No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

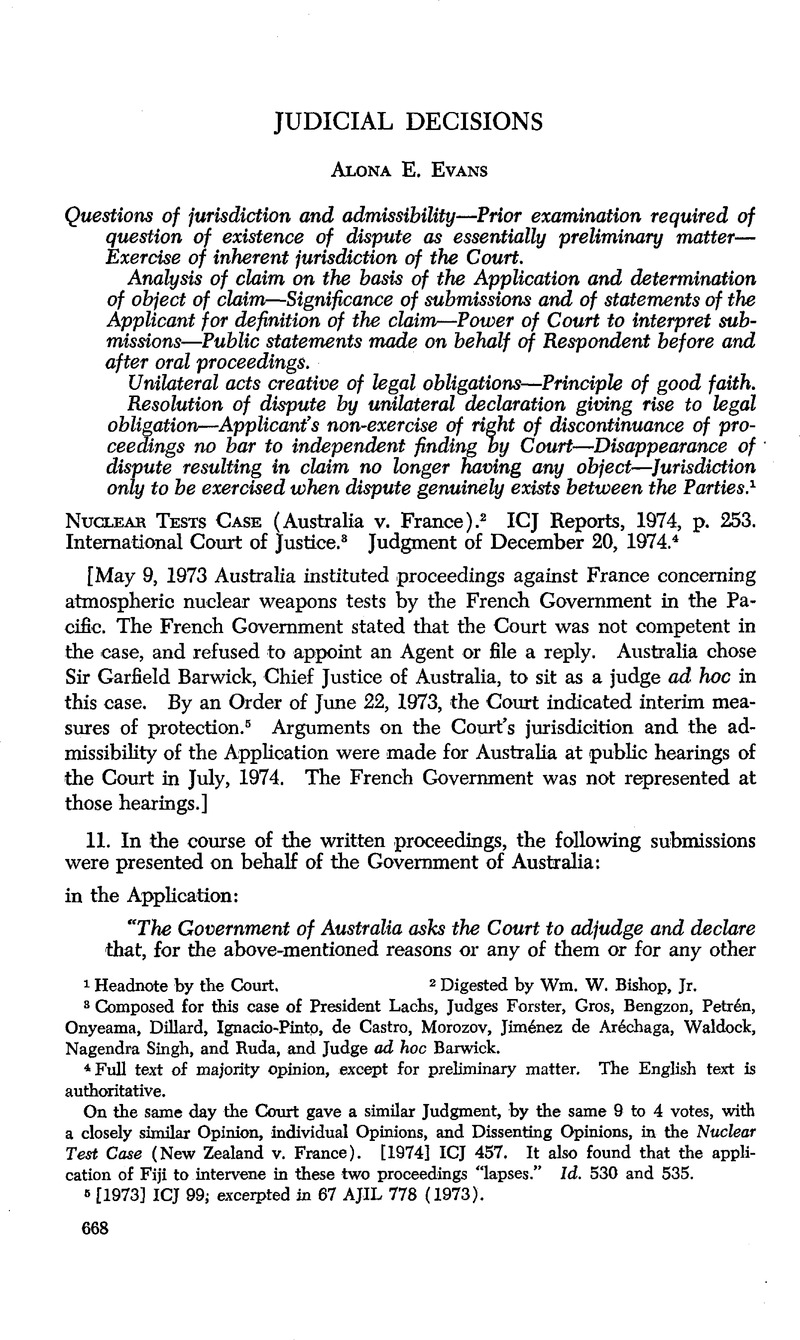

Nuclear Tests Case (Astralia v. France)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1975

References

1 Headnote by the Court.

2 Digested by Wm. W. Bishop, Jr.

3 Composed for this case of President Lachs, Judges Forster, Gros, Bengzon, Petrén, Onyeama, Dillard, Ignacio-Pinto, de Castro, Morozov, Jiménez de Aréchaga, Waldock, Nagendra Singh, and Ruda, and Judge ad hoc Barwick.

4 Full text of majority opinion, except for preliminary matter. The English text is authoritative.

On the same day the Court gave a similar Judgment, by the same 9 to 4 votes, with a closely similar Opinion, individual Opinions, and Dissenting Opinions, in the Nuclear Test Case (New Zealand v. France). [1974] ICJ 457. It also found that the application of Fiji to intervene in these two proceedings “lapses.” Id. 530 and 535.

5 [1973] ICJ 99; excerpted in 67 AJIL 778 (1973).

6 Referring to earlier approval and participation by Australia in atmospheric nuclear testing by the United Kingdom and the United States, Judge Gros said: “The Applicant has disqualified itself by its conduct and may not submit a claim based on a double standard of conduct and of law. What was good for Australia along with the United Kingdom and the United States cannot be unlawful for other States.”

7 Judge Petrén found the admissibility of Australia’s Application dependent “on the existence of a rule of customary international law which prohibits States from carrying out atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons giving rise to radio-active fall-out on the territory of other States.” He found no such rule. He added:

If a State which does not possess nuclear arms refrains from carrying out the atmospheric tests which would enable it to acquire them and if that abstention is motivated not by political or economic considerations but by a conviction that such tests are prohibited by customary international law, the attitude of that State would constitute an element in the formation of such a custom. But where can one find proof that a sufficient number of States, economically and technically capable of manufacturing nuclear weapons, refrain from carrying out atmospheric nuclear tests because they consider that customary international law forbids them to do so? The example recently given by China when it exploded a very powerful bomb in the atmosphere is sufficient to demolish the contention that there exists at present a rule of customary international law prohibiting atmospheric nuclear tests. . . . .

. . . . . The resolutions passed in the General Assembly of the United Nations cannot be regarded as equivalent to legal protests made by one State to another and concerning concrete instances. They indicate the existence of a strong current of opinion in favour of proscribing atmospheric nuclear tests. That is a political task or the highest urgency, but it is one which remains to be accomplished.