Article contents

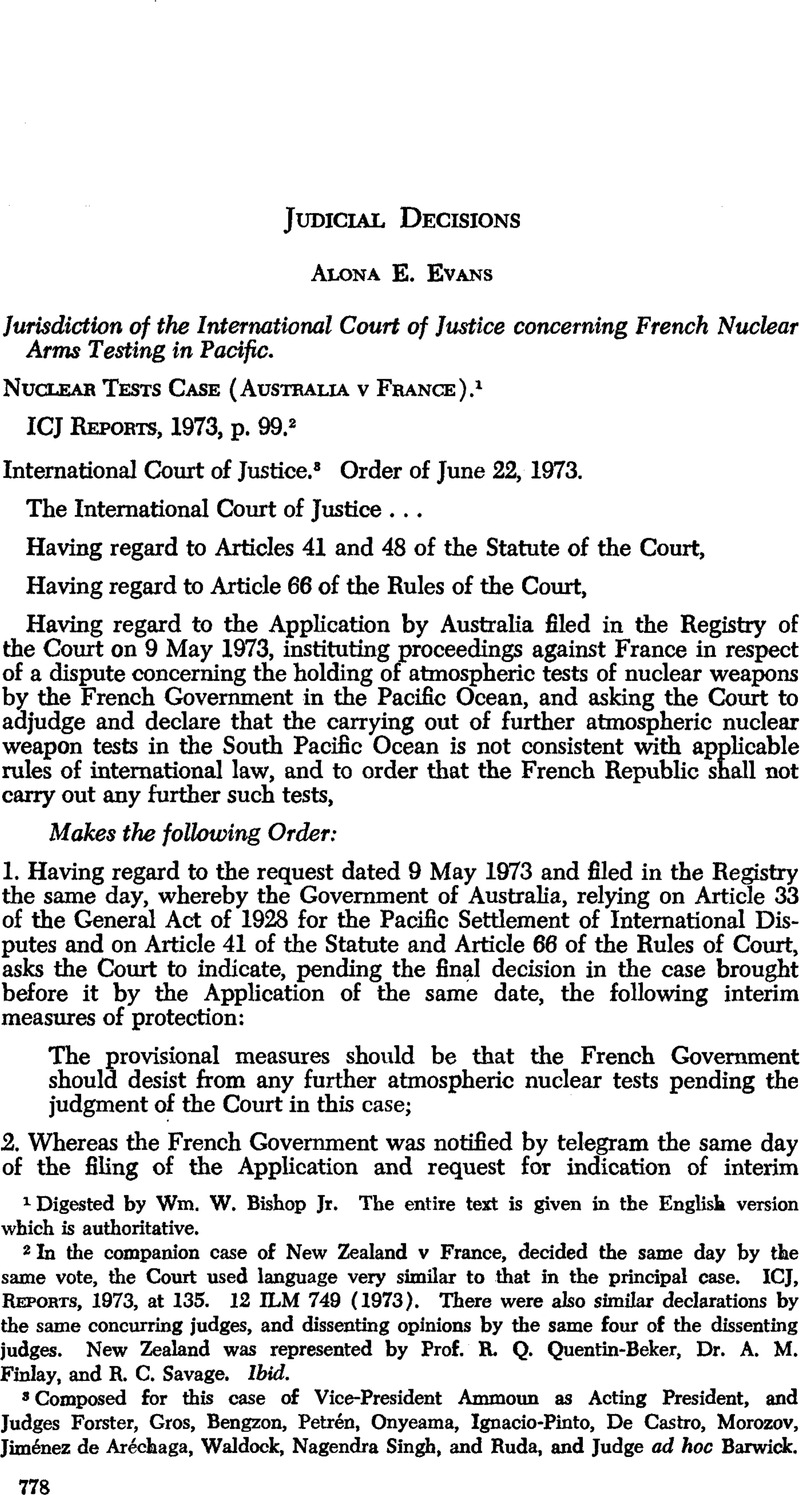

Nuclear Tests Case (Australia v France). ICJ Reports, 1973, p. 99

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1973

References

1 Digested by Wm. W. Bishop Jr. The entire text is given in the English version which is authoritative.

2 In the companion case of New Zealand v France, decided the same day by the same vote, the Court used language very similar to that in the principal case. ICJ, Reports, 1973, at 135. 12 ILM 749 (1973). There were also similar declarations by the same concurring judges, and dissenting opinions by the same fourof the dissenting judges. New Zealand was represented by Prof. R. Q. Quentin-Beker, Dr. A. M. Finlay, and R. C. Savage. Ibid.

1 Digested by Wm. W. Bishop Jr. The entire text is given in the English version which is authoritative.

2 In the companion case of New Zealand v France, decided the same day by the same vote, the Court used language very similar to that in the principal case. ICJ, Reports, 1973, at 135. 12 ILM 749 (1973). There were also similar declarations by the same concurring judges, and dissenting opinions by the same four of the dissenting judges. New Zealand was represented by Prof. R. Q. Quentin-Beker, Dr. A. M. Finlay, and R. C. Savage. Ibid.

3 Composed for this case of Vice-President Ammoun as Acting President, and Judges Forster, Gros, Bengzon, Petrén, Onyeama, Ignacio-Pinto, De Castro, Morozov, Jiménez de Aréchaga, Waldock, Nagendra Singh, and Ruda, and Judge ad hoc Barwick.

4 Although they concurred in the Order, Judges Jiménez de Aréchaga, Waldock, and Nagendra Singh, and Judge ad hoc Barwick made brief declarations.

5 Judge Forster, Gross, Petren, and Ignacio-Pinto gave dissenting opinions. It is not indicated which other judges voted against the Order of the Court.

Judge Forster thought the Court should have examined the question of jurisdiction more thoroughly before ordering provisional measures, particularly the question of the continuing validity of the General Act of 1928, since the French reservation (of matters relating to defense) in its Declaration of May 16, 1966 was so clear.

Judge Gros refrained from discussing the question of jurisdiction at any length, since the Court had deferred this until the next phase of the proceedings. He thought the decision of the Court on provisional measures was an improper application of Articles 41 and 53 of the Statute. He said in part:

A State does not have to wait two years or more for the Court to vindicate its claim that no justiciable dispute exists, for if that is the case there is nothing to be argued over; the other State, which has submitted the claim whose reality is contested, evidently has an equal right to have the Court acknowledge the existence of the dispute it invokes. But the equality between these claims is upset if, by the indirect means of the allegedly urgent ncessity for the indication of provisional measures, a presumption operates in favour of the applicant without the Court’s carrying out of any serious appraisal of the objection. . . .

[I]f in reality an indication of provisional measures prejudges the jurisdiction or the existence of jus standi, the Court does not have the power to grant these measures, because the condition laid down by Article 41 of the Statute will not have been respected. These conditions not having been fulfilled in the present case, the application of Article 41 in the Order or 22 June 1973 indicating provisional measures constitutes an action ultra vires.

Judge Ignacio-Pinto observed, inter alia, that:

Of course, Australia can Invoke its sovereignty over its territory and its right to prevent pollution caused by another State. But when the French Government also claims to exercise its right of territorial sovereignty, by proceeding to carry out tests in its territory, is it possible legally to deprive it of that right, on account of the mere expression of the will of Australia?

In my opinion, international law is now, and will be for some time to come, a law in process of formation, and one which contains only a concept of responsibility after the fact, unlike municipal law, in which the possible range of responsibility can be determined with precision a priori. Whatever those who hold the opposte view may think, each State is free to act as it thinks fit within the limits of its sovereignty, and in the event of genuine damage or injury, if the said damage is clearly established, it owes reparation to the State having suffered that damage.

- 3

- Cited by