Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

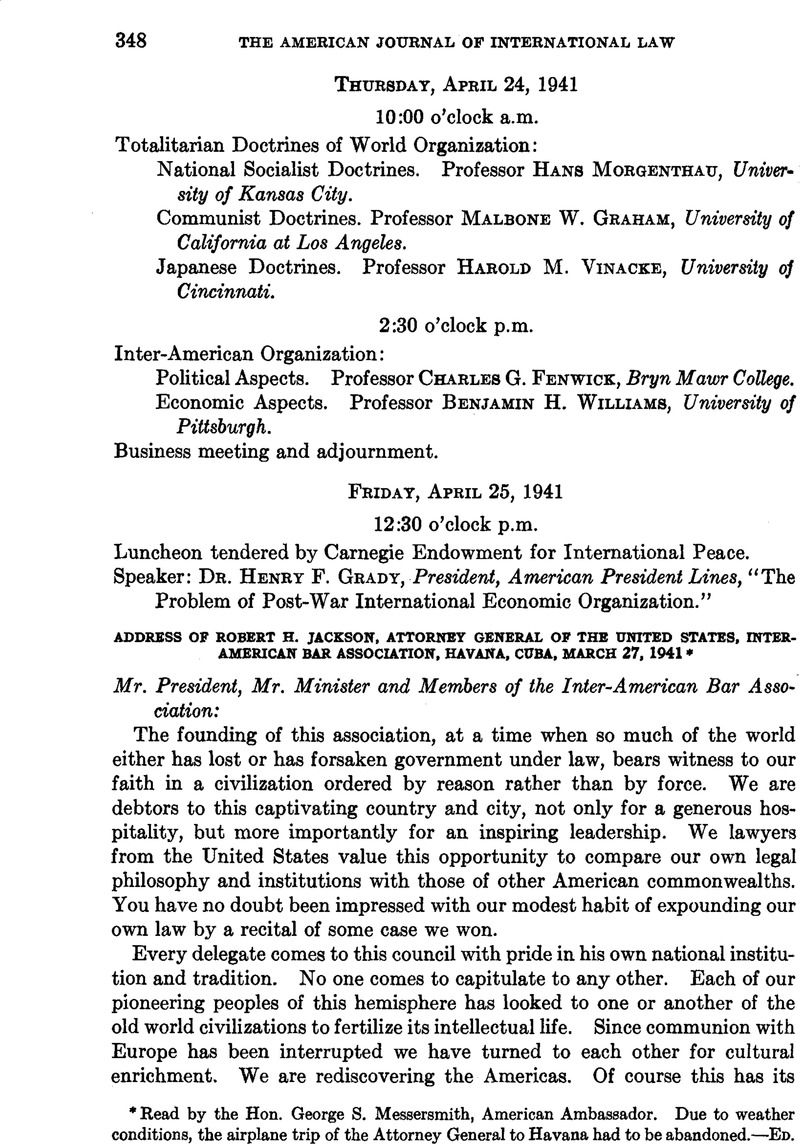

Read by the Hon. George S. Messersmith, American Ambassador. Due to weather conditions, the airplane trip of the Attorney General to Havana had to be abandoned.—E d .

1 Hall’s International Law, 5th ed., 1904, p. 61.

2 3 De Jure Belli oc Pads (Whewell ed., 1853), p. 293.

3 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was not uncommon to grant the right of passage to one belligerent only. In particular, such one-sided aid was freely extended in pursuance of pre-existing treaties promising help in case of war. It comprised not only the right of passage, but also deliveries of supplies and contingents of troops. This admissibility of qualified neutrality, in conformity with previous treaty obligations, was approved by writers of authority, including leading publicists like Vattel and Bynkershoek, who otherwise stressed the duties of impartial conduct. Wheaton, the leading American writer, asserted, as late as 1836, that a neutral may be bound, as the result of a treaty concluded before the war, to furnish one of the belligerents with money, ships, troops, and munitions of war. Kent, another authoritative publicist, expressed a similar view. Distinguished European writers, like Bluntschli, shared the same opinion. Even as late as the nineteenth century, governments occasionally acted on the view that qualified neutrality was admissible. In 1848, in the course of the war between Denmark and Germany, Great Britain, acting in execution of her treaty with Denmark, prohibited the export of munitions to Germany. During the South African War, Portugal complied with the obligations of her treaty with Great Britain and permitted the landing of British troops on Portuguese territory.

4 Root’s letter to House appears in The Intimate Papers of Colonel House, arranged by Charles Seymour, Vol. IV, p. 43. See also Jessup, Elihu Root, Vol. II, p. 376.

5 Almost contemporaneously with going into force of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, and at a time when it was not self-serving, United States Secretary of State Stimson, in 1932, announced his view of the change which that treaty wrought in our legal philosophy: “War between nations was renounced by the signatories of the Briand-Kellogg Treaty. This means that it has become illegal throughout practically the entire world. It is no longer to be the source and subject of rights. It is no longer to be the principle around which the duties, the conduct, and the rights of nations revolve. It is an illegal thing. Hereafter when two nations engage in armed conflict either one or both of them must be wrongdoers — violators of this general treaty law. We no longer draw a circle about them and treat them with the punctilios of the duelist’s code. Instead we denounce them as law-breakers.

“ By that very act we have made obsolete many legal precedents and have given the legal profession the task of reëxamining many of its codes and treatises.” “The Pact of Paris: Three Years of Development,” address by the Honorable Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State, before the Council on Foreign Relations, Aug. 8, 1932, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1932; Foreign Affairs, Supp., Oct. 1932.

These codes and treatises have been and are being reexamined as Secretary Stimson suggested they must be, and the legal consequences of the Kellogg-Briand Pact in the matter of neutrality were formulated in the so-called Budapest Articles of Interpretation adopted in 1934 by the International Law Association. They read as follows:

“Whereas the Pact is a multilateral law-making treaty whereby each of the High Contracting Parties makes binding agreements with each other and all of the other High Contracting Parties, and

“Whereas by their participation in the Pact sixty-three States have abolished the conception of war as a legitimate means of exercising pressure on another State in the pursuit of national policy and have also renounced any recourse to armed force for the solution of international disputes or conflicts:

“ (1) A signatory State cannot, by denunciation or non-observance of the Pact, release itself from its obligations thereunder.

“ (2) A signatory State which threatens to resort to armed force for the solution of an international dispute or conflict is guilty of a violation of the Pact.

“ (3) A signatory State which aids a violating State thereby itself violates the Pact.

“ (4) In the event of a violation of the Pact by a resort to armed force or war by one signatory State against another, the other States may, without thereby committing a breach of the Pact or of any rule of International Law, do all or any of the following things:

(a) Refuse to admit the exercise by the State violating the Pact of belligerent rights, such as visit and search, blockade, etc.;

(b) Decline to observe towards the State violating the Pact the duties prescribed by International Law, apart from the Pact, for a neutral in relation to a belligerent;

(c) Supply the State attacked with financial or material assistance, including munitions of war;

(d) Assist with armed forces the State attacked.

“ (5) The signatory States are not entitled to recognize as acquired de jure any territorial or other advantages acquired de facto by means of a violation of the Pact.

“ (6) A violating State is liable to pay compensation for all damage caused by a violation of the Pact to any signatory State or to its nationals.

“ (7) The Pact does not affect such humanitarian obligations as are contained in general treaties, such as The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the Geneva Conventions of 1864, 1906 and 1929, and the International Convention relating to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, 1929.” (Report of the 38th Conference of the International Law Association, Budapest (1934), pp. 66–68; also, this Journal, Supp., Vol. 33 (1939), pp. 825–826, n. 1.)

These Budapest Articles did not secure unanimous approval on the part of international lawyers, but they gained support from the majority of them. Even those jurists who felt unable to subscribe fully to the Budapest Articles of Interpretation were emphatic that the Kellogg-Briand Pact effected a decisive change in the position of the law of neutrality. Thus, the late Ake Hammarskjöld, a Judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice from 1936 until his death in 1937, in discussing, in the course of the Budapest Conference, the implications of the Kellogg-Briand Pact in relation to neutrality, said: “You will have noticed that, except when the texts compelled me to use the word ‘neutrality,’ I have been careful to use another word: the status of non-belligerency. . . . I have chosen the other expression merely because I wanted to underline that the status of non-belligerency under the Kellogg Pact is not necessarily identical with the status of neutrality in pre-war international law.” (Report, 38th Conf., loc. cit., p. 31.)

The Budapest Articles of Interpretation were not disapproved by the United States. On the contrary, Secretary of State Stimson, speaking before the American Society of International Law on April 26,1935, said: “Our own government as a signatory of the Kellogg Pact is a party to a treaty which may give us rights and impose on us obligations in respect to the same contest which is being waged by these other nations. The nation which they consider an aggressor and whose actions they are seeking to limit and terminate, may be by virtue of those same actions a violator of obligations to us under the Kellogg Pact. Manifestly this in itself involves to some extent a modification in the assertion of the traditional rights of neutrality. . . .

“Even in the face of this situation some of our American lawyers have insisted that there could be no change in the duty of neutrality imposed by international law. I shall not argue this. To such gentlemen I only commend a study of the recent proceedings last summer of the International Law Association at Budapest. The able group of lawyers from many countries there assembled considered this question and decided that in such a situation the rules of neutrality would no longer apply among the signatories of the Kellogg Pact, and that we, for example, in such a case as I have just supposed, would be under no legal obligation to follow them.” (Proceedings of the American Society of International Law, 1935, pp. 121, 127.)

6 On the initiation of Uruguay, the American states released a joint declaration protesting against the military attacks directed against these states. They declared, in part, that: “The American Republics in accord with the principles of international law and in application of the resolutions adopted in their inter-American conferences, consider unjustifiable the ruthless violation by Germany of the neutrality and sovereignty of Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg.” (Department of State Bulletin, May 25, 1940, p. 568.)