No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

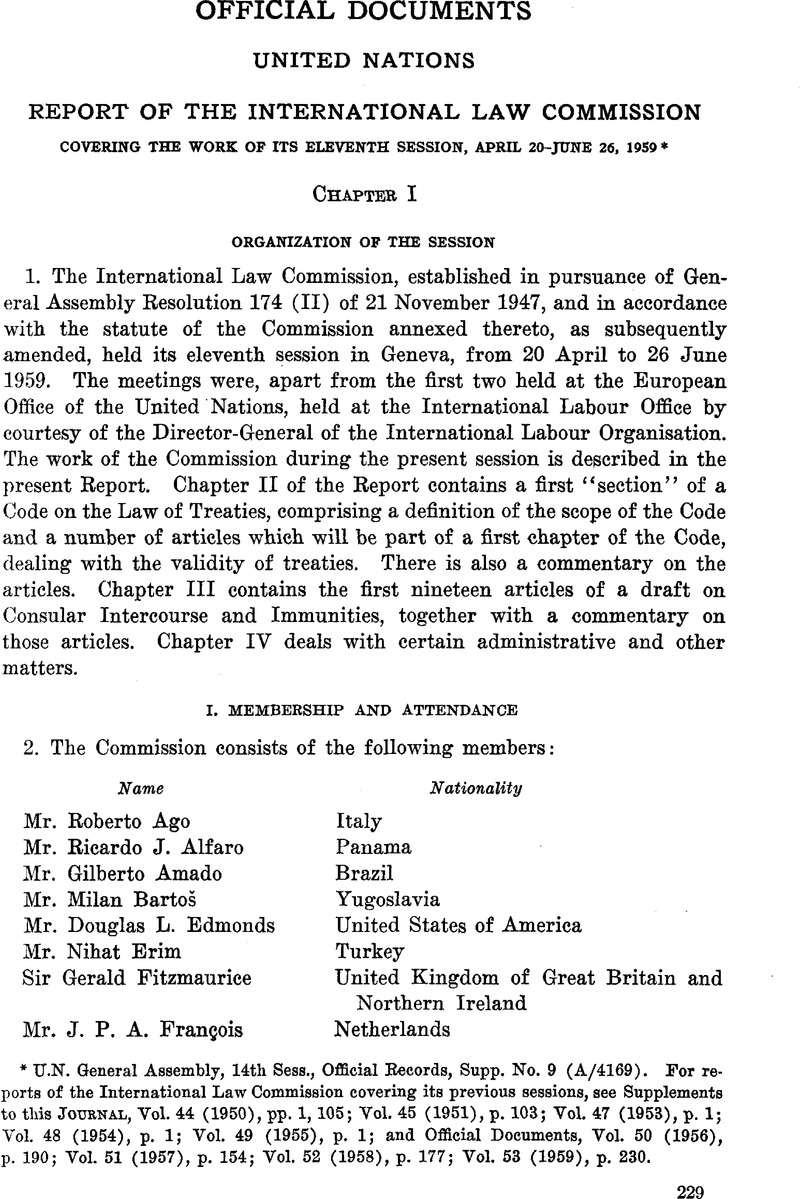

U.N. General Assembly, 14th Sess., Official Eeeords, Supp. No. 9 (A/4169). For reports of the International Law Commission covering its previous sessions, see Supplements to this JOURNAL, Vol. 44 (1950), pp. 1,105; Vol. 45 (1951), p. 103; Vol. 47 (1953), p. 1; Vol. 48 (1954), p. 1; Vol. 49 (1955), p. 1; and Official Documents, Vol. 50 (1956), p. 190; Vol. 51 (1957), p. 154; Vol. 52 (1958), p. 177; Vol. 53 (1959), p. 230.

1 Official Records of the General Assembly, 13th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3859), par. 57.

2 Ibid., par. 61.

3 Ibid., 4th Sess., Supp. No. 10 (A/925).

4 Ibid., pars. 19-20.

5 Ibid., 5th Sess., Supp. No. 12 (A/1316).

6 Ibid., 6th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/1858).

7 Ibid., 7th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/2163).

8 Ibid., 8th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/2456).

8a Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1951, Vol. I (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1957. V. 6, Vol. I ) , p. 136.

9 Official Records of the General Assembly, 10th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/2934).

10 These are respectively on the topics of the framing, conclusion and entry into force of treaties; the termination of treaties; essential or substantive validity; and effects as between the parties (operation, execution and enforcement). They are to be found in A/CN.4/101, A/CN.4/107, A/CN.4/115, and A/CN.4/120. Further reports on effects in respect of third states, and on the interpretation of treaties, are in preparation.

11 In addition to the reports at present before the Commission, and others in preparation or contemplation (see footnote 10 above), the topic of treaties forms a branch of certain other subjects, e.g. the effect of war on treaties; treaties and state succession, etc. It is by no means clear that a code on treaty law should not cover these, although they probably belong more properly to the other topics concerned.

12 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1956, “Vol. I I (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1956. V. 3, Vol. II ) , p. 106.

13 There will be signature alone in the case of agreements expressed to take effect on signature, or in the case of certain classes of instruments, such as exchanges of notes, agreed minutes, memoranda of understanding, etc., which are normally [not] subject to ratification unless this is expressly provided for.

14 Depending on the character and terms of the treaty, entry into force may coincide with ratification or may take place later.

15 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1956, “Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1956. V. 3, Vol. II), pp. 106-107.

16 See, in addition to the material in pars. 9 and 10 of the present report, Sir Hersch Lauterpacht's first report (A/CN.4/63), par. 3 of the “Note” to his Art. 2.

17 Series A/B, No. 41, p. 47.

18 The English text of the judgment is probably a translation from an original French text. A better English rendering would be “such engagements may be assumed in the form of,” or better still, simply “may take the form of treaties, etc.“

19 Introduction à l'étude du droit international, pp. 33-34.

20 A/CN.4/63, note to Art. 2, p. 39.

21 See on this subject the commentaries to Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice's second report (A/CN.4/107), pars. 115, 120, 125-128 and 165-168; his third report (A/CN.4/115), pars. 90-93; and fourth report (A/CN.4/120), pars. 81 and 101.

22 See footnote 13. This matter will be more fully considered in connexion with the articles on ratification.

23 A/CN.4/63, p. 38, par. 3.

24 In his article ‘’ The Names and Scope of Treaties'’ (American Journal of International Law, 51 (1957), No. 3, p. 574), Mr. Denys P. Myers considers no less than thirty eight different appellations. See also the list given in Sir Hersch Lauterpacht's first report (A/CN.4/63), par. 1 of the commentary to his Art. 2. In addition to those mentioned in pars. (1) and (2) of the commentary to the present article, the following may be mentioned: “ charter , “ “covenant,” “ pact , “ “general act,” “ statute , “ “con cordat,” modus Vivendi,” “ agreed minute,” “ articles , “ “arrangement,” “exchange of letters,” etc.

25 An unqualified rule that all instruments embodying international agreements are treaties might suggest that all such agreements without exception require ratification effected or authorized by the legislature, which is not the case (or alternatively it is a matter to be determined by the internal law of each individual state).

26 Series A/B, No. 53, p. 69 et seq.

27 For instance there cannot be any signature of an oral agreement—or else, ipso facto, it becomes a written one.

28 An exchange of notes may in a sense be said to constitute an example of this, but usually the notes expressly refer to one another. Such an express reference is not however essential to constitute an agreement. For instance, any two declarations under the “Optional Clause,” accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, insofar as they both cover the same disputes or class of disputes, may be regarded as constituting jointly an agreement to have recourse to the Court in regard to the disputes specified, or if a dispute of that class arises between the parties.

29 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1956, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1956. V. 3, Vol. II ) , p. 117.

30 Even here however, a petitio principii may be involved, for the pactum is only servandum if it is a pactum —i.e. already an international agreement.

31 However, it could perhaps be said (according to one school of thought) that this is a case where international law does govern, but does so by an express reference of the matter to some system of private law.

32 If several states were involved, together with one or more private entities, the instrument might operate as a treaty purely in the relations between the states parties to it.

33 A/CN.4/115, Art. 8 and the commentary thereto.

34 See the first Lauterpacht report (A/CN.4/63), par. 4 of the commentary to Art. 1.

35 It should be noticed that the Commission was not attempting to provide a strict logical definition of a treaty or international agreement, but (as the title to Art. 2 implies) aimed merely at describing its general meaning. In this field, definitions are apt to run into difficulties from the standpoint of strict logic. For instance, as regards the phrase to which the present footnote relates, it might be objected that it really avoids the issue, or only leads to circularity, for it necessitates an enquiry as to (or definition of) what agreements are in fact governed by international law. The meaning is nevertheless reasonably clear.

36 In this and the two succeeding paragraphs the numbering of the articles is not given, as it is liable to change, or else has not been determined because the Commission has not yet considered the articles concerned.

37 Drawn up in the Sixth Committee of the General Assembly at its Third Session, Paris, 1948.

38 As, for instance, the International Labour Organisation.

39 Both points are exemplified by the Law of the Sea Conference, convened by the General Assembly and held at Geneva in 1958, to which a number of states not Members of the United Nations were invited and came.

40 That is, apart from the special case mentioned in Art. 15, par. 1 (a).

41 They would, however, still require specific full powers to sign any resulting treaty.

42 Series A/B, No. 53, p. 71.

43 Italics added by the Commission.

44 Official Records of the General Assembly, 13th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3859), p. 12; see also Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1958, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 58. V. 1, Vol. II ) , p. 90.

45 It can, of course, be argued that the law of treaties presupposes the existence of a treaty, and must therefore take its point of departure from the completed treaty actually in force. This would, however, exclude such matters as signature and its effects, ratification, accession, reservations, entry into force, and other matters, all of them traditionally regarded as part of the law of treaties.

46 The rule of the simple majority vote for procedural decisions is universally admitted; but the discussion here relates to substantive decisions—in particular those leading to the adoption of texts.

47 It is less important only because, in the case of these instruments, it is easier to infer with reasonable certainty what the intention is. Thus it is fairly clear that unless something different is indicated, an exchange of notes takes effect on the date of exchange, whether this is stated or not.

48 That is to say, less use is made of formal clauses specifically devoted to providing for ratification, entry into force, duration, etc., and more is left to the play of inference or indirect indication.

49 The numbering is left blank as the Commission has not yet considered all the articles involved.

50 See the text of Art. 9, and see further below, where it is explained that the other aspects and effects of signature have tended to mask its authenticating aspect.

51 The practice of the United Nations for purposes of authentication is to use the latter two methods specified in par. 1 of Art. 9, rather than the first alternative of initialling. The custom of initialling has never been used in the United Nations for the purposes of authenticating the text of a multilateral convention. Initialling for the purposes of authentication has been supplanted, in the more institutionalized treatymaking processes of the United Nations, by such standard machinery as the recorded vote on a resolution embodying or incorporating the text, or by incorporation into a final act. As stated in par. (4) of the above commentary, any subsequent alteration of a text authenticated by these means would be, in effect, the drawing up of a new text, itself requiring authentication by the same or other recognized means.

52 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1950, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1957. V. 3, Vol. II ) , pp. 233-234.

53 Theoretically, a treaty might only after authentication by signature, be embodied in a resolution of an international organization and be recommended for accession by members not having signed it. Professor Brierly mentions such a possibility.

54 See footnote 49.

55 Such cases are infrequent but have occurred. The intention may be inferred from the instrument as a whole or from the surrounding circumstances.

56 At present, when a telegraphic authority, pending the arrival of written full powers, would usually be accepted (see Art. 15 below, and the commentary thereto), the need for recourse to initialling on this ground ought only to arise infrequently.

57 See footnote 49.

58 For instance, heads of states, heads of governments, and foreign ministers would normally be competent authorities.

59 For instance, by his office, e.g. ‘’ Our Ambassador at … , for the time being.''

60 In bilateral or other restricted negotiations, the full-powers will normally be examined by the protocol or treaty departments or sections of the respective foreign ministries or embassies. In the case of international conferences, a credentials committee will be set up, or else the examination will be entrusted to the secretariat or bureau of the conference.

61 The Commission had not reached this part of the work at the end of the present session.

62 Art. 14 of the Convention on the Pan-American Union, adopted at Havana on Feb. 18, 1928, provides as follows: “The present Convention shall be ratified by the signatory States and shall remain open for signature and for ratification by the States represented at the Conference and which have not been able to sign it . ‘ ‘ The Convention on Treaties, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention on the Condition of Aliens, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention on Diplomatic Agents, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention on Consular Agents, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention on Maritime Neutrality, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention relating to Asylum, adopted Feb. 20, 1928; the Convention on the Rights and Duties of States in the Event of Civil War, adopted Feb. 20, 1928, all contain a slightly different final clause which merely states that after signature it shall be subject to ratification by the signatory states. There is no time limit specifically imposed on signature. All the above-mentioned conventions were adopted at the Sixth Pan-American Conference held at Havana.

63 Official Records of the General Assembly, 4th Sess., Supp. No. 10 (A/925), pars. 16 and 20.

64 Ibid., 10th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/2934), par. 34.

65 Ibid., 11th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3159), par. 36.

66 Ibid., 12th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3623), par. 20.

67 Ibid., 13th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3859), par. 56.

68 Ibid., par. 57.

69 Ibid., par . 64.

70 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1957, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1957. V. 5, Vol. II ), p. 80, par. 80.

71 Ibid., par. 84.

72 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1957. V. 5, Vol. II ) , p. 91.

73 A/CN.4/SB.513, par. 54; A/CN.4/SB.514, par. 25.

74 A/CN.4/SR. 513, par. 62.

75 A/CN.4/8E.517, par. 2.

76 See A/CN.4/L.84, Art. 13.

77 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1957, Vol. II (U.N. pub., Sales No.: 1957. V. 5, Vol. II ) , Doc. A/CN.4/108.

78 Official Records of the General Assembly, 13th Sess., Supp. No. 9 (A/3859), par. 51.

79 Ibid., par. 71.