I. Developments in Antarctic Tourism 652

II. Regulatory Responses and Outstanding Policy Questions 654

A. Antarctic Governance 654

B. ATCM Discussions on Antarctic Tourism and Concerns Expressed 656

C. Regulatory Responses of the ATCM Since the Adoption of the Protocol 658

D. Outstanding Policy Questions 658

III. The Difficulty of Reaching Consensus 664

A. The Consensus Rule in Antarctic Governance 664

B. Antarctic Tourism: The Difficulty of Reaching Consensus 666

C. Possible Reasons for Absence of Consensus 666

IV. The Consequence of the Absence of Consensus: Decision Making By Non-decision making 668

V. Strengthening ATCM Decision Making 669

A. Consultative Parties Getting Impatient: Decision to Start Negotiations on a Comprehensive and Consistent Framework for the Regulation of Antarctic Tourism 669

B. Options for Strengthening Decision Making 670

1. Enhanced Deployment of Tools to Strengthen “Consensus Making” as a Component of the Duty to Cooperate in Good Faith 670

2. Exceptions to the Consensus Rule in Specifically Defined Situations 671

3. Improving the Functioning of the Committee for Environmental Protection 672

4. Enhancing Involvement of High-Level Officials or Politicians (e.g., “Ministerial on Ice”) 674

5. Intensified Collaboration Among Consultative Parties as an Alternative or Possible First Step Toward ATCM Decision Making 674

VI. Conclusions 675

I. Developments in Antarctic Tourism

Antarctic tourism started in the 1960s and until the mid-1980s the average numbers remained below one thousand tourists per season.Footnote 1 Since the adoption of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Protocol)Footnote 2 in 1991, the number of tourists visiting AntarcticaFootnote 3 has increased from almost 6,500 in the 1991–1992 season to 74,401 tourists for the 2019–2020 season.Footnote 4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers dropped dramatically, but the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO)Footnote 5 has reported that in the 2022–2023 season more than 104,897 tourists have visited the Antarctic.Footnote 6 This is a more than 40 percent increase compared to the pre-pandemic 2019–2020 season. In this five-year period, the number of SOLAS tourist vessels active in the Antarctic region increased from thirty-seven to fifty, a more than 35 percent increase.Footnote 7 IAATO's tourist number estimate for the next season (2023–2024) is 118,089,Footnote 8 which means a further growth of 12.5 percent in one year.

Most tourists (> 60 percent) travel to Antarctica on small- and mid-sized ships, making landings at various sites in the Antarctic Peninsula region on a seven- to ten-day trip.Footnote 9 Another relatively large group of tourists aboard ships with a capacity of over five hundred passengers do not make landings in Antarctica and have a “cruise only” experience (> 30 percent). Smaller groups (together < 10 percent) fly to Antarctica to participate in a cruise (“fly-sail operations”),Footnote 10 or travel to Antarctica onboard a private yacht,Footnote 11 and some tour operators offer land-based “deep-field” activities, including, for example, mountain climbing expeditions and ski expeditions.Footnote 12

In the last three decades, the diversity of types of activities that tourists conduct in Antarctica has also increased significantly. This diversification stems from, for example, changing demands from tourists and from the strategy of tour operators to distinguish themselves from their competitors. Activities carried out in the AntarcticFootnote 13 include marathons,Footnote 14 mountain climbing, camping,Footnote 15 scuba diving, kayaking, cross country skiing, downhill skiing, long distance swimming, base jumping,Footnote 16 video-making with drones,Footnote 17 visits to penguin colonies by helicopter, heli-skiing from super yachts,Footnote 18 and stays in semi-permanent luxury camps in the Antarctic interior.Footnote 19 Individual tourists may also seek to experience in Antarctica activities that they have undertaken on other continents, to showcase their experiences on all continents. For instance, in the 2019–2020 season, an Indian national traveled to Antarctica with his motorbike because of his personal “seventh continent-dream”: “I had ridden across six continents and my dream for the last 25 years has been to ride on the seventh.”Footnote 20 Other manifestations of the growth of Antarctic tourism are the increase in the number of sites visited (now > 600) and the lengthening of the season.Footnote 21

This Article will analyze the efforts within the Antarctic Treaty System to address concerns about Antarctic environmental degradation from growing Antarctic tourism. These efforts have been sclerotic and inadequate, partly because of the strong consensus rule that operates within this regime, but there are ways to enhance the efficacy of this rule so as to meet the political will that exists among a sizable group of participating states to take conservation more seriously.

II. Regulatory Responses and Outstanding Policy Questions

A. Antarctic Governance

In 1959, the Antarctic TreatyFootnote 22 was signed by twelve countries involved in international scientific cooperation in the International Geophysical Year of 1957/58: seven states that have claimed territorial sovereignty over parts of Antarctica during the first half of the twentieth century (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, Norway, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom) and five other states that did not make claims (Belgium, Japan, the Soviet Union, now succeeded by Russia, South Africa, and the United States). Of these five non-claimant states, the United States and Russia maintain a “basis” for a territorial claim. Based on an agreement to disagree on the extant territorial claims in the area, these states agreed to govern Antarctica jointly. The Treaty entered into force in 1961 and, as of June 2023, has twenty-nine Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (Consultative Parties) that govern the Antarctic through consensus-based decision making: the twelve original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty and seventeen other contracting Parties, which—in accordance with Article IX(2) of the Antarctic Treaty—have received consultative status due to their continuing substantial scientific research efforts in the Antarctic Treaty area. There are also twenty-seven non-Consultative Parties to the Treaty.Footnote 23

Article IV of the Treaty continues to be pivotal for the seven claimant states and the previously five but now forty-nine other Contracting Parties that do not recognize any territorial claims. Article IV effectively shelved the territorial disputes over the Antarctic continent by providing that nothing contained in the Treaty shall prejudice their respective legal positions on the sovereignty issue and no acts or activities under the Treaty shall be considered as strengthening or denying such claims. Furthermore, no new claims or enlargement of such claims shall be asserted.Footnote 24 This unique legal setting distinguishes the Antarctic Treaty regime and its evolution from other multilateral treaty arrangements, including several multilateral environmental agreements and their Conference of the Parties.

The Consultative Parties meet annually at the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM), and since 1961, several other associated but separate international treaties in relation to Antarctica have been adopted. The most recent large international agreement adopted by the Consultative Parties is the Protocol and its six annexes.Footnote 25 With the Protocol—signed in 1991 and in force since 1998—Antarctica has been designated as a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science,Footnote 26 which also explains that the main aim of the Protocol is to establish comprehensive environmental protection in Antarctica.Footnote 27

Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty constitutes the basis for representatives of Consultative Parties to recommend “measures” to their governments. This resulted in the adoption of many so called “recommendations” at the ATCMs from 1961 to 1994. In 1995, “to increase the efficiency and clarity of the decision-making process,”Footnote 28 the recommendations were divided into three categories: measures, decisions, and resolutions.Footnote 29 A measure is a “text which contains provisions intended to be legally binding once it has been approved by all the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties,” which has to be approved “in accordance with paragraph 4 of Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty.”Footnote 30 A decision relates to “an internal organizational matter,” which “will be operative at adoption or at such other time as may be specified,” and a resolution is a “hortatory text,”Footnote 31 often on substantial issues but not intended to be legally binding.

The complex of the Antarctic Treaty, the associated separate international agreements, and the measures, resolutions, and decision under the Treaty and these agreements constitutes the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS).Footnote 32

B. ATCM Discussions on Antarctic Tourism and Concerns Expressed

Tourist activities fall under the scope of the Protocol. Consequently, the Parties to the Protocol (all twenty-nine Consultative Parties and thirteen other non-Consultative Parties) have to ensure that the tourist activities that fall under their jurisdiction take place in a manner consistent with the environmental principles of Article 3 of the Protocol and comply with requirements regarding prior environmental impact assessment (EIA)Footnote 33 and the more specific prohibitions and obligations of the Annexes to the Protocol. These prohibitions and obligations relate, for instance, to waste management, the protection of flora and fauna, and special protection of areas with outstanding values.

But while Antarctic tourism is evidently not “unregulated,” the Protocol's provisions are not specifically tailored to regulate tourism. Shortly after the adoption of the Protocol in 1991, five Consultative Parties (Chile, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain) submitted a proposal for a separate annex to the Protocol with rules on tourism and other non-governmental activities,Footnote 34 but no consensus could be reached on the need for such a separate annex. Antarctic tourism was still relatively limited at that time, and the Consultative Parties were mainly concerned with the ratification process of the Protocol. The strong self-regulatory efforts of IAATO have most likely also played a role in limiting support for additional regulatory action by the ATCM.Footnote 35

Since 2004, the year in which an Antarctic Treaty Meeting of Experts on tourism was organized by Norway, the discussion on tourism intensified. Since that year, Antarctic tourism has been the subject of extensive discussions at each ATCM on the basis of papers and proposals submitted by Consultative Parties and experts. Kees Bastmeijer and Neil Gilbert have summarized these discussions and explain that concerns expressed by Consultative Parties over the past twenty years relate to: (1) cumulative impacts for the Antarctic environment; (2) loss of pristine areas and related scientific and wilderness values; (3) potential interference with scientific research; (4) potential disruption to national programs if search and rescue is required; (5) human safety and search and rescue issues; and (6) increasing challenges in assessing and authorizing activities.Footnote 36

Many proposals from Consultative Parties for ATCM action related to relatively specific issues, which led to ATCM discussions with a strong ad hoc and piecemeal character. At the ATCM in 2009 the United Kingdom proposed therefore to adopt a “strategic vision” of Antarctic tourismFootnote 37 “to establish the broad principles by which the Antarctic Treaty Parties will manage tourism.”Footnote 38 Consensus on the proposed vision could not be reached, but the discussions resulted in the adoption of non-legally binding General Principles of Antarctic Tourism.Footnote 39 However, after this more fundamental debate in 2009, the ATCM discussions fell back to the piecemeal approach, depending on the issues raised in annually submitted ATCM papers.

In 2011–2012, an ATCM Intersessional Contact Group (ICG) made an inventory of eighteen “outstanding questions” relating to the growth and diversification of Antarctic tourism.Footnote 40 At ATCM 39 in 2016, “[t]he Meeting agreed that there was a need to be proactive and develop a forward pathway to address issues relating to tourism.”Footnote 41 A year later in 2017, the ATCM “reiterated its commitment to a strategic approach to tourism management,”Footnote 42 and in 2019, the ATCM again noted the urgency of discussing Antarctic tourism-related topics in light of “the significant growth projected for the tourism industry.”Footnote 43

In the intersessional period between ATCM 44 (2022) and ATCM 45 (2023), a small group of countries took the initiative “to jointly accelerate and support an ATCM-wide, transparent and inclusive debate and subsequent decision making on the future of Antarctic tourism.”Footnote 44 They organized a workshop in Paris from March 8–10, 2023, which resulted in several working papers with proposals for ATCM 45 in Helsinki. According to one of the working papers submitted by a group of countries, the workshop “led to a common belief that the concerns associated with the growth, diversification and compliance in relation to Antarctic tourism require the ATCM to take responsibility for governance action.”Footnote 45

C. Regulatory Responses of the ATCM Since the Adoption of the Protocol

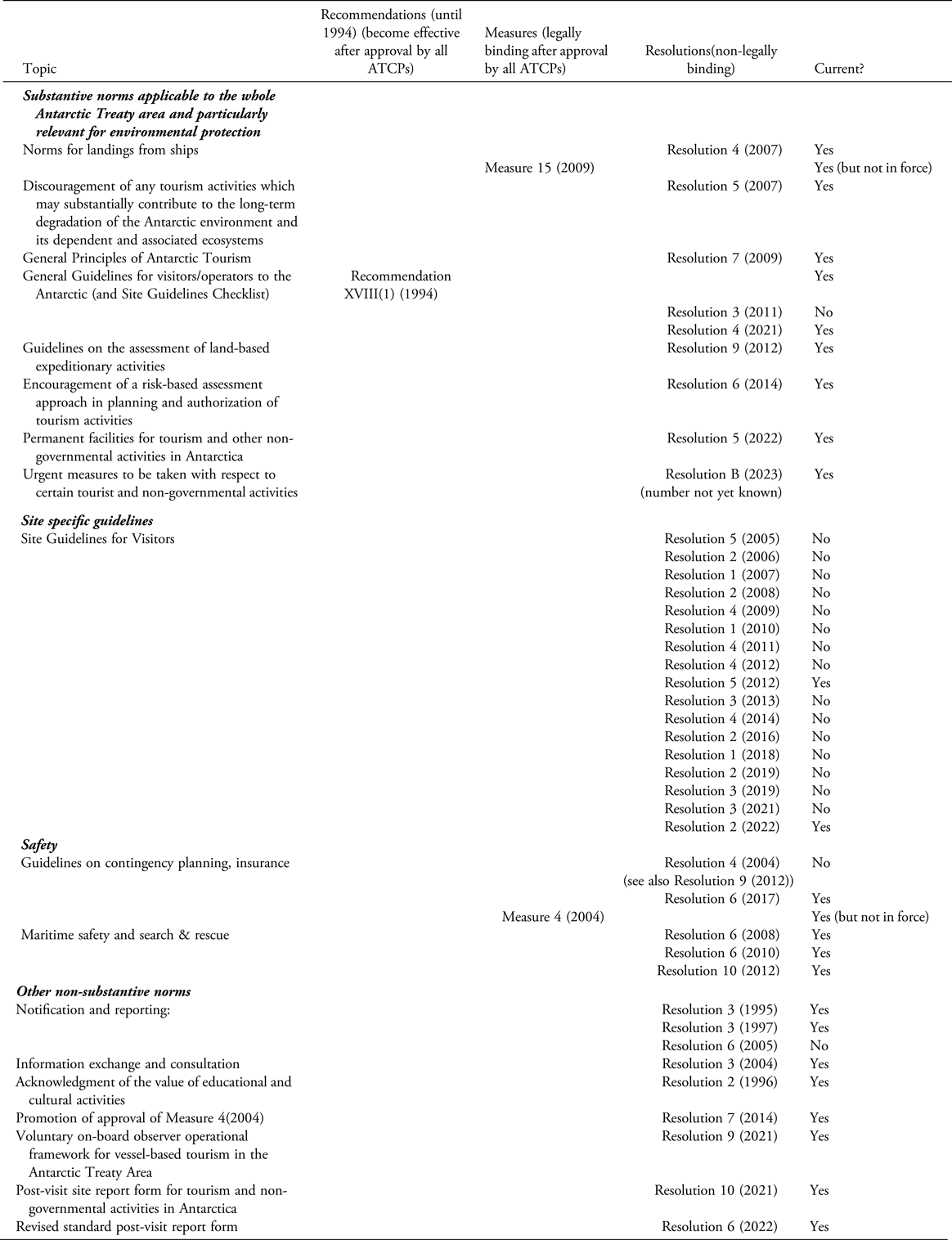

Since the adoption of the Protocol in 1991, the ATCM deliberations on Antarctic tourism have resulted in the adoption of one recommendation, two measuresFootnote 46 and forty resolutions (Table 1 and Figure 1). At first glance this looks impressive, however, the two measures that were adopted in 2004 and 2009 focus on fairly specific topics (safety and certain conditions for making tourism landings), and neither is yet in force because neither has been approved by all states that had consultative status at the time of adoption. Measure 4 (2004) is waiting for approval by eleven Consultative Parties, and the entry into force of Measure 15 (2009) still requires fifteen additional approvals.Footnote 47

Table 1. Recommendations, measures, and resolutions on Antarctic Tourism adopted since 1991, based on the Antarctic Treaty Database, available at https://www.ats.aq and Ferrada, infra note 62.

Figure 1. Tourism related recommendations, measures and resolutions, adopted since the signing of the Protocol (1991), per topic and status, based on the Antarctic Treaty Database, available at https://www.ats.aq and Ferrada, infra note 62. Recommendations (until 1994) and measures (since 1995) are legal norms that are in force or not in force, depending on whether they have been approved by all states that had consultative status at the time of adoption (Antarctic Treaty, supra note 3, Art. IX.4). Recommendations, measures, and resolutions may be current or not current, depending on whether it has been declared expired or replaced.

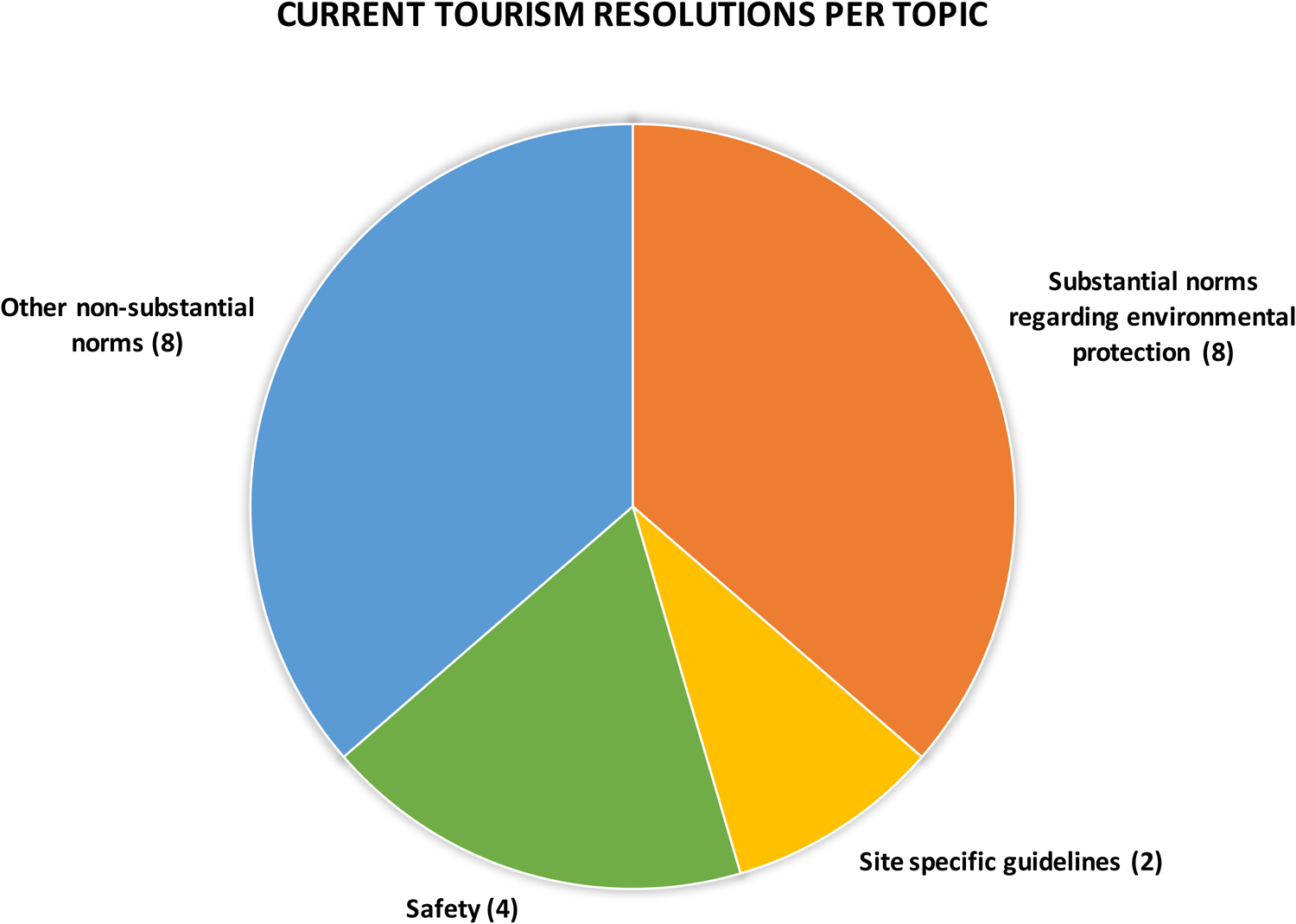

Furthermore, a closer analysis of the resolutions shows that only twenty-two of the forty tourism-related resolutions are still current (Figure 1).Footnote 48 The other eighteen resolutions are not current because they have been updated and replaced by later resolutions (fifteen of these eighteen relate to site specific guidelines).

The above quantitative aspects must of course be viewed in relation to the substance of the measures and resolutions adopted. Of the twenty-two current resolutions, only eight relate to substantive norms that apply to the entire Antarctic region and that are of particular relevance for environmental protection (Figure 2). Of these eight resolutions, most are characterized by relatively general terminology and do not establish clear normative restrictions for Antarctic tourism. This applies, for instance, to the above-mentioned General Principles of Antarctic Tourism of Resolution 7 (2009). The other fourteen current resolutions focus on guidelines for specific sites, safety issues, and non-substantive/procedural issues (Figure 2). As noted, all resolutions are—in accordance with Decision 1 (1995)—not legally binding under international law.

Figure 2. All current tourism resolutions adopted since the signing of the Protocol (1991).

D. Outstanding Policy Questions

The adopted measures and resolutions provide further guidance to Antarctic tourism, but most of the more substantive and strategic policy questions—including those identified in 2012—have still remained unanswered.

An important outstanding question is whether the ATCM should “adopt regulatory instruments to prevent or regulate the further expansion of tourist activities in Antarctica.”Footnote 49 For instance, should “more strategic regulatory instruments be considered, such as the concentration of tourism to certain areas, . . . maximizing numbers of visitors per Antarctic regions/per seasons/per site, etc?”Footnote 50 Or “[s]hould pristine areas be closed for any type of human visitation in the future . . . to preserve these areas as reference areas for future scientific research or because of the intrinsic values of these sites?”Footnote 51 A related unanswered question is “[h]ow . . . cumulative impacts by visitation (e.g., at popular tourist sites) [should] be measured and managed.”Footnote 52

Besides such questions, which particularly relate to the growth and expansion of Antarctic tourism, various other outstanding questions (of concern to some, but perhaps not all, Consultative Parties) relate to the diversification of tourism activities in Antarctica. “[S]hould Antarctica be open to all types of activities or should ‘priority . . . be given to tourism focusing on educational enrichment and respect for the environment’?”Footnote 53 “Are there any activities that are currently not being undertaken but may be initiated in the future and that would be considered unacceptable or inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty, the Protocol and the General Principles of Antarctic Tourism, and which could be prohibited in advance?”Footnote 54 Related to the previous question, “[s]hould the potentially increasing use by tourists of infrastructure, established with the principal aim of supporting scientific activities (e.g., air connections, bases, etc.), be considered as a concern, and if so, how should the ATCM respond to this concern?”Footnote 55

Another set of policy questions that have not received an answer from the ATCM relates to strengthening international cooperation and compliance. For instance, should an administrative fee on tourism operators be levied “to support environmental monitoring work”?Footnote 56 “Is there a need to enhance the level of cooperation between IAATO and the [Consultative Parties] for the purposes of consistency of assessment and strengthening compliance?”Footnote 57 For instance, “[a]re there any bylaws, guidelines or best practices of the tourism sector [IAATO] that require codification in a recommendation or measure of the ATCM?”Footnote 58 And “[w]hat could be done in order to allow [National Competent Authorities] to better monitor the actual implementation, in the field, of the activities they authorize, and better identify the unauthorized activities?”Footnote 59 For instance: “Should the ATCM develop a joint observation scheme?”Footnote 60 All these questions have been tabled at ATCMs and most of them have been the subject of comprehensive discussions, but no consensus could be reached on the right answer.

Such a large number of unanswered policy questions fuels the criticism of the ATCM's inability to take proactive decisions, especially in light of an increasing number of scientific publications with evidence that tourism has harmful environmental effects.Footnote 61 Indeed, in the social science and humanities literature, the ATCM has increasingly been criticized for its lack of decision making.Footnote 62 The lack of action by the ATCM in response to fast increasing tourism paints a stark picture of a treaty organization failing to respond adequately to pressing international environmental priorities.

III. The Difficulty of Reaching Consensus

A. The Consensus Rule in Antarctic Governance

The “consensus rule” refers to the general rule that decisions in the ATCM are adopted with the consent (in the sense of “absence of objection”)Footnote 63 of all Consultative Parties present at the meeting. The consensus rule was made explicit in Rule 23 of the 1961 Rules of Procedure and is formulated as follows in the current version of the Rules of Procedure:

Without prejudice to Rule 21, Measures, Decisions and Resolutions, as referred to in Decision 1 (1995), shall be adopted by the Representatives of all Consultative Parties present and will thereafter be subject to the provisions of Decision 1 (1995).Footnote 64

Marie Jacobsson has explained that the consensus rule was a precondition for the claimant states to accept the Antarctic Treaty: “Attempts to have a decision-making procedure by majority rule failed. The claimant states were not prepared to accept any decision-making procedure that would not have given them a veto. The consensus principle was a prerequisite.”Footnote 65 Tucker Scully has explained that the consensus rule “adds important political reinforcement to the juridical accommodation set forth in Article IV” because “[e]ach party is provided the assurance that it cannot be outvoted on decisions that could affect the issues of sovereignty dealt with in Article IV.”Footnote 66

Revisions of the Multi-Year Strategic Work Plan for the ATCM also require consensus.Footnote 67 In relation to procedural issues, there are some exceptions. For instance, adoption of the Final Report of the ATCM requires “a majority of the Representatives of Consultative Parties present.”Footnote 68 In practice the consensus rule is also applied for the adoption of the Final Report, which has always been successful until the 2022 ATCM in Berlin. For measures, consensus is needed for adoption and unanimous subsequent approval is required for entry into force: A measure does not become effective until formally approved by all Consultative Parties that were entitled to participate in the ATCM at which the measure was adopted.Footnote 69 There is an exception to this rule, where, unless the measure specifies otherwise, formal approval is not necessary and “tacit approval” is enough.Footnote 70

The consensus practice of the ATCM should be distinguished from the practice of “best efforts to reach consensus, before taking a decision by a majority.” The latter approach is taken at many of the United Nations convened conferences, the most famous being the United Nations Conference of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).Footnote 71 ATCM consensus decision making should also not be equated with “pseudo-consensus” practices as can be observed in some environmental treaty conferences, where, notwithstanding a formal objection by one or two participants, a “consensus” was declared by the chair.Footnote 72 At the ATCM, it is the substantive consensus that controls the conduct of business, in which the chairs of the plenary, its Working Groups as well as the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) under the Protocol, get sufficient assurance that the Consultative Parties present at the meetings are satisfied with the outcome of the negotiation. This requires attention for the interests of all Consultative Parties. Still, decision making is not based on unanimity because consent need not be expressed explicitly and the system continues to function on the basis of the absence of objections.

The fundamental character of the consensus rule and the substantial progress of Antarctic governance explain why the rule has been referred to as “the ATS principle of consensus” by some Consultative PartiesFootnote 73 and why it has so often been considered a cornerstone of Antarctic governance. For instance, in the time period of Protocol negotiations, the Under-Secretary of Foreign Affairs of Chile, Edmundo Vargas, stated:

If man[kind] has behaved maturely in this southernmost region it is because the wise mechanism of consensus has functioned. Perhaps we have not achieved all the things we would have liked to, but what we have done has been permanent.Footnote 74

B. Antarctic Tourism: The Difficulty of Reaching Consensus

That many of the concerns and important policy questions discussed above have not led to action by the ATCM is not because of a lack of proposals and discussions. Virtually all important tourism-related policy questions regarding growth, diversification, and enforcement have been the subject of concrete proposals for action.

For example, between 2004 and 2008, no consensus could be reached on concrete proposals to ban permanent facilities for tourism, such as hotels. In 2009, no consensus could be reached on a proposal for a vision on Antarctic tourism that had been worked out into many concrete components. In 2012, the ATCM could not agree on the priority policy questions proposed by an Intersessional Contact Group.Footnote 75 Also the discussions of recommendations of the CEP, based on a comprehensive tourism study,Footnote 76 did not result in agreed action, except for requesting the CEP to conduct more studies (e.g., on monitoring).Footnote 77

While at that 2012 ATCM “[t]here was a broad view that there were gaps in the current framework of regulation for land-based activities, in particular the expansion of tourism activities into the Antarctic interior,”Footnote 78 also on this issue no concrete decisions were taken. In 2013 the intersessional work on diversification of Antarctic tourism did not result in any concrete ATCM action. In 2016 “some Parties suggested the possibility of adopting a quota or some other form of system to regulate and limit tourism numbers,” however, “others felt this was not necessary.”Footnote 79 In 2017 no consensus was reached on a proposal to “advance the General Principles on Antarctic Tourism (2009) and make them practical and operational through six tracks of action.”Footnote 80 At that meeting, the Consultative Parties could also not reach consensus on action for establishing a “centralised depository of tourist sites and activities,”Footnote 81 and they could also not agree on the implementation of “a black-list of non-governmental actors” to prevent future unauthorized voyages to Antarctica.Footnote 82 Also discussions at the ATCM in 2019 on the establishment of a fee for tourists, for instance to finance monitoring, did not result in a concrete decision.Footnote 83

C. Possible Reasons for Absence of Consensus

Reasons for not reaching consensus vary per topic, time period, and Consultative Party. During discussions at the ATCM and in the ATCM Final Report, the record may not always reflect the true reasons for making objections and exploring these reasons and carefully assessing whether such reasons can be surmountable by further negotiations would be sine qua non for effective consensus-making efforts within the ATS. From observations during ATCMs and informal talks with ATCM delegates, the authors can suggest the following potential reasons.

Consultative Parties may be concerned that certain new measures would not fit into their existing domestic implementation legislation, for instance because the topic of such new measures (e.g., human safety) falls outside of the legal scope of that legislation (e.g., environmental protection). Some Consultative Parties may consider amendment of the domestic legislation too time-consuming.

Mutual relations between Consultative Parties and sovereignty issues may also play a role. For instance, a claimant state may consider limitations to certain new tourism developments in its claimed territory unacceptable, particularly if another claimant state is already conducting or authorizing such activities in the same region.

It is also conceivable that a Party does not want to limit certain potential future developments, for instance in light of scientific, economic, or other interests. Certain Parties may also consider tourism as a source of financing scientific research and infrastructural facilities.

Uncertainty or different views about how various Antarctic principles and values should be defined and what could be the threshold for determining unacceptable impacts can also lead to decisions not being taken. This appears to be particularly relevant with regard to Antarctica's intrinsic values (e.g., wilderness values), which are referred to in Article 3(1) of the Protocol and Annex V to the Protocol.Footnote 84

Another factor that seems to play a role in the difficulty of reaching consensus is the emphasis on science-based decision making in the CEP and ATCM and particularly the way this is interpreted by some states. Science-based decision making aims to ensure that decisions are based on available knowledge as much as possible, however, it does not necessarily exclude decision making in situations where gaps in knowledge exist. In such situations, decisions may be based on the best available knowledge as well as the precautionary approach. Consultative Parties appear to agree on the need to follow the best available science and precaution, but may disagree on what that means in given circumstances.

Another possible reason is that, in parallel with rising tensions in international relations and lack of cooperation within international organizations generally and as the number of Consultative Parties rises, the spirit of Antarctic cooperation has become less assured over time. Great power politics among strategic competitors, which were difficult enough in the context of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, have become even more complex given the rise of China and its intention to influence ATS proceedings.Footnote 85 As countries find it difficult to reach agreement on climate change, nuclear disarmament, and even the Ukraine conflict, these pressures may have an impact on the ability to cooperate.

Clearly articulating and understanding the true reasons of negative positions by one or more Consultative Parties regarding further regulation of Antarctic tourism is extremely important for overcoming the difficulty of reaching consensus. For example, potential conflict with domestic law may be prevented by listening to the concerns and investing time to find compromise legal language that provides sufficient flexibility.Footnote 86

IV. The Consequence of the Absence of Consensus: Decision Making by Non-decision making

While it has never been the aim to close Antarctica for human presence (facilitating science was the primary focus of the Treaty), the Consultative Parties granted Antarctica a protected status at an early stage. With the adoption of the 1964 Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora, Antarctica was designated as a “Special Conservation Area.”Footnote 87 The protected status of the whole of Antarctica was also reflected in Article 2 of the Protocol: “The Parties commit themselves to the comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystems and hereby designate Antarctica as a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.”Footnote 88 This aim is also reflected in opening addresses and interventions of representatives of certain Consultative Parties during the negotiations of the Protocol. For instance, in 1990, the Chilean foreign under-secretary stated that the ATCM is “faced with the challenge of reconciling a pollution-free Antarctica with one that is also open to human activity.”Footnote 89

To enhance the protection of the Antarctic environment, the Protocol could have stipulated that all types of non-scientific or all non-governmental activities are prohibited unless explicitly agreed by the Consultative Parties that the activities may be conducted in Antarctica. The Antarctic would in that case become a real natural reserve with only activities that all Consultative Parties consider appropriate. However, this is not the approach that was taken; the opposite is the case. Under the legal design of the Antarctic Treaty and Protocol, Antarctica is open to peaceful use by all states and their nationals, except for activities that are explicitly prohibited or that are contrary to the principles or purposes of the TreatyFootnote 90 or contrary to the Protocol.Footnote 91 Consequently, consensus is needed for any explicit prohibition or additional condition for the conduct of human activities in Antarctica.

Thus, for the comprehensive environmental protection of Antarctica beyond what is provided for in the Protocol, the consensus rule in reality presents a serious hurdle to overcome. This is particularly true for rapidly developing activities in Antarctica such as Antarctic tourism, because absence of consensus does not postpone such developments. In fact, lack of consensus results in “decision making by non-decision making”: because consensus to prohibit an activity is not reached, the activity is de facto allowed as long as the other provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and the Protocol are respected.Footnote 92 Procedures on EIA do not prevent this as international decision making on whether specific projects may proceed after the conduct of an EIA is missing. Even if—on the basis of a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation—it is concluded that a project will cause “more than [a] minor or transitory [impact]” on the Antarctic environment, the final decision is made by the country initiating or assessing the project.Footnote 93

Thus, it is evident that within the current framework the default is to allow tourist activities unless consensus is reached on prohibitions or limitation, while it is also clear that it has been very difficult to reach consensus on most of the outstanding policy issues surrounding Antarctic tourism. This has resulted in a very limited regulatory response to an issue that is becoming increasingly pressing. To promote the legitimacy of the ATCM, it is important to find ways to strengthen its decision making, notably in relation to Antarctic tourism.

V. Strengthening ATCM Decision Making

A. Consultative Parties Getting Impatient: Decision to Start Negotiations on a Comprehensive and Consistent Framework for the Regulation of Antarctic Tourism

It would be too simple to propose the removal of the consensus rule to strengthen decision making in the ATCM. Such a proposal would ignore the history and central role of consensus in Antarctic governance and would be politically unacceptable to many Consultative Parties. It would also raise questions on the conformity with Article IV of the Antarctic Treaty and overlook the positive aspects of the rule, such as commitment of all Consultative Parties to implement joint solutions. The Antarctic Treaty System is built on the premise that any substantive decision that directly relates to the management of Antarctica requires at least a tacit consent of each of the Consultative Parties.

Nonetheless, the foregoing discussion also makes clear that reaching consensus on many tourism-related issues has long been problematic, while Antarctic tourism is increasing continuously and substantially. This makes at least a number of Consultative Parties increasingly impatient in light of the above-discussed concerns and the phenomenon of decision making by non-decision making. For ATCM 45 in Helsinki (May 29–June 8, 2023), twelve Consultative PartiesFootnote 94 tabled a working paper in which they state that “policy decisions are being postponed while the tourism market and activities develop rapidly.”Footnote 95 According to these parties “a point has been reached where guiding and robust policy choices have to be made that cannot be expected from the industry.”Footnote 96 Therefore they proposed to ATCM 45 to decide to convene a series of Special ATCMs “with the aim of developing a comprehensive and consistent framework for the regulation of tourism and other non-governmental activities in Antarctica.”Footnote 97 In the working paper they also identified topics as potential building blocks of such a framework: managing growth, managing diversification, monitoring, compliance and enforcement, safety and self-sufficiency (including search and rescue), and overall governance.

Based on this proposal and discussions in Helsinki, ATCM 45 adopted a Decision “to start a dedicated process to develop a comprehensive and consistent framework for the regulation of tourism and other non-governmental activities in Antarctica.”Footnote 98 For this purpose, a Special Working Group was established, which—according to the Decision—will have its first meeting of two days during ATCM 46 in India (May 2024). Because the content and scope of the framework are not yet clear, the legal status of the framework will have to be determined at a later stage.

The approach of developing a comprehensive framework can have several important advantages. For example, negotiating several tourism-related topics as a coherent package creates room for compromise and trade-offs. Such a comprehensive package can also create greater political will to get actively involved in the negotiations. However, it does not provide a guarantee of reaching consensus.

Below, a number of possible approaches and techniques to strengthen ATCM decision making are identified. These are important for increasing the chance of adoption of any regulation regarding Antarctic tourism, including the above-mentioned comprehensive framework. Some of these options would require a revision of the ATCM's Rules of Procedure, while others relate to improving the practice within the current system and Rules of Procedure, however, all options respect the fundamental character of the consensus rule in Antarctic governance.

B. Options for Strengthening Decision Making

1. Enhanced Deployment of Tools to Strengthen “Consensus Making” as Component of the Duty to Cooperate in Good Faith

During discussions at the ATCM in Berlin in 2022, one of the heads of delegation stated that consensus making is a “verb” and therefore requires “action” of Consultative Parties. Consensus is not something that simply is or is not there; it is the result of a process of consensus making. This is in line with research on the functioning of consensus decision making in other legal systems. For instance, based on an analysis of the functioning of consensus in different multilateral conferences, Suren Movsisyan concludes that consensus “can be reached only through negotiations.”Footnote 99 In this context he adopts the broad definition of negotiations by Kaufmann: “the sum total of all talks and contacts intended to work in a cohesive spirit towards one or more objectives of the conference . . . to solve disputes or conflicts existing prior to the conference, or arising during the session.”Footnote 100 As the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its North Sea Continental Shelf cases declared, such negotiations in good faith must be “meaningful, which will not be the case when either of them insists upon its own position without contemplating any modification of it.”Footnote 101

The consensus rule within a legal regime established by a treaty must also be implemented within an emerging international law of positive cooperation among the regime members, as pronounced by the ICJ.Footnote 102 The ICJ in the Whaling in the Antarctic case implicated the regime members’ duty to cooperate even within majority-controlled organs such as the International Whaling Commission,Footnote 103 and, a fortiori, within an ATCM that operates under strict consensus rule, all Consultative Parties have the duty to cooperate in good faith to achieve such consensus promoting the common objectives agreed to by all the Treaty and Protocol parties. This obligation also includes the duty to give due regard to the recommendations of the regime's scientific bodies, such as the CEP.Footnote 104

Based on the above acknowledgement, various initiatives could be taken to strengthen or support the process of consensus making.

One way to do so is increasing the efforts by Parties to cooperate in the intersessional periods between meetings to prepare proposals and informally discuss the sensitive components, for instance through the organization of an Antarctic Treaty Meeting of Experts, informal international workshops, formal or informal Intersessional Contact Groups, or bilateral meetings. Often these intersessional and informal discussions are of great importance to exchange knowledge on policy issues, to understand the positions of Parties, to establish good will, and to find solutions.

2. Exceptions to the Consensus Rule in Specifically Defined Situations

As briefly mentioned above, there are exceptions to the consensus rule, such as the adoption of the Final Report of the ATCM that only requires a majority.Footnote 105 It has been the practice to adopt the Final Report by consensus. The only exception so far was in 2022, when Russia objected to the inclusion of some paragraphs in the Final Report, which summarized statements and Plenary discussions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 106

One question is whether the effectiveness of the ATCM could be increased by allowing more exceptions to the consensus rule. Any debate focused on when and how such exceptions could be applied should be based on a comprehensive analysis of situations in which it would not be absolutely necessary for Consultative Parties to have an option to block consensus. It could be conceived that certain topics are less sensitive and, for example, have no or only very limited relevance from the perspective of Article IV of the Treaty, or other central interests of Consultative Parties, and for which deviation from consensus is considered acceptable. The precedents from other environmental regimes applying majority decision making for technical, scientific, and “derivative” regulationsFootnote 107 would be worth looking into, especially when designing a regulatory framework for Antarctic tourism. It is also conceivable that a distinction is made on the basis of the legal status of a decision. The consensus rule now applies to measures, resolutions, and decisions and the question is whether letting go of consensus for adopting resolutions would be negotiable. Such a revision to the ATCM Rules of Procedure would not implicate any question of amendment to Article IX of the Treaty.

If there is space for additional exceptions to the consensus rule, various options might be debated. In addition to decision making by simple or qualified majority, the Parties could add an “all-but-one” option. With this option one stays as close as possible to consensus, but the risk that one Consultative Party blocks (or continues to block) progress in the system is at least formally removed. Such an option might be paired with a concrete list of topics where this option would be available and with the assurance that Article IX(4) on the conditions for “the measures” to become effective would not be prejudiced.

Although possibly very controversial in the context of the Antarctic Treaty, an invocation of suspension of voting rights in the ATCM of a particular Party in event of egregious behavior is also legally plausible. It is legally allowed under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties in case of a material breach by that Party of a multilateral treaty with a unanimous agreement of the Parties excluding the breaching state.Footnote 108

3. Improving the Functioning of the Committee for Environmental Protection

The CEP has been established under the Protocol and is an advisory body to the ATCM.Footnote 109 The CEP meets in conjunction with the ATCM and has provided much valuable advice and guidance on the implementation of the Protocol.Footnote 110 Examples include the adoption of guidelines for the implementation of environmental impact assessment provisionsFootnote 111 and the development and revisions of international management plans for Antarctic Specially Protected Areas.Footnote 112 Such guidance and advice are adopted on the basis of consensus among the CEP members, which are the representatives of the Parties to the Protocol.Footnote 113

Also in the CEP, consensus is sometimes difficult to reach. An example relevant for the tourism debate is the lack of consensus in 2018 on the proposal to codify IAATO's bylaw to prohibit the use of remotely piloted aircraft systems (e.g., drones) for recreational purposes in wildlife-rich coastal areas.Footnote 114 More recently, this concern of not reaching consensus on CEP advice received explicit attention at the ATCM in response to a range of objections by China to CEP-proposals, such as the proposal to advise the ATCM to list the Emperor Penguin as Specially Protected Species under Annex II of the Protocol.Footnote 115 The 2022 Final Report of the ATCM states in relation to the CEP: “Recalling the actions taken by one Member at CEP XXIII to undermine consensus, most Parties expressed frustration that similar actions had been taken again at CEP XXIV.”Footnote 116

It is clear that these difficulties directly influence tourism-related decision making by the ATCM, especially with regard to issues on which the ATCM considers CEP advice important. When the consensus rule in the CEP leads to a lack of advice to the ATCM and the lack of advice leads to the suspension of decisions by the ATCM, a “double consensus hurdle” for decision making exists in practice.

As the discussions on the 2022 Emperor Penguin proposal in the CEP have shown, fundamental questions arise on how to apply science-based decision making (or providing advice to support such decision making) while taking due account of the need to act in a precautionary manner. In relation to the Emperor Penguin proposal, the CEP has “emphasised the importance of drawing on best available science to support CEP management decisions”Footnote 117 and with the exception of China “[m]embers also emphasised that the need for further research should not undermine the importance of taking a precautionary approach to environmental protection.”Footnote 118

These discussions may constitute an encouragement for the CEP not to wait for full scientific proof before formulating advice to the ATCM. They make it also important to acknowledge that—while decision making in the CEP is based on consensus—ATCM access to knowledge and advice should not entirely depend on consensus in the CEP. In fact, the Rules of Procedure ensure that the CEP report reflects all views, also if consensus could not be reached: “Where consensus cannot be achieved the Committee shall set out in its report all views advanced on the matter in question.”Footnote 119 It seems that the CEP is sometimes too focused on consensus and too reluctant to express, for instance, views of the majority (or “all members but one”) in its report to the ATCM, although it should also be recognized that if the failure to reach consensus in the CEP is politically motivated, the chance of reaching consensus within the ATCM will be small.

4. Enhancing Involvement of High-Level Officials or Politicians (e.g., “Ministerial on Ice”)

Ministerial or senior-level meetings are very rare in the Antarctic Treaty System. When in the 1990s progress in the discussions on the liability annex to the Protocol and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing was lacking, New Zealand took the initiative to organize the first ministerial meeting since the adoption of the Treaty. This meeting took place from January 24–28, 1999, including a stay in Antarctica at Scott Base (New Zealand) and McMurdo Station (United States) from January 25–28, 1999. In a press release, New Zealand Associate Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Simon Upton stated:

The business has always been handled by officials. That has worked well up to now. But with new pressures on the Treaty and increasing scientific and tourist traffic to the continent, officials are going to need political direction and encouragement if the Treaty System is to cope with the twenty-first century's demands.Footnote 120

He also stated that “he hoped the ice visit would provide some political momentum to the work of officials at future annual Consultative Meetings of Treaty Parties.”Footnote 121

It may be that consultations at higher political levels, as occurred in 1999, can lead to progress in decision making at ATCMs. The above discussions show that the officials have been unable to reach a decision on many tourism issues over the last three decades. Experiences in other environmental diplomacy settings show that high-level meetings do not necessarily result in progress, but gatherings such as the 1999 Antarctic ministerial meeting may create a useful stimulus for action.

5. Intensified Collaboration Among Consultative Parties as an Alternative or Possible First Step Toward ATCM Decision Making

Progress in the system does not always require formal decision making by the ATCM. For example, some of the countries can take joint initiatives, leaving others the option to join later. Such initiatives can then also constitute a solid basis for formal decision making by the ATCM when the time is right. For example, in the ATCM agreement on the establishment of an international observation system for tourism activities could not be reached, however, a group of Parties could decide not to wait for full ATCM consensus and start to implement such a joint observer scheme in respect of the tourist activities under their jurisdiction. Another example relates to the discussion on diversification of tourism. Agreement on whether Antarctica should be accessible to all types of tourism activities is difficult to achieve, but a group of countries may be able to achieve harmonization at the level of developing national policies and/or assessing permit applications.

Groups of Consultative Parties could also use the Final Report of the ATCM to be explicit about their common view on a particular policy issue. The “views and practices” reflected in the Final Reports may not by themselves be “decisions” of the Consultative Parties at the moment of adopting the Final Reports, but the accumulations of those views and practices may over time establish a basis for new initiatives to reach consensus. There are interesting precedents in other environmental regimes, forging the subsequent, perhaps grudging, agreement from a few recalcitrant parties through majority opinions repeatedly and consistently expressed in non-binding resolutions and report languages.Footnote 122

VI. Conclusions

The above discussions highlight the central place of the consensus rule in Antarctic governance, but also indicate that this rule raises challenges to ensuring timely and adequate international responses to important governance challenges deriving from growing Antarctic tourism. Despite the significant increase of Antarctic tourism, the serious concerns expressed by Consultative Parties, an increasing number of scientific publications on the impacts of tourism on the Antarctic environment, and the comprehensive discussions of the ATCMs on the basis of a large number of working papers and proposals, many strategic policy questions remain unanswered.

The ATCM's lack of ability to reach conclusions on key tourism issues is concerning from the perspective of the Protocol's aim to ensure comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment. This is particularly so because the lack of consensus does not simply result in postponing decision making. As explained in Section II, “open use” within existing frameworks is the basic principle on which the Antarctic Treaty has been built, and “non-use” is the exception and therefore requires consensus. Consequently, a lack of consensus results in “decision making by non-decision making”: because consensus to prohibit or restrict an activity is not reached, the activity is de facto allowed as long as the other provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and Protocol are respected.Footnote 123 For rapidly expanding activities such as Antarctic tourism, this means that the ATCM is unable to address them in a timely manner. As a consequence, the ATCM often finds itself in a position where developments can only be adjusted slightly, for instance through the adoption of voluntary guidelines on “how” to undertake the activities.

Setting aside the question of what substantive changes in tourism or environmental regulations might be needed from a policy perspective in the near term, it is clear that decision making within the ATCM has become slow and cumbersome, with Consultative Parties finding it difficult to make progress even where there is wide support for action. This has implications for the long-term health of Antarctic governance and its effectiveness. Too little progress with regard to the third pillar of the ATS—comprehensive environmental protection—may increase criticism from outside the system as well as within the system. As explained by Oscar Pinochet thirty years ago: “Treaties are not only violated by open and outright rejection. They can also be subject to the gradual abandoning of principles or to a lack of confidence in their real possibilities of action.”Footnote 124

In light of the above, there are good reasons for the ATCM to strengthen its decision making. Options discussed in this Article go from considering ways to make the consensus rule more flexible to intensified collaboration among Party states. Given the continuing, and in some cases increasing, environmental and political pressures facing Antarctica, it will be important for the Consultative Parties to give greater attention to how the ATCM can improve its ability to act and provide the kinds of leadership and regulation needed for the coming decades.