Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

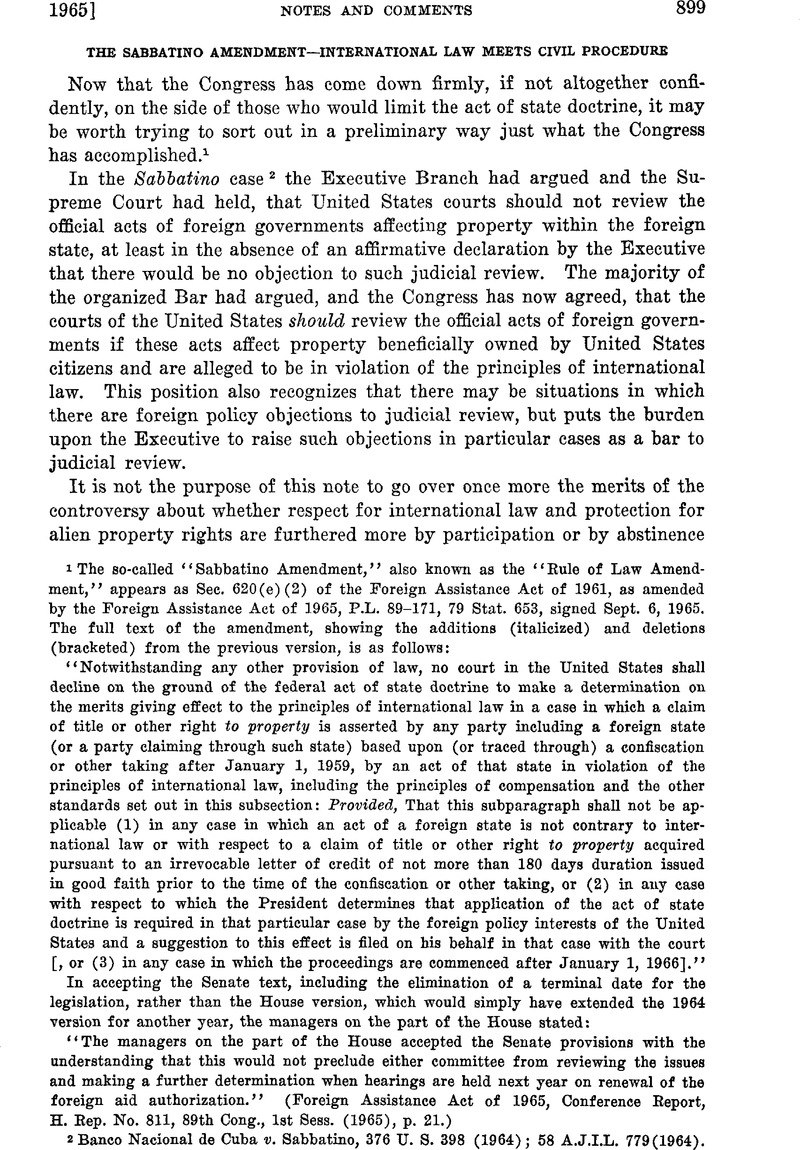

1 The so-called ‘ ‘ Sabbatino Amendment,'’ also known as the ‘ ‘ Rule of Law Amendment,” appears as Sec. 620(e)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1965, P.L. 89-171, 79 Stat. 653, signed Sept. 6, 1965. The full text of the amendment, showing the additions (italicized) and deletions (bracketed) from the previous version, is as follows: “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no court in the United States shall decline on the ground of the federal act of state doctrine to make a determination on the merits giving effect to the principles of international law in a case in which a claim of title or other right to propertyis asserted by any party including a foreign state (or a party claiming through such state) based upon (or traced through) a confiscation or other taking after January 1, 1959, by an act of that state in violation of the principles of international law, including the principles of compensation and the other standards set out in this subsection: Provided,That this subparagraph shall not be applicable (1) in any case in which an act of a foreign state is not contrary to international law or with respect to a claim of title or other right to propertyacquired pursuant to an irrevocable letter of credit of not more than 180 days duration issued in good faith prior to the time of the confiscation or other taking, or (2) in any case with respect to which the President determines that application of the act of state doctrine is required in that particular case by the foreign policy interests of the United States and a suggestion to this effect is filed on his behalf in that case with the court [, or (3) in any case in which the proceedings are commenced after January 1, 1966].” In accepting the Senate text, including the elimination of a terminal date for the legislation, rather than the House version, which would simply have extended the 1964 version for another year, the managers on the part of the House stated: “The managers on the part of the House accepted the Senate provisions with the understanding that this would not preclude either committee from reviewing the issues and making a further determination when hearings are held next year on renewal of the foreign aid authorization.” (Foreign Assistance Act of 1965, Conference Eeport, H. Eep. No. 811, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965), p. 21.)

2 Banco Nacional de Cuba v.Sabbatino, 376 U. S. 398 (1964) ; 58 A.J.I.L. 779(1964).

3 This writer's views, as elsewhere stated, are to the contrary. See Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae in Sabbatino; Book Beview, 77 Harvard Law Bev. 388 (1963); 5 Harvard International Law Club Journal 215 (1964).

4 Throughout this paper it is assumed that there has been no Presidential determination that application of the act of state doctrine is required in the case under discussion.

5 E. g.,Silsbury v.McCoon, 3 N. Y. 379 (1850).

6 See, e.g.,the cases cited in Sabbatino, 376 U. 8. at 421, note 21.

7 For two older New York cases taking opposite views of this question, compare Edgerly v.Bush, 81 N. Y. 199 (1880) with Goetschius v.Brightman, 245 N. Y. 186 (1927).

8 See 376 U. S. at 438.

9 See A.L.I. Restatement of Conflicts of Law, Second, Sec. 215 (immovable property); Sees. 254a and 257 (movable property) (Tent. Draft No. 5, 1959).

10 The Senate Committee report states on this point: “This paragraph (e)(2) refers to ‘the principles of international law, including the principles of compensation and the other standards set out in this subsection.’ This reference is to the provisions of section 620(e)(1) which define the obligations of international law to include ‘speedy compensation … in convertible foreign exchange equivalent to the full value’ of the property affected.” (Foreign Assistance Act of 1965, Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, S. Eep. No. 170, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965), p. 19.) Query whether this resolves the doubts expressed on this point by the Supreme Court, 376 U. S. at 428-430.

11 The most concise definition of a quasi in remaction appears in the Introductory Note to Chapter 9 of the A.L.I. of Judgments (1942). In pertinent part it reads as follows: “There are two types of proceedings quasi in rem. In both of them the jurisdiction of the court is based on power over a thing and the effect of the judgment is to affect interests of particular persons in the thing. “ I n the second type the plaintiff is not seeking to establish a pre-existing interest in the thing but is seeking to enforce a personal claim against the defendant by applying the thing to the satisfaction of the claim. Of this type are actions to recover damages for breach of contract or for tort begun by attachment or garnishment or creditor's bill, where the court has no jurisdiction over the person of the defendant but has jurisdiction over a thing belonging to the defendant or over a person who is indebted or under a duty to the defendant.“

12 Foreign Assistance Act of 1964, P.L. 88-633, 78 Stat. 1009 (1964), Sec. 301(d)(4). The text may be seen by referring to the changes indicated in note 1 above.

13 Though the date fixed in the statute coincides with the coming to power of Castro and much of the discussion has been with property taken in Cuba in mind, we may for the time being disregard the possibility that the foreign government is Cuba, since all property in which Cuba or Cuban nationals have an interest, and all property originating in Cuba, has been prohibited from entry into the United States since early 1962. Proclamation No. 3447, Embargo on All Trade with Cuba, 27 Fed. Beg. 1985 (1962); Cuban Assets Control Begulations, 31 C.F.E. §§ 515.101-808 (Supp. 1964).

14 Prom the text, it might be thought that the phrase ‘ ‘ claim of title or other right” related only to the party claiming by virtue of the confiscation. But this appears to be too literal a reading. There is no evidence that the 1964 conference sought to make a substantive change on this point from the text as passed by the Senate, which said simply “no court in the United States shall decline to make a determination on the merits … in a case in which an act of a foreign state … is alleged to be contrary to international law… . “ Compare Foreign Assistance Act of 1964, Conference Report, H. Eep. No. 1925 (88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964)), pp. 3, 16, with Eeport of Committee on Foreign Relations, S. Eep. 1188, Part 1 (88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964)), pp. 24, 37.

15 American Hawaiian Ventures Inc., formerly Hawaiian Sumatra Plantations Ltd. v.M. V. J. Latuharhary and Djakarta Lloyd Lines, Admiralty No. 65-687-WB, TJ.S.D.C, So. Disk Cal. Decided May 13, 1965.

16 The same plaintiffs made a similar attempt two weeks later when the same vessel arrived in Newark, New Jersey. Admiralty No. 576-65, U.S.D.C., Dist. N. J. At this writing the second case had not been decided.

17 Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, note 10 above, p. 19.

18 Foreign Assistance Act of 1965, Hearings before Committee on Foreign Affairs, Part IV, p. 607, Testimony of Mr. Cecil J. Olmstead (89th Cong., 1st Sess., 1965). Two pages further on in the Hearings the following colloquy appears between Mr. Olmstead and Congressman Cameron: “Mr. Cameron: … “Mr. Olmstead, back on Mr. Fraser's line of questioning. I am confused. I have the feeling from this particular amendment that if X country expropriates the oil industry in violation of law and does not provide adequate compensation, and the oil belongs to Texaco, then there is a shipment of timber into New York harbor which has also been nationalized at some previous date, couldn't you attach the timber and sue as long as it was the property of the other sovereign state! “Mr. Olmstead.Under the facts you have set forth, this would not be a case in which the company to which you made reference was asserting a claim of title or other right in that particular case with regard to that commodity. “Mr. Cameron.This is entirely different than the amendment as it has been explained to me by proponents of your particular committee in the past. It has been explained under this provision that they claim it would have a right to a certain claim against any property belonging to the other sovereign state. I would assume that would not include their Embassy, but virtually anything else.“

19 Letter from Acting Legal Adviser, Department of State, to Acting Attorney General, May 19, 1952, 26 Dept. of State Bulletin 984 (1952).

20 Hellenic Lines Ltd. v.Moore, 345 F . 2d 978 (D.C. Cir., March 25, 1965; digested below, p. 927.

21 Oster v.Dominion of Canada, 144 F. Supp. 746 (N.D.N.Y., 1956), digested in 50 A.J.I.L. 962 (1956); aff'd 238 F. 2d 400 (2d Cir., 1956); cert, denied, 353 U. S. 936 (1957); Purdy Co. v.Argentina, 333 F . 2d 95 (7th Cir., 1964), digested in 59 A.J.I.L. 162 (1965); cert, denied, 379 TJ. S. 962 (1965).

22 E.g.,New York Civil Practice Law and Rules (7B McKinney's Consol. Laws Ann.), Sees. 302, 313. Dlinois Civil Practice Act (HI. Eev. Stat., Ch. 110), Sees. 16, 17.

23 Fed. E. Civ. P . 4 ( d ) , 4(i) as amended, effective July 1, 1963. See also Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules, printed in 28 tJ.S.C. App. following Rule 4 (Cum. Supp. V, 1964).

24 See Victory Transport Inc. v.Comisaria de Abastecimientos y Transportes, 336 F. 2d 354 (2d Cir., 1964), digested in 59 A.J.I.L. 388 (1965), where the assimilation of the State service of process authorization came through Sec. 4 of the Federal Arbitration Act, 9 TJ.S.C. §4, which in turn incorporates the Federal Rules.

25 New York and Cuba Mail S.S. Co. v.Republic of Korea, 132 P. Supp. 684 (S.D.N.T., 1955), digested in 50 A.J.I.L. 137 (1956).

26 See, for a perhaps outdated view, Kingdom of Roumania v.Guaranty Trust Co., 250 Fed. 341 (2d Cir., 1918): “ I t seems to us manifest that the Kingdom of Roumania in contracting for shoes and other equipment for its armies was not engaged in business but was exercising the highest sovereign function of protecting itself against its enemies.” An Italian court, on essentially the same set of facts, reached the opposite result a few years later. Stato di Romania v.Trutta, 1926, I Monitore dei Tribunal! 288; 26 A.J.I.L. Supp. 629 (1932).

27 Without addressing itself to the distinction between commercial and public acts, one lower court in Pennsylvania recently refused to grant immunity from suit to the Republic of “Venezuela in an action brought to secure damages for an alleged expropriation of certain mineral rights in that country. The action was commenced by attachment of a state-owned merchant vessel but the vessel was subsequently released. Chemical Natural Besources, Inc. v.Republic of Venezuela, Ct. of Com. Pleas, Phila. Co., Pa., Sept. Term, 1963, No. 2048 (Dec. 18, 1964; opinion May 13, 1965). At this writing, the case is on appeal to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (Jan. Term, 1965, No. 141).

28 Victory Transport Inc. v.Comisaria de Abastecimientos y Transpotes, 336 F. 2d 354 (2d Cir., 1964) digested in 59 A.J.I.L. 388 (1965); cert, denied, 381 U. S. 934 (June 1, 1965).

29 In fairness, it was sufficient for the court to rule on the suit before it, involving a claim for damages arising out of a charter party.

30 See, for example Flota Maritima Browning de Cuba v.M.V. Ciudad de la Habana, 335 F. 2d 619 (4th Cir., 1964), digested in 59 A.J.I.L. 161 (1965). While the majority decided against immunity in that case on the ground that there had been a waiver, the dissenting judge indicated that he was not impressed by the tendency to restrict immunity: “ I am not unaware of the able administrative commentaries to the effect that the rule of the Berizzi case [271 IT. S. 562 (1926), expressing the doctrine of absolute immunity even'for a merchant vessel against a commercial claim against the vessel] is no longer the attitude of the V. 8. Department of State… . But nowhere do I find the Supreme Court professing any change in its outlook, and I would await its own articulation, words for me preferable even to a scholar's forecast.” (335 F. 2d at 628-629.)

31 The Supreme Court asked the Solicitor General for his views on the petition for certiorari in Victory Transport, but then denied certiorari, despite the urging of the Solicitor General to take the case if the Court viewed it as presenting directly the question of the scope of the doctrine of sovereign immunity. The petitioner had framed the question in such a way as to focus only on the questions of consent and service of process.

32 See Stephen v.Zivnostenska Banka, National Corp., 15 A.D. 2d 111, 222 N.T.S. 2d 128 (App. Div., 1st Dept., 1961), digested in 56 A.J.I.L. 848 (1962); aff'd 12 N. Y. 2d 781, 235 N.Y.S. 2d 1 (1962).

33 See citations to A.L.I. Restatement of Conflict of Laws, Second, note 9 above.