Article contents

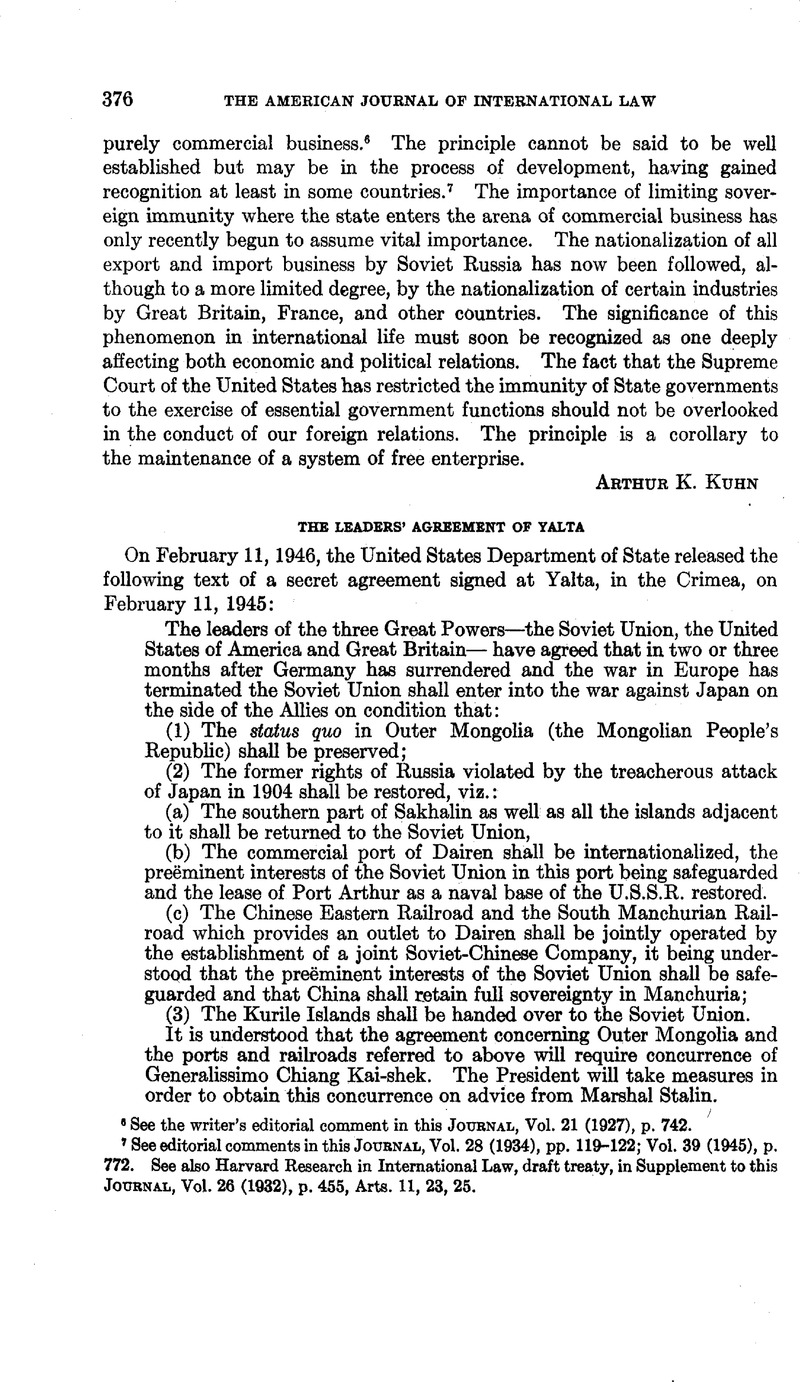

The Leaders’ Agreement of Yalta

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Editorial Comment

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1946

References

1 Department of Stale Bulletin, Vol. XIV, No. 347 (Feb. 24, 1946), p. 282.

2 The passage setting forth the agreed date for Soviet entry into the war against Japan— “ in two or three months after Germany has surrendered and the war in Europe has terminated”— apparently does not refer to termination of war in a technical sense.

3 See Louis Nemzer, , “The Status of Outer Mongolia in International Law,” this Journal, Vol. 33 (1939), pp. 452–464 Google Scholar.

4 The first paragraph of Article V of the Chinese-Soviet Agreement on General Principles signed at Peking on May 31, 1924, reads as follows: “The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics recognises that Outer Mongolia is an integral part of the Republic of China and respects China’s sovereignty therein;” League of Nations Treaty. Series, Vol. XXXVII, pp. 176, 178. Nemzer, writing in 1939, stated that, although Soviet Russia has acted upon the assumption that China’s jurisdictional authority in Outer Mongolia had varied in recent years, the Soviet Government “has never denied the sovereignty of China in this area;” Nemzer, as cited, p. 458.

5 Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XIV, No. 345 (Feb. 10, 1946), pp. 204–5.

6 By the terms of the Russian-Chinese Convention of March 27, 1898, for the lease of the Liaotung Peninsula to Russia, the lease was to run twenty-five years, and would have expired on March 28, 1923, unless prolonged by mutual consent. See MacMurray, J. V. A., Treaties and Agreements with and Concerning China, 1894–1919, pp. 119, 1221 Google Scholar.

7 Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XIV, No. 347, as cited; The New York Times, Feb. 12, 1946.

8 Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XIV, No. 345 (February 10, 1946), pp. 189–90.

9 Harvard Research in International Law, Law of Treaties, this Journal, Vol. 29 (1935), Supplement, p. 1008.

10 See Myres McDougal, S. and Lans, Asher, “Treaties and Congressional-Executive or Presidential Agreements: Interchangeable Instruments of National Policy,” in 54 Yale Law-Journal (1945), pp. 181–351 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, 534–615, especially 318–351; Edwin M. Borchard, “Treaties and Executive Agreements—A Reply,” in same, pp. 616–664, especially pp. 637 ff., 657 ff.

11 Quoted in Hackworth, Green H., Digest of International Law, Vol. V, p. 403 Google Scholar, from Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, 551–552.

12 See instances cited by McDougal-Lans, pp. 343–345.

13 Law of Treaties, this Journal, Vol. 29 (1935), Supplement, pp. 667, 1008.

14 From a letter from the Chief of the Treaty Division, U. S. Department of State, to William Hays Simpson, Dec. 7, 1934, quoted in William Hays Simpson, “Legal Aspects of Executive Agreements,” in 24 Iowa Law Review (1938), pp. 67, 86.

15 Congressional Record, Vol. 91, Part 2, p. 1620 (March 1, 1945).

16 Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XII, No. 297 (March 4, 1945), p. 324.

17 It is not without interest that the Report on the Crimea Conference released Feb. 12, 1945, although signed by Messrs. Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin, does not purport to be an “agreement,” but is referred to in its text as a “statement” on the results of the conference: Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XII, No. 295 (Feb. 18,1945), pp. 213–6.

- 2

- Cited by