Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

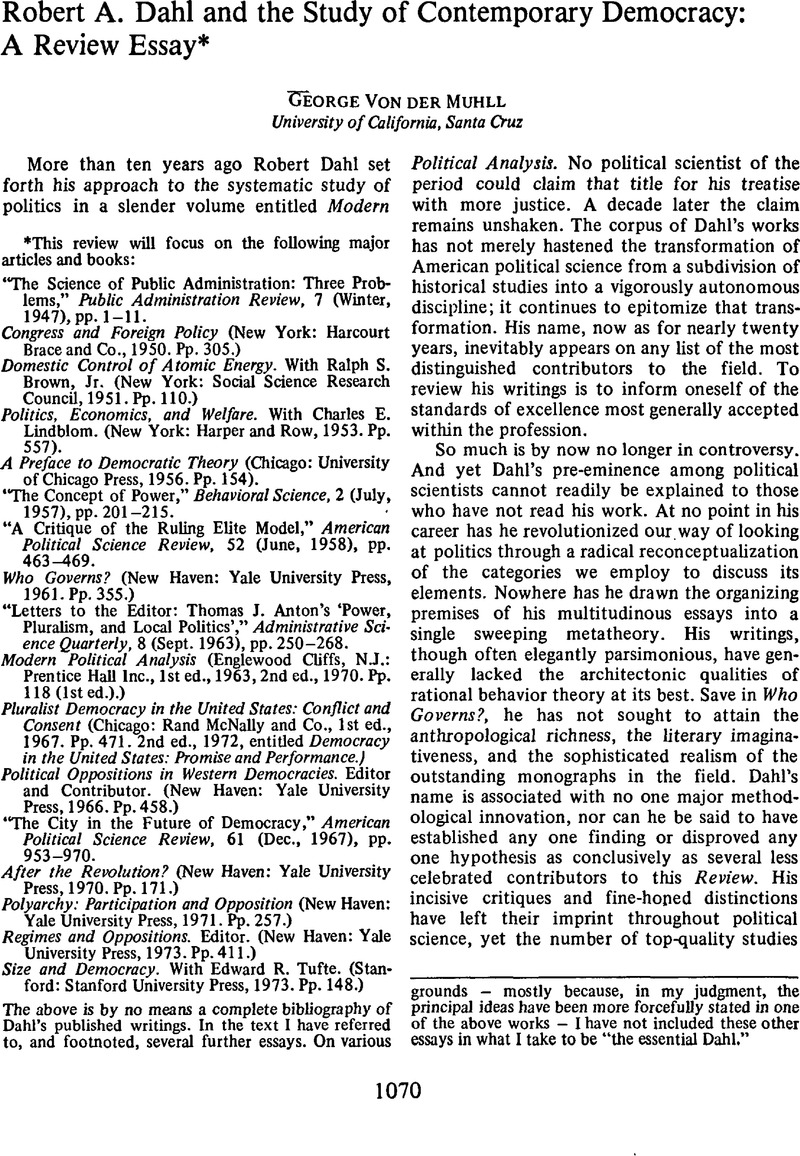

This review will focus on the following major articles and books:

“The Science of Public Administration: Three Problems,” Public Administration Review, 7 (Winter, 1947), pp. 1–11.

Congress and Foreign Policy (New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1950. Pp. 305.)

Domestic Control of Atomic Energy. With Ralph S. Brown, Jr. (New York: Social Science Research Council, 1951. Pp. 110.)

Politics, Economics, and Welfare. With Charles E. Lindblom. (New York: Harper and Row, 1953. Pp. 557).

A Preface to Democratic Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956. Pp. 154).

“The Concept of Power,” Behavioral Science, 2 (July, 1957), pp. 201–215.

“A Critique of the Ruling Elite Model,” American Political Science Review, 52 (June, 1958), pp. 463–469.

Who Governs? (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961. Pp. 355.)

“Letters to the Editor: Thomas J. Anton's ‘Power, Pluralism, and Local Polities’,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 8 (Sept. 1963), pp. 250–268.

Modern Political Analysis (Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall Inc., 1st ed., 1963, 2nd ed., 1970. Pp. 118 (1st ed.).)

Pluralist Democracy in the United States: Conflict and Consent (Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1st ed., 1967. Pp. 471. 2nd ed., 1972, entitled Democracy in the United States: Promise and Performance.)

Political Oppositions in Western Democracies. Editor and Contributor. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966. Pp. 458.)

“The City in the Future of Democracy,” American Political Science Review, 61 (Dec, 1967), pp. 953–970.

After the Revolution? (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970. Pp. 171.)

Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971. Pp. 257.)

Regimes and Oppositions. Editor. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973. Pp. 411.)

Size and Democracy. With Edward R. Tufte. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1973. Pp. 148.)

The above is by no means a complete bibliography of Dahl's published writings. In the text I have referred to, and footnoted, several further essays. On various grounds – mostly because, in my judgment, the principal ideas have been more forcefully stated in one of the above works – I have not included these other essays in what I take to be “the essential Dahl.”

1 The following periodization is based strictly on Dahl's published work, and not at all on more direct evidence as to the evolution of his scholarly interests. Hence publication dates, rather than the period of active research and writing, are treated here as controlling.

2 The locus classicus of these now gleefully belabored pretensions was, of course, the Papers in the Science of Administration, ed. Gulick, L. and Urwick, L. (New York Institute of Public Administration, 1937)Google Scholar.

3 SPA, pp. l; 2–4.

4 Cf. the similar – and, as a matter of historical record, the more memorable – formulation of this argument that same year in Simon, Herbert, Administrative Behavior (New York: Macmillan Co., 1947), chap. 2Google Scholar.

5 SPA, pp. 5–11.

6 See, e.g., his Objectivity in Social Research (New York: Pantheon Books, 1969)Google Scholar and the reference to his other works cited therein.

7 In the intervening three years, two of Dahl's least influential articles appeared in the professional journals of the period. “Worker Control of Industry,” American Political Science Review, 41 (10, 1947), 875–900 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, is essentially a summary of the debate within the postwar British Labour Party concerning the institutional implications of its commitment to increase worker participation in the management of industry. “Marxism and Free Parties,” Journal of Politics, 10 (11, 1948), 787–813 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, is a somewhat more ambitious enterprise. Nowhere else has Dahl assessed in print at such length the adequacy of Marxism as a theory of politics. The relative obscurity of the article is presumably attributable to Dahl's more extensive development in his later work of its central ideas on majority rule and the role of parties in political conflict.

8 For Dahl's formal definitions of his three value concepts, see CFP, pp. 6–7. In effect, he sided with Herman Finer in the latter's celebrated debate with Carl Friedrich on the concept of “responsibility.” See Friedrich, C., “Public Policy and the Nature of Administrative Responsibility,” Public Policy, 1940 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1940), pp. 3–24 Google Scholar; and the rejoinder by Finer, Herman, “Administrative Responsibility in Democratic Government,” 1 Public Administration Review, (Summer, 1941), 335–350 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

9 CFP, pp. 63–65, 263–264.

10 Ibid., pp. 55, 142.

11 Ibid.. pp. 180–181, 223.

12 Ibid., pp. 88, 90.

13 Ibid., p. 51.

14 A somewhat similar problem beset an article by Dahl that appeared some eight years later in this Review on the possibilities for research on the interconnections between business firms and politics. The individual points are generally well made; but most had already been made better in actual research reports, and without exceptional effort one can think of other important questions that might well have been included. This particular genre of essay seems to be falling out of favor. On the evidence provided by even so able a social scientist as Dahl, its demise does not seem indisputably regrettable. See Dahl, , “Business and Politics: An Appraisal of Political Science,” American Political Science Review, 53 (03, 1959), 1–34 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15 This change of character was seemingly quite evident to his readership. Among the ten recorded reviews of Congress and Foreign Policy, nine were published in the popular press. Henceforward, although Dahl's work has been largely lost to sight for the casual lay reader, it has regularly received widespread coverage not only in the political science journals but in the book review sections of the standard sociology and economics journals as well.

16 PEW was coauthored with Charles E. Lindblom of the Yale Economics Department. According to the Preface: “Many works appear as ‘collaborations,’ but in few can the dialectical process – in the Greek, not in the Marxist, sense – have been more heavily relied on. As much as any work by two people can do, each chapter represents the single product of two minds” (p. xxiii). I have taken the authors at their word, and shall make no effort here to detect and disentangle their individual contributions. For present purposes, this decision entails ascribing to Dahl whatever ideas appear in the book. Those interested in assessing Lindblom's contributions might wish to consult his subsequent essays on bargaining and decisional strategy, and most particularly The Intelligence of Democracy (New York: Macmillan Co., 1965)Google Scholar, although the danger of unwarranted inference is real.

17 See, e.g., the instructive series of charts in PEW, pp. 10–17, on the scope of governmental economic controls.

18 Interestingly enough, one of the most favorable reviewers was C. Wright Mills, who found in the constructive Utopian potential of the book's discussion and appraisal of alternative techniques a welcome break from the fact-bound descriptiveness of statusquo political science. See his review in the American Sociological Review, 19 (08, 1954), 495–496 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

19 Cf. Parsons, Talcott and Smelser, Neil, Economy and Society (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1956)Google Scholar. Unfortunately, Parsons has never addressed himself as directly to Dahl and Lindblom's scheme as he has to the work of several other contemporary political scientists.

20 Moreover, Dahl and Lindblom specifically assert that in their scheme the pricing system includes far more than purely competitive pricing practices. See PEW, pp. 193 ff.

21 One consequence of not working out explicit dimensions in PEW for the four politico-economic techniques is that they are certainly not exhaustive and possibly not exclusive. To judge from the chart on p. 193, and the discussion elsewhere, “pricing” appears to contain elements of both bargaining and hierarchy. And among the various control techniques not considered in the scheme, the control induced by appeal to previously accepted standards – as, for example, in much judicial decision making – is a particularly conspicuous omission. As a general rule, but without systematic critical defense of the position, Dahl has been inclined to discount heavily the efficacy of this particular form of control.

22 Ibid., pp. 227–271; 413–438; 64–88.

23 Ibid., pp. 129–226; 28–38.

24 PDT, pp. 30–31.

25 Ibid., pp. 27–29. On p. 50, in discussing the problem of intensity, Dahl does indirectly acknowledge this argument.

26 Ibid., pp. 6, 12. On p. 6, Dahl promptly reformulates the proposal through the insertion of the empirical premises that are clearly implied; nevertheless, on p. 12 he again seriously entertains the possibility that Madison was solving his argument by definition before once again dismissing the point. Madison's quotation is drawn from The Federalist, No. 47.

27 Ibid., pp. 6, 8.

28 Strictly speaking, “polyarchy” is at most, as we have seen, only one processual component among. many in the actual operation of a concrete governmental system, but Dahl here extends the term to mean any government characterized by the selection of its effective leaders through freely competitive elections. For his formal definition of “polyarchy” in this sense, see PDT, pp. 84–85.

29 Ibid., Chap.4.

30 Ibid., pp. 145–151.

31 One illustration of both the costs and gains of this approach may be found in Dahl's discussion of the U.S. Supreme Court as a protector of “minority rights.” His first formulation of the issue appeared in PDT, pp. 105–112; later he expanded the argument with additional data in “Decision-Making in a Democracy: The Supreme Court as a National Policy-Maker,” Journal of Public Law, 6 (06, 1958), 279–295 Google Scholar. In these articles he showed that, contrary to the nonem-pirical supposition of most legal scholars, the Court has not in fact effectively protected minorities from “majority tyranny,” but instead has followed the election returns – at least in most instances involving an intense and persistent congressional majority.

This finding certainly does call into question many fundamental propositions about the role of the Court within the American polity. At the same time, the leading inference is by no means conclusive. Dahl's approach tends to convert judicial decision making (as he himself quite openly acknowledges) top much into terms of “who gets what?”, with minority appeals being treated as if they were merely for discriminate benefits for that limited group alone. Leaving purely legal considerations aside, one gets little indication in such an approach of the Court's role as a teacher, and of the importance not only of the result in the instant case but of the terms in which the result is framed and justified.

32 His major conceptual essays on power from this period include “The Concept of Power” (CP; 1957)Google Scholar; “A Critique of the Ruling Elite Model” (CREM; 1958)Google Scholar; Modern Political Analysis (MPA) Chaps. 5–6; and the article on “Power” in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 12 (New York: Macmillan Co., 1968), pp. 405–415 Google Scholar. Although the I.E.S.S. article must be taken as Dahl's most recent (and therefore presumably most authoritative) statement of his views, it is by its nature rather more a survey of the literature than a detailed exposition of his own formulations. I have therefore drawn most heavily in the following discussion in the chapters in MPA, which, though less technical than the early CP article, are also in some respects much clearer. Dahl's “Critique” raises highly important but somewhat special issues that can best be discussed together with Who Governs?, his major treatise in empirical power analysis.

33 In CP, p. 203, Dahl explicitly eschews the language of causality out of deference to Hume. But since the rest of his argument makes no sense without the attribution of asymmetry to relations among people, I shall reintroduce it.

34 MPA, p. 40. Although in CP Dahl declined to distinguish between “power” and “influence” (p. 202), he found reason to do so by the time he wrote MPA. However, the distinction does not turn, as in ordinary language, on the question of intent: when A is causally responsible for altering B's behavior in ways unknown to – and immaterial to – A, or when B's causally evoked response is different from and/or contrary to A's intent, Dahl prefers to use the unilinear scalar language of “negative” influence (or – presumably – zero influence; Dahl does not really deal adequately with unintended causal relations or those to which the actors involved are indifferent) rather than qualitatively distinguishing such linkages from acts of “power” as acts of “influence.”

35 CP, pp. 203–204. Cf. the more elaborate discussion of these problems by Simon, Herbert, “Notes on the Observation and Measurement of Power,” Journal of Politics 15 (08, 1953), 500–516 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

36 CP, p. 203. Cf. Simon, , “Notes,” p. 501 Google Scholar.

37 MPA, pp. 47–49.

38 MPA, pp. 41–47.

39 To state the problem is not, of course, to preclude solutions. One might conceivably link degree of change induced to resistance overcome. Dahl's point is that one must state control relationships in ways that make clear the need for, and logical foundations of, such solutions.

40 A notably lucid short statement of the following argument may be found in Wagner, R. Harrison, “The Concept of Power and the Study of Politics,” in Political Power: A Reader in Theory and Research, Bell, Roderick, Edwards, D. V., and Wagner, R. H., eds. (New York: The Free Press, 1969), pp. 3–12 Google Scholar.

41 It is true that Dahl lists the “subjective psychological costs of compliance” as one of the five dimensions along which to compare influence (MPA, 43–44). But the few accompanying paragraphs in no way suggest the perspective outlined above.

42 An “actor,” of course, may be a corporation or a nation-state as well as a concrete person. What is at issue is not the nature of the concrete entity but the terms in which relationships are conceptualized.

43 Parsons, Talcott, “On the Concept of Political Power,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 107 (06, 1963), 232–262 Google Scholar. This essay has been reprinted in Parsons, Talcott, Sociological Theory and Modern Society (New York: The Free Press, 1967), pp. 297–354 Google Scholar, and in Bell, Edwards, and Wagner, pp. 251–284. I have used the page numbers of the latter edition.

44 Parsons, p. 251.

45 Ibid., p. 257. In this definition, “power” becomes complexly intertwined with “authority” and “obligation.” It is a curiously significant fact that one can find no sustained analysis of the latter two concepts in all Dahl's voluminous writings.

46 Ibid., pp. 277–278.

47 Personal communication, Feb. 2, 1974.

48 Since I have already discussed the most central chapters of MPA in connection with Dahl's views on power, I shall say nothing further about it in this section. The book is otherwise remarkable chiefly for the highly effective graphs, diagrams, and charts that Dahl uses to illustrate his limpid text; throughout, the book bears the stamp of a great teacher. A quite extensively revised second edition in 1970 adds a great mass of up-to-date cross-national data to the tables, but unhappily fragments and truncates a splendid chapter (Chap. 7) on the factors reducing the probability of a coercive resolution of conflicting aims.

49 Because a review of this compass must of necessity focus on Dahl rather than on his critics, citations from the latter have had to be kept to a minimum. Several of the better-known essays of that fenre have been gathered together in McCoy, Charles A. and Playford, John, eds., Apolitical Politics: A Critique of Behavioralism (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1967)Google Scholar.

50 Certain passages and chapter titles in Who Governs? contribute to the propensity of critics to read into its findings some general theses on American politics. For reasons not elaborated, Dahl wishes to argue that New Haven is in many respects “typical” of American cities (cf. the Preface and Appendix A). The second half of the book is subtitled “Pluralist Democracy: An Explanation,” and several of the succeeding chapters are premised on the contention that New Haven is a pluralist democracy in miniature. The final chapter offers a brilliant general explanation of why American democratic values prevail in political life despite evidence of apathy or hostility toward these values by the general public. Leaving the problems of circularity aside (why are there payoffs to the political elite for affirming rather than attacking these values?), one must ask on what evidence this extrapolation from New Haven is based.

51 For two exceptionally vigorous defenses, see Wolfinger, Raymond, “Reputation and Reality in the Study of Community Power,” American Sociological Revïew, 25 (10, 1960), 636–644 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Polsby, Nelson, Community Power and Political Theory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963)Google Scholar.

52 Particular formulations may run this risk by giving undue weight to peripheral issues.

53 The original – and in many ways still the best – statement of this thesis appeared in Bachrach, Peter and Baratz, Morton S., “Two Faces of Power,” American Political Science Review, 56 (12, 1962), 947–952 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

54 The crucial paragraph appears on p. 64. An even briefer resume is offered (p. 333) in Appendix B, in which he outlines the methodology of the study. On this point see Bachrach and Baratz, Part III. But one must assume that Dahl did not see the force of this criticism, for in a surprisingly ill-tempered and uncharitable response to a mildly critical article by Thomas Anton he rebutted 17 points in Anton's article but did not even refer to Anton's questions about how issues are defined. See Anton, Thomas J., “Power, Pluralism, and Local Politics,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 7 (03, 1963), 425–457, at p. 454CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and an exchange between Dahl and Anton in the same journal, 8 (Sept., 1963), 250–268.

55 Cf. Easton, David, A Systems Analysis of Political Life (New York: John Wiley, 1965), Chap. 6Google Scholar. One serious objection to the “nondecision” thesis is that it simply raises hypothetical possibilities in a manner leading potentially to an infinite regress of irrefutable speculations. Clearly, no researcher can check out every possibility that might occur to a critic; and since, by definition, “nondecisional” activities are of low visibility, there would appear to be no control on this process. Indeed, it might be said that the issue between Dahl and his critics is how far to push back the defining boundary between the “political” and “nonpolitical” stages of a developing issue, since Dahl's method clearly does allow for the suppression of alternatives within the political arena before an authoritative decision is reached.

56 In 1971 Dahl prepared a second edition under the title Democracy in the United States: Promise and Performance. The change in title was deliberate. On the one hand, Dahl sought to get away from the ambiguities – and the question-begging controversy – over “pluralism”; on the other, he wished to stress more explicitly the gap between the traditional ideals of democracy and the current record of the American government (which he calls, harking back to PEW, a polyarchy” in order to take direct account of the unequal distribution of power within the system). The greater concern for evaluation carries over into the addition of several preliminary chapters on “Democracy as an Ideal and as an Achievement” and a final chapter assessing the performance of the American polyarchy; none contain ideas more novel than that great inequalities of wealth and income remain in the country and that racial discrimination violates American ideals.

57 Another theme of some interest is Dahl's ambivalence toward reduced political participation. Like all attentive readers of empirical survey research reports on civic orientations, he is struck by the fact that most “extremists” are nonvoters and that a significant fraction of nonvoters hold “extreme” orientations. This perspective emerges most clearly in a controversy with Walker, Jack L. over “The Elitist Theory of Democracy,” American Political Science Review, 60 (06, 1966), 285–305 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. It is a frustrating controversy: Walker appears to brush aside the evidence referred to above in his highly normative structures, while Dahl is more convincing in his general assertion that he favors an increase in some kinds of participation than in a long footnote (No. 13) designed to show that Walker's characterizations have no foundation.

58 The one conspicuous exception to this generalization is the cross-nationally comparative structure of Politics, Economics and Welfare. But the multitudinous references to planning experiences in Great Britain, Sweden, the Netherlands, New Zealand, et al., seem chosen (save in the case of Great Britain) at a quite superficial level for their illustrative effect: the book neither stands not falls on their validity. One suspects that Lindblom's independent contributions as an economist were particularly important here.

59 Eckstein, , American Political Science Review, 61 (03, 1967), pp. 158–160 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Verba, , “Some Dilemmas in Comparative Research,” World Politics, 20 (10 1967), 111–127, at p. 118 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 POWD, pp. 375–376, 392, 395. The general theoretical argument was, of course, already advanced in its essentials in his PDT, Chap. 4, and in Downs, Anthony, An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York, Harper & Row, 1957), pp. 117 ffGoogle Scholar.

61 Even more striking is Dahl's anticipation, at the high-water mark of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, of disenchantment among “young people” and intellectuals with the “remote and bureaucratized” state of the “democratic Leviathan” (POWD, pp. 399–400). In these final pages of his Epilogue to the volume, Dahl faintly foreshadows the concerns that were soon to lead to his systematic exploration of the ultra-democratic critique of polyarchy in After the Revolution?

62 A few recent studies, on which Dahl himself draws heavily, offer statistical correlates of various categories of political regimes, including democracy, but do not purport to relate these findings with any degree of complexity to the distinctive institutions and processes of the democratic order.

63 Polyarchy, pp. 1–5.

64 To me, at least, an unsatisfactory element in Dahl's delineation of his dependent variable is his insistence on employing two dimensions, one of which is patently more important than the other. “Competitive oligarchies” (e.g., Britain, 1832–1884) shade indistinguishably along a quantitative continuum into full polyarchies, whereas only Communists and Fascists would seriously contend that “inclusive hegemonies” resemble polyarchies in any critically significant sense. The problem in attributing a formally equal weight to public contestation and inclusiveness can be seen at its logically absurd extreme in Dahl's hesitancy at including Switzerland among the world's 25 polyarchies because it did not at that time grant suffrage in national elections to the female 50 per cent of its adult population (Appendix B, p. 246). Thus his diagram (p. 6) of “two theoretical dimensions of democratization” is characteristically ingenious, but utterly misleading in its formal implication that countries far along the 15° line (high in inclusiveness, low in public contestation), can properly be regarded as no farther from the 45° line than those far along the 75° line (low in inclusiveness, but high in public contestation).

65 Polyarchy, pp. 132–140.

66 Ibid., Chap. 6.

67 Thus, in his discussion of economic development, Dahl leaves himself no room to examine the independently important factor of rate of growth. Moreover, his insistence (Polyarchy, pp. 76–80) that the educational and structural requisites of an “advanced economy” generate demands for a competitive political order seems to grow mainly out of the exigencies of his general argument. It scarcely constitutes a refutation of writers who, taking into account the enhanced opportunities for deliberately controlling socialization, for monitoring increasingly sophisticated informational networks, for pyramiding economic and coercive resources, and for buying off potential dissidents, have argued otherwise in the case of the now relatively affluent Soviet and East European Communist nations.

68 See Mill, J. S., A System of Logic (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1957), pp. 575–577 Google Scholar.

69 Dahl is, of course, aware of this problem. He frequently diagrams the interactive potential of a complex set of variables – see e.g., the very well worked out models on pp. 56, 79, and 91. The difficulty is that to quantify them for each country, given the state of other theoretically relevant variables for that country and with due attention to threshold effects and emergent properties, would render the approach unmanageably difficult.

70 One approach that trades some of the universalism and ready testability of Dahl's propositions for a richer interactive analysis is illustrated by such works as Moore's, Barrington Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966)Google Scholar and Huntington's, Samuel P. Political Order in Changing Societies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968)Google Scholar, in both of which a set of not very rigorously formulated general models is evolved out of a comparative study of the sources of fragility and strength of democracy (and other forms of government) in particular countries. A notable feature of Huntington's approach is that it points to the creative potential of political leaders and political movements as historical agents combining the specific resources of nations to build political orders – a potentiality that Dahl's cross-sectional categorical analysis obscures despite his chapter on the political beliefs of political activists.

71 RO, p. 5. Of course, the differential impact of cross-cutting cleavages in these nations can be dealt with through introducing such flexible contextual concepts as the catalytic significance of varying political cultures; but Dahl does not enter into such complexities. Instead, at the bottom of this same page, he alternately deploys cross-cutting and reinforcing cleavages as a means of suggesting why political cohesiveness is reduced to a minimum in African politics.

72 “CFD,” p. 964.

73 Loc. cit.

74 “CFD,” p. 955.

75 Ibid., p. 962.

76 Ibid., pp. 961–962. Cf. his earlier exposition of the problems of co-determination in British industry (note 7 above).

77 Ibid., p. 967. A list of cities in contemporary America providing such opportunities would make interesting reading. It would include such centers of civilization as Fresno (California), Amarillo (Texas), Peoria (Illinois), Gary (Indiana), Scranton (Pennsylvania), and (of course) New Haven (Connecticut), while clearly excluding such metropolises as Rochester (New York), Birmingham (Alabama), Tulsa (Oklahoma), and Wichita (Kansas) on grounds of size.

78 Though published in 1973 – three years after the “Yale Fastback” (After the Revolution?) discussed below – the first draft of SD was written in 1967 during a stay at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto. It seems accordingly appropriate to discuss SD in direct conjunction with “CFD,” which draws heavily on ideas developed during the course of research for the larger volume. Since no effort is made to distinguish the contributions of the two co-authors, I have here attributed to Dahl full responsibility for all statements appearing in the book.

79 SD. pp. 61–65.

80 Ibid., 141, 142. A further virtue of the book is that it contains, in a discussion of the relation of size to system capacity, the most enviable sentence in the spectrum of Dahl's vast writings: “A small-democracy man may put his bets on the mouse outlasting the elephant and the whale; doubtless he will find takers among the Chinese, Russians, and Americans” (p. 111).

81 On the limited conclusions that can be drawn from cross-national comparisons regarding size see, e.g., SD, pp. 52–53. Accepting this limitation, several students of Heinz Eulau at Stanford – among them Gordon Black – have taken up systematic empirical investigation of the consequences of size for local government inside the United States. Cf. also Verba, Sidney and Nie, Norman (both formerly of Stanford), Participation and Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), pp. 231–243 Google Scholar, although it treats Dahl's theme only briefly.

82 AR?, p. 55.

83 Cf. note 75.

84 Technology has no bearing on the problem; for while advanced technology can link together people who are spatially dispersed, it cannot – or at least, cannot yet – reduce the time required by any one participant to process, assimilate, and respond to the ideas conveyed by the immediately preceding speaker, 1 and therefore cannot overcome the limits to the number of sequentially interdependent exchanges that can take place within any given period of time.

85 AR?, pp. 59–67, 82–88.

86 For one example among many of the use of rational behavior analysis to identify the emergent properties of large-scale interaction, see Olson, Mancur, The Logic of Collective Action (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965)Google Scholar. On the systemic properties of power, see Parsons, “On the Concept of Political Power,” on regime transformations, see David Easton, Systems Analysis of Political Life. Cf. fn. 55.

87 See Schumpeter, Joseph, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943), Part IVGoogle Scholar. Dahl shows somewhat greater optimism than Schumpeter regarding the possibilities of rational self-clarification through participation in political discussion.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.