Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 September 2021

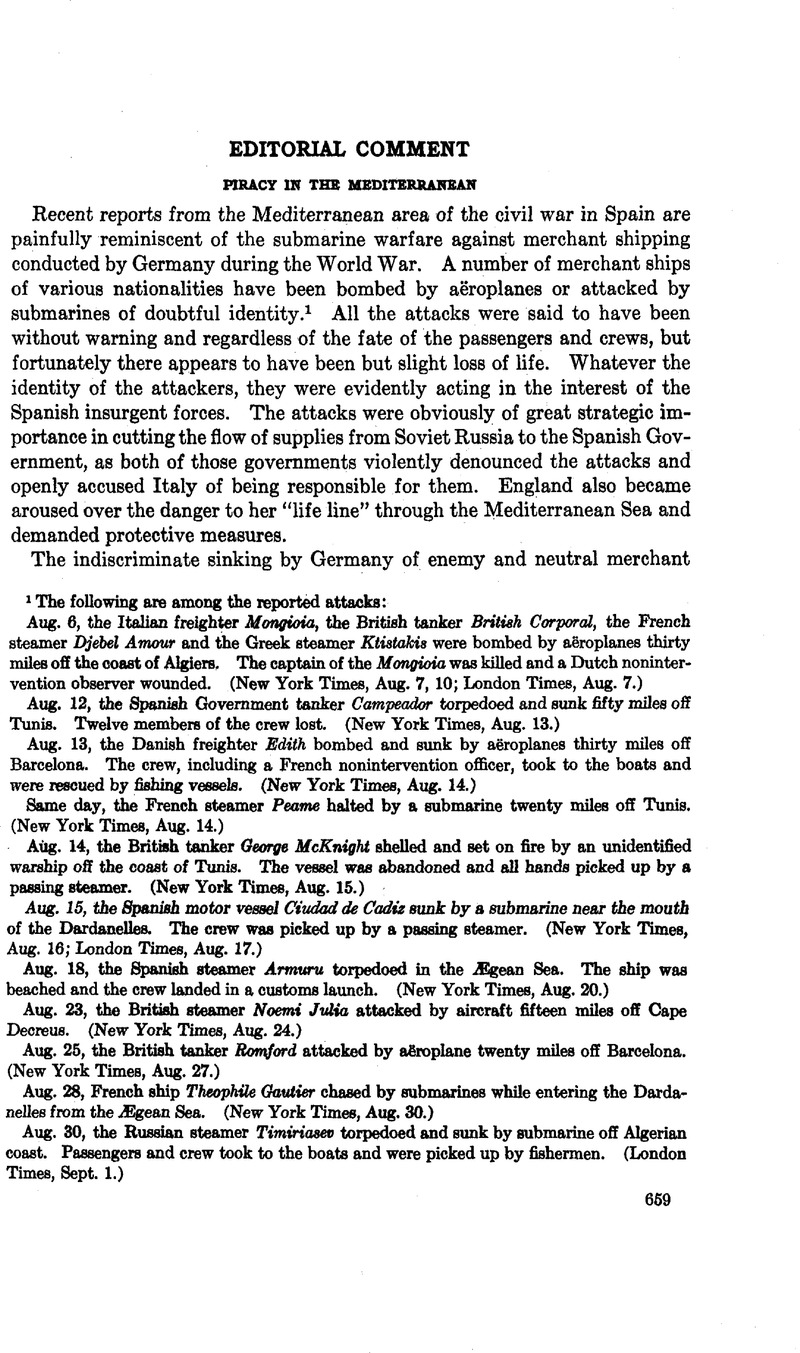

1 The following are among the reported attacks: Aug. 6, the Italian freighter Mongioia, the British tanker British Corporal, the French steamer Djebel Amour and the Greek steamer Ktistakis were bombed by aeroplanes thirty miles off the coast of Algiers, The captain of the Mongioia was killed and a Dutch nonintervention observer wounded. (New York Times, Aug. 7, 10; London Times, Aug. 7.) Aug. 12, the Spanish Government tanker Campeador torpedoed and sunk fifty miles off Tunis. Twelve members of the crew lost. (New York Times, Aug. 13.) Aug. 13, the Danish freighter Edith bombed and sunk by aeroplanes thirty miles off Barcelona. The crew, including a French nonintervention officer, took to the boats and were rescued by fishing vessels. (New York Times, Aug. 14.) Same day, the French steamer Peame halted by a submarine twenty miles off Tunis. (New York Times, Aug. 14.) Aug. 14, the British tanker George McKnight shelled and set on fire by an unidentified warship off the coast of Tunis. The vessel was abandoned and all hands picked up by a passing steamer. (New York Times, Aug. 15.) Aug. 15, the Spanish motor vessel Ciudad de Cadiz sank by a submarine near the month of the Dardanelles. The crew was picked up by a passing steamer. (New York Times, Aug. 16; London Times, Aug. 17.) Aug. 18, the Spanish steamer Armuru torpedoed in the JSgean Sea. The ship was beached and the crew landed in a customs launch. (New York Times, Aug. 20.) Aug. 23, the British steamer Noemi Julia attacked by aircraft fifteen miles off Cape Decreus. (New York Times, Aug. 24.) Aug. 25, the British tanker Romford attacked by aeroplane twenty miles off Barcelona. (New York Times, Aug. 27.) Aug. 28, French ship TheophUe Gavtier chased by submarines while entering the Dardanelles from the jEgean Sea. (New York Times, Aug. 30.) Aug. 30, the Russian steamer Timiriasev torpedoed and sunk by submarine off Algerian coast. Passengers and crew took to the boats and were picked up by fishermen. (London Times, Sept. 1.)

2 This statement is made with knowledge of the views of those who would attribute other motives to President Wilson and his advisers.

3 See Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, by Ray, Stannard Baker, Vol. I, pp. 382–383, Vol. II, p. 319Google Scholar.

4 For the text of the treaty see this JOTTBNAL, Supp., Vol. 16 (1922), p. 57.

5 For the text of the London Naval Treaty see this JOURNAL, Supp., Vol. 25 (1931), p.63. Part IV is on p. 78.

6 The Protocol of London of Nov. 6, 1936, is printed in this JOURNAL, Supp., Vol. 31 (1937), p. 137.

7 The text of the accord was published in the New York Times, Sept. 15, p. 16, and appears in this JOOTNAL, Supp., p. 179.

8 The text of the supplementary agreement appears in this JOURNAL, Supp., p. 182.

9 For definitions of the offense of piracy and a statement of the rights of persons accused of the crime, see the Draft Convention on Piracy, with comment, prepared by the Harvard Research in International Law and reproduced in this JOURNAL, Supp., Vol. 22 (1932), p. 741. An appendix contains a collection of the texts of piracy laws in various countries.

10 See the documents in the case of the British auxiliary cruiser Baralong published in British Parliamentary Papers, Misc. No. 1 (1916) [Cd. 8144], and reprinted in this JOURNAL, Supp., Vol. 10 (1916), pp. 79–86.

11 Cases on International Law (1922), p. 548, n. 6.

12 Oppenheim, International Law (2d ed.), Vol. I, pp. 341–342.

13 For the foregoing facts in the case of the Huasear, see Oppenheim, op. eit., and Moore, International Law Digest, Vol. II, pp. 1086–1087. This section of Moore's Digest gives other incidents in which similar questions were involved.