No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

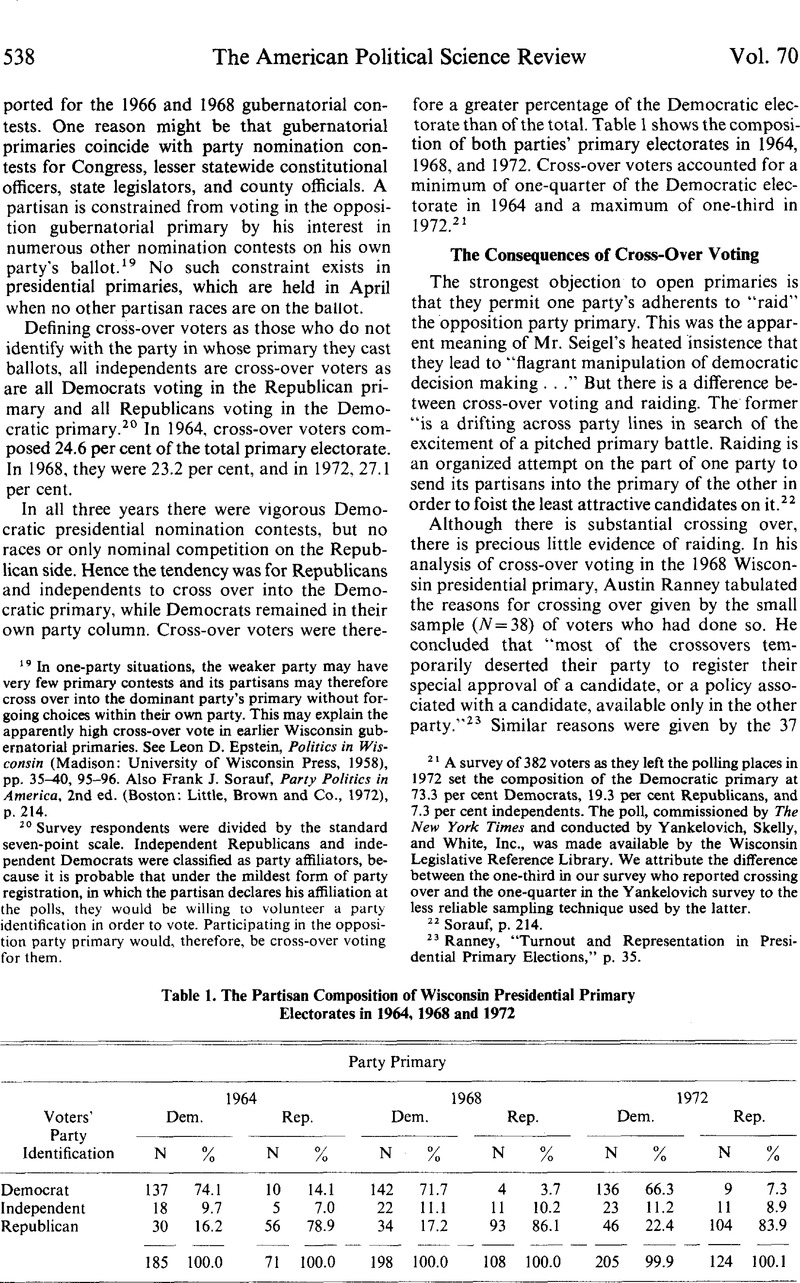

The Consequences of Cross-Over Voting

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Communications

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Political Science Association 1976

References

23 Ranney, , “Turnout and Representation in Presidential Primary Elections,” p. 35Google Scholar.

24 Ogden, , “Washington's Popular Primary,” p. 147Google Scholar.

25 Taking the unreliably small number of independents and Republicans separately in 1964 and 1968 shows that both groups voted differently from the Democrats. In 1964, independents gave a smaller majority to Reynolds than did Democrats, and Republicans supported Wallace. In 1968, both groups supported McCarthy more strongly than did Democrats, but again Republicans tended to be more dissimilar from the Democrats than were the independents.

26 Taking the unreliably small number of indepedents and Republicans separately in 1972 shows that the similarity between the cross-over vote for Humphrey and Muskie and the Democratic vote for them was caused by aggregating their higher support among independents and lower support among Republicans.

27 Democratic National Committee, Delegate Selection Rules for the 1976 Democratic National Convention (Washington, 1975), Rule 11, p. 6Google Scholar.

28 Pomper, Gerald, Nominating the President (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1966), p. 109Google Scholar. Also Polsby, Nelson W. and Wildavsky, Aaron B., Presidential Elections, 3rd ed. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971), pp. 131–133Google Scholar. Morris Udall put the point pungently when responding to a reporter's question whether he would enter the Wisconsin primary if the state's delegates would not be seated because the primary did not conform to Democratic party rules. “The whole early primary game is momentum and psychology … Even if it's not binding, even if it's a beauty contest, the Wisconsin primary is still important.” Wisconsin State Journal, September 21, 1975, section 1, page 4Google Scholar.

29 Crossing over may especially exaggerate the strength of incumbents or other well-known figures. Ogden, and Bone, , Washington Politics, p. 39Google Scholar. This may, of course, give these primary candidates a substantial psychological advantage as they enter the general election.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.