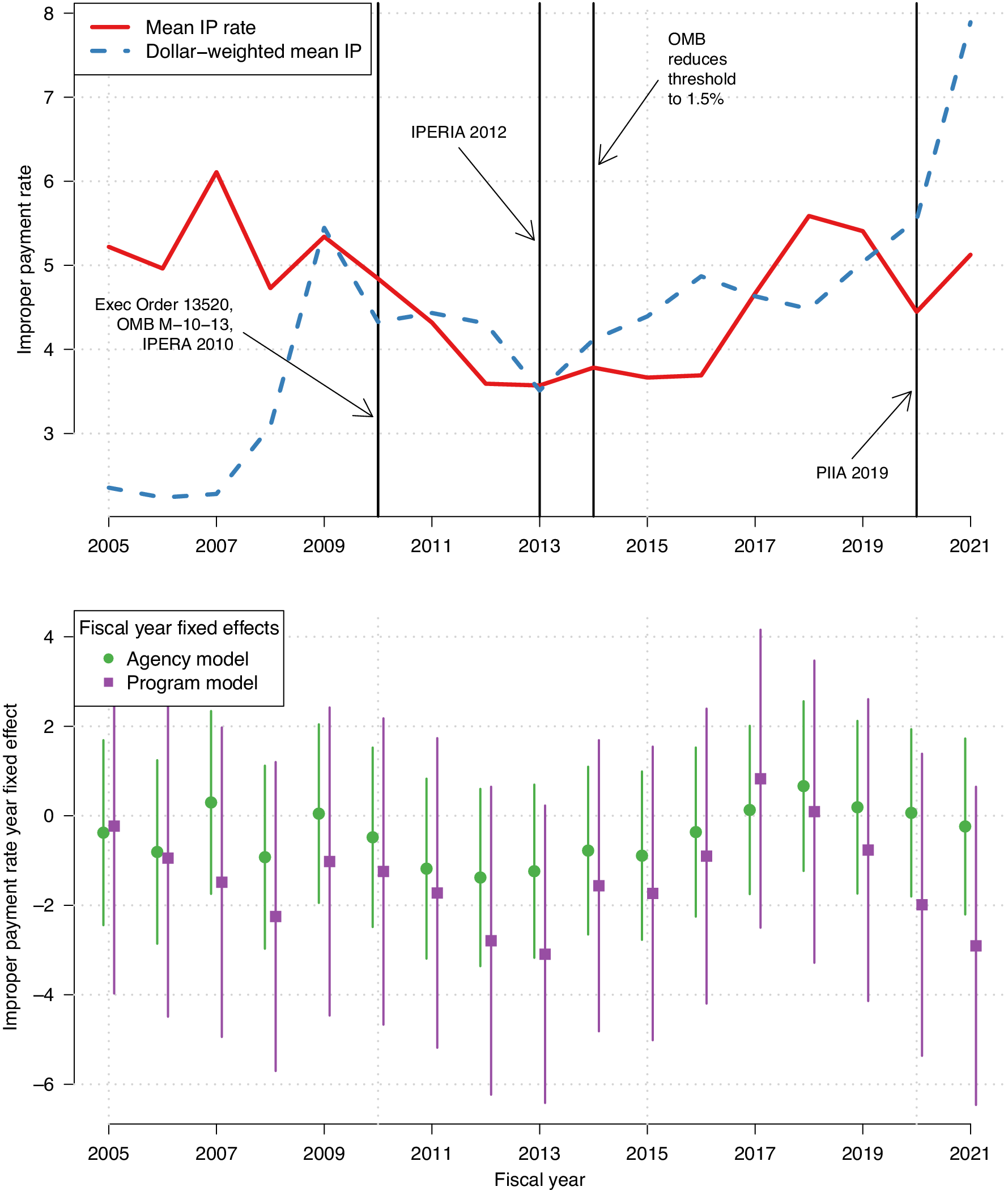

In Figure 2, we evaluate evidence on the efficacy of executive actions (the Obama executive order and significant OMB memoranda) and enacted statutes. The top frame plots the government-wide improper payment rate for fiscal years 2005–21. The solid line is the mean rate across agencies, the dashed line a mean weighted by outlay amounts. We plot vertical lines at four fiscal years with salient executive or statutory actions.

Figure 2. Improper Payment Rate Trends and Model Fixed Effect Estimates by Fiscal Year

Note: Lines in lower frame extend to 95% confidence intervals. Vertical lines match to the following events: Executive Order 13520, OMB memorandum M-10-13, and IPERA 2010 statute (fiscal 2010); IPERIA 2012 statute (fiscal 2013); threshold defining significant overpayments reduced to 1.5% (fiscal 2014); PIIA 2019 statute (fiscal 2020).

The fiscal year trends suggest some evidence of influence following the fiscal 2010 actions. Notably, the executive order and OMB guidance occur early enough in the fiscal year (November 2009 and March 2010) to influence payment practices for much of fiscal 2010. Both dollar-weighted and raw means decline from fiscal 2009 to fiscal 2010 and on to fiscal 2013 where they bottom out before beginning to rise after fiscal 2016. That said, we see no evidence of declines following the 2013, 2014, or 2020 executive actions and statutes, and the decline following 2009 is from an improper payment rate of around 5% to a rate of around 3.75% in 2013.

The aggregate means do not account for changes in composition of the programs reporting improper payments, which is a function of each program’s risk profile and mandatory evaluation schedule. The bottom frame attempts to fix the estimates by plotting the fiscal year fixed effects (

![]() $ {\delta}_t $

in Equation 1) from the models in Table 1, which include agency or program fixed effects (

$ {\delta}_t $

in Equation 1) from the models in Table 1, which include agency or program fixed effects (

![]() $ {\alpha}_i $

in Equation 1) to account for compositional changes. Above each fiscal year on the x-axis, we plot the fixed effect estimate from the agency-level model (solid circle) and from the program-level model (solid square) along with 95% confidence intervals.

$ {\alpha}_i $

in Equation 1) to account for compositional changes. Above each fiscal year on the x-axis, we plot the fixed effect estimate from the agency-level model (solid circle) and from the program-level model (solid square) along with 95% confidence intervals.

The fixed effect point estimates from both models replicate the pattern from the top frame, with the pre-2010 fixed effects greater than the 2010–14 fixed effects followed by an increase toward 2020. The point estimates suggest a decline in improper payment rates following fiscal 2018 at the program level. The size of the confidence intervals, however, does not allow for strong inferences about this pattern. Data from future years will allow evaluation of this decline.

Overall, while there are some years in which non-oversight congressional and executive actions may have reduced improper payments, the effectiveness of these actions has been muted and inconsistent. The magnitude of the decline in improper payments is, at most, 1.25 percentage points over a specific 4-year time period (fiscal years 2009–13), which is not reproduced in years following. Statutes, executive orders, and OMB guidance appear to offer, at best, the same limited efficacy of oversight hearings.

CONCLUSION

Congress holds the power and responsibility to conduct oversight of the executive branch to produce effective public policy. This oversight role has spawned many theories of congressional influence on the bureaucracy. On the one end, theories suggest Congress controls the bureaucracy and can successfully address problems with “fire alarm” oversight (Calvert, Moran, and Weingast Reference Calvert, Moran and Weingast1987; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Moran and Weingast Reference Moran and Weingast1982; Weingast Reference Weingast1984; Weingast and Moran Reference Weingast and Moran1983). On the other end, critics of dominance theories point out that congressional control of the bureaucracy is suspect for many reasons. Moe (Reference Moe1987) reminds the literature that bureaucrats have their own motivations and incentives that do not make them always subservient to Congress, and questions the efficacy of the tools practically available to Congress to influence the bureaucracy.